'All things were glad'

“Spring flew swiftly by, and summer came; and if the village had been beautiful at first, it was now in the full glow and luxuriance of its richness. The great trees, which had looked shrunken and bare in the earlier months, had now burst into strong life and health; and stretching forth their green arms over the thirsty ground, converted open and naked spots into choice nooks, where was a deep and pleasant shade from which to look upon the wide prospect, steeped in sunshine, which lay stretched out beyond. The earth had donned her mantle of brightest green; and shed her richest perfumes abroad. It was the prime and vigour of the year; all things were glad and flourishing.”

-- Charles Dickens, from Oliver Twist.

Summers on Boston harbor and one in the newsroom

Ah, those usually boring summer jobs. From the time I was 13 to when I was 16 I had a series of the usual jobs --- mowing lawns, cutting shrubs, delivering papers vis bicycle, briefly busboying. But when I turned 16 I started working at a company on the Boston waterfront called Mills Transfer Co., which picked up stuff brought in by ship to the Port of Boston and trucked it around the Northeast.

Mostly what I did was utter tedium – filing multicolored bills of lading and, a bit better, making some deliveries around Boston. Occasional excitement was provided when the IBM punch-card machines malfunctioned, exploding those “do not fold or mutilate’’ cards all over the floor.

But the floor where I worked had a superb view of Boston Harbor and Logan Airport, and it was fun to be sent down to the loading dock to talk with the truckers. Best was that docked nearby by a lunch boat that my office mates (all of whom were full-time employees; I was the only summer worker) took a couple of times a summer around the inner part of Boston Harbor. The wind was soothing on those hot days, albeit often smelly. Boston Harbor was far more polluted than it is now.

Much of the waterfront then was still decrepit. Boston’s redevelopment took a while to get to the waterfront, and arson seemed to be the most common method of removing the eyesores of crumbling old building and collapsing piers. Still , there was a certain romance to it.

So through the hot and humid days of July and August I would trudge from South Station, where the bus from Cohasset, where I lived in the summer (I lived at school in Connecticut most of the rest of the year) stopped, to Mills Transfer, walking over the foul Fort Point Channel. At 5 p.m., I reversed the trip, noting that upon entering August, the light became noticeably dimmer. And then came the tedious traffic jams on the Southeast Expressway that often maderest of the trip home take more than an hour.

Still the boredom involved led me to become a loyal newspaper reader: There was nothing else to do.

So as the summer of 1969 approached and I was looking for a new kind of summer job, I lucked out when an AA friend of my mother, a natty sports columnist called Joe Purcell, helped get me a job as an “editorial assistant’’ (i.e., "copy boy'') at the Boston Record American, a Hearst tabloid heavy on murders and “The Daily Number.’’

The Record was in a beautiful granite building on Winthrop Square in downtown Boston. But other than the executive offices, the facility was not air-conditioned . The filthy newsroom was stifling. There were jars of salt tablets around to try to ward off collapse and a couple of weak fans.

I helped by cutting the teletype paper before handing wire-service copy to rewritemen (there was only one lady journalist in the room), made “books’’ – 2 carbon sheets sandwiched with three sheets of paper for writing stories, was given money by editors to give to the bookies in the composing room and was sent on rather pleasant errands around Boston. It was always cooler on the streets than in the newsroom. (The composing room and press room must have been close to 100 degrees.) For instance, I had to pick up stuff at the Boston Stock Exchange and the Associated Press.

It was the summer of “Woodstock’’ (which of course didn’t happen in Woodstock but rather in Bethel, N.Y.), the moon landing and Ted Kennedy’s Chappaquiddick scandal. The Record being only about an inch above a scandal sheet, the last story drew the most attention in the newsroom in the Capital of the Kennedys. I heard many salacious remarks, but don’t remember details all these years later.

-- Robert Whitcomb

Llewellyn King: The pernicious effects of polling on the body politic

Warning: the political news you are consuming may be synthetic, manufactured in a corporation and served up breathlessly by the media. Like many synthetic substances, it could be bad for your health.

I refer, of course, to the epidemic of polling. Polls have become a political narcotic. There is an appetite for them that knows no bounds. If you do not like or trust one poll, take another.

This, in turn, reflects a time when the science of polling faces challenges. Polling had become fearsomely accurate, but recently it has encountered two bugaboos: Changing demographics and changing telephone usage. These things have cleft polling in two: polls that are conducted through telephone interviews and those that are conducted electronically.

The evidence is that the old way remains more accurate, but it is bedeviled with fewer land lines and more people who do not want to be interviewed, or may not be comfortable speaking English.

It is, I am told, cheaper to poll electronically, but the bugs are not all out of the system and wide discrepancies in results are showing up. Hence, a poll that shows Hillary Clinton beating Donald Trump in the general election is followed by another equally reputable poll that shows Trump defeating Hillary.

The pollsters I have known are a canny lot, and I have no doubt they will get on top of these problems. The most egg that has landed on the face of the polling industry was in getting the last British election so wrong. That fiasco is informing the doubt surrounding polls on whether or not Britain should leave the European Union. They are struggling with a close call and public distrust of polling.

In the United States, polling has gotten the presidential primaries more or less right. But the putative contest between Clinton and Trump has wide swings in polling results; so wide that the pollsters themselves are having difficulty asking the right questions and managing the results.

Not since 1945, when it started seriously, has polling seemed so challenged as in this presidential contest.

But unreliable or not, the debate is fashioned by the polls. Talk radio, talk television and the newspapers are nourished by the latest polls, which pass as news.

For me the argument is not whether the polls are accurate, but rather the damage they do to the system. They are — and I am assuming that the pollsters will regain their former omnipotence — an impediment to the political process.

A poll is a snapshot that morphs into a narrative. A second in time becomes a reality, and candidacies are extinguished before they can catch fire.

Commentators extrapolate a grain of truth into a mountain of fact.

Polling has reached a point where not only is it part of the democratic process, but it also distorts that process, picking winners and losers before the electorate has assimilated the facts.

The news media has fallen onto the habit of taking this synthetic news — a suspect commodity for which the great news organizations pay — as the real thing. A poll gets the same weight as the ballot, thus affecting the ballot.

I believe that polls do reveal a truth, but a truth of one brief moment in time. The trouble is that revelation becomes the revealed truth, and the future gets tethered to that moment. Normal evolution in political thinking is hampered by this synthetic truth.

In hiring pollsters, news organizations are unwittingly setting up what is the equivalent of a posed photograph: a photograph that will be reprinted hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of times until it has become a kind of truth and its dubious genesis is forgotten.

Politicians are swayed by polls, fitting their policies to synthetic truths that have been certified as the will of the people: erroneous certifications, as it happens.

Llewellyn King is the host and executive producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and a longtime publisher, columnist and international business consultant. This piece first ran on Inside Sources.

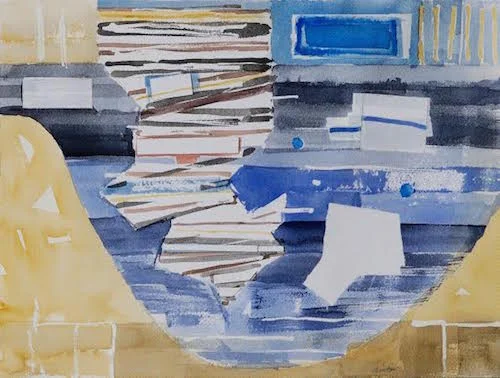

Or your office during an earthquake

"Pond With Flash'' (watercolor), by Milo Winter, at ArtProv Gallery, Providence, June 8-July 22.

William Morgan: Touring the treasures of a cold campus

Spring in northern New England is a sometime thing. It does not usually come until May, if at all, and it doesn’t stay very long. (There's a bit of Yankee humor: "Spring around here is short. Last year, we played baseball that afternoon''.) A recent visit to Maine reminded me that we were still very much in what the late Noel Perrin, my favorite Dartmouth professor, called one of New England's six seasons: "Unlocking''. Except for a few brave daffodils, there were no flowers to be seen and few leaves on the trees.

Waiting for spring: House neat Wiscasset, Maine.

My wife and I walked around Bowdoin College during this period of grayness. Where, we wondered, were the crowds of prospective Polar Bears touring the campus on their spring break? Our own son had seen the Brunswick school in the flush of summer. Would an introduction in November or March have chilled his ardor for Bowdoin? What about students from Virginia or California showing up expecting Maine to look as it appears in online college promotional material?

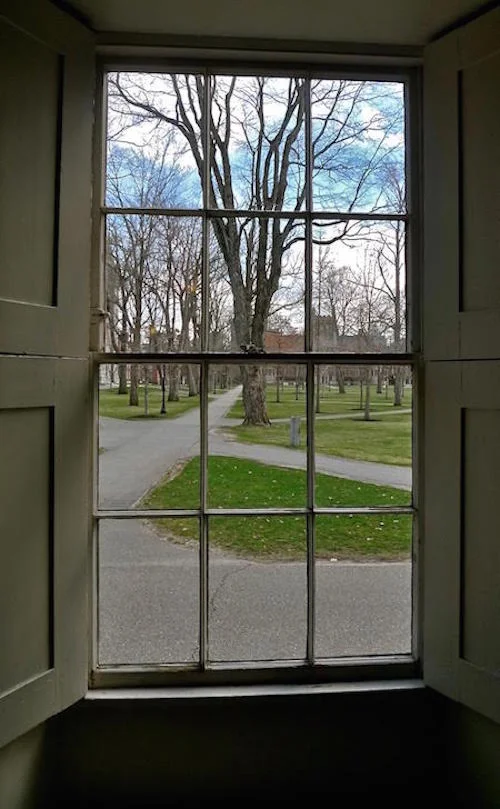

Main Green at Bowdoin College, looking north.

Yet, we found something strangely appealing about Bowdoin at this time of year–a kind of astringency, a stark honesty defined by barebones trees. There was a sense of what it means to live in Maine year round, or to have attended Bowdoin, say, back in the 1820s, along with Longfellow and Hawthorne, when Brunswick was far away and pretty isolated from the world.

View of the green from Massachusetts Hall (1802),Bowdoin's oldest building.

Minus the leafed-out of shrubbery and flowering trees, it is a lot easier to appreciate the astounding collection of notable 19th Century and early 20th Century architecture that forms the center of the Bowdoin campus.

Charles McKim, of McKim, Mead & White, was the most famous American architect to build at Bowdoin. The Walker Art Museum (1894) is a perfect Renaissance revival jewel. The Western canon of painters, sculptors and architects whose names are carved on the façade might now be seen as a group of dead white men, but it was a typical homage found on Beaux-Arts civic buildings

Richard Upjohn was another giant of American architecture, best known for his Gothic revival churches, such as Trinity Church on Wall Street in New York. Upjohn, however, employed his beloved English Gothic only for Episcopalians. So the Bowdoin Chapel, 1844-55, was built in a severe German Romanesque for the Maine Congregationalists–a commanding if stern house of worship.

The tall and narrow chapel, with its large murals and painted ceiling, is an unexpected change from the starkness of unadorned white interiors of the typical New England meetinghouse.

Although not as famous as either Upjohn or McKim, Boston architect Henry Vaughan was a major designer of churches and colleges. Like Upjohn, he championed English Gothic. Here, Searles Science Hall of 1894 is an early example of a Jacobean-inspired collegiate building in America.

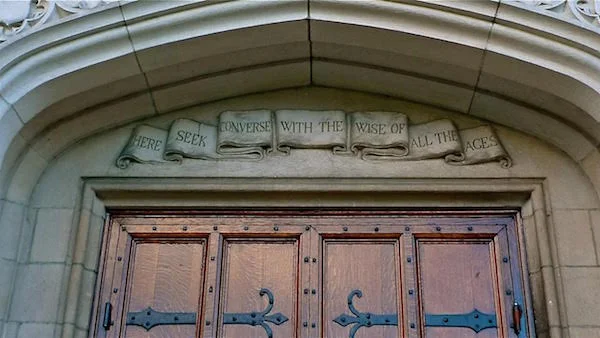

Echoes of Oxford and Cambridge, where Vaughan worked before emigrating to America, inform his Hubbard Library (1903). Soon, the lawn would be home to Frisbee games.

Above the entrance to Hubbard Library is this flowing banner carved with the admonition: Here Seek Converse With The Wise Of All Ages. Would such a motto be welcome in today's politically correct academy?

William Morgan is a longtime architectural historian and essayist. His books include Monadnock Summer: The Architectural Legacy of Dublin, New Hampshire and A Simpler Way of Life: Old Farmhouses of New York and New England

.

Still, rejoice

It was a splendid summer morning and it seemed as if nothing could go wrong.

-- John Cheever

Of course, plenty went wrong in the life of the great short-story writer and novelist Cheever, who grew up on Boston's South Shore. But he almost always found reasons for hope and redemption. The last line of his novel Falconer is "Rejoice''.

Jill Richardson: Blaming the poor for being poor

Via OtherWords.org

If you’re poor, many Americans think, it’s your own fault. It’s a sign of your own moral failing.

I don’t personally believe that, but the idea has roots in our culture going back centuries.

In The Wealth of Nations, the foundational work of modern capitalism, Adam Smith extolled the virtues of working hard and being thrifty with money. That wasn’t just the way to get rich, he reasoned — it was morally righteous.

Sociologist Max Weber took the idea further in describing what he called the Protestant work ethic.

To Puritans who believed that one was either predestined for heaven or for hell, Weber wrote, working hard and accumulating wealth was a sign of God’s blessing. Those who got rich, the Puritans thought, must have been chosen by God for heaven; those who were poor were damned.

Even major American philanthropists have subscribed to this idea.

John D. Rockefeller, a religious Baptist, thought that his vast wealth was evidence from God of his righteousness. Fortunately, he took this as a sign that he should use his money for good. He gave it to universities and medical research centers, and his descendants used it for great art museums, national parks, and more.

But Rockefeller also believed that the poor were often deserving of their fate. If they’d just worked harder, or budgeted their money wisely, then they wouldn’t be poor.

Plenty of Americans agree. Sadly, that’s often not the case.

The first factor determining one’s wealth as an adult is an accident of birth. If you’re born to wealthy parents, you’ll go to better schools and get better health care. Your odds of success as an adult are higher.

If, on other hand, you’re born to poor parents who must work multiple jobs instead of staying home to care for you — or who can’t afford healthy food, medical care, or a house in a good school district — your chances of earning your way into the middle class as an adult plummet.

In fact, if your parents’ income is in the bottom 20 percent, there’s you’ll be stuck in that low-income bracket for your entire life. Thanks to racism, that figure rises to 50 percent for black people born into poverty.

Indeed, racial disparities crop up even at the bottom of the ladder.

Due to historic racism and discrimination, data from the Economic Policy Institute shows, low-income white families tend to be wealthier than black families making the same income. Furthermore, whites are more likely to have friends and family who can help them out of a financial bind.

Finally, thanks to decades of discriminatory housing and lending practices, black families are more likely to live in poorer neighborhoods. That impacts the quality of the schools they attend, among many other things.

So why can’t a hardworking family get ahead? For one thing, it’s expensive to be poor.

Try finding an affordable place to live. You need to have enough cash on hand to pay a deposit. Many apartments require you to prove your income is 2.5 times the cost of the rent.

Public-assistance programs only help the most destitute, and often don’t provide enough even then.

For the disabled, the situation is worse. In theory, Social Security provides for those with disabilities. In reality, getting approved for disability payments is costly (in both medical and legal fees) and difficult. Once you get approved, disability payments are low, condemning you to poverty for life.

In short, there are many reasons why poor Americans are poor. It doesn’t help that our society thinks it’s their own fault.

Jill Richardson, an OtherWords.org columnist, is the author of Recipe for America: Why Our Food System Is Broken and What We Can Do to Fix It.

'For what they are'

By June our brook's run out of song and speed.

Sought for much after that, it will be found

Either to have gone groping underground

(And taken with it all the Hyla breed

That shouted in the mist a month ago,

Like ghost of sleigh-bells in a ghost of snow) --

Or flourished and come up in jewel-weed,

Weak foliage that is blown upon and bent

Even against the way its waters went.

Its bed is left a faded paper sheet

Of dead leaves stuck together by the heat --

A brook to no one but who remember long.

This as it will be seen is other far

Than with brooks taken otherwhere in song.

We love the things we love for what they are.

Robert Frost, ''Hyla Brook''

Inscrutable sculpture

“Pique with Citrine’’ (stone, shell, ceramic, metal, glass, plastic, paper clay), by Leslie Linda Brown, in her show "More Holes,'' at Kingston Gallery, Boston through May 29.

The gallery says that the title of exhibition refers to" the porous, eroded forms of the art; as the artist says, 'These works are half created and half destroyed.' Like unearthed, archaeological treasures, a key part of each sculpture's strength lies in its inscrutability. Ms. Brown's art possesses a wild elegance, where symmetry angles towards complexity at every turn, so that it is impossible to summarize the sculptures from a single point of view. The works comment on the current state of our environment, on the vital force of human connection, and on the potency of materiality in advancing emotional expression.''

Whew!

How Trump clawed up the towers of power

Watch and listen here to Libby Handros, the producer of Trump: What's the Deal?, talk on MSNBC about Mr. Trump's dubious rise to celebrity. A New York-based TV and film producer, she has been studying the real estate developer, "reality'' TV star and possible future president for decades. Then look at trumpthemovie.com

Lan Anh: Building a foundation for close U.S.-Vietnamese relations

By Lan Anh

On the night of May 22, President Obama landed at Noi Bai International Airport to start his official visit to Vietnam. U.S. Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush had also visited Vietnam while in office.

The American War in Vietnam was a long and sad chapter but that conflict ended 41 years ago.

President Obama’s visit to Vietnam was a dramatic turning point as the two countries establish stronger ties to promote the development, peace and security of the both countries, the Asia/Pacific region and the wider world.

Vietnam has spent much blood, wealth and time defending itself from invadersto regain and preserve its independence. The country has constantly faced threats to its freedom, sovereignty and territorial integrity.

But, overcoming the sorrow of historical events, and some missteps in its economic-development strategy, Vietnam has today achieved remarkable improvements in the economic and other aspects of its development. It has great potential strengths from its location and its population of 100 million, (making Vietnam the 13th most populous nation) including its large number of young people who are very receptive to new technology. It is also playing an increasingly important role in global economic development.

Meanwhile, Vietnam preserves many of its ancient traditions while it stays open to learning and accepting the best aspects of cultures and values all over the world.

Vietnam has become an inspiring story of a country in transition. A nation that suffered the sorrow of a long war with the U.S., Vietnam has since normalized the relationship with America and is taking steps to improve it further. Vietnamese-U.S. relations are now a world-recognized symbol of reconciliation and of progress toward a peaceful, more secure and developed world.

America has the world’s largest economy and is the global military superpower. Thus, the U.S. plays a crucial role in preserving stability around the Earth. American military power can be deployed quickly to any place in the world. Further, America is the innovation hub of the planet. It’s where leading technologies are constantly being invented and refined with great international impact.

Since World War II, the U.S. has led the establishment of a network of multilateral organizations -- most notably the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and such regional security organizations as NATO. In part becase of these organizations, the U.S. has strong allies around the world.

These factors are crucial parts of the foundation for stronger Vietnamese-U.S. relations.

Prof. Thomas Patterson, a leading Harvard scholar on politics, press and public policy, and a co-founder and director of The Boston Global Forum (BostonGlobalForum.org), said that the bases for a strong and sustainable relationship between the U.S. and Vietnam are trust and respect for each other and mutual understanding of each other’s needs and values. Despite some inevitable differences, the two countries have many shared goals, which include building their own and each other’s prosperity, friendly cultural exchanges and peace and security in the South China Sea (called in Vietnam the East Sea). Strong andfriendly U.S.-Vietnamese relations will foster the strong growth of the two countries in the Pacific Era.

The U.S. can help Vietnam with capital and advanced technology so that Vietnam can continue growing its knowledge and innovation economy via such technology solutions as artificial intelligence (AI) and network security.

After the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement (TTP) comes into effect, Vietnam’s GDP is projected to increase to $23.5 billion in 2020 and $33.5 billion in 2025. Its exports are projected to rise by $68 billion by 2026. Under the TPP, big markets, such as the U.S., Japan and Canada, willeliminate tariffs for goods imported from Vietnam, which will obviously give its exporting activity a big boost..

Meanwhile Fulbright University Vietnam has officially been granted approval to open. This is a milestone in the journey of cooperation between U.S. and Vietnam in education. Further, the University of California at Los Angeles ( UCLA ) will soon work with Vietnam to carry out new initiatives in global citizenship education.

To establish itself as a major global player, Vietnam needs to be independent of bigger countries so that it can strategize its path ahead while following universal standards and values. Vietnam will raise its visibility in the world with a loving, tolerant and generous attitude.

Vietnam has overcome sorrow and loss to make peace with other countries that caused it pain. Hence, Vietnam has become a symbol of reconciliation and can play an important role in preserving international peace and security in the Asia/Pacific region and around the world.

For example, Vietnam can contribute to the effort to resolve conflicts between the U.S. and Russia, between Europe and Russia, between China and Russia, between the U.S., Japan and North Korea, and between the U.S. and China. Vietnam could also become a centerfor finding solutions to conflicts in the Middle East and forhelping North Korea integrate with the rest of the world (as when Vietnam helped Myanmar reintegrate). And it can be a pioneer in building harmony and security in online space in South East Asia and around the world. This can include educating people to be responsible online citizens in Internet era; teaching them to respect each other’s culture, knowledge and morality, and promoting initiatives for global citizenship education.

Building strong Vietnamese-U.S. relations, as well as the other initiatives cited above, can’t be completed overnight but the path to a brighter future is opened. Tomorrow has started today.

Lan Anh is a journalist for VietNamNet.

Lyrical, tragic and comic

"Everything in nature is lyrical in its ideal essence, tragic in its fate, and comic in its existence."

-- George Santayana

Enough to make you jump

"Platform 1, Gorilla VI -- A Free and Anonymous Monument'' (C-type print on aluminum), by Jane and Louise Wilson, in the "Landscapes after Ruskin: Redefining the Sublime,'' curated by Joel Sternfeld and on view at the Hall Art Foundation, in Reading, Vt., through Nov. 27.

Dark thoughts in a black tie

We went to a black-tie fund-raising dinner for a nonprofit (Trinity Rep) last night in Newport. It may be my last after having attended dozens of these events over the years.

Yet again, I ask myself: Why not ditch these interminable, loud and often pompous affairs and just send money to these fine and always needy nonprofit outfits? (And I'm more conscious of the cost of going to these things these days because I no longer have a regular salaried job and because for 30 years I'd be, in effect, ordered to go to them by companies that employed me that would usually pay my tab. Corporate PR.)

Last night was the usual claustrophobic march from cocktails to the much too long general remarks and then the introductions of the prize winners of the night, in this case of some Pell Awards for the Arts. The introducers, as typical at these things, talked too much about themselves as we sat in folding chairs in a wind-battered tent. But a couple of the prize winners (whom I think might consider us semi-personal friends -- why we attended) were admirably concise in their acceptance remarks.

I was again surprised by the four-letter words and other reflections of the growing crudeness of our society in the remarks of some of the speakers. Depressing. But seeing how much some people had aged since I last saw them elicited my zoological interest. It recalled Proust's description of the old men and women in the last part of In Search of Lost Time whom he had known when they were young and fresh.

Then we went to the usual skimpy catered meal, in which the (very cheery) waiters seem to have been rigorously instructed to give diners the very minimum amount of wine. And then we were one night older....

-- Robert Whitcomb

Flash of beauty before the decline

Photo by Thomas Hook, who writes that this is "our first Swallowtail of the season, wings intact and not yet marred and chewed up by aging in this perilous world.''

Mr. Hook, a superb wildlife photographer based in Southbury, Conn., is an old friend and classmate. At our school reunion the other day we heard and saw many things to remind us of the ravages of time, amidst the lushness of May in Connecticut.

-- Robert Whitcomb

Young to old without transition

I went to a 50th boarding school reunion this past week in Connecticut and had several Proustian experiences. One of them was seeing the face of an old lady whom I well remembered as the lovely young wife of a faculty member. She is now a lovely old woman. Seeing her gave me a start, adding to the eerie quality of the reunion.

I hadn't see her for 50 years and so of course my brain had not had the opportunity to very slowly view -- and thus mostly ignore -- her aging

--- Robert Whitcomb

Frank Carini: Answers to global-warming deniers and minimizers

Well-documented facts, and common sense, tell us how humans are affecting the world, often with negative consequences. For example, greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, which we generate in abundance, are altering the climate, changing ocean chemistry and helping the seas rise.

Since ecoRI News first went online, in September 2009, people skeptical of manmade global warming — also referred to as climate change — have asked and e-mailed us, in most cases politely, to prove what most climate scientists already have. The following are the three most popular questions, presented in various forms, we have been asked in the past six-plus years:

Melting glaciers are often cited as proof of climate change. Given that they have been retreating for thousands years, why is their continued withdrawal, or even disappearance, of concern?

The obvious answer, at least to us, is that humans have built a lot of stuff, much of it highly valued, along the shore. In Newport, R.I., for instance, 968 historic structures are threatened by rising seas.

Whether you want to believe that belching smokestacks and tailpipes, deforestation and industrial agriculture, among many other human practices, have played a role in altering the planet’s climate, the fact is the world’s oceans have risen by an average of nearly 8 inches since the beginning of the 20th Century. They are projected to rise another 3-7 feet by 2100.

Even if you believe that Earth’s rising waters are part of a natural cycle, or your god’s will, the fact we have replaced natural coastal buffers, such as salt marshes and wetlands, with homes, roads, restaurants and tourist attractions has made our developed shorelines vulnerable to storm surge, flooding and erosion.

Now, southern New England’s coast is rebuilding itself, and humans weren’t invited to submit plans.

Besides contributing to global sea-level rise, fresh water from melting glaciers alters the sea, pushing down heavier salt water and changing ocean currents. The impacts ripple far and wide. Weather patterns change. Fish migrations change. Species go extinct. Temperatures rise, because the white surfaces of glaciers — they cover 10 percent of the Earth’s land — reflect the sun’s rays, helping to maintain the climate humans have become so accustomed to.

If even climate scientists are wrong — although my money’s on the science — lessening our dependence on the burning of fossil fuels would still improve public health and the environment’s well-being. No one would get hurt or suffer. A reconfigured energy industry would still provide plenty of employment opportunities. Plus, I’m sure the new-look industry could also be rigged to benefit the few over the many.

Of course, if the deniers are wrong, and we do nothing or not enough, it will prove costly on so many levels.

Environmentalists treat ecosystems as if they never change, attempting to preserve the same environment with which they grew up or trying to restore their vision of what the environment may have been like prior to industrialization and large-scale agriculture. But don’t ecosystems change all the time?

The often-used argument that the environment-was-going-to-change-naturally-and-species-were-going-to-go-extinct-regardless rings oh so hollow — kind of like a murderer defending himself by saying his victim was going to die eventually anyway.

Just because ecosystems change and species disappear without the help of human hands, doesn’t mean we have carte blanche to ruin environments for profit and sport. We share this sphere with many living things, and we have an obligation to future generations.

I, for one, would have enjoyed seeing a flight of passenger pigeons darken an afternoon sky. Sadly, the last one of its kind died in a zoo in 1914. We hunted them to extinction. Let’s hope we don’t make the same mistake with grizzly bears, wolves and African elephants.

The climate has changed many times in the past, so why is it a problem now?

The climate reacts to whatever forces it to change, and 7-plus billion humans — a population that is growing rapidly — are now the dominant force. It’s really no different than how an overpopulation of deer would stress a forest ecosystem. Neither species seems to be able to confront this reality.

Humans are stressing the plant’s resources through a combination of manmade pollution and ceaseless development. The negative impacts of our growth far outweigh the positives. Mother Nature will respond in kind. Why do you think we're looking to colonize Mars?

Frank Carini is the editor of ecoRI News.

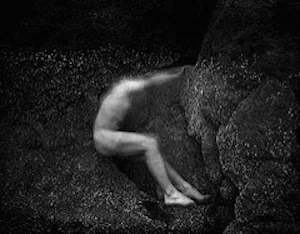

Naked in nature

From "What Grows Without,'' a show of photos by Chris Maliga, at Piano Craft Gallery, Boston, through May 29.

The show features black and white photos that deal with "the concept of oneself within nature as well as one's own identity,'' says the gallery. The photos show Mr. Maliga "alone and naked within different natural landscapes, speaking to his own personal struggle and experience.''

Llewellyn Smith: Hedrick Smith a torchbearer for beaten-down middle class

The middle class has been taking a shellacking for years. It began in the 1970s, when the business and political elites separated from the people and it has been accelerating ever since, according to Hedrick Smith, a former Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times reporter and editor, an Emmy award-winning PBS producer and correspondent, and a bestselling author. In short, an establishment figure.

Add to Smith’s establishment credentials schooling at Choate, the private boarding school, a stint at Oxford, and you have the picture of someone with the credentials to join the elite of his choosing. Instead Smith is a one-man think tank, a persuasive voice against the manipulation of the public institutions, such as Congress, for money and power.

But Smith is not a polemicist. He uses the reporter's tools, honed over decades in Moscow and Washington and on big stories, such as the civil-rights movement and the fall of the Soviet Union, to make his points against the assault on the middle class.

It all began with Smith's looking into what was happening to American manufacturing, which led to his explosive 2012 book, Who Stole the American Dream? Encouraged by the book's success, he created a Web site,reclaimtheamericandream.org, which now has a substantial following. In the past three years, he has lectured at over 50 universities and other platforms on his big issue: the abandonment of the middle class by corporate America and its corrupted political allies.

Smith documents the end of the implicit contract with workers, where they shared in corporate growth and stability. He outlines how money has vanquished the political voice of the middle class.

Instead, according to Smith, corporations have knelt before the false god of “shareholder value.” This has resulted in the flight of corporate headquarters to tax-friendlier climes, jobs to cheap labor, and a managerial elite indifferent to those who built the companies they manage.

In Smith’s well-researched world it is not only the corporations that have abandoned the workers, but the political establishment is also guilty, bowing to lobbyists and fixing elections through redistricting. Two big villains here: money in politics and gerrymandering electoral districts.

The result is a democracy in name only that serves the powerful and perpetuates the power of those who have stolen the system from the voters.

Smith cites the dismal situation in North Carolina, where districts have been drawn ostensibly to ensure black representation in Congress, but also to ensure Republican domination of all the surrounding districts. The two districts that illustrate the mischief are called “the Octopus” and “the Serpent” because of the way they are drawn to identify the voter preference of the inhabitants.

The rise of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump are testament to the broken system, says Smith. They are symbolic of the rising up of the middle class against the predations of the elites.

But Smith is hopeful because, he says, the states have taken up arms against the Washington and Wall Street elites. People should “look at the maps,” he says, “They will be surprised to find out that 25 states are engaged in a battle against partisan gerrymandering, or that 700 cities and communities plus 16 states are on record in favor of rolling back ‘Citizens United’ and restoring the power of Congress to regulate campaign funding.”

Smith sees the middle class reclaiming America: a great social revolution that again unites the government with governed, the creators of wealth with the managers of the wealth. Smith is no Man of La Mancha, tilting at windmills, but a torchbearer for a revolution that is underway and overdue.

“My thought is that more people would be emboldened to engage in grassroots civic action if they could just see what other people have already achieved,” he told me.

Smith’s Web site has drawn 82,000 visitors in the past year, and Facebook posts have reached 2.45 million, he says.

Smith cautioned me to write about the Web site and cause and not the man. But the man is unavoidable, and unique. He has as much energy as he had when I first met him in passing in a corridor at the National Press Club in Washington decades ago. At 82, Smith still plays tennis, skis, hikes, swims and dances with his wife, Susan, whom he describes as a “gorgeous dancer.”

At 6 feet 2 1/2 inches, Smith is an imposing figure at the lectern, but his delivery is gentle and collegiate: a reporter astounded and pleased with what he has found in the course of his investigation of the American body politic.

Llewellyn King is host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He is a long-time publisher, columnist and internationalist business consultant. This piece first ran on Inside Sources.