William Morgan: Block the schlock in Route 195 relocation area

(Photos are by William Morgan.)

The relocation of Interstate 195 away from Fox Point was one of the reasons my wife and I chose to move to Providence. The old highway was still a scar marring the base of College Hill when we came here city shopping 20 years ago. That the city had decided to remove that relic of misguided transportation planning convinced us that Providence was an unusually smart and creative town–one with a clear-eyed sense of itself and proud of its rich heritage.

The Providence River where Interstate 195 used to cross.

Now, in a frenzy of construction, the reclaimed land is being developed and a pedestrian bridge will soon link both shores of the river. In early May the I-195 Commission held a public meeting to review three applications to develop the open space between Main, Canal and Wickenden Streets.

While the proposals varied in how many parcels they would cover, any construction here would have a tremendous impact. Given the most important undeveloped site on the East Side, one might expect that the city had solicited some of the world's most imaginative and respected designers. Alas, no. Two of the schemes are no better than the typical schlock found in any suburban office park.

The 160 luxury apartments of Post Road Residential were touted as having “distinctive amenities.” The Connecticut-based developers identified themselves as “the blue chip apartment developer in the northeast.” Despite such hyperbole, few of their completed apartments that Post Road illustrated made the heart race. Images of neighborhood details seemed disingenuous.

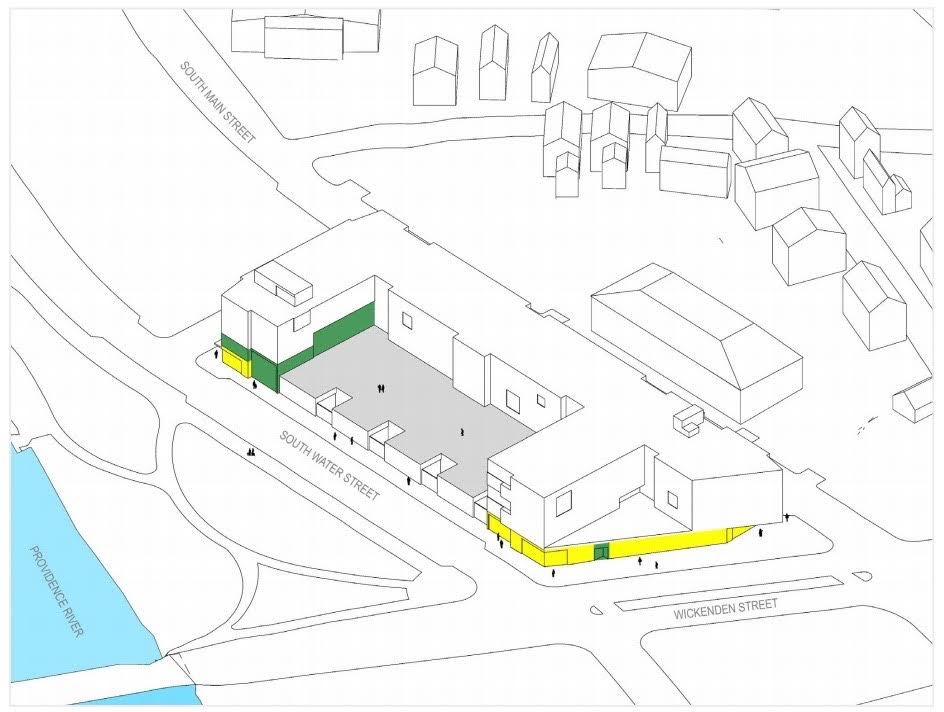

Schematic of Post Road Residential.

Bargmann Hendrie + Archpetype, Post Road’s architects, claim that their work is marked by “cost-effective design,” but this project has nothing to offer other than giving the developers a foothold in Rhode Island. Even the most build-anything-as-long-as-you-build-it diehards at the commission hearing could sense this was an also-ran entry.

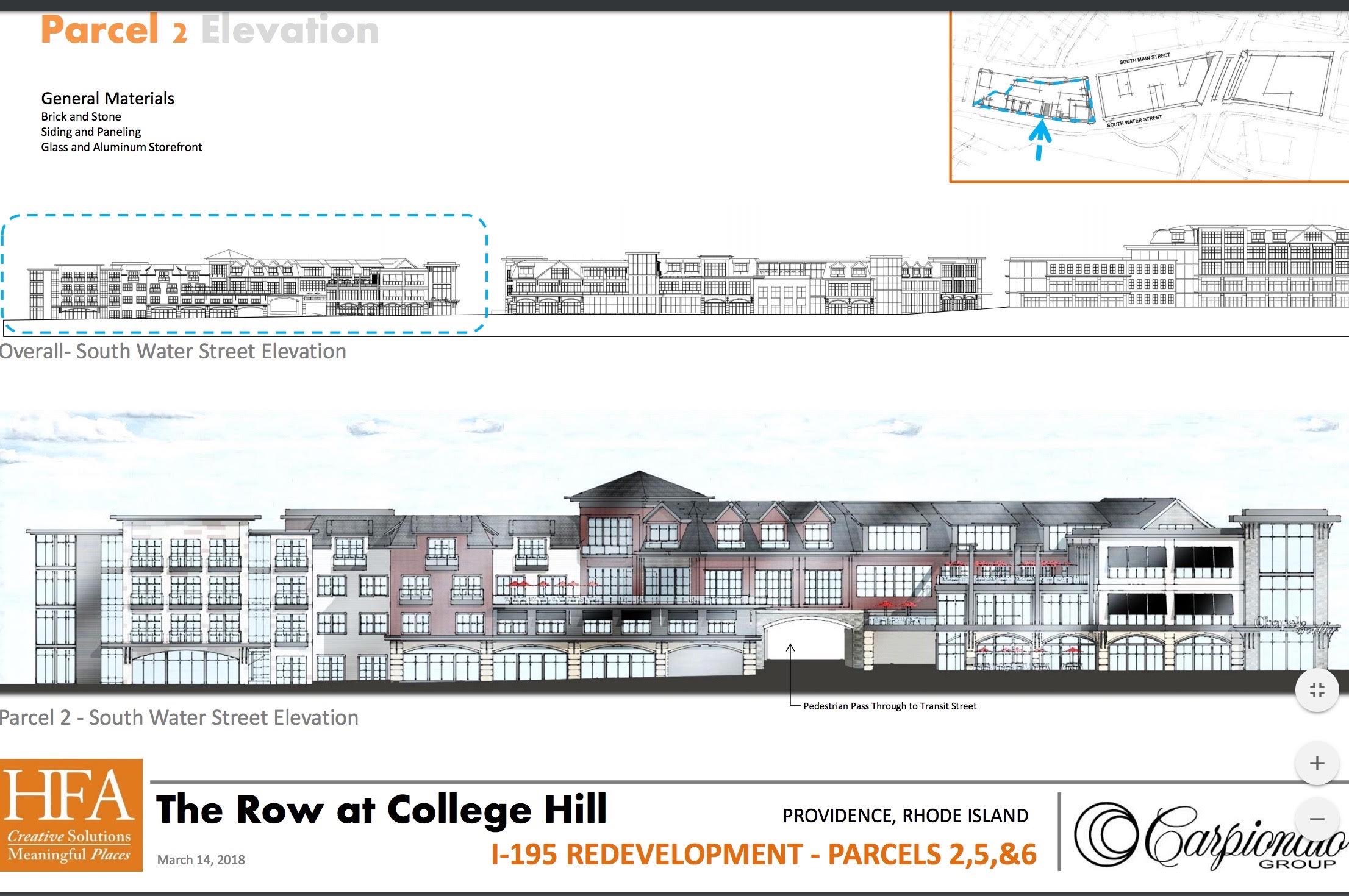

The Carpionato Group went for an over-the-top sales pitch for The Row at College Hill, a scheme laced with clichés and too little in the way of good design. Carpionato president Kelly Coates declared that this would be a “lifestyle development – a catalyst for city and state” and would attract “the best of the best tenants.” But it was difficult to see beyond the box-store quality of this multi-parcel behemoth – a stepsibling of their Chapel View shopping center, in Cranston.

The Row at College Hill.

Lou Allevato, of Caprionato’s architecture firm HFA, declared, “We need to inspire with great architecture.” Yet there was none on offer. In a bit of hopefulness, HFA’s moniker is Creative Solutions Meaningful Places, a firm “focused on designing for the customer experience.” Headquartered in Bentonville, Ark., HFA designs for Walmart (which is based in Bentonville), Slim Chickens, 7-Eleven and Alex + Ani. In Providence this team has given us the Home Depot and University Market Place.

To be fair, the current Row at College Hill is a remake of the one originally proposed in 2013. That scheme was more thoughtful and urbanistically responsible. Instead of large blocks of building, the housing was broken up into several smaller units, the skyline was varied, and there was a communal courtyard in the center of the largest parcel. Although the new configuration of the Row apparently satisfies some neighborhood concerns, it would contribute far less to the cityscape.

The Row at College Hill, 2013 proposal.

Is this the level we aspire to for this near sacred plot of land? This place is part of our urban patrimony. It is where the Providence River joins Narragansett Bay. It has views of several bridges, as well as the iconic triple stacks of the power plant, and it is a strategic entrance to College Hill and Fox Point.

Rather than the tired mantra of “Jobs, Jobs, Jobs” and boasts of square footage inflicted on other cities, the Spencer Providence presentation was three dimensional, considering appearance as well as economics. The architect, James Piatt of Piatt Associates, made the balanced and provocative presentation.

Spencer Providence.

Based in Boston, the firm has a solid record as a builder of housing, schools, hotels and restaurants. Prior to establishing his own firm, the MIT-trained Piatt worked for the legendary urban developer James Rouse and with architect Benjamin Thompson on Faneuil Hall Market. The architect walked the audience through what the mixed-used village might actually feel like. His selection of historical images strongly suggests that Piatt understands Providence’s history, scale and unique vibe.

Spencer Providence.

As opposed to the monolithic blocks of suburban junk offered by Carpionato and Post Road, Piatt’s town houses, hotel and retail establishments are knitted in a multi-faceted tapestry of palettes, materials, and massing, offering the “kind of variety this neighborhood deserves.”

How unfortunate that the I-195 Commission does not have three equally good proposals to chose from. Whatever we build on this prime location will be with us, for better or worse, for a long time to come. Good design is a better investment, and there should be just as many jobs to build a notable piece of architecture as a turkey.

We need to ask when will Providence accept that truly inspiring and lasting development is more than mere real estate, union jobs and lowest-common-denominator building wrappers.

Willam Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian and author.

Chris Powell: A city cop, now retiring, who didn't get cynical

Hartford, from across the Connecticut River.

Hartford's deputy police chief, Brian Foley, the department's spokesman for the last five years, will retire this month, so the other day he went on Ray Dunaway's morning show on WTIC-AM1080 for a half hour to reflect on his 23 years with the department.

Foley recounted riding a bicycle on a neighborhood patrol beat, working in the homicide division, and then explaining the department to the public. He described his love for the city, his family's involvement in police work elsewhere, and his intention to stay connected with Hartford.

Less than an hour after Foley walked out of the studio, a fellow Hartford officer, Jill Kidik, was repeatedly stabbed in the neck and nearly murdered by a deranged woman at an apartment building downtown, a crime that horrified the whole state. (Miraculously Kidik is expected to recover fully.) That night a man was shot to death a few blocks away on Hartford's north side.

It was just another day in Connecticut's capital city, and because so much of the news coming out of Hartford is crime, Foley may have become the city's most recognized figure throughout the state. But the good news from Hartford has been the increasing accountability of the city's police.

This has been far more than the department's timely provision of incident information, the work that has made Foley famous. It also has been the department's striving to connect with the disadvantaged community it protects, a community full of people who are or have been on the wrong side of the law, a community suspicious of law enforcement and not terribly impressed with the law itself.

Such a community easily can engender rage in those assigned to police it. (Indeed, it is a bit of a wonder that the deranged woman who nearly murdered the Hartford officer the other day wasn't herself beaten to a pulp during the officer's rescue.) Sometimes that rage has burst out among Hartford officers on duty, but it is also a bit of a wonder that in recent years the Hartford department has been quick to identify misconduct and publicly discipline and dismiss officers.

Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin noted this in his comments on Foley's retirement. Foley, the mayor said, "has helped our department set a national standard for transparency, accountability, and engagement, and he has been deeply committed to the mission of building trust between our police department and the community."

Apart from being candid and accessible, Foley may have been even more remarkable as a police spokesman for his compassion for some of the young perpetrators whose arrests he answered for. He would acknowledge the handicaps imposed on them by their neglectful upbringing, handicaps worsened by their getting stuck in the criminal-justice system. He rooted for their rehabilitation, not their imprisonment.

Foley, a Tolland resident, didn't get cynical, but cops have to be forgiven for that. In an old episode of Law & Order the detective played by Jerry Orbach enters a squalid apartment with several other officers. No one else is inside except an abandoned and crying baby. Orbach asks, "How about if I just take him to Rikers (the New York City jail} now?"

Of course, the scene could have been shot in Hartford.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

'A myriad of shadings'

Robert Frost's writing cabin in Ripton, Vt.

"Except for the splashy displays of autumn, there is little that is exhibitionist or uncompromising about the Vermont landscape. It encourages moderation and common sense. The mountains are small and of human proportion. In summer -- Frost's time of year in Ripton -- the scenery, at first glance, is all green. But look closely at the lime-tinted undersides of the beech leaves, the pale yellow of the meadowsweet and the hobblebush, the black shades of the fir needles and the faintest intimation of white dotting the 'white pines.' Within this broad spectrum of green is actually a myriad of shadings and subtleties. Inspect and observe, then remain watchful, says the landscape.''

-- From a Sept. 1, 1991, New York Times article headlined "Robert Frost's Vermont''.

Naval War College a potent force in New England

Part of the U.S. Naval War College campus.

A "Newport Report'' article by Robert Whitcomb, from GoLocal24.com

Newport Mayor Harry Winthrop told me the other week:

“The City of Newport, the Navy and especially the Naval War College {founded in 1884} are

inextricably linked through our long history of association and

cooperation. We are partners in every sense of the word and the

economic impact of having such a prestigious institution in our

community is in the tens of millions of dollars annually.’’

The college’s founding president, Admiral Stephen Luce, described it:

“The War College is a place of original research on all questions related to war and to statesmanship connected with war, or the prevention of war.’’ This has come to mean that the institution addresses a very wide range of subjects beyond the purely military, such as geopolitics, diplomacy, economics, climate and the implications of accelerating technological change.

John Riendeau, who oversees the defense-industry sector for the Rhode Island Commerce Corporation, noted: “The War College gets the best and the brightest’’ of the military. He said the state doesn’t pull out the specific economic impact of the NWC from the total Navy impact on the state even as he cited its big “intangible’’ benefits to civic life in the region.

Rear Admiral Harley

I spoke with Rear Admiral Jeffrey Harley, the War College’s president, the other week in his office overlooking Narragansett Bay. He emphasized that it’s a graduate-level university, granting master’s degrees and a range of certificates. “We’re on par with Ivy League schools’’ in the quality of teaching and scholarship, he said.

For that matter, the NWC has relationships with such elite institutions as Brown, Harvard, Yale, MIT, the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts, Princeton and King’s College, in London. This includes War College professors teaching as adjuncts in some of these schools. The War College is exploring possible joint Ph.D. programs with some of these schools, too. For its foreign students, the NWC has a partnership with Newport’s Salve Regina University in which such students get master’s degrees in a number of disciplines.

An example of local joint academic ventures is the NWC’s joint conference with and at Brown May 31-June 1 titled ‘‘2018 Women Peace and Security: Promoting Global Leadership’’.

The institution is moving toward adopting such traditional university/college practices as tenure for professors. And it wants Congress to allow copyright protection for professors’ work, which would be a selling point to recruit and keep more of the best scholars. Civilian institutions usually provide such protection. It’s all part of the drive, now led by Admiral Harley, to, in his words, “normalize’’ the institution to make it even more of a prestigious research university.

This complex institution is much more heterogeneous than most of the public realizes. Consider that a breakdown of the college’s current Senior Course, with 224 students (there are a total of 545 resident students this academic year) showed:

25 percent of the student body came from the Navy; 18 percent from the Army; 12 percent from the Air Force, and 2 percent from the Coast Guard. 21 percent were foreign students and 13 percent were civilians (usually mid- or high-level federal government employees). Many of the foreign students, as with the Americans, go on to become very high-level leaders in military and civilian life in their home nations. The faculty is a mix of military and civilian teachers.

Admiral Harley repeatedly cited the War College’s “giving back to the community.’’ This has included NWC personnel speaking at local schools and other venues, such as the Eight Bells Lecture Series at the Seamen’s Church Institute, in Newport; at such organizations as the Providence Committee on Foreign Relations, and campus tours for local high-school students. He emphasized: “We’re very integrated with the community.’’ (I asked him why there were fewer events on campus that local civilians could attend than I remember from years ago. He cited increased security concerns as “the new reality’’ in the post 9/11 world.)

More outreach: On May 8, the War College ran a program for 26 students of the Rogers High School (in Newport) Academy of Information Technology. The event featured a technology-oriented introduction to wargaming, including hands-on experience with two NWC games. Then there’s the 2018 Summer STEM Camp at the college for high school students. The July 15-20 in-residence program, called Starship Poseidon, is to “provide insight into career opportunities in science, technology, engineering and math.’’

Admiral Harley cited the NWC’s sending its foreign students to speak at local schools, noting that some students at the latter might otherwise have little opportunity to hear perspectives on international affairs. And many of the foreign students bring their families to live with them during their time at the War College; they, too, engage closely with the community. War College personnel and students meet with many community leaders.

Commander Gary Ross, a public-information specialist at the NWC, said there were about 4,000 War College alumni in southeastern New England. They bring great expertise in long-established and relatively new (such as cybersecurity) technological and managerial disciplines applicable to large and small, established and start-up business. Their presence provides rich opportunities to enhance civic life and economic development in southeastern New England.

Llewellyn King: A third way out of the U.S. immigration mess

To me, there is something especially savage and cruel about deportations. It reminds of what I saw in colonial Africa, or in South Africa, or touring the Auschwitz concentration camp. Armed men and women coming by surprise to rip apart a family, to condemn people to a future they had braved so much to escape, evokes all the horrors of history. The rough brutality of one person taking charge of another appalls, twists the gut and stops heart.

Even if sanctioned by law, the unfettered power of the state and its officers moving against an individual is profoundly ugly. The fact that those seized have broken the law doesn’t seem, in most cases, to justify ending the order and hope of their modest lives.

Yet I don’t believe any nation should allow conquest by immigration that is a threat to one’s culture, one’s language and one’s own sense of place. I believe that there should be legal immigration, screened immigration. Our natural rate of population replenishment is inadequate.

Against the backdrop of vast shifting populations around the globe, the United States has only a modest problem. The illegal immigrant inflow, particularly across the southern border, has dwindled. So the issue is the estimated 11 million to 12 million illegal immigrants who are here, have put down roots and are often raising American children.

Their fate is bitterly divisive: on one side, liberals and groups that speak for immigrants wanting amnesty and citizenship and on the other, conservatives demanding that our immigration laws are immutable, and the illegals must be arrested and deported.

Mark Jason, a retired IRS inspector from Malibu, Calif., looked at the problem from a taxman’s point of view through the Immigrant Tax Inquiry Group, which he founded in 2008.

Jason was concerned with the negative effect illegal immigrants were having on local communities, straining budgets and overwhelming social services. This kind of pressure has led many local entities to act against these people, denying them services, from driving licenses to schooling.

Jason knew from his research that many illegal immigrants, who came here to get a better, safer life, want eventually to return to their homelands. Trouble is they are immobilized in the United States, particularly if they have family here. If they visit their homelands, they can’t get back into the United States.

Jason believes a creative tax could defuse the illegal immigrant argument and stabilize life for what have become people of the shadows.

His plan, his third way, will:

—Grant all illegal immigrants who want to work a permit, called a REALcard (short for respect, equality, accountability and legality) that is valid for 10 years and renewable.

—Impose special taxes — 5 percent on the wages of the workers and 5 percent on the same wages to be paid by the employer — which would go to the hurting local communities.

Jason calculates that his tax will raise $210 billion over 10 years and that this money should be earmarked for communities hosting large numbers of immigrants.

For a decade, Jason has been imploring immigration groups, think tanks and Congress to consider his plan. Next week, he will be holding an information session on Capitol Hill to investigate various perspectives on immigration. His plan is to have a discussion on immigration focused on sound public policy, placing the interests of U.S. taxpayers first and treating all the stakeholders with respect.

I’ve known Jason for five years and have been astounded by the tenacity of this gentle Reagan Republican and his desire to do the right thing for those caught up in the immigration gyre, to relieve the acute artisan labor shortage, and to help counties and cities with their added illegal immigrant burdens — the new money going to education, health care, policing, jails and social services.

Legalize the illegal immigrants and some will go home early. Data show that about half will return eventually to their homelands.

To my mind, Jason’s self-funded Immigrant Tax Inquiry Group is offering a solid alternative to the bleak immigrant policy debate — and to the swinging door of the detention center. Illegal entry into the United States in law, so venerated by the deportation enthusiasts, is only a misdemeanor.

Families physically torn apart, deportation and ruin, is a severe penalty for a misdemeanor. Does it fit the crime when there is another way?

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Hopeful architecture

Wilcox-Cutts House, in Orwell. Vt. It was mostly built in 1843.

"Their idiom, their dimension,

was life; they spoke in its terms.

What vigor their houses have! --

deep-based, tall-windowed, updrawn,"

towered, they rise like trees

from thin soil spruced into lawn

and shell-rimmed flowerbed,

toward a more specious air.'

--From "Intimations of Immortality, Cuttingsville, Vermont, 1880,'' by Constance Carrrier

Chris Powell: 'Diversity' Democrats start at the top

With two zillionaire candidates hoping to win their party's primary for governor with pervasive advertising, Connecticut's Republicans aren't the only ones being asked to nominate candidates nobody knows but who want to start at the top.

Connecticut's Democrats are being asked to do it as well, only instead of money, the basis of the pitch to start at the top is "diversity."

In the 5th Congressional District, the candidate endorsed last week by the party's district convention, former Simsbury First Selectwoman Mary Glassman, the party's candidate for lieutenant governor in 2006, is being challenged in a primary by Jahana Hayes, of Wolcott, a Waterbury teacher who was national teacher of the year in 2016. Hayes has no record in public life and her claim on the nomination is frankly that she is black while Glassman is white and the Democratic ticket needs racial diversity. So much for Glassman's having been Simsbury's first Democratic chief executive in 40 years, diversity in political substance.

At the Democratic State Convention last the weekend, ethnic diversity was claimed as justification for a primary for the nomination for lieutenant governor.

Former Secretary of the State Susan Bysiewicz, who in pursuit of party unity ended her candidacy for governor to become the lieutenant governor candidate of Ned Lamont, the choice of party leaders for governor, was challenged by Eva Bermudez Zimmerman, of Newtown. Zimmerman is a government employee union organizer who lost a race for state representative two years ago. Her claim on the lieutenant governor nomination is only that she is of Latin American descent and Bysiewicz is white.

What is Zimmerman's expertise for high state executive office and what are her positions on the big issues? Announcing her candidacy, she didn't say and none of her supporters knew, though maybe, after her ethnicity, they think it is enough that she is a government employee union organizer, as if the Democratic Party needs to be even more identified with that predatory special interest.

Lamont has played along with this as much as he reasonably could. He has pledged to have the most diverse state administration in history and he solicited New Haven Mayor Toni Harp, who is black, to run with him as lieutenant governor. Harp would have been not just a "diversity" candidate but a well-qualified one, having been a state senator for many years before becoming mayor -- completely vetted and a known quantity. She declined Lamont's offer and the Democrats had no other well-qualified minority prospect for the lieutenant governor nomination.

Since the last eight years of Democratic rule have dragged state government into insolvency and given Connecticut nearly the worst economy in the country, it may be no wonder that the party prefers to stress race and ethnicity. But such things won't pay the bills.

This year's proliferation of candidates without records in public life emphasizes the usefulness of party conventions for vetting purposes. For conventions test the character of candidates and delegates alike in public, pushing some into betrayals or opportunism.

Further, while primaries properly provide the ultimate democracy in party politics and at last are fairly accessible to candidates in Connecticut, conventions introduce the party to itself and confer the judgment of its most committed members on its prospective nominees. That judgment isn't infallible but it's usually worth something.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

'Constant mirage'

Dunes at Sandy Neck, in Barnstable, Cape Cod.

"Instead of fences, the earth was sometimes thrown up into a slight ridge. My companion compared it to the rolling prairies of Illinois. In the storm of wind and rain that raged when we traversed it, it no doubt appeared more vast and desolate than it really is.....A solitary traveler whom we saw perambulating in the distance loomed like a giant....Indeed, to an inlander, the Cape landscape is a constant mirage.''

Henry David Thoreau, in Cape Cod (1865)

Go with the flow

"Order and Chaos'' (diptych, oil on copper), by Nora Charney Rosenbaum, in the show "Ghost Fish,'' at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, May 30-July 1. She says: "The underlying theme of this group of work is the movement of water as a metaphor for my recent life experiences. Seeking predictability amidst chaos, equilibrium in turbulence, I've been carried along by currents either willingly or with resistance.''

But not at their homes

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

In my view, the Vermont Supreme Court has ruled wrongly in overturning the conviction of William Schenk on a disorderly-conduct charge for leaving Ku Klux Klan flyers at the Burlington homes of two women of color. The First Amendment does not protect such obviously threatening behavior -- at private homes -- by a man representing an organization with a violent, terrorist history. If he wants to give racist speeches and leave flyers with images of burning crosses, robed Klansmen and Confederate battle flags let him do that in a public place, not at the homes of people whose color makes them targets of physical assaults by KKK members.

Free-speech cases can be tough.

Warm enough

"The Mink Stole,'' by Alberta Geyer, in the "2018 Members Juried Exhibition,'' at the Guild of Boston Artists, through June 2.

CEO imperialism on Nantucket

Theodore Robinson's painting Nantucket, (1882) -- way before the modern fat cats arrived to take over much of the island.

From Robert Whitcomb's Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

A rich Nantucket summer resident (and that’s sort of a redundancy these days) is fighting mightily to prevent the Nantucket Land Bank from building a small dormitory for 22 seasonal workers to address in a minor way the deep affordable-housing crisis on that billionaire-dense island, where some workers have had to sleep on floors or in vehicles and shipping containers. The dorm would be 350 feet, but well shielded by trees, from the 5,700-square-foot wooden chateau of David Long, the CEO of Liberty Mutual, the Boston-based insurance company. He calls the place “Summer Wind.’’

Long has hired a bunch of high-priced lawyers to try to kill the project through assorted technical arguments even as the Board of Selectmen and most others on the island support it. Long doesn’t want the peasantry near him.

Long may be typical of the imperial executives who have been running companies (and now the United States) since the ‘80s – obsessed with maximizing their personal wealth above all else and wallowing in conspicuous consumption. They tend to have houses in places such as the Hamptons and Nantucket which, since crowded by other rich people, further inflates their self-importance.

Long was paid about $20 million last year, and, as The Boston Globe famously noted, $4.5 million was spent to renovate his 1,335-square-foot office (throne room?) at Liberty Mutual.

Such folks are making Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard boring. They’re building a Greenwich, Conn., on sand dunes.

The retired general who helped to stop a Wall St. coup against FDR

Gen. Smedley Darlington Butler.

From OtherWords.org

Many Americans would be shocked to learn that political coups are part of our country’s history. Consider the Wall Street Putsch of 1933.

Never heard of it? It was a corporate conspiracy to oust Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had just been elected president.

With the Great Depression raging and millions of families financially devastated, FDR had launched several economic-recovery programs to help people get back on their feet. To pay for this crucial effort, he had the audacity to raise taxes on the wealthy, and this enraged a group of Wall Street multimillionaires.

Wailing that their “liberty” to grab as much wealth as possible was being shackled, they accused the president of mounting a “class war.” To pull off their coup, they plotted to enlist a private military force made up of destitute World War I vets who were upset at not receiving promised federal bonus payments.

One of the multimillionaires’ lackeys reached out to a well-respected advocate for veterans: Retired Marine Gen. Smedley Darlington Butler. They wanted him to lead 500,000 veterans in a march on Washington to force FDR from the White House.

They chose the wrong general. Butler was a patriot and lifelong soldier for democracy, who, in his later years, became a famous critic of corporate war profiteering.

Butler was repulsed by the hubris and treachery of these Wall Street aristocrats. He reached out to a reporter, and together they gathered proof to take to Congress. A special congressional committee investigated and found Butler’s story “alarmingly true,” leading to public hearings, with Butler giving detailed testimony.

By exposing the traitors, this courageous patriot nipped their coup in the bud. But their sense of entitlement reveals that we must be aware of the concentrated wealth of the imperious rich, for it poses an ever-present danger to majority rule.

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer, public speaker, and editor of the populist newsletter, The Hightower Lowdown.

CEO imperialism on Nantucket

Theodore Robinson's painting Nantucket, (1882) -- way before the modern fat cats arrived to take over much of the island.

From Robert Whitcomb's Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

A rich Nantucket summer resident (and that’s sort of a redundancy these days) is fighting mightily to prevent the Nantucket Land Bank from building a small dormitory for 22 seasonal workers to address in a minor way the deep affordable-housing crisis on that billionaire-dense island, where some workers have had to sleep on floors or in vehicles and shipping containers. The dorm would be 350 feet, but well shielded by trees, from the 5,700-square-foot wooden chateau of David Long, the CEO of Liberty Mutual, the Boston-based insurance company. He calls the place “Summer Wind.’’

Long has hired a bunch of high-priced lawyers to try to kill the project through assorted technical arguments even as the Board of Selectmen and most others on the island support it. Long doesn’t want the peasantry near him.

Long may be typical of the imperial executives who have been running companies (and now the United States) since the ‘80s – obsessed with maximizing their personal wealth above all else and wallowing in conspicuous consumption. They tend to have houses in places such as the Hamptons and Nantucket which, since crowded by other rich people, further inflates their self-importance.

Long was paid about $20 million last year, and, as The Boston Globe famously noted, $4.5 million was spent to renovate his 1,335-square-foot office (throne room?) at Liberty Mutual.

Such folks are making Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard boring. They’re building a Greenwich, Conn., on sand dunes.

'Drifting on the breeze'

"The fragrant air is full of down,

Of floating, fleecy things

From some forgotten fairy town

Where all the folk wear wings.

Or else the snowflakes, soft arrayed

In dainty suits of lace,

Have ventured back in masquerade,

Spring's festival to grace.

Or these, perchance, are fleets of fluff,

Laden with rainbow seeds,

That count their cargo rich enough

Though all its wealth be weeds.

Or come they from the golden trees,

Where dancing blossoms were,

That now are drifting on the breeze,

Sweet ghosts of gossamer? ''

"The End of May,'' by Katherine Lee Bates, of Falmouth, Mass. She wrote the lyrics for "America the Beautiful''.

Nicholas Boke: Interactive climate simulation

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

MIT Prof. John Sterman recently visited Brown University to engage students and the public with interactive climate modeling. (Nicholas Boke/ecoRI News)

PROVIDENCE — “Climate is a complicated, noisy problem,” John Sterman told an audience of the climatologically inclined at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs on May 1.

“Climate change is real,” he continued. “The problem is that the costs are deferred to the future.”

But the worst part, he explained, is that as soon as any climate expert anywhere projects yet another graphic of the rise of atmospheric carbon dioxide onto a screen, then superimposes the parallel rise in the Earth’s temperature, “most talks on climate go off the rails.

“We start off saying, ‘Lemme tell you the facts,’ because we know that science needs to show the evidence, about which there’s no credible doubt any more. But the public’s not there yet. And we’ve got research that shows just providing information doesn’t work.”

At which point, Sterman projected a photo of an audience dozing contentedly through a presentation on climate change.

Sterman, an MIT professor of management, and his colleagues believe that they’ve found a way around this public-awareness Catch-22: an interactive online world climate simulation called the Climate Rapid Overview and Decision Support (C-ROADS), which allows visitors to see what happens to temperature increase, sea-level rise and related impacts when countries make various decisions about carbon dioxide emissions.

So twice Sterman took audiences through the C-ROADS process. The first time was during the hour he spent with the general public at an event sponsored by the Institute at Brown for Environment & Society. The second, a three-hour event, was with several dozen students in Eric Patashnick’s system dynamics class.

The principle is simple. Participants run three-dimensional climate models on their laptops, plugging in “decisions” and watching the impact on global temperature rise.

This interactive Web site is well beyond beta-testing. It’s been used by participants in the 2014 China-U.S. negotiations on climate change, at the 2016 Paris meeting at which the latest U.N. climate accords were agreed upon, and at more than 800 events in 76 countries involving more than 40,000 participants.

Participant then-Secretary of State John Kerry effused, “I have to tell you, it works … I used it,” and the Dalai Lama, who has also engaged in the process, promised, “I will join you, shouting!”

Explaining that “If [Secretary of State] Pompeo wants to get serious and fill the seat of the special envoy on climate change, I’ll run him through it,” Sterman said.

The process

At Brown University earlier this month, Sterman ran both groups through the process.

With the general audience he flashed the C-ROADS page on the screen. It offered graphs showing carbon dioxide emissions by group and temperature increase by year, 2000-2100. Below was a chart on which each group could project decisions they would make: the peak-emissions year, the year CO2 emissions would begin to decline and by what annual reduction rate, the amount of deforestation allowed, and the amount of “afforestation” — replacement of forests — that would be targeted.

When decisions made by each group — the United States, the European Union, China and developing nations — were entered into the system, the program would alter the slopes on the graphs and calculate the amount by which the currently projected 2100 temperature rise of 4.2 degrees Celsius (7.5 Fahrenheit) would be diminished.

“People say they don’t even know what they’re going to do after lunch,” Sterman said. “I ask if they have children, or if they might have children someday. So let’s figure out what you’re going to do after lunch, then figure out what to do about what really matters.”

With the hour-long general public group, he asked individuals to think like Putin or Trump or Xi Jinping, and to make decisions about each topic.

A woman — briefly thinking of herself as German Chancellor Angela Merkel — suggested that the European Union might be willing to cut emissions by 5 percent. Trump has agreed to 2 percent. Putin has said Russia would cut less than the United States. Xi Jinping said China would try for a 1 percent cut by 2035. India and Chile, of course, were reluctant to cut much, given their economic circumstances. The result, after further commitments, would be to bring the temperature rise from 4.2 degrees to 3 degrees.

“So the temperature keeps rising,” Sterman said, “because we’re still emitting and the concentration is still accumulating. It’s like pouring water into the tub at twice the rate it’s draining. We get ocean acidification, which affects the base of the food web, sea levels will rise by 1.8 meters [nearly 6 feet] and we’ll get more superstorms.”

Pictures of the projected impact of this level of sea-level rise on Shanghai and Bangladesh appeared, followed by a discussion of the social and political impacts of climate refugees.

Sterman flashed a picture of how much of Providence would be flooded with a 6-foot rise.

“Don’t think you’re safe at Brown,” he said. “The power plant is under water. At that level, what was once a hundred-year storm will take place every year.”

He and the audience went back and revised their figures, finally bringing the temperature rise down to 2.6 degrees Celsius.

“You can see what a game of Russian roulette this is we’re playing,” Sterman said. “You have to let people go through this process, not just tell them about it, if you want them to pay attention.”

Students give it a try

Later that afternoon, Sterman broke Patashnik’s class into groups of five or six, each of which were to play a role in the simulation: the United States, the European Union, other developed nations, China, India, other developing nations, the U.S. Climate Alliance (14 states and Puerto Rico), the fossil-fuel industry, and climate activists.

They were given a few minutes to plan their strategies, then sent out to negotiate with others.

The India delegation told the U.S. delegation that they couldn’t afford to cut much, but they’d participate more aggressively in the war on terror in exchange for big cuts by the United States and contributions to the global climate fund. The fossil-fuels group was willing to agree with China that reforestation was an effective tool. Africa and other developing nations didn’t feel they had much to bargain with.

The groups reported what they were willing to do, including how much money they would commit to support countries that needed help carrying out their commitments. Sterman entered their numbers into the C-ROADS program.

Once each group had entered its commitments, temperatures would rise by 3.1 degrees by 2100, resulting in a situation not unlike what the morning group had confronted.

“You’ll cross that two-degree threshold at 2050,” Sterman said, “when all of you are still alive and your children may be just about to enter college.”

He sent them back to renegotiate. The groups were eventually able to bring the temperature rise down to 2.3 Celsius by 2100, after China saw that it would lose Shanghai, the United States saw it would lose New Orleans, and that, as Sterman put it, “they realized that there’s no wall high enough to protect the developed world from the consequences.”

The Brown University students thought that the process was generally a productive one, though all acknowledged that real-world negotiations would be much more politically fraught than their efforts had been.

“It certainly put things into perspective,” Byron Lindo, a member of the developing nations group, said, “but everybody here already pretty much agrees about the problem.”

This online interactive program is open and free to all. Sterman said the program is appropriate for high school and up, for business leaders, government officials, and just plain folk.

Nicholas Boke is a freelance writer and international education consultant who lives in Providence.

Wait till you see the summer debris

"Winter Debris, Herring Cove, Provincetown,'' by Jane Paradise, in the show "The Tip: Images of the Outer Cape,'' with fellow photographer Dan Larkin at the Gallery UPSTAIRS, in Orleans, Mass., May 31-July 10.

David Warsh: The other Russia story

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It may seem like an odd time to bring up the other Russia story, this being the first anniversary of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s probe. But as it happens, there has been a break in this neglected case – or, rather, two of them.

It was slightly more than a year ago that President Trump fired FBI James Comey and, the next day, told Russian officials visiting the Oval Office that Comey was “crazy, a real nut job.” He continued, “I faced great pressure because of Russia. That’s taken off.” Two weeks later Mueller was appointed, and his Russia investigation has only escalated since then, sprawling into several unexpected corners.

The New York Times offered readers a helpful graphic last winter: “Most of the stories under the ‘Russia’ umbrella generally fall into one of three categories: Russian cyber attacks; links to Russian officials and intermediaries; alleged obstruction.”

There is, however, another aspect of the Russia story, a category altogether missing in the Times’ classification scheme, an obviously thorny topic that almost no one wants to discuss: the proverbial elephant in the room.

It concerns the extensive background to the 2016 campaign – the relationship between the United States and Russia over the long arc of the 20th Century, and, especially, the years since the end of the Cold War. This aspect is complicated, involving all five U.S. administrations since the Soviet Union dissolved itself at the end of 1991. It is a difficult story to tell.

I backed into it slowly, having followed for many years the Harvard-Russia scandal of the 1990s. In 1993, the U.S. Agency for International Development, a semi-independent unit of the State Department, hired Harvard University’s Institute for International Development to provide technical economic assistance to the Russian government on its market reforms. Eight years later, the Justice Department sued Harvard for having let its team leaders go rogue.

Harvard economist Andrei Shleifer and his deputy, Jonathan Hay, were accused of investing in Russian securities, and of having established their wives at the head the line in the nascent Russian mutual-fund industry. The suit was settled in 2005. The government recovered most of the money it had spent. The incident played a part in Harvard University president Lawrence Summers’s resignation the following winter. As Shleifer’s friend and mentor, Summers had distanced himself via recusal.

After Boris Yeltsin had died, in 2007, I wrote a column about the failures of U.S. policies in the 1990s. Thereafter I followed developments with increasing interest and alarm, particularly after the Ukraine crisis of 2014. And in the summer of 2016, when it seemed likely that Hillary Clinton would be elected president, I set out to collect some of the columns I had written and to add some additional narrative material in order to call attention to the entanglements she and her advisers would bring to the job. That project was supposed to take one year. It took two.

Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years (CreateSpace) was finally published on Amazon last week – 300 pages and a relative bargain at $15. The book consists of three main parts.

The first is a recap of the scandal as it appeared in the newspapers, from the front page of The Wall Street Journal, in August 1997; to Harvard’s decision, in March 2001, to try the case rather than settle the government suit; to September 2013, when Summers withdrew from the competition with Janet Yellen to head the Fed. These 29 columns, written as the story unfolded, introduce first-time readers to the scandal, and remind experts of what and when we knew and how we knew it.

The second part concerns the Portland, Maine, businessman whom the Harvard team leaders inveigled to start a mutual fund back-office firm in Russia, then forced out of its ownership. It turns out there was a second suit, overlooked for the most part because Harvard settled, paying an undisclosed sum in return for a non-disclosure agreement. This now-familiar tactic insured that John Keffer, whose Forum Financial at that point was one of the largest independently owned mutual fund administrators in the world, and a significant presence in Poland, would be unable to tell his story. Only his filings and the massive documentation of the government case remained.

The third consists of six short essays on aspects of the U.S. relationship with Russia since 1991. These relate a brief history of NATO expansion, which took place despite the administration of George H.W. Bush pledging in exchange for Russia agreeing to the reunification of Germany that the US would not further enlarge NATO; tell something of the U.S. press corps in Moscow during those 25 years; identify a key issue in Russian historiography; express some sympathy for ordinary Russians and even for Vladimir Putin himself; and seek to separate the accidental presidency of Donald Trump from all the rest, the better to understand why he has so little standing in in the matter.

Also included is a short paean to the news values of The Wall Street Journal and two appendices. One is Shleifer’s letter to Harvard provost Albert Carnesale as the USAID investigation built to its climax. The other is the heavily-annotated business plan, drafted by Hay’s then-girlfriend, Elizabeth Hebert, later his wife, to make it appear to have been written by Hay, and backed financially by Shleifer’s wife, hedge-fund proprietor Nancy Zimmerman, offering control of Keffer’s company to Thomas Steyer, of Farallon Capital (who had been Ms. Zimmerman’s principal original backer), and Peter Aldrich, of AEW Capital Management, a director of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Preparing to espouse these unpopular views has made me snap to attention on the rare occasions when they are expressed in the mainstream press – not on the op-ed pages, where they mostly represent reflexive ballast-balancing, but in the news pages, where some deeper form of institutional judgment is at work. That was the case last Sunday, when an 8,600-words article in the SundayNew York Times Magazine presented the case that the United States shared the blame for the current disorder. “The Quiet Americans” startled me (though not the designer, who illustrated it with a standard what-makes-Russia-tick? design). The dispatch itself was a significant advance in the other Russia story.

Keith Gessen, 53, is a Russian-born American novelist (A Terrible Country: A Novel) and journalist, a translator of Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich (Voices from Chernobyl). He is coeditor ofn+1, a magazine of literature, politics, and culture based in New York City as well\ and an assistant professor of journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He is a younger brother of Masha Gessen, 61, author of The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia(2017) and The Man without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin (2013); their parents emigrated, with four children, from the USSR to the US in 1981. (As an adult, Masha Gessen returned to Russia in 1991, leaving for a second time in 2013.)

In the article, Gessen writes that “behind the visible façade of changing presidents and changing policy statements and changing styles, [those who influenced U.S. policy toward Russia] were actually a small core of officials who not only executed policy but effectively determined it.” Getting out of the mess requires retracing the steps by which we got into it, he writes; that means starting with the small group of experts known as “the Russia hands.”

Gessen identifies and interviews many of the analysts who were in the vanguard of NATO expansion: Victoria Nuland, former NATO ambassador under Bush who became assistant secretary of state for Europe and Eurasia under President Obama; Daniel Fried, her predecessor under Bush; Stephen Sestanovich, ambassador to the Newly Independent States of the Former Soviet Union under President Clinton; Richard Kuglar, a strategist who co-wrote an influential 1994 RAND Corp. report advocating NATO expansion; and Strobe Talbott, deputy secretary of state for seven years under President Clinton, “the first-high level Russia hand of the post-Cold War.”

Interleaved with their stories are those of their critics, analysts “deeply skeptical of the missionary impulse that has characterized Ameican policy toward Russia for so long”:” Thomas Graham, of Kissinger Associates; Michael Kimmage, of the Catholic University of America; Olga Oliker, of the Institute for Strategic Studies;Michael Kofman, of the Wilson Center; Samuel Charap, of RAND Corp.; Timothy Colton, of Harvard University; Angela Stent, of Georgetown University; and the former Brookings Institution duo of Clifford Gaddy, of Pennsylvania State University, and Fiona Hill, now serving as an advisor to President Trump.

Conspicuously missing from Gessen’s account are veterans of the first Bush administration, Jack Matlock, ambassador to the USSR, in particular. Compensating for their absence are the anonymous quotations (in March) of a “senior official” of the Trump administration, “deeply knowledgeable and highly competent,'' which fits the description and the mindset of former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. For something of Gessen’s take on Putin, see his long article last year in The Guardian: Killer, kleptocrat, genius, spy: the many myths of Vladimir Putin,

Many of these names also appear in the second half of my book. The story is broadly the same: that bedizened by its “victory” in the Cold War, the United States has consistently overreached. But there is an important difference. Gessen concludes that the servants did it. I ascribe the blame mostly to the American presidents who hired the hands, to Bill Clinton in particular, who with his Oxford roommate Talbott and friend Richard Holbrooke began the process of NATO expansion over experts’ objections; George W. Bush, who continued and ramped it up with his “Freedom Agenda”; and Barack Obama, who may have been more concerned with the limits of American power than his first secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, but who continued the policies of his predecessors.

On the central point, however, Gessen and I completely agree. We both think the U.S. debate is seriously out of kilter. He quotes the legendary George Kennan, from his “Long Telegram” of 1946, which framed the long-term strategy of containment: “Much depends on the health and vigor of our own society.” Gessen then concludes:

"[American] society now looks sick. The absence of nuance on the Russia question – the embrace of Russia as America’s new-old supervillain – is probably best understood as a symptom of that sickness. And even as both parties gnash their teeth over Russia, politicians and experts alike seem to be in denial about mistakes made in the past and the lessons to be learned from them.''

He might also have mentioned the mainstream press: The Washington Post, the WSJ, the Times itself, at least until last week. That’s why I depend on Johnson’s Russia List for my coverage of the topics. For instance, I admire Bloomberg News columnist Leonid Bershidsky. I might not otherwise have seen his account of the “Who Lost Russia” debate last week between historian Stephen Cohen and former Obama Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul. Bershidsky is right when he states, “These days, Russia is merely a big football for Americans.” More revealing than the yardage between the opposing goalposts that are McFaul and Cohen is the scrimmage taking place somewhere in between, as, for instance, in the difference of opinion between Gessen and me. This other Russia story is just getting started.

David Warsh is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this first ran.

Chris Powell: Conn. doesn't need Indians to run its gambling; arrogant encounter at Yale

Foxwoods -- the Pequot tribe's gigantic casino and resort, in Ledyard, Conn.

Nobody calls for a special session of the Connecticut General Assembly when some financial scandal breaks in state government, as when, the other day, the state auditors reported that the state Department of Economic and Community Development, which gives tens of millions of dollars away every year, has never learned how to count money or jobs.

But last week, when the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated the federal law that prohibited states from authorizing sports betting, Gov. Dannel Malloy and state legislators quickly announced their interest in a special session to get state government into the sports betting business. The governor and legislators imagine annual sports betting tax revenue of as much as $80 million.

Just as Connecticut's authorization of Indian casinos 30 years ago pushed most of the rest of the country into casino gambling, the Supreme Court decision will push most states into sports betting, and much faster, since the Internet instantly will carry any state's sports betting nationwide. Connecticut and other states will either undertake their own sports betting or forfeit the sports betting of their residents to other states.

The sports betting issue facing Connecticut is simply whether state government will accept the claim of its two reconstituted Indian tribes that their casino duopoly arrangement with the state gives them exclusivity on sports betting as well. The claim hinges on whether sports betting is to be considered just as much a casino game as slot machines and blackjack.

So this is the moment for state government to assert its sovereignty, to reject the tribes' claims and start subjecting their casino exclusivity rights to regular auction. Those rights well may be worth more than what the tribes long have been paying -- 25 percent of their slot-machine revenue.

Connecticut doesn't need Indians to run its gambling. Anybody else might do it.

xxx

ARROGANCE AND CONCEIT AT YALE: Of course admission to Yale University is competitive, but even so the school seems to have more than its share of arrogant and conceited students.

Two of them made national news the other day when one, a white woman, discovered another, a black woman, napping in a dormitory lounge at night. Apparently assuming that the black woman was a hobo or something worse, the white woman told her she couldn't sleep there.

The black woman, who had been writing a paper, replied that she was a student. The white woman said she was calling the police anyway. The black woman told her to go ahead and recorded the exchange on her cellphone. The police came and determined nothing was wrong.

But the black woman couldn't leave it at that. She vented on the police her resentment of the white woman's presumption, telling the cops that her ancestors had built the university, apparently because its early benefactor, Elihu Yale, who in 1718 donated what today would be about $185,000, had been a slave trader -- as if in the three centuries since then no one else has built the university, too.

The university said it had admonished the white student. Then it sank into its usual squishy political correctness, declaring that it would commence "conversations" about "inclusiveness." Yale should have just told its students to take the chips off their snotty shoulders.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Meredith Angwin: New Englanders should get ready for rolling blackouts

Mystic Station power plant, in Everett, Mass., where two gas-fired units might be closed.

WILDER, Vt.

Rolling blackouts are probably coming to New England sooner than expected.

When there’s not enough supply of electricity to meet demand, an electric grid operator cuts power to one section of the grid to keep the rest of the grid from failing. After a while, the operator restores the power to the blacked-out area and moves the blackout on to another section. The New England grid operator (ISO-NE) recently completed a major study of various scenarios for the near-term future (2024-2025) of the grid, including the possibilities of rolling blackouts. (ISO stands for Independent System Operator.)

In New England, blackouts are expected to occur during the coldest weather, because that is when the grid is most stressed. Rolling blackouts add painful uncertainty – and danger – to everyday life. You aren’t likely to know when a blackout will happen, because most grid operators have a policy that announcing a blackout would attract crime to the area.

Exelon announces plan to close Mystic Station

In early April, Exelon said that it would close two large natural-gas-fired units at Mystic Station, in Everett, Mass. In its report about possibilities for the winter of 2024-25, ISO-NE had included the loss of these two plants as one of its scenarios. The ISO-NE report concluded that Mystic’s possible closure would lead to 20 to 50 hours of load shedding (rolling blackouts) and hundreds of hours of grid operation under emergency protocols.

When Exelon made its closure announcement, ISO-NE realized that the danger of rolling blackouts was suddenly more immediate than 2024. ISO-NE now hopes to grant “out of market cost recovery” (that is, subsidies) to persuade Exelon to keep the Mystic plants operating. If ISO-NE gets FERC permission for the subsidies, some of the threat of blackouts will retreat a few years into the future.

Winter scenarios and natural gas

The foremost challenge to grid reliability is the inability of power plants to get fuel in winter. So ISO-NE modeled various scenarios, such as winter-long outages at key energy facilities, and difficulty or ease of delivering Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) to existing plants.

Ominously, 19 of the 23 of the ISO-NE scenarios led to rolling blackouts. The worst scenarios, with the longest blackouts, included a long outage at a nuclear plant or a long-lasting failure of a gas pipeline compressor.

A major cause of these grid problems is that the New England grid is heavily dependent on natural gas. Power plants using natural gas supply about 50 percent of New England’s electricity on a year-round basis. Pipelines give priority to delivering gas for home heating over delivering gas to power plants. In the winter, some power plants cannot get enough gas to operate. Other fuels have to take up the slack. But coal and nuclear generators are retiring, and with them goes needed capacity. In general, the competing-for-natural-gas problem will get steadily worse over time.

All the ISO-NE scenarios assumed that no new oil, coal, or nuclear plants are built, some existing plants will close, and no new pipelines are constructed. Their scenarios included renewable buildouts, transmission line construction, increased delivery of LNG, plant outages and compressor outages.

Natural gas and LNG

The one “no-problem” scenario (no load shedding, no emergency procedures) is one where everything goes right. It assumed no major pipeline or power plant outages. It included a large renewable buildout plus greatly increased LNG delivery, despite difficult winter weather. This no-problem scenario also assumes a minimum number of retirements of coal, oil and nuclear plants.

This positive scenario is dependent on increased LNG deliveries from abroad. Thanks to the Jones Act, New England cannot obtain domestic LNG. There are no LNG carriers flying an American flag, and the Jones Act prevents foreign carriers from delivering American goods to American ports.

We can plan to import more electricity, but ISO-NE notes that such imports are also problematic. Canada has extreme winter weather (and curtails electricity exports) at the same time that New England has extreme weather and a stressed grid.

New England needs a diverse grid

To avoid blackouts, we need to diversify our energy supply beyond renewables and natural gas to have a grid that can reliably deliver power in all sorts of weather. When we close nuclear and coal plants and don’t build gas pipelines, we increase our weather-vulnerable dependency on imported LNG.

We need to keep existing nuclear, hydro, coal and oil plants available to meet peak demands, even if it takes subsidies. Coal is a problem fuel, but running a coal plant for a comparatively short time in bad weather is a better choice than rolling blackouts.

This can’t happen overnight. It has to be planned for. If we don’t diversify our electricity supply, we will have to get used to enduring rolling blackouts.

-----

Meredith Angwin is a retired physical chemist and a member of the ISO-NE consumer advisory group. She headed the Ethan Allen Institute’s Energy Education Project and her latest book is Campaigning for Clean Air.