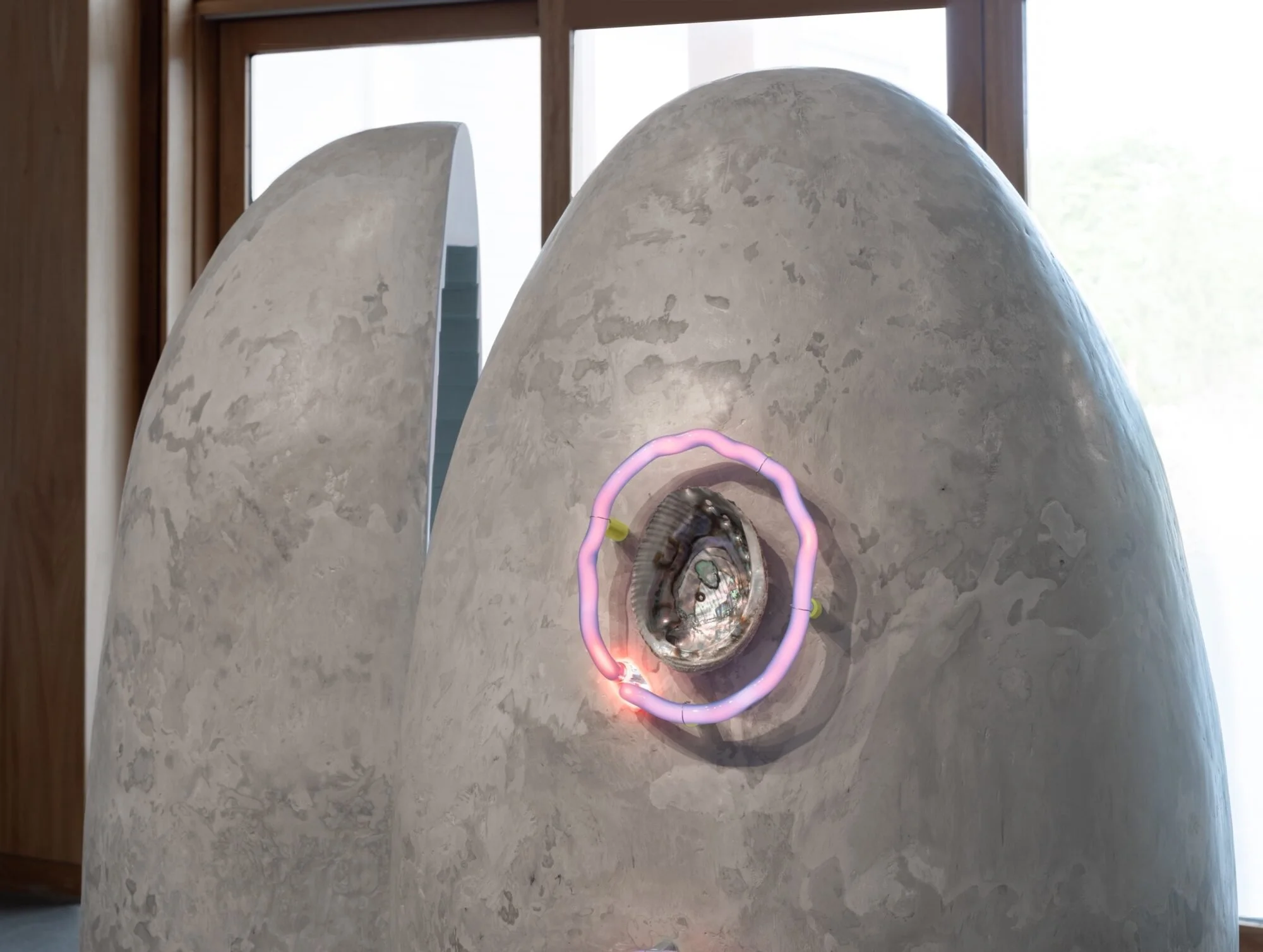

It’s watching you

Detail From Esther Ruiz’s show “Uncharted’,’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Greenwich, Conn., through Sept. 2.

The museum says:

“Uncharted’’ is Esther Ruiz’s first solo museum presentation on the East Coast, and the eighth installment of “Aldrich Projects,’’ a quarterly series featuring one work or a focused body of work by a single artist on the Museum’s campus. Debuting new sculptures from Ruiz’s “Beacon’’ series alongside “Codex” (2023), these enigmatic objects consider the relationships between the natural and the artificial, the familiar and the alien, and the temporal and transcendental.’’

Offshore wind turbines connected by underwater grid could revolutionize East Coast electricity sector

HANOVER, N.H.

Offshore winds have the potential to supply coastlines with massive, consistent flows of clean electricity. One study estimates wind farms just offshore could meet 11 times the projected global electricity demand in 2040.

In the U.S., the East Coast is an ideal location to capture this power, but there’s a problem: getting electricity from ocean wind farms to the cities and towns that need it.

While everyone wants reliable electricity in their homes and businesses, few support the construction of the transmission lines necessary to get it there. This has always been a problem, both in the U.S. and internationally, but it is becoming an even bigger challenge as countries speed toward net-zero carbon energy systems that will use more electricity.

The U.S. Department of Energy and 10 states in the Northeast States Collaborative on Interregional Transmission are working on a potentially transformative solution: plans for an offshore electric power grid.

How an offshore transmission backbone could reduce the number of transmission lines and land crossings. Illustrations by Billy Roberts, NREL

At the core of this grid would be backbone transmission lines off the East Coast, from North Carolina to Maine, where dozens of offshore wind projects are already in the pipeline.

The plans envision it supporting at least 85 gigawatts of offshore wind power by 2050 – close to the U.S. goal of 110 GW of installed wind power by mid-century, enough to power 40 million homes and up from 0.2 GW today. The Department of Energy and the Northeast States Collaborative formalized their goals in July 2024 through a multistate memorandum of understanding.

Emerging research from the Department of Energy, the research company Brattle and other groups suggests that an offshore electric power grid could mitigate key challenges to building new transmission lines on land and reduce the costs of offshore wind power.

Cutting costs would be welcome news – offshore wind project costs rose as much as 50% from 2021 to 2023. While some of the underlying causes have subsided, such as inflation and global supply chain disruptions, interest rates remain high, and the industry is still trying to find its footing in the U.S.

What is an offshore electric power grid?

Today’s offshore wind projects use a point-to-point, or radial design, where each offshore wind farm is individually connected to the onshore grid.

This method works if a region has only a few projects, but it quickly becomes more expensive due to the cabling and other infrastructure. Its lines are also disruptive to communities and marine life. And it requires more costly onshore grid upgrades.

Coordinated offshore transmission can avoid many of those costs with what the Department of Energy calls “meshed” or “backbone” designs.

Rather than individual connections to land, many offshore wind farms would be connected to a shared transmission line, which would connect to the onshore grid through strategically placed “points of interconnection.” This way, electricity produced by an offshore wind farm would be transmitted to where it is most needed, up and down the East Coast.

Several areas along the Atlantic continental shelf have been leased for wind power development. U.S. Department of the Interior, 2024

Even better, electricity generated onshore could also be transmitted through these shared lines to move energy to where it is needed. This could improve the resilience of power grids and reduce the need for new transmission lines over land, which have been notoriously difficult to gain approval for, especially on the East Coast.

Coordinated offshore transmission was part of early U.S. discussions on offshore wind planning and development. In the late 2000s when Google and partners first proposed the Atlantic Wind Connection, an offshore transmission project, the benefits in both offshore renewables and the entire energy system were intriguing. At the time, the U.S. had just one utility-scale offshore wind project in the pipeline, and it ultimately failed.

Today, the U.S. has 53 GW of offshore wind projects being planned or developed. As energy researchers, we believe coordinated offshore transmission is important for the industry to succeed at scale.

Offshore grid could save money, reduce impacts

By enabling power from offshore wind farms and onshore electricity generators to travel to more places, coordinated transmission can enhance grid reliability and enable electricity to get to where it is most needed. This reduces the need for more expensive and often more polluting power plants.

A 2024 report from the National Renewable Energy Lab found the benefits of a coordinated design are nearly three times higher than the costs when compared with a standard point-to-point design.

Studies from Europe, the U.K. and Brattle have pointed to additional benefits, including reducing planet-warming carbon emissions, cutting the number of beach crossings by a third and reducing the miles of transmission cables needed by 35% to 60%.

Three transmission designs show the difference between intraregional systems with several land connections and interregional and backbone designs. These three were investigated by the National Renewable Energy Lab in the Atlantic Offshore Wind Transmission Study. Illustrations by Billy Roberts, NREL

In the U.S., offshore transmission lines would be almost entirely in federal waters, potentially avoiding many of the conflicts associated with onshore projects, though it would still face challenges.

Challenges and next steps

Building an offshore grid will require some important changes.

First is changing government incentives. The federal investment tax credit for offshore wind, which covers at least 30% of the upfront capital cost of a project, does not currently help pay for coordinated transmission designs.

Second, planning needs to take everyone’s concerns into account from the beginning. While the overall benefits of coordinated transmission designs outweigh overall costs, who receives the benefits and who bears the costs matters. For example, more expensive power generators could earn less, and some communities feel threatened by offshore development.

Third, greater coordination will be needed among everyone involved to dispatch power to and from the regional grids. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s recent Order 1920, requiring power providers to plan for future needs, may serve as a blueprint, but it does not apply to interregional projects, such as an offshore transmission backbone connecting over a dozen states across three regions.

Several New England states are seeing economic growth from the offshore wind industry. Here, blades are prepared for shipping at a pier in New London, Conn. Elizabeth J. Wilson, CC BY-ND

The U.S. reached an important milestone in March 2024 with the completion of South Fork Wind, the country’s first utility-scale wind farm, bringing U.S. offshore wind power capacity to nearly 200 megawatts. Eight more projects are under construction or approved for construction. Once built, they would bring installed capacity to over 13 gigawatts, roughly the same as three dozen coal-fired power plants.

An offshore transmission backbone could support offshore wind development and the East Coast’s energy needs for generations to come.

The authors of this article:

Research Associate in Environmental Studies, Dartmouth College

Research Scholar, Ralph O’Connor Sustainable Energy Institute, Johns Hopkins University

Professor of Environmental Studies, Dartmouth College

Professor of Industrial Engineering Applied to Energy Policy, UMass Amherst

Disclosure statement

Abraham Silverman receives funding from Clean Grid Initiative. Abe previously worked at the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities on offshore wind and transmission matters. Abe also facilitates the Northeast States Collaborative on Interregional Transmission, which includes discussion of offshore wind and transmission matters.

Elizabeth J. Wilson receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the Sloan Foundation.

Erin Baker receives funding from the National Science Foundation, U.S. EPA, and U.S. Department of Energy

Tyler Hansen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

‘Between expectation and desire’

“She’s a luscious morsel,’’ by Saxtons River, Vt.-based artist Whitney Barrett at Canal Street Gallery, Bellows Falls, Vt.

He says:

“Using pattern, mark making and collage, I have been integrating found text and hybrid/abstracted human figures in static poses. These pieces explore questions of identity, story, and how we present to the outside world. I am interested in the way stories are told and implied, assumptions and miscommunication, as well as the tension between expectation and desire.’’

Amy Maxmen: Battling bird flu in the heat as U.S. struggles to contain outbreak

— Photo by Snowmanradio

“If a farm worker gets severely ill or dies from an H5N1 infection, it will be a stain on U.S. public health that we didn’t do more with the tools we have.’’

— Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University

Six people who work at a poultry farm in northeastern Colorado have tested positive for the bird flu, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported July 19. This brings the known number of U.S. cases this year to 10.

The workers were likely infected by chickens, which they had been tasked with killing in response to a bird flu outbreak at the farm. The endeavor occurred amid a heat wave, as outside temperatures soared to 104 degrees Fahrenheit.

“The barns in which culling occurs were no doubt even hotter,” said CDC principal deputy director Nirav Shah at a July 16 press briefing. Wearing N95 respirators, goggles, and other protective gear was a challenge. Industrial fans whipped feathers around the facility that could have carried the virus, Shah added.

In this environment, the farmworkers collected hundreds of chickens by hand and placed them into carts where they could be killed by carbon dioxide gas within two minutes.

“If a farm worker gets severely ill or dies from an H5N1 infection, it will be a stain on U.S. public health that we didn’t do more with the tools we have,” Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, posted on X. “You don’t send farm workers in to cull H5N1 infected birds without goggles and masks. Period. If it’s too hot to wear those protections, it’s too hot to cull. We need vaccines to be made available to farm workers. We have to stop gambling with peoples’ lives.”

More than 99 million chickens and turkeys have been infected with a highly pathogenic strain of the bird flu that emerged at U.S. poultry farms in early 2022. Since then, the federal government has compensated poultry farmers more than $1 billion for destroying infected flocks and eggs to keep outbreaks from spreading.

As summer temperatures rise across the country, Shah said, the agency is contending with how to offer farmworkers “safety from the virus, as well as safety from extreme heat.”

The H5N1 bird flu virus has spread among poultry farms around the world for nearly 30 years. An estimated 900 people have been infected by birds, and roughly half have died from the disease.

The virus made an unprecedented shift this year to dairy cattle in the U.S. This poses a higher threat because it means the virus has adapted to replicate within cows’ cells, which are more like human cells. The four other people diagnosed with bird flu this year in the U.S. worked on dairy farms with outbreaks.

Scientists have warned that the virus could mutate to spread from person to person, like the seasonal flu, and spark a pandemic. There’s no sign of that, yet.

So far, all 10 cases reported this year have been mild, consisting of eye irritation, a runny nose, and other respiratory symptoms. However, numbers remain too low to say anything certain about the disease because, in general, flu symptoms can vary among people with only a minority needing hospitalization.

The number of people who have gotten the virus from poultry or cattle may be higher than 10. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has tested only about 60 people over the past four months, and powerful diagnostic laboratories that typically detect diseases remain barred from testing for bird flu. Testing of farmworkers and animals is needed to detect the H5N1 bird flu virus, study it, and stop it before it becomes a fixture on farms.

Researchers have urged a more aggressive response from the CDC and other federal agencies to prevent future infections. Many people exposed regularly to livestock and poultry on farms still lack protective gear and education about the disease. And they don’t yet have permission to get a bird flu vaccine.

Nearly a dozen virology and outbreak experts recently interviewed by KFF Health News disagree with the CDC’s decision against vaccination, which may help prevent bird flu infection and hospitalization.

“We should be doing everything we can to eliminate the chances of dairy and poultry workers contracting this virus,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. “If this virus is given enough opportunities to jump from cows or poultry into people, it will eventually get better at infecting them.”

To understand whether cases are going undetected, researchers in Michigan have sent the CDC blood samples from workers on dairy farms. If they detect bird flu antibodies, it’s likely that people are more easily infected by cattle than previously believed.

“It’s possible that folks may have had symptoms that they didn’t feel comfortable reporting, or that their symptoms were so mild that they didn’t think they were worth mentioning,” said Natasha Bagdasarian, chief medical executive for the state of Michigan.

In hopes of thwarting a potential pandemic, the United States, United Kingdom, Netherlands, and about a dozen other countries are stockpiling millions of doses of a bird flu vaccine made by the vaccine company CSL Seqirus.

Seqirus’ most recent formulation was greenlighted last year by the European equivalent of the FDA, and an earlier version has the FDA’s approval. In June, Finland decided to offer vaccines to people who work on fur farms as a precaution because its mink and fox farms were hit by bird flu last year.

The CDC has controversially decided not to offer at-risk groups bird flu vaccines. Demetre Daskalakis, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told KFF Health News that the agency is not recommending a vaccine campaign at this point for several reasons, even though millions of doses are available. One is that cases still appear to be limited, and the virus isn’t spreading rapidly between people as they sneeze and breathe.

The agency continues to rate the public’s risk as low. In a statement posted in response to the new Colorado cases, the CDC said its bird flu recommendations remain the same: “An assessment of these cases will help inform whether this situation warrants a change to the human health risk assessment.”

Amy Maxmen is a journalist for Kaiser Family Foundation Health News.

‘Microcosm’

Archival photo of Tenants Harbor Light

“I thought to live on an island was like living on a boat. Islands intrigue me. You can see the perimeters of your world. It’s a microcosm.’’

— Jamie Wyeth (born 1946), American painter many of whose works are based on what he has seen on the Maine Coast, notably at Tenants Harbor and Monhegan Island. His base of operations is Tenants Harbor Light.

Monhegan Island in 1909

Bridge bathos and beauty

Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge, in foreground, and Bourne Bridge in December 1935 after soon after they were completed. The Sagamore Bridge is out of sight here.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Most readers have driven on the two vehicle bridges – the Sagamore and Bourne -- over the spectacular Cape Cod Canal and noticed that the Feds built them both in only two years – 1933-1935 – with equipment and building materials inferior to what we have now. The current bridges have been impressively sturdy, though driving on the two-way spans, with their too-narrow lanes, can be unnerving. Clench your teeth and look straight ahead!

There’s also the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge, also built in 1933-1935, allowing a bit of freight and seasonal passenger service on the Cape.

So the decision has been made to replace the bridges, via a combination of federal and state money. Officials say that construction of the new Sagamore Bridge won’t start until 2027 and building of a new Bourne Bridge until 2029. The hope is to complete the Sagamore Bridge by 2034 and the Bourne Bridge maybe by 2036. The total cost is projected to be $4.5 billion.

(Who of us old folks will be around to see the new bridges, and would we be too decrepit to drive on them? Would the new bridges make things, worse, not better, traffic-wise, by drawing even more people to the Cape?)

It’s very difficult to do big projects in America because of too many sometimes conflicting jurisdictions, too many permitting layers and the sometimes paralyzing fear of litigation. It would be nice if officials used the new bridges as a nation-leading example of how to speed up big projects.

I also thought of how more railroad service to the Cape would help cut down on what is often from May to October’s horrific car traffic going to and from what is a man-made island.

Likewise, Aquidneck Island would be more habitable if a railroad(s) – MBTA and/or Amtrak -- connected it with the outside world and took a lot of vehicles off the road. New bridges would, of course, be needed. The terminus would be at Thames Street in Newport, whence tourists could easily walk to many of the City by the Sea’s famous sights and sites. Alas, that’s more billions of bucks!

‘It would be energizing and uplifting if the new bridges we do put up in such watery places as Rhode Island and Massachusetts were more than just for vehicles. They could be lively attractions, providing dramatic views for pedestrians and bicyclists. There could be plantings on them and maybe even snack bars. They could become like public squares, albeit with anti-suicide fences….

A CapeFLYER train, providing seasonal service, crosses the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge on the Cape Main Line in 2013.

— Photo by Pi.1415926535

‘Ebb and flow’

— Photo by Snowmanradio

“What I remember is the ebb and flow of sound

That summer morning as the mower came and went

And came again, crescendo and diminuendo….’’

— From “The Sound I listened For,’’ by Robert Francis (1901-1987), Amherst, Mass.-based poet

A place to pay tribute to your (usually)most-loyal friends

Inside the Dog Chapel, at the Stephen Huneck Gallery, on Dog Mountain, in St. Johnsbury, Vt.

Outside of the Dog Chapel

— Photo by User:Dismas

Andrew Warburton: Where pixilated' came from

English pixies playing on the skeleton of a cow.

— John D. Batten. c.1894

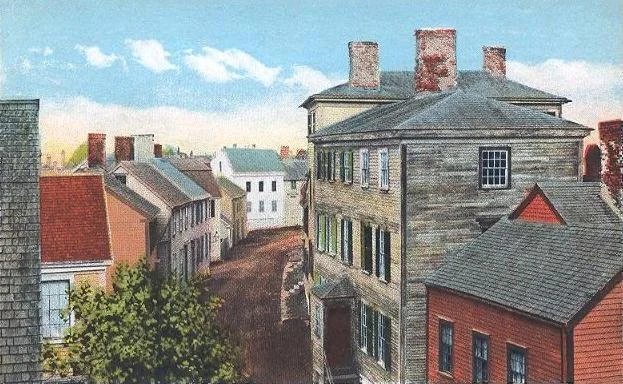

Front Street in Marblehead around the turn of the 20th Century.

1916 photo

Text excerpted from The New England Historical Society Web site

“When I say that the town of Marblehead on Massachusetts’s North Shore is unlike other coastal Massachusetts towns, I’m not simply referring to the fact that it’s teeming with fairies and pixies (which it is). Isolated from the state’s highway system on a remote peninsula, the town has always boasted a most unorthodox history.

“Think of it as the black sheep of Colonial New England. Whereas Puritans founded the surrounding settlements of Salem, Peabody, and Danvers to be pure and godly communities, Marblehead’s beginnings were more down to earth. According to historians Priscilla Sawyer Lord and Virginia Clegg Gamage, ‘irreligious settlers’ and ‘adventurous fishermen’ founded the town to escape the harsh dictates of Puritanism while making a living catching fish. In about 1629, these humble but industrious early settlers headed south east to a peninsula where the Naumkeag Tribe lived. They coexisted peacefully with the tribe while establishing the sleepy fishing village we know today.

“Over the next few hundred years, Marblehead saw an influx of fairy-acquainted immigrants from Scotland and the fishing regions of South West England: Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, and Somerset. According to the historian Samuel Roads, immigration from England’s South West accounted for what he called Marblehead’s ‘idiomatic peculiarities….’’’

Lilian Dove: Tagging seals with sensors helps scientists track changes in currents and climate

Weddell seal coming up for air in the Southern Ocean.

PROVIDENCE, R.I.

A surprising technique has helped scientists observe how Earth’s oceans are changing, and it’s not using specialized robots or artificial intelligence. It’s tagging seals.

Several species of seals, such Weddell seals, live around and on Antarctica and regularly dive more than 100 meters in search of their next meal. These seals are experts at swimming through the vigorous ocean currents that make up the Southern Ocean. Their tolerance for deep waters and ability to navigate rough currents make these adventurous creatures the perfect research assistants to help oceanographers like my colleagues and me study the Southern Ocean.

Seal sensors

Researchers have been attaching tags to the foreheads of seals for the past two decades to collect data in remote and inaccessible regions. A researcher tags the seal during mating season, when the marine mammal comes to shore to rest, and the tag remains attached to the seal for a year.

A researcher glues the tag to the seal’s head – tagging seals does not affect their behavior. The tag detaches after the seal molts and sheds its fur for a new coat each year.

The tag collects data while the seal dives and transmits its location and the scientific data back to researchers via satellite when the seal surfaces for air.

Scientists attach a tag to a seal after it is safely tranquilized. Etienne Pauthenet

First proposed in 2003, seal tagging has grown into an international collaboration with rigorous sensor accuracy standards and broad data sharing. Advances in satellite technology now allow scientists to have near-instant access to the data collected by a seal.

New scientific discoveries aided by seals

The tags attached to seals typically carry pressure, temperature and salinity sensors, all properties used to assess the ocean’s rising temperatures and changing currents. The sensors also often contain chlorophyll fluorometers, which can provide data about the water’s phytoplankton concentration.

Phytoplankton are tiny organisms that form the base of the oceanic food web. Their presence often means that animals such as fish and seals are around.

The seal sensors can also tell researchers about the effects of climate change around Antarctica. Approximately 150 billion tons of ice melts from Antarctica every year, contributing to global sea-level rise. This melting is driven by warm water carried to the ice shelves by oceanic currents.

With the data collected by seals, oceanographers have described some of the physical pathways this warm water travels to reach ice shelves and how currents transport the resulting melted ice away from glaciers.

Seals regularly dive under sea ice and near glacier ice shelves. These regions are challenging, and can even be dangerous, to sample with traditional oceanographic methods.

The amount of excess heat (shown as energy) that the upper ocean (above 700 meters), deep ocean (below 700 meters), atmosphere and Earth have been taking up has increased over the past few decades. All values are relative to 1971, and uncertainty in the ocean values dominates the total uncertainty (black dotted line). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Across the open Southern Ocean, away from the Antarctic coast, seal data has also shed light on another pathway causing ocean warming. Excess heat from the atmosphere moves from the ocean surface, which is in contact with the atmosphere, down to the interior ocean in highly localized regions. In these areas, heat moves into the deep ocean, where it can’t be dissipated out through the atmosphere.

The ocean stores most of the heat energy put into the atmosphere from human activity. So, understanding how this heat moves around helps researchers monitor oceans around the globe.

Seal behavior shaped by ocean physics

The seal data also provides marine biologists with information about the seals themselves. Scientists can determine where seals look for food. Some regions, called fronts, are hot spots for elephant seals to hunt for food.

In fronts, the ocean’s circulation creates turbulence and mixes water in a way that brings nutrients up to the ocean’s surface, where phytoplankton can use them. As a result, fronts can have phytoplankton blooms, which attract fish and seals.

While we traditionally consider the ocean to be blue, it can actually appear green from space because of phytoplankton blooms. Currents can stretch out these blooms, and seals prefer to feed in these locations.

Scientists use the tag data to see how seals are adapting to a changing climate and warming ocean. In the short term, seals may benefit from more ice melt around the Antarctic continent, as they tend to find more food in coastal areas with holes in the ice. Rising subsurface ocean temperatures, however, may change where their prey is and ultimately threaten seals’ ability to thrive.

Seals have helped scientists understand and observe some of the most remote regions on Earth. On a changing planet, seal tag data will continue to provide observations of their ocean environment, which has vital implications for the rest of Earth’s climate system.

Lilian Dove is a post-doctoral fellow of oceanography at Brown University.

Lilian Dove does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Blue falls

“Plumb 36 C (Leaves of Grass)’’ (UV polymer on aluminum), by Henry Mandell, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston.

Chris Powell: Block housing development and your property taxes may rise

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Blame for rising property taxes in Connecticut may be shared more broadly than most people think. It's not just the fault of elected officials who yield to the demands of special interests, particularly the demands of government- employee unions for higher wages and benefits.

Property taxes are determined in large part by property values, and the great inflation created by the spectacular overspending and over-borrowing by the Trump and Biden administrations and Congress have increased the nominal value of nearly everything, including residential property.

Then there is the flood of illegal immigration. The millions of illegal immigrants admitted in recent years must live somewhere, and the federal government and state government are often subsidizing their housing, causing scarcity. Without so many illegal immigrants and government subsidies for their housing, demand would be reduced, more properties would be vacant, and residential rents, prices and property values would fall.

There is still another cause of housing scarcity and rising property values and taxes: state and municipal policy that restricts supply, such as exclusive zoning and what is called farmland preservation, a politically correct mechanism for preventing housing development. People tend not to associate these policies with rising property taxes, which homeowners pay directly and tenants pay indirectly through their rent.

But maybe the association will be noticed after more periodic municipality-wide property revaluations, such as the ones that New London and Norwich recently underwent.

According to The Day of New London, residential-property values in the little city just rose by an average of 60 percent, and many people are shocked by the corresponding increase in their property taxes, since commercial- property values didn't rise that much if at all.

With employment booming at submarine manufacturer Electric Boat in neighboring Groton, New London and nearby towns especially need more housing. But since the housing shortage, rising property values, and rising property taxes are statewide and national phenomena, any town could facilitate a building boom and still not knock housing values down much.

At least people should take their rising property-tax bills as a reminder not to complain so much about new housing. Obstructing new housing means scarcity, and scarcity means that housing prices will be bid up, taking housing taxes with them.

LEAVE IDAHO ALONE: Abortion rights are more secure in Connecticut than they are in many other states.

Having long ago incorporated into its own law the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Roe v. Wade, Connecticut leaves abortion unrestricted prior to fetal viability, and even then few seem to be guarding against the abortion of viable fetuses. Connecticut also allows abortions for minors without parental consent, enabling child molesters to erase the evidence of their crimes.

Still, the abortion policies of other states have Connecticut Atty. Gen. William Tong in a frenzy. Lately Tong has been fulminating about Idaho's restrictive abortion law and has even had filed a brief in an Idaho case in federal court, though the case has no bearing on Connecticut.

Speaking of Idaho's law the other day, the attorney general said: "This threat and severe state abortion bans are not going away. We're going to have to keep fighting these fights in every court in every state where patients' lives and reproductive freedom are at risk."

But why? Reversing Roe two years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court didn't restrict abortion anywhere. It just returned abortion policy to the states, restoring some federalism.

Who is Connecticut's attorney general to seek to override democracy in Idaho? Presumably if enough of the women of Idaho wanted their state's abortion law to be like Connecticut's, they could mobilize to achieve it. Apparently many if, not most, women in Idaho want abortion tightly restricted.

No one has to live in Idaho or Connecticut.

And where does the attorney general find the authority to intervene in cases having no bearing on Connecticut? State law confines the attorney general's office to legal matters "in which the state is a party or is interested." Abortion law in Idaho is not a state interest in Connecticut, just a partisan political one.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Fragile places’

“Distant Lands” (cold wax, oil stick, graphite, ink, on Bristol board), by Natick, Mass.-based artist Deborah Marum Pressman, in the group show “Forces of Nature,’’ at the Ava Gallery, Lebanon, N.H., through Aug. 24.

She says:

‘‘My relationship with the land is with the fragile places . . . their beauty and vulnerability are undeniable.’’

Invasive plants move fast

Japanese knotweed is strangling native plants in southern New England.

— Photo by harum.koh

A barberry shoot

— Photo by MPF

Text excerpted from an ecoRI News article by Frank Carini

“An international team of scientists recently discovered that nonnative species are expanding their ranges up to 1,000 times faster than native ones, in large part due to human help…. {New England has seen a massive invasion of non-native plants, such as barberry, in recent decades.}

“Barberry was brought to the United States from Japan and eastern Asia in the late 1800s…. {T}he prickly shrub easily spreads into woodlands, pastures, and meadows, where, like many invasives imported from faraway lands, it strangles native species.

“{R}esearchers found that even seemingly sedentary nonnative plants are moving at three times the speed of their native counterparts in a race where, because of the rapid pace of climate change and its effect on habitat, speed matters.’’

Here’s the whole article.

Inquiring into immigration

“What a New Day’’ (oil on canvas) by Taiwanese-American artist Chris Chou, in the group show “Roots of Passage: Artists Examine Immigration,’’ at Atlantic Works Gallery, East Boston, through Aug. 17.

— Image courtesy of Atlantic Works Gallery.

The gallery says the show is an opportunity for artists to investigate immigration from various viewpoints

“With East Boston’s rich tradition of welcoming immigrants, and now with immigration such a burning issue in the news today, the gallery felt compelled to not only examine, but to celebrate the issue," according to Atlantic Works Gallery founding member Eric Hess.

East Boston Immigration Station circa 1922.

Llewellyn King: How the move to a MAGA-style Britain flopped

Areas of the world that were part of the British Empire, with current British Overseas Territories underlined in red.

— Photo by RedStorm1368

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Make America Great Again.” Those words have been gently haunting me not because of their political-loading, but because they have been reminding me of something, like the snatches of a tune or a poem which isn’t fully remembered, but which drifts into your consciousness from time to time.

Then it came to me: It wasn’t the words, but the meaning; or, more precisely, the reasoning behind the meaning.

I grew up among the last embers of the British Empire, in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). I am often asked what it was like there.

All I can tell you is that it was like growing up in Britain, maybe in one of the nicer places in the Home Counties (those adjacent to London), but with some very African aspects and, of course, with the Africans themselves, whose land it was until Cecil John Rhodes and his British South Africa Company decided that it should be British; part of a dream that Britain would rule from Cape Town to Cairo.

Evelyn Waugh, the British author, said of Southern Rhodesia in 1937 that the settlers had a “morbid lack of curiosity” about the indigenous people. Although it was less heinous than it sounds, there was a lot of truth to that. They were there and now we were there; and it was how it was with two very different peoples on the same piece of land.

But by the 1950s, change was in the air. Britain came out of World War II less interested in its empire than it had ever been. In 1947, under the Labor government of Clement Attlee, which came to power after the wartime government of Winston Churchill, it relinquished control of the Indian subcontinent — now comprising India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

It was set to gradually withdraw from the rest of the world. The empire was to be renamed the Commonwealth and was to be a club of former possessions, often more semantically connected than united in other ways.

But the end of the empire wasn’t universally accepted, and it wasn’t accepted in the African colonies that had attracted British settlers, always referred to not as “whites” but as “Europeans.”

I can remember the mutterings and a widespread belief that the greatness that had put “Great” into the name Great Britain would return. The world map would remain with Britain's incredible holdings in Asia and Africa, colored for all time in red. People said things like the “British lion will awake, just you see.”

It was a hope that there would be a return to what were regarded as the glory days of the empire when Britain led the world militarily, politically, culturally, scientifically, and with what was deeply believed to be British exceptionalism.

That feeling, while nearly universal among colonials, wasn’t shared by the citizens back home in Britain. They differed from those in the colonies in that they were sick of war and were delighted by the social services which the Labor government had introduced, like universal healthcare, and weren’t rescinded by the second Churchill administration, which took power in 1951.

The empire was on its last legs and the declaration by Churchill in 1942, “I did not become the king’s first minister to preside over the dissolution of the British Empire,” was long forgotten. But not in the colonies and certainly not where I was. Our fathers had served in the war and were super-patriotic.

While in Britain they were experimenting with socialism and the trade unions were amassing power, and migration from the West indies had begun changing attitudes, in the colonies, belief flourished in what might now be called a movement to make Britain great again.

In London in 1954, it got an organization, the League of Empire Loyalists, which was more warmly embraced in the dwindling empire than it was in Britain. It was founded by an extreme conservative, Arthur K. Chesterton, who had had fascist sympathies before the war.

In Britain, the league attracted some extreme right-wing Conservative members of parliament but little public support. Where I was, it was quite simply the organization that was going to Make Britain Great Again.

It fizzled after a Conservative prime minister, Harold MacMillan, put an end to dreaming of the past. He said in a speech in South Africa that “winds of change” were blowing through Africa, though most settlers still believed in the return of empire.

It took the war of independence in Rhodesia to bring home MacMillan’s message. We weren’t going to Make Britain Great Again.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he based in Rhode Island.

whchronicle.com

Coastal confrontation

From Boston-based artist Jessica Straus’s show “Stemming the Tide,’’ at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum, through Oct. 19

The museum says:

“A segmented map stretching across the gallery floor and rising to the ceiling is the central feature of Jessica Straus’s immersive installation. Its scale dwarfs us. The distinctive New England shoreline is recognizable. This is the Gulf of Maine, with waters descending from Ktqmkuk, now called Newfoundland, to Patuxet, the crook of land stretching out to the sea that we know as Cape Cod.

“Paired with the map is a series of photographs, partially occluded by hand-knotted fishing nets. In each image, a piece of the map floats atop lapping ocean waters, sometimes with the artist and other times adrift. The mesmerizing images allow us to contemplate the seen and unseen currents of the ocean.

“Deftly carved fish—cod—are scattered across the map. They are painted a ghostly white. In 1602, when Bartholomew Gosnold sailed into the southern terminus of the Gulf of Maine, its waters teemed with giant cod. That iconic fish is no longer abundant or giant.

“Woven together, the elements in “Stemming the Tide’’ provide a multifaceted and open-ended viewing experience.’’

Zachary Albert: How the Heritage Foundation pushes right-wing policies

As the 2024 presidential election heats up, some people are hearing about the Heritage Foundation for the first time. The conservative think tank has a new, ambitious and controversial policy plan, Project 2025, which calls for an overhaul of American public policy and government.

Project 2025 lays out many standard conservative ideas – like prioritizing energy production over environmental and climate-change concerns, and rejecting the idea of abortion as health care – along with some much more extreme ones, like criminalizing pornography. And it proposes to eliminate or restructure countless government agencies in line with conservative ideology.

While think tanks sometimes have the reputation of being stuffy academic institutions detached from day-to-day politics, Heritage is far different. By design, Heritage was founded to not only develop conservative policy ideas but also to advance them through direct political advocacy.

All think tanks are classified as 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organizations, which are prohibited from engaging in elections and can take part in only a small amount of political lobbying. But some, like Heritage, also form affiliated 501(c)(4) organizations that allow them to participate in campaigns and lobby extensively. Heritage is one of the sponsors of the Republican National Convention, which wrapped up in Milwaukee on July 18.

In research for my forthcoming book, Partisan Policy Networks, I’ve found that a growing share of think tanks are explicitly ideological, aligned with a single political party, and engaged in direct policy advocacy.

Still, Heritage stands out from all of the groups I investigated. It is much more conservative and more closely aligned with former President Donald Trump’s style of Republicanism. Heritage is also more aggressive in its advocacy for conservative ideas, pairing campaign spending with lobbying and large-scale grassroots mobilization.

Americans should expect to hear a lot more about its ideas, like those outlined in Project 2025, if Trump is reelected in November 2024.

Kevin Roberts, president of the Heritage Foundation, speaks with members of the conservative House Freedom Caucus during a Capitol Hill news conference in September 2023. Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via Getty Images

A new type of think tank

Two Republican congressional staffers, Ed Feulner and Paul Weyrich, formed Heritage in 1973 as an explicit rebuke to existing think tanks that they thought were either too liberal or too meek in advancing conservative ideas.

Feulner and Weyrich were particularly incensed about how a preeminent conservative think tank at the time, the American Enterprise Institute, or AEI, timed its release of a policy report in 1971 on whether to approve government funding for supersonic transport airplanes, which can fly faster than the speed of sound. AEI published its recommendations several days after Congress voted on the issue, because it “didn’t want to try to affect the outcome of the vote.”

Heritage turns this philosophy on its head. Rather than producing policy research for its own sake, Heritage conducts research, as one employee told me in 2018, “to build a case, to make the argument for policy change.”

For example, Heritage’s affiliated 501(c)(4) advocacy organization, Heritage Action for America, and Sentinel Action Fund, a Super PAC set up by Heritage Action in 2022, spend money to influence elections and lobby elected officials on issues as diverse as taxation, abortion, immigration and the environment.

For this reason, some scholars and politicos call Heritage and other similar groups “do tanks” rather than “think tanks.”

Because Sentinel Action Fund is a Super PAC, it can raise and spend unlimited amounts of money to influence elections so long as they do not coordinate with candidate campaigns. Sentinel Action Fund then spent more than US$13 million on voter outreach and advertising in the 2022 midterm elections. The fund’s self-described aim was to ensure GOP majorities in the House and Senate by aiding “key conservative fighters” in “tough general elections.” Sentinel Action Fund Vice President of Communications Carson Steelman said that in 2024, “the Sentinel Action Fund is totally legally separate from Heritage Action.”

Former Vice President Dick Cheney addresses the Heritage Foundation in April 2007 in Chicago. Jeff Haynes/AFP via Getty Images

People, not just money

But it’s the people, even more than money, that make Heritage influential, my research shows.

Heritage has directly worked to place former and current employees in congressional offices and the executive branch. More than 70 former and current Heritage staffers began working for the Trump administration by 2017 – and four current Heritage staffers were members of Trump’s cabinet in 2021.

Heritage also says that it has more than 2 million local, volunteer activists and roughly 20,000 “Sentinel activists” who receive information from Heritage and take part in organized campaigns to push for conservative policies. My interviews show that activists who partner with Heritage take part in strategy calls, contact elected representatives with coordinated messages and amplify the organization’s messaging on social media.

In one example from 2021, Heritage Foundation developed a report on election fraud and voter integrity. Heritage Action for America, meanwhile, coordinated volunteers to deliver this report to Georgia legislators, had staffers meet with these legislators to advise them on passing new voting restrictions, and paid for television advertising urging citizens to support such laws.

Heritage, Trump and Project 2025

All these efforts add up to a great deal of influence within the Republican Party. Heritage has played a key role in pushing Republicans toward more conservative policies since its creation.

When Ronald Reagan took office as president in 1981, for example, the Heritage Foundation had a ready-made conservative agenda for the new administration. By the end of his first term, Reagan executed more than 60% of the think tank’s policy recommendations.

When Trump took office in 2017, Heritage was again ready with friendly staffers and a handy policy agenda, called the Blueprint for Reorganization. By the end of Trump’s first year in office, Heritage boasted that he “had embraced 64 percent of our 321 recommendations,” among them key conservative priorities like tax reform, regulatory rollback and increased defense spending.

Project 2025 is similar to these other sets of recommendations for Republican politicians and presidential candidates. It outlines an agenda for a new president to adopt and a team of experts to help them.

But Project 2025 has taken on a different bent compared with earlier blueprints. Kevin Roberts, the president of Heritage, has described the group’s role as “institutionalizing Trumpism.”

This is probably why Project 2025, and Heritage, have received such an unusually large amount of attention in recent months. The fact that a wonky, 900-page policy memo has been the focus of countless news articles and hundreds of Biden campaign tweets, especially before the 2024 election, is a telling indication of its expected influence.

For its part, the Trump campaign has maintained distance from the project, as Trump himself has implausibly claimed that he knows nothing about it.

He is likely keeping his distance from Project 2025 because parts of the agenda are far too extreme for all but the most die-hard conservative activists. But even if Trump isn’t campaigning on these policies, Americans should expect Heritage ideas to matter greatly in a second Trump administration. The Heritage Foundation is built for this goal.

Zachary Albert is an assistant professor of politics at Brandeis University, in Waltham

Zachary Albert does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.

Art from a very bloody business

“Scrimshaw Utensils, Pie Crimpers and Jagging Wheels” (19th century) (whale bone), at the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

— Photo by Beth Neville

Japanese narrative screen showing a whale hunt off Wakayama.

Trying to create 'multimodal paradise' along Emerald Necklace

What part it would look like

Excerpted from The Boston Guardian

(New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian)

State planners have finalized plans to revitalize Boston’s Bowker Overpass, the Fenway’s eastern gate, repairing crumbling road infrastructure and turning a dangerous pedestrian intersection into a multimodal paradise.

The Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) gave the public its most complete picture yet on July 11. The public forum saw general support from residents and civic groups eager to see the broader Charlesgate project move toward fully opening that part of the Emerald Necklace.

Today, the 60-year old Bowker overpass is a knot of asphalt roads, connecting Boylston Street to Commonwealth Avenue over the I-90. Officials showed pictures of crumbling concrete and exposed rebar rusting away in the elements…..

The new layout will offer distinct paths for bikes, cars and pedestrians all the way to Commonwealth Avenue from either direction, with bikes and pedestrians sharing some parts.

The offramps will also be redesigned, with one new road to Charlesgate west replacing the ramps on either side to Commonwealth Avenue.