‘Regimented chaos’

"Crack an Egg on your Head, Let the Yolk Drip Down, Seesaw" (flocking, resin, wood, metal, and mixed media), by Greater Boston-based artist Meagan Hepp, in her show “Play Date: Companions Club, at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Oct 2.

The gallery says:

“Meagan Hepp’s work balances advanced planning with chance. Each Companion is made from a base of flocking and resin and is mixed with found objects, acting as a catalyst for regimented chaos. The Companions in the installation are based on nostalgic toys and pop culture references from the late 1990s and early 2000s that specifically resonate with Hepp’s childhood. Hepp combines discarded plywood, disco ball mirror, and other recycled materials taken from everyday life to give each piece a distinct personality, in a way creating a three-dimensional puzzle. Finding themself suddenly cut off from their social networks and communities during the COVID-19 crisis, Hepp began to think of their sculptures as company. As these sculptural friends started to accumulate and interact with the furniture, architectural built-ins, and everyday objects in Hepp’s home-studio, Hepp found themself yielding their space to what began to feel like a ‘Companion playground’’’.

Our clever masked neighbors

They’re watching you. The raccoon's social structure is said to be grouped into what Ulf Hohmann calls a "three-class society".

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

As a reminder that humans are far from the only intelligent creatures around us, consider raccoons -- those wily, rather distant relatives of bears who have learned how to thrive in suburbia and cities. They may be smarter than dogs. We have some charming families of them near us in our Providence neighborhood. We see their heads pop out of holes in trees, stormwater culverts and other refuges. But cute as they are, don’t get too close to them. They’re wild animals, which can become very aggressive if they feel threatened, and you don’t want to be bitten or scratched by them. And, rarely, some contract rabies.

Their ability to get around our impediments in order to grab food seems to strengthen over the years. That may be because the smarter ones are more likely to survive and pass on their genes.

In any case, their dexterity and ingenuity (they’re good at opening trash cans, boxes and other manmade objects), not to mention their bank-robber-style masks, make them great fun to watch – from a few feet away. I love seeing them use their hands, or rather front paws, with five long, tapered fingers and long nails. They lack thumbs, so they can't grasp objects with one hand/paw as we can, but they use both forepaws together to lift and then manipulate objects with a curious elegance. If they also had opposable thumbs like us, we’d be in big competitive trouble.

Cherry tomatoes may give you the best value of vegetables you plant, at least within the limitations of city or suburban space. They grow fast, don’t take up much room and each plant produces lots of tomatoes, which serve as easy snacks. The main drawback is that they require a hell of a lot of water.

We recently planted a second crop, which should do well in our increasingly warm late summers and autumns. Maybe a third crop, too?

But raccoons, which are omnivorous like us, like tomatoes too. So you might want to sprinkle some Critter Ridder or similar product near your plantings.

Frank Carini: In search of old-growth forests

An old beech tree in the Rhode Island woods.

— Photo by Frank Carini

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

WARWICK, R.I. — Last winter Nathan Cornell accidentally found himself “walking into a different world,” one that isn’t protected from human intervention. For the past two years, the University of Rhode Island graduate has been searching for old-growth forests in Rhode Island.

He found one not far from his Warwick home.

His hunt for old-growth forests led him and Rachel Briggs to found the Rhode Island Old Growth Tree Society, a nonprofit determined to locate, document, map and advocate for the preservation of all remaining old-growth and emerging old-growth trees and forests in the state. This means trees and groups of trees that are 100 years old and older.

Cornell, with the help of licensed arborist Matthew Largess, owner of Largess Forestry, in North Kingstown, R.I. has so far identified more than a dozen potential old-growth pockets, including on the University of Rhode Island campus in South Kingstown and in Cranston, North Kingstown, Portsmouth, Warwick and West Greenwich.

In mid-July, the 24-year-old took this ecoRI News reporter on a walking tour of the hidden-in-plain-sight “5- to 10-acre” Warwick property owned by the Community College of Rhode Island and Kent Hospital. To listen to the audio story, click the bar at the top.

Anyone interested in joining the Rhode Island Old Growth Tree Society, can contact Cornell at ncornell@my.uri.edu. To read an opinion piece written by Cornell and recently published on ecoRI News, click here.

Frank Carini is co-founder and a journalist at ecoRI News.

David Warsh: In Ukraine, echoes of Vietnam

— Map by Amitchell125

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The most interesting news around in August was the debut of a major series in The Washington Post about the beginnings of the war in Ukraine. Clearly it is intended to be an entry in next year’s contest for a Pulitzer Prize.

The first installment, “Road to war: U.S. struggled to convince allies, and Zelensky, of risk of invasion,” was a ten-thousand-word blockbuster.

The second, “Russia’s spies misread Ukraine and misled Kremlin as war loomed,” ran another six thousand words.

The third, “Battle for Kyiv: Ukrainian valor, Russian blunders combined to save the capital,” was similarly substantial.

And yesterday, a story appeared, not part of the series, about a disaffected Russian soldier who fled the war, featuring lengthy excerpts from his journal. “‘I will not participate in this madness.’”

Plenty of news, but the most striking aspect of the series is its architecture. The Post so far has mostly omitted the Russian side of the story. This is, to put it mildly, surprising. It is always possible that much more background narrative is yet to come. “Begin toward the end” is a story-telling recipe frequently employed in novels and films, but the ploy is not common in newspaper series. On the other hand, given the customary wind-up of important series in December, it is entirely possible that eight or even ten more installments are on the way.

For simplicity’s sake, the analytic foundations of the Russian version of the story rest mainly on three documents. The first is U.S. Ambassador William Burns’s Feb. 1, 2008 cable from Moscow, “Nyet means Nyet: Russia’s NATO Enlargement Redlines’’. We know about this thanks to Julian Assange and Wikileaks.

Burns reported that RussianForeign Minister Sergey Lavrov and other senior officials had expressed strong opposition to Ukraine’s announced intention to seek NATO membership, stressing that Russia would view further eastward expansion as “a potential military threat.” President George W. Bush ignored Burns’s advice and President Obama pressed ahead, backing a second pro-NATO “Orange Revolution” in 2014 that caused a pro-Putin Ukrainian president to seek safety in Russia., Putin annexed the Crimean peninsula in response.

The second is Putin’s long word essay from August, 2021, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’’. That, Angela Stent and Fiona Hill argue differently in the new issue of Foreign Affairs, may matter much to citizens of NATO nations and, especially, the leadership of Ukraine, but Putin’s argument matters more to most Russians and some Ukrainians.

The third is the little-publicized and scarcely noticed U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership of November 10, 2021. After that, there could be no reasonable doubt among the well-informed on any side that the invasion would take place.

The real news had to do with maneuvering between the US diplomats and military commanders and Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky that took place on the eve of the war. The U.S. emphasized the near certainty of invasion and sketched three alternative possibilities the Ukrainian might pursue: move his government to western Ukraine, presumably Lvov; to Poland, a member of NATO; or remain in place.

Zelensky chose to remain in Kyiv, while discounting the likelihood of invasion to his fellow citizens, seeking to avoid panic. In an interview with Post reporters, he was candid about his reasoning. A follow-up story, “Zelensky faces outpouring of criticism over failure to warn of war,” described the political turmoil that erupted thereafter in Ukraine. A full transcript of the interview followed four days later.

The subtext so far of The Post’s series reminded me of a little-remembered year or two in the early ‘60’s, before the dramatic escalation of the war in Vietnam took place, an episode usually glossed over, but well documented in Reporting Vietnam, Part One: American Journalism, 1959-1969 (LOA, 1998). The world was more mysterious in those days; there were fewer players on the stage.

Three correspondents for U.S. newspapers stood out for their short-lived enthusiasm for the fight against the Communists: David Halberstam, of The New York Times; Neil Sheehan, of the Associated Press; and Malcolm Browne, of United Press International. Feeding them tips were CIA agent Edward Lansdale, battlefield commander John Paul Vann, and, perhaps, RAND consultant Daniel Ellsberg, then himself a hawk. These three charismatic leaders and others on the outskirts of what was then a U.S. advisory group believed that the war against the insurgents could be won if only it were better fought. As Lansdale put it:

It’s pure hell to be on the sidelines and seeing so conventional and unimaginative an approach being tried. About all I can do is continue putting in my two-bits worth every chance I get to add a bit of spark to the concepts. I’m afraid that these aren’t always welcome.

In South Vietnam, the alliance between Catholics and Buddhist broke down after 1963, and before long the U.S. military took over the war itself. Ten more years and millions of lives were required to lose it to North Vietnam.

No such option exists in Ukraine: Ukrainians must fight the war on their own, however powerful are the weapons they are given. Domestic support for the admirable Zelensky may turn out to to be no more durable over the long haul than consensus among his NATO backers. Putin is a bully, but he seems no less formidable than was Ho Chi Minh. And though Putin is angry, he is not mad.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

A great discovery

Ripe, ripening, and unripe blackberries

"It was then that I made one of the great

discoveries of my young and very sensual life:

blackberries aren't really black, they're

deep purple; and they make home-made ice cream

just about the sexiest thing a sun-burned kid

can put in his mouth this side of hot, ripe

peaches, purloined from a neighbor's tree.’’

— From “Blackberries,’’ by John-Michael Albert (born 1951), a Portsmouth, N.H.-based poet

—

Chris Powell: Education disaster begins with parental neglect

Possible ways for such adverse childhood experiences as abuse and neglect to influence well-being through the lifespan, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

August's Titanic Deck Chairs Rearrangement Award seems likely to be won by the Education Committee of New Haven's Board of Alders (aka the city council), which, according to the New Haven Independent, in the face of catastrophic student performance data, spent much of its last meeting debating reading-instruction techniques even as 58 percent of the city's public school students are classified as chronically absent.

At least the meeting produced admissions from Supt. Ilene Tracy that for two years student mental health and "social-emotional learning" have displaced academic instruction and that student behavior is now "atrocious."

So it may not be surprising that the shortage of teachers, a national problem, is especially bad in New Haven's schools, which have about 300 unfilled positions amid a steady drain of teachers to school systems where salaries and students are better.

Of course while their political correctness doesn't help, New Haven's educators are mainly just playing the hand they have been dealt. They can't choose their students or the parents of their students.

But the disaster of education in New Haven and Connecticut's other cities has continued long enough that the Board of Alders, city legislators (including the influential New Haven Democrat Martin M. Looney, president pro tem of the state Senate), the state education bureaucracy, and Governor Lamont should have noticed by now that it is entirely a matter of demographics, the perpetual poverty arising from child neglect at home.

Instead these leaders keep clamoring for more programs to remediate the neglect rather than to address its cause and thereby prevent it -- and these programs keep failing spectacularly and expensively.

It is all an old of story of public education, documented in 1966 by the sociologist James S. Coleman, of Johns Hopkins University, who was assigned by the U.S. Office of Education to interpret the mass of school data collected at the direction of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Coleman's most important conclusion was recounted this month by the writer Ian V. Rowe in National Review magazine. Coleman wrote:

“One implication stands out above all: That schools bring little influence to bear on a child's achievement that is independent of his background and general social context; and that this very lack of an independent effect means that the inequalities imposed on children by their home, neighborhood, and peer environment are carried along to become the inequalities with which they confront adult life at the end of school.”

Coleman did not conclude that schools themselves don't matter at all. To the contrary, he found that disadvantaged children perform better in schools with better students, where standards are higher and peers set better examples. But that too was a matter of getting the children away from the bad influences of their home life.

In this respect the Coleman report echoed the findings of the report a year earlier by another sociologist, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who was then assistant U.S. labor secretary and who became a great U.S. senator. Moynihan blamed severe poverty and urban chaos on the breakdown of the family.

Indeed, the chronic absenteeism in New Haven's and other city school systems practically screams neglect of children by their parents, without even a whisper about teaching techniques.

If simply acknowledging the real problem in urban education in Connecticut is hard, it is harder still to imagine how politics would allow it to be addressed.

City officials and legislators cannot examine the causes of child neglect and educational failure without indicting their own constituents.

State officials can't examine the causes without indicting themselves for a welfare system that destroys the family while putting thousands of unionized and politically active "helpers" on the government payroll.

Educators, also numerous, unionized, and politically active, can't do it without calling more attention to their irrelevance and impugning their employment.

Academics like Coleman and Moynihan did it and some keep doing it, and journalism can call attention to their work. But if the trend toward illiteracy and ignorance keeps accelerating, there will be no one left to read it, much less act on it.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester. He can be reached at CPowell@JournalInquirer.com.

The delights of coastal debris

From “Coast,’’ a collection of smalll altered found objects and constructions, by Abbie Read, at Boston Sculptors Gallery, that recalls a natural history exhibit.

The gallery explains:

The exhibition pays homage to the artist’s strong connection to a particular place, the shoreline of Matinicus Island, in Maine, where Read’s family has had a home since the 1950s.

“Coast’’ emerged from a lifetime of collecting debris there. “Detritus from the shoreline, much of which consists of remnants of the fishing industry, has provided an ongoing inspiration for her artistic practice, finding its way into both two– and three– dimensional work. The exhibition also features a 100–page artist book of drawings.’’

Matinicus Harbor at low tide. Matinicus is the farthest out inhabited U.S. land off the East Coast.

— Photo by Jim Kuhn

Llewellyn King: We need much more nuclear power in the drive toward massive expansion of electrification

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A new day is breaking for the nuclear industry in the United States. There are four drivers of the new enthusiasm for nuclear power, which is being felt throughout the utility world.

First, nuclear is “dispatchable.” That is the term for the power you can rely on; power that will be there when you need it, and you can dispatch it.

At present, utilities are struggling with an overload of non-dispatchable power coming from wind and solar generation. That is available only when the wind blows or the sun shines. Fossil fuel and nuclear power are dispatchable — and highly regarded in the industry.

The Texas grid, known as Electric Reliability Council of Texas, was near catastrophe during the recent extreme heat wave when wind generation, which is a major part of the Texas power portfolio, simply wasn’t there to be dispatched. The ERCOT system has 35,391 megawatts of installed wind power; less than 1,000 megawatts of that were available.

Second, a new range of nuclear-power designs is making its way to market, and they have many advantages over the old, large plants of the kind that still produce 20 percent of the nation’s power, all of it dispatchable.

The new reactors, small modular reactors (SMRs), come in various sizes and use differing technologies from today’s jumbo workhorses — and they promise great things.

A panel of nuclear-power experts at a recent U.S. Energy Association virtual press briefing, which I organized and hosted, agreed that whether the technology is light water, molten salt or some other choice, SMRs will use less steel and concrete per unit of power produced, and they will require less land.

They have superior, failure-resistant fuel and will be passive, inherently safer, and won’t require their big brothers’ pumps and backup generators. Also, Bud Albright, president of the U.S. Nuclear Industry Council, told the media that these reactors will operate for 60 or more years and require fueling less frequently.

The SMRs come in various technologies and sizes, from NuScale’s 80-MW light water modules being built in Idaho to GE Hitachi Nuclear’s 300-MW reactor, the BWRX-300, being considered by the Tennessee Valley Authority. The modules will offer utilities flexibility in the size of the installation as well as enable individual modules to be repaired while the plant continues to produce power.

Cost remains an open issue. The USEA’s panel was quick to point out that factory manufacturing, standardization of design, and the simplicity of the new offerings would reduce their costs. But they weren’t so sure how these could go.

Jon Ball, executive vice president of GE Hitachi Nuclear, estimated that the BWRX-300 will deliver power at $60 a megawatt hour. That is still well above the cost of wind or solar power. So dispatchability and lifespan are important.

The third driver for a nuclear surge is the Inflation Reduction Act, which has put a new spring into the power generators’ steps. Doug True, vice president and chief nuclear officer of the Nuclear Energy Institute, said the act will level the playing field for nuclear compared to wind and solar.

Louis Finkel, vice president of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, told me he thinks there will be a surge in interest among rural co-ops to build reactors and that some that now are only in the distribution business will be interested in adding generation.

The Inflation Reduction Act makes this possible in several ways, but most important, it extends to not-for-profit utilities, like the co-ops and municipals, the benefits of construction and operating tax credits. These they will receive in the form of a check from the Treasury, which can be as much as 30 percent of the project.

Overall, driving the need for nuclear is that the nation needs more power if it continues its headlong rush to electrification of surface transportation and manufacturing.

The National Academy of Sciences predicts that electricity production will have to grow 170 percent between now and 2050. NRECA’s Finkel points out that the academy’s study doesn’t include coal and gas taken out of production to achieve net-zero emissions in the same timeframe

There would, indeed, seem to be a new day for nuclear.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

But the days grow short

“Summer” (oil on panel” by Philip Koch, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

The gallery reports:

“Philip Koch is well known for his colorful, panoramic landscapes. Less known is that he was originally an abstract artist. A pivotal event for him was seeing the work of Edward Hopper (1882-1967) It inspired him early in his career toward realism.

‘‘Koch has been given unprecedented access to Hopper’s studio on

Cape Cod, enjoying 19 residencies there since 1983, an honor granted

to no other living American artist.

‘‘He is an emeritus professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Koch’s grandfather was the inventor of the original Kodachrome color-

film process. Mr. Koch is also the great-grandson of John Wallace, the Scottish landscape painter.’’

Noble nectar

The Truro Vineyards in North Truro, Mass.

— Photo by Caliga10

"Behold the rain which descends from heaven upon our vineyards, and which incorporates itself with the grapes to be changed into wine; a constant proof that God loves us, and loves to see us happy."

— Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), American founding father, scientist, inventor and businessman. He grew up in Boston. Apparently, contrary to the old story, he never cited beer as proof that God loves us. We briefly fell into that error here.

In Maine, working on virtual reality and self-driving cars

Researcher with a virtual reality headset.

— Photo by ESA, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report

“Researchers at the University of Maine’s Virtual Environment and Multimodal Interaction Lab (VEMI) are working on cutting-edge technology to contribute to the development of self-driving cars and virtual reality. The VEMI lab recently won a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Inclusive Design Challenge for $300,000 to fund research for autonomous vehicles.

“The VEMI lab was founded by Dr. Rick Corey and Dr. Nick Giudice in 2008 with the idea of creating a space that students and faculty from different disciplines can come together to create technology-based solutions to global problems. With this new federal funding, VEMI lab scientists will create a ride-hailing app targeted at helping older adults and the visually impaired. The app would use electric cars that would be maintained at a central hub and use a payment system based on membership rather than a per ride. The autonomous vehicles would help older adults and people who are visually impaired access safe rides in such areas as rural Maine where access to public transportation or ride shares can be hard to find.

“Dr. Corey said, ‘[W]e don’t want to be constrained to the classroom or the traditional lab. We’re in the business of trying to make the world a slightly better place, and to break down the barriers between technology and people.’’’

At the University of Maine’s flagship campus, in Orono, on Marsh Island

— Photo by Jalnet2

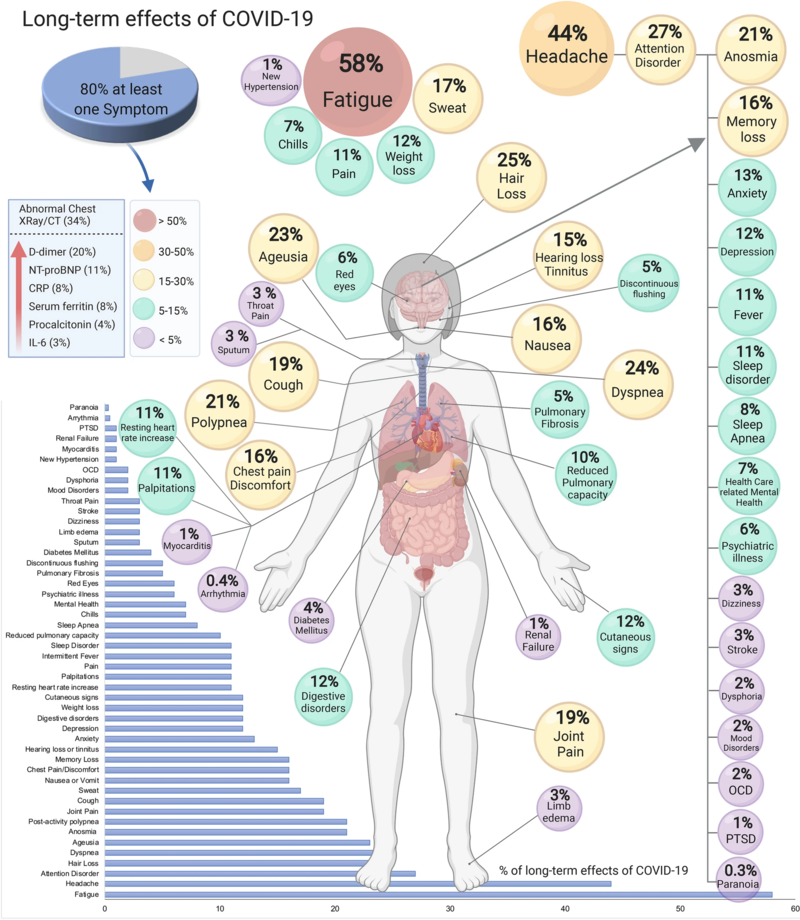

Liz Szabo: Looking at the Interplay of Omicron, reinfections and long COVID

“I suspect there will be millions of people who acquire long COVID after Omicron infection.”

— Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of immunobiology at Yale University.

The latest COVID-19 surge, caused by a shifting mix of quickly evolving omicron subvariants, appears to be waning, with cases and hospitalizations beginning to fall.

Like past COVID waves, this one will leave a lingering imprint in the form of long COVID, an ill-defined catchall term for a set of symptoms that can include debilitating fatigue, difficulty breathing, chest pain, and brain fog.

Although omicron infections are proving milder overall than those caused by last summer’s Delta variant, omicron has also proved capable of triggering long-term symptoms and organ damage. But whether omicron causes long covid symptoms as often — and as severe — as previous variants is a matter of heated study.

Michael Osterholm, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, is among the researchers who say the far greater number of Omicron infections compared with earlier variants signals the need to prepare for a significant boost in people with long covid. The U.S. has recorded nearly 38 million COVID infections so far this year, as Omicron has blanketed the nation. That’s about 40 percent of all infections reported since the start of the pandemic, according to the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Research Center.

Long COVID “is a parallel pandemic that most people aren’t even thinking about,” said Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of immunobiology at Yale University. “I suspect there will be millions of people who acquire long COVID after Omicron infection.”

Scientists have just begun to compare variants head to head, with varying results. While one recent study in The Lancet suggests that omicron is less likely to cause long COVID, another found the same rate of neurological problems after Omicron and Delta infections.

Estimates of the proportion of patients affected by long covid also vary, from 4 percent to 5 percent in triple-vaccinated adults to as many as 50 percent among the unvaccinated, based on differences in the populations studied. One reason for that broad range is that long COVID has been defined in widely varying ways in different studies, ranging from self-reported fogginess for a few months after infection to a dangerously impaired inability to regulate pulse and blood pressure that may last years.

Even at the low end of those estimates, the sheer number of omicron infections this year would swell long-covid caseloads. “That’s exactly what we did find in the U.K.,” said Claire Steves, a professor of aging and health at King’s College in London and author of the Lancet study, which found patients have been 24 to 50 percent less likely to develop long COVID during the Omicron wave than during the delta wave. “Even though the risk of long COVID is lower, because so many people have caught Omicron, the absolute numbers with long covid went up,” Steves said.

A recent study analyzing a patient database from the Veterans Health Administration found that reinfections dramatically increased the risk of serious health issues, even in people with mild symptoms. The study of more than 5.4 million V.A. patients, including more than 560,000 women, found that people reinfected with covid were twice as likely to die or have a heart attack as people infected only once. And they were far more likely to experience health problems of all kinds as of six months later, including trouble with their lungs, kidneys, and digestive system.

“We’re not saying a second infection is going to feel worse; we’re saying it adds to your risk,” said Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly, chief of research and education service at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System.

Researchers say the study, published online but not yet peer-reviewed, should be interpreted with caution. Some noted that VA patients have unique characteristics, and tend to be older men with high rates of chronic conditions that increase the risks for long covid. They warned that the study’s findings cannot be extrapolated to the general population, which is younger and healthier overall.

“We need to validate these findings with other studies,” said Dr. Harlan Krumholz, director of the Yale New Haven Hospital Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation. Still, he added, the V.A. study has some “disturbing implications.”

With an estimated 82 percent of Americans having been infected at least once with the coronavirus as of mid-July, most new cases now are reinfections, said Justin Lessler, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Of course, people’s risk of reinfection depends not just on their immune system, but also on the precautions they’re taking, such as masking, getting booster shots, and avoiding crowds.

After her second COVID-19 infection, Tee Hundley, a Jersey City, N.J., \ salon owner, says her lungs seemed damaged: “I felt like I was breathing through a straw.” More than a year later, the tightness in her chest remains. “I feel like that’s something that will always be left over,” Hundley says. “You may not feel terrible, but inside of your body there is a war going on.”

After her second infection, she returned to work as a cosmetologist at her salon but struggled with illness and shortness of breath for the next eight months, often feeling like she was “breathing through a straw.”

She was exhausted, and sometimes slow to find her words. While waxing a client’s eyebrows, “I would literally forget which eyebrow I was waxing,” Hundley said. “My brain was so slow.”

When she got a breakthrough infection in July, her symptoms were short-lived and milder: cough, runny nose, and fatigue. But the tightness in her chest remains.

“I feel like that’s something that will always be left over,” said Hundley, who warns friends with covid not to overexert. “You may not feel terrible, but inside of your body there is a war going on.”

Although each Omicron subvariant has different mutations, they’re similar enough that people infected with one, such as BA.2, have relatively good protection against newer versions of omicron, such as BA.5. People sickened by earlier variants are far more vulnerable to BA.5.

Several studies have found that vaccination reduces the risk of long COVID. But the measure of that protection varies by study, from as little as a 15 percent reduction in risk to a more than 50 percent decrease. A study published in July found the risk of long COVID dropped with each dose people received.

For now, the only surefire way to prevent long covid is to avoid getting sick. That’s no easy task as the virus mutates and Americans have largely stopped masking in public places. Current vaccines are great at preventing severe illness but do not prevent the virus from jumping from one person to the next. Scientists are working on next-generation vaccines — “variant-proof” shots that would work on any version of the virus, as well as nasal sprays that might actually prevent spread. If they succeed, that could dramatically curb new cases of long COVIDF.

“We need vaccines that reduce transmission,” Al-Aly said. “We need them yesterday.”

Liz Szabo is a Kaiser Health News correspondent.

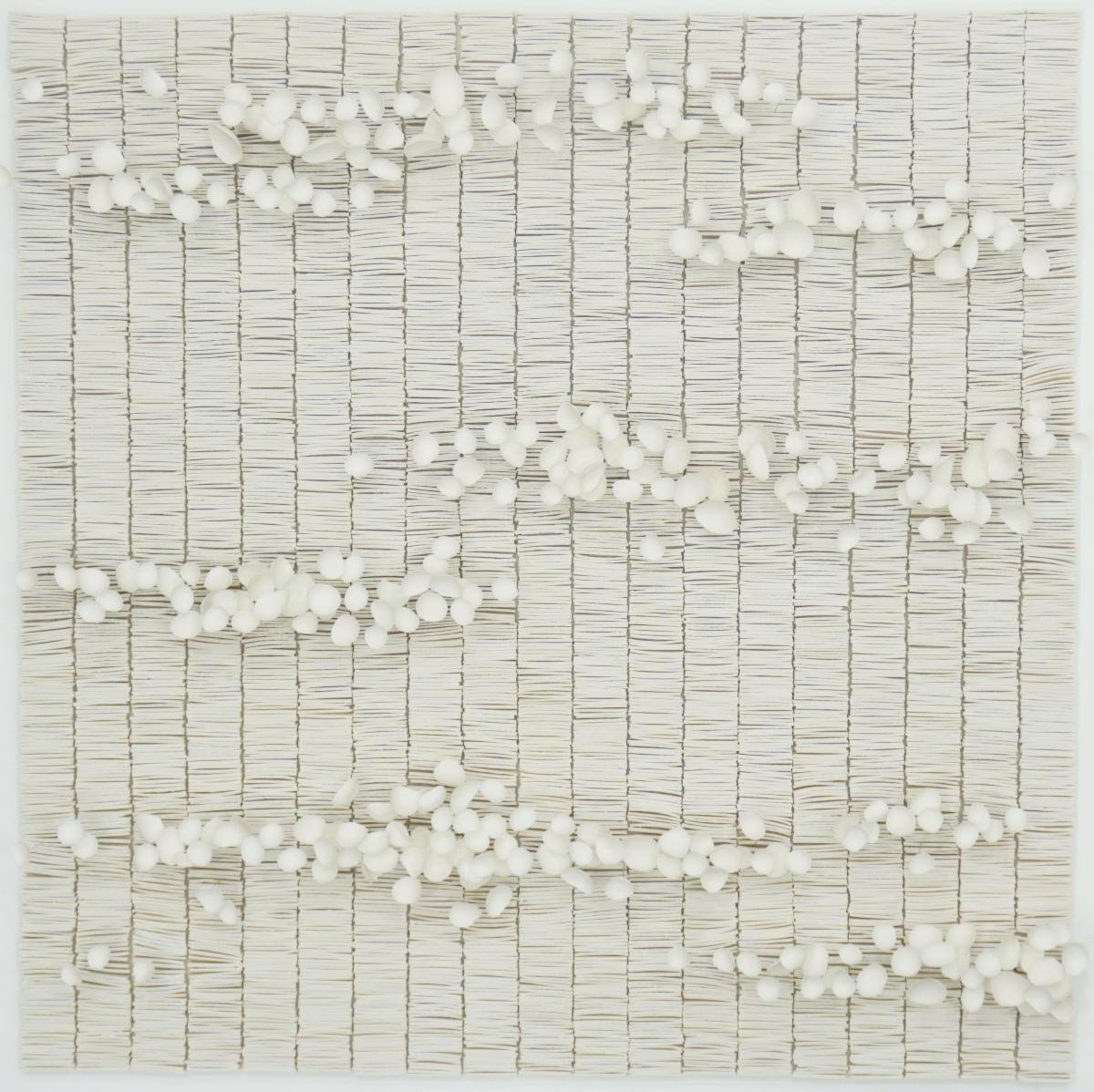

‘Celebration of irregularities’

“Resilience” (porcelain, wire on panel), by Lucas Ferreira, in the show “Ferreira & Nascimento: Natural Terrains,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., Aug. 27-Oct 8.

The gallery explains:

“This is the first exhibition for Lucas Ferreira in the United States. Born and raised in Brazil, Ferreira’s success as an artist came about serendipitously when he moved to London in his early twenties to study cinema. He began working in ceramic as a means to support his film projects in what he dubs is ‘a capricious industry.’ As he explored the properties of porcelain ceramic and developed his own techniques and language, Ferreira found the demand for his work exceeding his wildest expectations.

“For Ferreira, his work is a ‘celebration of irregularities’ that begins with small, simple shapes which are then repeated thousands of times. Ferreira works with porcelain ceramic in its purest form, rolling the material out into paper thin sheets and allowing it to dry for about an hour. This prevents the porcelain from sticking to the tools he utilizes to cut the individual shapes. Each piece is meticulously hand-cut and allowed to dry further before being fired in a high-powered kiln. As the tiles are assembled together in an organized fashion, the hand-made becomes more evident. Rather than getting uniformly lost in the grouping, the individual character of each piece is accentuated adding dimension to the overall textured surface. Color, derived from natural minerals, also plays a part in his work, as the pieces can go from lighter to darker values, or make a statement of form and perspective against neutral backgrounds. Ferreira’s process develops organically, the composition and rhythm dictated by spontaneous thoughts and feelings of the moment. The results are landscape tessellations, fragmented shapes that are visual feasts made timeless with the use of ancient mosaic techniques. Ferreira also credits as influence the work of Sérgio de Camargo, the Brazilian sculptor and relief maker who became an important figure in the Latin American Constructivist movement. Ferreira’s work has been the subject of many exhibitions in Europe and is in numerous private and corporate collections. His mosaic compositions are also in high demand for site-specific commissions. Ferreira currently lives and works in London.

“On view alongside Ferreira’s mosaics will be new work by gallery roster artist Valéria Nascimento. Her artistic practice shares certain aspects with Ferreira in that she too makes the porcelain material paper thin before hand-cutting each piece individually. As with Ferreira, the porcelain is left in its natural, unglazed finish, and only colored with oxides or minerals. The similarities end there, however, for her shapes are directly inspired by nature and take on the forms of stunning botanical or aquatic installations. Flora, blooms, hibiscus, bamboo, branches, or coral, anemones, and the like grace the spaces they inhabit. Nascimento’s architectural background informs her intricate and detailed presentation, and her work is about bringing nature indoors. The exhibition will feature a site-specific wall-mounted “meadow” installation as well as other work new to American audiences. Also included are works the two artists collaborated on, combining their distinctive aesthetics into three separate panels. Nascimento has had a prolific career and has been extensively exhibited and written about. Her work is in multiple private and public locations throughout the world.’'

The Glass House is a historic house museum on Ponus Ridge Road in New Canaan, built in 1948–49. It was designed by architect Philip Johnson (1906-2005) as his own residence.

‘Bostonitis’

Boston from above, with its famous harbor, the initial source of its power and wealth, in the middle.

“Then here's to the City of Boston,

The town of the cries and the groans,

Where the Cabots can't see the Kabotschniks

And the Lowells won't speak to the Cohns.’’

— Franklin Pierce Adams (1881-1960), New York columnist

"No doubt the Bostonian has always been noted for a certain chronic irritability — a sort of Bostonistis — which, in its primitive puritan form, seemed due to knowing too much of his neighbors, and thinking too much of himself.''

— Henry Adams (1838-1918), American historian and member of the famous Massachusetts Adams family

‘Tongue-rich smells’

— Photo by Gary Rogers

“Portsmouth Harbor, New Hampshire”, by William James Glackens (1909)

“I am built of the scent

of August marsh,

wishing well verdigris pennies,

the first turn of leaf-molded dirt.

Tongue-rich smells

permeate my fingertips,

behind knees, inside elbows.’’

— From “After — For Adam,’’ by Portsmouth, N.H.-based poet and librarian Lesley Kimball

Mass. promoting addiction; best place to live?

Odds boards in a Las Vegas facility

— Photo by Baishampayan Ghose

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Much of sports beyond the high-school level is becoming an adjunct of the huge sports-betting industry, which continues to create ever more gambling addicts. Massachusetts is doing its part to make things worse by now allowing – actually, encouraging -- sports betting in order to get more tax revenue – instant gratification on whatever electronic device you want.

The release of dopamine during gambling occurs in brain areas similar to those activated by taking certain widely abused drugs. Similar to drugs, repeated exposure to gambling and its associated uncertainty and anxiety, as well as its happy rush, produces lasting changes in the human brain.

Remember that betting is rife among poor people.

So state government will inevitably cause another increase in the social ills associated with addictive gambling – substance abuse, bankruptcies, embezzlements, etc.

Bettable?

A portion of the gorgeous Connecticut River Valley in South Deerfield, Mass.

— Photo by Tom Walsh

WalletHub has declared Massachusetts the best state to live in, based on affordability, the economy, education and health, quality of life and safety.

Rhode Island, a much poorer state, was way down at 28th, and Connecticut, with its troubled cities, a mediocre 25th. But New Hampshire was 6th, Maine was 11th and Vermont 12th. Those are known for their calm, civic-minded cultures and, yes, relatively homogeneous populations.

Interestingly, two other states with large urban populations and high taxes, like the Bay State, ranked high– New Jersey 2nd and New York 3rd.

The central factor: Good public services and the willingness to pay for them. The worst states to live in, as usual Trump cult states. Suckers!

But as always, take all such rankings with skepticism. Comparing apples with oranges, etc.

To read the whole list, hit this link.

Colleen Cronin: Paddling up the improving but still troubled Blackstone River

Usually the water comes up nearly to this fallen log in the Blackstone River, but due to drought conditions, passing under the tree was much easier.

— ecoRI News photo

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When Ed Oleksyk was growing up around the Blackstone River, he and his best friend would hike the river valley with absolutely nothing except their imaginations and ingenuity.

As they moved upriver on land, they picked up tires, pieces of plywood, metal poles, and whatever else they could find along the way — the Blackstone, called the birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution, was once more of a dumping ground than a recreational spot.

“The challenge was to ride whatever we put together” like Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer, Oleksyk said Aug. 12 as he prepared to paddle part of the river in Massachusetts from Grafton to Uxbridge in a canoe with his son Jack.

Ed and Jack Oleksyk joined a small group of travelers last week for a leg of the Blackstone River Commons Paddle, a four-day, 60-mile paddle through almost the entire historic waterway to bring attention to and advocate for the river’s preservation.

Traveling down the river from Worcester, Mass., to Narragansett Bay tells a story that’s harder to see from land, said Emily Vogler, an associate professor of landscape architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design and creator of the Blackstone River Commons, which hosted the paddle along with several other organizations.

The river’s complicated past, its recovery, and the precariousness of its future are on full display from the seat of a kayak drifting in its waters.

Because of drought conditions across Massachusetts and Rhode Island, the water table and the river are extremely low. Many parts of the river on which the group paddled Friday weren’t more than mid-shin deep.

This paddle is more of a workout for the abs than the arms, Vogler said, because when a kayak gets stuck in a shallow spot, some scooting is needed to get it floating again.

Even if the river was high, paddling in a group is about working as a team, offering advice on how to navigate safely and successfully under logs, around sharp turns, and even over land when dams and dry spots call for it.

“River right,” the elder Oleksyk called ahead of the rest of the group, telling us to move to the outer bend of the river, where it tends to be deeper. “You learn to read the river,” he advised a nervous ecoRI News reporter on her first river paddle.

Frank Cortesa, the president of Rhode Island Canoe & Kayak Association, which lent some of the boats for the paddle and provided ground support throughout, suggested looking for the “V” in the water to find the deepest point in a passage and leaning into obstacles rather than away to avoid tipping over.

While the low river conditions made paddling difficult at points, it also made it easier to float down “rapids” and reduced the dangerousness of strainers — low hanging or downed trees and branches that can catch boats and people on higher water and faster conditions, Cortesa said.

The low water level also reveals things long hidden.

Paddling past an old junkyard Vogler pointed to the exposed riverbed, layered with different types of debris, from sheets of metal to the innards of a bicycle tire.

Though some of the tires and debris along the river looked old and decayed, some of the tires and other trash in the river were new.

By end of the second day of paddling, the group had spotted more than 100 tires in and around the water. They also spotted a few bicycles, a kiddie pool, an abandoned kayak, the bed of a truck, the chassis of a car, and several traffic cones, among other smaller debris.

That kind of litter is sprinkled through the Blackstone River watershed today, but it was much worse years ago, before serious efforts to clean up the river and toughen environmental regulations began. A river cleanup is scheduled for Aug. 27, the 50-year anniversary of the massive 1972 cleanup called ZAP the Blackstone.

After the colonization and industrialization of North America and before the Clean Water Act, the Blackstone River was a place where people dumped their trash and companies left their waste.

The river fed Slater Mill, in Pawtucket, which was the first water-powered textile mill in America and where the Industrial Revolution began.

Slater was the first of many mills to crop up on the river’s banks and then leak or drain chemicals into the water; locals would say the river changed color based on the dyes being used by the fabric manufacturers each day.

Old mill and wooden dam along the Blackstone in Grafton, Mass.

— ecoRI News photo

Dams from the mills, some of which are still used today, remain scattered along the river and required the group to portage their boats over land to continue the journey. The dams not only slow down the paddlers, they also stop fish moving freely from the river into the ocean and back in lower parts of the Blackstone. But dam removal is tricky and expensive, because the structures hold back toxic sediment build-ups left behind from the industrial era, which would wreak havoc on the environments downstream.

People used to be — and sometimes still are — afraid to interact with the river.

Donna Williams, a watershed advocate for and board president of the Blackstone River Coalition, said her husband used to tell the story of someone they knew who had let their dog swim in the river in the 1970s, after which the dog got sick and died.

“That was terrible. But that was when the river was terrible,” Williams said.

Now, Williams and her husband let their dog swim in the Blackstone and he only “smells just a little worse than he did before he went in.”

The water quality has improved significantly since the ‘70s and even since the early 2000s, Williams said. She was one of the organizers of Expedition 2000, the event that the Blackstone River Commons Paddle was loosely based on. (Williams did attend the land events surrounding the paddle but didn’t hop in this time around. “I’m getting older, so I haven’t been on the river lately,” she said).

Some of the river improvements were spurred by that original paddle, Williams said, which inspired people to get involved in watershed advocacy.

Still, the signs of prior and present harm crop up frequently along the Blackstone. The crew rode over and under old sewage lines on Friday, a reminder of several serious effluent leaks early this year that caused the river to become temporarily untouchable.

A group fishing on the riverbanks warned the paddlers about the potential for spills.

But the history and the industrial tints that give the Blackstone a bad reputation can often be forgotten while floating under the green canopy of the trees along the river.

Many creatures live in or near the Blackstone, including a blue heron that swept over the heads of the paddlers to a family of ducks that spooked an ecoRI News reporter when she got a little too close to their nest, setting off lots of flapping and quacking on an otherwise quiet stretch of river.

Nature’s engineers have also made a home on the Blackstone, with beaver dams lining the river. One beaver’s tail was spotted flitting under the water during Friday’s run.

The group also purposely ran themselves aground to stop and admire an eagle perched high above the river.

“Jack and I have hiked a lot of trails,” said Ed Oleksyk, rounding a small island filled with green herons (a smaller cousin of the blue they had seen earlier), “but there’s more wildlife on the river itself.”

Many more people are beginning to appreciate the beauty of the river.

“The number of businesses that now have the word Blackstone in their name has … increased like 100-fold,” Williams said. “People were kind of embarrassed to say they lived in the Blackstone Valley, but all of this activity has just brought a tremendous sense of pride.”

The goal of the paddle was to highlight past accomplishments and the beauty of the river, while also reminding the community of what more can be done.

The paddle was partly inspired by the publication of the Blackstone River Watershed Needs Assessment last year by the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program. The report, made in collaboration with dozens of groups during the pandemic, made recommendations for how to improve the river so that it could be a better resource for people and wildlife.

In the time since the assessment came out, some progress has been made. It already prompted the creation of the Blackstone Watershed Collaborative and the hiring of Stefanie Covino as its coordinator. She participated in the full 60-mile paddle.

Some of the report’s suggestions included creating a green jobs program, developing a wetlands restoration strategy, increasing fish access, and opening access to the river equitably.

The report also outlined how to offset some of the effects of climate change, which threaten the river, its inhabitants, and the people who rely on the watershed for an important and currently scarce resource: water.

“I’ve never seen it like this,” Oleksyk said as he struggled through parts of the river that were so dry that for hundreds of feet the paddlers dragged their boats from shallow pool to shallow pool.

Covino, who decided to take a snack break before getting out of her kayak for the fifth or sixth time to drag her boat over land, noted that all the water, or lack of water, in the region was connected.

The Blackstone River is a part of a watershed covering almost 550 square miles and encompassing thousands of lakes, other rivers, ponds, reservoirs, and personal wells.

As another tributary and canal drained into the Blackstone, eventually the water rose, and the group was able to finish the paddle actually paddling in Uxbridge to join the RiverFest planned for the afternoon.

The four-day event ended with a public paddle to the Narragansett Bay that brought in 60 attendees and a celebration at Narragansett Brewery.

Colleen Cronin is a Report for America corps member who writes about environmental issues in rural Rhode Island for ecoRI News.