Llewellyn King: Using low radiation to fight inflammation in COVID-19, other ills

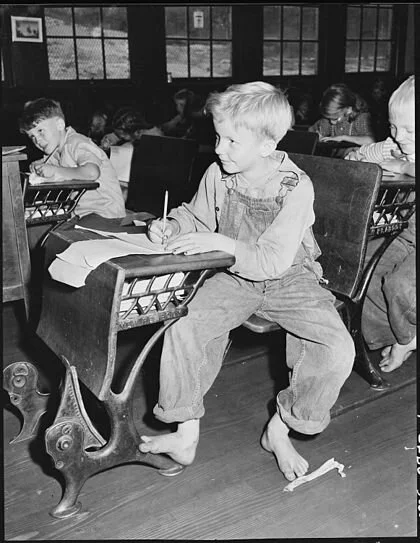

X-ray treatment of tuberculosis in 1910. Before the 1920s, the hazards of radiation were not understood, and it was used to treat a wide range of diseases.

A little boy was taken to the zoo in the New York City borough, where he was enthralled to ride Jalopy, a Galapagos tortoise. Jalopy became a favorite. But then one day the giant tortoise wasn’t there, and the little boy learned that she had cancer and had been taken to Arizona for radiation treatment.

“I had never heard of radiation,” said Dr. James S. Welsh, professor of radiation oncology at Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood, Ill. But his love of that tortoise was enough for him to devote his life to radiation therapy.

Now Welsh is in the vanguard of doctors who hope to save lives by using radiation as a therapy for patients with COVID-19 -- and possibly as a therapy for Alzheimer’s, arthritis and other diseases where inflammation plays a role.

Inflammation is present when the body’s immune system mobilizes to fight disease or injury. The problems come when the immune system, according Welsh and other doctors I have interviewed, goes “haywire.”

Radiation can’t cure COVID-19, Welsh explained, but it can be used to reduce the acute inflammation, known as cytokine storm. This causes a flooding of the lungs and is what kills most COVID-19 patients.

Using very low doses of radiation to fight respiratory inflammation isn’t new: It was how viral pneumonia was treated more than 75 years ago, before the perfecting of a battery of drugs which took over. Radiation was highly effective against viral pneumonia, with success rates recorded at 80 percent or better. Antibiotic drugs combined with growing public antipathy to radiation in all forms took it off the pneumonia therapy list.

But now it appears to be back-to-the-future time for radiation.

Welsh says that a patient about to enter acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which kills many COVID-19 patients, can be treated with low-dose radiation to clear the lungs. Afterward, the patient can return to the ward to get treatment with antiviral drugs. No ICU, no ventilator, no long-term scarring of the lungs.

“Radiation could be used with a drug like remdesevir or another drug, like steroids. But it is my opinion that radiation will prove superior to dexamethasone or other steroid medicines,” Welsh said in an interview with me on White House Chronicle, the PBS television program.

A few clinical trials of low-dose radiation therapy for COVID-19 have begun in the United States and six other countries, including Canada and the United Kingdom. “Although peer-reviewed results have yet to be published, preliminary data seem very encouraging, and certainly justify the siting of a proposed clinical trial here,” said Welsh, referring to the Hines Veterans Administration Hospital in Chicago, where he is the chief of radiation therapy. He hopes to launch a clinical trial there in weeks.

The radiation doses for COVID-19 treatment are extremely low. Welsh is planning to use .5 gray in his trial, but others use more, 1 gray or even 1.5 grays. Those are above X-ray doses, but well below cancer doses. Brain cancer and lung cancer patients get doses of 60 grays, with up to 80 grays for prostate cancer, Welsh said.

This doesn’t mean that there isn’t opposition.

Much of the concern over radiation is associated with the linear, no-threshold (LNT) model which posits that all radiation will have detrimental health effects even at minuscule levels, like normal background. This theory has been contested violently for decades by nuclear scientists, but it remains an undermining orthodoxy.

“Most people and physicians are not familiar with the potential application as an anti-inflammatory in infectious disease,” Welsh said.

Nonetheless, he believes that the future beckons. When I asked him about the use of radiation in other diseases where inflammation was a factor, particularly Alzheimer’s and arthritis, he responded, “A definitive ‘yes.’ ”

The beauty of radiation therapy, according Welsh and others I interviewed, is that about half the hospitals in the country have radiology departments and staff. Treatments for COVID-19 patients could begin almost immediately.

As to Jalopy, she died in 1983 at the age of 77. She was so popular over the 46 years she lived at the zoo that a bronze sculpture of a Galapagos tortoise was erected as a memorial.

And you might say, her memory radiates hope for the future.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Chants in Copley Square

Copley Square fountain, with the Old South Church’s tower in distance, in a recent, pre-pandemic summer.

— Photo by Caroline Culler

“There’s a poem in Boston’s Copley Square

where protest chants

tear through the air

like sheets of rain,

where love of the many

swallows hatred of the few.’’

— From “In This Place (An American Lyric)’’, by Amanda Gorman

Police brutality

“Expired Meter’’ (oil on board) by George Hughes (1907-1990), at the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport

(c) 2020 National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI, and the American Illustrators Gallery, New York, NY

Mr. Hughes lived for the last part of his life in Arlington. Vt., between the Taconic Range and the southern Green Mountains, where one of his neighbors for some years was the far more famous illustrator Norman Rockwell, who eventually moved to Stockbridge, Mass., in the Berkshires.

Fog over the Battenkill River in West Arlington, Vt.

New England's COVID confusion

Maine Gov. Janet Mills

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Most of us are getting pretty claustrophobic these days and can’t travel long distances. But at least we New Englanders have plenty to see in our compact region – beautiful mountains and coasts, lovely lakes, innumerable historic sites, great food, bucolic empty COVIDized college campuses….

The biggest regional travel hurdle at this point: Maine Gov. Janet Mills fears people from Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Citing the high percentage of people from those two states who have tested positive for COVID-19, she has ordered that Rhode Islanders and Bay Staters must quarantine for two weeks or present proof of a recent negative virus test to be legally in the Pine Tree State. The effect is to discourage many, perhaps most, of these people from going to Maine – a big blow to its tourist industry, though many ignore the order, with some anxious “illegals’’ sneaking into the state via back roads from its deeply rural western side.

Vermont also has tough rules, but somewhat different – they want to know what county you come from, not just the state, in determining whether you need to quarantine.

Has there been a lot of sneaking across state lines? Complex times indeed. Maybe we need a special meeting of New England governors – three un-Trumpian Republicans, three garden-variety Democrats -- to sort out the confusion and come up with a truly regional plan. All the region’s governors are calm, competent and respectful of science. It’s curious that the most liberal part of the country has three GOP governors, though they would hardly be considered in the mainstream of the party, though New Hampshire’s Chris Sununu comes rather close.

Anyway:

Harvard’s Dr. Ashish Jha, incoming dean of Brown's School of Public Health, has famously praised Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo’s tough response to the pandemic: "Rhode Island has done a fabulous job -- I would say one of the kind of standouts in the country, a model for how we should be doing this," Dr. Jha told WPRI TV. "If the rest of the country had done what Rhode Island has done, we'd been in a very different place as a nation." And yet Rhode Island testing data led Governor Mills to her rather draconian order. Without a unified and coordinated federal response to the pandemic, including how to conduct and promptly report test results and do speedy contact tracing, the policy confusions will continue as everybody tries to interpret the latest data, based on different states’ practices.

To read Dr. Jha’s remarks, please hit this link.

For a good review of America’s COVID-19 testing failures, please hit this Bloomberg link

The article notes:

“Test results, to be useful, should arrive in less than two days. If they take longer, opportunities to isolate infected people and trace their contacts with others wither, undermining broader containment efforts. So why can’t the wealthiest and most innovative country in the world have more rapid-fire testing during a pandemic?’’

A time and place for tweed

Put on before leaving your room at Yale.

{As a Yale freshman Calvin} Trillin showed up in New Haven {in 1953} in awe. “People looked like they had costumes on — tweedy sports coats, patches on the elbows. I’d never seen things like that.’’ And of course, he saw men’s costumes because the faculty was certainly a male bastion and so was the student body. In those days, Yale was not a study in diversity.’’

— From Lary Bloom, in “A Yale Education,’’ in the March 22, 1998 Hartford Courant.

Sophia Paslaski: Supreme Court just made the case for Medicare for All

From OtherWords.org

People of the menstruating persuasion: how dare you. The highest court in the land demands to know.

This July, the Supreme Court of the United States decided that President Trump, who does not have a uterus, was quite right to object to Obama-era rules under the Affordable Care Act that allowed Americans who do have uteri access to free birth control through their employer-provided health-insurance plans.

Specifically, NPR reports, the Supreme Court upheld a Trump administration rule that “would give broad exemptions from the birth control mandate to nonprofits and some for-profit companies that object to birth control on religious or moral grounds.”

Not just religious — “moral.”

So even if Jesus is cool with it, if you have personal “moral” quandaries with the people in your employ taking birth control, you’re free to cut your workers off from essential medications.

And I do mean absolutely essential. While some of us use ACA-covered birth control like “the pill” or an intrauterine device (IUD) as an optional measure to prevent pregnancy, many of us depend on it to treat hormonal conditions.

Birth-control medication is commonly used to help manage premenstrual syndrome and painful periods. Doctors prescribe it to control the growth of painful ovarian cysts that can lead to life-threatening complications if left untreated. It helps those with challenges like depression level out the hormonal fluctuations that can trigger cyclical mood changes around menstruation.

And for one in 10 of us, it is the best line of defense, short of surgery, against endometriosis, a debilitating condition that many struggle to manage without birth-control medication.

But perhaps that’s not the point.

Plenty of us have made this medical appeal before to no avail. Medicine doesn’t seem to matter to those employers who deem themselves religiously or morally opposed to “providing” birth control to their employees — as if employers are handing out pill packs at the reception desk like free swag at Comic Con.

Maybe, as always, this is about the medical-industrial complex.

In this country, where much health insurance is tied to employment, employers often take the position that they are “giving” their employees health care — and therefore, that they are entitled to some say over what that care entails.

That’s nonsense — but so is tying health care to employment in the first place.

Politicians who oppose Medicare for All like to cite the concerns of voters who, allegedly, love their employer-provided health insurance. But this court decision proves what most of us, I expect, already know: private health insurance isn’t all that great.

It doesn’t cover everything you need it to cover. It’s beholden to the whims of the employers who provide it. It’s expensive for the self-employed who purchase it on their own. It prioritizes profit over care, yet still never seems to get the billing done right.

As Sen. Elizabeth Warren said at a debate last year, “Let’s be clear: I’ve never actually met anybody who likes their health insurance company.”

So fine. Refuse to offer health-insurance plans that cover birth control, if you must. I’m not happy about it, especially as I write this an hour before an appointment with my OBGYN to talk about birth control and endometriosis.

But I won’t fight you either, because I think you’ve done my fighting for me — I can think of no better argument for Medicare for All than the freeing of the noble employer from the dreadful moral quandary of birth control.

Great job, team. Drinks are on Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

Sophia Paslaski is on the staff of the Institute for Policy Studies.

Unprofessional clamming

— Photo by Invertzoo

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

In one part of my brain it’s endless summer, as I was reminded by Dr. Ed Iannuccilli’s recent column in GoLocal about crabbing as a kid on the Rhode Island shore. (Hit this link to read the doctor’s sweet essay: https://www.golocalprov.com/articles/dr.-ed-iannuccilli-crabbin-on-a-summer-evening)

My paternal grandparents lived in a gray-shingle house on West Falmouth Harbor, on the Cape side of Buzzards Bay. (The house has since been torn down and replaced by a monstrosity twice as high.) The harbor once had vast numbers of quahogs and more than a few oysters, too. We kids would wade out on the flats, collect the shellfish in a bag and bring them back to a stone dock, where we’d smash them to get at the meat, over which we’d squeeze a lemon, and eat right there. Very messy and unprofessional. This was before our father showed us how to open them with a special knife, which I don’t think I could do now. I fuzzily remember that he could do it with one hand, and with a cigarette dangling from his mouth.

On those seemingly open-ended days, a southwest wind was always blowing off Buzzards Bay, the air was always about 76 degrees, as was the water, and the haze turned into a purple fog in the late afternoon as the catboats and the bluefish and striped-bass seekers returned to the harbor from the usually choppy open bay.

A big oil spill in 1969 closed the harbor to legal shellfishing for decades. (Still, people, especially poor immigrants from Southeast Asia, would come clamming anyway and probably lied to the stores and restaurants about where their shellfish came from). But something good came from the disaster: West Falmouth Harbor became an internationally known place for research into the effects of oil spills and how to remediate them, in large part because the Marine Biological Laboratory was just down the road, in Woods Hole.

I’ll always remember the late ‘50s under a hazy sun as I dug into the sand to pull out a delectable quahog.

Fog in SoWa

“Luceombra’’ (Ink & gouache on cotton paper) by Sabrina Garrasi, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston. Hit this link.

In SoWa in happier, pre-pandemic days

Lanoue Gallery is in The SoWa Art & Design District (South of Washington Street) in Boston’s South End. It’s a community of artist studios, contemporary-art galleries, boutiques, design showrooms and restaurants in what was once an area of neglected warehouses. It features the SoWa Open Market, the SoWa Vintage Market and a now-fashionable residential neighborhood.

'The opposite of today'

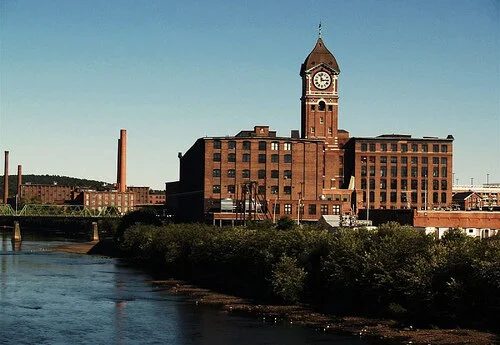

The Ayer Mill in Lawrence

“Don’t even try looking for him where he grew up

in Lawrence, Mass. The whole town is burning.

The remarkable thing about tomorrow is that everything is

the opposite of today. The shadow that now stalks you

becomes your confessor….’’

— From “No Fault Love,’’ by Richard Jackson

Leonard Yui: Pointers on setting up fresh air classrooms

The main quad of Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

The early science is showing that outdoor spaces are safer than indoor spaces for COVID-19. One research study from Japan found that COVID-19 transmission was 18.7 times greater indoors than outdoors. Another article from China found that, of 7,300 active COVID-19 cases, just one was connected to outdoor transmission.

Indoor spaces were never designed for social distancing and many are now depending on aging climate- controlling systems for viral filtration. These limitations are now muddied by politics, finance, marketing and logistics, raising the urgency to consider safer options.

Outdoor classrooms, too, have limitations compared to their indoor counterparts. What do we do about the sun, cold, heat, rain, etc., especially in New England? And where do we place the projectors, desks, seats, etc.?

It seems unthinkable to allow students and teachers to be exposed to the elements, but in 1907, Providence did just that by experimenting with the first “fresh-air” schools in the U.S. to combat the tuberculosis epidemic. Pioneered by two women doctors, the idea was to open an entire classroom wall to the frigid New England winters and bundle the students up with sleeping bag-like sacks with heated stones. It was so successful at reducing the health risks that it triggered a movement across the nation that lasted for nearly 50 years. Many advocates today, backed by recent science, are trying to bring these methods back.

The “fresh-air” classroom movement gives us a model for opening school while managing the elements with such devices as tents, umbrellas, heaters, jackets and so on. What may be lost by focusing overly on environmental and spatial adjustments is how pedagogy also can change landscapes. The proposed six-foot plots are more than just a measure of distance between two people, but a reflection of a complex non-classroom world wrestling with issues of health, race, wealth and climate inequities. The move outdoors is also a metaphor for adapting our beings to wild variables of society and to engage, first, those social and ecological issues that are near—that directly touch us.

Outdoor spaces can be mocked up like traditional classrooms, but they can offer more because of the COVID-19 restrictions. Safer outdoor places permit more opportunity for student interactions, larger spaces allow for groups to form personalized patterns, and the natural elements provides a dynamic background for interaction. Digital assets could supplement these offerings by having students pre-download slide presentations and use their phones as mini-projectors. By extending wifi signals, students could use Zoom as a video/audio connection, and digital tablets could serve as whiteboards.

On a more imaginative path, the lack of walls, roofs and boundaries mean the class is not confined to a location or simple desk patterns. The field of environmental education recommends using outdoor experiences as part of developing broad individual awareness of “how people and societies relate to each other and to natural systems.” A philosopher-colleague reminded me that the Ancient Greeks preferred talking and sharing their thoughts while going on long walks. Using the “Socratic method” with a walk-and-talk method might encourage students to make links between course topics and physical locations that have specific meaning for them. In the business world, professionals often do key “business” transactions in transitionary (between meetings) or relational (like dining) interactions.

None of this is a substitute for the traditional indoor classroom, but the current circumstances beckon more creative negotiation among places of safety, convenience and learning. Simply going outdoors is one step, but another more enticing and sustainable direction is to reshape the celebration of pastoral landscapes to places that connect us more deeply to the outside world, both figuratively and literally. These changes can be small, sporadic and scattered around many places, but in aggregate, and over time, they should make a valuable impact to safety and culture and promote a more animated learning place.

Leonard Yui is an associate professor of architecture at Roger Williams University, in Bristol, R.I.

Hit this link to see Professor Yui’s plan.

Another Mainiacal gift

Successful fisherman at Oak Point Camps, Portage Lake, Maine, around the turn of the 20th Century

“A Maine fishing camp! The state that’s given American culture the lumberman, the lobsterman, the Maine Guide, has also given this: the camp in the woods where the trout bite even faster than the black flies, the salmon leap into your canoe of their own volition, the griddle cakes come stuffed with blueberries, the loon calls at night, the moose bellows, and you sleep soundly under thick wool blankets even in July.’’

-- W.D. Wetherell, in One River More

David Warsh: The past and future of U.S. multiculturalism

Satellite view of Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, D.C.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.,

A syllogism printed on a series of placards that I pass every day on my way to work says this: “If you believe that all lives matter, you are right/ all lives should matter/ but all lives can’t matter/ until Black lives matter/ to everyone.” I’ve wondered since I saw it first, what can be said about how Black lives changed in the half-century between the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in 1968, and the murder of George Floyd, in 2020?

I wanted a survey. I’ve read several good books about those years, including Fault Lines: A History of the United States since 1974 (Norton, 2019), by Kevin Kruse and Julian Zelizer; and Age of Fracture (Harvard Belknap, 2011) by Daniel T. Rodgers. I tried to make a survey that might satisfy a Sunday reader, using Rodgers. I ran out of steam below as I reached the so-called “War on Drugs” and the incarceration mania that accompanied it, lacking a source on the subject as dependable as is Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, on the opioid epidemic that followed.

All American lives change periodically, in Rodgers’s view, and then change again, in accordance with deep social currents of intellectual life. The self-reliant individual celebrated in one century is seen in the next to be forged by social pressures – caste, class, race, “the system.” Ages change every two or three generations, usually in opposition to the age that went before.

The years after the Great Depression and World War II witnessed one of these periodic shifts, Rodgers says. “Conceptions of human nature that in the post-World War II era had been thick with context, social circumstance, intuitions and history gave way to conceptions of human nature that stressed choice, agency, performance, and desire…. Notions of structure and power thinned out… The last quarter of the [20th] century was an era of disaggregation, a great age of fracture.”

It was not that people ceased banding together in time. “In an age of Oprah, MTV and charismatic religious preaching, the agencies of socialization were different from before. What changed across a multitude of fronts were the ideas and metaphors capable of holding in focus the aggregate aspects of human life as opposed to its smaller, fluid, individual ones.” Theaters of daily life that Rodgers examined include industrial organization, gender politics, rival conceptions of power and community, the role of history, and, of course, race.

In racial politics, Rodgers’s sense of fracture began with the retreat from busing schoolchildren from one school district to another as a means of addressing age-old patterns of residential segregation. Private “academies” blossomed, especially in the South. Government housing projects such as the Pruitt-Igoe development, in St. Louis, and Chicago’s Robert Taylor Homes were demolished. The Community Redevelopment Act of 1977 privileged ownership over rental housing.

African-American leaders sought “parity” under the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Massive voter-registration drives produced the first Black mayors in Detroit, Chicago, Atlanta, Philadelphia, New York, New Orleans and Birmingham, Ala. Universities established African-American Studies programs. There was a new Black presence in public life: authors Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Maya Angelou; television series Sanford and Son, All in the Family, The Cosby Show and, especially, Alex Haley’s mini-series Roots. Eventually, Hollywood filmmakers Spike Lee and Jordan Peele became major figures.

With the late ’70s and ’80s, the pace of change accelerated – the “color-blind” inversion followed, and the first challenges to affirmative action. Awareness grew of the increasing heterogeneity of America’s racial composition: Hispanic-Americans, Asian-Americans, Pacific-Americans. And all the while, the periodic riots after beatings or killings or the acquittal of those who committed them. “In a liberation that was also the age’s deficit, a certain loss of memory has occurred,” wrote Rodgers – in 2011.

I return to Age of Fracture regularly because Rodgers’s acuity accords so well with the various notions of political cycles in American history that have been around practically since the nation’s history began – stories of involvements shifting between public purpose and private interests, centralization and pluralism, each phase growing out of the contradictions of the one before, producing a zig-zag pattern.

So what might we hope for the next 50 years? We’ve done pretty well to this point. I can’t think of a better answer than “More of the same.” Multiculturalism, including the legacy of slavery, poses no challenge that Americans cannot surmount.

. xxx

For a 40-minute tour of another rights revolution of the 20th Century, watch Journey across a Century of Women, Claudia Goldin’s Feldstein Lecture, delivered last week to the all-virtual Summer Institute of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Goldin, of Harvard University, is finishing a book on the subject, which will receive much attention when it appears. If you are at all curious about the strains imposed on working women by the COVID-19 pandemic, watch her lecture now.

. xxx

Emmanuel Fahri, 41, of Harvard University, died last week, apparently by his own hand. It was the fourth such death of a prominent economist in a year, following those of Martin Weitzman, also of Harvard; Alan Krueger, of Princeton University; and William Sandholm, of the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Jill Richardson: Trump’s quasi-dictatorship is ill-suited to a pandemic

Strong leaders!

From OtherWords.org

The Trump administration is apparently undertaking its latest effort to make 2020 more of a Kafkaesque nightmare than it already is. Yes, we’ve got murder hornets and a swarm of flying ants that can be seen from space over in Ireland, but maybe the scariest plague of the year is the president.

Since the start of the pandemic, Trump’s only concern has been his poll numbers. He wants to go back to the reality we left behind in 2019: an open economy and no mass casualties from a novel virus.

We can’t do that, so he’s done his best to pretend: downplaying the pandemic, falsely claiming that his administration has it under control, urging a quick economic reopening, and inaccurately claiming the economy is strong anyway.

When he can’t pretend everything is fine, he blames the Chinese. But China is not responsible for Trump’s botched response to the pandemic.

Now the Trump administration is actively interfering with the pandemic response.

Hospitals have been instructed to send COVID data to a central database in Washington, bypassing the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The information will no longer be accessible to the public, raising concern that the data is being hidden for political reasons and the lack of transparency will make it easier for the administration to mislead the public.

The administration is also blocking CDC director Dr. Robert Redfield from testifying before Congress about the safety of reopening schools. They are attempting to block GOP senators from allocating billions of dollars to the CDC, Pentagon, and State Department for pandemic response. And the administration even opposes sending billions to states for testing and contact tracing.

Trump’s message to states has largely been “you’re on your own,” declining a national leadership role and placing responsibility for handling the pandemic on the states. He’s also suggested that governors should “treat him well” to receive federal aid, using the pandemic as a bargaining chip to silence dissent from governors who disagree with him.

Earlier in the pandemic, when personal protective equipment (PPE) supplies were limited, the federal government was even seizing PPE shipments.

In normal times, I would say the president should not be abdicating his leadership responsibility on the pandemic response. Under this president, I think we’re all better off if he and his political appointees interfere as little as possible and let more capable people do their jobs.

Despite his recent conversion to mask wearing, Trump’s authoritarianism is ill-suited to a pandemic. You cannot lower mortality rates by claiming the pandemic is under control and trying to force schools and businesses to reopen, regardless of the risk to workers. You can’t prevent the economy from tanking by insisting that it’s fine.

Trump’s top concern appears to be his own approval ratings, not our national welfare. He seems to believe his denial will be enough to save the economy — a plan that will fail and cause further mass casualties along the way.

The administration has created a terrible situation. All of our choices between our health and our economy are tough, and no choices will fully protect us. More than 145,000 people have died, and our economy is a mess.

We need to govern with facts instead of fantasy. If Trump can’t handle the job, he should get out of the way.

Jill Richardson is a sociologist.

Still thirsting

“The grass resolves to grow again,

receiving the rain to that end,

but my disordered soul thirsts

after something it cannot name.’’

— From “August Rain, after Haying,’’ by Jane Kenyon (1947-1995), a poet who lived with her husband, Donald Hall (1928-2018), also a poet, in very rural Wilmot, N.H.

Rationing words

Lubec, at the eastern end of Maine

— Photo by Ken Gallager

“The Maine Yankee is not nearly as taciturn as a stranger might at first consider him, but it is a rule that words are not to be wasted.’’

— From WPA Maine: A Guide “Down East’’ (1937

Downeast Maine is in red.

Brother Jonathan, an old historical national personification of New England

It means what you say it means

“Mobius’’ (painted black cherry), by Jeremy Holmes, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston

Chris Powell: Perfect safety is impossible! Reopen schools

Hard as he tries, Connecticut Gov. Lamont can't guarantee safety to anyone as he undertakes to get the state operating normally again with the virus epidemic diminishing. Largely because of the governor's use of emergency powers, Connecticut is doing far better than other states, but some people are still scared -- and some seem to see financial advantage in staying scared.

So the governor's plan for reopening schools with conscientious precautions is meeting much resistance from the Connecticut Education Association -- the big teacher union -- as well as U.S. Rep. Jahana Hayes, D-5th District, a former national teacher of the year and teacher union member. While young people are far less susceptible to the virus than others and most medical experts endorse resuming school, the teachers want a guarantee of perfect safety before going back to work.

The governor can't provide such a guarantee because there isn't any, and if teachers require one, they should stay home -- under their beds even, forever even.

Connecticut's teachers are well paid, enjoy summers off and great job security, and lately have been working much less if at all while still getting paid as usual, even though "distance learning" has been a flop. So their insistence on a guarantee of safety before returning to work is beyond arrogant while, quite without guarantees, supermarket employees work every day to keep them fed, postal workers work every day to keep them supplied, and police officers work every day to guard them against predators, whose numbers are growing as society steadily disintegrates.

If education is as crucial as the teacher unions maintain when they demand raises, it's just as crucial when children have lost a semester and many parents have incurred big daycare costs. So the CEA should stop distributing those lawn signs congratulating its members as if they are hospital workers fighting the virus and instead urge teachers to do something worth congratulation.

KEEP COPS IN SCHOOLS: Accompanying the clamor to "defund the police" or at least order them to stop enforcing laws the underclass doesn't want to obey is clamor to eliminate what are euphemistically called "school resource officers," These police were placed in schools so someone besides a burly gym teacher could respond quickly to violence and other disruption by students, since, short of murder, disrupters no longer can be expelled from school. Instead, as a matter of what is imagined to be "social justice," disrupters must be allowed to impair everybody else's education.

Has perfect safety somehow been restored to schools by the Black Lives Matter movement and the vandalism of statues of Columbus and other historical figures? Of course not. This clamor against "school resource officers" is just another manifestation of hatred for police -- and, more than that, hatred for any rules of order, which now are presumed to be racist or otherwise oppressive, especially as government officials lose the self-respect necessary to defend order.

As Connecticut should know bitterly, schools are soft targets, threatened not only by their own incorrigible students but also murderous crazies, so having a cop on hand is some protection against external dangers too.

While the state is recovering well from the epidemic, its residents seem to be becoming crazier, apparently from the epidemic's constraints on life. Shootings now are more frequent, even in suburbs, and they're not being committed by the police, though only misconduct by police seems to be of interest to anyone in authority.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

William Morgan: Some big proposals for tiny Central Falls

There seem to be four facts about Rhode Island's smallest city that most people know: smallness, density, ethnic mix, and that Viola Davis grew up here.

With 20,000 people squeezed into 1.29 square miles – seven times larger than Vatican City and almost as big as the principality of Monaco – Central Falls is one of the densest municipalities in the country.

Broad Street, Central Falls, 1908.

Central Falls is also one of the most diverse communities anywhere, which is saying a lot for Rhode Island. The Irish came to build the Providence and Worcester Railroad in the mid 19th Century, while Rhode Island's first Francophone church (1875) speaks of the influx of French-Canadians who came to work in the mills. And now the almost-half Latinx population comes from every Spanish-speaking country in the hemisphere.

The Coptic pope may make Cranston his first American stop, and the president of Colombia came to Central Falls on his last visit to the United States. On Roosevelt Boulevard, there is a Salvadoran restaurant next to a Polish club.

As for the first Black actress to win an Academy Award, a Tony and an Emmy, Viola Davis was twice named to Time Magazine's 100 most influential people in the world. But as she told Harper's Bazaar after she got her Oscar, she had a childhood of "abject poverty, living in condemned, rat-infested apartments."

U.S. Cotton Company (also called United States Flax Company), 1863 ff. This was the first factory to be oriented to the railroad instead of the Blackstone River, which first powered the area’s mills.

Central Falls, now a down-at-the heels place, was once an industrial powerhouse, but its cocaine habit gave it the nickname Sparkle City in the 1980s. It simply never recovered from the collapse of the Rhode Island textile industry, in the 1920s. Central Falls's motto, “A City with a Bright Future,’’ seems painfully ironic.

Clearly, a struggling Central Falls, not too long out of receivership, is not East Greenwich, Barrington or Providence's East Side. Yet it deserves better than a reputation of corruption and hopelessness.

Central Falls has a long history. In 1676, during King Philip's War, Narragansett sachem Canonchet massacred a group of Plymouth Colony soldiers there. But mostly it is known as a classic New England mill town along the swift-moving Blackstone River; eight factories were making cloth and thread there by 1825, joining an earlier chocolate factory, laying the foundation for many decades of boom.

Central Falls Woolen Mill, 1870 (left); Pawtucket Hair Cloth Mill 1864 right).

— Photo by William Morgan

Central Falls has some magnificent mills. Recent transformation of some of them into housing is a positive development. When the MBTA's Central Falls/Pawtucket railroad stop reopens, apartments in renovated textile factories ought to be especially appealing to Bostonians looking for cheaper but capacious housing.

Abandoned Central Falls/Pawtucket railroad station, c1911. The proposed new train stop will only have a platform, as there are no plans to restore this magnificent temple of transport.

—Photo by William Morgan

One can imagine tours of Central Falls that would appeal to historians of architecture, engineering, labor relations, immigration and the textile industry. But that alone will hardly turn the city's fortunes around.

How about some immodest proposals to make all of Central Falls a national laboratory for the study of architecture and urban design, and much more?

On a Blackstone River bridge built by the Works Progress Administration

— Photo by William Morgan

This New Deal-like project could attract national corporations, foundations and think tanks, but let's begin with Rhode Island colleges and universities. (Ideally, the state should be involved, but it is doubtful that it has the resources or the inclination to invest much more in Central Falls.)

Possible avenues of support and study might include:

- Brown to study and teach languages and government.

- RISD, perhaps in concert with MIT and Harvard, to work on planning and design issues.

- The education school at Rhode Island College to work on improving the schools, joining the nationally recognized Learning Community already in place.

- URI engineering to explore how to revive the mills – to manufacture goods, attract technology and provide employment.

- Johnson and Wales to expand upon and encourage the diverse ethnic cuisines (and perhaps revive the chocolate factory). Their hospitality program could create B and B's with a genuine triple-decker experience.

And consider tiny Monaco, with its grand prix races. So how about a road race–maybe vintage cars overseen by New England Tech–along the Blackstone from Roosevelt Boulevard to Valley Falls Pond.

Given its density and smallness, Central Falls could become a model cooperative experiment, showing the region and the nation how to create an urban renaissance in a post-pandemic world.

A factory that speaks of Central Falls’s legacy of industrial prowess

—Photo by William Morgan

Providence-based architectural writer William Morgan has a degree in the restoration and preservation of historic architecture from Columbia University. He’s the author of many books.

Llewellyn King: COVID-19 has jump-started a revolution in how and where we live, work, shop

Many malls will empty out.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Dimly through the fog of the future some structures are emerging.

Some of the purely physical are becoming discernible. The changes in work, collective consciousness and play are harder to bring into focus.

We -- call us a ravaged generation -- will face a future, the future indicative, radically different from that past which we have known.

The obvious is that work is changed, rearranged and at times lost. A lot of real estate will be begging for a mission or will have to face the wrecker’s ball. Shopping centers will see huge change, maybe devastation.

Those big-box stores that anchored shopping centers will be fewer. Some might be converted to gyms or old-fashioned markets with dozens of small stalls. But these uses are limited, and those cinder-block behemoths are many.

Some have suggested that big-box stores can be converted to affordable housing. But architects say it is easier to knock them down and build new homes on their sites. Like the bomb craters that dotted London after World War II, these will be a kind of ruin for some time, a reminder as to how life was.

After the shopping centers, come the office buildings -- the very symbol of a modern city, from the grand Empire State Building, in New York, to the flashy, mostly glass Shard skyscraper, in London, to the wildly imaginative buildings that were built as symbols around the world as much as needed work space. Now they’ll be sentinels of the city of the past.

The short story is that fewer people will be going back to work in offices. Telecommuting has rapidly come of age; it is acceptable and even desirable. Many, like myself, won’t like it.

Human contact has been part of work since urbanization began. Indications are that we’re going to be less urbanized, more suburbanized and ruralized.

People who have commuted vast distances into cities -- like those who left home at 4 a.m. in Connecticut to be at their desks in Manhattan at 8 a.m. -- will sleep in without guilt.

It isn’t just that COVID-19 has forced us to work differently, at home and separated, it’s that digitization has matured enough to make it possible, almost in confluence with the demands of life under the virus. Magically, Zoom has changed just about everything. It’s been not only a liberating force, but also a force for change.

But huge change and the innovation that will accompany it will have a price.

One survey found that 53 percent of the nation’s restaurants will never reopen, and a lot of wonderful people will be out of work -- for a long time. Restaurateurs are the most entrepreneurial of people, and many will open new venues. But that takes time and capital.

This loss of traditional work, which applies across the hospitality industry, will have deleterious impacts elsewhere. For example, the fishing industry can’t sell all its catch. It has always heavily depended on restaurants.

COVID-19 isn’t alone in reshaping the future. For years digitization and artificial intelligence, which have made telecommuting possible, have been subtracting jobs.

Farming, for example, is undergoing relentless change. Today’s farmer is more a systems manager than the renaissance figure of the past who could help a cow give birth, repair a tractor, taste soil to determine its pH, and handle the harvest with migrant help. Now tractors and farm equipment are fully digitized and can operate from a laptop on a kitchen table, and the harvest is increasingly automated by sensitive robots with multiple sensors guiding kind claws.

It's a new world and we need to be brave and imaginative to master it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

See:

whchronicle.com

A very moving show

Part of “WOW: Wind on Water,’’ a free public art exhibit along Boston Harbor in the city’s Charlestown section. It features 31 of artist Lyman Whitaker's metal Wind Sculptures. With usually plenty of wind along the Boston waterfront, you can be pretty sure these works will usually be moving.

See:

https://www.whitakerstudio.com/

The show is hosted by the Navy Yard Garden Association in partnership with the Boston Planning & Development Agency and also made possible by a grant from the Boston Mayor's Office of Arts and Culture.