Michelle Andrews: In N.H., a painful and confusing colonoscopy medical bill

Lake Sunapee, part of which is in the town of Sunapee, where Elizabeth Melville lives.

‘Elizabeth Melville and her husband are gradually hiking all 48 mountain peaks that top 4,000 feet in New Hampshire.

“I want to do everything I can to stay healthy so that I can be skiing and hiking into my 80s — hopefully even 90s!” said the 59-year-old part-time ski instructor who lives in the vacation town of Sunapee.

So when her primary-care doctor suggested she be screened for colorectal cancer in September, Melville dutifully prepped for her colonoscopy and went to New London Hospital’s outpatient department for the zero-cost procedure.

Typically, screening colonoscopies are scheduled every 10 years starting at age 45. But more frequent screenings are often recommended for people with a history of polyps, since polyps can be a precursor to malignancy. Melville had had a benign polyp removed during a colonoscopy nearly six years earlier.

Melville’s second test was similar to her first one: normal, except for one small polyp that the gastroenterologist snipped out while she was sedated. It too was benign. So she thought she was done with many patients’ least favorite medical obligation for several years.

Then the bill came.

The Patient: Elizabeth Melville, 59, who is covered under a Cigna health plan that her husband gets through his employer. It has a $2,500 individual deductible and 30% coinsurance.

Medical Service: A screening colonoscopy, including removal of a benign polyp.

Service Provider: New London Hospital, a 25-bed facility in New London, N.H. It is part of the Dartmouth Health system, a nonprofit academic medical center and regional network of five hospitals and more than 24 clinics with nearly $3 billion in annual revenue.

Total Bill: $10,329 for the procedure, anesthesiologist and gastroenterologist. Cigna’s negotiated rate was $4,144, and Melville’s share under her insurance was $2,185.

What Gives: The Affordable Care Act made preventive health care such as mammograms and colonoscopies free of charge to patients without cost sharing. But there is wiggle room about when a procedure was done for screening purposes, versus for a diagnosis. And often the doctors and hospitals are the ones who decide when those categories shift and a patient can be charged — but those decisions often are debatable.

Getting screened regularly for colorectal cancer is one of the most effective tools that people have for preventing it. Screening colonoscopies reduce the relative risk of getting colorectal cancer by 52% and the risk of dying from it by 62%, according to a recent analysis of published studies.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, a nonpartisan group of medical experts, recommends regular colorectal cancer screening for average-risk people from ages 45 to 75.

Colonoscopies can be classified as for screening or for diagnosis. How they are classified makes all the difference for patients’ out-of-pocket costs. The former generally incurs no cost to patients under the ACA; the latter can generate bills.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has clarified repeatedly over the years that under the preventive services provisions of the ACA, removal of a polyp during a screening colonoscopy is considered an integral part of the procedure and should not change patients’ cost-sharing obligations.

After all, that’s the whole point of screening — to figure out whether polyps contain cancer, they must be removed and examined by a pathologist.

Many people may face this situation. More than 40% of people over 50 have precancerous polyps in the colon, according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Someone whose cancer risk is above average may face higher bills and not be protected by the law, said Anna Howard, a policy principal at the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network.

Having a family history of colon cancer or a personal history of polyps raises someone’s risk profile, and insurers and providers could impose charges based on that. “Right from the start, [the colonoscopy] could be considered diagnostic,” Howard said.

In addition, getting a screening colonoscopy sooner than the recommended 10-year interval, as Melville did, could open someone up to cost-sharing charges, Howard said.

Coincidentally, Melville’s 61-year-old husband had a screening colonoscopy at the same facility with the same doctor a week after she had her procedure. Despite his family history of colon cancer and a previous colonoscopy just five years earlier because of his elevated risk, her husband wasn’t charged anything for the test. The key difference between the two experiences: Melville’s husband didn’t have a polyp removed.

Resolution: When Melville received notices about owing $2,185, she initially thought that it must be a mistake. She hadn’t owed anything after her first colonoscopy. But when she called, a Cigna representative told her the hospital had changed the billing code for her procedure from screening to diagnostic. A call to the Dartmouth Health billing department confirmed that explanation: She was told she was billed because she’d had a polyp removed — making the procedure no longer preventive.

During a subsequent three-way call that Melville had with representatives from both the health system and Cigna, the Dartmouth Health staffer reiterated that position, Melville said. “[She] was very firm with the decision that once a polyp is found, the whole procedure changes from screening to diagnostic,” she said.

Dartmouth Health declined to discuss Melville’s case with KHN even though she gave her permission for it to do so.

After KHN’s inquiry, Melville was contacted by Joshua Compton, of Conifer Health Solutions, on behalf of Dartmouth Health. Compton said the diagnosis codes had inadvertently been dropped from the system and that Melville’s claim was being reprocessed, Melville said.

Cigna also researched the claim after being contacted by KHN. Justine Sessions, a Cigna spokesperson, provided this statement: “This issue was swiftly resolved as soon as we learned that the provider submitted the claim incorrectly. We have reprocessed the claim and Ms. Melville will not be responsible for any out of pocket costs.”

The Takeaway: Melville didn’t expect to be billed for this procedure. It seemed exactly like her first colonoscopy, nearly six years earlier, when she had not been charged for a polyp removal.

But before getting an elective procedure like a cancer screening, it’s always a good idea to try to suss out any coverage minefields, Howard said. Remind your provider that the government’s interpretation of the ACA requires that colonoscopies be regarded as a screening even if a polyp is removed.

“Contact the insurer prior to the colonoscopy and say, ‘Hey, I just want to understand what the coverage limitations are and what my out-of-pocket costs might be,’” Howard said. Billing from an anesthesiologist — who merely delivers a dose of sedative — can also become an issue in screening colonoscopies. Ask whether the anesthesiologist is in-network.

Be aware that doctors and hospitals are required to give good faith estimates of patients’ expected costs before planned procedures under the No Surprises Act, which took effect this year.

Take the time to read through any paperwork you must sign, and have your antennae up for problems. And, importantly, ask to see documents ahead of time.

Melville said that a health system billing representative told her that among the papers she signed at the hospital on the day of her procedure was one saying that if a polyp was discovered, the procedure would become diagnostic.

Melville no longer has the paperwork, but if Dartmouth Health did have her sign such a document, it would likely be in violation of the Affordable Care Act. However, “there’s very little, if any, direct federal oversight or enforcement” of the law’s preventive services requirements, said Karen Pollitz, a senior fellow at KFF.

In a statement describing New London Hospital’s general practices, spokesperson Timothy Lund said: “Our physicians discuss the possibility of the procedure progressing from a screening colonoscopy to a diagnostic colonoscopy as part of the informed consent process. Patients sign the consent document after listening to these details, understanding the risks, and having all of their questions answered by the physician providing the care.”

To patients like Melville, that doesn’t seem quite fair, though. She said, “I still feel asking anyone who has just prepped for a colonoscopy to process those choices, ask questions, and potentially say ‘no thank you’ to the whole thing is not reasonable.”

Michelle Andrews is a Kaiser Health News reporter. @mandrews110

David Warsh: Of financial revolutions

The Prince of Orange landing at Torbay, England, in the Glorious Revolution that overthrew James II and installed the Prince of Orange, a Dutchman, as William III.

— Painting by Jan Hoynck van Papendrecht

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Many people at least a little about the history of the scientific revolutions of the 16th and 17th centuries; the industrial revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries; and the democratic revolutions of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Very few are familiar with the major details of the financial revolution of the early 18th Century, which began with the reforms of England’s “Glorious revolution” of 1688. In the course of the next sixty years, these developments brought into existence the modern military-industrial complex.

This relative obscurity of these long-ago events is not surprising, for, as best I can tell, the term had no currency before Peter G.M Dickson, in 1967, published The Financial Revolution in England: A Study of the Development of Public Credit, 1688-1756. Until then, the power to spend public money was colloquially described as “the control of the purse.”

It is, however, something of a shame, since what we now call “the national debt” these days is the engine that powers military interventions around the world, from the misadventures of the George W, Bush administrations forays in Afghanistan and Iraq to Vladimir Putin’s quagmire plunge in Ukraine. You can’t fathom those periodic $60 billion appropriations bills without knowing something about the enormous multinational purse that supports NATO.

Instead, our understanding of these matters depends on combinations of vignettes and modern analysis, a sauce that often doesn’t come together.

Among vignettes, an especially appealing recent example is Ways and Means: Lincoln and his Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War, by social historian Roger Lowenstein. It relates how Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, Lincoln’s defeated presidential rival, turned the tide of war against the South on the financial front, “levying taxes and marketing bonds, while desperately batting inflation.” A more encompassing account of government bond markets was related twenty-five years ago and updated in 2010 in Hamilton’s Blessing: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Our National Debt, by John Steele Gordon.

A welcome addition among analytics In Defense of Public Debt, by Barry Eichengreen, Asmaa El-Ganainy, Rui Esteves, and Kris James Michener (2021), a hard-headed survey of debt in the service of the state and what’s known about the limits of borrowing. The wind has largely gone out of the sails of the fad called “modern monetary theory,” thanks to books like this, and the papers cited herein. And the book synthesizes a good deal of valuable history. But the topical treatment of the issues is unlikely to make an impression on the broad public mind. That take a lifetime of research in the manner of Dickson, or, in the case of the cadre of researchers working over insights derived from a famous 1989 article about the origins of modern democracy, by Douglass North and Barry Weingast.

Thus the lack of understanding is of the financial revolution is to some degree the story of a lost book. Dickson died last year, having spent sixty years as a Founding Fellow of St. Catherine’s College, Oxford University. He revised his English Financial Revolution book in 1993, but that second edition is out of print. Even the library copy of the original was missing when I arrived yesterday. You can get some idea of the scope of the problem from its table of contents — and why the story of government bond markets is a hard tale to tell.

The Financial Revolution — 2. The Contemporary Debate — II. Government Long-Term Borrowing — 3. The Earliest Phase of the National Debt 1688-1714 — 4. Problems of Administration and Reform 1693-1719 — 5. The South Sea Bubble (I) — 6. The South Sea Bubble (II) — 7. Financial Relief and Reconstruction 1720-1730 — 8. Financial Relief and Reconstruction 1720-1730 — 9. The National Debt under Walpole – 10. War and Peace 1739-1755 — 11. Public Creditors in England and Abroad– 12. Public Creditors Abroad – 12. Government Short-term Borrowing — 13. Borrowing by Exchequer Tallies — 14. Borrowing by Exchequer Bills — 15. Departmental Credit — 16. The Bonds of the Monied Companies — 17. The Ownership of Short-dated Securities and the Market in Securities — 18. The Turnover of Securities — 19. The Rate of Interest in Theory and Practice — 20. The Origins of the Stock Exchange

A parallel history of events in France adds dimensionality to the story. French Finances, 1770-1795; From Business to Bureaucracy (1970), by John F. Bosher, describes role of the French Revolution in transforming a thoroughly corrupt system of government finance into a less venal and more efficient system. In A Financial History of Western Europe (1993), Charles P. Kindleberger, who assigned the two books in courses he taught in 1979 and 1980, wrote, “Note that the financial revolution of England preceded that of France by a century, and that the view that British military success owed to her financial capacity is matched by the statement that financial incompetence of the French monarchy was the main reason for its ultimate collapse.”

The good news is that not one but two top-flight economic historians are once again working on telling the story of the revolution charted by Dickson fifty years ago. Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution 1688-1720, by Carl Wennerlind, of Barnard College, at Columbia, was under-appreciated when it appeared ten years ago. The author bent over backwards to avoid triumphalism by incorporating, as the financial revolution’s first great success, the story of Britain’s entry into the Atlantic slave trade – the usually glossed-over precipitant and still-less-remembered outcome of the South Sea Bubble.

Anne L. Murphy, of the University of Portsmouth, who spent twelve years working trading interest-rate and foreign-exchange derivatives in the City of London, re-tooled as a historian and published The Origins of English Financial Markets: Investment and Speculation before the South Sea Bubble in 2009. The book won the Economic History Society’s best monograph prize the next year. She is preparing to publish Virtuous Banking: a day in the life of the late eighteenth-century Bank of England.

Meanwhile, Wennerlind’s new book, A Philosopher’s Economist: Hume and the Rise of Capitalism, co-authored with Margaret Schabas, of the University of British Columbia, appears next month. The financial revolution of the eighteenth century is with us every day. The extent and significance of its evolution has yet to be fully spelled out to a 21st Century audience.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Chris Powell: Conn. Democrats' silly obsessions are bringing back ticket balancing

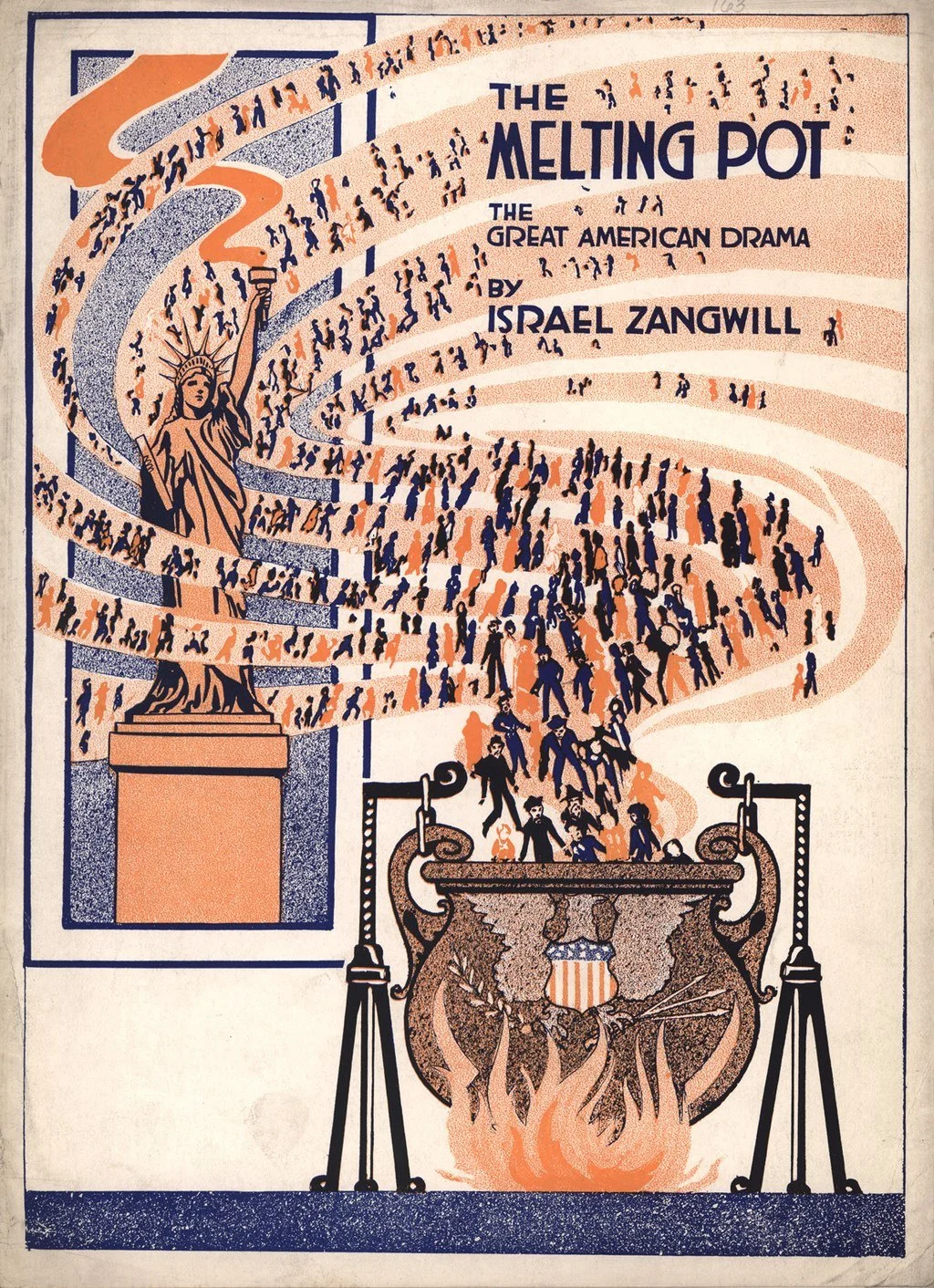

The image of the United States as a melting pot was popularized by the 1908 play The Melting Pot. Has the melting cooled?

MANCHESTER, Conn.

As recently as 50 years ago Connecticut politics still had traces of the old ethnic, racial and religious resentments and rivalries that had arisen through the state's long history, resentments and rivalries that political party state tickets tried to assuage.

Yankee Protestant Republicans scorned immigrant Catholics. While the Irish and Italians both were mostly Catholic, they were also tribal and often found something to dislike about each other, so much so that many Italians became Republicans just because the Irish, having arrived first and been scorned by the Yankee Protestant Republicans, had come to dominate the Democratic Party.

The state's Blacks started leaning Democratic during the New Deal years but race remained the state's biggest prejudice so they didn't get much patronage for their political involvement, and for a long time they were glad just not to be actively oppressed.

Jews were an afterthought in Connecticut politics until Abraham Ribicoff got elected to Congress as a Democrat from the Hartford district in 1948 and came back from defeat for re-election in the Republican landslide of 1952 to run for governor in 1954. Ribicoff ran into what was said to be a whispering campaign targeting him for his religion, so he went on television near Election Day to extol the American dream and his right to aspire to it despite his modest Jewish origins in New Britain. The tactic worked, gaining Ribicoff a small plurality, and it may have been the moment when Connecticut began to grow up a little politically, to start looking past the ethnic, racial and religious prejudices and irrelevancies.

Still, ticket balancing along ethnic, racial and religious lines continued in both parties for a few decades.

For some reason back then both parties tended to reserve their congressman-at-large nominations for a Pole, and when, at the Democratic State Convention in 1962, the Democratic incumbent, Frank Kowalski, stomped out in resentment over being denied a primary for the U.S. Senate nomination, party power broker John M. Bailey, who was both state and national Democratic chairman, urgently sought another candidate with a Polish name.

Bailey found a prospect in the Bristol delegation, a little-known municipal official and war veteran, Bernard F. Grabowski. The legend is that Bailey asked Grabowski three questions:

Are you Polish? Are you Catholic? Can you speak Polish?

When Grabowski answered affirmatively, the Democrats had their nominee and Connecticut its next congressman-at-large.

But amid the national political turmoil of the late 1960s, ticket-balancing was getting in the way of the ambitions of too many state politicians, and after Bailey, the master of machine politics, died, in 1975, there was no one skilled and inclined enough to keep ticket balancing going as ethnicity and race were fading as focal points of life.

Indeed, in the following several decades Connecticut began to think itself somewhat more enlightened for its growing indifference to the ancestry and religion of political candidates and its increasing concern for positions, skills, and character.

But now the state may be regressing, at least to judge by the recent Democratic State Convention, where the party's silly renewed obsession with race and other characteristics irrelevant to the performance of public office targeted nominations for two spots on the state ticket where no incumbents were seeking re-election.

Connecticut Democrats still seem to think that the Connecticut Constitution requires the treasurer's office to be filled by a Black person and the secretary of the state's office by a woman. The party's nominee for secretary this time is not just female but Black as well. Both nominees may do a good job if elected, but they are little known and almost certainly would not have been chosen if they did not provide the racial composition the convention sought.

Of course, few voters may care much about who fills the treasurer and secretary positions, and even with Connecticut Democrats diversity goes only so far. For their ticket's top positions, the ones with the greatest power over policy and patronage -- governor and lieutenant governor -- have gone again to whites, and somehow the ticket apparently lacks a transgender candidate, an oversight that may embarrass the party's most hysterical members.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Don’t stare at it

“Openwork Wedjat Eye” (polychrome faience) (ancient Egyptian, about 1076–655 BCE) at the Worcester Art Museum, opening June 18.

The museum (very impressive for a mid-size city) says:

“The magnificence of ancient Egypt comes to life through jewelry, the most precious and personal of human possessions.’’

Tongue-in-cheek arrogance or the real thing?

Sterling Memorial Library at Yale, in New Haven.

“The Yale president must be a Yale man. Not too far to the right, or too far to the left or a middle-of-the-roader. Ready to give the ultimate word on every subject under the sun from how to handle the Russians to why undergraduates riot in the spring. Profound with a wit that bubbles up and brims over in a cascade of brilliance. You may have guessed who the leading candidate is, but there is a question about him: Is God a Yale man?”

-- Wilmarth S. Lewis (1895-1979), Yale trustee, writer and near-monomaniac collector of the works of Horace Walpole (1717-1787), the British writer. He graduated from Yale in 1918. (He made the remarks above in 1950.)

In 1928 he married Anne Burr Auchincloss, a granddaughter of Oliver B. Jennings, one of the founders of the Standard Oil Company. Mrs. Lewis was also caught up in the Walpole pursuit and devoted her fortune and much time to it until her death, in 1959. Most of their collection was left to Yale.

Irritating and beautiful

New growth and pollen cones of a pitch pine, a common tree on Cape Cod. It’s very flammable.

— Photo by Famartin

“Now I know summer is here, no matter how cold it is at night, for when I went out to the car this morning, the windshield was dusted with orange and the whole shiny dark blue of the body was powdered. The pine pollen has come! This is a thick, almost oily deposit that penetrates everything. If you close a room and lock the windows, the sills will be drifted with the pollen the next morning. The floors turn orange.’’

— Gladys Taber, in My Own Cape Cod (1971)

Moisture maniacs

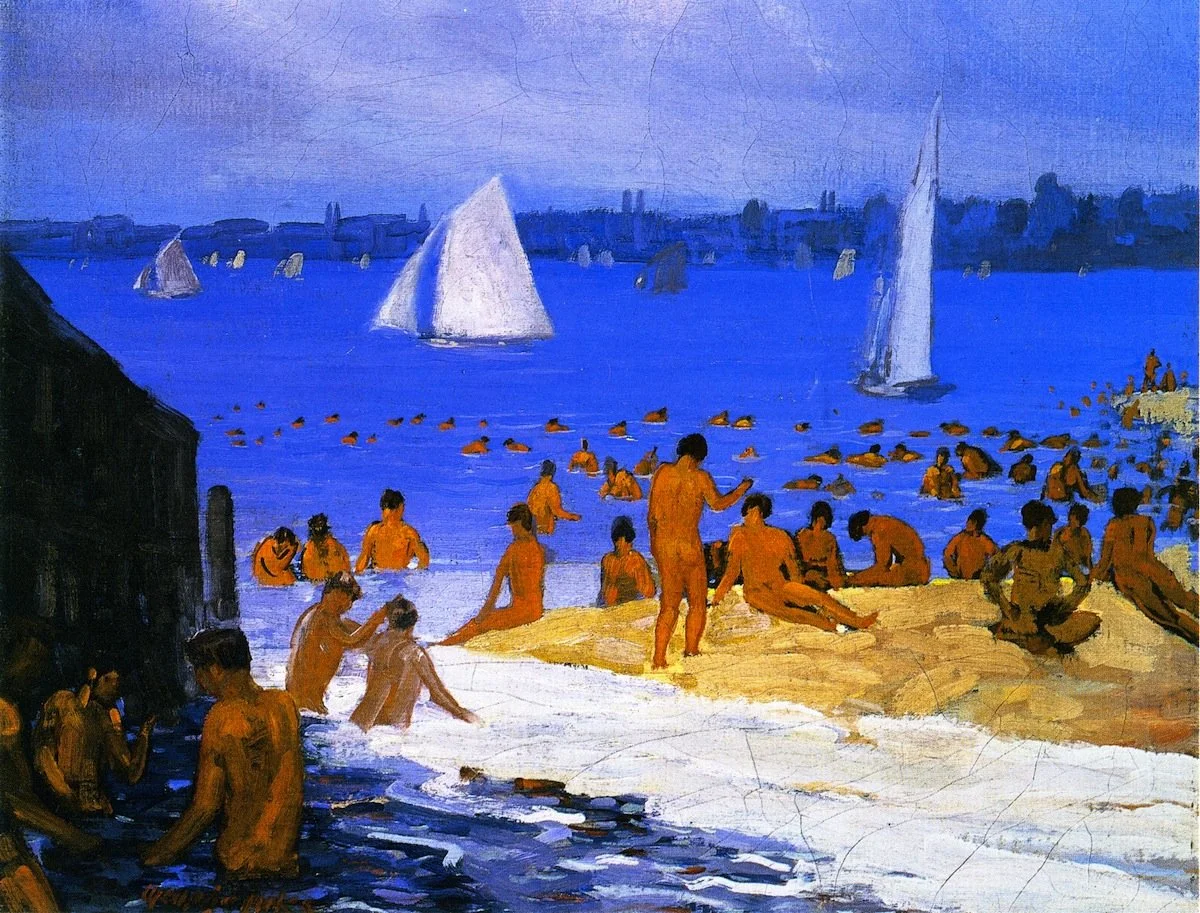

‘‘Adult Swim” (encaustic painting), by Nancy Whitcomb

“L Street Brownies’’ (swimming club in South Boston) (1922), by George Luks (1867-1933). Open-air nudity in 1922?!

Ready for it now

“Give me back the long heat wave, the sweat dripping

from eyelashes, the stained blouses, the black windows,

the spiders dangling from their silver bridges,

the wasps lighting on the branches of the cedar bushes

as they waited for me to make a dash for the screen door.’’

— From “The Long Heat Wave,’’ by Jeff Friedman, a poet and professor based in West Lebanon, N.H.

1889 map

‘Unseen energy and forms’

“Wave Function I’’ (1993) (Vitreograph print from glass plates), by Mildred Thompson (1936-2003), in the show of her work, “Cosmic Flow,’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art through Nov. 27

The gallery says:

“Mildred Thompson sought to represent natural phenomena through a distinctly unique language of abstraction. Her dynamic mark-making, color, and compositions visualize the force of unseen energy and forms in the universe, as reflected in this suite of 14 prints, on view at the NBMAA for the first time ever.’’

Llewellyn King: Show the children’s shattered bodies

Memorial to the 19 children murdered by means of an assault rifle at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, on May 24. Two teachers were also murdered.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

America, spare me your thoughts and prayers. Get off your backsides and do something. Wringing hands over the gun lobby, lamenting the love of guns by so many Americans, these won’t do anymore.

The best argument against a bad argument is a better argument. Let us unpack that argument and make it.

I understand the love of guns. I grew up in Africa and I enjoy firing them, love handling them, thrill at their majesty, and admire their craftsmanship. When you handle a firearm, you are handling something awesome, refined power in a form that you can carry.

Therefore, let us start the argument for a new gun regime by eschewing any idea that we are going to ban guns outright, take them away from their owners and collectors who treasure them; no federal marshals will be going door to door confiscating weapons.

You can dream of that, but it won’t happen. You can dream that like Australia, Britain and most of Europe, guns will be kept under lock and key for the enthusiasts. It won’t happen either, though we can start down that road by ending the disingenuous claim that guns make you safe.

Instead, dream of a country where certain guns aren’t available to the public; where guns have better safety devices; where our children aren’t slaughtered, whether it is in Uvalde, Texas, or Newtown, Connecticut; and where the Constitution is honored as written.

First, we should clamp down on assault rifles, designed for use in war, not for sport or self-defense. We should cherish marksmanship, even teach it in schools, which is where I learned to shoot one round at a time. We should inspire the National Rifle Association to return to its original purpose: teaching marksmanship and gun safety.

We should disentangle masculinity, patriotism, fear of government and love of freedom from the possession of automatic weapons, now so promiscuously available. Buyback schemes could take millions of them off the streets.

I offer these as ideas, but they’re not prescriptions. Before we solve the gun carnage in homes, in schools and other places, and on the streets of our great cities like Chicago, we need to think. We need to think about what can be done, not what is inarguably out of reach: With 400 million guns in private hands, to think about confiscation is insane.

Some more thoughts:

Traditionally, social engineering has been practiced through taxation: Introduce it to guns. Tax gun sales heavily, just as we tax liquor and tobacco. But exempt gun clubs, where weapons are kept safely, as happens in many countries.

Then tax ammunition equally severely, but exempt ammunition used at ranges and in controlled gun-sport environments.

Draw a firm line between sporting weapons and automatic weapons of mass destruction, which is what they are. A quail hunter in Georgia shouldn’t have a problem applying for and getting a tax exemption on a shotgun and ammunition.

Take the profit out of selling guns. Eight states operate liquor stores. That worked fine when I lived in Virginia, and it did offer society some control; a kind of check on excess because there is no pressure to make a profit.

If you think nothing can be done because of the Second Amendment, go to the Constitution and read it. Over the decades, it has been alleged to extend a banal entitlement for all and any to carry the latest military weapons. The framers couldn’t have intended that because they couldn’t have conceived of the vast improvement in the lethality of weaponry that has occurred over time.

The bit about “a well regulated Militia”? Let us have some realistic originalism about what the framers meant.

It is a tough thing to do, but the media can make the case for gun-smarts by showing the shattered bodies of the little victims: torn limbs, scattered brains, young, beautiful, innocent, precious blood everywhere.

If we don’t get gun-smarter, this will be a new normal: dead children, randomly slaughtered, sometimes by children. Thoughts and prayers will neither save their lives nor ameliorate the unbearable suffering of their parents. They are weeping today in Texas. Where will they weep tomorrow?

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

There’s never enough

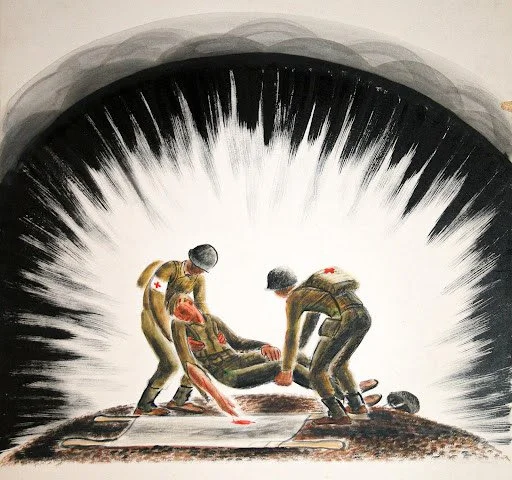

Detail of “Give Your Blood, They are Giving Theirs (Sketch for Blood Donation Poster)” (watercolor on cardboard; 1944), by Virginia Lee Burton Demetrios (1909-1968). Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.

A charming guide on a New England road trip

William (“Willit’’ ) Mason, M.D., has written has a delightful – and very handy -- book rich with photos and colorful anecdotes, called Guidebook to Historic Houses and Gardens in New England: 71 Sites from the Hudson Valley East (iUniverse, 240 pages. Paperback. $22.95). Oddly, given the cultural and historical richness of New England and the Hudson Valley, no one else has done a book quite like this before.

Get a copy of the book and hit the road.

The blurb on the back of the book neatly summarizes his story.

“When Willit Mason retired in the summer of 2015, he and his wife decided to celebrate with a grand tour of the Berkshires and the Hudson Valley of New York.

“While they intended to enjoy the area’s natural beauty, they also wanted to visit the numerous historic estates and gardens that lie along the Hudson River and the hills of the Berkshires.

“But Mason could not find a guidebook highlighting the region’s houses and gardens, including their geographic context, strengths, and weaknesses. He had no way of knowing if one location offered a terrific horticultural experience with less historical value or vice versa.

“Mason wrote this comprehensive guide of 71 historic New England houses and gardens to provide an overview of each site. Organized by region, it makes it easy to see as many historic houses and gardens in a limited time.

“Filled with family histories, information on the architectural development of properties and overviews of gardens and their surroundings, this is a must-have guide for any New England traveler.’’

Dr. Mason noted of his tours: “Each visit has captured me in different ways, whether it be the scenic views, architecture of the houses, gardens and landscape architecture or collections of art. As we have learned from Downton Abbey, every house has its own personal story. And most of the original owners of the houses I visited in preparing the book have made significant contributions to American history.’’

To order a book, please go to www.willitmason.com

Don Pesci: Conn. should impose death penalty for mass murderers

Police at the site of the Sandy Hook massacre, Dec. 14, 2012.

VERNON, Conn.

Following the May 24 massacre (19 children; two teachers shot to death) in Uvalde, Texas, eerily similar to the Sandy Hook slaughter, in Newtown, Conn. (20 children, six staffers shot to death), in 2012, the state’s two U.S. senators, Dick Blumenthal and Chris Murphy, have been out on the political stump pedaling their solutions to mass murders

Democrat Gov. Ned Lamont, we find from a news report, “has been pushing for gun restrictions earlier this year, but the recent legislative session expired in early May without action.” The report quotes him: “… there are so many illegal guns on the street right now. I’d like to think we could have done a better job here in Connecticut and send a message far afield, especially when it comes to those ghost guns.”

Was Lamont suggesting that the elimination of ghost guns would have prevented the most recent slaughter of the innocents in Texas? Was he suggesting that black-market gunrunners would cease and desist their already illegal activities should Congress pass gun laws favored by Blumenthal and Murphy?

One almost feels indecent in pointing out that ghost guns played no part in the assault on elementary schools in Texas or Sandy Hook. The elimination of ghost guns may provide a solution to some problem – but not this problem.

Another story in today’s paper, “Schumer rips GOP after school shooting in Texas,” reports that New York Sen. Charles Schumer has implored “his Republican colleagues to cast aside the powerful gun lobby,” the National Rifle Association (NRA), “and reach across the aisle for even a modest compromise bill. Schumer is quoted: “If the slaughter of schoolchildren can’t convince Republicans to buck the NRA, what can we do?”

In the face of a still raw mass murder, Schumer might try to temper his politicking. Neither of the mass murderers in Texas or Sandy Hook were responsible gun owners, and it is doubtful that either were dues-paying members of the NRA.

Generally we do not blame bank robberies on banking associations. Schumer is asking us to believe that, in respect of mass shootings, it is better to do something – anything, though his plan may not reduce mass murders or urban killings -- than to “do nothing at all.”

Following the Sandy Hook massacre, Connecticut legislators, arguing that “something must be done,” passed a slew of legislation regulating gun sales. Those laws have had no appreciable effect on multiple killings in Hartford, the seat of the General Assembly. And there are those in the state who argue that if you cannot pass a bill preventing 14-year-old-children in urban areas from shooting other 14-year-old-children in urban areas, you will not be successful in curbing mass shootings anywhere in the state.

What might such a bill look like?

In Sandy Hook and Texas, both killers were young men from broken households who spent an inordinate amount of time on the Internet indulging their violent tendencies.

The Sandy Hook killer shot his mother, stole her guns, an AR-15, a shotgun, and an automatic pistol with which he killed himself, and shot his way through the front entrance to Sandy Hook elementary school.

He was a loner, monkish, somewhat withdrawn from school life and other life-affirming social interactions. He had no arrest record and there were no reports that he was under mental duress.

The Texas murderer procured his guns legally, shot his grandmother in the face and proceeded to an elementary school that was, so to speak, a gun-free zone, where he locked himself in a room with his victims and opened fire.

endment rights, cherished by reporters and political commentators.

Nor have partisan politicians – Murphy, in particular, now seems eager to entangle all Republicans in the U.S. Senate in a far-fetched moral complicity in mass murders -- suggested sensible precautions, the hardening of access to schools, for instance. We post armed interveners in banks because we wish to prevent bank robberies and secure valuable assets. Are our children less valuable than our bank account savings?

In the Texas mass-murder case, we now know, the school was not properly hardened to prevent a mass assault; the school’s guard was not present at the time of the attack; multiple doors were unlocked; police waited too long before storming the building; neither children nor school staff were taught how to respond in case of such attacks; the perimeter fence surrounding the school was easily penetrated; there was no centrally activated room locking system available – in other words, mistakes were made.

It may be nearly impossible to prevent every instance of mass murder in schools, just as it is impossible to prevent all bank robberies. But illegal activities in both cases can be justly punished. And the most successful tool of mitigation, we know, is the swift and certain imprisonment of convicted criminals. Just punishment does deter crime – which is why senators such as Blumenthal, Murphy and Schumer provide us with an endless stream of laws designed to frustrate unwonted activity.

But, as yet, no one is screaming from the rooftops that just punishment delayed is just punishment denied. Would Blumenthal and Murphy welcome a reinstitution of Connecticut’s death penalty for mass murderers?

Likely not, but why not? Connecticut’s Supreme Court years ago found that even a just capital punishment violated an assumed moral resistance on the part of Connecticut citizens against capital punishment. Since then, capital punishment has become a very back-bench issue in Connecticut politics, the legislative equivalent of the sin that dare not speak its name. Some suspect that moral exemplars among our politicians no longer believe in the utility of just punishment. It is much easier politically to find guns rather than murderers guilty of and punishable for mass murder.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Fungus in the forest

“Sulphur Shelf” (oil on canvas), by Owen Krzyzaniak Geary, a New York-based painter, in his show “Night Vision,’’ at Two Villages Art Society, in the Hopkinton, N.H., village of Contoocook (his hometown), through June 18.

He says:

"Paintings of fluttering bats and glowing fungus [that] remind me of exploring the forest at night when I was younger."

Stone arch bridge over the Contoocook River in the village center.

Hopkinton Fair in 2016.

On which the lichens grow

"Many New England stone fences built between 1700 and 1875 were laid by gangs of workers who piled stone at the rate of so much a rod. Edwin Way Teale says that in the latter years of the past century, before economic and social developments began obliterating some of the walls, there were a hundred thousand miles of stone fences in New England. Even today, for many of them, the only change has been the size of the lichens, those delicate rock-eating algae that can live nine hundred years."

— William Least Heat Moon, in Blue Highways

Gamble, drink, smoke

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s good to see an effort by some local casino workers to get those establishments to ban smoking. Smoking not only causes lung cancer and other illnesses in smokers, it can sicken nonsmokers near them. That’s particularly true for casino workers, who must be there 40 hours a week.

Casino operators love smokers because they tend to be more prone to addictions in general, including gambling and booze. Drinking, smoking and gambling neurologically reinforce each other.

Consider that Spectrum Gaming Group estimates that 21 percent of Atlantic City casino visitors are smokers but account for 26.1-31.3 percent of the casinos’ revenue. The casino owners and executives, seeking to maximize profits, and the states, seeking to maximize tax revenues from the industry, don’t want to discourage any high rollers.

As with such things as legalizing “medical” and “recreational” marijuana (which in some people is a gateway to harder drugs) – more tax revenue! -- government promotion of gambling tends to poison society.

If you think that drivers are bad now, just wait until full-bodied legalized “recreational” marijuana takes over the roads.

‘Tension beneath the calm’

“Spring Fling 2’’ (oil, cold wax on wood), painted in 2020 by Dona Mara Friedman, who lives in tiny Rupert, Vt.

Ms. Friedman says:

“{My] recent work is influenced by my surroundings, as solitary time became all the more important in 2020. Living in a country setting surrounded by the wonder of nature I spend time watching the changing light, wind rustling the tree leaves and rain on plants that provide a full palette of colors. These careful observations become take off points for work that is process based while holding the intention of communicating an emotional response. The choosing of materials, marks, colors and images is directed by my interior dialogue and a continual desire to experiment.

“This quote from Richard Diebenkorn, a painter who inspires me, resonates with my findings.

“‘I came to mistrust my desire to explode the picture and super charge it in some way – what is more important is a feeling of strength in reserve – tension beneath calm.’

“The tension beneath the calm speaks clearly to me of my experience in modern day living. The paintings offer the viewer a possibility to be drawn in, taking another look and perhaps understanding this artist’s view of the complexities of modern life.

“This connection of artist to viewer completes my process.’’

Rupert is in the Taconic Range, whose high point, 3,840-foot Mt. Equinox, is in nearby Manchester. Vt.

Cynthia Drummond: Learning to bear it in southern N.E.

An Eastern Black Bear. Increasingly common in the eastern U.S. wherever suitable wooded habitat is found. It’s a large-bodied subspecies. Almost all specimens have black fur while a few may sport a white blaze on the chest.

Photo by Cephas

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

In what has become a rite of spring, Rhode Island residents are once again reporting black bear sightings. This is the time of year when young, male black bears are searching for mates, and because there isn’t much natural food available yet, they will eat just about anything they find, including bird seed.

David Kalb, supervising biologist in the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Fish and Wildlife, said it’s difficult to predict how much the bear population in Rhode Island will grow, but with no natural bear predators and abundant food sources, it is expected to get larger.

“It’s hard to say for sure if there are more of them,” he said. “We anticipate that over the next five to ten years, we are going to see an increase in the number of bears, but because we’re still at such a low population level, it’s hard to evaluate what are the true numbers.”

Hunted relentlessly by European settlers, black bears had disappeared in Rhode Island by 1800, but began to rebound as bear hunting ended and their habitat was restored. With healthy bear populations in Massachusetts and Connecticut, Kalb said it wouldn’t be long before sows and cubs join the transient male bears and begin to settle in Rhode Island.

“We have thus far been lucky, honestly, not to see some sows and cubs, given the number of years we’ve had lone males in Rhode Island and with the density of bears in eastern Connecticut and southern Massachusetts,” he said. “But they will be here. We have great habitat for bears and with them being populated on the borders, it won’t be long before we do start to see them.”

Black bears do not truly hibernate, instead going into a lowered metabolic state known as winter torpor from which they frequently emerge during warm spells. As Rhode Island winters get warmer, bears could remain more active year-round, like bears living in southern states.

Bears, many of them plundering bird feeders, have been observed throughout southern Rhode Island this spring. Despite DEM’s efforts to persuade residents to remove bird feeders in early March, many people aren’t getting the message.

“We like to get people’s attention before they have an incident, but sometimes, having a neighbor’s bird feeder hit will often encourage homeowners to remove their bird feeder or if they see it happen in the neighborhood, generally you can get that neighborhood on board pretty quickly,” Kalb said. “But without having any incidents around your house or in your neighbors’ area that you know about, it’s going to be hard to convince people that they’re in bear area right now.”

What Kalb means by “bear area” are the more rural, wooded northern and southwestern parts of Rhode Island.

“It’s a rare occurrence, and it has happened, where a bear would move closer to the city just because they’ve been scared out of a certain area, or for some reason or another, but generally, I would not consider that bear habitat,” Kalb said.

As executive director of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, David Gregg knows more than the average Rhode Islander about black bears and their habitat, so living near the Saugatucket River in the more urban municipality of South Kingstown, he was not expecting to see one in his back yard.

“I went out after dinner, and I wanted to do a little birding, so I grabbed my binoculars and I started out into the field by my house and I got 30 feet from the back door and I saw something large and dark brown through the woods, and there was a bear, about 100 feet from me,” he said.

Gregg went back to the house to tell his family and they watched it from a safe distance.

“It could tell we were there,” he said. “It sort of sniffed and it decided to move away from us and it gradually disappeared into the bushes.”

Gregg said he wondered what had drawn the bear to the more urban neighborhood. He got his answer the next day when he found the bear’s scat — full of sunflower seeds, almost certainly from bird feeders.

With education key to coexisting with bears, DEM recently partnered with BearWise, a company founded by bear biologists in the southeastern United States that specializes in public outreach.

“They’ve done a lot of really nice publications and produced other really interesting and user-friendly packets about living with black bears,” Kalb said.

DEM chief public affairs officer Michael Healey said it was important for Rhode Islanders to begin planning now for a future with bears.

“Where we are now as a state is, people see bears, which isn’t a problem or doesn’t pose a safety threat in and of itself, and there are some bear interactions with humans, probably livestock and pets, and agricultural products, beehives, feeds, that may at times constitute a problem,” he said. “We want to educate Rhode Islanders that these kinds of scenarios will become more typical as more bears become established in Rhode Island.”

Bears are not usually interested in encounters with humans.

As furry and charismatic as black bears may be, they are also large, powerful wild animals. Male black bears, or boars, can weigh up to 450 ponds and sows can weigh up to 250 pounds.

“Most of the time, we will never have major issues with bears,” Kalb said. “What we will have, though, is damage to people’s property, beehives and gardens, chicken coops and things along that line where a bear is looking for an easy meal and someone hasn’t taken care of their stuff and the bear takes advantage of that.”

Bears are not interested in encounters with humans and will usually run away from people, but human-bear conflicts sometimes do occur. DEM describes a dangerous bear as “one that has attacked or has attempted to make personal contact with a person or an attended [leashed] pet.”

It is illegal to feed or kill black bears in Rhode Island, and coexistence with bears involves removing food sources that will attract them.

“It’s important to recognize that bears were here in Rhode Island, historically,” Kalb said. “This is their natural zone. We are surrounded by bears from Maine to Florida and it’s not going to be long before Rhode Island is considered a standard bear state, just like every other state, and we’re going to have breeding and bears will be a common site. They’re here. They’re a natural part of the ecosystem. They serve a function in Rhode Island and people should be excited about that and look forward to opportunities to observe bears from a safe distance.”

Gregg agreed that it wouldn’t be long before Rhode Island had its own resident black bear population.

“Eventually, the sows’ range, they roam less than the males, but they roam enough to find good food and better den sites,” he said. “Yeah, they’ll get here. It’s only a matter of time.”

Healey said DEM planned to ramp up its effort to educate residents about the importance of removing food sources that attract bears.

“We’re going to become more vocal about this issue because we really don’t want to see it escalate to the point where bears are attacking pets and livestock, or, God forbid, injuring or killing a person,” he said. “We know it’s going to take time — years, really — to prime this message with the public, but we’re committed to doing that.”

Cynthia Drummond is an ecoRI News contributor.

Enjoying Quincy’s 19th Century ‘multiplicity of nature’

Still pretty: View looking east on Quincy Bay

— Photo by Sswonk

Quincy, Massachusetts (oil on canvas), by Childe Hassam, 1892

“Winter and summer, then, were two hostile lives, and bred two separate natures. Winter was always the effort to live; summer was tropical license. Whether the children rolled in the grass, or waded in the brook, or swam in the salt ocean, or sailed in the bay, or fished for smelts in the creeks, or netted minnows in the salt-marshes, or took to the pine-woods and the granite quarries, or chased musk-rats and hunted snapping turtles in the swamps, or mushrooms or nuts on the autumn hills, summer and country were always sensual living, while winter was always compulsory learning. Summer was the multiplicity of nature; winter was school.”

Henry Adams on growing up in and around Boston, in The Education of Henry Adams. Adams ( 1838-1918) was an American historian and a member of the Adams political family, which included his paternal grandfather, President John Quincy Adams, and great-grandfather, President (and a U.S. founding father) John Adams.

Adams’s book, published posthumously, won the 1919 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction and The Modern Library placed it first in a list of the top 100 English-language nonfiction books of the 20th Century.

As a boy he spent his summers in Quincy, just outside of Boston but large parts of which were still quite bucolic then.

Quincy Quarries Reservation, in West Quincy.

— Photo by Sswonk