Faith and sex in New England

The Congregational Church of Middlebury, Vt.

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

— Photo by Ms Sarah Welch

“In New England, especially, [faith] is like sex. It's very personal. You don't bring it out and talk about it. “

— Carl Frederick Buechner (born 1926), American writer and Presbyterian minister. He lives in Vermont. He describes his area:

“Our house is on the eastern slope of Rupert Mountain, just off a country road, still unpaved then, and five miles from the nearest town ... Even at the most unpromising times of year – in mudtime, on bleak, snowless winter days – it is in so many unexpected ways beautiful that even after all this time I have never quite gotten used to it. I have seen other places equally beautiful in my time, but never, anywhere, have I seen one more so.’’

In Rupert, Vt.

Ocean warming to continue to move lobster, scallop habitats

Lobsters awaiting purchase in Trenton, Maine.

— Photo by Billy Hathorn

An Atlantic Bay Scallop.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Researchers have projected significant changes in the habitat of commercially important American lobster and sea scallops along the Northeast continental shelf. They used a suite of models to estimate how species will react as waters warm. The researchers suggest that American lobster will move further offshore and sea scallops will shift to the north in the coming decades. {Editor’s note: New Bedford is by far the largest port for the sea-scallop fishery.}

The study’s findings were published recently in Diversity and Distributions. They pose fishery-management challenges as the changes can move stocks into and out of fixed management areas. Habitats within current management areas will also experience changes — some will show species increases, others decreases and others will experience no change.

“Changes in stock distribution affect where fish and shellfish can be caught and who has access to them over time,” said Vincent Saba, a fishery biologist in the Ecosystems Dynamics and Assessment Branch at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center and a co-author of the study. “American lobster and sea scallops are two of the most economically valuable single-species fisheries in the entire United States. They are also important to the economic and cultural well-being of coastal communities in the Northeast. Any changes to their distribution and abundance will have major impacts.”

Saba and colleagues used a group of species distribution models and a high-resolution global climate model. They projected the possible impact of climate change on suitable habitat for the two species in the large Northeast continental shelf marine ecosystem. This ecosystem includes waters of the Gulf of Maine, Georges Bank, the Mid-Atlantic Bight and off southern New England.

The high-resolution global-climate model generated projections of future ocean-bottom temperatures and salinity conditions across the ecosystem, and identified where suitable habitat would occur for the two species.

To reduce bias and uncertainty in the model projections, the team used nearshore and offshore fisheries independent trawl survey data to train the habitat models. Those data were collected on multiple surveys over a wide geographic area from 1984 to 2016. The model combined this information with historical temperature and salinity data. It also incorporated 80 years of projected bottom temperature and salinity changes in response to a high greenhouse-gas emissions scenario. That scenario has an annual 1 percent increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

American lobsters are large, mobile animals that migrate to find optimal biological and physical conditions. Sea scallops are bivalve mollusks that are largely sedentary, especially during their adult phase. Both species are affected by changes in water temperature, salinity, ocean currents and other oceanographic conditions.

Projected warming for the next 80 years showed deep areas in the Gulf of Maine becoming increasingly suitable lobster habitat. During the spring, western Long Island Sound and the area south of Rhode Island in the southern New England region showed habitat suitability. That suitability decreased in the fall. Warmer water in these southern areas has led to a significant decline in the lobster fishery in recent decades, according to NOAA Fisheries.

Sea-scallop distribution showed a clear northerly trend, with declining habitat suitability in the Mid-Atlantic Bight, southern New England and Georges Bank areas.

“This study suggests that ocean warming due to climate change will act as a likely stressor to the ecosystem’s southern lobster and sea-scallop fisheries and continues to drive further contraction of sea scallop and lobster habitats into the northern areas,” Saba said. “Our study only looked at ocean temperature and salinity, but other factors such as ocean acidification and changes in predation can also impact these species.”

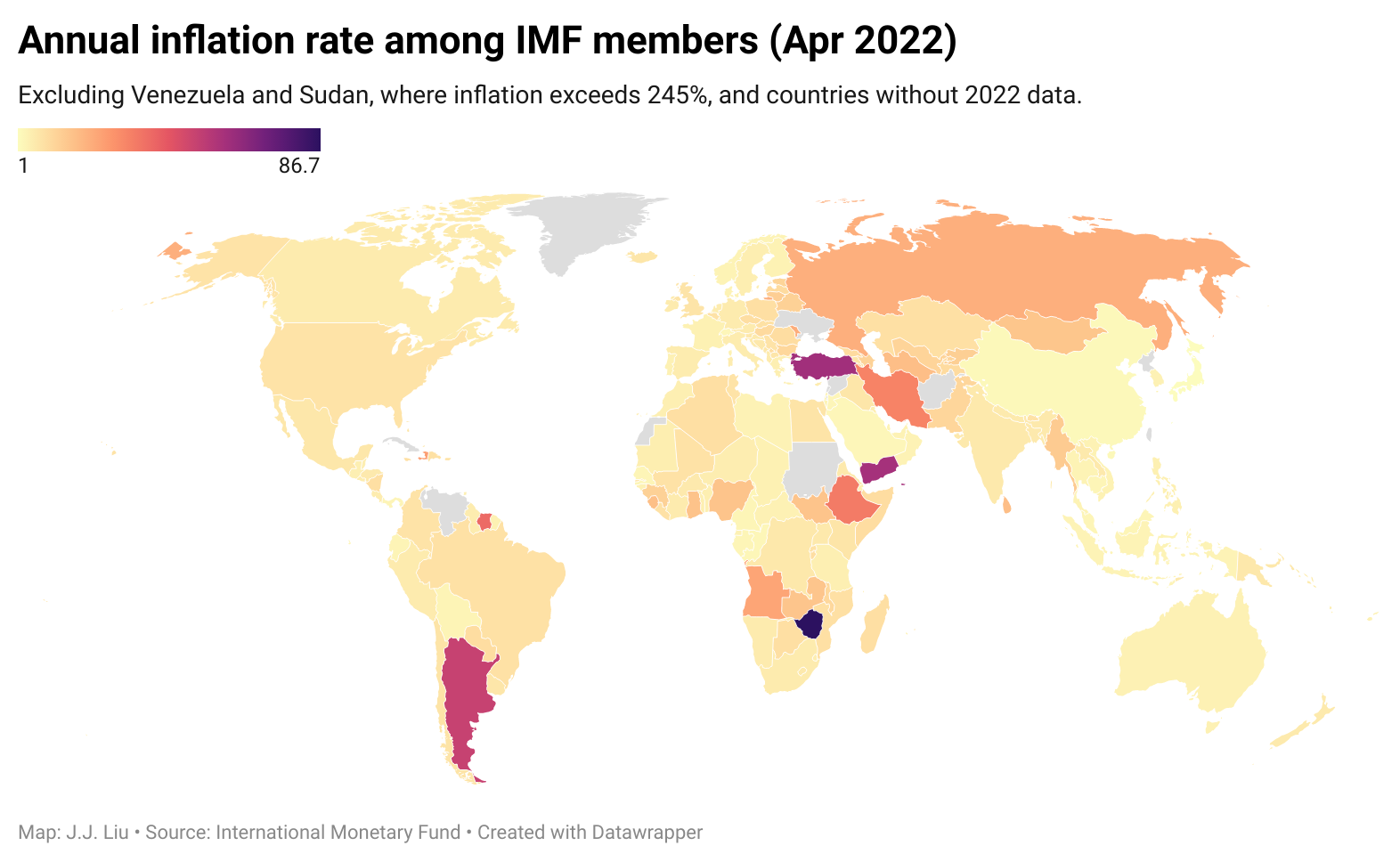

Chris Powell: Conn. budget surplus the flip side of inflation

Price adjustment

— Photo by Jim.henderson

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut state government has had worse managers than Gov. Ned Lamont, but nobody should be much impressed by the huge financial surplus over which he is presiding -- more than $4 billion, equivalent to a fifth of state government's annual budget.

For the surplus is not a product of any astounding new efficiencies in state government achieved by the Lamont administration.

No, state government still spends more every year without any marked improvement in service to the public or the state's living standards.

Instead the surplus arises from billions of dollars in emergency cash from the federal government, distributed in the name of relief from the recent virus epidemic, and from big increases in state capital gains tax revenue.

Most state governments are enjoying big surpluses for the same reasons. But happy days are not really here again, for an old saying from Wall Street counsels caution: Don't mistake a bull market for genius.

Caution is especially advisable now because, on top of the termination of that emergency federal aid, the stock market has more often than not been falling for a few months and is no longer producing capital gains for people who, to get richer, had to do little more than hang around.

The capital gains on which they lately have been paying much more in state taxes are, along with all that federal money propping up the state's financial reserves, mainly the other side of the inflation that is devastating living standards throughout the country and the world.

The U.S. money supply, determined entirely by the federal government, is estimated to have increased by about 35 percent in the last three years even as the number of full-time workers fell, government paid people for not working, and production declined.

More money amid less production is the recipe for inflation, and perhaps not so coincidentally Connecticut state government's financial surplus of about 20 percent of the annual budget is closer to the real annual rate of inflation than the official rate misleadingly calculated by the government, which lately has been about 9 percent.

State government's financial position may look great but it has come at a great cost. Government has saved itself but not the people.

xxx

Connecticut's buzz word of the moment seems to be "equity." It sanitizes almost anything, including the state-licensed growing and retailing of marijuana. Under Connecticut's new marijuana-legalization program, licenses are to be required for large-scale growing of marijuana and to be limited to companies involving people from areas that saw a high level of prosecutions in the "war on drugs."

People who obeyed the drug laws will get no such privileges for their good citizenship.

In essence marijuana licenses are becoming political patronage. Meeting clear criteria won't be enough. The state Consumer Protection Department will award licenses not just according to the criteria but also as favoritism.

So it's not surprising that, as the Connecticut Examiner reported last week, a grower's license is likely to be awarded to a company owned in part by former state Sen. Art Linares, a Republican married to Stamford Mayor Caroline Simmons, a Democrat and former state representative.

That's called working both sides of the street.

According to the Examiner, the "equity" part of Linares's application is a partner who "has lived for five of the last 10 years in a disproportionately impacted area of Connecticut."

That is, a front man. How just and remedial!

All this evokes how Connecticut handled the start of cable television 50 years ago. State law divided the state into franchise areas with a single license to be issued for each. To qualify, a company had to be owned by local residents. But they weren't required to have the capital and expertise needed to operate the business.

So local politically connected people started such companies, got the franchise license, and sold the franchise to a real cable TV company, making a bundle. This racket came to be called "rent a citizen."

Today's marijuana-licensing racket will enrich people who need only to be friends with someone who can pretend to have been oppressed.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

And have an exciting night

“Push Your Beds Together’’ (acrylic, oil stick, pastel, spray paint and latex on canvas), by Brazilian artist Thai Mainhard, in her show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through Aug. 28.

The gallery says:

“Thai Mainhard’s abstract paintings combine expressive mark making with dense blocks of color to create complex and emotive compositions that navigate the space between chaos and calm. Her works draw inspiration from Abstract Expressionism, recalling the work of Willem de Kooning, Cy Twombly and Joan Mitchell. Mainhard works with a variety of media—including oil paint, oil sticks, spray paint, and charcoal—to create intuitive imagery that externalizes her feelings and personal experiences.’’

‘Small frightened faces’

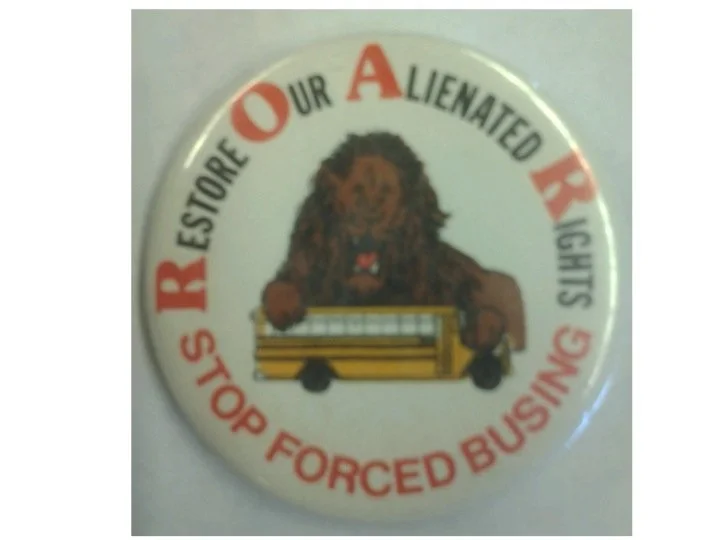

Button of organization of white Boston residents (particularly from South Boston and Dorchester) opposed to court orders that mandated the busing of students to help desegregate the city’s public schools. Its initials, of course, were R.O.A.R.

“In 1974, when the City of Boston was desegregating its schools, I watched the news with my dad and saw the police escorts in riot gear, the protesters screaming at the buses, small frightened faces in their windows.’’

Wendell Pierce (born 1963), American actor and businessman. He’s a Black man.

Goes with the territory

“The roaring alongside he takes for granted,

and that every so often the world is bound to shake.

“He runs, he runs to the south, finical, awkward,

in a state of controlled panic, a student of Blake.’’

—From “Sandpiper,’’ by famed American poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), who was born in Worcester and died in Boston. She lived in Brazil, among other places.

She spent parts of six summers (1974-1979) on the island town of North Haven Island, Maine, best known for its summer colony of prominent Northeasterners, particularly Boston Brahmins. Among the more notable summer residents was the painter Frank Weston Benson, who rented the Wooster Farm as a summer home and painted several canvases set on the island.

Harborfront and ferry terminal on the island of North Haven.

— Photo by Jp498

“Summer,’’ by Frank Weston Benson

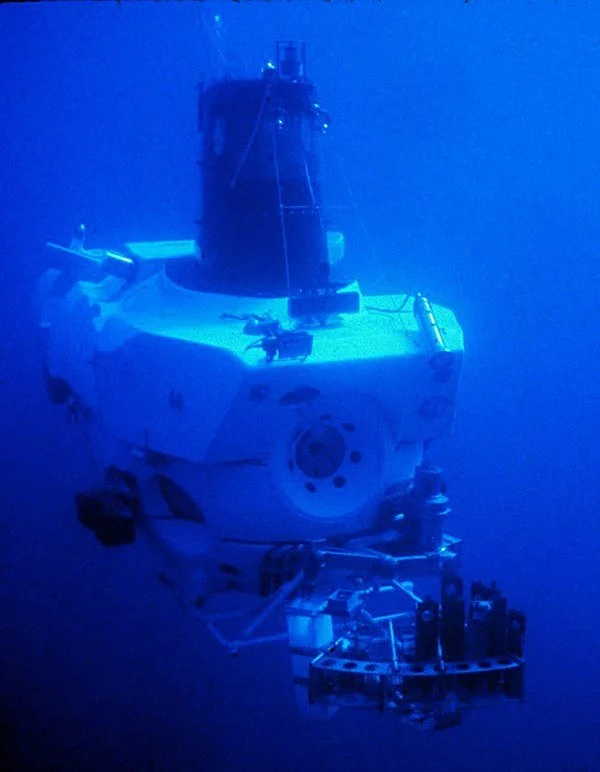

Enjoying the heat, for a while

— Photo by Judson McCranie

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I love air conditioning, as I suspect most people do. We may be bankrupted by having so many cooling devices in our old house, but, hey, one is an environmentally friendly -- relatively! -- a heat pump. Of course, with most of our electricity still generated by fossil fuel, we help heat up the world with our air conditioners.

Still, from time to time, I look back fondly to those dog days of 60 years ago when we sat in a screened-in back porch with a cool slate floor reading and talking in a desultory way in the humid heat with the soft drone of the insects and the whisper of the southwest wind in the oak trees in the background. And how pleasant it was to bring our first (and surprisingly heavy) portable TV out to the porch so we could watch the likes of baseball, Perry Mason and political party conventions in the semi-outdoors, often with Popsicles slicking our hands, though my parents’ steady smoking reduced these pleasures a tad.

It was lovely, to a point, being languid. We lose something in being more and more cut off from the feel of the seasons. Now I’ll go back inside again from the front porch. Hot out here

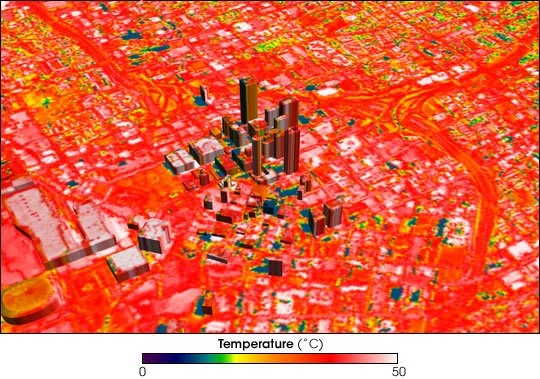

Illustration of urban heat exposure via a temperature-distribution map: Blue shows (relativel) cool temperatures, red warm, and white hot areas.

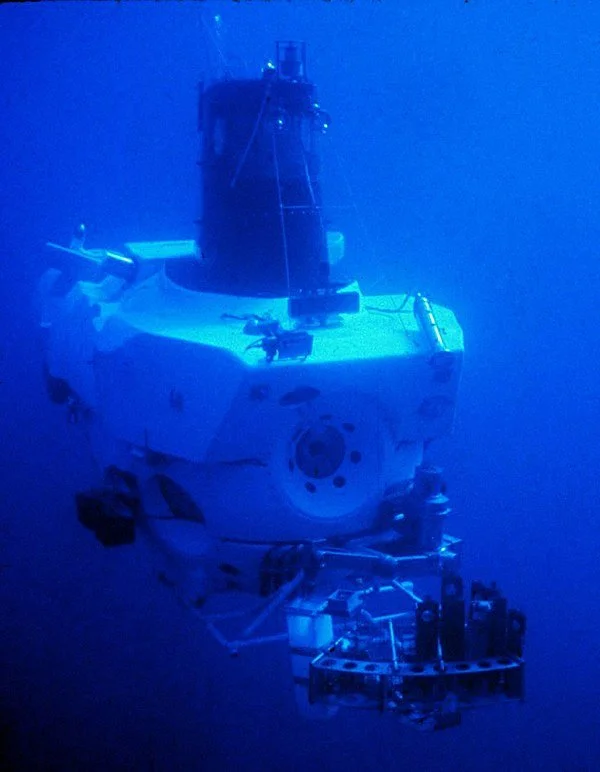

‘Alvin’ goes the deepest yet

Alvin at work

An edited version of a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report:

“The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s (a New England Council member) human-guided submersible ‘Alvin’ research vessel has made history by reaching a depth of 6,453 meters (about 21,117 feet). The three-person crew guided the submersible in the Puerto Rico Trench, off that island .… Alvin’s success has led to 99 percent of the seafloor being available for the submersible to explore.

“The submersible is well-known around the world for being an icon of excellent scientific data collecting and engineering. ‘Alvin’ is one of the only U.S. submersibles that have the equipment to carry humans and gather scientific data from extreme depths. Since its initial launch, ‘Alvin’ has carried out 5,086 successful dives. Its long history goes back to when Woods Hole scientist Robert Ballard used ‘Alvin’ to explore the wreckage of the HM Titanic. This summer ‘Alvin’ went through an intense series of sea trials overseen by the NAVSEA, an organization responsible for building U.S. Navy ships. The trials permitted ‘Alvin’ to dive to its maximum depth. The next step for ‘Alvin’ will be a two-week National Science Foundation-funded verification expedition to determine if ‘Alvin’ can maintain its ability to support deep-sea scientific research.

“Woods Hole President Peter de Menocal said, “[i]nvestments in unique tools like ‘Alvin’ accelerate scientific discovery at the frontier of knowledge. Alvin’s new ability to dive deeper than ever before will help us learn even more about the planet and bring us a greater appreciation for what the ocean does for all of us every day.”’

Read more from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Woods Hole (part of Falmouth), with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Marine Biological Laboratory buildings

Coral crisis; failed colony

“Bleached” {by ocean acidification?} (oil on canvas), by Weymouth, Mass.-based Elysia Johnson, in the New England Collective XII show at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Aug. 5-28.

Weymouth City Hall, built in 1928 and modeled after the Old State House in Boston, built in 1713.

Weymouth was settled by the English in 1622 as the Wessagusset Colony. That was before Boston (founded in1630) was established by the Puritans and after Plymouth (founded in 1620) was founded by the Pilgrims. The Wessagusset Colony was led by Thomas Weston, who had been a major financial backer of the Plymouth Colony. But the settlement was a failure because the 60 men from London who settled it were ill-prepared for the climate and other hardships there. Further, they lacked the religious drive of the Pilgrims. Wessagusset was founded on purely economic grounds and the 50-60 men there didn’t bring their families.

Bichman House, c. 1650, is likely the oldest surviving house in Weymouth though it looks rather like a modest suburban ranch house.

— Photo by Swampyank

Llewellyn King: The thrill of getting a human on the line; the ‘service economy’ is a giant con

Telephone operator circa 1900.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Something wonderful happened to me this week. I spoke on the telephone to a human being at a credit-card company. Well, not immediately. That would be too much to expect.

I had to go through some of the hoops of the company’s automated phone system, beginning with (as it always seems to) “Listen carefully because our menu has changed.”

And, of course, I had to enter the card number, the PIN, the last four digits of my Social Security number and my maternal grandmother’s name, and learn that for quality purposes my rising frustration was being recorded.

I explained repeatedly to the recording what I needed. It wasn’t having any of it. If it was a sample of artificial intelligence, it was acting more like artificial stupidity.

Finally, the AI device decided that stupid people – me -- weren’t worthy of its recorded messages and transferred me to a “representative.” Banks, credit- card companies, and insurance offices don’t have people; they have “representatives.”

This representative was smiley-voiced and delightful. She also was human. After 20 awful minutes of hearing a recorded voice (“How can I help you? I did not get that. Push 7.”), here was someone who really wanted to help. Hallelujah!

Try talking to a live person, you will like it. It is wonderful. She told me about the weather where she was, San Antonio, and we had a whale of a time doing something that I forgot people can do with a telephone: small talk. In a trice, she took care of my need.

I am a regular panelist on a weekly Texas State University webinar. A super-smart man, a polymath, suggested there that my problem for not reveling in the new isolation -- working from home, talking to machines, sending texts, rather than speaking on the telephone and emailing -- may be generational. This I take to be a nice way of saying that if people had sell-by dates, I am past mine.

The implication is that there is a superior place where the digital people do digital things, and pity those of us who do not do digital things, like eat, drink, fall in love. No less a person than the actor Meryl Streep said, “Everything that truly makes us happy is quite simple: love, sex and food.” If she likes talking, too, I will award her my personal Oscar. Another endearing Meryl quote is, “Instant gratification is not fast enough,”

There is one place where computers have not infringed on the old way of doing things: The U.S. Department of State. I believe that they are still looking up things in giant ledgers and writing by hand on parchment.

I say this because if you, dear citizen, wish to get a passport renewed, the expedited route at your local passport office takes five to seven weeks. I am waiting in apprehension for my renewal, having paid $200 for the super-slow “expedited service.”

You can get a replacement Social Security card in moments, a driver’s license immediately, but the State Department will have none of that.

Oddly, passports are issued to all except those with unpaid child support or outstanding criminal warrants. There are more reasons to deny a driver’s license than a passport. But the wheels at the State Department grind extremely slowly, and time isn't an issue.

The service economy has been a giant con, dreamed up by MBAs to keep customers at a distance or to dehumanize them so that they forget that they pay for the abuse they receive, whether it is from the passport office or some financial institution.

I frequent one gas station, in Scituate, R.I., where they still pump your gas. Night and day, there are lines of motorists waiting for fill-ups, and to have a few cheery words with the pump jockeys. Human contact, real service, seems to be worth a few cents more a gallon.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Hope Dam on the Pawtuxet River in Scituate

Blue gold

Horseshoe crabs mating. Horseshoe crabs live primarily in and around shallow coastal waters on sandy or muddy bottoms. They tend to spawn in the intertidal zone at spring high tides.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

When I was a small boy living along Massachusetts Bay, we used to pick up and fling those brown, helmet-shaped and scary-looking, but harmless, arthropods on the lower beach called horseshoe crabs into the water and sometimes even at each other. Little did we know that this species, which goes back almost half a billion years, would become an important bio-medical resource, so much so that, along with habitat destruction, including ocean acidification caused by man-made global warming from burning fossil fuel, the species is endangered in many places.

Horseshoe crabs, by the way, are not crabs. Rather, they’re related to spiders and other arachnids.

For some years, drug companies have been harvesting the bluish blood of the creatures in New England and other places on the East Coast for a protein that’s used to identify dangerous bacteria during new-drug testing, including vaccines.

So important is horseshoe-crab blood that its value is estimated to be $15,000 a quart.

While pharm companies assert that most horseshoe crabs survive after they’re milked and then returned to the water, many die as a result, and over-harvesting is a distinct threat to the future of the species. Of course, everything in nature is connected and wiping out horseshoe crabs will imperil other species.

Consider that they play an important role in the food web for migrating shorebirds, finfish and Atlantic loggerhead turtles.

So let’s hope that environmental regulators pay close attention to the horseshoe-crab population.

They remind us that, with ever-developing scientific knowledge, some previously mostly ignored species turn out to be very important to people and to the wider web of life that humans depend on – a web that people are destroying at an accelerating rate. The more species we can save, the better for us.

Even horseshoe crabs’ eggs are bluish.

Should have stopped at town?

State Street, Boston, in 1801.

“It was a very charming, comfortable old town — this Boston of uncrowded shops and untroubled self-respect, which, in 1822, reluctantly allowed itself to be made into a city.’’

—Mary Caroline Crawford (1874-1932), in Romantic Days in Old Boston

Embracing the nerd persona

“Cloudy Sheets,’’ by Tewksbury, Mass.-based artist Fernando Fula, in the group show “The Bold & Beautiful,’’ at the Hopkinton (Mass.) Center for the Arts through Aug. 26. The show was put together by Randolph, Mass.-based artist Jamaal Eversley

The arts center says the show “is about addressing who we are, what we stand for and how we allow other people's perception of us to affect how we see ourselves….”

“Eversley was teased and called a nerd when he was younger and was compared to Urkel (a nerdy fictional TV character). He now embraces his nerd persona and created abstract art about a character he calls ‘the nerd.’ He took a negative situation and turned it into a positive one and now shares that story with teens and adults through his “The Bold & Beautiful’’ art and writing workshops. It is about self-love, anti-bullying and perception.’’

Canoes on the Concord River (famous in literature — Thoreau, etc.), which borders Tewksbury on the southwest.

Dare to stare back

“Lemonhead in The Garden (In Spring)’’ (oil on paper), byEric Helvie, in the 16-person show “At Face Value,’’ at Cove Street Arts, Portland, Maine, through Aug. 27

The juror Vincent Maxime Daudin selected works that "reflected the multiple layers of 'worth' behind every single personality, from their current monetary appraisal to their timelessly emotional quality." The gallery says: “The portraits in this show look right back at viewers and dare them to engage as though they are looking another human in the eyes.’’

Judith Graham: In Maine and elsewhere, many elderly struggle to pay for basic necessities

Farmer's market in Monument Square, downtown Portland

— Photo by vBd2media

Townhouses in Portland’s West End, completed in 1835

— Photo by Motionhero

PORTLAND, Maine

Fran Seeley, 81, doesn’t see herself as living on the edge of a financial crisis. But she’s uncomfortably close.

Each month, Seeley, a retired teacher, gets $925 from Social Security and a $287 disbursement from an individual retirement account. To make ends meet, she’s taken out a reverse mortgage on her home here that yields $400 monthly.

So far, Seeley has been able to live on this income — about $19,300 a year — by carefully monitoring her spending and drawing on limited savings. But should her excellent health worsen or she need assistance at home, Seeley doesn’t know how she’d pay for those expenses.

More than half of older women living alone — 54% — are in a similarly precarious financial situation: either poor according to federal poverty standards or with incomes too low to pay for essential expenses. For single men, the share is lower but still surprising — 45%.

That’s according to a valuable but little-known measure of the cost of living for older adults: the Elder Index, developed by researchers at the Gerontology Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Boston.

A new coalition, the Equity in Aging Collaborative, is planning to use the index to influence policies that affect older adults, such as property tax relief and expanded eligibility for programs that assist with medical expenses. Twenty-five prominent aging organizations are members of the collaborative.

The goal is to fuel a robust dialogue about “the true cost of aging in America,” which remains unappreciated, said Ramsey Alwin, president and chief executive of the National Council on Aging, an organizer of the coalition.

Nationally, and for every state and county in the U.S., the Elder Index uses various public databases to calculate the cost of health care, housing, food, transportation and miscellaneous expenses for seniors. It represents a bare-bones budget, adjusted for whether older adults live alone or as part of a couple; whether they’re in poor, good or excellent health; and whether they rent or own homes, with or without a mortgage.

Results from the analyses are eye-opening. In 2020, according to data supplied by Jan Mutchler, director of the Gerontology Institute, the index shows that nearly 5 million older women living alone, 2 million older men living alone, and more than 2 million older couples had incomes that made them economically insecure.

And those estimates were before inflation soared to more than 9% — a 40-year high — and older adults continued to lose jobs during the second and third years of the pandemic. “With those stressors layered on, even more people are struggling,” Mutchler said.

Nationally and in every state, the minimum cost of living for older adults calculated by the Elder Index far exceeds federal poverty thresholds, which are used to calculate official poverty statistics. (Federal poverty thresholds used by the Elder Index differ slightly from federal poverty guidelines. Data for each state can be found here.)

One national example: The Elder Index estimates that a single older adult in good health paying rent needed $27,096, on average, for basic expenses in 2021 — $14,100 more than the federal poverty threshold of $12,996. For couples, the gap between the index’s calculation of necessities and the poverty threshold was even greater.

Yet eligibility for Medicaid, food stamps, housing assistance and other safety-net programs that help older adults is based on federal poverty standards, which don’t account for geographic variations in the cost of living or medical expenses incurred by older adults, among other factors. (This isn’t an issue for older adults alone; the poverty measures have been widely critiqued across age groups.)

“The poverty rate just doesn’t cut it as a realistic look at the struggles older adults are having,” said William Arnone, chief executive officer of the National Academy of Social Insurance, one of the new coalition’s members. “The Elder Index is a reality check.”

In April, University of Massachusetts researchers showed that Social Security benefits cover only a fraction of what older adults need for basic living expenses: 68% for a senior in good health who lives alone and pays rent and 81% for an older couple in the same situation.

“There’s a myth that Social Security and Medicare miraculously take care of all of people’s needs in older age,” said Alwin, of the National Council on Aging. “The reality is they don’t, and far too many people are one crisis away from economic insecurity.”

Organizations across the country have been using the Elder Index to convince policymakers that older adults need more assistance. In New Jersey, where 54% of seniors are economically insecure according to the index, advocates used the data to protect property-tax relief programs for older adults during the pandemic. In New York, where nearly 60% of seniors are economically insecure, advocates persuaded the legislature to raise the Medicaid income eligibility threshold.

In San Diego, where as many as 40% of seniors are economically insecure, Serving Seniors, a nonprofit agency, persuaded county officials to use pandemic-related stimulus payments to expand senior nutrition programs. As a result, the agency has been able to double production of home-delivered meals, to more than 1.5 million annually.

Officials are often wary of the financial impact of expanding programs, said Paul Downey, president and CEO of Serving Seniors. But, he said, “we should be using a reliable measure of economic security and at least know how well the programs we’re offering are doing.” By law, California’s Area Agencies on Aging use the Elder Index in their planning process.

Maine is No. 5 on the list of states ranked by the share of seniors living below the Elder Index, 56%. For someone in Fran Seeley’s situation (an older adult who is in excellent health, lives alone, owns a house, and doesn’t pay a monthly mortgage), the index suggests $22,560 a year is necessary — $3,200 more than Seeley’s annual income and $9,500 above the federal poverty threshold.

Fran Seeley’s income — from Social Security, a retirement account, and a reverse mortgage — comes to about $19,300 a year. With inflation increasing, “it means I have to cut back in any way I can,” Seeley says.

A look at Seeley’s budget reveals how quickly necessary expenses accumulate: $2,041 annually for Medicare Part B (this is deducted from her Social Security check), $4,156 for property and stormwater taxes, $390 for home insurance, $320 for furnace cleaning, $1,440 for heat, $125 for water, $500 for gas and electricity, $300 for property maintenance, $1,260 for phone and Internet, $150 for car registration, $640 for car insurance, $840 for gasoline at current prices, $300 for car maintenance, and $4,800 for food.

The total: $17,262. And that doesn’t include the cost of medications, clothing, toiletries, any kind of entertainment, or other incidentals.

Seeley’s great luxury is caring for four cats, which she describes as “the light of my life.” Their annual wellness checks cost about $400 a year, while their food costs about $1,080.

With inflation now making her budget even tighter, “it means I have to cut back in any way I can. I find myself going into stores and saying, ‘No, I don’t need that,’” Seeley said. “The biggest worry I have is not being able to afford living in my home or becoming ill. I know that medical expenses could wipe me out in no time financially.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News Reporter.

David Warsh: 'Depreciation,' 'development' and 'inflation'

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Everyone knows that the cost of living has risen significantly in the past 75 years — recently, at rates not seen since the early ‘80s. To understand a little better why this has is happening, try this simple trick: Think of rising prices as a matter of the depreciation of the dollar against the prices of goods and services, instead of “inflation.” That won’t make the experience any less disorienting than calling it by the headline term, but it will give you a better sense of how and why the problem has arisen.

What’s the difference? With “inflation,” the answer is implied by the question. The explanation is always the same: the governors of the Federal Reserve Board have been cavalier with interest rates. Too much money is chasing too few goods. “Depreciation,” on the other hand, permits you to think about events taking place in the real world that forced the Fed’s hand – events that monetarists commonly describe as “ad hoc.”

Certainly a great deal of “ad hoc” change has occurred in the real world since 1950, when a candy bar cost a nickel and a haircut could be had for $1.25. Very little of the momentum behind that history would seem to have originated with the Fed, the stringent tightening of monetary policy in 1979-’82 being the major exception.

The current episode of rapidly rising prices is associated with the governmental response to COVID; accelerated with outbreak of all-out war in Ukraine; deglobalization of supply chains; food shortages and the threat of famine; policies designed to slow climate change, and energy disruptions now said to rival the crisis of the early and mid ‘70s.

True, in the course of regulating the nation’s system of money and banking, the Fed had to react to these various afflictions. Sometimes its governors may have overreacted. Sheer monetary incompetence can have a place in the story, too: Look no farther than the central bank of Sri Lanka for an example of that.

In the main, though, dollar depreciation occurs in response to real-world problems. Severe interest-rate policy can arrest expectations of runaway prices, as in the ‘80s. But dollar depreciation occurs in response to real forces. Never in millennia has it been reversed in a currency that endured. Repeating the mantra that “‘inflation’ is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon” is just blowing hot air.

In The Cost of Living in America: A Political History of Economic Statistics 1880-2000 (Cambridge, 2009), Thomas Stapleford, of the University of Notre Dame, describe how we came to employ sophisticated price indices to measure rising prices. The construction of economic statistics makes a fascinating story, but Stapleford spends only two paragraphs on why the cost of living changes, accepted at face-value explanations of particular episodes advanced by economists: W. Stanley Jevons, in the 19th Century, and Irving Fisher, in the 20th. In each case, the economists asserted, when “the supply of money increased, its value would fall, leading to higher prices.” Hence the “inflation” of prices by an excess of money.

But what if it works the other way around? What if the “cost-push” argument is more often correct? What if the quantity of money increases because prices are rising? Every central banker knows it is not simply one or the other; it is both. But with “inflation,” you only see one side of the story – in most instances, the less important side.

We don’t know more because there exists no conceptual scheme of sufficient generality to organize all those various “ad hoc” explanations of rising prices under one heading. Whatever intuitive appeal has existed in the term “complexity,’’ “complexity” was already well on its way to becoming a magic word, an incantation, quite devoid of meaning.

The second mistake I made was failing to notice that economists already possessed a serviceable term of their own to describe this dimension of modern life. They called it “economic development,” words as familiar and easy to use as they were lacking in precision. To give it meaning to development, as opposed to “growth,” which is a matter of inputs and output, requires only linking back to one of the most fundamental categories in all of economic theory: the division of labor.

Easier said than done! Although the role of specialization in producing material well-being is clearly spelled out in the first three chapters of An in Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith quickly moves on to the analysis of a competitive system, and this is the tradition, taken up by David Ricardo and T.R. Malthus, that has dominated economics down to the present day. I was slow to figure this out.

There! After fifty years of writing about these topics, often clumsily, my two key mistakes are acknowledged, and I have set out here all I have learned: “depreciation” and “development” (understood as the extent of the division of labor) are better language than “inflation,” not to mention (here I blush) “complexity” and “conflation” in 1984.

For a glimpse of how things might yet be different, and probably will be before long, see “One Analogy Can Hide Another: Physics and Biology in Alchian’s ‘Economic Natural Selection’”, by Clément Levallois, which ultimately appeared in 2009 in History of Political Economy. (JSTOR access required). Or tune in to Nathan Nunn, now back at the University of British Columbia. But the biological analogy at the heart of the re-launch of evolutionary economics in the years after World Wat II is too wonky for this column.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Seven Hills Park at Davis Square, Somerville. The towers in the park each represent one of the city's original hills.

Islanders using everything they can from the sea

In this watercolor by William Hall, Block Islanders in the 19th Century are collecting fin fish, crabs and lobsters trapped in tidal pools. They also harvested large amounts of seaweed to be used for food and fertilizer. See photos below. This painting is part of an extensive series of watercolors Mr. Hall has done over the past decade of people at work.

He is represented by, among other venues, David Chatowsky Art Gallery, 47 Dodge St., Block Island, R.I. (401) 835-4623

One recipe for “seaweed pudding”:

Put a cup of dried seaweed in a pan and add a liter of whole milk.

Gently bring to boil and simmer for 10 to 15 minutes.

Strain through a fine sieve or a muslin cloth into a bowl and cool.

Put in a refrigerator to set for a couple of hours.

The harvesting of seaweed — mostly kelp — (including increasingly from aquaculture) for food and many other uses has greatly increased in the past few years. And seaweed aquaculture is more and more promoted for environmental reasons. For one thing, it absorbs some of the excess carbon dioxide put into the atmosphere by fossil-fuel burning. For another, seaweed — especially “kelp forests” — is a home for many species.

Collecting seaweed in locally made baskets.

Spreading seaweed as fertilizer on a Block Island farm.

‘Insecurity and surprise’

“Resonance” (encaustic painting), by Deborah Peeples, who has a studio in Somerville, Mass., and lives in neighboring Cambridge.

She writes in the New England Wax Web site:

“Painting is my sensual response to the world, a time-release recording of the sounds, smells, and intensity of a moment. Abstraction is a language that traces my inner turbulence and exuberance. The natural translucent materials of beeswax and damar contain a lush baroque beauty. Mixing pigments, playing with opacity, heating the panel, always touching, breathing the smell of the hot beeswax, brings a slowness and intimacy to the process. The work is layered, incised, inlaid, and scraped; lines cut into the surface, either sharp or blurred, feel alternately vulnerable and impenetrable. Humor and playfulness are found in the saturated, syncopated color and jostling shapes that play off an underlying grid. These juxtapositions create imbalance, insecurity, and surprise, a metaphor for the search to find my place in the world’’.

Harvard Square, in Cambridge

— Photo by chensiyuan

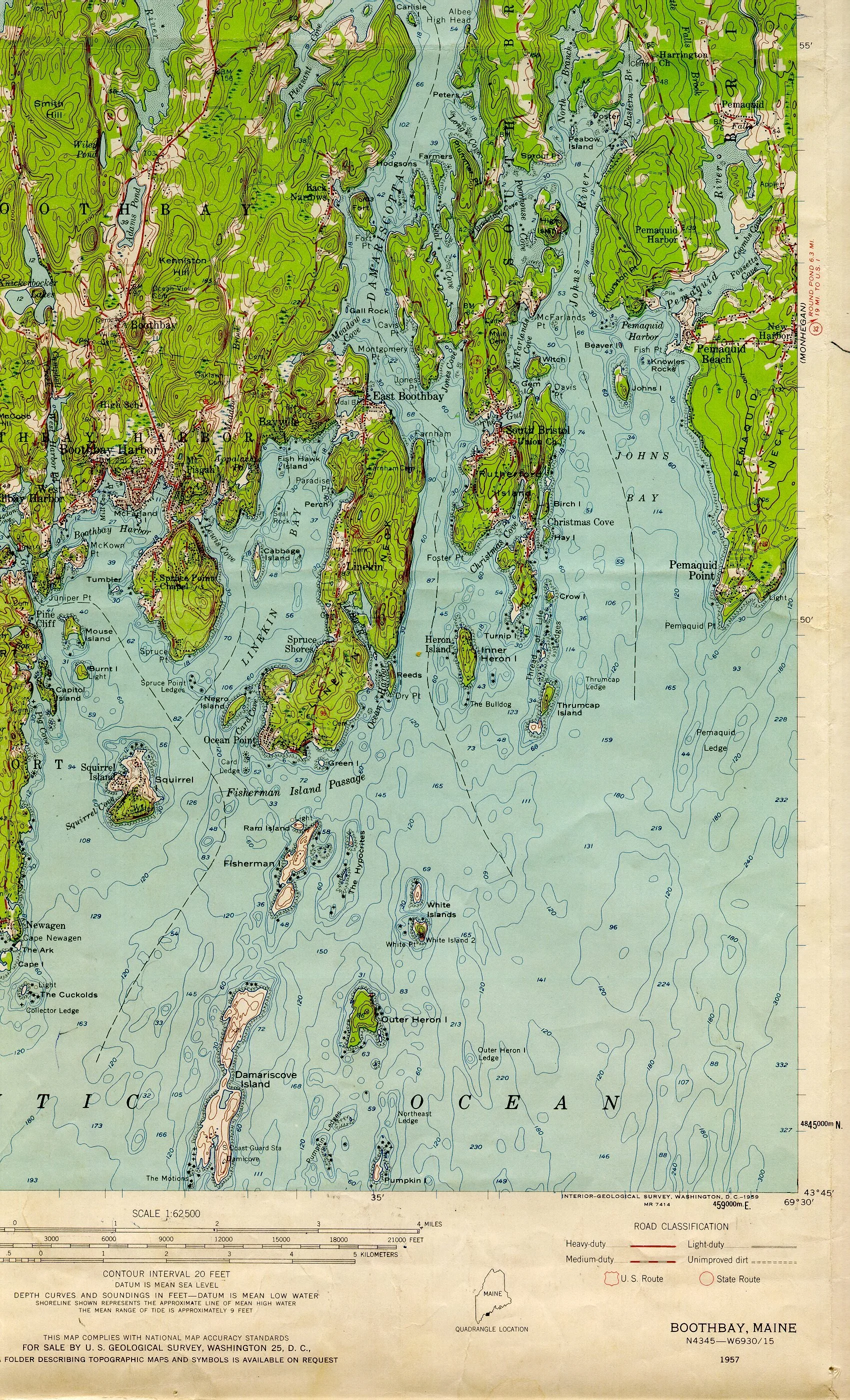

The stalactite coast

“The middle part of Maine, all the way from Bar Harbor to Portland, hangs down like stalactites that drip little islands into the Atlantic. It's divided by rivers and harbors with cozy names that sound like brands of bubble bath or places boats sink in folk songs.”

― Linda Holmes (born 1970), an American author, cultural critic and podcaster

xxx

“Portland could have been any city. Port Clyde was too uncluttered to be anything else. There is a reason Stephen King sets his stories in little Maine towns. They are too quiet to be believed wholly savory.”

―From Holidays With Bigfoot, by Thomm Quackenbush (born 1980), American author of horror, epic fantasy and contemporary fantasy.