A coast for artists

"Taking a Day Off'' (acrylic), by Del-Bourree Bach, in the group show "Maine Stories,'' at Sarah Powell Fine Art, Madison, Conn.

Along a dangerously exposed stretch of expensive houses in Madison, Conn., on Long Island Sound. (Photo by Léo Schmitt)

The gallery says that the show “celebrates a landscape tradition which has captivated generations of artists for over 100 years, from Thomas Cole and Frederick Church to Winslow Homer and Andrew Wyeth. A vital place of artistic inspiration, Maine’s rugged coastline, churning seas, iconic lighthouses, vivid buoys, lobster boats and historic harbors have been subjects for some of America’s finest painters.’’

Ceating a reservoir and a wilderness

Looking north up the Swift River Valley from Quabbin Hill, in central Masssachusetts, on Aug. 14, 1939, shortly before a dam started to create the huge lake that was to be the major water supply for Greater Boston.

“In front of me stretched the water of the Quabbin {Reservoir}. It was for this water that the Swift River Valley was flooded. It was because of this water that the wilderness, with its eagles and its extensive woodlands and abandoned cellar holes, exist in the Quabbin region.’’

— From Quabbin, The Accidental Wilderness (1981), by Thomas Conuel

The Quabbin Reservoir in November 2005.

Risking it all

From Robert Whitcomb “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Eileen Warburton’s new book, Chasing Chance: Stories of the Peirce-Prince Families in America, is riveting American history structured through the interwoven narratives of two families who arrived in New England from England in “The Great Migration’’ of Puritans to New England, 1620-1640.

“Chance” in this context means accepting risk.

This is not some dry genealogical tome. Rather, this brilliantly researched, written and illustrated work narrates the sagas of memorable characters, many heroic, some not, in ways that can suggest life lessons for everyone. What to do, what not to do.

The cast of characters include austere and deeply religious Puritans, alleged witches, sea captains, Confederate officers, business moguls, scholars, artists, statesmen, war heroes and founders of towns, states, and companies. They’re never shown as stock figures but as idiosyncratic people in the round, with anger, occasional ruthlessness and other problematic elements mixed in with such admirable qualities as courage in the face of high, even lethal risks, ingenuity, generosity, civic leadership and plenty of romance.

‘Sci-Fi Sufism’

"Praying A.N.G.E.L.S." (foam print), by Saks Afridi, in his show ""SpaceMosque,'' at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum & Art Center, through Oct. 19.

He explains:

“My work exists in a genre I term as ‘Sci-Fi Sufism’, which is about discovering galaxies and worlds within yourself. I try to visualize this search by fusing mysticism and storytelling. I make art objects in multiple mediums and I draw inspiration from Sufi poetry, South Asian folklore, Islamic mythology, science fiction, architecture and calligraphy.’’

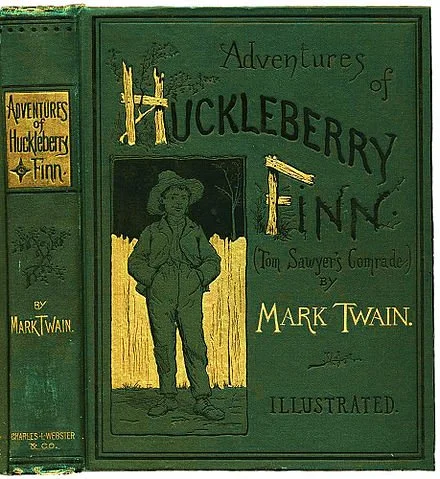

Chris Powell: The misnamed 'Banned Books Week'; about that bus highway

Mark Twain's famed novel has been banned in some American schools because of its racial language.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Last week was what librarians and leftists in Connecticut and throughout the country call Banned Books Week. A more accurate name for it would be Submit to Authority Week.

The week is misnamed because in the United States there are no banned books at all -- no books whose publication and possession are forbidden by government. Banned Books Week has been contrived by librarians and leftists to intimidate people out of criticizing certain books that librarians and school administrators have chosen for inclusion in school libraries, curriculums, and public libraries. The objective is to prevent libraries and schools from ever having to answer to anyone for their choices.

The selection of every book for a library or curriculum is always a matter of judgment. But the promoters of Banned Books Week would have the public believe that the choices made by librarians and school administrators are always right, and that anyone who questions these choices is a follower of Hitler or, worse, Donald Trump.

Some criticism of library and curriculum choices is nutty. Two great works of American literature that have helped to defeat racism -- Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird -- are sometimes targeted by people who can't get past the occasional racist language in them.

But these days most books whose inclusion in schools and libraries are challenged involve homosexuality and transgenderism, and these are fairly challenged at least in regard to their appropriateness for children, especially amid the mental illness that is worsening among them.

This doesn't mean that such books should be excluded automatically but that their appropriateness should be settled by thoughtful review and discussion. Calling a book's critics "book banners" and a book's advocates "groomers," as is common in these controversies, is not thoughtful.

The great irony of Banned Books Week is that as a practical matter its promoters are themselves the biggest book banners. That is, with a virtually infinite number of books in the world, librarians and school administrators reject thousands of books for every one they include.

Of course not all books can be included in any library or curriculum. Do the choices that are made give a politically balanced view of the world and academic subjects or a politically skewed and propagandist one?

If Banned Books Week succeeds, no one will ever know -- which is the idea.

Shelter along the CTfastrak route

The once-controversial bus highway between Hartford and New Britain, CTfastrak, has been operating for 10 years, and this week Connecticut's Hearst newspapers sought to determine if, after a construction cost of more than half a billion dollars, the busway can be considered a success.

CTfastrak has turned 10 and seen an increase in riders from a pandemic dip

CTfastrak has turned 10 and seen an increase in riders from a pandemic dip

CTfastrak has turned 10 and seen an increase in riders from a pandemic dip

CTfastrak has turned 10 and seen an increase in riders from a pandemic dip

The state Transportation Department says the highway had 2.8 million riders in 2016, its first full year of operation, reached a peak of 3.3 million riders in 2019, and then, amid the Covid-19 epidemic, fell to about 2 million riders in 2021 and has been slowly increasing since.

But the chief of the department's Bureau of Public Transit, Ben Limmer, was unable to provide information crucial to a judgment on the project. While it stands to reason that the bus highway has reduced automobile commuting between Hartford and New Britain, the department says it has no data on that. More concerning is that the department can't or won’t say how much each CTfastrak rider is being subsidized by state government.

"We do what we can to make sure fares are affordable," Limmer said. "I assume fares have not kept up with inflation, so we’re probably flat or slightly up on subsidies."

All modes of transportation -- sidewalks, streets and highways, trains, and airplanes -- are subsidized by government in some way. But now that the epidemic-induced trend of working from home has greatly reduced commuting, CTfastrak is even more questionable than it was when it began.

Does the Transportation Department want to know what CTfastrak’s operating costs are and how much riders are being subsidized? It doesn't seem to want the public to know.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Trying to recognize absence

At Rhonda Smith’s show, “Undiscovered Country,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Oct. 29-Dec. 1. She is based in Boston and Biddeford Pool, Maine.

The gallery says “‘Undiscovered Country’ derives from various influences: sea tales, myths, poems, industrial and natural elements, medieval imagery, photographs, and contemporary statistics. These influences emerge during the creation of each piece. Rhonda Smith relies on the tactile process of shaping, molding, and assembling materials to give form to her ideas. Initial concepts often remain skeletal or merely impulsive, while the true essence of a piece develops through the tactile process of listening to what her hands transmute.

”The sculptures and installations, with their broad mix of materials and techniques, represent both disappearance and appearance—experiences that are simultaneously deeply satisfying and fragile; Will humans disappear and nature survive? Is our possibility now in recognizing absence? Smith remains increasingly aware that, in the face of crumbling realities, only her openness to the undiscovered will have significance. For Smith, this is what art can achieve: guiding us towards new ground.’’

Llewellyn King: Trove of latters takes us inside the Civil War

Some American Civil War related pictures via Wikipedia

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Just when you thought that every word that could be written about the American Civil War had been written, every book published, along comes an exciting collection of new information.

Such a happening comes as a new book — still seeking a publisher — from Civil War aficionado J. Mark Powell, the editor at InsideSources, a syndication service.

Before electronic recording devices, letters were the eyewitnesses to history. The discovery of a trove of these is a light beamed into the past.

Powell’s book is a compilation he has made in 20 years of seeking, collecting, chasing down, and sometimes buying unpublished letters from the war. He has collated these and provided just enough annotation to make them an easy and engrossing read.

In all there are nearly 500 letters from every social strata affected by the tumult — from a slave to many tender notes between families torn apart and sometimes divided between North and South. It is history in the raw, modified only by Powell’s scholarship and loving curation.

The letters were written between husbands and wives, between lovers, between parents and children, and between brothers. They provide untrammeled truth or truth reflected by the station of the writers.

It is truth that hasn’t been adulterated for political purposes, then or now, as often happens, with the weaponizing of history.

These letters take the reader into the war, its hope and its horror. It is life as it was lived by ordinary people, soldier and wife, mother and child between 1861 and 1865, through the eyes of people who lived the war, and sometimes died.

Powell told me, “This is the first account of its kind, to the best of my knowledge. It is just a completely unique approach.

“This isn’t a textbook recitation of names and dates and places. I tried to capture how it felt to live through those terrible times. The pride, the hopes, the fears, the uncertainty, and even the humor is all in this collation of the letters for those who endured the war on both sides.”

There are no famous names here, no excerpts from famous generals or major historical figures. Rather, these are the everyday people who lived through the war and, in some cases, didn’t survive.

Powell is a seasoned journalist who worked for several local TV stations, CNN, and on Capitol Hill before alighting at InsideSources. He is also the author of a novel and has collaborated on another. He has given much of his life to studying the Civil War — a fascination which began as a 10-year-old.

Powell said his work is also a cautionary tale for 2024, “because the war resulted from two sides that had dug in their heels and refused to budge. Very much the same way America is suffering the hardening of the political arteries right now.”

In one letter from his book, a woman named Genevieve Byrne Runyon lost her husband, James, an officer in the 26th Iowa Infantry in 1862. He had been dead for nearly three years when his regiment returned home.

This is her anguish as she related it to her late husband’s brother in a letter dated Dewitt, Iowa, August 18, 1865:

“I suppose you would like to know how I am getting along. I had my father move into my house and I am keeping house for him. Yet I feel like a wanderer looking for someone that I’ll never see again. It feels foolish to be ever complaining, but I cannot help it. I could write forever on the subject.

“How I felt when the remainder of his regiment returned without him, I cannot describe. I felt I had lost him forever on this earth. Now that the cruel war is over and I look back and see the many lonely homes, I wonder what it all meant.”

Powell, who writes the weekly syndicated, historical column “Holy Cow,” told me, “I’ve had that letter for over 20 years now, and that last line still haunts me every time I read it.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

White House Chronicle

Amy Waxman: Nurses’ aides say they’re plagued by PTSD from work during COVID at Mass. facility

The Massachusetts Veterans Home in Holyoke.

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (KFF)

One evening in May, nursing assistant Debra Ragoonanan’s vision blurred during her shift at a state-run Massachusetts veterans home. As her head spun, she said, she called her husband. He picked her up and drove her to the emergency room, where she was diagnosed with a brain aneurysm.

It was the latest in a drumbeat of health issues that she traces to the first months of 2020, when dozens of veterans died at the Soldiers’ Home in Holyoke, in one of the country’s deadliest COVID-19 outbreaks at a long-term nursing facility. Ragoonanan has worked at the home for nearly 30 years. Now, she said, the sights, sounds, and smells there trigger her trauma. Among her ailments, she lists panic attacks, brain fog, and other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition linked to aneurysms and strokes.

Scrutiny of the outbreak prompted the state to change the facility’s name to the Massachusetts Veterans Home at Holyoke, replace its leadership, sponsor a $480 million renovation of the premises, and agree to a $56 million settlement for veterans and families. But the front-line caregivers have received little relief as they grapple with the outbreak’s toll.

“I am retraumatized all the time,” Ragoonanan said, sitting on her back porch before her evening shift. “How am I supposed to move forward?”

Covid killed more than 3,600 U.S. health-care workers in the first year of the pandemic. It left many more with physical and mental illnesses — and a gutting sense of abandonment.

What workers experienced has been detailed in state investigations, surveys of nurses, and published studies. These found that many health-care workers weren’t given masks in 2020. Many got COVID and worked while sick. More than a dozen lawsuits filed on behalf of residents or workers at nursing facilities detail such experiences. And others allege that accommodations weren’t made for workers facing depression and PTSD triggered by their pandemic duties. Some of the lawsuits have been dismissed, and others are pending.

Health-care workers and unions reported risky conditions to state and federal agencies. But the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration had fewer inspectors in 2020 to investigate complaints than at any point in a half-century. It investigated only about 1 in 5 covid-related complaints that were filed officially, and just 4 percent of more than 16,000 informal reports made by phone or email.

Nursing assistants, health aides, and other lower-wage health-care workers were particularly vulnerable during outbreaks, and many remain burdened now. About 80 percent of lower-wage workers who provide long-term care are women, and these workers are more likely to be immigrants, to be people of color, and to live in poverty than doctors or nurses.

Some of these factors increased a person’s COVID risk. They also help explain why these workers had limited power to avoid or protest hazardous conditions, said Eric Frumin, formerly the safety and health director for the Strategic Organizing Center, a coalition of labor unions.

He also cited decreasing membership in unions, which negotiate for higher wages and safer workplaces. One-third of the U.S. labor force was unionized in the 1950s, but the level has fallen to 10 percent in recent years.

Like essential workers in meatpacking plants and warehouses, nursing assistants were at risk because of their status, Frumin said: “The powerlessness of workers in this country condemns them to be treated as disposable.”

In interviews, essential workers in various industries told KFF Health News they felt duped by a system that asked them to risk their lives in the nation’s moment of need but that now offers little assistance for harm incurred in the line of duty.

“The state doesn’t care. The justice system doesn’t care. Nobody cares,” Ragoonanan said. “All of us have to go right back to work where this started, so that’s a double whammy.”

‘A War Zone’

The plight of health-care workers is a problem for the United States as the population ages and the threat of future pandemics looms. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy called their burnout “an urgent public health issue” leading to diminished care for patients. That’s on top of a predicted shortage of more than 3.2 million lower-wage health care workers by 2026, according to the Mercer consulting firm.

The veterans home in Holyoke illustrates how labor conditions can jeopardize the health of employees. The facility is not unique, but its situation has been vividly described in a state investigative report and in a report from a joint oversight committee of the Massachusetts Legislature.

The Soldiers’ Home made headlines in March 2020 when The Boston Globe got a tip about refrigerator trucks packed with the bodies of dead veterans outside the facility. About 80 residents died within a few months.

The state-run Soldiers’ Home in Holyoke, Massachusetts, was the scene of one of the country’s deadliest covid outbreaks at a long-term nursing facility. Scrutiny of the outbreak prompted the state to change the home’s name, replace its leadership, and agree to a $56 million settlement for veterans and their families. But front-line caregivers have received little relief as they continue to grapple with the trauma.(Amy Maxmen/KFF Health News)

The state investigation placed blame on the home’s leadership, starting with Superintendent Bennett Walsh. “Mr. Walsh and his team created close to an optimal environment for the spread of COVID-19,” the report said. He resigned under pressure at the end of 2020.

Investigators said that “at least 80 staff members” tested positive for covid, citing “at least in part” the management’s “failure to provide and require the use of proper protective equipment,” even restricting the use of masks. They included a disciplinary letter sent to one nursing assistant who had donned a mask as he cared for a sick veteran overnight in March. “Your actions are disruptive, extremely inappropriate,” it said.

To avoid hiring more caretakers, the home’s leadership combined infected and uninfected veterans in the same unit, fueling the spread of the virus, the report found. It said veterans didn’t receive sufficient hydration or pain-relief drugs as they approached death, and it included testimonies from employees who described the situation as “total pandemonium,” “a nightmare,” and “a war zone.”

Because his wife was immunocompromised, Walsh didn’t enter the care units during this period, according to his lawyer’s statement in a deposition obtained by KFF Health News. “He never observed the merged unit,” it said.

In contrast, nursing assistants told KFF Health News that they worked overtime, even with COVID because they were afraid of being fired if they stayed home. “I kept telling my supervisor, ‘I am very, very sick,’” said Sophia Darkowaa, a nursing assistant who said she now suffers from PTSD and symptoms of long COVID. “I had like four people die in my arms while I was sick.”

Nursing assistants recounted how overwhelmed and devasted they felt by the pace of death among veterans whom they had known for years — years of helping them dress, shave, and shower, and of listening to their memories of war.

“They were in pain. They were hollering. They were calling on God for help,” Ragoonanan said. “They were vomiting, their teeth showing. They’re pooping on themselves, pooping on your shoes.”

Nursing assistant Kwesi Ablordeppey said the veterans were like family to him. “One night I put five of them in body bags,” he said. “That will never leave my mind.”

Four years have passed, but he said he still has trouble sleeping and sometimes cries in his bedroom after work. “I wipe the tears away so that my kids don’t know.”

High Demands, Low Autonomy

A third of health-care workers reported symptoms of PTSD related to the pandemic, according to surveys between January 2020 and May 2022 covering 24,000 workers worldwide. The disorder predisposes people to dementia and Alzheimer’s. It can lead to substance use and self-harm.

Since COVID began, Laura van Dernoot Lipsky, director of the Trauma Stewardship Institute, has been inundated by emails from health care workers considering suicide. “More than I have ever received in my career,” she said. Their cries for help have not diminished, she said, because trauma often creeps up long after the acute emergency has quieted.

Another factor contributing to these workers’ trauma is “moral injury,” a term first applied to soldiers who experienced intense guilt after carrying out orders that betrayed their values. It became common among health care workers in the pandemic who weren’t given ample resources to provide care.

“Folks who don’t make as much money in health care deal with high job demands and low autonomy at work, both of which make their positions even more stressful,” said Rachel Hoopsick, a public-health researcher at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “They also have fewer resources to cope with that stress,” she added.

People in lower-income brackets have less access to mental-health treatment. And health-care workers with less education and financial security are less able to take extended time off, to relocate for jobs elsewhere, or to shift careers to avoid retriggering their traumas.

Such memories can feel as intense as the original event. “If there’s not a change in circumstances, it can be really, really, really hard for the brain and nervous system to recalibrate,” van Dernoot Lipsky said. Rather than focusing on self-care alone, she pushes for policies to ensure adequate staffing at health facilities and accommodations for mental health issues.

In 2021, Massachusetts legislators acknowledged the plight of the Soldiers’ Home residents and staff in a joint committee report saying the events would “impact their well-being for many years.”

But only veterans have received compensation. “Their sacrifices for our freedom should never be forgotten or taken for granted,” the state’s veterans services director, Jon Santiago, said at an event announcing a memorial for veterans who died in the Soldiers’ Home outbreak. The state’s $56 million settlement followed a class-action lawsuit brought by about 80 veterans who were sickened by covid and a roughly equal number of families of veterans who died.

The state’s attorney general also brought criminal charges against Walsh and the home’s former medical director, David Clinton, in connection with their handling of the crisis. The two averted a trial and possible jail time this March by changing their not-guilty pleas, instead acknowledging that the facts of the case were sufficient to warrant a guilty finding.

An attorney representing Walsh and Clinton, Michael Jennings, declined to comment on queries from KFF Health News. He instead referred to legal proceedings in March, in which Jennings argued that “many nursing homes proved inadequate in the nascent days of the pandemic” and that “criminalizing blame will do nothing to prevent further tragedy.”

Nursing assistants sued the home’s leadership, too. The lawsuit alleged that, in addition to their symptoms of long covid, what the aides witnessed “left them emotionally traumatized, and they continue to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.”

The case was dismissed before trial, with courts ruling that the caretakers could have simply left their jobs. “Plaintiff could have resigned his employment at any time,” Judge Mark Mastroianni wrote, referring to Ablordeppey, the nursing assistants’ named representative in the case.

But the choice was never that simple, said Erica Brody, a lawyer who represented the nursing assistants. “What makes this so heartbreaking is that they couldn’t have quit, because they needed this job to provide for their families.”

‘Help Us To Retire’

Brody didn’t know of any cases in which staff at long-term nursing facilities successfully held their employers accountable for labor conditions in covid outbreaks that left them with mental and physical ailments. KFF Health News pored through lawsuits and called about a dozen lawyers but could not identify any such cases in which workers prevailed.

A Massachusetts chapter of the Service Employees International Union, SEIU Local 888, is looking outside the justice system for help. It has pushed for a bill — proposed last year by Judith García, a Democratic state representative — to allow workers at the state veterans home in Holyoke, along with its sister facility in Chelsea, to receive their retirement benefits five to 10 years earlier than usual. The bill’s fate will be decided in December.

Retirement benefits for Massachusetts state employees amount to 80 percent of a person’s salary. Workers qualify at different times, depending on the job. Police officers get theirs at age 55. Nursing assistants qualify once the sum of their time working at a government facility and their age comes to around 100 years. The state stalls the clock if these workers take off more than their allotted days for sickness or vacation.

Several nursing assistants at the Holyoke veterans home exceeded their allotments because of long-lasting COVID symptoms, post-traumatic stress, and, in Ragoonanan’s case, a brain aneurysm. Even five years would make a difference, Ragoonanan said, because, at age 56, she fears her life is being shortened. “Help us to retire,” she said, staring at the slippers covering her swollen feet. “We have bad PTSD. We’re crying, contemplating suicide.”

Certain careers are linked with shorter life spans. Similarly, economists have shown that, on average, people with lower incomes in the United States die earlier than those with more. Nearly 60 percent of long-term-care workers are among the bottom earners in the country, paid less than $30,000 — or about $15 per hour — in 2018, according to analyses by the Department of Health and Human Services and KFF, a health-policy research, polling, and news organization that includes KFF Health News.

Fair pay was among the solutions listed in the surgeon general’s report on burnout. Another was “hazard compensation during public health emergencies.”

If employers offer disability benefits, that generally entails a pay cut. Nursing assistants at the Holyoke veterans home said it would halve their wages, a loss they couldn’t afford.

“Low-wage workers are in an impossible position, because they’re scraping by with their full salaries,” said John Magner, SEIU Local 888’s legal director.

Despite some public displays of gratitude for health care workers early in the pandemic, essential workers haven’t received the financial support given to veterans or to emergency personnel who risked their lives to save others in the aftermath of 9/11. Talk show host Jon Stewart, for example, has lobbied for this group for over a decade, successfully pushing Congress to compensate them for their sacrifices.

“People need to understand how high the stakes are,” van Dernoot Lipsky said. “It’s so important that society doesn’t put this on individual workers and then walk away.”

Amy Maxmen is a KFF journalist.

Inspired by Boston landmarks

"IYKYK" (wood, plastics), by Christopher Abrams, in his show "IYKYK," at Boston Sculptors Gallery, Oct. 3-Nov. 3.

The famous sign at Kenmore Square, in Boston.

The gallery says:

“The show is a series of small-scale sculpture based on iconic landmarks and forgotten histories in the Boston area. While Abrams continues to concentrate on small-scale representational concerns, the artist revisits and redirects his focus, abandoning the intense fealty to detail that characterizes his earlier miniature efforts, in favor of finding essential, meaningful symbols and imagery.

“Taking inspiration from his hometown, Abrams draws on the events and visual vocabulary that create and distinguish the unique identity of Greater Boston. Selecting and amplifying elements of the local, shared visual fabric, Abrams weighs how seemingly minor details can allude to a rich, shared narrative.’’

All is perfect in Boston

On the Commonwealth Avenue Mall, in Boston's Back Bay.

The people’s lives in Boston

Are flowers blown in glass;

On Commonwealth, on Beacon,

They bow and speak and pass.

No man grows old in Boston,

No lady ever dies;

No youth is ever wicked,

No infant ever cries.

From E.B. White’s poem “Boston Is Like No Other Place in the World Only More So,’’ published in the Sept. 23, 1949 New Yorker. Here’s the whole poem.

‘New meaning from fragments’

Broken Soldier” (detail), (jacquard tapestry with laser-cut painted felt letters with rescue blankets suspended on aluminum structures), by Katarina Weslien, in her show "I Forgot to Remember,'' at the Maine Center for Contemporary Art, Rockland, Maine, Sept. 28-May 4.

— Photo courtesy of Kyle Dubay. At Center for Maine Contemporary Art

Suzanne Weaver, curator of the show, says:

“At the heart of Weslien’s intelligent, insightful, and sensorial exhibition are the struggles and joys of finding new meaning through the coming together of fragments of our experiences, memories, loves, and desires. The importance of being present, aware of the physical and poetic interconnectedness of all life and to act consciously and creatively in finding solutions that shape us and our surroundings in positive and beneficial ways.”

Weslien lives on Peaks Island, Maine, in Casco Bay.

On an inland coast

The 1872 U.S. Coast Survey nautical chart/map of Burlington, Vt. It covers the urban center of Burlington as well as the surrounding areas as far south as Shelburn Point and as far north as as Rock Point. Offers exceptional detail, with important building, streets and property lines shown. In Lake Champlain there are countless depth soundings as well as notes on reefs and shoals.

Northern in ethnicity, too

--The Pine Tree State is still reportedly the whitest state in the Union but as everywhere else is becoming more diverse, especially in the Portland area.

Graphic by Noahnmf

Mordechai Gordon: On self-forgiveness

-- Photo by Karamveer Singh

HAMDEN, Conn.

As the Jewish High Holidays approach, which begin with Rosh Hashanah and continue with Yom Kippur, the theme of forgiveness keeps coming to my mind.

The 10 days from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur are referred to in the Jewish tradition as the days of repentance, or the days of awe. During this period, Jews who observe the holidays implore God to respond to their sins with mercy, while also requesting forgiveness from anyone those individuals may have wronged in the past year.

Most conversations about forgiveness focus on the meaning and value of forgiving others. Douglas Stewart, a philosopher of education who has researched forgiveness extensively, writes that to forgive implies a willingness to let go of our negative emotions or hard feelings and to adopt in their place a more generous and compassionate attitude toward our wrongdoers.

Other philosophers have pointed out that the benefits of forgiveness include overcoming resentment, restoring relationships and setting a wrong to rest in the past – without vengeance. As such, to forgive should be considered morally valuable and admirable.

But what about self-forgiveness? Is it morally valuable, or just something we do to make ourselves feel better? And what is self-forgiveness, anyway?

As a philosopher of education, some of my own research has wrestled with these questions.

During Tashlich, a ceremony on Rosh Hashanah, people symbolically cast away their sins by throwing bits of bread into flowing water. Bill Greene/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Defining self-forgiveness

Self-forgiveness means managing to work through painful feelings such as guilt, shame and deep disappointment with ourselves. It entails transforming negative attitudes, such as contempt, anger and shame, into more positive emotions such as respect and humility.

It is important to recognize, however, that a wrongdoer cannot simply reject shame: They must confront it. Moral philosophers such as Byron Williston assert that people who have deeply wronged others, such as betraying a loved one, need to experience shame and take responsibility for their actions – such as asking for forgiveness. Otherwise, an attempt at self-forgiveness is not likely to be meaningful.

Finally, we need to keep in mind that self-forgiveness does not imply someone has extinguished all the negative feelings directed at themselves or is done with self-reproach. This would amount to an impossible goal.

Rather, as philosopher Robin Dillon pointed out, self-forgiveness suggests that someone is no longer being consumed or overwhelmed by those negative feelings. In short, it is possible to forgive ourselves and still view ourselves with a demanding and critical eye.

Moral development

Getting there, though, is not easy. Self-forgiveness entails working through a rigorous process of coming to terms with wrongdoing.

According to ethicist Margaret Holmgren, that process includes at least four steps: acknowledging that what we did was wrong; coming to terms with why it was wrong; allowing ourselves to experience grief and self-resentment at having injured another person; and, finally, making a genuine effort to correct the attitudes that led to the harmful act and making amends to the victim.

In other words, confronting negative emotions, attitudes and patterns is essential prior to attempting to restore relationships with others. Only once we are able to relax the preoccupation with guilt and shame, and to genuinely forgive ourselves, can we meaningfully contribute to relationships as liberated and equal partners – especially in ongoing ones, such as with family and friends.

Self-forgiveness isn’t just self-serving. Jasmin Merdan/Moment via Getty Images

Of course, there are cases in which the offense is so vast, such as genocide, that no individual can make full restitution or provide an adequate apology for the wrong.

There are other times when an apology is impossible. Perhaps victims are dead; perhaps a direct apology would retraumatize them or do more harm than good.

In those cases, I would argue, an offender can still attempt to work toward self-forgiveness – acknowledging not only the victim’s intrinsic worth but their own, regardless of their ability to make amends. This in itself is moral growth: appreciating that neither is a mere object that can be manipulated or abused.

The take-home point, I would argue, is that going through the process of self-forgiveness is morally beneficial. It can not only liberate people who tend to reproach themselves incessantly, but it can enhance their ability to relate ethically toward others – to acknowledge wrongdoing, while simultaneously affirming their own value.

Most people have experienced at least one situation in which they inflicted pain on someone else and recognized that their words or actions caused harm. In such situations, we also often feel ashamed of ourselves and attempt to apologize or make amends.

Yet I hope that during this High Holiday season we keep in mind that self-forgiveness should also be considered essential. If moral development means a process in which our self-awareness and character mature, then acknowledging wrongdoing and experiencing shame, followed by self-forgiveness, are indispensable for that process.

Mordechai Gordon is a professor of education at Quinnipiac University, in Hamden.

Mordechai Gordon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment

Big picture show

From 101-year-old painter Robert O. Thornton’s stunning show of mostly large canvases at the gallery of the Central Congregational Church in Providence. For many years he was the official photographer of the Museum of Art at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Moving to mellow

A portion of the north-central Pioneer Valley in South Deerfield, Mass., as it will look in several weeks.

Chris Powell: How many jobs were actually created by Conn. state fund? Stop companies from looting hospitals

Chimera. Apulian red-figure dish, ca. 350-340 BC

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut's state auditors are on a roll with their critical report about state government's "venture-capital firm," Connecticut Innovations, which was published the other day soon after the critical audits about expensive management failures at Central Connecticut State University, the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, and the Correction Department.

The problem with Connecticut Innovations, the auditors say, is that the agency, which spends tens of millions of dollars investing in new companies in the state, can't be sure that the companies have produced all the jobs they promised to produce with state government's investment. According to the auditors, Connecticut Innovations says verifying the job numbers would require auditing the companies and the companies can't afford it. Connecticut Innovations adds that while the state Labor Department has data about employment at the companies, it's always out of date.

This explanation is weak. Surely without much cost the subsidized companies can quantify their employment at regular intervals and identify their employees by names, address, and hours worked. Connecticut Innovations then could do spot checks about the claimed employees. This wouldn't be foolproof but it would be better than simply accepting the data provided by the subsidized companies as Connecticut Innovations does now.

Connecticut Innovations says it will try to figure something out, though the issue may be forgotten unless the General Assembly presses it.

The auditors' report on Connecticut Innovations should be taken by the legislature as an invitation to reconsider the agency in its entirety. For even if the job-creation data reported to Connecticut Innovations could be verified comprehensively, it would not mean the agency's subsidies were essential.

For the world is full of banks and investment firms that finance new businesses. Who can be sure that the jobs at companies subsidized by Connecticut Innovations couldn't have been created anyway with private financing? Why does state government need to get into the venture capital business any more than it needs to get into any other business?

Of course a venture capital firm operated by state government can provide one thing more readily than a private venture-capital firm can -- political patronage for those who run the government.

In any case if Connecticut had an economic and political climate more favorable to business and wealth creation than to employment by and dependence on government, state government might not feel as compelled to play favorites and subsidize certain businesses. A better economic and political climate would be the best innovation of all.

Better late than never -- and in the middle of his campaign for re-election -- Connecticut U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy has noticed the looting of Waterbury, Manchester Memorial, and Rockville General hospitals by the California-based investment company, Prospect Medical Holdings, which purchased them from their nonprofit operators in 2016 and began mortgaging their property and stripping their assets to pay big dividends to its investors.

This kind of thing has become a nationwide racket, and Murphy cited the Connecticut angle last week during a Senate hearing about the bankruptcy of Steward Health Care, a for-profit company that recently ran three hospitals in Massachusetts into bankruptcy.

Murphy asked: "How have we let American capitalism get so far off the rails, so unmoored from the common good, that anybody thinks it's OK to make a billion dollars off of degrading health care for poor people in Waterbury, Connecticut?"

The answer is simple. It is less a matter of capitalist greed than government's negligence. That is, in Connecticut and elsewhere government has allowed profit-making companies to acquire nonprofit hospitals and extract for profit the decades of public charity that built them.

Federal and state law could prohibit such transactions. So how about it, Senator, Gov. Ned Lamont, and state legislators? And Senator, how about returning the $2,500 campaign contribution you received from Prospect's political action committee in 2017, a year after it acquired the Connecticut hospitals, a contribution reported this week by political blogger Kevin Rennie?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

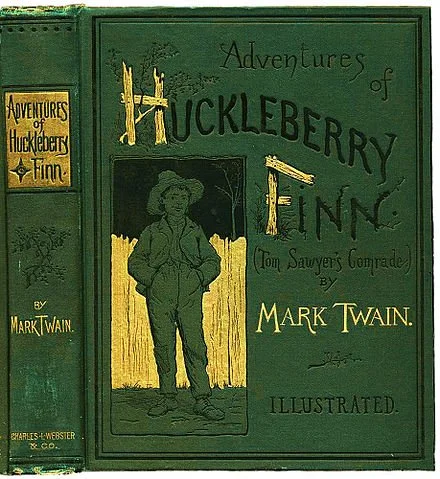

Creative destruction

"Modern Religion (They Know Not What They Do)"(cut paper collage using 18th Century copper plate engraving, 19th Century bookplates, and found paperboard), by Sarah Seaver, in the group show "Brotherhood of Thieves,'' at the Corner Gallery, Jaffrey N.H., Oct. 4-Nov. 16.

The gallery say the show is an “exhibition of collage/assemblage from across New England examining the relationship between the art forms and their materials. Focused on original source materials ranging from musical instruments to oil paintings, the show explores the artwork’s ability to consume and even destroy rare, storied matter while taking on its unique substance, history, and venerability.’’

Clay Memorial Library in Jaffrey, with, as in so many New England towns, a statue of a Civil War soldier in front of it.

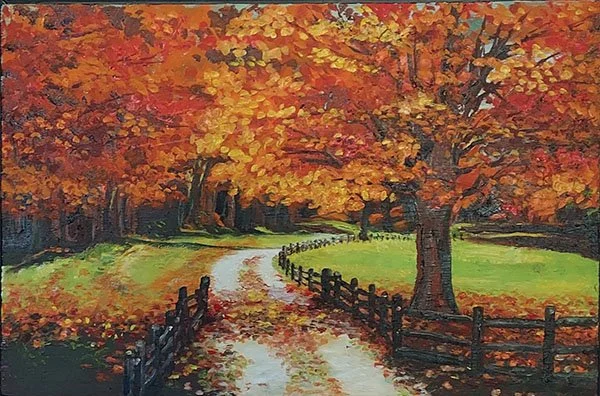

They go fast

”A Walk Among the Maples” (oil on board), by Vivian Zoe, at in the group show “Abundant Autumn, '' at Spectrum Art Gallery, Essex, Conn., Sept. 27-Nov . 9.

Boston car thieves favor Hondas

Excerpted from The Boston Guardian

(New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

Boston’s car thieves are setting themselves apart from the rest of the country with their preferred targets, going after Hondas and the traditionally targeted pickups while their peers shift to Hyundais and Kias.

Data from the Boston Police Department shows Honda as Boston’s highest-risk car brand, with 113 Hondas stolen since the beginning of 2024.

Almost half of those have been Honda Accords, far and away the most popular target for car thieves at 47 thefts. The second highest make at 26 thefts was still a Honda, the Honda CR-V.

That’s a marked departure from national trends, where data from the National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB) suggests full size pickups have been almost kicked off the 2023 leaderboards in the scramble for cars from Hyundai and Kia.

Viral social media posts showing security flaws in those brands saw crimes involving them skyrocket 10,000 percent since 2020. Hyundai Elantras and Sonatas took first and second place respectively, followed by the Kia Optima.