In search of cheap help

View of Pack Monadnock Mountain from Temple Mountain, on the eastern side of Sharon, N.H. Temple Mountain was the site of the privately owned Temple Mountain Ski Area from 1938 to 2001, when it was closed. In 2007, the state took it over and turned it into a park. The ski area’s proximity to Greater Boston made it very popular in its heyday, in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

— Photo by Ken Gallager

“I don't mind America becoming a Third World country. The weather is better in the Third World than it is where I live in New Hampshire. And household help will be much cheaper.”

P. J. O'Rourke (born 1947), American writer and satirist. He lives in Sharon, N.H. (population 352 in the 2010 Census.)

Bad for swimming but perhaps edible

“Algae Bloom” (acrylic pouring on canvas), by Sandrine Colson, in her joint show with George Shaw, “Environmental Effects,’’ at Atlantic Works Gallery, Boston. Ms. Colson, a native of France, lives and works in Boston.

Judith Graham: With the arrival of Aduhelm, what is 'mild cognitive impairment'?

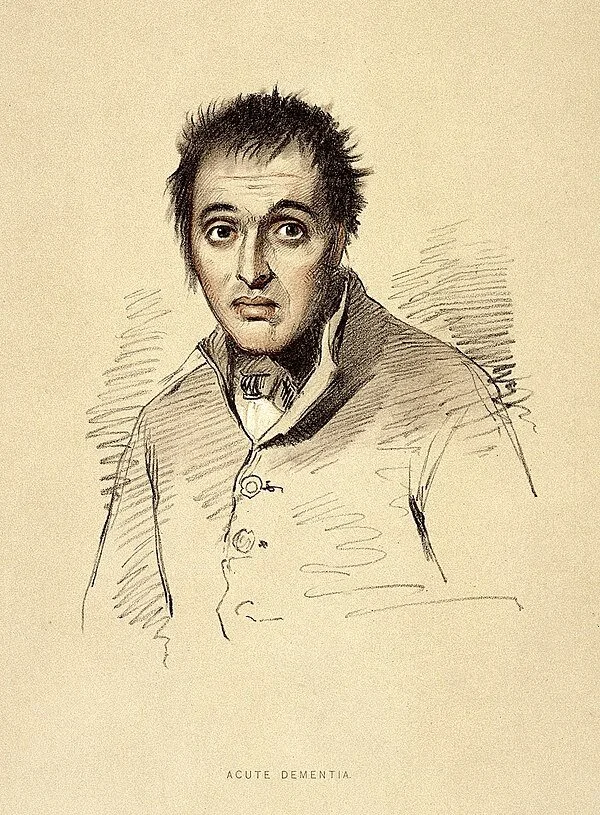

19th Century drawing of man with dementia

The approval of a controversial new drug for Alzheimer’s disease, Aduhelm, made by Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen, is shining a spotlight on mild cognitive impairment — problems with memory, attention, language or other cognitive tasks that exceed changes expected with normal aging.

(Kendall Square in Cambridge, Biogen’s neighborhood, has become arguably the bio-tech center of the world.)

After initially indicating that it could be prescribed to anyone with dementia, the Food and Drug Administration now specifies that the prescription drug be given only to individuals with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage Alzheimer’s, the groups in which the medication was studied.

Yet this narrower recommendation raises questions. What does a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment mean? Is Aduhelm appropriate for all people with mild cognitive impairment, or only some? And who should decide which patients qualify for treatment: dementia specialists or primary-care physicians?

Controversy surrounds Aduhelm because its effectiveness hasn’t been proved, its cost is high (an estimated $56,000 a year, not including expenses for imaging and monthly infusions), and its potential side-effects are significant (41 percent of patients in the drug’s clinical trials experienced brain swelling and bleeding).

Furthermore, an FDA advisory committee strongly recommended against Aduhelm’s approval, and Congress is investigating the process leading to the FDA’s decision. Medicare is studying whether it should cover the medication, and the Department of Veterans Affairs has declined to do so under most circumstances.

Clinical trials for Aduhelm excluded people over age 85; those taking blood thinners; those who had experienced a stroke; and those with cardiovascular disease or impaired kidney or liver function, among other conditions. If those criteria were broadly applied, 85 percent of people with mild cognitive impairment would not qualify to take the medication, according to a new research letter in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Given these considerations, carefully selecting patients with mild cognitive impairment who might respond to Aduhelm is “becoming a priority,” said Dr. Kenneth Langa, a professor of medicine, health management and policy at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Ronald Petersen, who directs the Mayo Clinic’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, said, “One of the biggest issues we’re dealing with since Aduhelm’s approval is, ‘Are appropriate patients going to be given this drug?’”

Here’s what people should know about mild cognitive impairment based on a review of research studies and conversations with leading experts:

Basics. Mild cognitive impairment is often referred to as a borderline state between normal cognition and dementia. But this can be misleading. Although a significant number of people with mild cognitive impairment eventually develop dementia — usually Alzheimer’s disease — many do not.

Cognitive symptoms — for instance, difficulties with short-term memory or planning — are often subtle but they persist and represent a decline from previous functioning. Yet a person with the condition may still be working or driving and appear entirely normal. By definition, mild cognitive impairment leaves intact a person’s ability to perform daily activities independently.

According to an American Academy of Neurology review of dozens of stuies, published in 2018, mild cognitive impairment affects nearly 7 percent of people ages 60 to 64, 10 percent of those 70 to 74 and 25 percent of 80-to-84-year-olds.

Causes. Mild cognitive impairment can be caused by biological processes (the accumulation of amyloid beta and tau proteins and changes in the brain’s structure) linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Between 40 percent and 60 percent of people with mild cognitive impairment have evidence of Alzheimer’s-related brain pathology, according to a 2019 review.

But cognitive symptoms can also be caused by other factors, including small strokes; poorly managed conditions, such as diabetes, depression and sleep apnea; responses to medications; thyroid disease; and unrecognized hearing loss. When these issues are treated, normal cognition may be restored or further decline forestalled.

Subtypes. During the past decade, experts have identified four subtypes of mild cognitive impairment. Each subtype appears to carry a different risk of progressing to Alzheimer’s disease, but precise estimates haven’t been established.

People with memory problems and multiple medical issues who are found to have changes in their brain through imaging tests are thought to be at greatest risk. “If biomarker tests converge and show abnormalities in amyloid, tau and neuro-degeneration, you can be pretty certain a person with MCI has the beginnings of Alzheimer’s in their brain and that disease will continue to evolve,” said Dr. Howard Chertkow, chairperson for cognitive neurology and innovation at Baycrest, an academic health-sciences center in Toronto that specializes in care for older adults.

Diagnosis. Usually, this process begins when older adults tell their doctors that “something isn’t right with my memory or my thinking” — a so-called subjective cognitive complaint. Short cognitive tests can confirm whether objective evidence of impairment exists. Other tests can determine whether a person is still able to perform daily activities successfully.

More sophisticated neuropsychological tests can be helpful if there is uncertainty about findings or a need to better assess the extent of impairment. But “there is a shortage of physicians with expertise in dementia — neurologists, geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists” — who can undertake comprehensive evaluations, said Kathryn Phillips, director of health services research and health economics at the University of California-San Francisco School of Pharmacy.

The most important step is taking a careful medical history that documents whether a decline in functioning from an individual’s baseline has occurred and investigating possible causes such as sleep patterns, mental health concerns and inadequate management of chronic conditions that need attention.

Mild cognitive impairment “isn’t necessarily straightforward to recognize, because people’s thinking and memory changes over time [with advancing age] and the question becomes ‘Is this something more than that?’” said Dr. Zoe Arvanitakis, a neurologist and director of Rush University’s Rush Memory Clinic, in Chicago.

More than one set of tests is needed to rule out the possibility that someone performed poorly because they were nervous or sleep-deprived or had a bad day. “Administering tests to people over time can do a pretty good job of identifying who’s actually declining and who’s not,” Langa said.

Progression. Mild cognitive impairment doesn’t always progress to dementia, nor does it usually do so quickly. But this isn’t well understood. And estimates of progression vary, based on whether patients are seen in specialty dementia clinics or in community medical clinics and how long patients are followed.

A review of 41 studies found that 5 percent of patients treated in community settings each year went on to develop dementia. For those seen in dementia clinics — typically, patients with more serious symptoms — the rate was 10 percent. The American Academy of Neurology’s review found that after two years 15 percent of patients were observed to have dementia.

Progression to dementia isn’t the only path that people follow. A sizable portion of patients with mild cognitive impairment — from 14 percent to 38 percent — are discovered to have normal cognition upon further testing. Another portion remains stable over time. (In both cases, this may be because underlying risk factors — poor sleep, for instance, or poorly controlled diabetes or thyroid disease — have been addressed.) Still another group of patients fluctuate, sometimes improving and sometimes declining, with periods of stability in between.

“You really need to follow people over time — for up to 10 years — to have an idea of what is going on with them,” said Dr. Oscar Lopez, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh.

Specialists versus generalists. Only people with mild cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer’s should be considered for treatment with Aduhelm, experts agreed. “The question you want to ask your doctor is, ‘Do I have MCI [mild cognitive impairment] due to Alzheimer’s disease?’” Chertkow said.

Because this medication targets amyloid, a sticky protein that is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s, confirmation of amyloid accumulation through a PET scan or spinal tap should be a prerequisite. But the presence of amyloid isn’t determinative: One-third of older adults with normal cognition have been found to have amyloid deposits in their brains.

Because of these complexities, “I think, for the early rollout of a complex drug like this, treatment should be overseen by specialists, at least initially,” said Petersen of the Mayo Clinic. Arvanitakis of Rush University agreed. “If someone is really and truly interested in trying this medication, at this point I would recommend it be done under the care of a psychiatrist or neurologist or someone who really specializes in cognition,” she said.

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Judith Graham: khn.navigatingaging@gmail.com, @judith_graham

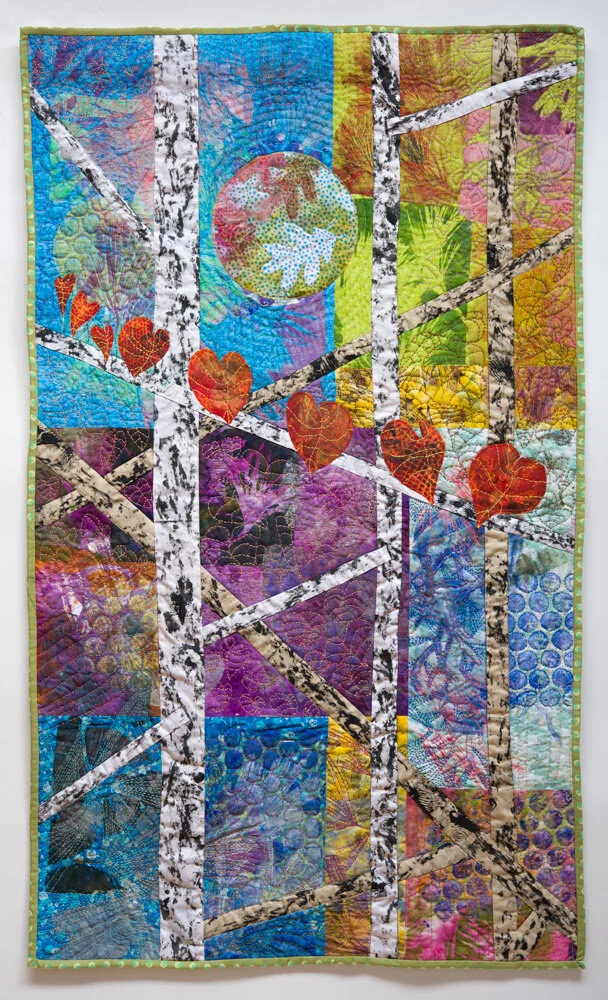

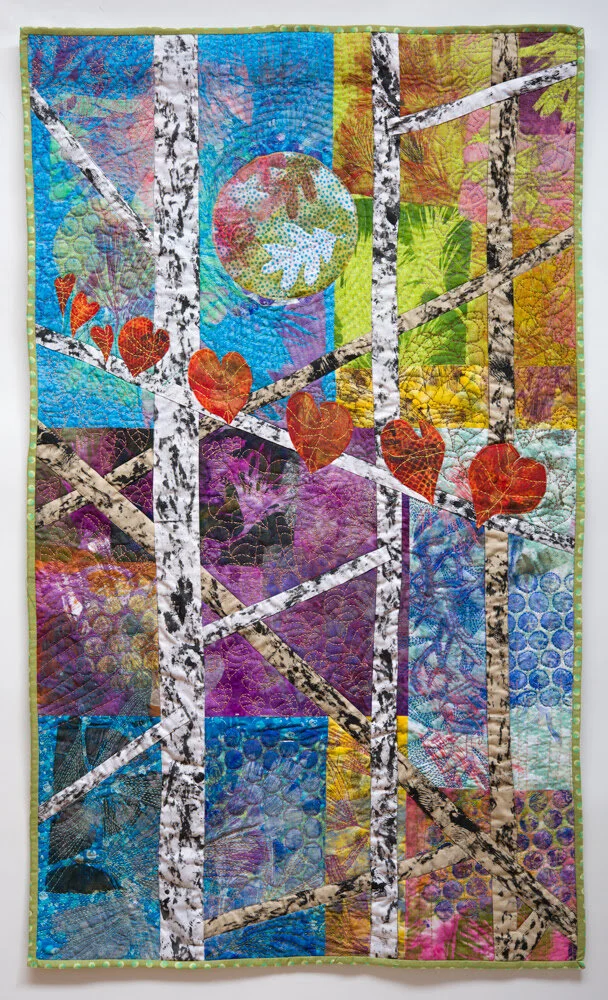

Creative walks through The Fells

“Winter Fire” (mono-printed fabric hand sewn with perle cotton), by Agusta Agustsson, in her show “Forest Bathing,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Oct. 1-Oct 31.

She explains:

"My walks through {The Middlesex} Fells on the edge of my city provide me with inspiration, material resources and spiritual sustenance. These pieces portray those moments seen from the corner of my eye, sensations rather than clear visions. It might be a branch of beech leaves seemingly afire in a sudden bolt of sunshine or the piney aroma as my feet tread my path. On my walk shapes and textures of common plants will catch my eye and come back to my studio to print fabric for my next piece. As I walk through well-worn paths I see the earth is capable of great renewal. I hope we as a species will allow it to happen.’’

A stone foot bridge crossing an 18th Century dam in the Spot Pond Archeological District of the Middlesex Fells Reservation in Stoneham, Mass.

— Photo by User:Magicpiano

The Middlesex Fells Reservation, often called simply as The Fells, is a public recreation area covering more than 2,200 acres in Malden, Medford, Melrose, Stoneham and Winchester, Mass. The state park surrounds two inactive reservoirs, Spot Pond and the Fells Reservoir, and the three active reservoirs (North, Middle, and South) supplying Winchester.

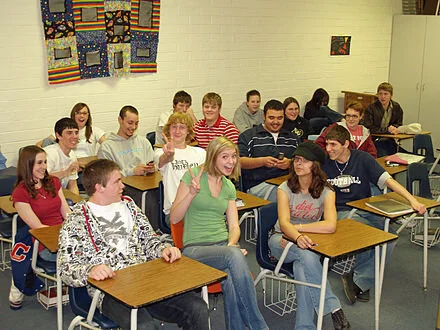

Don Pesci: Four things wrong with public education

The Gull School, also known as the Gott School or District Six, is a one-room schoolhouse that once served the southeast section of Hebron, Conn. Built in 1790, it burned down and was rebuilt in 1816, continuing to serve as a school until it closed in 1919. It reopened in 1929 and then continued as a school until 1935. It’s now a sort of museum.

The diamond shape of Hebron’s town seal has its origins in the diamond figure brand, required on all horses kept in Hebron by a May 1710 act of the Colonial Assembly.

VERNON, Conn.

Teachers and ex-teachers – more numerous these days – will be familiar with the old saw: “Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach; and those who can’t teach, teach teachers.”

This is a slur on a noble profession, recognized as such by attentive students and many teachers, retired or otherwise.

There is much in the postmodern world that militates against teaching, hence the increase in dropouts in the profession, and we all should recognize that teaching is at its core both a profession and a professing of some sort of doctrine or truth. Socrates and Christ, for example, were teachers.

Pedagogy has never been everyone’s cup of tea. In postmodern America, just as everyone is either selling something or buying something – a product, a service, an idea, etc. -- so, in the teaching profession, teachers offer to their students the benefits of their minds and experiences. Personalized knowledge that comes from a live mouth to a listening ear is the best kind of teaching. It sticks in a way that, say, virtual teaching does not. The sharp dip in student performance during an extended virtual teaching bout underscores the importance of personalized teaching.

Now then, if a teacher is charged with teaching students how to think, what is the mission of those who teach teachers?

The answer is obvious: The mission of those who teach teachers is to teach their charges how to teach.

Paulo Freire, the godfather of critical pedagogy, is the author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, a highly influential book – in fact, the third most cited book in the social sciences -- widely used in teacher training and certification courses. The premise of the book is that teaching itself, the transmittal of knowledge from teacher to student, often is a form of oppression, hence the title of the book.

Freire was a Brazilian pedagogue and progressive Marxist philosopher, a target of the 1964 Brazilian military coup d'état that had imprisoned him as a traitor for 70 days. Following the enthusiastic international reception of his widely read and highly influential book, Freire was offered a visiting professorship at Harvard University in 1969.

At least two notable American terrorists -- Bernardine Dohrn, a leader of the radical Weather Underground, now a retired law professor, and her husband, Bill Ayers, retired Distinguished Professor of Education and Senior University Scholar in the College of Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago – intellectually sat at the knees of Freire.

The Weather Underground, a radical, militant organization claimed responsibility for bombings at the U.S. Capitol, the Pentagon, and several police stations in New York, as well as a Greenwich Village townhouse explosion that killed three of its own members. Fortunately, U.S. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi was not in attendance during the bombings. Both Dohrn and Ayers later shucked off their terrorist ways.

But Freire’s ways and doctrines are with us still. Oppression, big on college campus in the late 60’s, has trickled down to the lower grades.

Not only do teachers oppress, there is something in the nature of knowledge itself that is oppressive. Some texts oppress, and it would be far better if such oppressive texts were to be replaced not by objectively true historical narratives but by imaginative story telling that corrects the various oppressions of history -- enter critical thinking.

The purpose of critical thinking for Freire, a thoroughgoing Marxist, is not simply to reproduce accurately the past and understand the present; it is to alter both by entering into a critical dialogue with history for the purpose of imagining a future – prospectively less oppressive – that will transform both the past and the future. The traditional education system, Freire taught, was designed to crank out thoughtless workers in order to perpetuate the capitalist system which continually oppresses the working class

Karl Marx put the idea more lucidly this way: “Hitherto,” Marx said, “philosophers have interpreted the world, the point however is to change it.” The new pedagogy hopes to change the world by changing young minds and abolishing objectively real history in favor of literary if not fictional personal narratives. That is also the primary goal of Critical Race Theory, a destructive pedagogy much talked about these days but little understood.

Four things are wrong with education here in Connecticut and elsewhere in the nation: 1) best education practices should be taken from the field, not from education professors doped up on Freire and false pedagogical amelioratives; 2) subject matter in the various courses should predominate over esoteric psychological and pedagogical theories; 3) the teaching profession has become over-credentialed and should admit to high schools professionals in various fields and occupations whose efforts have not yet been turned under by education courses, and 4) political power and decision making should revert from distant politicians to the municipalities where education decision making belongs.

Kids matter, but so do excellent teachers. Some way must be found to retain at every level of education the best teachers and at the same time to easily eject the worst. The old saw about the rotten apple spoiling the bunch is often repeated because it is often true.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Invasive (like us) and relentless

Crying for supper in suburbia

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s lots of talk and worry about coyotes in and around New England urban areas. We’d better get used to them. They’re smart and opportunistic. Their increasing numbers show how some wild animals can and must adapt as people take over more and more of the Earth’s space.

You might call coyotes invasive species in these parts, but then so are we, if you go back far enough. And maybe, like dogs, their canid cousins, they too will ultimately be domesticated. Maybe even raccoons, who have also become suburbanites and even urbanites, will be domesticated. They’re quite intelligent creatures. (Even moose, who aren’t smart, are wandering into some New England cities, such as Worcester.)

But keep your house cats inside. Coyotes will kill and eat them. But then, cats kill many, many songbirds so…

— Photo by Rhododendrites

Meanwhile, gird yourself for the Spotted Lanternfly, an invasive species moving into southern New England, aided and abetted by global warming. The Pennsylvania Dept. of Agriculture reports:

“The spotted lanternfly causes serious damage including oozing sap, wilting, leaf curling and dieback in trees, vines, crops and many other types of plants. In addition to plant damage, when spotted lanternflies feed, they excrete a sugary substance, called honeydew, that encourages the growth of black sooty mold. This mold is harmless to people; however, it causes damage to plants.’’

If you see any of these execute as many as you can. But happily, it will take a while for Burmese pythons to make their way up here from Florida.

Chris Powell: Since epidemic is permanent, emergency powers should end; housing price crisis

“The Plague of Athens” (c. 1652–1654), by Michiel Sweerts, illustrating the devastating epidemic that struck Athens in 430 B.C., as described by the historian Thucydides

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont seems inclined to ask the state General Assembly to extend his emergency powers again to deal with the virus epidemic when they expire at the end of the month. The governor’s request likely would be for another 90 days. The legislature should decline.

For starters, while the epidemic continues and is expected to continue indefinitely, there no longer is an emergency.

An emergency is something that is sudden, unexpected, and urgent. But the governor’s emergency powers have been in effect for more than18 months, the epidemic has become a way of life for everyone, and nothing about it is sudden, unexpected, and urgent.

For months Connecticut has been dealing well with the epidemic, and the governor can take much credit for that. But he will not deserve credit for changing the definition of “emergency.” When something becomes permanent, it’s not an emergency anymore.

At the beginning of the epidemic state legislators were only too happy to abdicate to the governor and run home and hide under their beds even as their constituents trudged on, trying to keep working as best they could, when they were allowed to work at all.

Now even legislators have discovered they can adapt with Internet meetings and “social distancing” in the workplace. The General Assembly held a relatively normal legislative session this year.

So there’s no reason for the legislature to keep deferring all epidemic-related policy decisions to the governor. The legislature is fully capable of reviewing his emergency declarations, enacting some into statute and nullifying others, and fully capable of approving or rejecting his additional proposals and involving the public through hearings in person or on the internet.

Just as important as the procedure for resuming normal government is the substance. The governor’s emergency rules long have touched nearly every aspect of life — business, commerce, schools, restaurants and more. It is hardly possible to leave one’s home for even a half-hour without having to comply with some executive order that was not in place a year and a half ago, an order issued directly by the governor or by municipal officials to whom he has delegated authority.

Democracy requires the people’s assent to such rules through their elected representatives. Otherwise Connecticut has reverted to monarchy. While it has been a benevolent monarchy so far, even that risks eroding the state’s habit of democracy, which was already fragile enough before the epidemic.

If a real emergency descends on the state after Sept. 30 — an asteroid strike, a solar flare, a plague of frogs or locusts, or anything else Connecticut hasn’t been handling for 18 months already — the governor can always ask legislative leaders to abdicate to him again. Until then, ordinary democracy should resume, and legislators who are unwilling to do the jobs they were elected to do should resign and let the people choose replacements.

Picture by IDuke

Anyone in Connecticut who owns his home may be rejoicing over the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s report two weeks ago that house prices in the state have risen 20 percent in the last 12 months. But actually this is a disaster, since housing is, like food, a necessity of life, and homeownership is the primary mechanism of giving people a stake in society generally and their community particularly and of building generational wealth.

Of course, the problem is not peculiar to Connecticut. Nationally house prices rose 17% in the last year, the main reasons being the de-urbanization stoked by the virus epidemic, inflation, and interest rates that have been pushed below the inflation rate by the Federal Reserve, which is pumping up asset prices to protect the wealthy while the poor choke.

But housing prices are Connecticut’s problem all the same, and rising prices for houses are pulling up rental housing prices as well, squeezing the poor. Higher prices for necessities reduce discretionary income and thereby risk weakening the economy.

The solution is for government to enable the market to increase supply — to loosen land-use restrictions and allow conversion of vacant commercial properties to housing. But will people sitting on another 20% in unrealized capital gains cooperate politically?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Too foliage-oriented?

“Nope, Not This” (acrylic on canvas), by Rupert, Vt.-based Jane Davies, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

Countryside in eastern Rupert.

Rupert is the filming location for the syndicated PBS cooking show Cook's Country. The white country house, known as Carver House, has been used as the show’s set. Christopher Kimball, former executive producer and host of Cook's Country, has a house nearby.

David Warsh: Looking at a ‘three-pronged approach’ to global warming

Average surface air temperatures from 2011 to 2020 compared to the 1951-1980 average

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The most memorable theater scene I’ve ever witnessed was performed one summer evening long ago in a courtyard at the University of Chicago. The play was Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, a complicated work from the 1920s about the relationship between authors, the stories they tell, and the audiences they seek.

At one point, a company of actors, having been interrupted in their rehearsal by a family of six seeking a playwright to tell their story, are bickering furiously with their interrupters when, at the opposite end of courtyard, two key members of the family had slipped away, to be suddenly illuminated by a spotlight as they stood beneath a tree to make a telling point: their story was as important as the play – maybe more. The act ended and the lights came up for intermission.

That was the technique known as up-staging with a vengeance, an abrupt diversion of attention from one focal point to another.

I remembered the experience after reading Three Prongs for Prudent Climate Policy, by Joseph Aldy and Richard Zeckhauser, both of the Harvard Kennedy School, a sharply critical appraisal of the prevailing consensus on the prospects for controlling climate change. Delivered originally as Zeckhauser’s keynote address to the Southern Economic Association in 2019, you can read it here for free at Resources for the Future. Its thirty pages are not easy reading, but they are formidably clear-headed, and I doubt that you can find a better roundup of the situation that the leaders are discussing blah-blah-blah next month at the U.N.’s Climate Change Conference in Glasgow.

The possibility of greenhouse warming was broached 125 years ago by the Swedish physical chemist Svante Arrhenius. The specific effect was discovered by Roger Revelle in 1957, and the growing problem brought into sharp focus in the U.S. by climate scientist James Hansen in Senate testimony in 1988. It has taken thirty years to reach a broad global consensus about the first of Aldy and Zeckhauser’s three prongs.

“For three decades, advocates for climate change policy have simultaneously emphasized the urgency of taking ambitious actions to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and provided false reassurances of the feasibility of doing so. The policy prescription has relied almost exclusively on a single approach: reduce emissions of carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other GHGs. Since 1990, global CO₂ emissions have increased 60 percent, atmospheric CO₂ concentrations have raced past 400 parts per million, and temperatures increased at an accelerating rate. The one-prong strategy has not worked.’’

A second prong, adaptation, has been added in to most menus in recent years: everything from design changes (moving electric installations to roofs instead of basements) to seawalls, marsh expansions, and resettlement of populations. Adaptations are expensive. A six-mile long sea barrier with storm surge gates might protect New York City from climate change, but would take 25 years to build.

A third prong of climate policy ordinarily receives little attention. This is amelioration, or “the ‘G’-word,” as the chair of British Royal Society report dubbed it in 2009, meaning the broad topic of geo-engineering. For a dozen years, it was thought possible that fertilizing the southern oceans might grow more plankton, absorb more atmospheric carbon, and feed more fish. Experiments were not encouraging. The technique considered most promising today is solar-radiation management, meaning creating atmospheric sun-screens for the planet. The third prong is by far the last expensive of the three. It is also the most alarming.

Ever since “the year without a summer” of 1816, it has been known that volcanic eruptions, spewing sulfur particles into the atmosphere, produce worldwide net cooling effects. Climate scientists now believe that airplanes could achieve the same effect by spraying chemical aerosols at high altitudes into the atmosphere. The trouble is that very little is known with any certainty about the feasibility of such measures, much less their ecological effects on life below.

Many environmentalists fear that the very act of public discussion of solar- radiation management will further bad behavior – create “moral hazard” in the language of economists. Glib talk by enthusiasts of economic growth about cheap and easy redress of climate problems will diminish the imperative to reduce emissions of greenhouse governance, some say. Others think that sulfur in the air above would accelerate acidification in the oceans below. Still others doubt that global governance could be achieved, since such measures would not offset climate change equally in all regions, Rogue nations might undertake projects that they hoped would have purely local effects.

Aldy and Zeckhauser argue that bad behavior may in fact be flowing in the opposite direction. Climate change is an emotional issue; circumspection with respect to solar-radiation management is the usual stance; opposition to research is often fierce. As a result, very little has been performed. One of the first outdoor experiments – a dry run – was shut down earlier this year.

In his 2018 Nobel lecture, William Nordhaus, of Yale University, saw the problem somewhat differently.

“To me, geo-engineering resembles what doctors call ‘salvage therapy’– a potentially dangerous treatment to be used when all else fails. Doctors prescribe salvage therapy for people who are very ill and when less dangerous treatments are not available. No responsible doctor would prescribe salvage therapy for a patient who has just been diagnosed with the early stage of a treatable illness. Similarly, no responsible country should undertake geo-engineering as the first line of defense against global warming.’’

After a while, it seemed to me that the debate over global warming does indeed bear more than a little resemblance to what goes on in Pirandello’s play. Three possible policy avenues exist. The first is talked about constantly: the second enters the conversation more frequently than before. The third is all but excluded from mainstream discussion.

It’s not so much about what stage of a treatable illness you think we’re in. Public opinion around the world will determine that, as time goes by. It’s about whether the question of desperate measures should be systematically explored at all. The three-pronged approach is a policy in search of an author.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Chuck Collins: The simplest, most effective and most popular way to fund infrastructure and jobs bill (Copy)

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

As lawmakers scramble to finalize a historic jobs and infrastructure package, huge fights are underway to figure out how to fund it.

The simplest, most effective, and most popular way is to tax the extremely wealthy, like the billionaires who’ve seen their collective wealth grow by $1.8 trillion during the pandemic. Unfortunately, lawmakers have missed several opportunities to do this.

For example, the House Ways and Means Committee has failed to take obvious steps like taxing income from stocks at the same rate as income from work, or closing the loopholes billionaires use to avoid the federal estate tax.

On the other hand, the Committee has also suggested some powerful inequality-fighting reforms that should be in the final legislation. One of these promising proposals is a “Millionaires Surtax.”

The idea is simple: Any income that multimillionaires earn over a certain amount would face a modest additional tax.

The Millionaires Surtax was originally introduced in 2019 and reintroduced in 2021 by Maryland Sen. Chris Van Hollen and Virginia Rep. Don Beyer. That bill would institute a 10 percent surtax on the incomes of couples making $2 million or more (the top 0.2 percent). The Tax Policy Center estimated this would raise $635 billion over 10 years.

The Americans for Tax Fairness coalition has coordinated a national campaign that has now put the concept at the center of the federal budget negotiations.

The recently released House Ways and Means plan differs slightly from that original proposal. It would impose a 3 percent surtax on the incomes of ultra-wealthy households making $5 million or more per year, raising an estimated $127 billion over 10 years. It also applies to incomes from investments, including trusts.

That’s a smaller haul to be sure, but worth building on.

Of course, the Holy Grail of tax reform would be a total elimination of the preferential treatment of capital gains, taxing income from wealth at the same rates as income from wages. Short of that, a surtax on the incomes of ultra-millionaires is an important foot in the door toward equalizing the treatment of capital and wage income.

The Millionaires Surtax is easy to understand, simple to apply, and effective — because it covers all kinds of income, making it difficult for the wealthy to avoid. It’s laser-focused on the super-rich. If you’re not a multi-millionaire, you won’t pay one extra dime.

The surtax is overwhelmingly popular.

According to a poll by Hart Research Associates, 73 percent of voters support the idea, including 76 percent of independents and moderates. Even a majority of Trump voters (57 percent) and Republicans (53 percent) favor the policy. The Millionaires Surtax legislation has been endorsed by a diverse range of 72 national organizations.

In the coming weeks, Congress will debate the size of the Build Back Better plan and how to pay for it. The Millionaires Surtax should remain part of that mix and could even be expanded by raising the rate from 3 percent to 10 percent — and lowering the income threshold to $2 million.

While the Millionaires Surtax does not address the colossal inequalities of wealth, it focuses on taxing income that largely flows from wealth. See more about the Millionaires Surtax at the campaign website created by the Americans for Tax Fairness: www.surtax.org.

Chuck Collins, based in Boston, directs the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies.

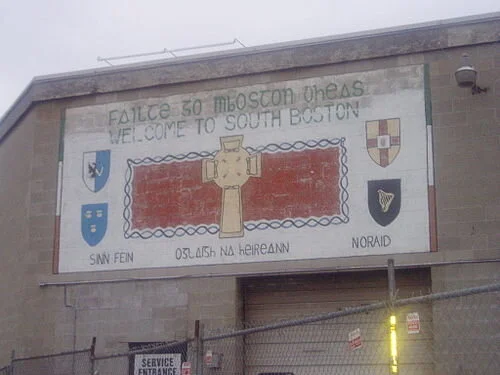

'Without contempt'

Mural in South Boston saying "Welcome to South Boston" in English and "Fáilte go mBoston dheas" in Irish. Also shown is a Celtic cross, the coats of arms of the provinces of Ireland and the words "Sinn Féin" "Irish Republican Army" and "NORAID." This building was torn down along with the building to make way for housing.

“The sea is dark and choppy.

So far out on the vellum streets

only taxis.

Three nuns sit on the stone bench

and study the storm without contempt….’’

— From “South Boston Morning,’’ by Norman Dubie

The Moakley Courthouse on the South Boston waterfront

‘Repeated denials’

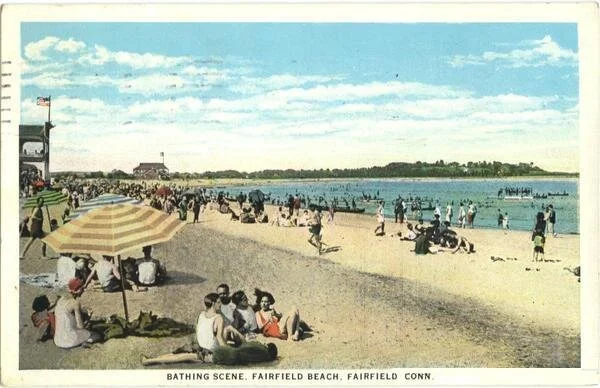

“All the Boys (Profile 2)” (archival pigment print on gesso board), in the show “Carrie Mae Weems: The Usual Suspects,’’ at the Fairfield University Art Museum, Fairfield, Conn., through Dec. 18

The show is a photography and video exhibition focusing on “the humanity denied in recent killings of Black men, women, and children by police.” Through the work, the museum says, Weems invites viewers to reflect on what has happened time and time again in the United States of America: “Weems directs our attention toward the repeated pattern of judicial inaction—the repeated denials and the repeated lack of acknowledgement.”

1932 colorized posrtcard

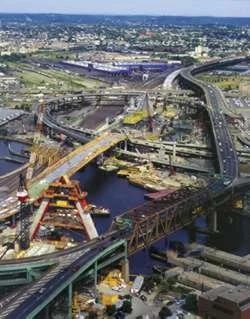

James T. Brett: Infrastructure bill would be a boon for New England

Work underway during “The Big Dig,’’ in Boston (1991-2106), New England’s most dramatic local infrastructure project so far.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

With billions of dollars of federal relief authorized over the past 18 months, and more and more Americans receiving vaccinations each day, our economy is gradually inching closer to recovery. However, there is more left to do. The New England Council believes that passing a robust infrastructure package will help meet numerous and long-standing unmet demands, and will help our region’s businesses remain competitive and allow our residents to thrive.

As New Englanders, we know all too well the infrastructure challenges that our region faces. Too many of our bridges are structurally deficient and yearly increases in the number of vehicles and drivers have put more stress on our roadways. A growing number of residents across our region are looking to transit to provide a safe, affordable and reliable means of transportation. Besides the need to meet new requirements for a growing region, our aging water systems – some approaching or surpassing a century old – need attention. And the pandemic has shown that broadband is a critical need for New England to expand telework, telehealth and remote learning options. These and many other needs must be addressed.

Just months ago, a bipartisan group of senators and President Biden agreed upon a bold infrastructure framework This five-year deal would fund so-called “traditional” infrastructure – roads, bridges, rail, transit, ports and airports and water systems. In addition, the deal called for new infrastructure spending which would be allocated towards those traditional infrastructure items along with an expanded list of core infrastructure such as broadband, resiliency, and electric-vehicle infrastructure.

As for financing the new spending, the agreement called for more than a dozen ways to do so, including redirecting unused unemployment insurance payments; re-purposing certain unspent COVID-19 relief funds; extending customs fees; reinstating certain Superfund fees, and selling off telecom spectrum to name a few.

In late July, senators reached a final deal on legislation to enact the bipartisan agreement. Besides baseline funding, some $550 billion in new spending over the next five years was included, representing a compromise backed by members of both parties. The bill included a number of the “pay-fors” from the original agreement as well as new funding sources designed to maximize support among the members of the Senate. The Senate legislation also included other crucial infrastructure priorities for our region, like addressing PFAS contamination.

The hard work of the Senate paid off. On Aug. 10, this legislation – the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act – was adopted by a bipartisan vote of 69 to 30. Every senator from New England voted in favor.

Now, the bill is before the U.S. House of Representatives, and a vote is slated to be held before the end of this month.

Not since the Eisenhower administration has Congress had such an opportunity to advance a package that will so boldly affect infrastructure in a manner that will benefit virtually every individual in New England and across the nation. The New England Council believes that this landmark legislation would have a tremendous impact on our region by addressing many of the challenges we face, while also creating new jobs and spurring economic growth. We are grateful to the Senate for taking quick action on the bill, and we urge the House to follow suit as soon as possible.

James T. Brett is president and chief executive of The New England Council.

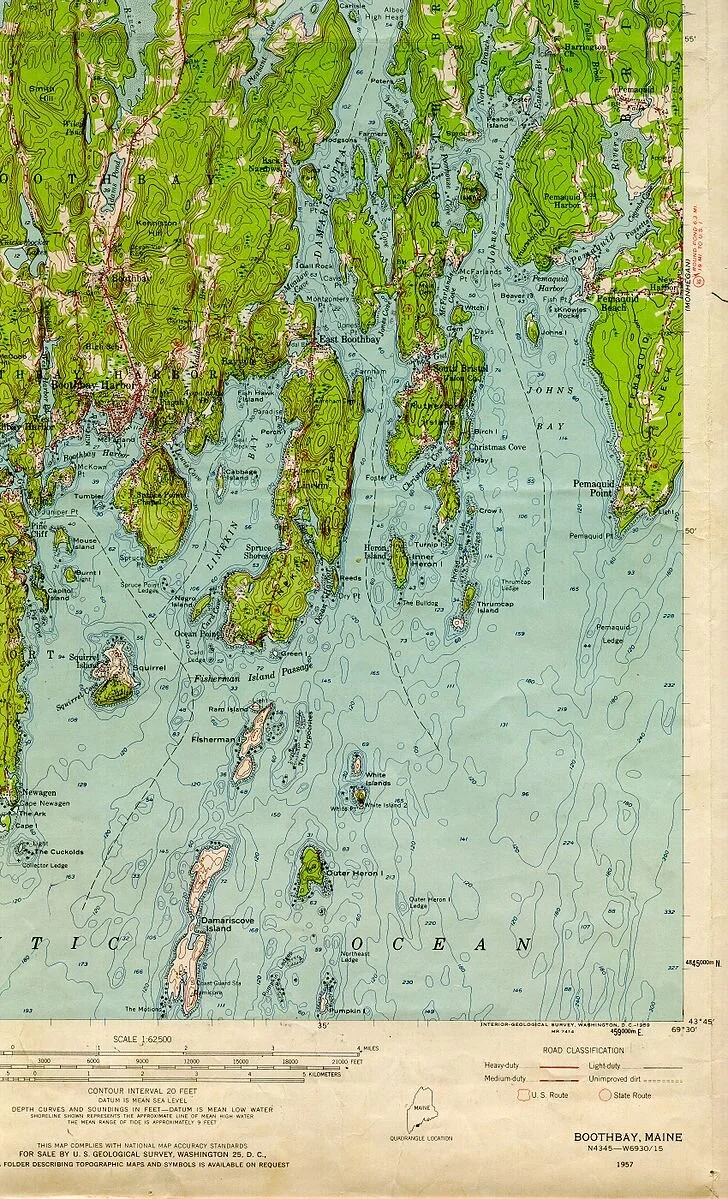

Farming Maine oysters as the coastal environment changes

— Photo by Barbara Scully

https://thelobsterstore.com/

“When I opened Maine Oysters – Stories of Resilience and Innovation, I immediately encountered the color, the beautiful photos, compelling personal stories, accurate history, and the roles of a wide range of people woven together to tell the success story of farmed Maine oysters. It is an astonishing record for the public to enjoy.”

— Dick Clime, co-founder of Dodge Cove Oyster

See:

https://www.maineoysterbook.com/gallery-1

and:

https://www.maineoysterbook.com/

‘No light like it’

Cheery fall foliage brightens the cliffs of Buttermilk Falls in Gulf Hagas, Maine. Gulf Hagas is sometimes called “The Grand Canyon of Maine’’.

— Photo by Andythrasher

“She ran into the early-October afternoon. The light came at a low slant through the oaks across the street, gold and green, and how she loved that light. There was no light in the world like you saw in New England in early fall.”

— Joe Hill (born 1972, in Hermon, Maine), American novelist and a son of famed Maine writer Stephen King

xxx

"And there, next to me, as the east wind blows in early fall, a season open to great migrations, are those lives, threading the air and waters of the sea, that come out of an incomparable darkness, which is also my own."

— John Hay (1915-2011), in The Way to the Salt Marsh: A John Hay Reader. He was a celebrated nature writer who lived much of his life in Brewster, Mass. (on Cape Cod) and Bremen, Maine, which is on Muscongus Bay.

The southwest tip of Muscongus Bay at the Pemaquid Point Lighthouse.

In Brewster: Linnell Landing Beach, on Cape Cod Bay.

'Ambiguities of abstraction'

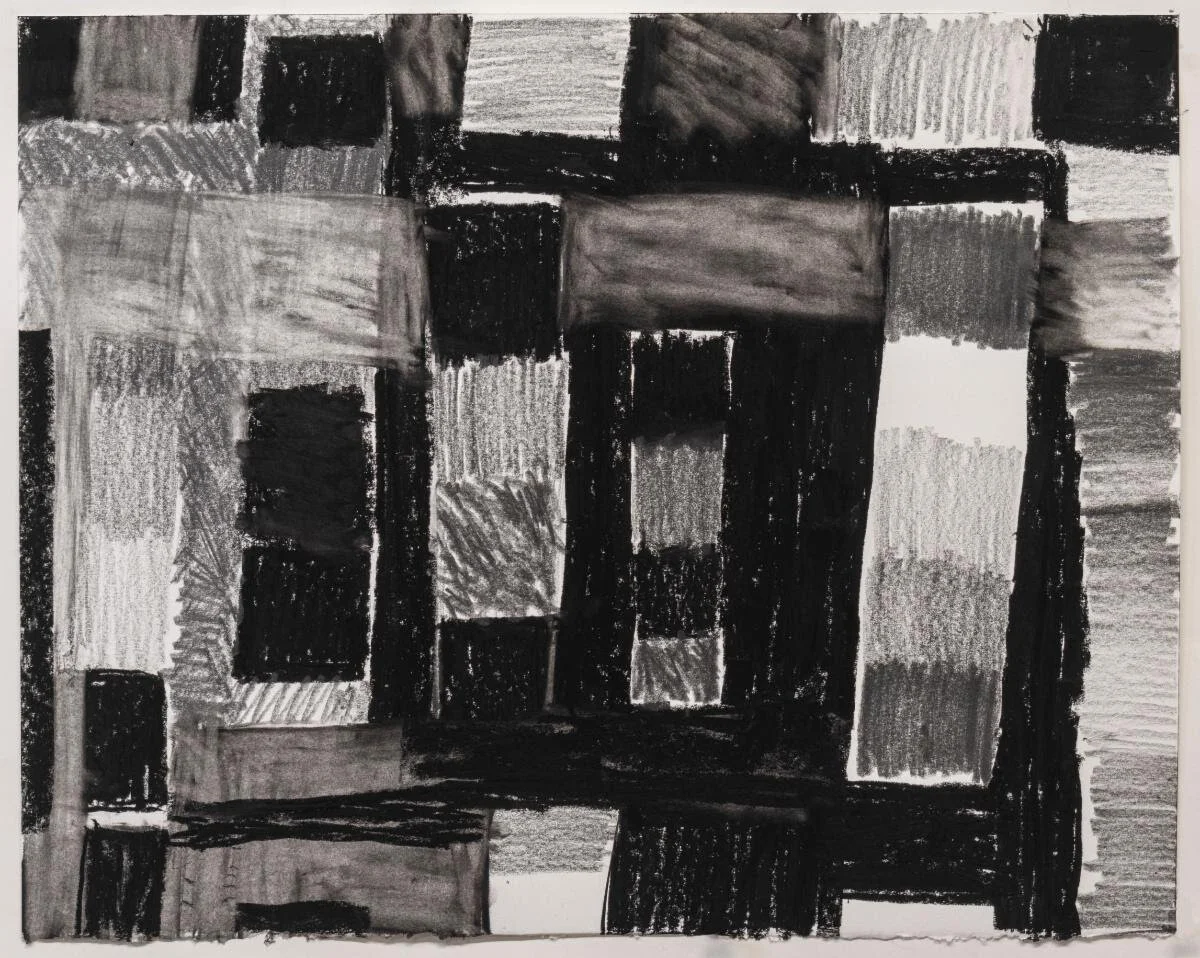

“Untitled Drawing” ( charcoal and graphite on paper), by Brian Littlefield, in his show “Smaller,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Nov. 3-28.“

Untitled Drawing” ( charcoal and graphite on paper), by Brian Littlefield, in his show “Smaller,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Nov. 3-28.

The gallery says:

“Brian Littlefield devotes his practice to multifaceted ambiguities of abstraction. In his first solo exhibition at Kingston Gallery, ‘Smaller’ seeks to foster a direct approach to drawing, using straightforward materials such as charcoal and graphite. His grayscale works suggest patchwork landscapes, which are born more from nature than from mathematical abstraction. Littlefield’s improvisational work can shift between form and space by compressing internal and external locations, recurring interests, and ruminating thoughts.’’

Llwelleyn King: Good reasons to venerate the gig economy

Professional dog walker

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Napoleon didn’t deride the English as “a nation of shopkeepers,” although that phrase is commonly attributed to him. In fact, it was Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac, a French revolutionary who used it when attacking the achievements of British Prime Minister William Pitt, the Younger.

I think that Napoleon was too smart not to have realized that a nation of shopkeepers is a strong nation, and that if the English of the time were indeed a nation of shopkeepers, they would constitute a more formidable enemy.

A nation of shopkeepers, to my mind, is an ideal: self-motivated people who know the value of work, money and enterprise; and who are almost by definition individualists. So, I regret the constant threats to small business coming from chains, economies of scale, high rents and some social stigma.

But mostly I regret that in our education system, self-employment isn’t celebrated and venerated as being equivalent to work at larger enterprises. We define too many by where they work, not by what they do.

I have always believed that one should aspire to work for oneself, to eschew the temptations of the big, enveloping corporation and to strike out with whatever skills one has to test them in the market and to have the customer, not the boss, tell you what to do.

Our education system produces people tailored to be employed, not self-employed.

But things are changing. The gig economy was well underway before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and now it is roaring. Many employees found that the servitude of conventional employment wasn’t for them.

The gig world differs from the small business world that I have described in that it is small business refined to its absolute core: a one-person business, true self-employment.

There are many advantages in self-employment for society and for the larger business world. Hiring a self-employed contractor is easier for a company, not having to create a staff position and pay all the costs that go with it. Laying off a contractor isn’t as traumatic. The worker is more respected, and is asked to do things not commanded. The system gains efficiency.

But if employers come to see the gig economy as just cheap, dispensable labor, then the gig economy has failed.

The gig worker shouldn’t expect security but should be treated in a business-to-business environment. He or she needs to know how to drive a bargain and to have the moral courage to ask for a contract that is fair and recognizes the value that is intrinsic in the gig relationship.

I am a fan of Lyft and Uber. They offer self-employment to anyone with a driver’s license and a car — and the companies will even get you into a car. But the bargain is one-sided. The driver has the freedom to work what hours he or she chooses but not to negotiate the terms of their engagement. That is decided by a computer in San Francisco.

This gig worker can’t hope to hire other drivers and start a small business: It doesn’t pass the gig contract concept. I have talked to many ride-share drivers. They revel in the freedom but not the income.

Gig workers can be, well, anything from a plumber to a computer programmer, from a dog walker to an actuary.

But for the free new world of gig working to become part of our business fabric, the social structure needs to be adjusted by the government to allow for the gig worker to enroll in Social Security and to charge expenses against taxes as would an incorporated business. Jane Doe, who makes a living designing websites, needs to know that she is a business, not just freelancing between jobs.

A friend who has been self-employed for many years told me recently that he was being considered for a big staff job. I told him to be mindful that he will be trading away some dignity and a lot of freedom. It is hard to get into a harness when you have been running free.

I hope we get many more workers running free. Napoleon would have understood.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., and his email is llewellynking1@gmail.com

White House Chronicle

Gird yourself

“First Light” (on on braced panel), by Janis Sanders, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

First Light

20 x 16 in.

oil on braced panel

$1,600

Chris Powell: Appeal on abortion won’t lure Texas firms to Conn.

M ANCHESTER, Conn.

While he tries to be a moderate Democratic governor and indeed is more moderate than his predecessor, Connecticut’s Ned Lamont still feels obliged to make regular obeisance to his party's left wing, which constitutes a majority of the party's activists. So last week the governor posted on his social media channels a minute-long video encouraging businesses in states that are restricting abortion to relocate to Connecticut.

Connecticut, the governor said, is "family-friendly" and its liberal abortion law "respects" women.

The new abortion law in Texas is not just almost prohibitive but bizarre, delegating enforcement to civil lawsuits for damages. But it would not have been enacted if Texas was not full of women whose idea of respect includes protecting what they call the pre-born. The women of Texas are fully capable of getting the law repealed.

In the meantime, Connecticut's pitching businesses in Texas and other states restricting abortion is ridiculous, as is a similar appeal made to Texas businesses the other week by Chicago's economic-development agency, which placed an advertisement in the Dallas Morning News.

The Chicago agency's chief executive, Michael Fassnacht, told Bloomberg News: "We believe that the values of the city you are doing business in matter more than ever before." But of course the "values" of Chicago encompass scores of shootings and dozens of murders almost every weekend, while the "values" of Illinois include the country's worst insolvency.

Connecticut does not have the violent crime of Chicago, nor is Connecticut quite as insolvent as Illinois. Connecticut has advantages of climate, geography and culture. But in friendliness to business, Texas clobbers Connecticut and Illinois, having no corporate- and personal-income taxes while Connecticut and Illinois have both.

The Tax Foundation says the personal-tax burden in Connecticut and Illinois is above 10 percent but is only 7.6 percent in Texas. That is, Connecticut's personal-tax burden is almost a third higher than that of Texas.

Not surprisingly, Texas long has been gaining population relative to the rest of the country while Connecticut has been losing.

With such a differential in taxes, even Texas businesses opposed to the new abortion law might save so much money by staying put and not relocating to Connecticut that they could afford to pay for their employees to come to Connecticut for abortions every year.

No amount of the governor's pandering to his party's left wing will make Connecticut's high taxes "family-friendly."

Nevertheless, higher taxes well may be on the way for Connecticut, since the governor and Democratic leaders in the General Assembly seem inclined to revive in a special legislative session what they call the Transportation Climate Initiative. The plan would raise wholesale taxes on gasoline so the added burden wouldn't be as visible as the retail tax and would claim that the new revenue would be spent on transportation projects that reduce pollution.

But the state is already rolling in emergency federal money and billions more in federal "infrastructure" appropriations may arrive soon, so Connecticut hardly needs more gas tax money.

Raising gasoline taxes will be most burdensome to the poor and middle class even as inflation is already roaring and eroding their living standards. Further, it would be unusual if any money raised by state government in the name of transportation wasn't diverted.

With its taxes already so high, state government needs mainly to set better priorities.

xxx

Last week Governor Lamont announced with some pleasure that his administration will close another prison, the one in Montville, because the state's prison population is declining so much.

When the announcement was made four people had just been shot in separate incidents in Hartford over the Labor Day weekend, making nine shootings there for the previous week. There had just been four shootings in New Haven as well. The day before the prison announcement a Hartford man, a chronic offender, earned his 14th conviction and was sent back to prison.

The rise in violent crime and the failure to deter repeat offenders could make prison closings seem premature.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Leave him up

William Blackstone in glorious stainless steel in Pawtucket, R.I.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The bookish William Blackstone (1595-1675) (also called Blaxton) was an Anglican minister who might have been the first permanent white resident of what is now Rhode Island, moving down from Boston and settling in today’s Lonsdale section of Cumberland in 1635, the year before Roger Williams founded Providence. The Blackstone River and a bunch of other things around here are named for him.

In the future Cumberland, on the east bank of the river that would bear his name, the reclusive and apparently kindly and tolerant intellectual read, wrote, tended cattle, planted gardens, and cultivated an apple orchard; he came up with the first variety of American apples, the Yellow Sweeting. He called his home "Study Hill," and it was said to have the largest library in the English colonies at the time. Sadly, his library and house were burned down in 1675 during King Philip's War, the very bloody and destructive conflict between Native Americans and English colonists that lasted from 1675 to 1678 and changed the course of American history. Blackstone died in 1675, just before the outbreak of the conflict.

Consider that his friends included the Narragansett tribe chiefs Miantonomi and Canonchet and the Wampanoags’ Massasoit and Metacomet. Metacomet is also known as King Philip (to mark the friendly relations his father, Massasoit, had with the English), whose followers were the ones who destroyed Blackstone’s home.

But now some Narragansetts want a new stainless-steel sculpture of Blackstone at the corner of Roosevelt and Exchange streets in Pawtucket taken down. They’re trying to make him into some sort of symbol of the brutal white takeover of their lands and the vast suffering and death of Native Americans that accompanied the English colonialization of what the English named New England. But Blackstone is a pretty inaccurate example of white aggression!

It’s appropriate that his statue remain up, given his importance to the history of the region. It’s not as if this is a statue of the likes of the cruel slaveowner, and traitor, Robert E. Lee. Such works are best kept in museums. (There are no statues of Hitler in outdoor parks in Germany, despite his historical importance.)

And, yes, you could say that George Washington was a traitor to Britain and he owned slaves. But unlike Lee, he didn’t take up arms against “his country” to ally himself with a “country’’ whose central mission in its rebellion against the United States was the preservation and indeed expansion of slavery. And Washington, whose slaves were freed at his death under his will, also was not considered a cruel slaveowner.

Anyway, why not see if a statue of a Native American chief from Blackstone’s time in Rhode Island could be commissioned to be put up near Blackstone’s? It would be culturally healthy if we had a wider range of historical figures represented by our public statues.

Here’s a nice crisp biography from the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame:

http://www.riheritagehalloffame.org/inductees_detail.cfm?iid=45