And which parts of the 'inerrant' Bible to teach with taxpayer money?

A Gutenberg Bible, the first printed Bible (mid-15th Century). It’s written in Latin Vulgate.

— Photo by NYC Wanderer (Kevin Eng)

Silver and Elm streets in Waterville, Maine, in 1910, showing the Universalist Church, which was established in 1832. Colby College — and its superb art museum — is in Waterville. Note the beautiful elm trees.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The U.S. Supreme Court, run by right-wing extremists called, very inaccurately, “conservatives,” continues to erode walls between religious organizations (real or purported) and government, ruling, for example, last week in the case of two “born again’’ Christian schools in Maine that they can’t be excluded from a state tuition program. Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the 6-3 majority, says that states that subsidize private schools can’t discriminate against religious ones. But a couple of tricky things here are that some religious schools operate as theological propagandists to the public and as adjuncts of the Trump/QAnon Republican Party.

Consider:

One of the two schools, Temple Academy, in Waterville, says it expects its teachers “to integrate biblical principles with their teaching in every subject” (including science) and teaches students “to spread the word of Christianity.” It seeks:

“To foster within each student an attitude of love and reverence for the Bible as the infallible, inerrant, and authoritative Word of God.’’

But which translation/version of the Bible to use? Which one is “infallible”?

What about the Good Book’s innumerable contradictions? And its support in places for slavery and violence? Only God knows!

The other institution, Bangor Christian Schools, says it wants to develop “within each student a Christian worldview and Christian philosophy of life” – whatever that means in these days of public hyper-hypocrisy.

And both institutions’ admissions policies let them deny enrollment to students based on actual gender, gender self-identity, sexual orientation and religion, and require their teachers to be born-again Christians. (I admit, by the way, that I’m weary of “sexual-identity’’ issues.)

Fine.

It’s their business, until the matter of taxpayer money beclouds the situation.

Evangelicals are a key part of the coalition that has ardently supported the least Christian and most immoral president in American history, but Trump promised he’d get them the sort of judges they wanted and he came through. (And then he got them to send him millions of dollars, which he pocketed.)

This reminds me of the fact that too many organizations (including those run by TV con men preachers) claiming to be mainly “religious” in order to be tax-exempt are in fact political-propaganda or commercial organizations that under tax laws are not supposed to be tax-exempt. A lot of us are becoming increasingly irritated by having to pay their taxes for them.

For some reason, this reminds me of a school reunion I attended back in 2016 in which I was asked to preside over a memorial service for our departed schoolmates. After the school chaplain gave me the program printout, I noticed that it was a Christian service – Lord’s Prayer, Corinthians, etc. – and asked the minister (an Episcopalian): “What about the Jewish classmates?’’ of which there were a few. “They can suck it up,’’ he replied with a smile.

The service took place without incident.

Paul Bunyan statue in Bangor. Maine has an old and famous lumber industry because of its vast forests.

— Photo by Dennis Jarvis

Don Pesci: ‘Common sense’ and Connecticut’s gun laws

AR-15-style guns

VERNON, Conn.

Perhaps someone in Connecticut’s General Assembly should propose a law forbidding legislators and state officials from misusing the expression “common sense” and its derivatives.

“The nation’s highest court,” a Hartford paper reported in late June, “overturned a New York law that dates back to 1913 and says that applicants need to show ‘proper cause’ that they need a gun for self-defense in order to obtain a license that they could carry the concealed weapon in public.

“But the court ruled 6-3 that the New York law ‘violates the Fourteenth Amendment by preventing law-abiding citizens with ordinary self-defense needs from exercising their right to keep and bear arms in public.’”

The ruling produced a spate of objections from Connecticut politicians in which the expression “common sense” and its derivatives were painfully iterated by so called “gun control advocates.”

William Tong, Connecticut’s attorney general, advised that Connecticut gun-restriction laws, different than those of New York, are not “immediately impacted” by the high court’s ruling. However, Tong nevertheless characterized the ruling itself as “a radical rewrite of the court’s prior positions on the Second Amendment and states’ rights to pass common sense gun-safety legislation.”

Tong left it to others to explain how a ruling that supported the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution could possibly violate common sense. And Connecticut “fact checkers” were unmoved by Tong’s notion that the court’s most recent decision was a “radical rewrite” of the High Court’s previous Second Amendment decisions.

In effect, the ruling says, in blunt language, that state licensing laws cannot be permitted to trump Second Amendment rights, a decision most commonsensical lawmakers would regard as commonsensical.

After quelling the notion that the high court’s decision might put in jeopardy Connecticut’s gun-restriction laws, Tong went on to characterize the court decision as “reckless.” The consequences “for public safety nationwide are dire,” he said, but not so dire as to dethrone Connecticut’s own gun-restriction laws. Facing such absurdities, common sense immediately took flight.

U.S. Sen. Dick Blumenthal, the Connecticut Democrat, suffering for years from a nagging bout of hoplophobia, an irrational fear of guns, characterized the Supremes’ decision as a spur to gun violence: “This deeply destructive decision will unleash even more gun violence on American communities,” Blumenthal said. “It will only put more guns in public spaces and open the floodgates to invalidate sensible gun-safety laws in more states. Worse yet, it is a significant step backwards at a moment when horrendous shootings happen across our country every day, taking too many beautiful lives and terrorizing generations of Americans.”

And, in keeping with a Democratic Party campaign theme, the court’s ruling, Blumenthal added, fails to uphold “common sense safeguards to reduce gun violence.” However, “This opinion in no way impugns the constitutionality of the common sense Bipartisan Safer Communities Act that the Senate should approve this week. As gun violence soars, Congress must heed the will of the majority of Americans who support gun-safety measures and break the legislative logjam to stop this senseless violence. This activist Supreme Court is once again legislating from the bench, but Congress must continue to legislate for a safer America.”

By upholding the clear language of the Second Amendment, the court is “activist,” and “legislating from the bench.” However, the court’s “activist” decision in no way “impugns the constitutionality of the common sense Bipartisan Safer Communities Act that the Senate should approve this week,” a bill fashioned by a refreshingly bipartisan Congress and Blumenthal and Chris Murphy, the other Connecticut senator, just in time for the 2022 elections.

Are Blumenthal, Murphy and Tong prepared to cease and desist attaching invidious labels to a court that upholds uncommonly sensible Bill of Rights amendments?

Neither Tong nor Blumenthal nor Murphy have yet argued that the court’s recent decision subverts the Bill of Rights.

Surely none of these supposed constitutional scholars believe that licensure, often overused to subvert commonsensical processes, should take precedence over constitutional provisions such as the Second Amendment – “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed” or the Fourteenth Amendment -- “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws” ?

Neither Blumenthal nor Murphy has been asked why their compromise legislation could not have passed bipartisan muster if offered immediately following Connecticut’s Sandy Hook massacre. Nor have they been asked to explain why murders involving guns in the nation’s urban areas have not been halted – say, in Chicago and Hartford, Connecticut’s capital – by highly restrictive gun laws.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

If not always welcoming

“Wide Ocean” (painting), by Newburyport, Mass.-based artist Jennifer Day, at Miller White Fine Arts, Dennis, Mass.

‘Not a distraction’

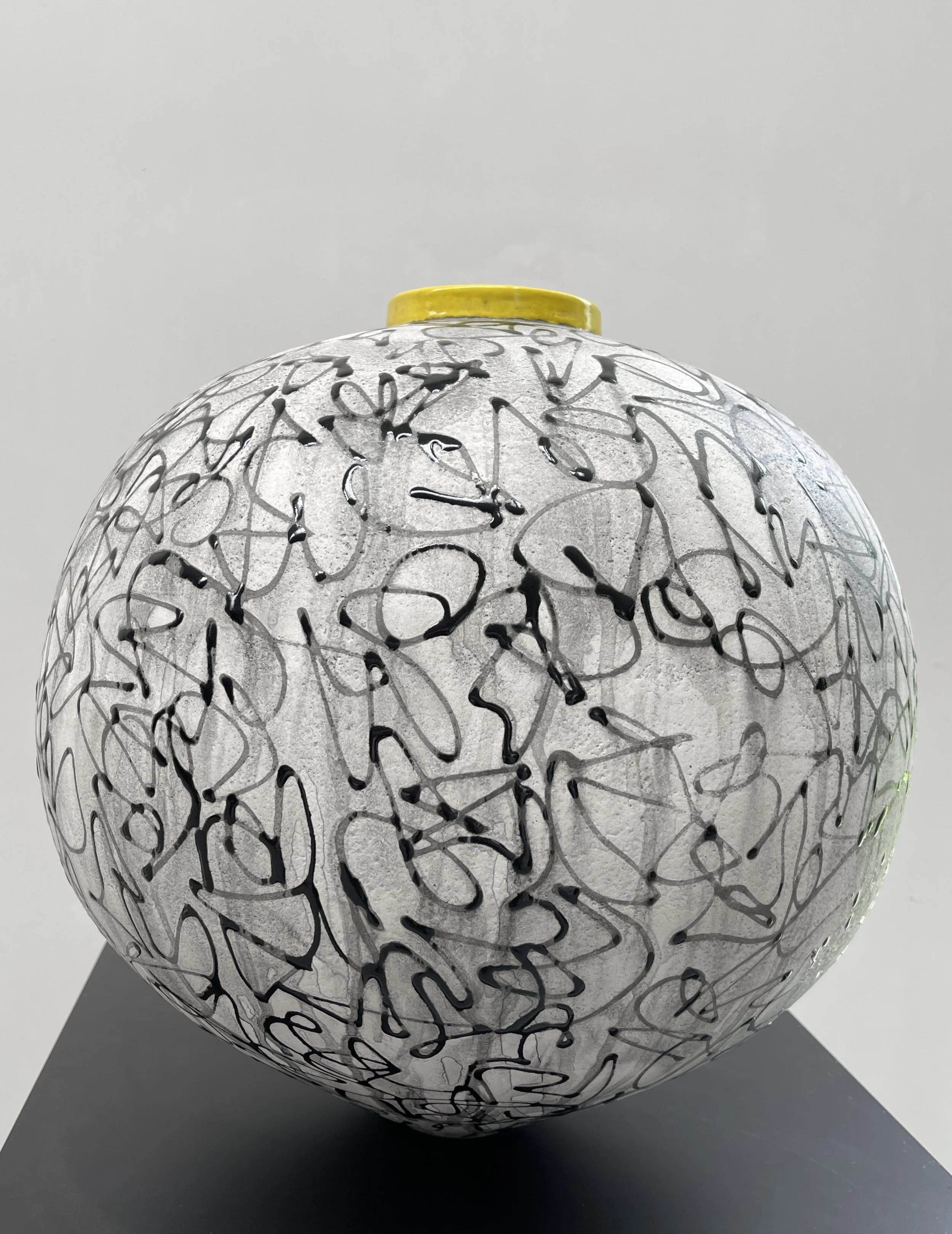

“Untitled,’’ by Boyan Moskov, a native of Bulgaria who now lives in New Hampshirel in the 13-artist show “Ceramics — New Work,’’ at Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine, July 9-Aug. 6.

He says: “When I create work, I don’t want it to interfere with its surroundings. My objects are simple and elegant with clean lines. At the same time, they stand bold and strong. A beautiful accent, not a distraction.’’

Ogunquit River in Wells

— Photo by MoVaughn123

Todd J. Leach: Clearing up some confusions about student debt

Congreve Hall at the University of New Hampshire’s flagship campus, in Durham.

— Photo by Kylejtod

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

The student-debt narrative seems to be increasingly dominated by sensational anecdotes. I recently watched a segment on a national morning television show in which a student with $290,000 in student debt was being held up as an example of how big the problem is.

The story suggests that the cost of tuition for a four-year degree, one from a public institution in this case, is nearly $300,000. Only it isn’t, at least not for the institution that the example above was based on. In fact, the average cost of attendance at the institution used in this particular story was only $28,000 a year, according to the federal College Scorecard. One might still argue that $28,000 a year is too high an average cost for tuition, but that also includes room and board. A high-need student could receive up to $6,895 a year in Pell Grants and probably qualify for even more institutional student aid funding. In other words, a high-need student would likely be paying less than $22,000 a year.

This is not to say that there are no institutions that have a cost of attendance that could exceed $290,000, But for high-need students choosing to attend a public institution, or a low-cost pathway at a private institution, and who are eligible for full Pell Grants and institutional aid, it is still possible to find a path that is much less expensive. Some states, such as New Hampshire, offer gap programs that ensure high-need students can attend tuition free. While room and board is separate from tuition, students that are able to commute can further contain the cost of education.

So how is it a student might have two or three times in debt what it actually costs to attend four years of college?

To start with, there are many different loan types that might be lumped under the heading of student debt. As far as federal Direct Loans go, there are subsidized and unsubsidized loans. Direct subsidized loans require a student to demonstrate financial need. High-need students who are still considered “dependents” may borrow up to $23,000 in aggregate of subsidized loans (total across the four years).

In addition, those same dependent students may borrow an additional $8,000 in Direct unsubsidized loans. Independent high-need students can borrow up to $23,000 in subsidized Direct loans and an additional $34,500 in unsubsidized Direct loans. If you are keeping track of the math, it means that a dependent student may borrow up to $31,000 in Direct federal student loans and an independent student may borrow up to $57,500. Those number still do not add up to the $290,000 example showcased in the story referenced in this example.

What else could be in that $290,000 number? Several things, and almost anything. There are plenty of private loan options available that are not need-based and that have few if any restrictions on how that money can be used. In fact, not all debt incurred by students is for education purposes. Students may borrow money for vacations, cars, entertainment or to support a spouse and dependents while they are unable to work during their educational pursuits. When the numbers are self-reported, they might also include money borrowed from friends or family, as well as money the student has racked-up on their credit cards. The reality is that average Direct federal student debt is under $30,000, according to the Federal Reserve.

There have been numerous calls and proposals for debt relief, but to assess the merits of those varied proposals it is first important to understand the various forms of debt and know exactly what debt is being forgiven. It is also important to understand that debt relief would affect individual college graduates very differently.

For example, a student with no financial need who borrows $25,000 in order to fund summer travel experiences will not be affected the same way as a high-need student who minimized their debt by commuting and borrowing only $5,000.

An even greater equity issue may exist when it comes to students who avoided debt altogether. This is not to say that loan-forgiveness programs have no virtue. Like any investment, student-debt forgiveness should not only have a price tag attached to it, but also some specified goals. Some states have used loan forgiveness as a way to attract graduates to a particular region, while other programs are aimed at incentivizing students to choose particular career paths. In either of these cases, the type of loan does not matter since the objective is incentivizing choices, but if the objective is to address economic disparity or poverty in general, then the details, such as the current earning level of those receiving debt forgiveness, matters.

According to the Federal Reserve, the total amount of outstanding student debt is well above a trillion dollars, which raises one final question when assessing forgiveness options: What are the opportunity costs? Even forgiving all $1.5 trillion of outstanding debt will not lower the cost to attend college, improve access or build a stronger pipeline of graduates for the workforce the way an increase in Pell Grants would. Unfortunately, this may be a false choice. These are policy questions, and the reality may be that it is more feasible to gain support for some form of debt forgiveness than to increase direct subsidies such as Pell Grants.

Regardless of the ultimate decisions on debt forgiveness, we should be looking at ways to minimize student debt to begin with. The cost of attending a four-year institution is certainly one major factor and there are several ways that cost could be further reduced, such as: increasing Pell Grant awards; developing more low-cost delivery options (including online, community college transfer pathways and early college options); and, of course, encouraging institutions to continuously work to find efficiencies. Debt could also be reduced by increased screening and accountability for institutions that target vulnerable students with deceptive practices, as we have seen with some for-profit institutions. The federal government has already forgiven billions of dollars in student-loan debt associated with deceptive for-profits, including $5.8 billion that resulted from the failure of Corinthian Colleges. Beyond college costs and accountability, there are other measures that could be considered and that includes greater accountability for loan providers.

There are steps institutions in general can take to ensure careful borrowing decisions on the part of students. For example, a common practice today is to actually package student loans for accepted students and put the onus on the student to turn it down rather than simply informing the student what they are eligible for should they want to take out loans. Perhaps one of the most effective tools for reducing debt is better information. While not a perfect tool, the federal College Scorecard provides information on cost of attendance and on average earnings of graduates, but I suspect very few families and students are making the Scorecard a significant part of their decision process.

Perhaps it is time to expect institutions to more prominently make data, such as their student-loan default rates, available to prospective students. Students should not just be informed how much they can borrow but what are the chances they will be able to pay it back.

Ultimately, the bigger issue may not be the amount of student debt but that graduates are struggling to pay it back. While the focus is currently on whether or not students should be liable for the totality of their student-loan debt, institutions should anticipate greater focus on their student loan default rates and the return on investment for their graduates. Once again, not all student debt is the same.

Todd J. Leach is chancellor emeritus of the University System of New Hampshire and former chair of NEBHE.

‘Lost truly at last’

A section of Vermont’s Long Trail, which from the Massachusetts line to Quebec.

“I think I sought it. I think I

could not know myself un-

til I did not know where I was.

Then my self-knowledge con-

tinued for a while while I found

my way again in fear

and reluctance, lost truly at

last….’’

— From “Lost” (in the woods), by Hayden Carruth, an American poet and teacher who lived many years in the town of Johnson, in northern Vermont.

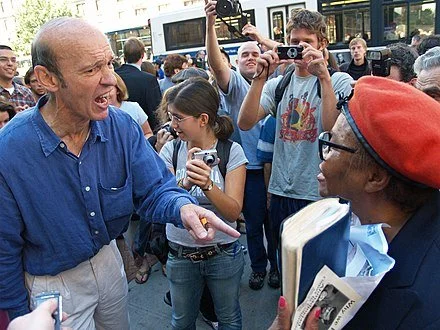

Cold or angry even in summer

— Photo by David Shankbone

South Boston

''This can be a cold place, Boston, and the weather is the least of it. We're often unwelcoming to outsiders. We have a maddening trait of sniping at insiders. We have equal parts determination and aloofness proudly bred into our native bones like the hunting instincts in championship dog.''

--Brian McGrory, in The Boston Globe of March 15, 2002

When he just trying to have fun

“They Thought He Was Dangerous” (mixed media on canvas), by Massachusetts artist and teacher Chandra Mendez-Ortiz, in the group show “The Long View: What Do You See (Do You See Me!),’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, June 29-July 31. The gallery says the show explores “a space where one reflects but imagines forward.’’

Trapped in a cycle

Tideline in Truro, Mass., on outer Cape Cod, where poet Alan Dugan lived.

Photo by Hqfrancis

“Water runs up the beach,

then wheels and slides

back down, leaving a ridge

Of sea-foam, weed, and shells….

One thinks: I must

break out of this

cycle of life and death….’’

-- From “The Sea Grinds Things Up,’’ by Alan Dugan (1923-2003)

Early evening at Head of the Meadow beach, North Truro

— Photo by Seduisant

The Truro Vineyards, in North Truro.

— Photo by Caliga10

David Warsh: The far right's successful fifty-year campaign to pack the Supreme Court

Better when empty? The interior of the U.S. Supreme Court.

— Photo Phil Roeder

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was the summer of 2005. George W. Bush had been re-elected president the autumn before. He possessed political capital, he exulted, and intended to use it. His inaugural address implicitly defended his invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and, without mentioning his embrace of NATO expansion, went further still: “[I]t is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.”

A popular uprising in Lebanon soon boiled over, was dubbed “the Cedar Revolution,” Syria agreed to end its thirty-year occupation of southern portion of the country, and Newsweek asked, on its cover, “Was Bush Right?”

But the war in Iraq remained bogged down. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice seemed to replace Vice President Dick Cheney as Bush’s closest foreign-policy adviser. The president’s major domestic initiative, a plan to privatize the Social Security System, on which Bush had campaigned since 1978, was abandoned. And in August, Hurricane Katrina flooded and flattened New Orleans.

Bush focused on the Supreme Court.

Sandra Day O’Connor announced her retirement a few months before. Eager to nominate the nation’s first Hispanic Supreme Court justice, Bush’s first choice was his friend and former White House counsel, Atty. Gen. Alberto Gonzales. Objections to his candidacy were raised, from anti-abortion conservatives in particular. So in July Bush nominated federal Appeals Court Judge John Roberts instead.

Within weeks, Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, after a lengthy battle with throat cancer. Bush re-nominated Roberts, this time to replace the chief, and to succeed O’Connor, he nominated another old friend, Harriet Miers, a corporate lawyer from Dallas, who had replaced Gonzalez as White House counsel. She was widely criticized for lack of judicial experience.

So, despite his determination to nominate a woman, Bush chose Samuel Alito instead.

In the 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama defeated John McCain. The next April, David Souter announced his retirement from the high court and Obama nominated federal Appeals Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor to succeed him. She was confirmed in August. Associate Justice John Paul Stevens retired the year after that, and though Obama was offered bipartisan support for the candidacy of federal prosecutor Merrick Garland, he nominated former Solicitor General Elena Kagan instead.

After Associate Justice Antonin Scalia died unexpectedly, in February 2016, Obama finally sent Garland’s name to the Senate to succeed Scalia, but even with seven months remaining before the November election, it was too late. Senate Majority Leader Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) refused to act on the nomination, and when Donald Trump was elected, it expired. During his term, Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett to replace Scalia, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Anthony Kennedy. McConnell got all three confirmed by the Senate.

It is not easy to pack the Supreme Court, but, working diligently, over a period of fifty years, a coalition of conservative lawyers, evangelical Christians and Catholic activists, had finally succeeded.

I was reminded of all this when I took down from the shelf The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: the Battle for the Control of the Law (Princeton, 2008), by Steven Teles, of Johns Hopkins University. Of particular salience was the early chapter on “The Rise of the Liberal Legal Network,” in which Teles describes as the conjunction of the Supreme Court led by Earl Warren and the development of an extensive supportive structure in law schools during the Rights Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s.

After that, this splendid book describes nearly everything you need to understand about the counter-mobilization that developed in the 1970s and 1980s: the advent of conservative public interest law in the early 1970s (and the early mistakes from which its institutions learned); the origins of the law and economics movement and its institutionalization by Henry Manne; the counter-networking since 1982 of the Federalist Society. There is a lot of history to imbibe in order to understand how the movement .achieved its most cherished goal last week.

On the other hand, if you want a glimpse of where the intermingling of law and economics is headed, read Republic of Beliefs: A New Approach to Law and Economics (Princeton, 2018), by Kaushik Basu, of Cornell University. Basu is a development economist, former chief economist of the World Bank (as were Paul Romer, Joseph Stiglitz and Anne Krueger), and, like them, a theorist; in his case, a student and collaborator of Amartya Sen and Anthony Atkinson. Basu expects focal points, a concept derived from game theory to play a central role in rethinking the relationship between economics and law. (Better, perhaps, to call it the study of interactive decision-making.)

What’s a focal point? You know one when you see one: shared manifestations of a psychological capacity, prevalent among humans, especially those who share common cultural backgrounds, which enables individuals to guess what others are likely to do, when faced with the problem of choosing from one among several possible options. A classic example? The decision whether to drive on the left or the right side of the road.

But that’s story for another day; a project for the next fifty years.

Meanwhile, if you are simply looking for the damaged but still-healthy roots of the mainstream Republican Party, the place to start is with Chief Justice Roberts’s opinion in the cases last week, in which he dissented from the “relentless freedom from doubt” displayed by his colleagues in their majority decisions last week:

The Court’s decision to overrule Roe and Casey {abortion cases} is a serious jolt to the legal system – regardless of how you view those cases. A narrower decision rejecting the misguided viability line would be markedly less unsettling, and nothing more is needed to decide this case.

George W. Bush’s original two preferences for the high court– Gonzales and Miers – surely would have concurred, had they been nominated and confirmed as associate justices. Roberts, it seems to me, had become the de facto leader of the old version of the Republican Party, U.S. Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyoming) its floor leader in Congress. If you want to know what will happen next, bide your time until autumn and carefully sift through the mid-term election results. Then fasten your seat belts for 2024.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Tangled up in empathy

“Three Models Legs and Hands” (watercolor,), by Donald C. Kelley, courtesy of The Artists Group of Charlestown (part of Boston). This is in the show “Donald C. Kelley: The Legacy Continues,’’ sponsored by The Artists Group of Charlestown, at the StoveFactory Gallery, Charlestown, through July 17.

Kelley (1928-2018) wrote in his artist statement: "Empathy lies at the heart of my figure drawings; I try to communicate directly through feeling ... when I am drawing or painting a representation of the body, I imagine myself within that body."

Site of Puritan leader/Boston founder John Winthrop's "Great House" in City Square, Charlestown, uncovered during the Big Dig. Archeologists said the building was occupied by Winthrop from July to October 1630. It was the Massachusetts Bay Colony's first government building, as well as Winthrop's dwelling before he moved to Boston.

Shoreline friend

“Favorite Dock #4, by Wendy Prellwitz, in her joint show with Sue Charles, “Down to Earth and Out to Sea,’’ at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

Philip K. Howard: Our governing processes have become paralytic, and what to do about it.

The Bayonne Bridge, where an urgently needed improvement has been blocked by inane regulatory red tape.

Crook Point Bascule Bridge (1908), once connecting Providence and East Providence, R.I. It’s been stuck in upright position since 1976.

— Photo by Matthew Ward

Governing is not a process of perfection. Like other human activities, governing involves tradeoffs and trial and error. One of the most important tradeoffs involves timing. Delay in governing often means failure. Nowhere is this more true than with environmental reviews for infrastructure. Every year of delay for new power lines, modernized ports, congestion pricing for city traffic and road bottlenecks means more pollution and inefficiency.

New York Times columnist Ezra Klein has awakened liberal readers to the reality, hiding in plain sight, that governing processes are paralytic: “The problem isn’t government. It’s our government. … It has been made inefficient.”

The other week columnist George Will asked whether America “can do big things again.” Citing our work, and the absurd 20,000-page review for raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge, which connects Bayonne, N.J., with New York City’s Staten Island, to permit new post-panamax ships into Newark Harbor, Will calls out “the progressive aspiration to reduce government to the mechanical implementation of an ever-thickening web of regulations that leaves no room...for judgment.” American Enterprise Institute scholar and Washington Examiner columnist Michael Barone, also citing our work, the other day called for a rebooting of government to “sweep out the ossified cobwebs.”

The recent $1.2 trillion federal infrastructure law contains tools to streamline permitting, including presumptive 200-page limits on environmental reviews and two-year processes that we championed. But actually giving permits requires officials to use their judgment about priorities and tradeoffs, not to overturn every pebble. That may be a problem in current bureaucratic culture. In a letter to the editor of The Washington Post, an environmental official objects to my suggestion that raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge using existing foundations “involved no serious environmental impact.” He asserts that “bringing larger, more polluting ships and increased cargo” to the port “would result in increased diesel pollution from both the ships and the trucks transporting the cargo.”

Actually, the new larger ships are much cleaner, pollution-wise and burn much less diesel fuel per container. That’s a reason they’re more efficient. Increasing the capacity of the Newark port will indeed result in more truck traffic, but those containers have to come in somewhere.

You start to see the problem. It’s impossible to talk about environmental impact in the abstract. What’s needed is a governing culture that can make judgments about practical tradeoffs.

In a piece for Fortune on efforts to protect kids online, Jonathan Haidt and Beeban Kidron cite my work on the benefits of a principles-based approach to writing laws.

Julia Steiny in the Providence Journal cites my work in describing how Providence public schools are being crushed by law: “The system suffers from what author Philip Howard calls The Rule of Nobody. He says that the law operates ‘not as a framework that enhances free choice but as an instruction manual that replaces free choice.’”

For the American Spectator, E. Donald Elliott provides a history of Common Good’s effort to bring about infrastructure permitting reform.

Philip. K. Howard is a New York-based lawyer, civic and cultural leader, author and photographer. He’s chairman of the legal- and regulatory-reform organization Common Good (commongood.org) and the author of, among other books, The Death of Common Sense and The Rule of Nobody.

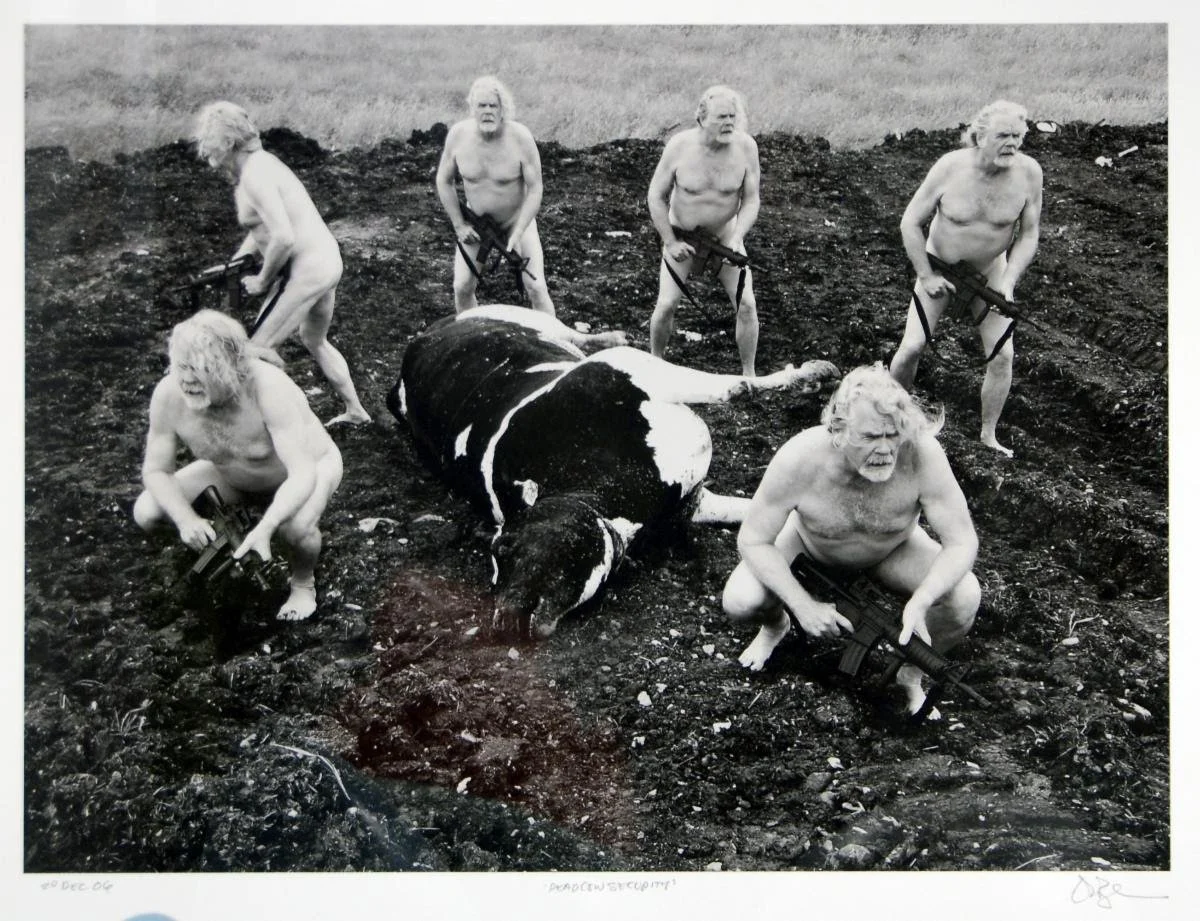

Protecting the pasture

“Cow Security: Homeland Security Series’’ (digital photographic composite), by John Douglas, in the show “John Douglas: A Life Well Lived,’’ at the Gallery@The Karma Bird House, connected with the Northern New England Museum of Art, Burlington, Vt., through Aug 22. (Photo courtesy of Eleanor “Bobbie” Lanahan).

The museum says:

“John Douglas’s memorial retrospective documents his long, productive, and substantive body of work. Douglas called himself a ‘truth activist.’ His irreverent, activist beliefs, and Zen-like appreciation of the world fueled his decades of creative output. Douglas unceasingly addressed injustice, hypocrisy, unjust wars, and climate change. In ‘Homeland Security' he leverages American symbols and uses himself as a central actor with near complete humility to create a forceful critique of our cultural priorities.’’

ECHO, Leahy Center for Lake Champlain, formerly the Lake Champlain Basin Science Center, is an science and nature museum on the Burlington waterfront of Lake Champlain. It hosts more than 70 species of fish, amphibians, reptiles and invertebrates, major traveling exhibitions and the Northfield Savings Bank 3D Theater. It’s named for U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy, of Vermont, who has long promoted the protection of the Lake Champlain Basin.

‘Our naked frailty’

“In June, amid the golden fields,

I saw a groundhog lying dead.

Dead lay he; my senses shook,

And mind outshot our naked frailty.’’

— From “The Groundhog,’’ by Richard Eberhart (1904-2005), American poet and Dartmouth College professor. He spent most of his post World War II time in New Hampshire and on the Maine Coast.

Earth to earth, sort of

In Mount Auburn Cemetery, near Boston.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“If this is dying then I don’t think much of it.’’

-- Lytton Stratchey (1880-1932), English writer

I enjoy walking through most graveyards, of which New England has many beauties. Wandering around gorgeous garden cemeteries, such as Swan Point, on the East Side of Providence, and Mt. Auburn, on the Watertown-Cambridge, Mass., line, can be soothing, even amidst the memento mori. Actually, giving yourself frequent reminders of death can be healthy: It’s focusing!

But many cemeteries are running out of space because people keep dying – very thoughtless of them. One of the challenges is that many families still want their loved ones’ corpses preserved with chemicals and put into coffins in burial vaults or at least concrete-lined, which take up a lot of room for a very long time. I think that’s related to survivors’ varying levels of denial of death. There’s this (to me) weird idea that somehow preserving that organic, decaying thing called a dead body fends off the person’s annihilation. (I see the decay and disappearance of the body as simply its return to what we all came from – ultimately space dust. Call it recycling.) But I realize, as a former churchgoer, that Christians are told to believe in the resurrection of the body.

Cremation is much better than standard burials, though it requires burning natural gas. Take your loved ones’ ashes home with you in a bag and put them in a vase; they won’t mind. Then in a few or many years, someone will probably forget where that vase is, or even whose ashes are in it.

Then there are the environmentally admirable decisions to compost the remains or use hydrolysis to reduce remains to their elements. A gift to Nature. Yes, this goes against some folks’ feeling that the dead body still contains some supernatural life – a feeling that’s been very profitable for the funeral/burial industry.

Llewellyn King: Prepare for a messy electric revolution

An experimental Firefly electric helicopter, developed by famed Sikorsky Aircraft, based in Stratford, Conn.

In 2016, Solar Impulse 2 was the first solar-powered electric aircraft to complete a circumnavigation of the world.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The 21st Century is set to be The Electric Century. We are in the middle of a profound electrification binge that will leave its mark on every aspect of human endeavor.

I believed this before I attended the Edison Electric Institute annual meeting and convention in Orlando. Now I believe it more than ever. The institute is the trade association of the investor-owned utilities.

Civilization already has been running on electricity, but it will do so in a more complete way in future. In simple terms, what will happen is what hasn’t been electrified will be electrified. Manufacturing, mining, farming and the processing of everything, from grains to making concrete, will be electrified.

The first big shift -- the one we can all see and participate in -- is the electrification of transportation, total electrification. That will include aircraft in time, but light aircraft are already in the experimental phase.

You can see it with the plethora of electric vehicles coming to market from old marques but, more exciting, from new companies making everything from huge tractor-trailer trucks to snazzy new pickups and sedans.

Three of these were among a lineup of all-electric vehicles on display outside the JW Marriott, Grand Lakes, Orlando hotel:

· 2022 Lucid Air: A stunning beautiful sedan, and the MotorTrend Car of the Year, with an impressive range of 530 miles, and an equally impressive price of about $139,000.

· Rivian pickup: One of a range of all-electric pickup trucks; this one designed for lighter loads, but still boasting a towing capacity of 11,000 pounds.

· Freightliner eCascadia: A semi-truck with a load capacity of 82,000 pounds, but a range of only 230 miles.

The significant thing here is the number of new manufacturers. These mean new ideas, new visions, new materials, and new horizons.

Each huge advance in transportation has required new entrepreneurs -- otherwise, the car companies would have built the aircraft. It wasn’t Chrysler, General Motors and Ford that rose into the skies, but new names like Boeing, Douglas and Sikorsky.

Ultimately markets will decide, and markets aren’t welfare organizations. They are cruel judges and executioners as well as supremely generous patrons.

The driver for this revolution is climate change. Twenty years ago, you could still with some credibility debate its reality. Today, the evidence is in every weather forecast. Things are getting hotter and, as any science student will tell you, when stuff heats up, things happen.

The utility industry has embraced the rationale of change to modify and one day reverse climate change through curbing the volume of greenhouse gases going into the air. It starts with their own generation, and soon will embrace all the carbon that spews from boilers and tailpipes.

Revolutions are messy things. Once underway they get a life of their own. There is confusion and mistakes are made at the barricades. But once underway, they can’t be turned back; yesterday can’t be summoned rule tomorrow.

The utilities I spoke to feel they will be able to meet the new electric load demand with a mixture of leveling out the power from intermittent renewables. This is called DSM (demand side management) and uses data from smart-metering to manage the demand in collaboration with their customers. For example, incentivizing commercial firms to agree to shut down some operations during peak demand, and even to enter into agreements with homeowners to operate dishwashers and other appliances late at night.

Then there is using the transport fleet as a big battery. The theory is your new electric vehicle can feed back into the grid as needed when it is fully charged. But there are those who doubt that this will be enough to bridge the gap between generation and future demand. Andres Carvallo, one of the fathers of the smart grid, and a polymath who runs numbers on the future from his perch at Texas State University and his company, CMG Consulting, believes a lot more actual generation will be needed to meet the growth in electrification.

Presumably, much of this would come from the new small modular reactors. Here is a paradox. Utility executives say, to a person, that nuclear is needed, but none say how it will be bought, sited and built. When nuclear is talked up by utilities these days, there is a dream quality about it.

The great goal of the industry, or the revolution if you will, is zero emissions by mid-century. All embrace the electrification surge. Many utilities have plans to eliminate their own emissions, but none is ready for a huge, nationwide surge in demand, nor is there a national plan to deal with pressing impediments like a lack of transmission.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Wiscasset aglow; Castle Tucker

“Tucker Hill View,’’ by Anthony Watkins, in Maine Art Gallery Wiscasset’s “Paint Wiscasset & Plein Air Show’,’ June 29-July 9.

The rather bizarre “Castle Tucker,’’ in Wiscasset. Judge Silas Lee built this Regency-style mansion in 1807 at the peak of Wiscasset's prosperity, when the town was one of New England’s busiest and richest ports, especially for lumber and fishing, as well as a major shipbuilding center. Lee's death, in 1814, combined with the cumulative financial impact of President Jefferson's Embargo of 1807, forced his widow to sell it. The house then passed through several owners hands until 1858, when Captain Richard H. Tucker Jr. , of a Wiscasset shipping family, bought the property. The Tucker family soon updated the interiors and added a new Italianate entrance and then a dramatic two-story porch to what had been the front of the house facing the Sheepscot River.

Looking out from Castle Tucker toward the Sheepscot River.

‘Not particularly pleasant’

Houses on Louisburg Square, on Beacon Hill, Boston

— Photo by Ajay Suresh

“Nothing which is worth while is easy, nor in my experience is the actual doing of it particularly pleasant. The pleasure arises from completion and from the knowledge that one has done the right thing and has stood by one’s convictions.’'

From John P. Marquand’s (1893-1960) The Late George Apley, Marquand’s brilliant satirical novel about upper-crust Boston