William Morgan: Haunting Stories from Cemetery in Bucolic Connecticut town

Scotland, a small town in northeastern Connecticut, was terra incognita until my wife, Carolyn, and I discovered it on a recent Sunday drive. Perhaps not the Edenic remembrance of first settler Isaac Magoon’s native Caledonia, but some time spent in the Windham County farming community revealed a modest treasure.

Set amongst some of the most bucolic topography of New England, with rolling hills, working farms, and an exceptional array of Cape Cod cottages, as well as Colonial and Greek Revival domestic architecture. The highlight of this gentle landscape was the steep hillside burial ground that contains two centuries of the town’s dead.

Old Scotland Cemetery North on Devotion Road. (There is a newer cemetery half a mile south.)

One stone from the late 18th Century is identified as a cenotaph, that is, a marker for someone who’s body is buried elsewhere, in the this case, the Caribbean Island of St. Lucia. Scotland may have been isolated, but it was not provincial. There are three standard Civil War graves stones, but surely these, too, lack the physical remains of the young men they memorialize.

During the first half of 1862, Union General (and Rhode Islander) Ambrose Burnside, employing New England regiments, tried to shut down Confederate blockade-running operations along the Outer Banks. Amos Weaver was presumably wounded in the Battle for Roanoke Island, dying of his wounds five days later.

The government-issue marble stones are the exception in Old Scotland. Most of the dead here lie beneath sandstone, a rarity when one recalls the typical slate steles of 18th-Century New England. Scotland had more than one artisanal stone carver. Joseph Manning and his sons Rockwell and Frederick contributed tombstones to the area for over six decades. It was John Walden, however, who provided Scotland with unique round faces.

Thomas, aged 1 year and 8 months, Anne lived but 2 hours, and Eunice expired at less than 3 months, 1795-99.

“Those little wondrous miniatures of man.

Form’d by unerring wisdom of perfect plan.

Those little strangers from eternal night.

Emerging from life’s immortal light.”

Mother of Thomas, Anna, and Eunice, 1805. Walden’s signature circular visage is almost subsumed by a weeping tree, and illuminated by a ghost-like lamp. Note the stylized wings of the departed.

“Mrs Bethiah, Consort to Capt Saml Morgan. Departed this Life Feb. 2d 1800, in the 61st Year of her age.

Left numerous offspring to Lament their loss.” Walden’s angel wings roll around the semicircle as decorative curtains.

Lydia Ripley was 79 when she departed this life in 1784. Primitive, unsophisticated, but powerful.

Providence-based writer and photographer William Morgan has written extensively about New England architecture and other art, townscape and landscape. His latest book is The Cape Cod Cottage (Abbeville Press).

Old Scotland Cemetery North

Scotland, a small town in northeastern Connecticut was terra incognita until Carolyn and

I discovered it on a recent Sunday drive. Perhaps not the Edenic remembrance of first settler

Isaac Magoon’s native Caledonia, but some time spent in the Windham County farming

community revealed a modest treasure. Set amongst some of the most bucolic topography of

New England, with rolling hills, working farms, and an exceptional array of Cape Cod cottages,

as well as Colonial and Greek Revival domestic architecture. The highlight of this gentle

landscape was the steep hillside burial ground that contains two centuries of the town’s dead.

Old Scotland Cemetery North on Devotion Road. (There is a newer cemetery half a mile south.)

One stone from the late 18 th century is identified as a cenotaph, that is, a marker for

someone who’s body is buried elsewhere, in the this case, the Caribbean Island of St. Lucia.

Scotland may have been isolated, but it was not provincial. There are three standard Civil War

graves stones, but surely these, too, lack the physical remains of the young men they

memorialize.

During the first half of 1862, Union General (and Rhode Islander) Ambrose Burnside, employing New England regiments,

attempted to shut down blockade-running operations along the Outer Banks. Amos Weaver was

presumably wounded in the Battle for Roanoke Island, dying of his wounds five days later.England regiments,

attempted to shut down blockade-running operations along the Outer Banks. Amos Weaver was

presumably wounded in the Battle for Roanoke Island, dying of his wounds five days later.

The government-issue marble stones are the exception in Old Scotland. Most of the dead

here lie beneath sandstone, a rarity when one recalls the typical slate steles of 18 th -century New

England. Scotland had more than one artisanal stone carver. Joseph Manning and his sons

Rockwell and Frederick contributed tombstones to the area for over six decades. It was John

Walden, however, who provided Scotland with unique round faces.

Thomas, aged 1 year and 8 months, Anne lived but 2 hours, and Eunice expired at less than 3 months,

1795-99.

Those little wondrous miniatures of man.

Form’d by unerring wisdom of perfect plan.

Those little strangers from eternal night.

Emerging from life’s immortal light.

Mother of Thomas, Anna, and Eunice, 1805. Walden’s signature circular visage is almost subsumed by a

weeping tree,

illuminated by a ghost-liked lamp. Note the stylized wings of the departed.

“Mrs Bethiah, Consort to Capt Saml Morgan. Departed this Life Feb. 2d 1800, in the 61 st Year of

her age.

Left numerous offspring to Lament their loss.” Walden’s angel wings roll around the semicircle as

decorative curtains.

Lydia Ripley was 79 when she departed this life in 1784. Primitive, unsophisticated, but

powerful.

Providence-based writer and photographer, William Morgan, has written extensively about New

England architecture and art, townscape and landscape. His latest book is The Cape Cod Cottage

‘Quiet disruption’

“Peace Offering III’’ (mixed fabricated and foraged materials on canvas), by Luanne E. Witkowski, in her show “Quiet Disruption,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, June 1-30.

She says:

“This is my peace offering, a quiet distraction, amidst the constant noise and chaos…

“There is so much beauty in this world that these works invite us all to live and fight for. My work combines my love for nature’s endless transitions and transformations, of changing color, temperature, drama with the practice of being in the studio with my assorted materials and wild foraged collections.’’

“It is a message of quiet disruption; a respite amidst the whirling storm raging all around that remembers ‘I am here.”’

Michael Anteby: In praise of Bureaucracy

Michel Anteby is a professor of management and organizations and sociology at Questrom School of Business & College of Arts and Sciences at Boston University.

Michel Anteby was during a decade a member of the Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth and a former Vice-Chair, and then Chair of the Commission.

From The Conversation (except for image above)

BOSTON

It’s telling that U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration wants to fire bureaucrats. In its view, bureaucrats stand for everything that’s wrong with the United States: overregulation, inefficiency and even the nation’s deficit, since they draw salaries from taxpayers.

But bureaucrats have historically stood for something else entirely. As the sociologist Max Weber argued in his 1921 classic “Economy and Society,” bureaucrats represent a set of critical ideals: upholding expert knowledge, promoting equal treatment and serving others. While they may not live up to those ideals everywhere and every day, the description does ring largely true in democratic societies.

I know this firsthand, because as a sociologist of work I’ve studied federal, state and local bureaucrats for more than two decades. I’ve watched them oversee the handling of human remains, screen travelers for security threats as well as promote primary and secondary education. And over and over again, I’ve seen bureaucrats stand for Weber’s ideals while conducting their often-hidden work.

Bureaucrats as experts and equalizers

Weber defined bureaucrats as people who work within systems governed by rules and procedures aimed at rational action. He emphasized bureaucrats’ reliance on expert training, noting: “The choice is only that between ‘bureaucratisation’ and ‘dilettantism.’” The choice between a bureaucrat and a dilettante to run an army − in his days, like in ours − seems like an obvious one. Weber saw that bureaucrats’ strength lies in their mastery of specialized knowledge.

I couldn’t agree more. When I studied the procurement of whole body donations for medical research, for example, the state bureaucrats I spoke with were among the most knowledgeable professionals I encountered. Whether directors of anatomical services or chief medical examiners, they knew precisely how to properly secure, handle and transfer human cadavers so physicians could get trained. I felt greatly reassured that they were overseeing the donated bodies of loved ones.

The sociologist Max Weber, pictured here circa 1917, wrote extensively about bureaucracy. Archiv Gerstenberg/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Weber also described bureaucrats as people who don’t make decisions based on favors. In other forms of rule, he noted, “the ruler is free to grant or withhold clemency” based on “personal preference,” but in bureaucracies, decisions are reached impersonally. By “impersonal,” Weber meant “without hatred or passion” and without “love and enthusiasm.” Put otherwise, the bureaucrats fulfill their work without regard to the person: “Everyone is treated with formal equality.”

The federal Transportation Security Administration officers who perform their duties to ensure that we all travel safely epitomize this ideal. While interviewing and observing them, I felt grateful to see them not speculate about loving or hating anyone but treating all travelers as potential threats. The standard operating procedures they followed often proved tedious, but they were applied across the board. Doing any favors here would create immense security risks, as the recent Netflix action film “Carry-On” − about an officer blackmailed into allowing a terrorist to board a plane − illustrates.

Advancing the public’s interests

Finally, Weber highlighted bureaucrats’ commitment to serving the public. He stressed their tendency to act “in the interests of the welfare of those subjects over whom they rule.” Bureaucrats’ expertise and adherence to impersonal rules are meant to advance the common interest: for young and old, rural and urban dwellers alike, and many more.

The state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education staff that I partnered with for years at the Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth exemplified this ethic. They always impressed me by the huge sense of responsibility they felt toward all state residents. Even when local resources varied, they worked to ensure that all young people in the state − regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity − could thrive. Based on my personal experience, while they didn’t always get everything right, they were consistently committed to serving others.

Today, bureaucrats are often framed by the administration and its supporters as the root of all problems. Yet if Weber’s insights and my observations are any guide, bureaucrats are also the safeguards that stand between the public and dilettantism, favoritism and selfishness. The overwhelming majority of bureaucrats whom I have studied and worked with deeply care about upholding expertise, treating everyone equally and ensuring the welfare of all.

Yes, bureaucrats can slow things down and seem inefficient or costly at times. Sure, they can also be co-opted by totalitarian regimes and end up complicit in unimaginable tragedies. But with the right accountability mechanisms, democratic control and sufficient resources for them to perform their tasks, bureaucrats typically uphold critical ideals.

In an era of growing hostility, it’s key to remember what bureaucrats have long stood for − and, let’s hope, still do.

Paula Span: When they don’t recognize you Anymore

—Photo by Diego Grez Cañete

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (except for image above)

It happened more than a decade ago, but the moment remains with her.

Sara Stewart was talking at the dining room table with her mother, Barbara Cole, 86 at the time, in Bar Harbor, Maine. Stewart, then 59, a lawyer, was making one of her extended visits from out of state.

Two or three years earlier, Cole had begun showing troubling signs of dementia, probably from a series of small strokes. “I didn’t want to yank her out of her home,” Stewart said.

So with a squadron of helpers — a housekeeper, regular family visitors, a watchful neighbor, and a meal delivery service — Cole remained in the house she and her late husband had built 30-odd years earlier.

She was managing, and she usually seemed cheerful and chatty. But this conversation in 2014 took a different turn.

“She said to me: ‘Now, where is it we know each other from? Was it from school?’” her daughter and firstborn recalled. “I felt like I’d been kicked.”

Stewart remembers thinking, “In the natural course of things, you were supposed to die before me. But you were never supposed to forget who I am.” Later, alone, she wept.

People with advancing dementia do regularly fail to recognize beloved spouses, partners, children, and siblings. By the time Stewart and her youngest brother moved Cole into a memory-care facility a year later, she had almost completely lost the ability to remember their names or their relationship to her.

“It’s pretty universal at the later stages” of the disease, said Alison Lynn, director of social work at the Penn Memory Center, who has led support groups for dementia caregivers for a decade.

She has heard many variations of this account, a moment described with grief, anger, frustration, relief, or some combination thereof.

These caregivers “see a lot of losses, reverse milestones, and this is one of those benchmarks, a fundamental shift” in a close relationship, she said. “It can throw people into an existential crisis.”

It’s hard to determine what people with dementia — a category that includes Alzheimer’s disease and many other cognitive disorders — know or feel. “We don’t have a way of asking the person or looking at an MRI,” Lynn noted. “It’s all deductive.”

But researchers are starting to investigate how family members respond when a loved one no longer appears to know them. A qualitative study recently published in the journal Dementia analyzed in-depth interviews with adult children caring for mothers with dementia who, at least once, did not recognize them.

“It’s very destabilizing,” said Kristie Wood, a clinical research psychologist at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and co-author of the study. “Recognition affirms identity, and when it’s gone, people feel like they’ve lost part of themselves.”

Although they understood that nonrecognition was not rejection but a symptom of their mothers’ disease, she added, some adult children nevertheless blamed themselves.

“They questioned their role. ‘Was I not important enough to remember?’” Wood said. They might withdraw or visit less often.

Pauline Boss, the family therapist who developed the theory of “ambiguous loss” decades ago, points out that it can involve physical absence — as when a soldier is missing in action — or psychological absence, including nonrecognition because of dementia.

Society has no way to acknowledge the transition when “a person is physically present but psychologically absent,” Boss said. There is “no death certificate, no ritual where friends and neighbors come sit with you and comfort you.”

“People feel guilty if they grieve for someone who’s still alive,” she continued. “But while it’s not the same as a verified death, it is a real loss and it just keeps coming.”

Nonrecognition takes different forms. Some relatives report that while a loved one with dementia can no longer retrieve a name or an exact relationship, they still seem happy to see them.

“She stopped knowing who I was in the narrative sense, that I was her daughter Janet,” Janet Keller, 69, an actress in Port Townsend, Washington, said in an email about her late mother, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. “But she always knew that I was someone she liked and wanted to laugh with and hold hands with.”

It comforts caregivers to still feel a sense of connection. But one of the respondents in the dementia study reported that her mother felt like a stranger and that the relationship no longer provided any emotional reward.

“I might as well be visiting the mailman,” she told the interviewer.

Larry Levine, 67, a retired health-care administrator in Rockville, Maryland, watched his husband’s ability to recognize him shift unpredictably.

He and Arthur Windreich, a couple for 43 years, had married when Washington, D.C., legalized same-sex marriage in 2010. The following year, Windreich received a diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Levine became his caregiver until his death, at 70, in late 2023.

“His condition sort of zigzagged,” Levine said. Windreich had moved into a memory-care unit. “One day, he’d call me ‘the nice man who comes to visit’,” Levine said. “The next day he’d call me by name.”

Even in his final years when, like many dementia patients, Windreich became largely nonverbal, “there was some acknowledgment,” his husband said. “Sometimes you could see it in his eyes, this sparkle instead of the blank expression he usually wore.”

At other times, however, “there was no affect at all.” Levine often left the facility in tears.

He sought help from his therapist and his sisters, and recently joined a support group for LGBTQ+ dementia caregivers even though his husband has died. Support groups, in person or online, “are medicine for the caregiver,” Boss said. “It’s important not to stay isolated.”

Lynn encourages participants in her groups to also find personal rituals to mark the loss of recognition and other reverse milestones. “Maybe they light a candle. Maybe they say a prayer,” she said.

Someone who would sit shiva, part of the Jewish mourning ritual, might gather a small group of friends or family to reminisce and share stories, even though the loved one with dementia hasn’t died.

“To have someone else participate can be very validating,” Lynn said. “It says, ‘I see the pain you’re going through.’”

Once in a while, the fog of dementia seems to lift briefly.

Researchers at Penn and elsewhere have pointed to a startling phenomenon called “paradoxical lucidity.”

Someone with severe dementia, after being noncommunicative for months or years, suddenly regains alertness and may come up with a name, say a few appropriate words, crack a joke, make eye contact, or sing along with a radio.

Though common, these episodes generally last only seconds and don’t mark a real change in the person’s decline. Efforts to recreate the experiences tend to fail.

“It’s a blip,” Lynn said. But caregivers often respond with shock and joy; some interpret the episode as evidence that despite deepening dementia, they are not truly forgotten.

Stewart encountered such a blip a few months before her mother died. She was in her mother’s apartment when a nurse asked her to come down the hall.

“As I left the room, my mother called out my name,” she said. Though Cole usually seemed pleased to see her, “she hadn’t used my name for as long as I could remember.”

It didn’t happen again, but that didn’t matter. “It was wonderful,” Stewart said.

Paula Span is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter.

Chris Powell: Trump isn’t what’s wrong with Conn. public education

1839 caricature by George Cruikshank of a school flogging.

The Hartford High School building constructed in the early 1880’s and, sadly, demolished in the 1960’s. (This is a 1911 postcard.) Public secondary education in Hartford started in 1638, the second-oldest equivalent of a high school in America. The first is the Boston Latin School, founded in 1635.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont and state Education Commissioner Charlene Russell-Tucker are being cheered for refusing to certify to the U.S. Education Department that state government is in compliance with the Trump administration's view of civil-rights law. The administration's view is that ‘‘diversity, equity, and inclusion," the slogan of what I see as leftist education, is unconstitutional because it means that government is enforcing racial preferences in schools.

Exactly what racial preferences are Connecticut's schools enforcing? The Trump administration's letter to the state Education Department didn't say. The Education Department's reply said the state, with its "diversity, equity, and inclusion," is following federal law. So now, for not nodding politely at the Trump administration, Connecticut is at risk of losing millions of dollars in federal education grants, and millions may be spent in litigation to determine what, if anything, it all means.

The governor and education commissioner should have provided the certification the Trump administration sought and left it to the administration to cite specific reasons for canceling grants to the state. But no -- the governor, the commissioner, and Democratic state legislators want to be seen fighting Trump and to look like they're standing up for education.

The governor grandly proclaimed: “In Connecticut we're proud to support the incredible diversity of our schools and work tirelessly to ensure that every child, regardless of background, has access to a quality education and the best opportunity at the starting line in life. From our educators, who are mentoring and inspiring the next generation of young people, to our curriculum, our commitment to education is what has made our schools nationally recognized, and we plan to continue doing what makes our students, teachers, and schools successful."

Oh, really?

It's not because of Trump that, despite all that “diversity, equity, and inclusion," Connecticut's schools are still heavily segregated racially.

It's not because of Trump that Connecticut's schools long have had a mortifying racial performance gap.

It's not because of Trump that, according to the little standardized testing state government dares to permit, student proficiency has been declining for decades even as per-pupil spending has risen sharply.

It's not because of Trump that Connecticut legislators and educators have decided opportunistically to pretend that more spending equals more education even as decades of test results contradict them.

It's not because of Trump that Hartford's and Bridgeport's school systems are dysfunctional educationally, administratively, and financially and are undergoing audits by the state Education Department even as state government refuses to accept responsibility for their longstanding catastrophic failure and take control of both.

Nor is Trump to blame for the Hartford school system's graduating an illiterate student last year, and presumably many others, nor for the refusal of the city's school superintendent and the state education commissioner to investigate and report about the case.

Trump isn't why the foremost policy of public education in Connecticut is social promotion, which crushes the incentive of students to learn, especially when they lack parenting, as many do.

Racial preferences in government are unconstitutional and unjust, though the country got used to them for many years when they were euphemized as “affirmative action." As a practical matter “diversity, equity, and inclusion" is just a righteous slogan available to euphemize more racial preferences and to distract from the continuing failure of so much of public education.

But if “diversity, equity, and inclusion" ever meant what they should mean -- integration and more equal opportunity -- they might be worth something. The country never will be prosperous, healthy, harmonious, and safe while it keeps creating and sustaining an impoverished and uneducated underclass.

Schools and teachers play the hands they are dealt -- the demographics of their communities. Some schools and teachers are extraordinary but in the end, all together, they will be only average, and, on average, demographics will rule.

So the education problem is far bigger than education itself. It's more a matter of how Connecticut can get more of its children ready and eager to learn in school. It won't be with empty slogans and political posturing.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Evil but calming’

Banner promoting John Kenn Mortensen’s show “Dream Homes,” at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum and Art Center, through Nov. 1

The curator of the show, Brattleboro Museum Director Danny Lichtenfeld, says:

“I can’t remember what I was searching for—or what the algorithm had me chasing—one sleepless night, when I stumbled into the exquisitely creepy world of John Kenn Mortensen’s “Sticky Monsters’’. I was immediately smitten by the oversized, shaggy, more-cuddly-than-scary beasts. As one online commenter has noted, “They’re evil, but also calming. And there’s something very kind about them.

“Based in Denmark, Mortensen is a writer and director of children’s TV shows and the father of twins. The humans in his drawings tend to be children, but they rarely appear scared of the monsters around them. More often, they seem to be getting on as owner and pet, or as friends on a meandering adventure together.’’

Even in the somewhat libertarian Granite state

Apartment building in Manchester, N.H., built in 1864 to house workers in the city’s once-huge textile industry.

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com.

We might do well to watch New Hampshire, where conservative Republicans are joining with Democrats to change communities’ zoning ordinances that, by mandating such things as big minimum-lot sizes (aka “snob zoning”), blocking housing in commercially zoned areas, and very long permitting times have made it very difficult for many places to add to the housing supply.

The Granite State (where I used to live) has long worshipped the glories of local government control, but spiraling housing costs have become enough of a crisis that many state officials increasingly realize that the state must step in to overrule localities’ long-entrenched rules.

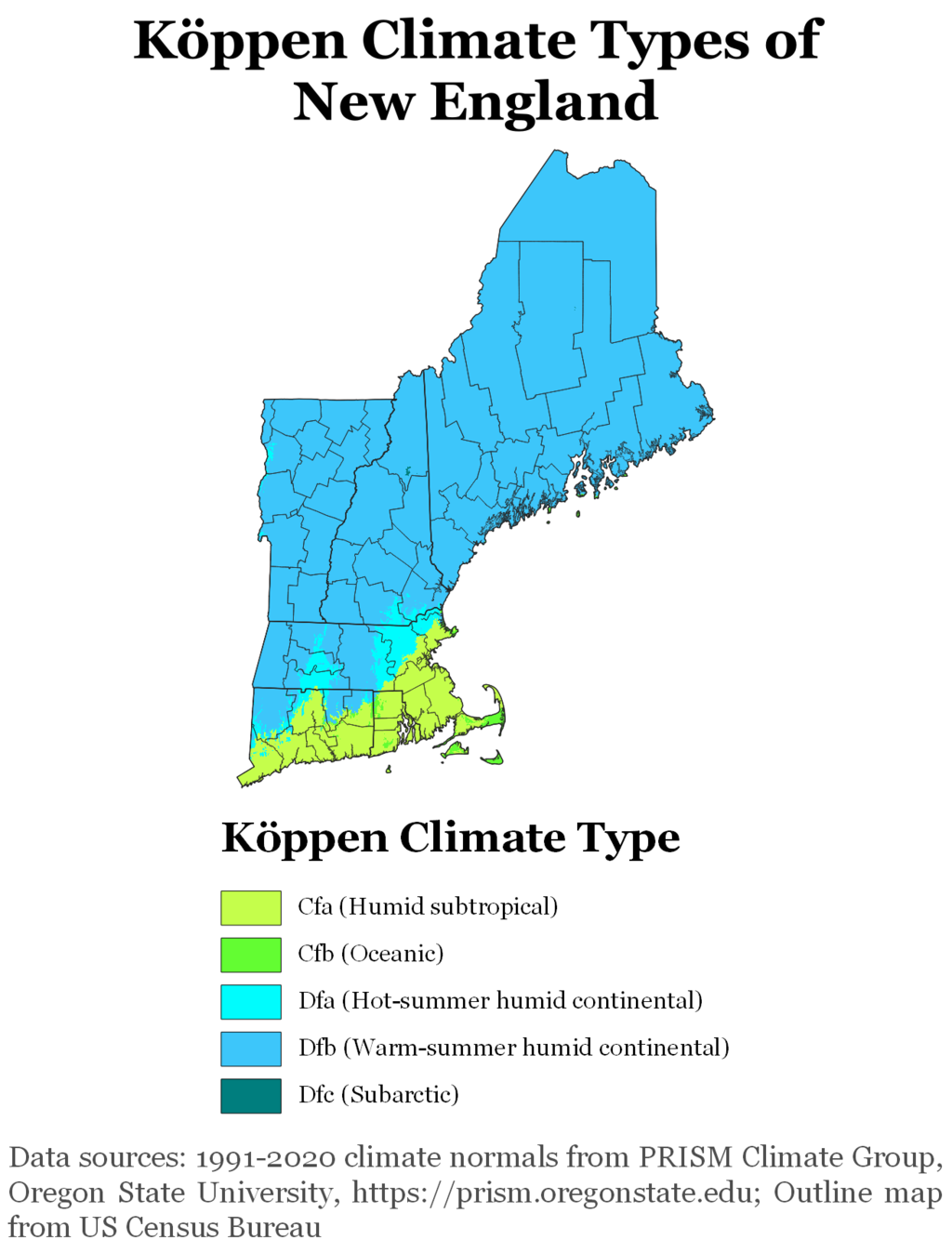

Colonists’ Jarring climate surprise

The yellow and green have been moving north.

From The Colonial Society of Massachusetts

“Of all the preconceptions English people brought with them to New England, perhaps none was so important or so mistaken as that about the American climate.

Colonists came with the common sense idea that climate would be constant in any given latitude around the world. New England, whose latitude is the low forties, was expected to have the climate of Spain or southern France. The debilitating effect of excessive summer heat on English character was the promoters’ main fear in the early years.

What they found, of course, was that New England was in fact very hot in summer but that it was also extremely cold, much colder than England, in winter. Colonists were forced to make sense of their actual experience of America’s climate, explaining why New England deviated from the ‘normal’ European climate, as well as trying to understand what would grow and how life should be constituted here.’’

‘Imagined coastal Images’

“Intertidal,’’ by Phyllis Ewen, in her show “Inundation,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, April 3-June 1

She says:

“I explore how our imagination and memories interact with the natural world. The movement of the earth’s surface has been a source of inspiration and imagery for more than a decade. The surface of the earth has many forces that affect it.

“My ‘Sculptural Drawings’ - three-dimensional reliefs - have been “in the ocean” for many years, but in this show my pieces move on land as the waters flood our coasts.

“Maps, charts, and photographs form the basis for my work. I invite viewers to imagine themselves within the landscape, in topographical waterscapes I scan charts and weather maps, alter them in Photoshop, and print them.

“Then they are reassembled to form imagined coastal images – the effects of anthropogenic global warming.

“Although maps imply a viewer looking down at the landscape, I hope that the dimensional qualities of my images allow us imagine ourselves within it; to inhabit the seas as another way of understanding.’’

Gillette shows plans for Huge Boston Project

P&G Gillette image of Boston project

Edited from a New England Council report

P&G Gillette, has revealed plans for redeveloping its 31-acre Gillette campus in South Boston along the southern edge of the Fort Point Channel.

The 5.7 million-square-foot overhaul will include 1,800 housing units across nine buildings, 3.5 million square feet of office and laboratory space, 200,000 square feet of shops and restaurants, 250,000 square feet for hotel space, and a 6.5-acre public park along the channel.

The new plans come with the company’s program to revamp its two Massachusetts sites, as it relocates its manufacturing out of South Boston to prepare for the 20-building redevelopment. The bulk of the company’s manufacturing will shift to Gilette’s other local property, in Andover, Mass.

The plan awaits feedback from the Boston Planning Department. The entire project could take a decade or more to be completed.

“‘We’ve long been proud of our heritage here in Massachusetts. We’re excited about the legacy we could leave behind through this plan,’ said Kara Buckley, vice president of community affairs at Gillette.

Joanne M. Pierce:What will happen at Pope Francis’s funeral

Pope Francis

Joanne M. Pierce is a professor emerita of religious studies at The College of the Holy Cross, in Worcester.

Joanne M. Pierce does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic appointment.

Except for image above, this is from The Conversation

The 88-year-old pontiff had been well aware of his fragile state and advanced age. As early as 2015, Pope Francis had expressed the desire to be buried in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, a fifth-century church in Rome dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary. He was so devoted to Mary and her basilica that after each of his more than 100 trips abroad, he would visit it after returning to Rome to pray and meditate.

No pope has been buried in Santa Maria Maggiore since the 17th Century, when Pope Clement IX was laid to rest there.

I’m a specialist in Catholic liturgical history. In earlier centuries, papal funerals have been elaborate affairs, ceremonies befitting a Renaissance prince or other regal figure. But in recent years, the rites have been simplified. As Pope Francis has mandated, here are the steps that the ritual will follow.

First station: Preparation of the body

The funeral rites take place in three parts, called stations. The first takes place in the pope’s private chapel, after medical professionals have certified his death. Until recently, this stage had taken place at the pope’s bedside.

After the body lies in rest in the chapel, the cardinal serving as the pope’s camerlengo – the pope’s chief of staff – will make the arrangements for the funeral. He is also tasked with running the Vatican until a new pope is elected. The current camerlengo is Cardinal Kevin Joseph Farrell, appointed by Francis in 2019.

As has been done for centuries, the camerlengo will formally call the deceased pope by the full name given to him when he was baptized as an infant – Jorge Mario Bergoglio. There are narratives or legends stating that, at this time, the pope was also tapped three times on the forehead with a small silver hammer. However, there is no documented proof that this was actually done in earlier centuries to verify a pope’s death.

Traditionally, another ancient rite will also take place after the declaration of the pope’s death: the defacing of the pope’s ring. Each pope wears a custom-made ring with an engraved image of a man fishing from a boat, hearkening back to the gospel of Matthew, where Jesus calls St. Peter a “fisher of men.” This Fisherman’s Ring, with the name of the current pope engraved over the image, could act as a seal on official documents. The camerlengo will break Francis’ ring and smash the seal with a hammer or other instrument to prevent any other person from using it.

The pope’s apartments will also be locked, with no one allowed to enter; traditionally, this was done to prevent looting.

Second station: Viewing the body

The deceased pope will be dressed in his simple white cassock and red vestments, then placed in a simple wooden coffin. This will be carried in procession to St. Peter’s Basilica, where the public viewing will take place for the next three days.

The pope’s body will be left in the plain, open casket during this viewing period in order to emphasize the pope’s humble role as a pastor, not a head of state. The earlier practice would have been to place the body on top of a tall raised platform, called a catafalque; this ended with the funeral of Pope Benedict XVI in 2022.

Pope Benedict was also the last pope to be buried in the traditional three coffins of cypress, lead and elm. Two coffins contained specific documents about his pontificate; the first coffin also held the traditional three bags of coins – gold, silver and copper – representing each year of his pontificate.

At Francis’s funeral, after the public viewing, a plain white cloth will be placed over the pope’s face as he lies in the oak coffin, a continuing part of papal funerals. But this will be the first time that only a single coffin will be used; it will likely contain a document describing his pontificate and a bag of coins from his pontificate as well.

The funeral Mass will then be celebrated at St. Peter’s, and there will likely be a crowd of believers outside, assembled on the plaza. The homily will reflect on the life and spirituality of the deceased pope; Francis himself preached at the funeral of his retired predecessor, Pope Benedict. And the future Pope Benedict, as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, preached at the funeral of Pope St. John Paul II when Ratzinger was the leader, or the dean, of all senior church officials – what’s known as the College of Cardinals.

The current dean is 91-year-old Cardinal Giovanni Battista Re, and it is unclear whether he will be able to continue this tradition due to his advanced age. Masses will continue to be said in Francis’ memory for nine days after his death – a period called the Novendialis. This ritual was inspired by an ancient Roman tradition prescribing a mourning period ending on the ninth day after a death.

Third station: Burial

Why does Pope Francis want to be buried in St. Mary Major and not in the Vatican?

Popes in the past have been buried in several different places. Until the legalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire in the early fourth century, popes would be interred in the catacombs, the burial grounds on the outskirts of Rome.

Afterward, popes could be buried in a number of different locations, such as the Basilica of St. John Lateran – the official cathedral of Rome – or other churches in and around Rome. A few were even buried in France during the 14th century, when the papacy moved to the French border for political reasons.

Most popes are buried in the grottoes underneath St. Peter’s, and since Pope Leo XIII’s burial at St. John Lateran in 1903, every pope has been buried at St. Peter’s. According to Francis’ wishes, however, there will likely be a procession across Rome to Santa Maria Maggiore, including the hearse and cars carrying others who will attend this private ritual.

After a few final prayers and sprinkling of holy water, the coffin will be placed in its final location inside the church. Only later will the area be opened to the public for prayers and veneration.

After so many journeys from Rome to visit Catholic communities in countries across the globe, and so many visits to this basilica for prayer and meditation, it seems fitting that, at the end of his life’s journey, Francis would make one last trip to the church he loved so much to be laid to rest forever.

Holding Hands in the fake forest

Norway spruce

“In the false New England forest

where the misplanted Norwegian trees

refused to root, their thick synthetic

roots barging out of the dirt to work on the air,

we held hands and walked on our knees.''--From “The Expatriates,'' by Anne Sexton (1928

-1974), Massachusetts poet

The honor of being Booed

Pedro Martinez in 2010.

“It actually made me feel really, really good. I actually realized that I was somebody important, because I caught the attention of 60,000 people, plus you guys [reporters], plus the whole world watching a guy that if you reverse time back 15 years ago, I was sitting under a mango tree without 50 cents to actually pay for a bus. And today I was the center of the attention of the whole city of New York.’’

— Former Red Sox pitcher Pedro Martinez (born 1971) on being booed by Yankees fans at Yankee Stadium on Oct. 13, 2004 in Game 2 of the American League Championship series.

Down to essentials

“Sun, Manana, Mohegan” (1907 oil on canvas), by Rockwell Kent (1882-1971), in the show “Art, Ecology, and the Resilience of a Maine Island,’’ at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, through June 1.

Global Warming Throws off New England species

A Saltmarsh Sparrow. The species is predicted to go extinct in the next 15 to 20 years as rising sea levels flood marshes along the East Coast.

Text excerpted from an ecoRI News article

“This is part of an ecoRI News series called Wild New England . The region’s collection of native species is under threat on several fronts, most notably from humanity’s shortsightedness. Humans aren’t giving the natural world the space it needs and deserves. We’re crowding out non-human life, which, in turn, makes nature less productive and us less healthy. Wild New England examines the animals and insects most at risk.’’

“The work of Charles Clarkson, the Audubon Society of Rhode Island’s director of avian research, has documented the challenges birds face as the climate crisis increases the unpredictability of weather. Species that have timed their migratory movements over thousands of generations to coincide with gradual spring warming or autumn cooling are finding themselves out of whack with the plant and insect communities they rely on.

“This climate mismatch is leading to avian population declines, particularly with those species that undergo long-distance migration, such as the common yellowthroat, the wood thrush, and the American goldfinch.’’