Some love hurricanes

Storm surge in eastern Connecticut during Hurricane Carol, on Aug. 31, 1954.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

The hype about Tropical Storm Henri was extreme, even by New England storm standards. After all, Henri, at its height offshore as a minimal hurricane, had lighter winds than many winter Nor’easters that hit us.

But then, many people enjoy the hype and indeed like hurricanes, as long as their property isn’t damaged, and they get their electric power back within a day or two, which they usually do. Storms take people out of themselves by putting on a diverting show. And they jazz up late summer, when many people are tiring of the season, especially this year with its months of steamy weather. (How do people live in Florida year round?)

Hurricane Carol (Aug. 31, 1954), quickly followed by Hurricane Edna (Sept. 11, 1954) left many New Englanders without juice for up to two weeks. These days, utilities pump up an oncoming storm to ensure that they get timely help from utilities outside the region and that they won’t be blamed in those rare cases in which a storm turns out to be worse than forecast, such as last year’s Tropical Storm Isaias in Connecticut.

My most vivid memory as a boy of hurricanes, besides watching a couple of trees being uprooted, is the sweet smell of Sterno, which we used for cooking after the power went out.

Those Unsightly Lines

At India Point Park, Providence. Note power lines.

— Photo by Tim Burling

People in Providence’s Fox Point neighborhood, at the head of Narragansett Bay (or the head of the Providence River, if you prefer) who have fought for almost 20 years to get the utility lines from India Point Park to East Providence buried must have felt a pang when they read in GoLocal”

“The Scenic Aquidneck Coalition has announced the completion of a project to bury power and communication lines along Third Beach Road and Indian Avenue in Middletown, Rhode Island. Inspired by the 2017 Second Beach project, the Scenic Third Beach Project removes the rest of the poles on Sachuest Point along Third Beach and up Indian Avenue, promoting ‘coastal resiliency, restoring the historic landscape and enhancing the area’s scenic appeal.’’’

But the Middletown project only cost $4 million and was entirely paid with private donations. (There are plenty of rich individuals and organizations on Aquidneck Island.) The price of burying the Fox Point lines has risen to $33.9 million, and it remains uncertain how the cost would be shared among Providence and East Providence property-taxpayers and statewide electricity rate payers and taxpayers and National Grid – or other permutations and combinations.

I suspect that a big hurricane that takes out power for a long time would work wonders in getting those lines buried. Never waste a crisis.

Resurgent feminist art

“People Have Anxiety about Ambiguity” (collage), by Liza Basso, in the group show “Re Sisters: Speaking Up; Speaking Out ,’’ at Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass., Sept. 9-Oct 10.

The gallery says:

“The current political climate has put women’s rights and civil rights at risk. This exhibition is meant to bring attention to the recent resurgence in feminist art and its connection to activism and politics, as women face rollbacks in reproductive rights, the disproportionate effects of Covid 19, and a year that saw more women elected to political office than ever before. Through collections that delve into histories that are political, personal, and shared, ReSisters explores the experiences of women in a post-trump era.’’

Dana Brown: Consider option of having the public own firms making generic drugs

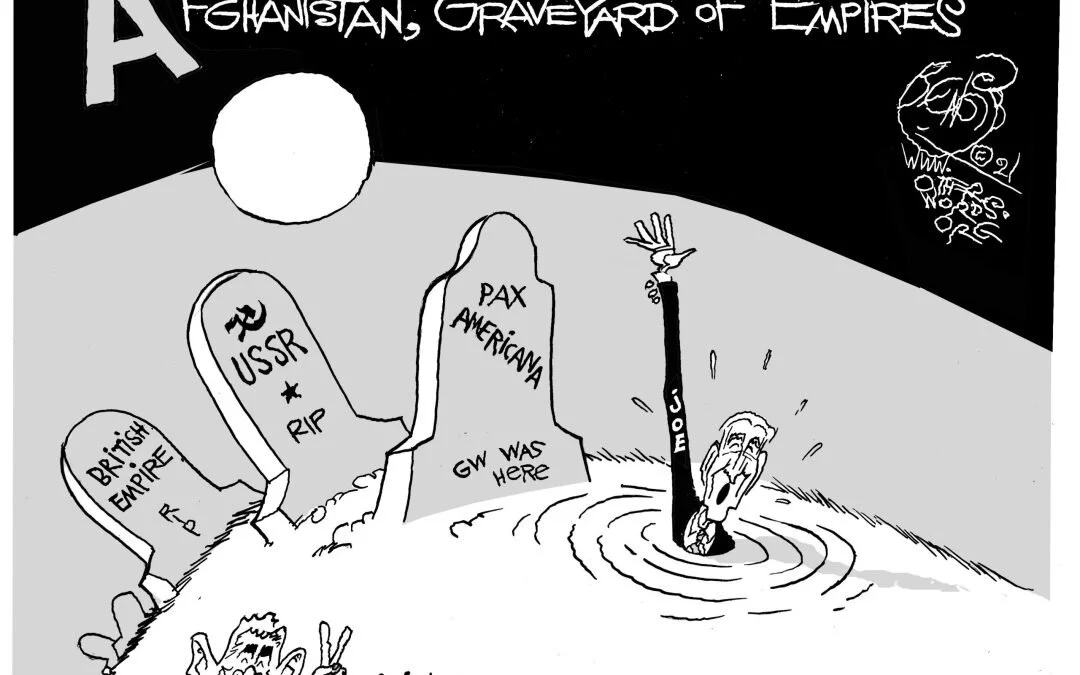

Via OtherWords.org

It’s an all too familiar story. A company with some of the best-paying jobs around and a vital anchor for the community decides to engage in “restructuring” to “maximize long-term value creation.”

In other words, it closes down and lays off its workers in pursuit of bigger profits.

But the late July closure of the Viatris pharmaceutical plant in Morgantown, W.Va. — which employed close to 1,500 people and was the largest remaining generic-medications plant in the U.S. — is particularly galling. [There are several generic-drug companies in New England.}

West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice echoed a sentiment shared across the political spectrum when he said on August 4, “I think it’s pitiful, pitiful, absolutely pitiful that our federal government at this time, with something as critical as pharmaceuticals are to our citizens, is just deciding to sit on the sideline and let this catastrophe happen.”

The closing was uniquely preventable — if there had been federal or state action premised on prioritizing protecting public health and economic wellbeing over short-term shareholder returns. We had the tools. All that was lacking was the boldness and the political will to use them.

The chain of events started in 2020 when the plant’s then-owner, Mylan (run by Heather Bresch, West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin’s daughter), merged with Upjohn to form a new company, Viatris, creating the largest generics company in the world. Not long after, Viatris announced a “restructuring initiative” that included shuttering some of its plants, including the Morgantown facility.

The Steelworkers local representing many of the plant’s workers began petitioning both the incoming Biden administration and state officials to keep the plant open. Their key argument was its role in the country’s pharmaceutical supply chain, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The plant produced 18 billion doses of low-cost generics a year — including many essential medicines paid for through various federal programs.

A letter to the Biden administration signed by the Steelworkers and about 40 other health-care and advocacy groups (including The Democracy Collaborative, where I work) called for using the Defense Production Act to stop the closure of the plant.

One of President Biden’s first executive orders called for using the law if necessary for “acquiring additional stockpiles, improving distribution systems, building market capacity, or expanding the industrial base.” But the Biden administration, like the Trump administration before it, did none of these things in Morgantown.

Keeping the Morgantown plant open would have been a clear case of assuring local distribution and manufacturing capacity for an essential good: medicine. The designation that the plant already has from the Department of Homeland Security as critical infrastructure underscores that.

Overlooked was the opportunity to explore a public-ownership option in pharmaceuticals. Public enterprises are free from profit constraints and can instead define their bottom line based on what they contribute to public health, scientific advancement, and local economic resiliency.

The gains for our communities would be massive: Reliable access to affordable generics helps keep people out of hospitals and in jobs, schools, and community service roles. Generics dramatically reduce our overall health care costs. Plus, the manufacturing plants are vital economic engines as well as hubs of home-grown intellectual capital.

It is encouraging that a public institution, West Virginia University, announced talks with Viatris to acquire the plant, but that was after hundreds of highly skilled workers were needlessly laid off, most of whom cannot wait to see if a deal is struck before looking for new jobs.

What we really need in the face of continued outsourcing and offshoring is a real industrial strategy that includes public ownership — and puts community health above the demands of absentee shareholders.

Dana Brown is director of The Next System Project at The Democracy Collaborative, “a research and development lab for the democratic economy.”

David Warsh: Time to read ‘Three Days at Camp David’

The main lodge at Camp David

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The heart-wrenching pandemonium in Kabul coincided with the seeming tranquility of the annual central banking symposium at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. For the second year in a row, central bankers stayed home, amid fears of the resurgent coronavirus. Newspapers ran file photos of Fed officials strolling beside Jackson Lake.

Market participants are preoccupied with timing of the taper, the Fed’s plan to reduce its current high level of asset purchases. That is not beside the point, but neither is it the most important decision facing the Biden administration with respect to the conduct of economic policy. Whom to nominate to head the Federal Reserve Board for the next four years? For a glimpse of the background to that question, a good place to start is a paper from a a Bank of England workshop earlier in the summer

Central Bank Digital Currency in Historical Perspective: Another Crossroads in Monetary History, by Michael Bordo, of Rutgers University and the Hoover Institution, brings to mind the timeless advice of Yogi Berra: when you come to a crossroad, take it.

Bordo briefly surveys the history of money and banking. Gold, silver and copper coinage (and paper money in China) can be traced back over two millennia, he notes, but three key transformations can be identified in the five hundred years since Neapolitan banks began experimenting with paper money.

First, fiduciary money took hold in the 18th Century, paper notes issued by banks and ostensibly convertible into precious metal (specie) held in reserve by the banks. Fractional banking emerged, meaning that banks kept only as much specie in the till as they considered necessary to meet the ordinary ebb and flow of demands for redemption, leaving them vulnerable to periodic panics or “runs.” Occasional experiments with fiat money, issued by governments to pay for wars, but irredeemable for specie, generally proved spectacularly unsuccessful, Bordo says (American Continentals, French assignats).

Second, the checkered history of competing banks and their volatile currencies, led, over the course of a century, to bank supervision and monopolies on national currencies, overseen by central banks and national treasuries.

Third, over the course of the 17th to the 20th centuries, central banks evolved to take on additional responsibilities: marketing government debt; establishing payment systems; pursuing financial stability (and serving as lenders of last resort when necessary to halt panics); and maintaining a stable value of money. For a time, the gold standard made this last task relatively simple: to preserve the purchasing power of money, maintain a fixed price of gold. But as gold convertibly became ever-harder to manage, nations retreated from their fiduciary monetary systems in fits and starts. In 1971, they abandoned them altogether in favor of fiat money. It took about 20 years to devise central banking techniques with which to seek maintain stable purchasing power.

As it happens, the decision-making at the last fork in the road of the international currency and monetary system is laid out with great clarity and charm in a new book by Jeffrey Garten, Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy (2021, Harper) Garten spent a decade in government before moving to Wall Street. In 2006 he returned to strategic consulting in Washington, after about 20 years at Yale’s School of Management, ten of them as dean.

The special advantage of his book is how Garten brings to life the six major players at the Camp David meeting, Aug. 13-15, 1971 – Richard Nixon, John Connally, Paul Volcker, Arthur Burns, George Shultz, Peter Peterson and two supporting actors, Paul McCracken an Henry Kissinger – and explores their stated aims and private motives. The decision they took was momentous: to unilaterally quit the Bretton Woods system, to go off the gold standard, once and for all. It was a transition the United States had to make, Garten argues, and in this sense bears a resemblance to Afghanistan and the present day:

A bridge from the first quarter-century following [World War II] –where the focus was on rebuilding national economies that had been destroyed and on re-establishing a functional world economic system – to a new emvironment where power and responsibility among the allies had to be readjusted . with the burden on the United States being more equitably shared and with the need for multilateral cooperation to replace Washington’s unilateral dictates.

What about Nixon’s re-election campaign in 1972? Of course that had something to do with it; politics always has something to do with policy, Garten says. But one way or another, something had to be done to relieve pressure on the dollar. “The gold just wasn’t there” to continue, writes Garten.

The trouble is, as with all history, that was fifty years ago. What’s going on now?

Read, if you dare, the second half of Michael Bordo’s paper, for a concise summary of the money and banking issues we face. Their unfamiliarity is forbidding; their intricacy is great. The advantages of a digital system may be manifest. “Just as the history of multiple competing currencies led to central bank provision of currency,” Bordo writes, “ the present day rise of cryptocurrencies and stable coins suggests the outcome may also be a process of consolidation towards a central bank digital currency.”

But the choices that central bankers and their constituencies must make are thorny. Wholesale or retail? Tokens or distributed ledger accounts? Lodged in central banks or private institutions? Considerable work is underway, Bordo says, at the Bank of England, Sweden’s Riksbank, the Bank of Canada, the Bank for International Settlements, and the International Monetary Fund, but whatever research the Fed has undertaken, “not much of it has seen the light of day.”

Who best to help shepherd this new world into existence? The choice for the U.S. seems to be between reappointing Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, 68, to a second term, beginning in February, or nominating a Fed governor Lael Brainard, 59, to replace him. President Biden is reeling at the moment. I am no expert, but my hunch is that preferring Brainard to Powell is the better option overall, for both practical and political ends. After all, what infrastructure is more fundamental to a nation’s well-being than its place in the global system of money and banking?

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

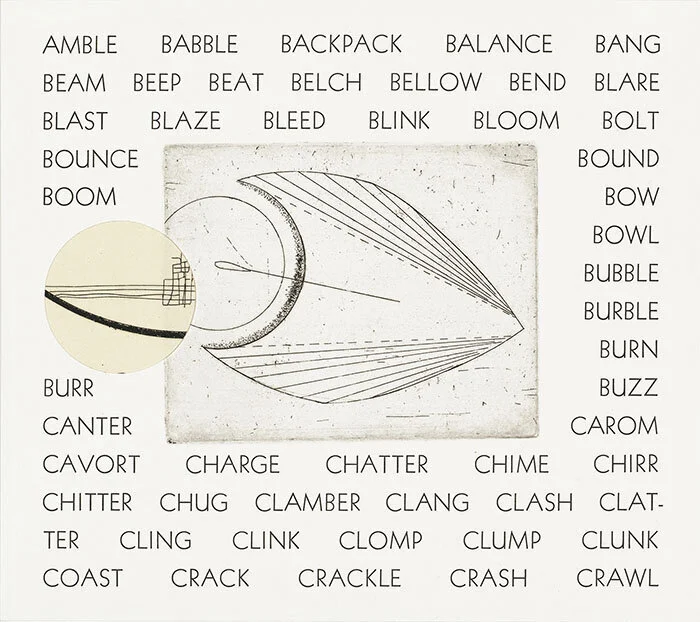

Language structures

“Figures of Speech” ((detail), etching and letterpress), by Somerville, Mass.-based Sarah Hulsey, in her show “Lexical Geometry,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Sept. 29-Oct. 31.

The gallery says:

“Sarah Hulsey's work portrays the patterns and structures that comprise our universal instinct for language. In this body of work, she uses schematic forms and letterpress text to explore connections across the lexicon.’’

The warm side of the river

“Great Falls’’ in Bellows Falls, Vt. at high flow under the Vilas Bridge, taken from the end of Bridge St on the Vermont side, looking upriver.

“{A} Connecticut River Valley farmer …. was told that his farm was really in New Hampshire, instead of Vermont as he’d always thought. ‘Thank God,’ he said. ‘I didn’t I could stand another one of those Vermont winters.’’’

— Evan Hill (1919-2010) in The Connecticut River (1972)

Chris Powell: Censorship undermines faith in medical science

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Science is wonderful. But it is not always settled. Sometimes the prevailing view in science is wrong, especially in medicine.

For 2,000 years a primary treatment for disease was bloodletting, sometimes administered with leeches. Doctors don't do that anymore.

A sedative called thalidomide was approved for use in European and other countries in the 1960s before it was found to cause birth defects.

The painkiller OxyContin, about which federal litigation is raging because of its highly addictive and even deadly properties, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1995. A year later an FDA official involved in OxyContin's approval was hired for a six-figure job at the drug's manufacturer, Stamford-based Purdue Pharma. Now the drug is blamed for thousands of deaths.

Medical mistakes are considered the third leading cause of death in the United States.

This week it was reported that the Food and Drug Administration had given full, formal approval to the Pfizer vaccine for the COVID-19 virus. But the FDA seems just to have extended the vaccine's authorization for emergency use.

Whereupon the acting commissioner of Connecticut's Public Health Department, Dr. Deidre Gifford, urged state residents to "trust the science" and get vaccinated.

It would have been fair to ask the commissioner: Whose science, exactly?

Of course, the commissioner wants people to follow the government's science. But there is other science, though it is increasingly subject to censorship by Internet sites and social media under government pressure.

Yes, quacks and cranks infiltrate discussion of the virus epidemic, as they always have infiltrated medicine. But the discussion also includes many highly credentialed doctors and scientists who -- at least before they voiced objections and concerns -- were renowned and honored in their fields. Some dispute the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines, while others dispute the vaccines' necessity, arguing that effective treatments for the virus are available.

These doctors and scientists could be mistaken. But censorship isn't how contrary assertions should be handled. Contrary assertions should be rebutted and learned from in the open.

This isn't happening because government, its allied medical authorities, and, it seems, journalism don't want a debate that might interfere with their preferred policy, vaccination. They are convinced that they have nothing to learn from the dissenters.

But the public isn't convinced. Many people are indifferent or even opposed to COVID-19 vaccination, and the policy advocated by many in government and the medical establishment is to stop trying to persuade people and start coercing them by denying them the right to live ordinary lives if they don't get vaccinated.

Much indifference and much opposition to vaccination are grounded in ignorance and contrariness. But not all.

Anyone paying attention to developments can perceive fair questions. For example, in regard to the Pfizer vaccine particularly, why is the government pushing it when it is still being tested and side-effects are still being discovered? Is this "approval" really a matter of safety or just political necessity?

And why is Israel's epidemic worsening, with a new wave of virus cases exploding to the level of the country's first wave even though Israel's population now may be the world's most thoroughly vaccinated -- primarily with the Pfizer vaccine?

The more what is said to be science relies on censorship and coercion, the less trust it will deserve.

Taliban religious police beating a woman in Kabul on Aug. 26, 2001.

- Photo by RAWA

If the thousands of Afghans who have swarmed the airport in Kabul for airlift out of the country really think that their country's new Taliban regime will be so terrible, where were they a few weeks ago when the U.S. military began withdrawing from the country?

Why did those thousands not enlist in the Afghan army in defense of the less totalitarian culture the U.S.-assisted government supported?

Those thousands might have formed a few useful military divisions, just as throughout history civilians were mobilized to defend cities under siege. Since women will be oppressed by the Taliban again, where was the Afghan army's 1st Women's Infantry Division? And how will Afghanistan's prospects be improved by removing so many people who oppose theocratic fascism?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

I'll still be here

Witchgrass

“….I was here first,

before you were here, before

you ever planted a garden.

And I’ll be here when only the sun and the moon

are left, and the sea, and the wide field.

I will constitute the field.’’

—From “Witchgrass,’’ by Louise Gluck (born in 1943), Nobel Prize winning New England poet and writer in residence at Yale

Homogeneous spirit

Above the tree line on the Presidential Range

— Photo by Fredlyfish4

“Though the landscape of New England presents the sharpest of contrasts, from gentle meadow and forest land to the rugged 5,000-foot peaks of the Presidential Range in New Hampshire, there is a kind of homogeneity about the whole that is a matter of spirit rather than of the land itself. If you love New England some inner sense will tell you when you are there.’’

— Stewart Beach (1900-1979) in New England in Color

Chase opens first ‘community center’ in New England

"Rise," a pair of statues installed in 2005, flank Blue Hill Avenue in Mattapan and define it as a gateway to Boston. The statue above is by Fern Cunningham. The one below is by Karen Eutemy.

Jon Chesto, of The Boston Globe, reports:

“Chase has opened the doors to its first ‘Community Center,’ in New England, in Mattapan Square. The retail arm of JPMorgan Chase & Co. is planning these community centers in 16 urban neighborhoods across the country, with 10 such centers opening so far. They provide traditional branch banking services, along with other community services. In the case of the Mattapan branch, Chase regional director Roxann Cooke said Chase has reached out to local nonprofits to help offer financial seminars and workshops at the branch for nearby residents and small-business owners.’’

Memory and geography

“At the Beginning” (cardboard, hand-cut world map), by Vivianne Rombaldi Seppey, in the group show “A Sense of Place,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., through Sept. 29. The show features new works by Tegan Brozyna Roberts, Simona Prives and Viviane Rombaldi Seppey.

The gallery says:

“Memory, geography and cultural experiences are underlying themes explored by these three women artists. Through an innovative use of paper, maps, threads, printmaking, collage and projected imagery, the artists in the show create two and three-dimensional objects that express universal notions of belonging and association.’’

Moreno Clock on Elm Street where it meets with South Avenue in New Canaan.

Almost hypnotized by boxwood

Common boxwood

“I have heard New Englanders say that they have an affinity for Box {wood) — that it exerts power like a hereditary memory, and affects them with an almost hypnotic force. This is not felt by everyone, but only by those who have loved Box for centuries, in the persons of their ancestors.’’

— Eleanor Early (1895-1969), in A New England Sampler (1940)

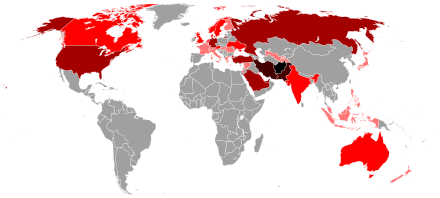

Llewellyn King: Future exports of the Taliban-run Afghanistan will include terrorists, migrants and heroin

The Afghan diaspora. The darker the color, the more Afghans.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The end of empire is not pretty. Or as Neil Sedaka sang, “Breaking up is hard to do.” The terrible scenes at Kabul’s airport attest to that -- as did those, 46 years earlier, in Saigon.

Technically, the United States has never had an empire nor sought one, but we have sent troops far and wide. Like other empires, bringing them home has been difficult, ugly, and made endless by refugees. Empire, or the American equivalent, follows you home.

The British, the French and the Russians have found the end of empire hard. As did the Romans in their day. Getting out has been a lot harder and uglier than getting in.

When the British withdrew from the Indian Subcontinent, leaving behind a new nation, called Pakistan, and an old one, called India, the blood flowed freely. The sectarian slaughter then was to lead to wars and skirmishes that have lasted to this day. Improbably, Pakistan was two separate entities, East and West Pakistan. Later, East Pakistan split off and became Bangladesh.

When Lord Mountbatten, a stiff-necked British public servant and a royal, set in motion the withdrawal, he ignored plentiful intelligence that there would be strife. An alternative plan called for a slow, measured withdrawal. Mountbatten decided that if it were to be done, it should be done quickly, and the result was more than 1 million died and 15 million to 20 million were displaced, as Muslims fled to Pakistan and Sikhs and Hindus in the opposite direction.

The French withdrew from Algeria and nearly sparked a civil war in France itself. When President Charles de Gaulle announced that France would withdraw from Algeria, there was uncertainty as to which way the French generals would go; reluctantly, they stuck with de Gaulle.

Algeria was truly part of France and the decision to leave was a bitter one. Many French citizens, called Pied-Noirs, like the writer and philosopher Albert Camus, had been born in Algeria, and regarded it as a part of France. But de Gaulle stood firm and civil war was averted -- just.

The worst colonial withdrawal -- it is generally agreed -- was the graceless Belgian exit from the Congo in 1960. Unlike the many former British colonies that inherited a political structure, complete with a parliamentary system based on the one in London, and English Common Law, the Belgians didn’t leave behind a viable political or legal structure for the Congolese.

Simply packing up and coming home is never enough. The French withdrawal from Algeria began an endless immigration stream into France. The British withdrawal from India and the country they created, Pakistan, paved the way for a flood of migrants into the United Kingdom. That isn’t over, as relatives and relatives of relatives claim the right to join family.

Resettled Afghans will bring with them their culture and, more important, their religion. They will leave their mark wherever they are resettled.

The present and future of Afghanistan is made more complex because with the U.S. withdrawal, a religion cloaked in nationalism is the victor. There are many devout Muslim-majority countries, but Afghanistan under the Taliban, will be the most complete. The dominance of religion as the national purpose will be established. The only legal system will be Sharia. And if history is a guide, it will be an extreme and intolerant version that will rule the 39 million people of Afghanistan.

Communism defeated capitalism in Vietnam. But in short order, communism was defeated there, and Vietnam became friendly to the United States, and as passionate about business as Singapore or Hong Kong.

There are no expectations for Afghanistan. A mountainous country of about 38 million people riled by tribalism, it will resume the export of the three things nobody wants: Heroin (opium poppies are a traditional crop), migrants and terrorism.

The debacle that has played out with our national humiliation on television won’t, alas, bring an end. It is, in its own way, a beginning.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Asking New England fishermen to do the right thing

Fishing boats in New Bedford, America’s biggest fishing port

Mario Batali (born 1960)) scandal-rich chef, businessman and writer

Loyally provincial

Juniper Point (once called Butler’s Point), in Woods Hole. The tower room of the house built by Daniel Webster Butler sticks out through the trees at center right.

— Photo by ToddC4176

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I had a great-great grandfather named Daniel Webster Butler (1838-1907) who, after making quite a bit of money as a manufacturer in Boston from about 1860 to 1880, retired to his native Falmouth, Mass., and built a big house (which is still there) in its village of Woods Hole. He filled it with nice stuff. A cousin of my father asked Mr. Butler’s daughter Virginia: “Did Grampa Dan {as he was called in the family} travel all over the Orient to get all these beautiful objects and furnishings?’’

“Heavens no,’’ she answered. “He would never leave Woods Hole.’’

(But he might have enjoyed traveling by the World Wide Web, whose founder, Timothy Berners Lee, was married for a while to a Butler descendant.)

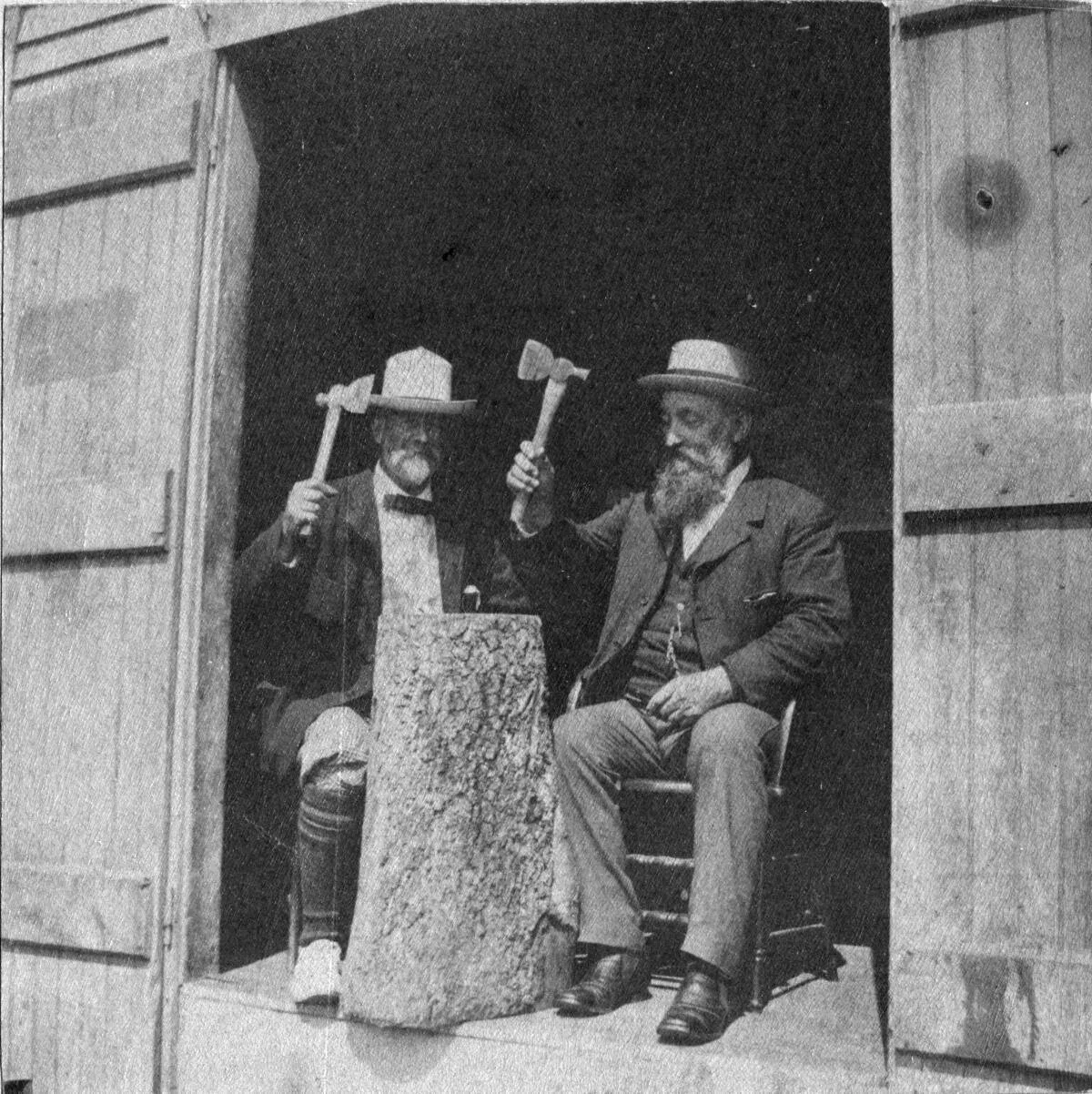

Dan Butler (left) with friend at the Pickwick Club

Dan Butler was also well known in the village for membership in the “exclusive’’ Pickwick Club that as far as can be determined, had no more than three members and met in an old fishing shack.

Steel BBs

How to Lose an Eye

BB guns are not toys. Getting hit by a BB in the eyes can permanently blind you. Consider that as you follow this maddening Providence police story, whose latest iteration can be seen in GoLocalProv.com.

I remember the stupid BB gun fights in the woods of my hometown by 12-year-old boys in the ‘50s. I assume that their parents actually bought them!

Weekend Training

The MBTA is maintaining surprisingly good Providence-Boston weekend train service despite COVID. Use it when you can, say to go to games, shows or plays. I do. Car traffic is intensifying again.

They usually are

“Disturbed Interactions” (acrylic on canvas), by Pat Paxson, in the group show “The Momentary,’’ at Fountain Street Fine Art, Boston, through Aug. 29.

She tells the gallery (mysteriously…):

"‘Function of time’ for me is: imaginary in terms of temporal possibilities in outer space, related to our uncontrolled release of physical and experimental sounds and images. ‘Time’ for me functions by way of imagination as well as articles in newspapers and results of experimental painting.’’

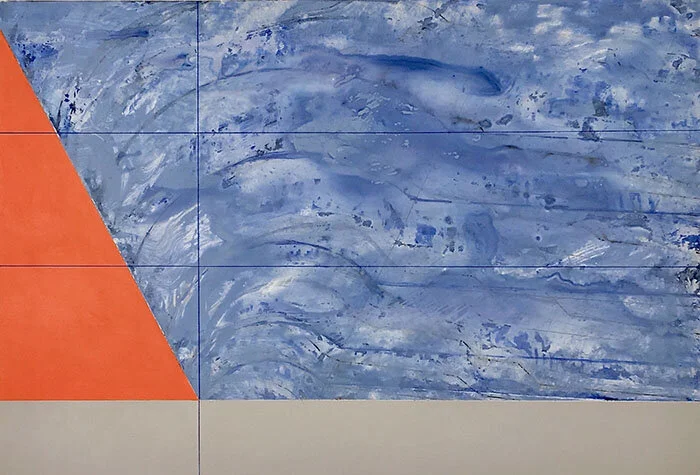

Looking at 'Water through the lens of climate change'

“Watermark” (acrylic on Yupo), by Greater Boston-based Patty Stone, in her show “Watermark’’, at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Sept. 1-26. Many of her paintings have been inspired by her close observation of the Charles River.

The gallery says:

“Patty Stone investigates the movement of water through the lens of climate change in a new series of abstract paintings and works on paper. Watermark juxtaposes a fluid paint surface against geometric shapes and lines of measurement suggesting rising tides or changing shorelines.’’

The Charles River at the Medfield-Millis (Mass.) town line

‘Beloved recognition’

Photo by Griffinstorm

Struck, was I, nor yet by Lightning –

Lightning – lets away

Power to perceive His Process

With Vitality –

Maimed – was I – yet not by Venture –

Stone of Stolid Boy –

Nor a Sportsman’s Peradventure –

Who mine Enemy?

Robbed – was I – intact to Bandit –

All my Mansion torn –

Sun – withdrawn to Recognition –

Furthest shining – done –

Yet was not the foe – of any –

Not the smallest Bird

In the nearest Orchard dwelling –

Be of Me – afraid –

Most – I love the Cause that slew Me –

Often as I die

It’s beloved Recognition

Holds a Sun on Me –

Best – at Setting – as is Nature’s –

Neither witnessed Rise

Till the infinite Aurora

In the Other’s Eyes –

— By Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)