Balls for breakfast!

Fish balls before frying

“For breakfast, the baked beans again – warmed over, of course – and fish balls. I don’t remember ever having fish balls on Saturday, but we never failed to have them Sunday morning. Sometimes rye-meal muffins instead of the brown bread, but beans and fish balls, always. A solid orthodox breakfast like that laid the foundation for the orthodox day that followed.”

— Joseph C. Lincoln in Cape Cod Yesterdays (1935)

A fishball was a fried New England concoction made of potatoes and fish stock, and usually eaten for breakfast.

But they took only cash

The Red Coach Grill was a very popular New England restaurant chain in the ‘60s. Look at the prices!

Todd McLeish: She's watching deer, earthworms and other threats to region's native plants

A Salt Marsh Pink flower. Hope Lesson is trying to propagate the rare native plant in Connecticut.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Thanks to lessons taught by her grandparents, Hope Leeson has always been drawn to plants. Some of her oldest memories are of trees, especially their different shapes.

“I’ve always had this haunting sense of awareness of their forms,” said Leeson, a botanist, plant conservationist and botanical educator from South Kingstown, R.I., who has walked much of Rhode Island in search of wetlands and rare plants. “I was always interested by their shapes, and by other little things on the ground that also attracted my attention, like the incredible structure of inch-high plants, sedges and flowers. There are so many different unbelievable shapes and forms that plants take.”

Through more than 30 years of field experience, Leeson has developed an intimate knowledge of the Ocean State’s plant communities, and she has applied that knowledge to the protection of rare species, the sustainable collection of plant seeds and the propagation of native plants for habitat-restoration efforts. This work has given her unique insights into the changes taking place in the state’s natural areas and their impacts on native species.

“There’s a lot happening in the ground that we don’t see,” she said. “And there’s certainly a lot happening because of deer eating much of what’s on the ground. Both of those are influencing the next generation of plant communities.”

She noted that Rhode Island’s abundant deer primarily eat native plants, and they are so voracious that in many places few young plants have a chance to mature before they are eaten. And since deer avoid most invasive species, they are providing inroads for invasives to gain a foothold and spread widely.

“I also worry that we’re not really aware of the far-reaching impact of earthworms,” Leeson said of the eight species found in southern New England, all of which originated in Europe or Asia. “The plant communities we have are adapted to a slow cycling of nutrients, and earthworms really speed that up. They also take a lot of leaf litter and pull it down into the soil, which changes the whole nutrient cycle, in terms of what’s available to plants.

“So like deer, earthworms are opening up areas for nonnative species to come in, because those nonnatives come from areas that have earthworms and can take advantage of the opening that’s been created. We can’t control where earthworms go, and they’re really changing the chemistry of the soil.”

It’s not just soil chemistry that’s changing, Leeson said, but it’s also soil temperature. And that may be affecting the mycorrhizal relationship between plants and fungi that enables plants to acquire nutrients through their roots. If that relationship is disrupted, many plant communities could be impacted.

“I just see so many places where it appears like the forest is dying, particularly areas that are more urban,” she said. “It smells different, it looks different, it’s a big change, and how that comes out in the end, we don’t know. It may all be fine, but on our human scale it seems like a loss of something — or maybe there will be a gain in another hundred years.”

Leeson grew up in Providence and South Kingstown and earned an art degree at Brown University, where she took as many environmental courses as she could. After graduating, she spent a few years painting murals in people’s homes and creating decorative stenciling, before taking jobs as a naturalist on Prudence Island and at Goddard Memorial State Park in Warwick. That work led to jobs at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and several environmental consulting firms.

During one project, when the Narragansett Electric Co. proposed a new power line corridor from East Greenwich to Burrillville, R.I., she walked the entire 44 miles to locate any wetlands the route would cross.

In more recent years, she consulted with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Save The Bay, The Nature Conservancy and other agencies to document rare plant communities and invasive species. She also worked for more than 10 years as the botanist for the Rhode Island Natural History Survey.

“Not only does Hope like to dig into the academic understanding of plants, she values the study of native plants because they connect to so many of her other interests and areas of accomplishment, including gastronomy, environmental conservation, art, gardening, teaching, and social networking,” said David Gregg, director of the Natural History Survey. “Her multi-level connection to native plants is readily apparent when you spend time with her, and is an important reason, besides the interest inherent in the projects themselves, that volunteers have been so attracted to working with her on the Survey’s various Rhody Native activities.”

Leeson’s establishment of the Rhody Native program to propagate up to 100 species of native plants helped diversify habitats at wildlife refuges, salt marshes, and private and public gardens. Eventually, the program became so successful that she was receiving orders for thousands of plants, which was more than she could produce on her own. Without a commercial nursery willing to take it over, the program was discontinued.

SShe is now completing a project to grow a rare wildflower called Salt-Marsh Pink, which is limited to two sites in Rhode Island and one in Connecticut. The plants she is growing will be used to bolster the Connecticut population following a restoration of the marsh.

“We thought we might cross-pollinate plants from Connecticut with the Rhode Island populations to reduce the genetic bottleneck,” Leeson said. “But the Rhode Island populations are really small, and rabbits ate all of the seedpods before they were ripe, so I was unable to collect any seedpods. But the Connecticut seeds are sown, and they’re just resting for the winter.”

When she’s not working, Leeson enjoys riding horses, which she said can “eat up a couple hours every other day.” But she’s never far from plants, whether in her garden or in nearby forests.

“I’m drawn to places that are rocky, because that geography and geology is interesting to me,” she said. “And the coastal plain pond shores are endlessly fascinating to me because their geological life cycle is so interesting. When water levels are down, they have this explosion of plant species, many of them rare, and then there will be a decade when everything is underwater and you wait for 10 years before they all reveal themselves again.”

Leeson also enjoys foraging for food, including the tubers of evening primrose, which she roasts with carrots. She even occasionally cooks with invasive species — she makes pie from Japanese knotweed, pesto from garlic mustard, and enjoys the berries from autumn olive.

As she approaches retirement age, Leeson is teaching botany and plant ecology at the Rhode Island School of Design. She is especially looking forward to teaching a five-week course in January called “Winter Treewatching” and a spring semester class on the “Weeds of Providence.”

“That one will look at all of the areas around Providence that are vegetated by things that come in on their own,” Leeson said. “It’s getting people to think about how we don’t even notice these things, and yet they’re performing pretty important functions, from carbon sequestration and air filtration to providing food for insects and birds.”

Although she said that teaching online during the pandemic has been “weird,” she has been pleased to see so many people walking at Rhode Island’s parks and nature preserves.

“It’s really helping people to slow down and look around them more, at least I hope it is,” she said. “They seem to be noticing things they never noticed before, and I think that’s a really good thing.

“We’ve gotten so distanced from the natural world around us that there’s not an impetus to steward it or take care of it. There’s a sense that it will always be there and it doesn’t really matter, but it’s what sustains us all. We won’t exist without it.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

David Warsh: The mysterious machinery of epidemic models

“The Plague of Athens ‘‘ by Michiel Sweerts (painted in 1652-54), illustrating the devastating epidemic that struck Athens in 430 B.C., as described by the historian Thucydides.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is not difficult to identify a 9/11 moment in the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, an event after which everything changed. Until mid-March, politicians in Britain and the United States were cautiously optimistic. Prime Minister Boris Johnson advised, “We should all basically just go about our normal daily lives.” President Trump, in an Oval Office address on March 11, said that for the vast majority of Americans, the risk is very, very low.”

Five days later, on March 16, the British government took the first of a series of measures leading to a lockdown on March 23. On March 17, President Trump read a statement to a press briefing:

My administration is recommending that all Americans, including the young and healthy, work to engage in schooling from home when possible. Avoid gathering in groups of more than 10 people. Avoid discretionary travel. And avoid eating and drinking at bars, restaurants and public food courts. If everyone makes this change or these critical changes and sacrifices now, we will rally together as one nation and we will defeat the virus. And we’re going to have a big celebration all together. With several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly.

What happened? Imperial College, London, released a model-based study on March 16 that made headlines around the world, predicting as many as 2.2 million deaths might occur in the U.S., and 510,000 in the U.K. as a result of the pandemic. To this point, 265,000 US deaths have been reported, and another 58,030 in Britain.

Since March, economists have gone to work seeking to better understand the machinery of epidemiological models and the theories on which they are based. In “An Economist’s Guide to Epidemiology Models of Infectious Disease,” in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, Fall 2020, Christopher Avery, William Bossert, Adam Clark, Glenn Ellison and Sarah Fisher Ellison lay out the facts above, along with some of their findings.

Epidemiology has become more empirical over time, they say, and epidemiologists are learning to add parameters to their models. But they make less of a distinction between theory and empirical approaches than do economists. Meanwhile, “a model which posits a symmetric, bell-shaped evolution of cases over time cannot accommodate repeated changes in the rate of spread due to changing regulations, changing public perception, and ‘quarantine fatigue.’”

Not surprisingly, economists have begun looking for means of suppressing the virus by changing behaviors in manners as cost-effective as possible. Representative is James Stock, of Harvard University, who argued in September that lockdowns are too are too blunt a method to rely on in most cases. In “Policies for a Second Wave,” for a special summer edition of Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Stock and David Baqaee, Emmanuel Farhi and Michael Mina proposed framing the wearing of masks as a patriotic duty, pursuing cheap and rapid testing, stressing contact tracing and quarantine, and implementing waste-water testing as a means of surveillance once the virus is suppressed.

Epidemiology is not the only discipline to come under economists’ lens. Bruce Sacerdote, Ranjan Schgal and Molly Cook ask Why Is All Covid-19 News Bad News? in a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper out this month. They fault mainstream media for underplaying news of vaccine trials and school re-openings. Ninety-one percent of articles by U.S. major media outlets have been negative in tone since the first of the year compared with 54 percent abroad and 65 percent in scientific journals. Stories discussing Donald Trump and hydroxychloroquine were more numerous than all stories combined about companies and individuals working on a vaccine, they complained.

Of course those stories about hydroxychloroquine may have been more about the nature of the president’s leadership than about COVID-19. Even so, there is indeed evidence of hierarchy and momentum in the reporting: what Wall Street Journal columnist Holman Jenkins, Jr. goes on about. It’s going to be a long time before the strange coincidence of Donald Trump and the virus is untangled. Integrated assessment of the pandemic has far to go.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.

Rachana Pradhan: How big pharma money colors Operation Warp Speed

April 16 was a big day for Moderna, the Cambridge, Mass., Massachusetts biotech company on the verge of becoming a front-runner in the U.S. government’s race for a coronavirus vaccine. It had received roughly half a billion dollars in federal funding to develop a COVID shot that might be used on millions of Americans.

Thirteen days after the massive infusion of federal cash — which triggered a jump in the company’s stock price — Moncef Slaoui, a Moderna board member and longtime drug-industry executive, was awarded options to buy 18,270 shares in the company, according to Securities and Exchange Commission filings. The award added to 137,168 options he’d accumulated since 2018, the filings show.

It wouldn’t be long before President Trump announced Slaoui as the top scientific adviser for the government’s $12 billion Operation Warp Speed program to rush COVID vaccines to market. In his Rose Garden speech on May 15, Trump lauded Slaoui as “one of the most respected men in the world” on vaccines.

The Trump administration relied on an unusual maneuver that allowed executives to keep investments in drug companies that would benefit from the government’s pandemic efforts: They were brought on as contractors, doing an end run around federal conflict-of-interest regulations in place for employees. That has led to huge potential payouts — some already realized, according to a KHN analysis of SEC filings and other government documents.

Slaoui owned 137,168 Moderna stock options worth roughly $7 million on May 14, one day before Trump announced his senior role to help shepherd COVID vaccines. The day of his appointment, May 15, he resigned from Moderna’s board. Three days later, on May 18, following the company’s announcement of positive results from early-stage clinical trials, the options’ value shot up to $9.1 million, the analysis found. The Department of Health and Human Services said that Slaoui sold his holdings May 20, when they would have been worth about $8 million, and will donate certain profits to cancer research. Separately, Slaoui held nearly 500,000 shares in GlaxoSmithKline, where he worked for three decades, upon retiring in 2017, according to corporate filings.

Carlo de Notaristefani, an Operation Warp Speed adviser and former senior executive at Teva Pharmaceuticals, owned 665,799 shares of the drug company’s stock as of March 10. While Teva is not a recipient of Warp Speed funding, Trump promoted its antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine as a COVID treatment, even with scant evidence that it worked. The company donated millions of tablets to U.S. hospitals and the drug received emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration in March. In the following weeks, its share price nearly doubled.

Two other Operation Warp Speed advisers working on therapeutics, Drs. William Erhardt and Rachel Harrigan, own financial stakes of unknown value in Pfizer, which in July announced a $1.95 billion contract with HHS for 100 million doses of its vaccine. Erhardt and Harrigan were previously Pfizer employees.

“With those kinds of conflicts of interest, we don’t know if these vaccines are being developed based on merit,” said Craig Holman, a lobbyist for Public Citizen, a liberal consumer advocacy group.

An HHS spokesperson said the advisers are in compliance with the relevant federal ethical standards for contractors.

These investments in the pharmaceutical industry are emblematic of a broader trend in which a small group with the specialized expertise needed to inform an effective government response to the pandemic have financial stakes in companies that stand to benefit from the government response.

Slaoui maintained he was not in discussions with the federal government about a role when his latest batch of Moderna stock options was awarded, telling KHN he met with HHS Secretary Alex Azar and was offered the position for the first time May 6. The stock options awarded in late April were canceled as a result of his departure from the Moderna board in May, he said. According to the KHN analysis of his holdings, the options would have been worth more than $330,000 on May 14.

HHS declined to confirm that timeline.

The fate of Operation Warp Speed after President-elect Biden takes office is an open question. While Democrats in Congress have pursued investigations into Warp Speed advisers and the contracting process under which they were hired, Biden hasn’t publicly spoken about the program or its senior leaders. Spokespeople for the transition didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The four HHS advisers were brought on through a National Institutes of Health contract with consulting firm Advanced Decision Vectors, so far worth $1.4 million, to provide expertise on the development and production of vaccines, therapies and other COVID products, according to the federal government’s contracts database.

Slaoui’s appointment in particular has rankled Democrats and organizations such as Public Citizen. They say he has too much authority to be classified as a consultant. “It is inevitable that the position he is put in as co-chair of Operation Warp Speed makes him a government employee,” Holman said.

The incoming administration may have a window to change the terms under which Slaoui was hired before his contract ends, in March. Yet making big changes to Operation Warp Speed could disrupt one of the largest vaccination efforts in history while the American public anxiously awaits deliverance from the pandemic, which is breaking daily records for new infections. Warp Speed has set out to buy and distribute 300 million doses of a COVID vaccine, the first ones by year’s end.

“By the end of December we expect to have about 40 million doses of these two vaccines available for distribution,” Azar said Nov. 18, referring to front-runner vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna.

Azar maintained that Warp Speed would continue seamlessly even with a “change in leadership.” “In the event of a transition, there’s really just total continuity that would occur,” the secretary said.

Pfizer, which didn’t receive federal funds for research but secured the multibillion-dollar contract under Warp Speed, on Nov. 20 sought emergency authorization from the FDA; Moderna just announced that it would do so. In total, Moderna received nearly $1 billion in federal funds for development and a $1.5 billion contract with HHS for 100 million doses.

While it’s impossible to peg the precise value of Slaoui’s Moderna holdings without records of the sale transactions, KHN estimated their worth by evaluating the company’s share prices on the dates he received the options and the stock’s price on several key dates — including May 14, the day before his Warp Speed position was announced, and May 20.

However, the timing of Slaoui’s divestment of his Moderna shares — five days after he resigned from the company’s board — meant that he did not have to file disclosures with the SEC confirming the sale, even though he was privy to insider information when he received the stock options, experts in securities law said. That weakness in securities law, according to good-governance experts, deprives the public of an independent source of information about the sale of Slaoui’s stake in the company.

“You would think there would be kind of a one-year continuing obligation [to disclose the sale] or something like that,” said Douglas Chia, president of Soundboard Governance and an expert on corporate governance issues. “But there’s not.”

HHS declined to provide documentation confirming that Slaoui sold his Moderna holdings. His investments in London-based GlaxoSmithKline — which is developing a vaccine with French drugmaker Sanofi and received $2.1 billion from the U.S. government — will be used for his retirement, Slaoui has said.

“I have always held myself to the highest ethical standards, and that has not changed upon my assumption of this role,” Slaoui said in a statement released by HHS. “HHS career ethics officers have determined my contractor status, divestures and resignations have put me in compliance with the department’s robust ethical standards.”

Moderna, in an earlier statement to CNBC, said Slaoui divested “all of his equity interest in Moderna so that there is no conflict of interest” in his new role. However, the conflict-of-interest standards for Slaoui and other Warp Speed advisers are less stringent than those for federal employees, who are required to give up investments that would pose a conflict of interest. For instance, if Slaoui had been brought on as an employee, his stake from a long career at GlaxoSmithKline would be targeted for divestment.

Instead, Slaoui has committed to donating certain GlaxoSmithKline financial gains to the National Institutes of Health.

Offering Warp Speed advisers contracts might have been the most expedient course in a crisis.

“As the universe of potential qualified candidates to advise the federal government’s efforts to produce a COVID-19 vaccine is very small, it is virtually impossible to find experienced and qualified individuals who have no financial interests in corporations that produce vaccines, therapeutics, and other lifesaving goods and services,” Sarah Arbes, HHS’s assistant secretary for legislation and a Trump appointee, wrote in September to Rep. James Clyburn (D.-S.C.), who leads a House oversight panel on the coronavirus response.

That includes multiple drug-industry veterans working as HHS advisers, an academic who’s overseeing the safety of multiple COVID vaccines in clinical trials and sits on the board of Gilead Sciences, and even former government officials who divested stocks while they were federal employees but have since joined drug company boards.

Dr. Scott Gottlieb and Dr. Mark McClellan, former FDA commissioners, have been visible figures informally advising the federal response. Each sits on the board of a COVID vaccine developer.

After leaving the FDA in 2019, Gottlieb joined Pfizer’s board and has bought 4,000 of its shares, at the time worth more than $141,000, according to SEC filings. As of April, he had additional stock units worth nearly $352,000 that will be cashed out should he leave the board, according to corporate filings. As a board member, Gottlieb is required to own a certain number of Pfizer shares.

McClellan has been on Johnson & Johnson’s board since 2013 and earned $1.2 million in shares under a deferred-compensation arrangement, corporate filings show.

The two also receive thousands of dollars in cash fees annually as board members. Gottlieb and McClellan frequently disclose their corporate affiliations, but not always. Their Sept. 13 Wall Street Journal op-ed on how the FDA could grant emergency authorization of a vaccine identified their FDA roles and said they were on the boards of companies developing COVID vaccines but failed to name Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. Both companies would benefit financially from such a move by the FDA.

“It isn’t a lower standard for FDA approval,” they wrote in the piece. “It’s a more tailored, flexible standard that helps protect those who need it most while developing the evidence needed to make the public confident about getting a Covid-19 vaccine.”

About the inconsistency, Gottlieb wrote in an email to KHN: “My affiliation to Pfizer is widely, prominently, and specifically disclosed in dozens of articles and television appearances, on my Twitter profile, and in many other places. I mention it routinely when I discuss Covid vaccines and I am proud of my affiliation to the company.”

A spokesperson for the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy, which McClellan founded, noted that other Wall Street Journal op-eds cited his Johnson & Johnson role and that his affiliations are mentioned elsewhere. “Mark has consistently informed the WSJ about his board service with Johnson & Johnson, as well as other organizations,” Patricia Shea Green said.

Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine is in phase 3 clinical trials and could be available in early 2021.

Still, while they worked for the FDA, Gottlieb and McClellan were subject to federal restrictions on investments and protections against conflicts of interest that aren’t in place for Warp Speed advisers.

According to the financial disclosure statements they signed with HHS, the advisers are required to donate certain stock profits to the NIH — but can do so after the stockholder dies. They can keep investments in drug companies, and the restrictions don’t apply to stock options, which give executives the right to buy company shares in the future.

“This is a poorly drafted agreement,” said Jacob Frenkel, an attorney at Dickinson Wright and former SEC lawyer, referring to the conflict-of-interest statement included in the NIH contract with Advanced Decision Vectors, the Warp Speed advisers’ employing consulting firm. He said documents could have been “tighter and clearer in many respects,” including prohibiting the advisers from exercising their options to buy shares while they are contractors.

De Notaristefani stepped down as Teva’s executive vice president for global operations in October 2019, but according to corporate filings he would remain with the company until the end of June 2020 in order to “ensure an orderly transition.” He’s been working with Warp Speed since at least May overseeing manufacturing, according to an HHS spokesperson.

When Erhardt left Pfizer in May, U.S. COVID infections were climbing and the company was beginning vaccine clinical trials. Erhardt and Harrigan, whose LinkedIn profile says she left Pfizer in 2010, have worked as drug industry consultants.

“Ultimately, conflicts of interest in ethics turn on the mindset behavior of the responsible persons,” said Frenkel, the former SEC attorney. “The public wants to know that it can rely on the effectiveness of the therapeutic or diagnostic product without wondering if a recommendation or decision was motivated for even the slightest reason other than product effectiveness and public interest.”

Rachana Pradhan is a Kaiser Health News correspondent.

Looking across the Charles River toward Kendall Square, Cambridge, headquarters of Moderna and other tech companies.

'Black parabolas'

“When the mink ran across the meadow in bunched

black parabolas, I thought

sine and cosine, but no —

the movement never dips

below the line.’’

— From “The Mink,’’ by Rosanna Warren (born in 1953 in Fairfield, Conn.), the daughter of the late novelist, literary critic and U.S. poet laureate Robert Penn Warren and writer Eleanor Clark. She graduated from Yale University with a degree in painting.

Mink have staged a comeback in New England in recent decades.

Route 1, aka the Boston Post Road, in downtown Fairfield in 1953, when Ms. Warren was three. Route i was the main drag or the Northeast back then, before the Interstate Highway System.

.

Fidelity seeks to hire 500 new employees in N.H.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Fidelity Investments has announced plans to hire 500 new employees for its Merrimack campus. The hiring is part of a company-wide initiative to add 4,000 new employees across the country.

“Fidelity has experienced a 24 percent increase in planning engagement activity as new investors open accounts, driving the need for more personnel at the company. Fidelity also plans to accept 1,000 college and university students into its 2021 internship program, as well as 500 graduates to participate in post-grad job training opportunities. Fidelity currently employs 5,300 in New Hampshire.

“‘We’re looking for financial advisers, licensed representatives, software engineers and customer service representatives to fill thousands of roles across the country over the next six months,’ said Kathleen Murphy, president of personal investing at Fidelity.’’

Read more from the New Hampshire Union Leader.

xxx

English colonists starting settling in Merrimack, named for a Native-American term for sturgeon, a once-plentiful fish in the area’s rivers, in the late 17th Century. For decades, the land was in dispute between the Province of New Hampshire and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. (Of course, both had seized the land from the Indians.)

The town had many farms into the 20th Century but has since become a place, with office parks, including for big corporations, and a bedroom community for commuters to Greater Boston and cities in southeastern New Hampshire.

The Souhegan River in Merrimack, also the name of the region’s biggest river.

The First Church of Christ in Merrimack.

Clamming in a golden place

Going clamming via the marshes of Barnstable,Mass.

— Photo by Elizabeth Whitcomb

— Elizabeth Whitcomb

— Photo by Justin Kaneps

That's that

“Fall Fell” (Sandwich, Mass.) (aluminarte print), by Bobby Baker. Copyright Bobby Baker Fine Art.

See:

https://bobbybaker.gallery/

Tough look at 1950s America

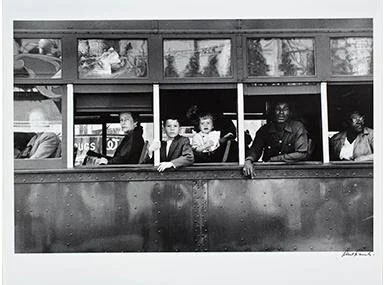

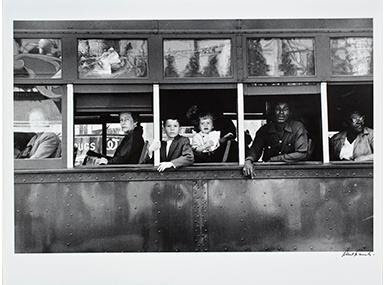

“Trolley—New Orleans ‘‘ (neg. 1955-1956, print 1989, gelatin silver print) , by the great Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank (1924-2019) as seen in his book The Americans.

A show — “Robert Frank: The Americans” — running until April 11 at the Addison Gallery of American Art, at Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., displays a range of photographs from the famed book, providing an unflinching account of 1950s America. Note in this picture that the Blacks had to sit in the back in the still-segregated South.

The unusual Andover Town Hall.

A silvery lure

“An old silvery shed puzzles me with longing

And I free myself

By carefully slipping the reins from my shoulders

To follow:

But where? How can I move and keep the shed in view?’’

--From “The Shed,’’ by Henry Braun (1930-2014). After teaching literature and creative writing at Temple University, in Philadelphia, he retired to Weld, Maine, in interior western Maine, near the White Mountains, where he lived off the grid, as if in response to years of gritty city life.

Mt. Blue and Webb Lake, in Weld, Maine.

'Vast aspiration of man'

The spectacular main, Renaissance Revival facility of the Boston Public Library, on Copley Square, Boston. Designed by the famed architect Charles McKim, the building was opened in 1895. It faces another masterpiece: Henry Hobson Richardson’s Romanesque Trinity Church (see photo below), which was opened in 1877. The two help make Copley Square one of America’s most beautiful public places.

“For no matter how they might want to ignore it, there was an excellence about this city {Boston}, an air of reason, a feeling for beauty, a memory of something very good, and perhaps a reminiscence of the vast aspiration of man which could never entirely vanish.’’

— Arona McHugh (1924-1996), author of two novels set in Boston — The Seacoast of Bohemia and A Banner with a Strange Device.

Philip K. Howard: Principles to unify America

The Great Seal of the United States. The Latin means “Out of Many, One’’

“America is deeply divided”: That’s the post-mortem wisdom from this year’s election.

Surveys repeatedly show, however, that most Americans share the same core values and goals, such as responsibility, accountability and fairness. One issue that enjoys overwhelming popular support is the need to fix broken government. Two-thirds of Americans in a 2019 University of Chicago/AP poll agreed that government requires “major structural changes.”

President-elect Biden has a unique opportunity to bring Americans together by focusing on making government work better. Extremism is an understandable response to the almost perfect record of public failures in recent years. The botched response to COVID-19, and continued confusion over imposing a mask mandate, are just the latest symptoms of a bureaucratic megalith that can’t get out of its own way. Almost a third of the health-care dollar goes to red tape. The United States is 55th in World Bank rankings for ease of starting a business. The human toll of all this red tape is reflected in the epidemic of burnout in hospitals, schools, and government itself.

More than anything, Washington needs a spring cleaning. Officials and citizens must have room to ask: “What’s the right thing to do here?” If we want schools and hospitals to work, and for permits to be given in months instead of years, Americans at every level of responsibility must be liberated to use their common sense. Accountability, not suffocating legal dictates, should be our protection against bad choices.

But there’s a reason why neither party presented a reform vision: It can’t be done without cleaning out codes that are clogged with interest-group favors. Changing how government works is literally inconceivable to most political insiders. I remember the knowing smile of then-House Speaker John Boehner’s (R.-Ohio) when I suggested a special commission to clean out obsolete laws, such as the 1920 Jones Act, which, by forbidding foreign-flag ships from transporting goods between domestic ports, can double the cost of shipping. I also remember the matter-of-fact rejection by then-Rep. Rahm Emanuel (D.-Ill.) of pilot projects for expert health courts — supported by every legitimate health-care constituency, including AARP and patient groups — when he heard that the National Trial Lawyers opposed it: “But that’s where we get our funding.”

Cleaning the stables would help everyone, but the politics of incremental reform are insurmountable. That’s why, as with closing unnecessary defense bases, the only path to success is to appoint independent commissions to propose simplified structures. Then interest groups and the public at large can evaluate the overall benefits of the new frameworks.

Over the summer, 100 leading experts and citizens, including former governors and senators from both parties, launched a Campaign for Common Good calling for spring cleaning commissions. Instead of thousand-page rulebooks, the Campaign proposed that new codes abide by core governing principles, more like the Constitution, that honor the freedom of citizens and officials alike to use their common sense:

Six Principles to Make Government Work Again

Govern for Goals. Government must focus on results, not red tape. Simplify most law into legal principles that give officials and citizens the duty of meeting goals, and the flexibility to allow them to use their common sense.

Honor Human Responsibility. Nothing works unless a person makes it work. Bureaucracy fails because it suffocates human initiative with central dictates. Give us back the freedom to make a difference.

Everyone is Accountable. Accountability is the currency of a free society. Officials must be accountable for results. Unless there’s accountability all around, everyone will soon find themselves tangled in red tape.

Reboot Regulation. Too few government programs work as intended. Many are obsolete. Most squander public and private resources with bureaucratic micromanagement. Rebooting old programs will release vast resources for current needs such as the pandemic, infrastructure, climate change, and income stagnation.

Return Government to the People. Responsibility works for communities as well as individuals. Give localities and local organizations more ownership and control of social services, including, especially, for schools and issues such as homelessness.

Restore the Moral Basis of Public Choices. Public trust is essential to a healthy culture. This requires officials to adhere to basic moral values — especially truthfulness, the golden rule, and stewardship for the future. All laws, programs and rights mist be justified for the common good. No one should have rights superior to anyone else.

Is America divided? Many of the problems that caused people to take to the streets this year reflect the inability of officials to act on these principles. The cop involved in the killing of George Floyd should have been taken off the streets years ago — but union rules made accountability impossible. The delay in responding to COVID was caused in part by ridiculous red tape. The inability to build fire breaks on the west coast was caused by procedures that disempowered forestry officials.

The enemy is not each other, as President-elect Biden has repeatedly said. The enemy is the Washington status quo — a ruinously expensive and paralytic bureaucratic quicksand. Change is in the air. But the politics are impossible. That’s why one of first acts of President Biden should be to appoint spring cleaning commissions to propose new frameworks that will liberate Americans at all levels of responsibility to roll up their sleeves and make America work again.

American government needs big change, but the changes could hardly be less revolutionary. Instead of attacking each other, Americans need to unite around core values of responsibility and good sense.

Philip K. Howard is founder of Campaign for Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense. Follow him on Twitter: @PhilipKHoward.

Mr. Howard, a lawyer, is the founder and chairman of the nonprofit legal- and regulatory-reform organization Common Good (commongood.org), a New York City-based civic and cultural leader and a photographer. This piece first ran in The Hill.

What goes up....

“On The Rise” (oil), by Judith Brassard Brown, in her show “On the Rise and Fall,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Dec. 90- Jan. 17. She teaches at the Montserrat College of Art, in Beverly, Mass.

See:

http://www.judithbrassardbrown.com/

and:

www.kingstongallery.com

'Winter is summer'

Headquarters of The Providence Journal, which is controlled by cost-slashing private-equity investors.

“There are ways to get rich: Find an old corporation,

self-insured, with capital reserves. Borrow

to buy: Then dehire managers; yellow-slip maintenance;

pay public relations to explain how winter is summer….’’

-- From “The One Day,’’ by New Hampshire poet Donald Hall (1928-2018)

'Silly waste of time'

Skiers practicing the “Christiania turn” (aka stem christie).

“By 1920, we had begun to use skis fairly consistently instead of snowshoes at Tolman Pond {in Nelson, N.H.}. A Norwegian family who visited at the farm introduced us to bindings that stayed put reasonably well, and to ski wax and proper poles, and soon we were exploring the magical mysteries of the Christiania turn…. But it was all strictly for fun and nobody dreamed a business might be made out of it. In fact the older generation did its best to discourage us from such a dangerous and silly waste of time.’’

-- Newton F. Tolman, in North of Monadnock (1957)

The Nelson Community Church, with the town’s famous mailbox shelter in front.

Nelson, founded in 1774, was originally named Packersfield, after a founder, Thomas Packer, the sheriff at Portsmouth. But the name was changed in 1814 to honor Viscount Horatio Nelson, British admiral and naval hero. This may seem strange, especially considering that the War of 12812 was underway. But many New Englanders opposed the war and Southern domination of the U.S. government and would have willingly accept a return to British rule.

Nelson, with four streams to provide power, developed into a prosperous small manufacturing town in the 19th Century, making cotton cloth and wooden chairs. That’s long gone and Nelson for many years has been a summer and weekend place. It has long lured writers, such as poet and memoirist May Sarton, and professional and amateur painters.

Sawmill in Nelson, 1914

William Morgan: Looking lithographically at proud 19th Century Maine

As part of its celebration of the 200th anniversary of Maine statehood, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art last winter held an exhibition of lithographs of 19th-Century town views in the Pine Tree State. Since then, the college and Brandeis University Press have published a handsome oversize book, Maine's Lithographic Landscapes: Town and City Views, 1830-1870.

What it says above:

“View of Portland, Me./Taken from Cape Elizabeth before the great conflagration of July 4th 1866

“Tinted lithograph from a photograph taken by Edward F. Smith and published by B.B. Russell & Co., Boston. 1866. ‘‘

The author is Maine State Historian Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., who was the state's historic-preservation officer for nearly five decades. The modest and scholarly Shettleworth may well know more about the state's architecture and other art than anyone else. Devoting his life to documenting everything Maine, he has written and lectured prodigiously on every aspect of Maine's built environment, and also written studies of female fly fisherman, photographers, painters, and parks.

“Augusta, Me., 1854.

Drawn by Franklin B. Ladd. Tinted lithograph by F. Heppenheimer, New York.’’

In a bit of Maine understatement, the co-director of the Bowdoin Museum, Frank H. Goodyear Jr., writes, "In Nineteenth Century America, the printed city view enjoyed wide popularity." As Shettleworth notes, the prints helped "forge the young state's identity” and served as "expressions of pride of place’’. During the period under review many towns and cities across America were memorialized in printed images drawn by artists famous and unknown.

Still, Maine was still a small state in the back of beyond. (its population was under 300,000 at the time it separated from Massachusetts, in 1820.) Thus, what the book’s creators call the "first comprehensive record of urban prints during the first fifty years of statehood" is somewhat limited: There are a total of 26 views of 11 places. Those are augmented by a score or more images of the often somber Bowdoin campus, including a painting, old photos, and two Wedgwood plates. Groundbreaking as the book is, viewing the exhibition itself would probably be more satisfying.

That said, Maine's Lithographic Landscapes is a handsome production. The Bowdoin Museum has a history of elegant catalogs, and this co-operative venture with Brandeis demonstrates that press's growing role as a publisher of New England studies. I am not sure that anyone looks at colophons (publisher’s emblems) anymore, so it is worth noting that the book was designed by the eminent book designer, Sara Eisenman.

Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Maine's Lithographic Landscapes, Brandeis University Press, 2020, 144 pages, $50.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian, photographer and essayist. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

Seeing red in 2020

“The Red Road” (acrylic on canvas), by Mark Chadbourne, in the show “RED 2020,’’ in the Cambridge (Mass.) Art Association’s Kathryn Schultz Gallery, through Dec. 17. The gallery has an annual show that is always titled BLUE or RED. RED can evoke happiness (your “red letter day”) and passion but it can also summon up intensity, including violence and pain, of which we’ve had plenty this year.