Extreme PC on the half shell

Oysters and mussels

The Whaleback Shell Midden, along the Damariscotta River, in Maine, contains the shells from oysters harvested for food dating from 2,200 to 1,000 years ago.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary’’ in GoLocal24.com

Here’s an example of the sort of political correctness/hyper-sensitivity that drives people into the toxic arms of Trump & Co.:

A couple of us are working on a little book about oyster farmers on the Maine Coast. We wanted to get a couple of pictures of middens, piles of shells left by Native Americans. So we asked a University of Maine project for permission to buy rights to use a couple of their photos. At a staffer’s request, we sent that person the only reference in the book to the middens:

"The central story of the Pine Tree State’s oysters begins on the Damariscotta River, which is really mostly an estuary and which for millennia has been a superb source of oysters. The Wabenaki Indians left huge piles (aka 'middens’) of oyster shells, some as high as 30 feet, that can still be seen on the banks of the Damariscotta. It might be the best environment in which to grow oysters on the planet.'

The staffer wouldn’t cooperate, saying that “Unfortunately, there are misconceptions involving Indigenous use of the coast. I work with the tribes here in the State, and they and I are sensitive about how images and information regarding their lifeways are used.’’

This was accompanied by a list of things, with a couple of the staffer’s factual errors, the staffer presumed we didn’t know about Maine but in fact knew well. My project partner is a Mainer, by the way. The all-too-common arrogance found on the Isle of Academia.

This little tiff also reminded me of the intensely bureaucratic nature of so much of higher education, as I learned in teaching gigs and otherwise dealing with that sector.

In any event, we found the photos we needed in the real world.

Pictures of the shifting

Left: "Fragnet” (oil and graphite powder on canvas), by Kathline Carr; right: “Crane Beach” (photo), by Vicki McKenna, in their show together “Geographies of a Shifting World,’’ at Fountain Street Fine Art, Boston, through Oct. 25

The gallery says:

The two “share an interest in elemental landforms and geological processes. Carr’s drawings, paintings, and monotypes are in conversation with McKenna’s photography-based prints. They implicitly share an interest in human interaction with the natural world. Their current work has a common focus of climate change. Carr utilizes multiples and repetitious mark-making allowing patterns, gestures, and forms to represent her feelings of despair and hopelessness about current climate. McKenna’s photo illustrations combine multiple images intended to collapse present and future into one image that suggests the result of sea-level rise.’’

Panorama of Crane Beach in September 2007

— Photo by Thomas Steiner

Crane Beach is a gorgeous 1,234-acre state-owned conservation and recreation property in Ipswich, Mass., just north of Cape Ann. It has a four-mile-long sandy beachfront, dunes and a maritime pitch pine forest. Five and a half miles of hiking trails through the dunes and forest are accessible from the beachfront.

The land was given by the Crane family, whose fortune was from plumbing supplies. (One of the family bought my great-great grandfather’s house in Woods Hole, on Cape Cod. — Robert Whitcomb.)

Philip K. Howard: Misdiagnosing what has led to failed state America

People want answers for what went wrong with America’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic—from lack of preparedness, to delays in containing the virus, to failing to ramp up testing capacity and the production of protective gear. But almost nowhere in the current discussion can one find a coherent vision for how to avoid the same problems next time or help restore a healthy democracy.

Bad leadership has been identified as a primary culprit. The “fish rots from the head,” as conservative columnist Matthew Purple puts it. There’s plenty to blame President Trump for, but stopping there, as, say, former New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani does, ignores many bureaucratic failures. Cass Sunstein gets closer to the mark by focusing on how red tape impedes timely choices, but even he sees the bureaucratic structures as fundamentally sound and simply in need of some culling. Sunstein suggests that “it might be acceptable or sensible to tolerate a delay” in normal times, but not in a pandemic. Tech investor Marc Andreessen sees a lack of national willpower, an unwillingness to grab hold of problems and build anew. Prominent observers such as Francis Fukuyama, George Packer and Ezra Klein blame a broken political system and a divided culture; they offer little hope for redemption, even with new leadership.

All misdiagnose what caused government to fail here, and they confuse causes with what are more likely symptoms. Fukuyama rightly identifies a critical void in American political culture: the loss of a high “degree of trust that citizens have in their government,” which countries such as Germany and South Korea enjoy. But why have Americans lost trust in their government?

No doubt, after this is all over, a report will catalog the errors and misjudgments that let COVID-19 shut down America. The report will likely begin years back, when officials refused to heed warnings about pandemic planning. It will further expose President Trump, who for almost two months said that the coronavirus was “totally under control.” Errors of judgment like these are inevitable, to some degree—they happened before and after Pearl Harbor and 9/11, too—and with luck, they will inform future planning. The light will then shine on the operating framework of modern government, revealing not mainly errors of judgment, or cultural divisions, but a tangle of red tape that causes failure. At every step, officials and public-health professionals were prevented from making vital choices by legal obstacles.

Andreessen is correct that Americans have lost the spirit to build, but that’s because we’re not allowed to build. A governing structure that takes upward of a decade to approve an infrastructure project and ranks 55th in World Bank assessments for “ease of starting a business” does not encourage individual and institutional initiative. Of course Americans don’t trust government—it gets in the way of their daily choices, even as it fails to meet many national needs.

Our response to the COVID-19 missteps should not be to wring our hands about our miserable political system, or about the cynicism and selfishness that have infected our culture. We should focus on why government fails in making daily choices. What many Americans see clearly—but most public intellectuals cannot see—is a system that prevents people from acting on their best judgment. By re-empowering officials to do what they think is right, we may also reinvigorate American culture and democracy.

The root cause of failed government is structural paralysis. What’s surprising about the tragic mishaps in dealing with COVID-19 is how unsurprising they were to the teachers, nurses and local officials who are continually stymied by bureaucratic rules. A few years ago, a tree fell into a creek in Franklin Township, N.J., and caused flooding. A town official sent a backhoe to pull it out. But then someone, probably the town lawyer, pointed out that a permit was required to remove a natural object from a “Class C-1 Creek.” It took the town almost two weeks and $12,000 in legal fees to remove the tree.

In January, University of Washington epidemiologists were hot on the trail of COVID-19. Virologist Alex Greninger had begun developing a test soon after Chinese officials published the viral genome. But while the coronavirus was in a hurry, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was not. Greninger spent 100 hours filling out an application for an FDA “emergency-use authorization” (EUA) to deploy his test in-house. He submitted the application by e-mail. Then he was told that the application was not complete until he mailed a hard copy to the FDA Document Control Center.

After a few more days, FDA officials told Greninger that they would not approve his EUA until he verified that his test did not cross-react with other viruses in his lab, and until he agreed also to test for MERS and SARS. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) then refused to release samples of SARS to Greninger because it’s too virulent. Greninger finally got samples of other viruses that satisfied the FDA. By the time they arrived, and his tests began, in early March, the outbreak was well on its way.

Regulatory tripwires continually hampered those dealing with the spreading virus. Hospitals learned that they couldn’t cope except by tossing out the rulebooks; other institutions weren’t so lucky. For example, after schools were shut down, needy students no longer had meals. Katie Wilson, executive director of the Urban School Food Alliance and a former Obama administration official, secured an agreement in principle to transfer federal meal funding to a program that provides meals during summer months. But red tape required a formal waiver from each state, which in turn required formal waivers from Washington. The bureaucratic instinct was relentless: school districts in Oregon were first required to “develop a plan as to how they are going to target the most-needy students.” Meantime, the children got no meals. New York Times columnist Bret Stephens, interviewing Wilson, summarized her plea to government: “Stop getting in the way.”

What’s needed to pull the tree out of the creek is no different than what’s needed to feed school kids: responsible people with the authority to act. They can be accountable for what they do and how well they do it, but they can’t succeed if they must continually pass through the eye of the bureaucratic needle.

Reformers are looking in the wrong direction. Electing new leaders won’t liberate Americans to take initiative. Nor is “deregulation” generally the solution for inept government; the free market won’t protect us against pandemics. The only solution is to replace the current operating system with a framework that empowers people again to take responsibility. We must reregulate, not deregulate.

American government rebuilt itself after the 1960s on the premise of avoiding human error by replacing human choice. That’s when we got the innovation of thousand-page rulebooks dictating the one-correct-way to do things. We mandated legal hearings for ordinary supervisory choices, such as maintaining order in classrooms or evaluating employees. We replaced human judgment with rules and objective proof. Finally, government would be pure—almost like a software program. Just follow the rules.

For 50 years, legislative and administrative law has piled up, causing public paralysis and private frustration. Almost no one has questioned why government prevents people from using their common sense. Conservatives misdiagnose the flaw as too much government; liberals resist any critique of public programs, assuming that any reform is a pretext for deregulation. In the recent Democratic presidential debates, no one asked how to make government work better.

Experts have it backward. Polarized politics, they say, causes public paralysis. While hyper-partisanship certainly paralyzes legislative activity, the bureaucratic idiocies that delayed everything from COVID-19 testing to school meals had nothing to do with politics. Paralysis of the public sector came first, leading to polarized politics.

By the 1990s, broad public frustration with suffocating government fueled the rise of Newt Gingrich. The growth of red tape made it hard to make anything work sensibly. Schools became anarchic; health-care bureaucracy caused costs to skyrocket; getting a permit could require a decade; and Big Brother was always hovering. Is your paperwork in order? Americans kept electing people who promised to fix it—the “Contract with America,” “Change we can believe in,” and “Drain the swamp”—but government was beyond the control of those elected to lead it. What happens when politicians give up on fixing things? They compete by pointing fingers—“It’s your fault!”—and resort to Manichean theories and identity-based villains. Public disempowerment breeds extremism.

A functioning democracy requires the bureaucratic machine to return to officials and citizens the authority needed to do their jobs. That necessitates a governing framework of goals and principles that re-empowers Americans to take responsibility for results. Giving officials, judges, and others the authority to act in accord with reasonable norms is what liberates everyone else to act sensibly. Students won’t learn unless the teacher maintains order in the classroom. New ideas by a teacher or parent go nowhere if the principal lacks the authority to act on them. To get a permit in timely fashion, the permitting official must have authority to decide how much review is needed. To enforce codes of civil discourse—and not allow a small group of students to bully everyone else—university administrators must have authority to sanction students who refuse to abide by the codes. To prevent judicial claims from becoming weapons of extortion, judges must have authority to determine their reasonableness. To contain a virulent virus, public-health officials must have authority to respond quickly.

Giving officials the needed authority does not require trust of any particular person. What’s needed is to trust the overall system and its hierarchy of accountability—as, for example, most Americans trust the protections and lines of accountability provided by the Constitution. There’s no detailed rule or objective proof that determines what represents an “unreasonable search and seizure” or “freedom of speech.” Those protections are nonetheless reliably applied by judges who, looking to guiding principles and precedent, make a ruling in each disputed situation.

The post-1960s bureaucratic state is built on flawed assumptions about human accomplishment. There is no “correct” way of meeting goals that can be dictated in advance. Nor can good judgment be proved by some objective standard or metric. Judgments can readily be second-guessed, as appellate courts review lower-court decisions, but the rightness of action almost always involves perception and values. That’s the best we can do.

The failure of modern government is not merely a matter of degree—of “too much red tape.” Its failure is inherent in the premise of trying to create an automatic framework that is superior to human choice and judgment. We thought that we could input the facts and, as Czech playwright and statesman Vaclav Havel once parodied it, “a computer . . . will spit out a universal solution.” Trying to reprogram this massive, incoherent system is like putting new software onto a melted circuit board. Each new situation will layer new rules onto ones already short-circuiting.

Nothing much will work sensibly until we replace tangles of red tape with simpler, goal-oriented frameworks activated by human beings. This is a key lesson of the COVID-19 crisis. It’s time to reboot our governing system to let Americans take responsibility again.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, civic leader and photographer, is founder of Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left. This piece first ran in City Journal.

Another New England college now calls itself a university

Main entrance to Assumption University

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Assumption University, in Worcester, celebrates its new university status with a new Alma Mater sign.

“Assumption University invited the entire community to its virtual unveiling ceremony, which included a Mass and debut of the Alma Mater, following a performance from the Assumption University Chorale. The ceremony marked the formal transition from college the university.

“We are pleased the Commonwealth has affirmed our belief that Assumption is a comprehensive institution with exemplary undergraduate, graduate and continuing education programs,” said College President Francesco C. Cesareo, Ph.D. “Despite the challenges facing the higher education industry, through the devoted and energetic work of many throughout the campus community, we find ourselves at the cusp of yet another significant moment in the storied history of this institution that was founded in 1904 by the Augustinians of the Assumption.”

xxx

With the transition from Assumption College to Assumption University this year, Assumption reorganized into five schools: College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Grenon School of Business, School of Nursing, School of Health Professions and School of Graduate Studies.

xxx

Two well known New England universities — Dartmouth College and Boston College — stubbornly resist dropping “College” for “University.’’

Musical instrumentation in Bennington

Promotional picture for exhibition of musical instruments at the Bennington (Vt.) Museum through Dec. 31. The museum says:

“Each musical instrument in the Bennington Museum collection has its own unique story, but has remained silent for decades. The exhibit explores the histories and traditional sounds of the instruments and provides opportunities to hear them brought back to life in new compositions.’’

David Warsh: Best books

The main reading room of the Boston Public Library

— Photo by Hari Krishnan

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

There was for many years a photo on a hallway wall of our family home of an aged woman avidly reading in a canopied four-poster bed. The caption was a line from Henry David Thoreau: “Read the best books first, or you may not have a chance to read them at all.”

October Surprise: How the FBI Tried to Save Itself and Crashed an Election (Public Affairs), by Devlin Barrett, arrived last week, a day ahead of schedule. I read the first 20 pages standing up. I sat down and resumed reading, finishing the 325-page book the next day.

As a Wall Street Journal reporter covering the Justice Department, Barrett wrote two stories that may have affected the outcome of the election (neither of them available any longer for free on the Web). The first surfaced details of an unsuccessful bid for a Virginia state Senate seat by Dr. Jill McCabe, wife of Deputy FBI Director Andrew McCabe, in which her campaign received a large contribution from then-Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a longtime friend of Bill and Hillary Clinton. The second disclosed the existence of an ongoing FBI investigation of the Clinton Foundation. Between the first and the second, FBI Director James Comey notified Congress that he had reopened the Clinton e-mail investigation.

Donald Trump won the election by a razor-thin margin. A couple of months later, Barrett moved to The Washington Post, where he continued to cover the growing turmoil at the FBI, often with fellow reporter Matt Zapotosky.

In 2017, Comey was fired, former FBI director Robert Mueller was hired as special counsel to investigate links between the Trump campaign and Russia. Investigation of the leaks to Barrett began. Senior FBI investigator Peter Strzok was dismissed from the Mueller task force, after a series of texts he exchanged with FBI attorney Lisa Page was uncovered. Eventually the inspector general of the Justice Department went to work on the case. The running narrative of the Strzok-Page text eventually was published.

Barrett has weaved all these complicated elements into a spell-binding account that is in equal measure knowledgeable, intelligible, and fair-minded. Not since All the President’s Men, by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, has there been anything like it. In October Surprise, it is an intelligence service and law-enforcement agency, not a presidency, that comes apart. And Barrett, like Woodward and Bernstein, is coy about his most important sources. In the end, though, Barrett’s is the more thorough explanation.

That said, it is more than a little confusing to read so soon before the 2020 election, since it has almost entirely to do with the Justice Department and the FBI, and little to do with the broad choices now facing American voters. That’s why it’s a book, not a newspaper story. For that reason, it will take some time for the book to arrive at the center of public discussion. (The Post ran an excerpt from it on the front page, followed by a review.) Moreover, Barrett’s conclusion, that the harm arose from the FBI trying to save itself, failed to persuade me. But what a stupendous achievement is his untangling of the web of alarms and confusions!

xxx

What are the best business books of today? Of the newspapers and reviews I read to keep up with general-interest publishing in and around economics, the most useful by far is the Financial Times. Book reviews appear without warning throughout the week. The weekend edition’s Life and Arts section is almost always ahead of the curve. There are special sections in summer, autumn, and winter, in which staffers survey new books on their beats.

And then there is the annual FT McKinsey Best Business Book contest, an international agenda-setting device. You can test your sophistication against its long lists here, or catch up in a hurry on what you have missed.

Now in its 17th year, the FT prize has become a reliable indicator of cosmopolitan fashion in ideas, “making sense of the near future,” as a panel discussion put it last week. (For a time Goldman Sachs was sponsor.) To make its point, the contest offers big prizes, £30,000 to the winner, £10,000 each for five runners-up. A panel of though-leader judges, chaired by incoming FT editor Roula Khalaf, assures global reach: Mitchell Baker, chairwoman of the Mozilla Foundation; Mohamed El-Erian, economic advisor at Allianz; Herminia Ibarra, of London Business School; Randall Kroszner, of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business; Dambisa Moyo, economist and board member, 3M Company and Chevron; Raju Narisetti, of McKinsey & Co., and Shriti Vadera, chair-elect of UK’s Prudential PLC.

Fifteen titles were named to a long list. The judges chose six, which were announced last week:

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Princeton University Press (UK) & (US)

No Filter: The Inside Story of How Instagram Transformed Business, Celebrity and Our Culture, by Sarah Frier, Random House Business (UK); Simon & Schuster (US)

No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention, by Reed Hastings and Erin Meyer, WH Allen, Penguin Random House (UK); Penguin Press (US)

Reimagining Capitalism: How Business Can Save the World, by Rebecca Henderson, Penguin Business, Penguin Random House (UK); PublicAffairs (US)

If Then: How the Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future, by Jill Lepore, John Murray Press (UK); W.W. Norton (US)

A World Without Work: Technology, Automation and How We Should Respond, by Daniel Susskind, Allen Lane (UK); Metropolitan Books (US)

The winner will be announced Dec. 1 at a ceremony in London.

Judges haven’t shied from books on weighty topics. Capitalism in the twenty-first century, by Thomas Piketty, won in 2016, Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crisis Changed the World, by Adam Tooze, made the long list in 2018. Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought, by Andrew Lo, and The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality, by Walter Scheidel, made the short list in 2017. The Rise and Fall of American Growth, by Robert Gordon, made the short list in 2016, while Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World, by Deirdre McCloskey, made the long list.

There have been interesting omissions. Three in particular stand out, because they represent an unusual degree of convergence on the importance to economics, at least as it has long been understood, of institutions and culture. The three books are:

A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy, by Joel Mokyr, of Northwestern University.

The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty, by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Chicago, respectively

The Decline and Rise of Democracy: A Global History from Antiquity to Today, by David Stasavage, of New York University.

No selecting mechanism is perfect, or even near perfect. And global thought-leaders don’t have time for heavy lifting. The Best Book prize is as well-focused on the news frontier as any other forward-looking instrument we possess.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Get me back east

The Ethan Allen Homestead, in Burlington, Vt.

“….Before the grandest vista

I’ll ever witness, what I wanted most

desperately was to trim the hedge and mow

the grass at Thirty-Four North Williams Street,

Burlington, Vermont Oh Five Four Oh One’’

— From “Idaho Once,’’ by David Huddle

Chris Powell: How much can Connecticut bear?

A black bear, of the only bear species found in New England

Connecticut's bear population, estimated at 800, is growing "exponentially," a newspaper reported the other day. This was a bit hyperbolic, since after 800 the next level in an exponential series is 800 times 800 -- 640,000 -- and the bear population will not be increasing that quickly.

But 640,000 bears in Connecticut will be the inevitable outcome unless the state's largely indifferent policy toward them is radically changed. That policy is simply to advise the public not to feed the animals -- to secure trash cans, outdoor grills and bird feeders and to hope the bears stop breaking into houses and attacking domestic animals. If that policy was accomplishing anything, there wouldn't be 800 bears in the state already and their population wouldn't be growing, "exponentially”"or just fast. So in another 10 years or so this policy is bound to leave most towns with many bears bumping into each other as they are shooed away from one neighborhood to the next.

State government's animal-control people are tiring of anesthetizing tagging and relocating troublesome bears, increasingly inclined to tell frantic callers just to let the animals move along and frighten someone else. But as the bear population grows, the animal-control people may be compelled to do a lot more relocations, even as the remote forests to which the bears are taken fill up with them and make them even more eager to return to less competitive neighborhoods.

The alternative to having bears everywhere is for state government to authorize a bear-hunting season, maybe even paying bounties to hunters. But just musing about hunting bears makes certain wildlife lovers hysterical.

Bears are cute -- at a safe distance anyway. A few may contribute some excitement to Connecticut's ordinarily placid suburban atmosphere. But a dozen or more in every town will not be cute. They will cause perpetual panic and frequent damage and injury.

Connecticut already is full of deer, which are cute too and often a delight to see with their fawns. Bucks, while rarely seen, can be majestic.

But deer are not a delight when they dart in front of cars and get hit, damaging vehicles and injuring their occupants, or when they munch on plantings, gardens, orchards, and farm fields.

So Connecticut has some deer-hunting seasons, and there is little clamor to repeal them. Don't try telling farmers how cute deer are. Having worked so hard to get the earth to produce, farmers can obtain state permits to shoot deer on their property year-round to protect the fruit of their labor.

Enacting a bear-hunting season would eliminate the need for much more hunting in the future and thus be far kinder to the animals in the long run. But does Connecticut have any elected officials with the courage to admit that you can't always be friends equally with people and animals?

It's not just bears. How many coyotes, bobcats, weasels and such does Connecticut really want to endure? Nature is not always warm and cuddly. It often has sharp claws and teeth.

But since Connecticut is not very good at facing up to policy failures and the special interests behind them, dozens of bears in every town may be necessary before the General Assembly and the governor enact something more in the public interest than laissez-bear.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

'Turnpikes to free thought'

Cobblestoned Acorn Street, on Beacon Hill

“Boston is full of crooked little streets but I tell you that Boston has opened and kept open more turnpikes that lead straight to free thought and free speech and free deeds than any other city of live men or dead men.’’

— Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894), physician, poet and essayist and father of famed Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

xxx

A Little, Brown and Co. insignia used in 1906. Little Brown was founded in Boston and stayed there until the late 20th Century. It has published many famous New England and other authors since its founding, and it helped make Boston for many years the leading book-publishing city in America and Boston a literary mecca.

"The assertion that Boston was the literary center during the period in which American literature acquired a shelf of its own in the library of the race is hardly open to dispute."

— M.A. DeWolfe Howe (1864-1960), author and editor

Watch out for the glare

“FaceSwipeStill2,’’ by Joseph Fontinha, at Fountain Street Fine Art, Boston

Expand the charm north in Newport

Of course not every neighborhood in Newport can look like this 18th Century section of “The City by the Sea.’’

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Newport is a fascinating little city, with its dramatic coastline, history, architecture and thick demographic/ethnic stew. And now there’s an interesting battle underway over how to redevelop its North End, a neighborhood with lots of low-income poor people and rather ugly cityscape. Visually, it sometimes seems that there’s “no real there there,’’ as Gertrude Stein said famously about Oakland, Calif.

I just hope that the final plan doesn’t result in making it look like a suburban-style shopping center/ office park with much of the space taken up by windswept parking lots. To show that it’s part of a city much of which is famous for its beauty, it should look like part of a city, with the density of one, and with green parks as well as a mix of new housing – resident-owned and rental -- stores and restaurants (with space for outdoor service) whose design speaks to the most attractive aesthetic traditions of the area. Newport is well known for its extremes of wealth and poverty. Thoughtful redevelopment of the North End can at least attempt to provide the unrich there with the opportunity to live in a neighborhood with the sort of built beauty than improves their socio-economic, as well as psychological, health, including by drawing in some of the visitors, and their wallets, who previously only went to the famous historic areas in the southern part of the city.

Village center on Block Island

I spent a day and night on Block Island last week: Gray skies, gray water, gray buildings and lots of red pants.

What we have

“New York has people, the Northwest rain, Iowa soybeans, and Texas money. New Hampshire has weather and seasons.’’

Donald Hall (1928-2018) in Here at Eagle Pond, essays about the poet’s home turf ,in very rural Wilmot, N.H.

xxx

“Some of us spend our lives preferring Fall to all the seasons …taking Spring only as prologue and Summer as the gently inclined platform leading all too slowly to the annual dazzle.’’

— Mr. Hall in Seasons at Eagle Pond

Wilmot Baptist Church

Llewellyn King: Oh for real conservative values, not Trumpism

President Gerald Ford, in 1974. He was a true conservative.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

If Mitch McConnell’s toadying Senate has its way, we are to have a more conservative U.S. Supreme Court come the elections in November, even though it looks like the current concept of harsh conservatism will be roundly rejected in them.

One branch of government, if President Trump and McConnell have their way, will be handed over to an extreme vision of conservatism that has no deep-seated philosophy behind it. It is a corruption of a noble stream of political thought and its consequence is a political class that adheres to narrow, divisive issues that have an oppressive social effect. Taken together these have the result of seeming to be heartless and causing pain to the poor and under-educated.

That isn’t the conservatism we had known for decades: the conservatism of Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan and the two George Bushes. It is a political virus that threatens the Grand Old Party with years of loss of elective office.

If these new aberrant Republicans use their form of judicial activism to keep alive Trumpism, they will be ensuring today’s ugly discord for a long time.

The issues that divide us aren’t the solid Republican values of yesteryear of limited government, free trade, market solutions, open opportunity, strong defense, active scientific inquiry, educational excellence, personal freedom and privacy and universal prosperity. Not the cramped and spleen-imbued issues that are about to dominate the Senate GOP’s foraging for like-mindedness in the coming hearings.

They are out to burden conservatism with narrow views on a few issues that aren’t intrinsically conservative, including:

· Abortion

· The death penalty

· Health care

· Sexual preference

Rigidity on these matters – except for sexual preference -- has the effect of laying a disproportionate burden on the poor and, therefore, stimulating the far left of the Democratic Party, empowering the followers of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D.-N.Y.).

Take just two matters. The abortion issue falls heavily on the poor. Nobody suggests that it is a good means of birth control, but unwanted pregnancies do occur. They can break up families, cause economic burdens and bring children into untenable poverty, social dysfunction and other misery.

What women do in private shouldn’t be governed by the Senate or the court.

End Roe v. Wade and rich women will still be able to go to another country or in other ways pay for a safe end to a pregnancy. Appointing a staunch religious anti-abortionist to the Supreme Court is to put a thumb on the scales of justice and to blur the line between church and state for a transient political purpose: reelecting Trump.

The death penalty, which has failed spectacularly as a proven deterrent to murder, likewise falls mainly on the poor -- often the poor and mentally challenged. The record shows that rich people aren’t taken to the death chamber at dawn. Superior lawyering from the moment of arrest keeps them from later capital punishment. What is the ultra-conservative value proposition then?

The same imbalance extends throughout our remarkably punitive legal system that punishes those on society’s bottom rungs more aggressively than those at the top.

Families were destroyed and social mayhem resulted in the mortgage excesses of the last financial crisis. I saw it devastate one of my employees of that time: a struggling Black man of impeccable character but limited education who was talked into unwise refinancing by rapacious mortgage lenders. He lost his home, his good name, everything. No one across the length and breadth of the scandal went to prison for the damage that their greed inflected.

All the other right-wing issues of the day have the same characteristics: They defend the upper reaches of society, those with money, and are harsh and inconsiderate of the rest.

Health care glares in this. A patchy and capricious system will become worse for tens of millions of Americans if the legal attack on the Affordable Care Act by the Trump administration goes against the sick in the Supreme Court — a court weighted against ordinary people in pursuit of a suspect interpretation of conservatism.

Radical conservatism is also out to extinguish the labor movement, or what is left of it. A robust labor movement is a bulwark against the pitiless downgrading of the worker from dignity to subservience, living in fear and rewarded inadequately.

The rush to the bottom is becoming a national sink hole. We can all fall into it eventually.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Don Pesci: The pesky ‘science’ and politics of COVID-19

Coronavirus seen with electron microscope

VERNON, Conn.

The New York Times, the old gray lady of Eastern Seaboard journalism, published a blockbuster story on Aug. 30, “Your Coronavirus Test Is Positive. Maybe It Shouldn’t Be,” that should be widely reported in other media formats. So far, the substance of the story has remained pretty much on the media shelf.

The Times has discovered that the easily corrected, most often used calibration for Coronavirus testing is not useful for "containing the spread of the virus.” The Coronavirus, of course, causes the disease named COVID-19.

According to The Times, “In three sets of testing data that include cycle thresholds, compiled by officials in Massachusetts, New York and Nevada, up to 90 percent of people testing positive carried barely any virus, a review by The Times found.

“On Thursday (8/10/2020), the United States recorded 45,604 new Coronavirus cases, according to a database maintained by The Times. If the rates of contagiousness in Massachusetts and New York were to apply nationwide, then perhaps only 4,500 of those people may actually need to isolate and submit to contact tracing.

The difference between 45,000 and 4,500 is, scientists and reporters may note, not a rounding error.

Leading public-health experts are concerned: “Some of the nation’s leading public-health experts are raising a new concern in the endless debate over Coronavirus testing in the United States: The standard tests are diagnosing huge numbers of people who may be carrying relatively insignificant amounts of the virus,” The Times reported.

To put the matter in terms that non-scientists may understand -- current Coronavirus testing is so over calibrated it cannot discover the four leaf clover in a massive field of clover.

“The most widely used diagnostic test for the new Coronavirus, called a PCR test,” the paper notes, “provides a simple yes-no answer to the question of whether a patient is infected.” However, similar PCR tests for other viruses, “do offer some sense of how contagious an infected patient may be: The results may include a rough estimate of the amount of virus in the patient’s body.”

Dr. Michael Mina, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, is calling for testing that can find the four leaf clover: “We’ve been using one type of data for everything, and that is just plus or minus — that’s all. We’re using that for clinical diagnostics, for public health, for policy decision-making.’’

But yes-no isn’t good enough, he says, according to The Times story. “It’s the amount of virus that should dictate the infected patient’s next steps. ‘It’s really irresponsible, I think, to forgo the recognition that this is a quantitative issue.’”

The problem is that current PCR tests are imprecisely calibrated. The PCR test, “amplifies genetic matter from the virus in cycles; the fewer cycles required, the greater the amount of virus, or viral load, in the sample. The greater the viral load, the more likely the patient is to be contagious.” The cycle threshold -- the “number of amplification cycles needed to find the virus… is never included in the results sent to doctors and Coronavirus patients [emphasis mine], although it could tell them how infectious the patients are.”

The Times story quotes Juliet Morrison, a virologist at the University of California at Riverside: “I’m shocked that people would think that 40 could represent a positive,” And Dr. Mina, who would set the cycle threshold limit at 30 or less, agrees. The change would mean, according to The Times’s story, “the amount of genetic material in a patient’s sample would have to be 100-fold to 1,000-fold that of the current standard for the test to return a positive result — at least, one worth acting on.”

Currently, the cycle threshold limit is set at 40, which means that you are “positive for the Coronavirus if the test process required up to 40 cycles, or 37, to detect the virus.”

However, “’Tests with thresholds so high may detect not just live virus but also genetic fragments, leftovers from infection that pose no particular risk — akin to finding a hair in a room long after a person has left, Dr. Mina said.”

And the figures deployed by most politicians, in the absence of more useful and predictive figures, are designed to induce in ordinary citizens a posture of compliance to gubernatorial edicts that depend upon medically useless data.

The Times, not a Trump apologist, quotes another virologist: “It’s just kind of mind-blowing to me that people are not recording the C.T. values from all these tests, that they’re just returning a positive or a negative.”

Not for nothing is Coronavirus called a “novel” virus. There can be no “science” associated with a novel virus. But there are scientists, continuing research, and necessary adjustments in perceptions and medical data. One wonders how many doctors and reporters in Connecticut would be thunderstruck, as were Mina and Morrison, that the “yes and no” figures dangled before them were, to put the best face on it, medically misleading but politically useful.

Don Pesci is a columnist based in Vernon.

SHARE

Wind-powered landscape

“Dunes Ride In’’ (photo) by Trish Crapo, in her show at the Hampden Gallery, at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, through Oct. 7

The gallery says:

”Through photographs, video and spoken word, Leyden, Mass., artist Crapo explores if wind, a clothesline, and a white nightgown can summon someone from the other side. She has been awarded the Dunes Shack Residency, at the Cape Cod National Seashore, two times.’’

Frizzell Hill, looking west towards the town center of Leyden, Mass. (pop 711), on the eastern side of The Berkshires and home of Trish Crapo

Leyden Town Hall

AMC keeps its doors open

Artist Samuel Lancaster Gerry's 1877 depiction of Pinkham Notch, entitled "Tuckerman Ravine and Lion's Head,’’ which are on Mt. Washington. The Appalachian Mountain Club’s largest lodge — the Joe Dodge Lodge — is in Pinkham Notch.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“The Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC), an outdoor-focused nonprofit organization, has embraced innovative strategies to keep doors open and continue foster the enjoyment and protection of the outdoors.

‘‘The COVID-19 pandemic had dealt an immediate blow to the AMC, and the nonprofit was forced to fast track fundraising and allocate their resources strategically. AMC prioritized conservation projects, citizen science and conservation policy, focusing on the recently passed Great American Outdoors Act. The AMC also prioritized a small group of caretaker staff, who have continued to provide basic services at the White Mountain huts along with safety functions.

“‘The AMC is a strong community of outdoor enthusiasts and conservation stewards. This group of stalwart supporters and volunteers has been key in helping us manage through and lessen the overall impact of the pandemic on AMC’s mission,’ CEO John Judge told the Boston Business Journal. “Inherent in our model is the way we help people experience the outdoors in a communal way — this includes folks eating meals together, naturalists programs for schools, group travel, and overnight accommodations in bunkhouses.”

“The New England Council congratulates the Appalachian Mountain Club on continuing to conserve and promote the enjoyment of the outdoors despite this year’s challenges. Read more from the Boston Business Journal.’’

Very strange summer and now a fearsome fall

Time to jump? Fall foliage at Lake Willoughby, in Vermont

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

As we slip into the mellow season (except for politics), and we start to crunch dry brown fallen leaves on the sidewalks, I’ve been thinking about how we lived during this pandemic summer.

Yes, it was sometimes claustrophobic and included far too many repetitive activities (recalling the movie Ground Hog Day) but the warm weather made it easier to spend a lot of time outside, when it wasn’t too warm. It was also easier because there’s been little rain, which is mostly bad: We’re in a severe enough drought that woodland fire warnings were posted last week for southern New England. (You start to unduly worry about global warming and something like the West Coast fire catastrophe happening here. The lawns have looked as if desertification is getting started.)

Thank God that the pandemic didn’t start last November, at the start of our mostly indoors season.

Many of us fortunate enough to have a porch or backyard have found seeing friends there very pleasant, and safe enough to please most worrywarts about COVID-19. That’s not to say that social distancing and marks don’t make it harder to understand each other. I wonder if hearing-aid sales have surged since last winter. I hear a lot of shouting, including my own.

Meanwhile, we walk, walk, walk and wear out our dogs.

As for dining out at restaurants, we’ve done it inside and out. I prefer inside to avoid the street noise, car fumes, yellow jackets, jackhammers, leaf blowers, sidewalk lunatics and other distractions. Ignore the theatrics of “deep cleaning.’’ The chances of getting COVID from touching something are remote. It’s an air problem! Does the restaurant has a good HVAC system? Can all its windows be opened wide? Of course, some people won’t go to any public places. How long will they keep that up? I confess I’m not much of a COVID alarmist and do have claustrophobe tendencies. But often when I suggest meeting people at a restaurant or coffee shop the response is an anxious “no, not yet.’’

It’s been tougher than we had expected early this summer to travel even within New England because of testing rules, with frequent delays in getting results, and the 14-day quarantine orders. Maine is particularly draconian – very heavy fines. Still, after adjusting to that challenge, consider that there’s lots to see in our compact region, a relief for those for whom the pandemic makes traveling further afield impossible. Consider that maps show that Americans aren’t welcome in most of the world now, including – how embarrassing! – Canada. Close to home, the likes of the Maine Coast and the Green Mountains are well worth the aggravation of a test. However, that COVID has closed many roadside attractions (my favorite are old-fashioned diners for breakfasts) is dispiriting.

This is an anxious time in America: A vicious pandemic that has killed almost 200,000 and clipped everyone else’s wings, a deep recession, a mobster/treasonous president and his sycophant enablers, the expansion of dictatorship around the world and scary symptoms of man-made global warming, of which the West Coast fires and the population explosion of tropical storms are just current examples.

(Speaking of Trump’s enablers, read about Michael Caputo, the Looter in Chief’s propaganda minister and re-election-campaign manager at the Department of Health and Human Services:

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/elections/2020/09/15/michael-caputo-election-violence-conspiracy-theories/5802225002/

He’s a fitting representative of the Trump regime.)

Whatever, it’s a beautiful time of the year hereabouts – mild, still verdant (where watered) and increasingly colorful until that first heavy frost silences the cicadas and crickets for good. Let’s wander outdoors as much as we can. In the long run we’re all dead.

The late Hartford-based poet and insurance executive Wallace Stevens wrote: “The most beautiful thing in the world is, of course, the world itself.’’

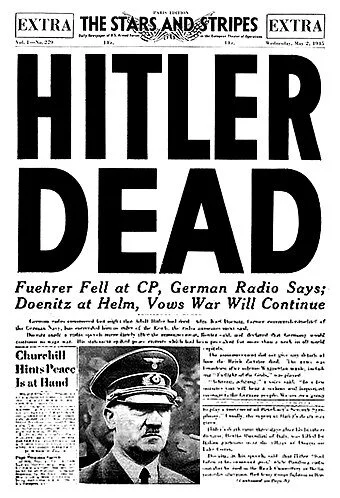

David Warsh: What I learned working for Stars & Stripes

The May 2, 1945 issue of Stars & Stripes

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

If we could look back on the Trump administration from the vantage point of 50 years from now, it might seem that the only authentic heroes it produced were a pair of retired generals and war commanders whose good conduct as civil servants ranked with that of another such exemplar of 60 years before, President Dwight Eisenhower. I mean John F. Kelly and James Mattis.

As White House chief of staff and secretary of defense, respectively, Mr. Kelly and Mr. Mattis demonstrated the qualities of devotion to duty and restraint we hope for from former military commanders who choose to become involved in politics. What to do about the military newspaper Stars and Stripes? Why not consult Kelly and Mattis while they are still here?

The Defense Department, you’ll remember, disclosed in February that it planned to close the 150-year old newspaper, which publishes four print editions for U.S. troops abroad (in Europe, the Middle East, Japan and South Korea) and seven digital editions for all the rest. Earlier this , the Pentagon made the closing imminent: Offices would close Sept. 30, the organization dissolve by Jan. 31. There was no telling where the impulse came from. The operation loses $15 million a year – 0.005 percent of a $700 billion total Defense budget. Senators from both parties objected, President Trump tweeted his opposition, and the decision was rescinded.

The question of whether or not to shut down the newspaper is one of long-term planning, not short-term budgeting. Might America have to wage another war? If so, what kind? With what sorts of weapons? Of what duration? The present professional army? Or a conscripted one? Requiring what degree of sacrifice? On the part of armed forces? The civilian populace? Might Stars and Stripes be needed again someday?

There is no way of telling. You would have thought there could never be another Vietnam, with as many as half a million troops deployed for a decade on the far side of the world – until the U.S. invasion of Iraq, with its plans to build an embassy that by 2012 would employ 16,000 persons. Today such an extended foreign war seems more unlikely still. But what about the possibility of engagements in the Western Hemisphere? Of involvements in the Arctic, or in the continental United States themselves, in the aftermath of an act of nuclear terrorism? A digital disabling? An extended defense of the borders in the event of a hemorrhagic fever pandemic? Of severe climate change? Or global famine?

More than 50 years ago I spent a year, as an enlisted sailor, working for Stripes as a staff reporter, in 1968-69. I learned that the newspaper was valuable indicator on the instrument-panel of America’s hard-to-follow war – a gauge of enthusiasm, a back channel to the Pentagon, a steam valve for soldiers in the field, a focal point for diverse and lively points of view. More than that, the newspaper was a symbol more profound than the flag itself, an elaboration of American values printed six days a week and circulated throughout the far-flung empire of Americans stationed abroad.

I am not suggesting calling up Kelly and Mattis and asking them what to do. At most, their views of what might be required to keep an American army in the field for any length of time in future wars is one more topic to be covered in their after-action reports and biographies. It does make sense, however, to put oneself in their place. Would either man, concerned about the powers of commanders in the future, recommend shutting down or selling off as surplus a potential adjunct to future campaigns that had proved so valuable in the past? I doubt it.

Perhaps there will be no other wars. I hope there will be none. But should there be, what I learned from Stars and Stripes is that freedom of the press, even when the press belongs to the Defense Department, is a strangely powerful rhetorical lever in support of American might. Stripes is likely to prove as valuable in adverse circumstances in the future as it has been in the past. There is no good reason to take it down.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Fresh as a new year

Sumac fruit and sycamore tree (below) in autumn

— Photo by Fanmartin

“Last night the first light frost, and now sycamore

and sumac edge yellow and red in low sun

and Indian afternoons. One after another

roads thicken with leaves and the wind

sweeps them fresh as the start of a year…’’

Preston Congregational Church

— From “Long Walks in the Afternoon,’’ by Margaret Gibson (born 1944), a former Connecticut poet laureate. She lives in Preston, Conn., in the southeastern part of the state.