‘We are still here’

The cairn in question.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I wrote too whimsically in an Oct. 23 column that I had come across this cairn while walking on the lawn at the Roger Williams National Memorial, in downtown Providence, and asked what it is. Here’s the answer from the National Park Service, via my friend Ken Williamson, who lives in Hawaii.

“This cairn, or stone pile, depicts pieces of Narragansett {Tribal Nation}

history from pre-contact {with Europeans} through today. Built by Narragansett artists associated with the Tomaquag Museum {in Exeter, R.I.} it expresses the fact that WE ARE STILL HERE. The cairn is at the center with 4 raised stones around it representing the Four Directions. It is a meditative circle, representing Narragansett lives, history, and future which brings us full circle. Sit down and reflect on your own past, present and future and its intersection with the Narragansett people.

“The Narragansett Tribal Nation has lived on these lands since time immemorial. Their ancestors respected all living things and gave thanks to the Creator for the gifts bestowed on them, as do Narragansett people of today. Lynsea Montanari & Robin Spears III, both Narragansett, served as summer arts interns at the memorial for this project. They incorporated their own cultural knowledge with teachings by tribal elders regarding first contact with European settlers, genocide, displacement, assimilative practices, enslavement, continuation of language, ceremony, and other cultural practices. The artists chose to create a cairn as it is a part of the history of all indigenous peoples. There are many historic cairns in the Narragansett landscape.’’

xxx

My strongest memory of Native American cairns comes from driving with my wife in the forests along the northern side of gorgeous Georgian Bay in Ontario. You can’t go far there without seeing a cairn or other stone sculpture on a slope above the road.

Tomaquag Museum, in the Arcadia section of Exeter, R.I.

—Photo by John Phelan

Take that!

“Hamada” (oil on canvas), by L.G. Talbot, in the show “LG Talbot: New Generation Abstraction,’’ at the University of Massachusetts Fine Arts Center, Amherst, Mass.

The exhibit features abstract work that takes on American abstract painting through large and bold paintings that "convey a distillation of lived experience,’’ says the artist whose home is in the western Massachusetts hill town of Conway and whose studio is in Easthampton, Mass.

Talbot’s artist statement says:

“In the new paintings, I work with palette knives to quickly establish images on the canvas. I keep 4-5 large canvases open – working them simultaneously – impatient for the oil to dry. Images organically surface on the picture plane. I layer more paint and create more texture. My colors have also changed. The primary colors of previous work have been usurped by a more nuanced palette replete with earthy tones. I mix the pigment, thin it out with turpentine, and build the painting in layers. This is my evolution: Borders gone, Colors blended. The pandemic is a reminder of the privilege of being alive – my every day in the studio is charged and intoxicating.’’

Historic Bardwell's Ferry Bridge, in Conway.

— Photo by Doug Kerr

View of Mt. Tom from the center of Easthampton

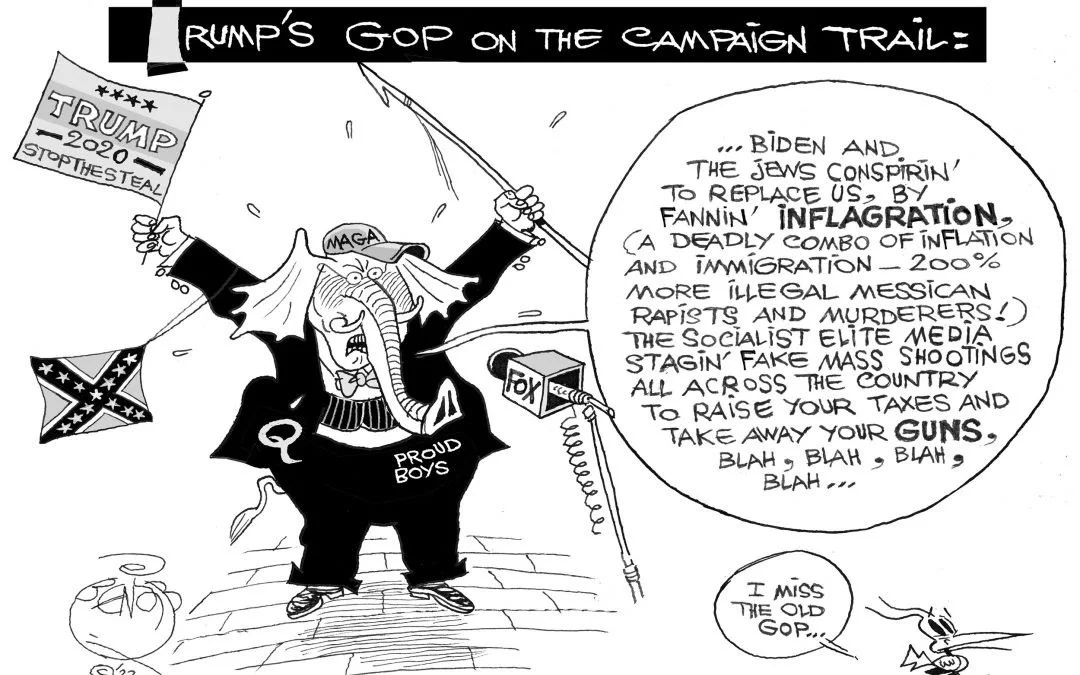

Chris Powell: Rainbow flags are political and so don’t belong in classrooms

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Another front has opened in Connecticut's flag war, this time in Stonington, where, responding to a complaint and acting on legal advice, the school superintendent determined that the "rainbow" or gay pride flags teachers had placed in their classrooms are political and told teachers to remove them.

Whereupon students and others complained that the flags are necessary to show the school system's egalitarianism, and the teachers union asked for a private meeting with the state Board of Education's labor committee to discuss "inclusion." Maybe only a teacher union and a school board would miss the irony of excluding the public from a meeting about "inclusion," but then Connecticut has seen many other indications that some of public education actually despises the public and much prefers to make and implement policy in secret.

After being subjected to this political pressure, the superintendent reversed herself on the rainbow flags, decided that they are not political after all, and withdrew her order to remove them from classrooms.

But of course the rainbow flag is political and propagandistic, lending itself to various uses and interpretations, and so doesn't belong in government settings. If the flag signifies the acceptance and equality of people regardless of sexual orientation, so do the national and Connecticut flags, insofar as federal and state law prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

But the rainbow flag goes farther. To some it also means the right of biologically male students to use women's restrooms and participate in women's sports, thereby nullifying Title IX of federal civil-rights law. To others it means the right of school systems to treat the gender dysphoria of students and even facilitate their gender transition without the knowledge of their parents. The flag is used in various controversial contexts. There is and can be no official interpretation of it.

Municipal governments lately have been discovering that their endorsement is being sought for many flags, and that allowing some to fly on government property but not others raises a First Amendment issue. Some municipalities have decided, wisely, to stay out of the flag wars and confine themselves to government's own flags.

Of course, every school system and government agency should follow the laws against discrimination by sexual orientation. But a rainbow flag is not necessary to establish and publicize such a policy. Schools can act just as employers act at government direction and post notices of the policies required by law. If students of minority sexual orientation are really as timid as claimed by the advocates of putting the rainbow flag in classrooms and can't be comfortable in school without the flag being displayed, notices of non-discrimination policy can be posted in every classroom, even on every student's desk.

But neither such notices nor rainbow flags themselves are any defense against bullying, abuse, and other misconduct. The only defense is strong public administration, and Connecticut's schools are notorious for their lack of standards and discipline for students and employees alike.

Stonington's school administration has just shown itself to be another pushover.

xxx

Campaign commercials are often nasty and sometimes brutal and even deceitful. But Connecticut has seen few as disgraceful as one being aired by Gov. Ned Lamont, a Democrat seeking re-election.

The Lamont commercial depicts a bunch of people making fun of the name of the governor's Republican opponent, Bob Stefanowski. They call him "Stefa-nasty," though the Republican has maintained a softer and more informed tone than when he ran four years ago.

Name calling used to be considered childish and stupid, but apparently no longer at the highest level of state government.

Commercials for the re-election of 5th District Democratic U.S. Rep. Jahana Hayes have been attacking her Republican challenger, former state Sen. George Logan, signifying that the Democrats consider that race unusually competitive. But now commercials for the re-election of Democratic U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal are attacking his Republican opponent, Donald Trump devotee Leora Levy, implying that Democrats think that even Blumenthal, who has been in elective office for 38 years, may be in trouble too. Could it be?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Connecticut. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

Water Street shops and restaurants in Historic (and rich) Stonington

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Existential confusion

Inside Greg’s Famous Seafood, in Fairhaven, Mass.

— Photo by William Morgan

Llewellyn King: Save farmland from solar arrays, for which there are better places

This becomes….

…. this

And this

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

In nearly every city in the United States, and many around the world, bulldozers are busy making dreams come true: Leveling land for a single-family home on a lot.

Who doesn’t want a lovely home with a nice bit of land on some tree-lined street? It is the American Dream manifested in bricks and mortar.

Trouble is dreams can morph into nightmares. A growing nightmare across the nation is the incursion of homes onto farmland – land that will be out of production essentially forever.

All around Washington, D.C., I watched year after year for decades lovely farms in adjacent Maryland and Virginia being turned into suburbs — sometimes 70 and more miles from the city center.

It has been a simple tradeoff: There has been a relentless demand for single-family homes and builders see farms, usually family-owned, as ripe fruit ready for picking. When age is an issue, they almost always sell. Farming is a tough, 365-days-a-year undertaking, and a fat check at the end of a farming career is irresistible.

No villains here, but there are consequences. Mark Twain said, “Buy land, they aren’t making it anymore.” Sadly, Twain didn’t take his own advice and instead invested in the tech world of the day: Among other bad investments, he lost a fortune in a company that was trying to perfect a typesetter.

Farmers are special to me. They are the real renaissance men and women. They know a lot about a lot, from being able to gauge the pH levels of soil on their tongues to how to birth a calf, repair a tractor, or raise a barn.

They also know a thing or two about how the government works and filling out forms. They are regulated but have no guaranteed rate of return. They are as subject to the weather over their own land as floods around the world.

Businesses talk about being rewarded for taking a risk. Farmers take a risk with every seed they plant — and the returns aren’t guaranteed.

But, as Gail Chaddock, host, and producer of No Farms, No Future, a podcast of the American Farmland Trust, said, “You can’t blame the farmers, and you can’t blame the developers. But the land we’ll need for food production in the future is being taken.”

What is happening is the irreversible destruction of millions of acres of prime farmland every year. A reverence for farmland needs to enter the culture, she said.

No longer, however, is it just developers buying up farms. Farmland is now being sought by another kind of developer: renewable energy companies. They are buying it for large solar arrays. They also contract with farmers to install windmills which, while not taking so much land out of agricultural use, cumulatively take a lot.

But it is solar farms that are the real problem. Britain is thinking of legislating to prohibit the use of agricultural land for energy production. Other countries are waking to the realization that a field of shining solar collectors is not the same as a field of waving wheat or even lowly cabbages.

As over time we exported our manufacturing, we also have exported our food production. What was once raised on truck farms around the cities is now raised in neighboring Canada and Mexico, or as far away as Chile and South Africa.

Big roofs like this as well as abandoned-mall parking lots and roadsides are far better places to put solar panels than farmland.

There is no compelling reason to cover huge acreages with solar panels. Roofs, rights of way, and urban parking lots could be pressed into service. Railroad tracks cry out for a solar canopy.

Just because energy or housing is a higher economic use for land today doesn’t mean that it won’t have a higher future value, feeding future generations.

Llewellyn King, a veteran columnist and an international energy and utility consultant, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

White House Chronicle

Connected farm in Windham, Maine. The barn dates from the late 18th Century, and the house was built in three stages during the 19th Century. The unconnected garage was a 20th-Century addition. All doors of the structure are visible in this view from the south side, where winter sun would melt accumulated snow and ice. Following the 20th Century outbreak of Dutch elm disease, only one American elm remains of the line that had provided summer shade along the southern and western sides of the building.

‘Spectral New England’

Rhode Island PBS will air Spectral New England at 1 p.m. on Oct. 29 and 10 p.m. on Oct. 31.

Hit this link for some flavor.

‘Since Eden went wrong’

“It was the dingiest bird

you ever saw, all the color

washed from him, as if

he had been standing in the rain,

friendless and stiff and cold,

since Eden went wrong.''

—From “Robin Redbreast,’’ by Stanley Kunitz (1905-2006), American poet and teacher. A Worcester native, he divided much of time in adult life between Provincetown and New York City.

Must have been his brown coat

“{During the Maine hunting season} there’s a lot of noise, and now and then we hear a bullet slap into the clapboards, and once in a while we have to stop husking corn and go up in the woods and bring out a wounded hunter. Bringing out a wounded hunter wouldn’t be so bad if you didn’t have to listen to his companion explain how he looked like a deer.’’

— John Gould (1908-2003), in Neither Hay nor Grass (1951). He lived in Brunswick, Maine.

1912 postcard. The river is the Androscoggin, which starts in the White Mountains.

‘Light and metaphor’ in New England

“Forest Sunset" (pastel on paper), by Anne Emerson, in her show “Sinking Into Nature,’’ at Creative Connections Gallery, Ashburnham, Mass., starting Nov. 5.

Ms. Emerson says in her Web site:

“I am a New England painter and a writer. The two actions seem to me to feed each other, opening me to see the world simultaneously in light and metaphor. I paint what pleases me and what moves me. My paintings are of people, things and places I love, and most of my paintings have personal historical references. The act of painting is a meditation for me, awakening me to ‘all this joy and beauty,’ in the words of my grandmother's favorite prayer. In a way my painting is also an act of longing. It is an effort to capture the extraordinary feeling of being held in a natural place or emotion, suspended in beauty, power, solitude and light.’’

Ashburnham Town Hall

— Photo by John Phelan

Glittery sale

Bid to be luxurious! Sign on East Side of Providence.

— Photo by Robert Whitcomb

Heating cities by extracting warmth from cold ocean water

Boston skyline from Spectacle Island.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Of course, Putin’s attack on Ukraine and the resulting European energy crisis have accelerated efforts to create economies not based on gas, oil and coal from petrostate dictatorships such as Russia. It reminds me of the stuff that came out of the pressure of World War II – mass use of antibiotics and radar, jet engines, new building materials and, yes, the atomic bomb, which was used to end the war in Asia and the Pacific started by the brutal Japanese Empire – adding a new kind of existential fear.

One of the most interesting examples of this recent reactive innovation is in Helsinki, Finland.

There, a new, carbon-neutral heating system is planned in which a tunnel will be used to pull water from the seabed, where water temperature stays constant. The water would then be processed through heat pumps.

Bloomberg City Lab reports that “{H}eat exchangers will remove about 2.7 degrees (Fahrenheit) of heat from the seawater, which will later be returned to the sea via another nine-kilometer tunnel. The energy collected will then be refined via the heat pump process to reach temperatures of up to 203 degrees.’’

Bloomberg reports that “by processing the water through underground heat pumps, the system could generate enough heat to serve as much as 40 percent of the Finnish capital.’’

This is something that should be looked into by some New England coastal communities, especially the biggest ones — Boston, Providence, New Haven, Portland, New London, etc. Meanwhile, if you can scrounge the several thousand dollars to buy and install a heat pump for your home, you can save a lot of money over the long run.

Ships of state need smiles

The Aldrich House on College Hill in Providence, where Abby Rockefeller spent much of her youth.

“A nation without humor is not only sad but dangerous.’’

— Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (1874-1948), philanthropist, most famously as a patron of modern art, daughter of very powerful U.S. Sen. Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island, wife of John D. Rockefeller Jr. and socialite.

Emotional flowers

“Trumpet Vines” (archival pigment print), in the show“Eat Flowers,’’ by Cig Harvey, at Robert Klein Gallery, Boston, through Dec. 18.

The gallery says:

“In this exhibit, the photography of Cig Harvey focuses almost completely on flowers. Harvey wrote that she ‘[wants her] photos to be sensory,’ and with only a quick glance it is clear that the emotion and presence of each piece is palpable.’’

Viktoria Popovska: For New England higher education, cybersecurity signals news threats and opportunities

— Graphic by Michel Bakni

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

Some of the most common cybersecurity threats are malware, ransomware, phishing and spam. For their victims, including higher education institutions (HEIs), cybercrimes range from inconveniences to data breaches to grand heists like the one that struck Cape Cod Community College (CCCC) four years ago.

In 2018, CCCC, in West Barnstable, experienced a cybersecurity attack resulting in $800,000 stolen from school bank accounts. CCCC was ultimately able to recover more than 80% of the money stolen by the hackers, but impacts of the attack still affect the college.

The cyberattack prompted CCCC, known as the 4Cs, to work with an independent consulting firm to learn best practices related to the institution’s cybersafety. These included, for example, installing endpoint protection software applications that protect servers and PCs from malware campuswide.

President John Cox of Cape Cod Community College spoke about the school’s cyberattack and what he has learned from the situation.

“One of the major takeaways from that is when you are looking at a website or anything electronic and you are being asked to open something up or go to a certain website or scan a QR code, unless you are 99% sure that it’s the real deal, then you shouldn’t hesitate to call the people who sent it to verify it.”

The CCCC attack also prompted the community college to reevaluate its degree programs. In the 2020-21 academic year, CCCC began offering a degree and certification in Information Technology: Cybersecurity. Previously, this pathway had been Information Technology: Security Penetration Testing and though the course requirements haven’t changed much, the new name and reframing of the program is a sign that the 4Cs and other HEIs are realizing the importance of offering cybersecurity programs, and prospective students are taking notice.

Will Markow, the vice president of applied research at LightCast, estimated that his labor market analytics company has seen at least a 40% increase in cybersecurity graduates in the last few years. Despite the rise in people completing cybersecurity degrees, the growth rate of cybersecurity job positions is still double the graduation rate, meaning a cybersecurity skills gap continues to persist.

NEBHE and cybersecurity

NEBHE, with its longtime interest in changing skilled labor demands, has been covering the need for cybersecurity talent for several years. In a 2014 piece in The New England Journal of Higher Education, Yves Salomon-Fernandez, then a vice president at MassBay Community College, wrote about the cybergap and the demand for cybersecurity talent along with New England’s response to the need. Salomon-Fernandez discussed the creation of the New England Cyber Security research consortium, a collaboration between Mass Insight and the Advanced Cyber Security Center. The consortium has evolved into the Cybersecurity Education and Training Consortium, which aims to improve the cybersecurity talent pool. The consortium holds an annual conference where new research is shared and cybersecurity experts lead various workshops.

In 2015, NEBHE announced that cybersecurity was among new academic subject areas to be offered under Tuition Break, NEBHE’s initiative to help students and institutions share high-demand programs. These offerings included associate degree programs in specialized fields such as cybersecurity infrastructure, cybersecurity and healthcare IT, and cybersecurity-digital forensics.

In July 2022, NEBHE, in collaboration with the Business-Higher Education Forum (BHEF), awarded tech talent grants to seven business-higher education partnerships in Connecticut. The grants are a part of an initiative to target growth in tech skills like cybersecurity. Quinnipiac University, the University of Bridgeport and Mitchell college were awarded tech talent grants focused on cybersecurity.

The skills gap

The cybersecurity skills shortage continues to persist and organizations of all types face cybersecurity challenges.

In its 2022 Cybersecurity Skills Gap Global Research Report, Fortinet found that “worldwide, 80% of organizations suffered one or more breaches that they could attribute to a lack of cybersecurity skills and/or awareness.”

The Fortinet report also found that recruiting and retaining cybersecurity talent was a key issue. 60% of organizations have difficulty recruiting cybersecurity professionals and 52% have a difficult time retaining those professionals.

In 2018, The New York Times reported on a prediction from CyberSecurity Ventures that estimated 3.5 million cybersecurity positions will be available but unfulfilled by 2021. CyberSecurity Ventures has since updated its prediction for 2025, but continues to project vacancies at 3.5 million. “Despite industry-wide efforts to reduce the skills gap, the world’s open cybersecurity position in 2021 is enough to fill 50 NFL stadiums,” according to CyberSecurity Ventures.

Clearly, there is a need for more cybersecurity professionals, but why have efforts to reduce the skills gap not worked?

One reason is that people simply aren’t getting the right credentials to secure a cybersecurity position. Many top cybersecurity jobs require not just a bachelor’s degree, but also a master’s and may also require credentials such as a CISSP certification. CISSP stands for Certified Information Systems Security Professional and is independently granted by the International Information System Security Certification Consortium.

Despite the demand for cybersecurity positions to be filled, the industry is slow to soften the credentials or education requirements. But some companies, such as Deloitte, have begun creating a talent pipeline where they train candidates in skills they would not have previously been qualified for.

Cybersecurity and higher education

Cape Cod Community College is far from alone in facing cybersecurity threats.

The threat that cyberattacks pose for HEIs is extremely costly and increasingly frequent, according to April 2022 coverage in Forbes. Ransomware attacks are the most frequent problem for HEIs, with each attack costing on average $112,000 in ransom payments. Forbes writes that HEIs are prime targets for cyberattacks because of their historically underfunded cybersecurity efforts and the way that information sharing and computer systems work in the institutions.

Austin Berglas, global head of professional services and founding member of the cybersecurity firm BlueVoyant, told Forbes that his company had seen a large increase in ransomware attacks in 2020 and 2021 since everyone went remote.

In 2022, a handful of U.S. HEIs have publicly disclosed cyberattacks, according to Hackmageddon, a security breach tracker. Still, most cyberattacks on institutions go unreported unless forced to by law.

Universities have begun upgrading their cyberdefense systems, partially as a result of nudging from the insurance industry.

With the understanding of the threat of cyberattacks, HEIs are working on pumping out cybersecurity professionals.

Consider the University of Bridgeport (Conn.), one of the universities that received a tech talent grant from NEBHE and BHEF. The university announced that it will use the grant money to launch a 12-week course in cybersecurity and information security geared toward the finance and tech sectors. The university plans to offer a certificate to course participants that will allow students to be workforce ready in the cybersecurity field.

Other New England HEIs are also looking to impact the cybersecurity world. Yale University is partnering with other institutions to support the Secure and Trustworthy Cyberspace Program, a research program supported by the National Science Foundation. That program is working on initiatives like the creation of a confidential computing center, making a secure software supply chain and working to improve computing in marginalized communities.

In addition to the programs offered through NEBHE’s Tuition Break, five Massachusetts universities offer bachelor’s degrees in a cybersecurity-related field as well as two in Connecticut, two in Vermont, three in Maine, three in Rhode Island and one in New Hampshire, according to Cybersecurity Guide. Various other associate, master’s and doctoral degrees in cybersecurity fields are also available at New England HEIs.

Cox, of CCCC, also spoke about the school’s partnership with Bridgewater State University, which is developing a cyber range to simulate and test cybersecurity networks. This cyber range will allow students and professionals to perform mock cybercrime investigations to better prepare for any situation.

This is unlikely the last you’ll read on the complex challenges of cybersecurity in The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Viktoria Popovska is a NEBHE journalism intern and a junior at Boston University.

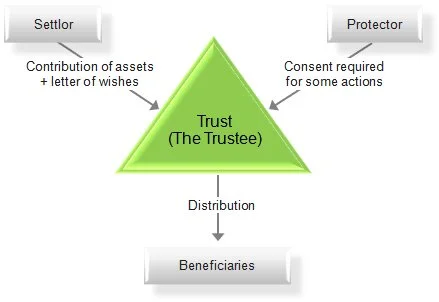

Trust traumas

Graphic by Anja Bauer

Berkshire Cotton Mills, in Adams, Mass., in the 19th Century, part of a predecessor operation of Berkshire Hathaway.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Most people enjoy reading about rich heirs to family fortunes fighting via nasty lawsuits over inherited money, which is usually held in complex trusts. Thus it has been with the widow of Michael Metcalf (who died in 1987) and their three children, who are suing her lawyers. Michael Metcalf ran the late-lamented big multimedia company The Providence Journal Co. Then there are a couple of Chace family cousins in Providence whose family owned Berkshire Hathaway, an old New England textile company that Warren Buffett turned into a kind of mutual fund for rich people.

Most people don’t have much money, and many live paycheck to paycheck. It makes them feel a bit better to see wealthy people angry and unhappy, though these privileged folks, often what the late Providence Mayor Vincent Cianci crudely called simply members of “the lucky sperm club,’’ almost always stay rich, and thus happier than most people.

Hit these links for details on the aforementioned fights:

https://www.golocalprov.com/business/Billionaires-Legacy-Chace-Family-Battle-Over-Control-of-Hundreds-of-Milli

Rob Smith: Ferries, charter boats along East Coast may have to slow down to protect endangered whale species

The New London, Conn., ferry terminal, which serves the Cross Sound Ferry and the Block Island Express, as viewed from across the Thames River. Both ferry services would be affected by proposed federal rules to help protect North Atlantic Right Whales.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

NARRAGANSETT, R.I.

Ferries and charter boats might have to move a lot slower along the New England coast during the off-season if federal regulators accept new nautical speed limits to protect an endangered species of whale.

Officials with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have proposed restricting existing nautical speed limits to 10 knots per hour for all vessels longer than 35 feet. If approved, the new rule would go into effect between Nov. 1 and May 30 and apply to all vessels sailing along the Atlantic seaboard from Massachusetts to North Carolina.

The rule is intended to curb the amount of vessel strikes on the Atlantic’s already limited North Atlantic Right Whale population, which is close to extinction. NOAA estimates at least four right whales have died from colliding with marine vessels since 2017.

“The biggest impact to charter boats is the loss of fishing time for our clients,” said Capt. Rick Bellavance, president of the Rhode Island Party and Charter Boat Association. “If we’re driving 10 miles an hour instead of 15, that’s 5 miles of travel every hour. It could be a half hour or an hour each day of less fishing and more driving.”

The off season isn’t quite as off it used to be. Bellavance says more and more customers charter boats to fish for tautog, also known as blackfish, which has had a resurgence thanks to, among other things, careful conservation by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), and is almost an attraction for the state in November and December.

Daily ferry service to Block Island could also be curtailed under the new rules. Currently the Block Island Ferry runs eight hour-long trips from the Port of Galilee to the island and back every weekday, with the average vessel speed clocking 16 knots per hour. Under the new restrictions, the daily ferry ride could take upwards of 90 minutes per one-way trip, with a reduced number of trips per day.

Block Island Ferry declined to comment for this article.

Protecting the right whales

Considered by NOAA to be “one of the world’s most endangered large whale species,” North Atlantic Right Whales feed in coastal waters ranging from New England to Newfoundland from spring to autumn. They then migrate to calving grounds off the southern United States, near the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida.

As of 2021 it is estimated there are only 350 North Atlantic Right Whales left worldwide. Once a plentiful species throughout the Atlantic, their populations were culled over the centuries due to aggressive whale hunters in the Northeast, who called them “right whales” because they were easily killed and their corpses floated to the surface.

Now right whales are protected under federal law and the Endangered Species Act, but the population has struggled to bounce back, with only an estimated 42 calves being born since 2017. Overall the right whale population has significantly declined since 2010, and 54 right whales have died or been seriously injured since 2017.

The real threat to right whales is no longer crusty old New England fishermen. According to federal officials, the real threat comes from entanglement in commercial fishing nets and vessel collisions. NOAA estimates over 85 percent of all right whales have been entangled in fishing nets at least once. The agency also estimates at least four whales have died because of vessel collisions since 2017 — and that number may be higher. NOAA estimates two-thirds of whale deaths go unreported.

“Collisions with vessels continue to impede North Atlantic right whale recovery. [Vessel speed limits are] necessary to stabilize the ongoing right whale population decline, in combination with other efforts to address right whale entanglement and vessel strikes in the U.S. and Canada,” said Janet Coit, assistant administrator for NOAA Fisheries.

Speed limits to curb collisions and protect right whales have existed since 2008, but the restrictions limited them to narrow geographic areas – for Rhode Island it only applied in waters south of Block Island, not affecting most marine traffic going in and out of Narragansett Bay – and ships greater than 65 feet long.

A risk analysis performed by NOAA suggested expanding vessel speed restrictions in the areas of highest risks could reduce right whale mortalities from vessel strikes by 27.5 percent.

The economic impact would also be minimal, according to NOAA. The agency’s economic impact report estimated the direct costs and impacts on transit times would cost the economy $28.3 million to $39.4 million annually, with much of that amount borne by the commercial shipping industry.

RIDEM, which owns and maintains the Port of Galilee, estimated the impact on commercial fishing vessels operating out of the port would be minimal. “Vessels in that size range aren’t traveling much faster than 10 knots anyway, even when transiting,” said DEM spokesman Mike Healey.

Not all agree. Bellavance thinks it will hurt the charter boat owners, who need the most business.

“There’s a smaller group of folks who do this to provide for their families, that’s their job,” said Bellavance. “Those are the ones that are impacted when you start to mess with the winter season, cause they’re still trying to go fishing year-round.”

NOAA is accepting public comment on the proposed rule until the end of October.

Rob Smith is an ecoRI staffer.

'Fear of clutter'

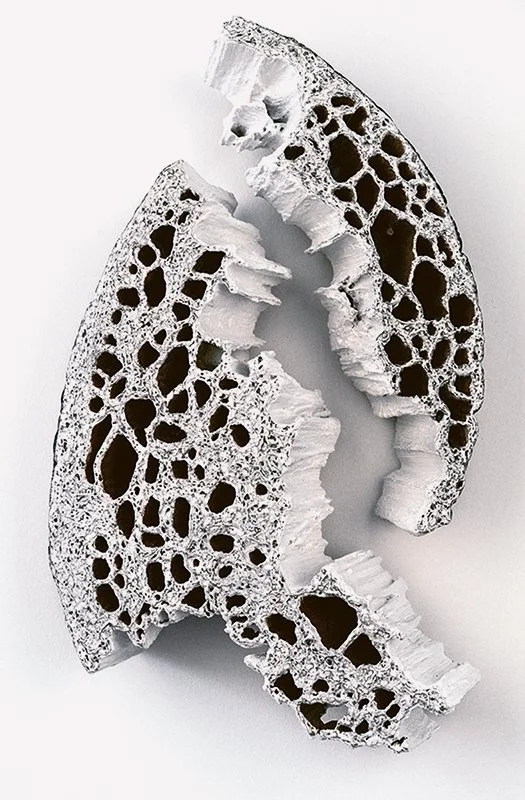

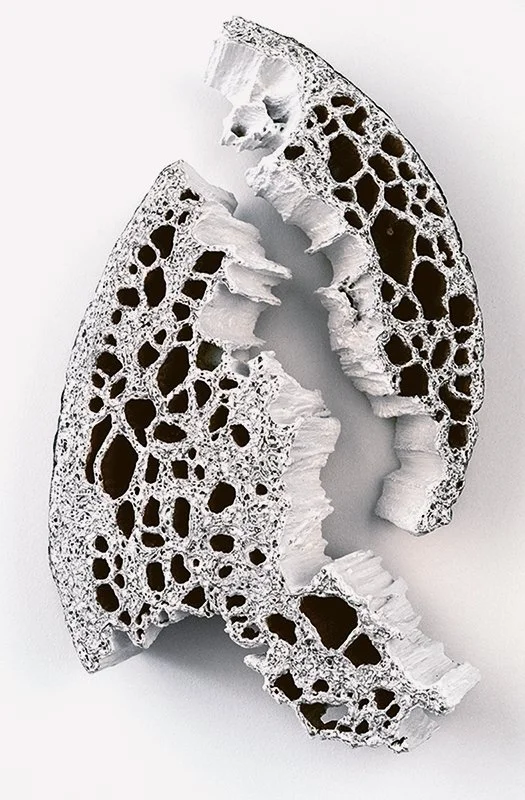

From “Ataxophilia,’’ Boston-based Zoe Friend’s show at Boston Sculptors Gallery Nov. 9-Dec. 11.

The gallery explains:

“A play on the term ataxophobia, a clinical condition described as ‘a fear of clutter or messy surroundings,’ the exhibition features assemblage sculptural works exploring the fetishization of objects through the artist’s baroque-inspired maximal aesthetic.’’

Western society defines us by our consumption, our belongings and now, very much by our waste. Focusing on the consumer sublime as well as examining the intersection of our relationship with nature and societal detritus, Friend presents highly ornate and sumptuous motifs juxtaposed with the mundane disposable materials from which they are made. Assembled from items such as plastic utensils, cheap costume jewelry, and fake fauna, the artist strips these elements of all familiar color cues, allowing the viewer to experience form before discerning the materials.

Friend has let this fear of things and her ever-evolving relationship with compulsion guide what she calls “an encapsulation of my own consumer anxieties,” laid bare in the collection of over-embellished objects which tell the story of our own excesses.

‘Enigmatic languages’

“Presence/Absence” (wooden found object with encaustic, sumi ink, cold wax), by Hanover, N.H.-based artist Lia Rothstein

Her artist statement says:

“I am fascinated by the complexity of the natural world and our own human anatomy. As an artist I have continually explored textures and abstracted forms, negative and positive spaces, light and shadow, linear elements that convey both connectedness and disconnection and, more recently, permanence and fragility. The calligraphic lines and the spaces in between them that I observe in the landscape and in my research about the brain and how we think, process information, and form memories feel like enigmatic languages to me, unique unto themselves, endlessly exquisite yet tenuous. Using waxes and other art materials I feel I can extend the meaning of my work beyond literal representation by creating layers of meaning, metaphor, translucency, physicality and temporality.’’

Students playing cricket at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H., in 1793. The town is mostly known for hosting Dartmouth, chartered in 1769 and whose predecessor institution was Moor’s Indian Charity School, founded in Lebanon, Conn., in 1754.

Josiah Dunham (artist), S. Hill (engraver)

Dartmouth’s Hood Museum of Art.

‘It tasted like winter’

— Photo by Kembangraps

”…inspired by ants

I tasted the sap

that oozed in great drops

from the bark of the pine

it tasted like its needles smelled

like winter like mountains or early morning….’’

— From “Amber Necklace,’’ by Cheryl Savageau, a Worcester, Mass., native of Abenaki and French-Canadian background