George McCully: America’s crisis of knowledge

Pinoccchio

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

There has been a growing consensus among authorities, especially in the Trump era, that the U.S. is in an epistemological crisis that threatens our democracy.

Former President Obama, for example, in a recent Atlantic interview, said: “If we do not have the capacity to distinguish what’s true from what’s false, then by definition the marketplace of ideas doesn’t work. And by definition, our democracy doesn’t work. We are entering into an epistemological crisis.”

If this is true, it is an issue which the academic and journalistic communities—i.e. those in charge of the public’s knowledge and education nationwide—need to address.

There are plenty of indications that Obama was right. The 2020 election intensified this awareness. David Brooks, in his New York Times column of Nov. 27, wrote that “77 percent of Trump backers said Joe Biden had won the presidential election because of fraud. Many of these same people think climate change is not real. Many of these same people believe they don’t need to listen to scientific experts on how to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. We live in a country in epistemological crisis, in which much of the Republican Party has become detached from reality.”

On that same day, Michael Gordon, in an op-ed for The Washington Post, wrote: “Journalism is important, and there should be more of it. An informed electorate, in the long run, will have better democratic outcomes. But the urgent problem of American politics is not an insufficient airing of policy disagreements; it is that policy views have become a function of cultural identity. A matter such as climate disruption, for example, attracts comparatively little informed and reasoned disagreement. Climate skepticism has become a tenet of populism—a revolt against elitist scientists and liberal politicians seeking excuses for social and economic control. The denial of climate change has become a cultural signifier, the policy equivalent of a gun rack in a truck.”

Multidimensional crisis

The crisis has several dimensions beyond the intellectual one. Robin Givhan, in her Washington Post column on Feb. 17, 2021, reported: “Surveys have shown that political polarization along educational lines has deepened. The gap between college-educated voters and non-college-educated voters has grown steadily over the past 60 years. The 2020 presidential election hinged on the diploma divide, which in turn, contributes to differences in income, household wealth, jobs, place of residence, cultural values and access to opportunity. … For the past four decades, incomes rose for college degree holders even as they fell for those without one, generating frustration, resentment and anger. With nearly three-quarters of new jobs requiring a bachelor’s degree, excluding nearly two-thirds of adults, earnings are linked to learning in ways that weren’t true during the 1950s and 1960s.”

There is also a technological dimension. Whereas it used to be thought that the internet would enhance democracy, we have seen an opposite effect. Thomas Edsall, in The New York Times, also on Feb. 17, wrote that “a decade ago, the consensus was that the digital revolution would give effective voice to millions of previously unheard citizens. Now, in the aftermath of the Trump presidency, the consensus has shifted to anxiety that such online behemoths as Twitter, Google, YouTube, Instagram and Facebook have created a crisis of knowledge—confounding what is true and what is untrue—eroding the foundations of democracy.”

Nathaniel Persily, a Stanford University law professor, summarized the dilemma in his 2019 report, “The Internet’s Challenge to Democracy: Framing the Problem and Assessing Reforms.” He wrote that “in a matter of just a few years the widely shared utopian vision of the nternet’s impact on governance has turned decidedly pessimistic. The original promise of digital technologies was unapologetically democratic: empowering the voiceless, breaking down borders to build cross-national communities, and eliminating elite referees who restricted political discourse. Since then that promise has been replaced by concern that the most democratic features of the internet are, in fact, endangering democracy itself. Democracies pay a price for Internet freedom, under this view, in the form of disinformation, hate speech, incitement and foreign interference in elections.”

He continued, “Margaret Roberts, a University of California-San Diego political scientist, says bluntly, ‘The difficult part about social media is that the freedom of information online can be weaponized to undermine democracy.'” In an email to Edsall, she wrote, “Social media isn’t inherently pro[-] or anti-democratic, but it gives voice and the power to organize to those who are typically excluded by more mainstream media. In some cases, these voices can be liberalizing, in others illiberal.” We are reminded that while Franklin Roosevelt used radio for fireside chats to promote his liberal agenda, Hitler was using it to promote his fascism.

Today, the new technology is more dangerous, because with AI, it becomes progressively easier to disguise mis- or disinformation as authentic news, and to scrape data from users’ devices to then target the citizens most likely to be vulnerable to dissuasion. Training in “media literacy” or how to discern authentic from fraudulent communication especially on the web, has been a growing field for decades, and will continue to be so as technology advances. But communications techniques and evaluation of sources are less our concern here than epistemology per se, and, in particular, reliance upon trusted sources, which most people use as their criterion for recognizing truth.

The truth is out there?

What is to be done? First, let us understand that the principal constituency bearing civic responsibility for the health and welfare of public intelligence, has to be scholars and educators, including journalists; and that in these roles, our professional and technical focus must be less on the economic, technological or even psychological and moral dimensions of the epistemic (i.e. relating to knowledge) crisis than on its epistemological (i.e. the study or science of knowledge) core.

We notice that the journalistic discussions quoted above focus on trust as the main issue—i.e., whom people should or want to believe in matters of science, public policy or politics and how trustworthiness has been subverted by political, economic and technological developments. While it is probably true that this is how most people actually know and think, as scholars we do not and, in fact, are trained not to trust even one another, because trust is an invalid and unreliable criterion of truth. From our professional perspective, public trust itself is intrinsic to the public’s epistemological crisis.

Another intrinsic element of that core obviously is inadequate factual knowledge or sheer ignorance of how and why our government works. On our watch over the past 50 years, there has been a steady erosion in the teaching of civics and history. While we spend about $50 per student annually on science and math education, only about five cents is allocated to civics education. Ten states currently have no civics requirement in schools. Large numbers of Americans cannot even name the three branches of government, never mind the value for democracy of checks and balances, or how elections are essential for peaceful transfers of power. This past year we have seen how misunderstanding of governmental politics has fed distrust, non-participation and polarization. The federal government is aware of this and has developed a purportedly high-quality K-12 civics and history program called “Educating for American Democracy,” but it has not been funded for implementation. While this initiative might help to address the knowledge issue,it does not address the crisis in epistemology—confusion about how to know and recognize truth.

Many years ago, on my first day at Brown University, the freshman class assembled in Sayles Hall to be welcomed by the university’s president, Barnaby Keeney (later the founding director of the National Endowment for the Humanities). He told us that one of the most essential and valuable skills we would learn in college—central to every scholarly discipline as the most reliable way to think about the world—was “to think on the basis of evidence.” That simple phrase—this was the first time I had heard it—blew me away, and has stuck with me for life.

Several years later, while studying history in graduate school at Columbia University, I recall discussions we often had with fellow students in one of the nation’s leading schools of journalism. They were being taught to build their stories around “balance” among various contending points of view, as a “fair” way to report to the public on current events. We history students considered this absurd, ridiculous and misleading to the public, implying that all points of view are equally valid and significant. We were right, but we see today that “balance” has set the modern standard in journalism, still practiced and still, as predicted, pernicious and dangerous. I have been amazed at how leading journalists these days struggle to articulate the challenge of ascertaining truth, treating it as discovering whom to trust. They rarely use the word “evidence”—a rare exception is Lester Holt of NBC Nightly News, who said recently in accepting the Edward R. Murrow Award for Lifetime Achievement in Journalism, “I think it’s become clearer that fairness is overrated,” and he advocated that reporters not give “unsupported arguments” equal coverage.

Follow the evidence

About the only venue where “evidence” has been determinative in current politics is our court system, wherein attempts by Trumpists to quash results of the last presidential election on grounds of corruption were summarily rejected by 63 courts at all levels nationwide for their total “lack of evidence.” The words were quoted by reporters of those decisions, and gradually the criterion of “evidence” has begun to be used comfortably by leading journalists, though we do not know if they appreciate its epistemological value—in fact, necessity in determining truth.

But the health of our democracy cannot safely rely solely on our judiciary and the best of journalism, which brings us back to the issue of our proper civic responsibilities, as scholars and teachers, for the health of public thought and discourse. What can we do to help resolve our national epistemological crisis, to protect our democracy?

First, we need to promote, for all courses and disciplines in all colleges and universities, explicitly and emphatically, that the best—i.e., surely, most reliable—way to think about the world is “on the basis of evidence.” We must work to help make it consciously automatic and habitual for all who are in or have been to college.

Second, and this is critically important, there is no reason “thinking on the basis of evidence” cannot also be taught as the explicit standard and simple lesson throughout secondary schools nationwide. We need to promote this pedagogy in every way we can, including in the media, to eliminate the apparent political divide between citizens who have been to college and those who have not. There is no justification for this particular separation in our body politic.

Third, we need to promote at every opportunity stronger academic, journalistic and media offerings in American history and civics, to combat the widespread ignorance that has also undermined our politics.

Fourth and finally, we need to promote to journalists their need to habitually ask, as the first question after hearing any political opinion or unsupported assertion, “What’s your evidence?”, and if none is forthcoming, to report that fact—that non-event as an event, that the dog didn’t bark, as it were—an integral part of their stories. This past year, it took far too long for that to happen with countless baseless assertions about the election. Journalism is a teaching profession; its responsibility is to provide the first or early accounts of current history for public use and information. Journalistic “fairness” should be to truth in public record, not to all sides of contentions in controversies.

We cannot and do not expect epistemological problems, much less crises, to be successfully resolved for all parties in any specific time frame. All I am advocating here is a concerted effort on the part of as many of us as possible to achieve a better—more constructive—balance in public discourse, between efforts to promote respect for truth, and efforts to promote partisanship with no respect for truth. I have attempted to identify the main parties responsible for truth in civic and political packaging—i.e., scholars, educators and journalists—who are all our public’s teachers. These responsible parties must work much harder to promote “thinking on the basis of evidence” rather than trusting people or institutions as a way of learning truth, on which the health of our democracy necessarily depends.

George McCully, a historian, has been a former professor and faculty dean at higher- education institutions in the Northeast, then professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.

Keeps them moving

“Geisha-Revue, The Dance on the Volcano’’ (1911/13, oil on canvas), by Georg Tappert, at the Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art, Hartford. It’s part of the show “The Dance on the Volcano: German Expressionism at the Wadsworth,’’ through May 30.

Jim Hightower: Wall Street moves in on water

— Photo by José Manuel Suárez

From OtherWords.org

Oh great — here comes a new stealth attack on the fragile, life-sustaining natural resources of Planet Earth. This latest assault by Wall Street alchemists would redefine one of our most basic resources: water.

Everyone knows that water is “invaluable” — it’s literally life, requiring a constant intake by each of us, or we quickly die. But the Wizards of Wall Street want to reduce potable H2O from its environmental, humanitarian and spiritual essence to just another perishable economic good that they can market-price and sell to the highest bidder — turning our water into speculators’ gold.

This contrivance has opened the door for financial manipulators who’ve quietly been devising razzle-dazzle schemes to allow rich global investors to play in water. They’re now pushing water futures, automated split-second trading, “water grabbing” ventures, hedging schemes, and other financialization hustles to maneuver the monetary value of this essential resource.

To see this ethically debased future, look to an outfit with the ominous acronym of WAM (Water Asset Management).

WAM is buying up water rights in low-income farming communities in places like Arizona, then literally moving the “commodity” to rich suburban developments that will pay more. WAM profiteers call water peddling “the biggest emerging market on Earth… a trillion-dollar market opportunity.”

They even boast that the crises of “drought, flood, and fire” caused by climate change creates a market volatility that will provide “an unprecedented period of transformation and investment opportunity for the water industry,” allowing investors to “thrive and prosper.”

We need to force a public discussion about this crucial question of environmental and existential ethics: Is access to an affordable supply of clean water to be a human right for all — or will we let it become a wet dream for rich speculators.

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer, and public speaker.

Philip K. Howard: Paralyzing ‘rights’ are used against the public interest; bring back fair accountability

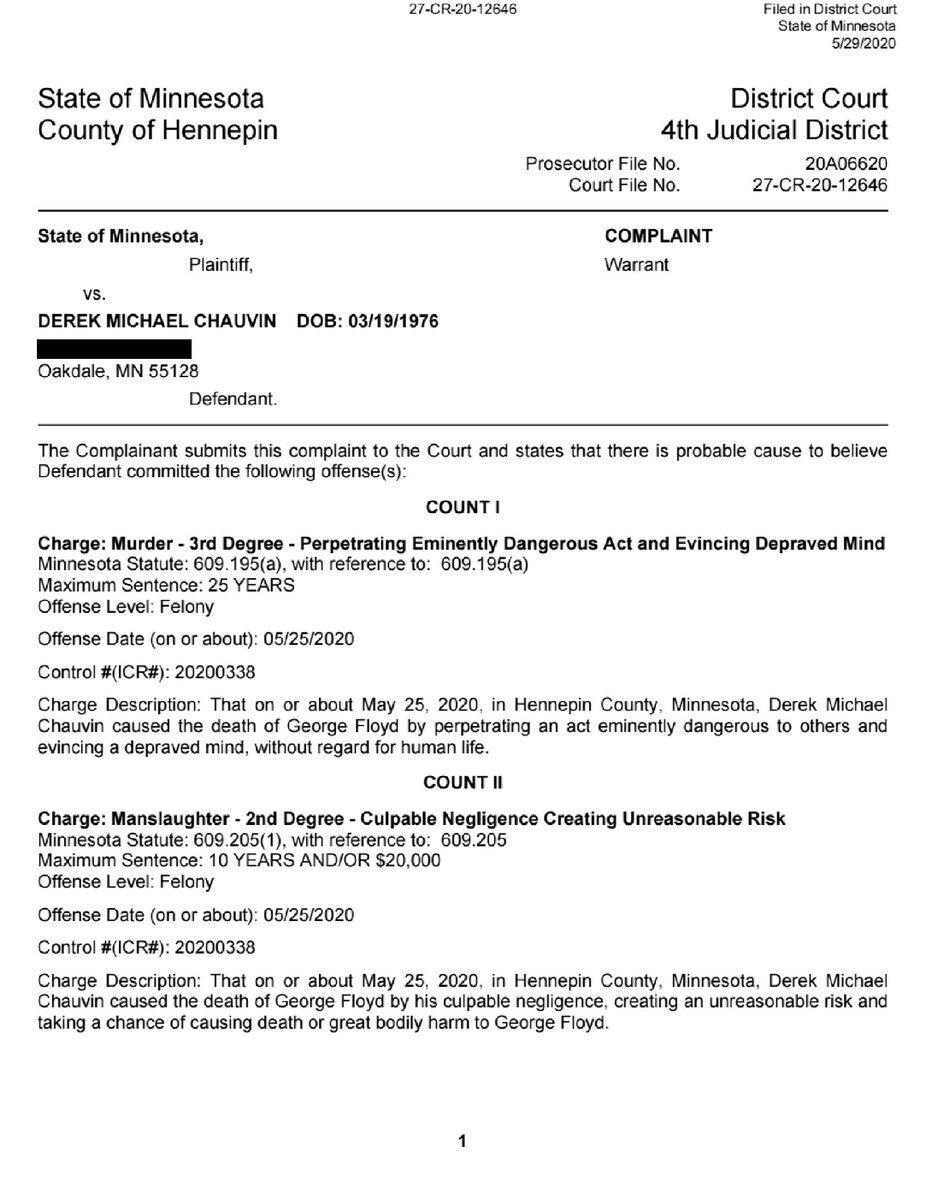

The conviction of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for killing George Floyd may elevate trust in American justice, but it will do little, by itself, to repair trust in police. Nor can political leaders and their appointees do much to restore that trust, because police “rights” still render officers virtually immune from accountability and basic management decisions. Chauvin was known to be “tightly wound,” and the police department had previously received 18 complaints about him abusing his power. Despite the complaints, he was not terminated or transferred. He had his rights.

But what about the public’s rights against abusive officers? We should be protected from bad cops, of course, but we can’t get there using the language of rights. Analyzing public accountability as a matter of rights is circular: Whose rights?

Rights rhetoric sprung out of the 1960s to defend freedom against institutional discrimination. But rights have evolved into an offensive weapon against the legitimate interests of other citizens—by police to avoid accountability, by teachers to avoid returning to work, by journalists and academics to cancel offensive speech.

The fabric of a free society is torn by these self-interested rights. Upholding values like fairness, reciprocity, and mutual respect is difficult when individual rights preempt the rights of everyone else.

The solution is simple: Hold people accountable again. Take “tightly wound” cops off the beat. If college students cancel other students’ freedom to hear a speaker, invite the cancelers to matriculate elsewhere. Healthy teachers who claim their potential covid exposure entitles them not to teach should find other jobs: Why should they be more privileged than nurses and grocery clerks?

But there’s a hitch: Holding people accountable is claimed to violate their rights. We seek more justice, fairness, and freedom, but we deny ourselves the tool of accountability needed to accomplish these goals.

It’s time to reset the balance between public accountability and concerns about individual fairness. Accountability must be taken out of the penalty box: Restore the freedom, up and down the chain of responsibility, to make judgments about other people and their actions. We can provide safeguards against unfairness, but law should intercede only where there is systemic discrimination or demonstrated harassment.

A Condition of Freedom

Every day, each of us evaluates the people we deal with. These judgments about other people influence how we associate, come together, and strive to achieve our private and societal goals.

People judging people is the currency of a free society.

We think of accountability in its negative sense—as the stick for inadequate performance. But accountability is needed for a positive reason—to instill the mutual trust that everyone is doing their share. It assures mutuality of effort and values. Coworkers need to believe that energy, virtue, and cooperation will be rewarded while mediocrity, indifference, and selfishness will not be tolerated.

The paradox of accountability is that once it’s available, it rarely needs to be exercised. What’s important is the availability of accountability. Once mutual trust and obligation are established, an energetic and cooperative culture leads people to do their best.

Accountability is also the organizing principle of democracy: voters elect leaders who preside over an unbroken chain of accountability down to subordinate officials. But the links in our chain of accountability are broken. Police chiefs, school principals, and government commissioners have lost their ability to hold their personnel accountable. Over 99 percent of today’s federal employees receive a “fully successful” job rating. California has one of the country’s worst school systems but can terminate no more than two or three teachers per year for poor performance. In New York, a teacher who went to jail for selling cocaine had to be reinstated in his job after his release. Under Minneapolis’ collective bargaining agreement with its union, the city’s police chief couldn’t even reassign Derek Chauvin for past misconduct, let alone terminate him, without a legal proceeding.

Democracy can’t function effectively without accountability. The conditions for social trust disappear. One effect is widespread anger and resentment at people acting irresponsibly or demanding things they don’t deserve. Society goes into a downward spiral of cynicism and selfishness. Sometimes people take to the streets.

The Illusion of Objectivity

Most people probably support the idea of accountability; but who decides, and on what basis? Most experts and academics think the job can be defined by metrics, “key performance indicators,” or other unimpeachable criteria. The Supreme Court has embraced this idea: Thus, one dubious innovation of the 1960s rights revolution was the application of due process to public personnel decisions. “It is not burdensome to give reasons,” Justice Thurgood Marshall stated, “when reasons exist.”

But “objective” accountability leads inexorably to no accountability. Being a good cop, teacher, or coworker is more complex than can be defined by objective criteria. Focusing too much on metrics—test scores, arrests, quarterly profits—will skew behavior in ways that are typically destructive. As Jerry Muller puts it in The Tyranny of Metrics (2018), measurement is useful as a tool of human judgment but not a replacement for it.

Thus, the No Child Left Behind law held schools accountable for increases in test scores—and turned many schools into drill sheds. Some school officials, supposedly role models for our youth, were caught in organized cheating schemes. In a similar way, judging surgeons by their mortality rates led many to avoid the difficult surgeries that require the most skill. Paying corporate employees according to short-term sales or profits means they will act in ways that undermine long-term corporate health.

Successful accountability rarely involves black-and-white choices. The most important qualities of employees can’t be captured by objective criteria. Good judgment, a can-do attitude and a willingness to help others can be readily identified by co-workers but are not objectifiable.

A KIPP charter school principal described to me a teacher who looked perfect on paper and tried hard but could not succeed:

He just couldn’t relate to the students. It’s hard to put my finger on exactly why. He would blow a little hot and cold, letting one student get away with talking in class and then coming down hard on someone else who did the same thing … but the effect was that the kids started arguing back. It affected the whole school. Kids would come out of his class in a belligerent mood.… We worked with him on classroom management the summer after his first year. It usually helps, but he just didn’t have the knack. So, we had to let him go.

In The Moral Life of Schools (1993), a landmark study of the traits that distinguish effective teachers, Philip Jackson and his colleagues concluded,

Laying aside all exceptions, … there is typically a lot of truth in the judgments we make of others. And this is so even when we cannot quite put our finger on the source of our opinion. That truth, we would suggest, emerges expressively. It is given off by what a person says and does, the way a smile gives off an aura of friendliness or tears a spirit of sadness.

To complicate accountability judgments, they involve not just particular persons but the way they perform in particular settings. An effective grade-school teacher may be ineffective teaching high school. “Men are neither good nor bad,” as management expert Chester Barnard observed, “but only good or bad in this or that position.”

Today, the most important criteria for fair accountability are irrelevant because they’re not objectively provable. Some of the qualities “considered too subjective to stand up in court,” as Walter Olson notes in The Excuse Factory, include these: “temperament, habits, demeanor, bearing, manner, maturity, drive, leadership ability, personal appearance, stability, cooperativeness, dependability, adaptability, industry, work habits, attitude toward detail, and interest in the job.” How could the Minneapolis police chief prove that Derek Chauvin was too tightly wound?

The Irreducibility of Human Judgment

Reviving accountability requires coming to grips with the reality that it always requires subjective judgments, in context, about the relative performance of each employee. Since the 1960s, America has rebuilt its governing structures to eliminate human judgment as far as possible. Letting people make judgments about others leaves room for unfairness or bias. Who are you to judge? Worse, we’re told to distrust our own judgments as vulnerable to unconscious bias. How can we protect against that?

What’s needed is a new protocol that instills some level of trust in accountability judgments without getting mired in rigid rights, metrics, and near-endless legal arguments. The obvious solution is to restore the legitimacy of human judgment not only for supervisors but also for other stakeholders. Studies suggest that coworkers usually have a consensus view on who’s good and who’s not: “Everyone knows who the bad teacher is.”

A school could have a parent-teacher committee with authority to veto unfair termination decisions. A police department could have an accountability review committee comprised of police, prosecutors, and citizen representatives. Private companies like Toyota have workers’ councils that give opinions before an employee is let go.

Oversight committees are hardly infallible but can provide speed bumps against supervisory unfairness. Discriminatory practices can still be reviewed by courts or other authorities where there are credible allegations of systemic discrimination.

But the pervasive overhang of legal threats for personnel judgments must be removed. Legal proceedings asserting individual rights against accountability will be irresistible to many affected workers. Nature has wired people to self-justify, and the accountable individual, studies show, is uniquely incapable of judging the fairness of such a decision. How well anyone does in an organization, Friedrich Hayek put it, “must be determined by the opinion of other people.”

We’re trained to be reluctant to let people judge other people; we want legal proof. But putting personnel judgments through the legal grinder is even less reliable. How do you prove which person doesn’t try hard, or which teacher can’t hold students’ attention?

Journalist Steven Brill described one 45-day hearing to try to terminate a teacher who was not only inept but didn’t try. She never corrected student work, filled out report cards, or met even the most rudimentary responsibilities. Her defense? There was no proof that she had been given an instruction manual telling her to do these things. This type of sophistry is typical in due process hearings: As one union official put it, “I’m here to defend even the worst people.”

Cooking accountability in a legal cauldron is in most circumstances a recipe for bitterness and frustration. The personal disappointment of a job not working out, which would be quickly forgotten if the person got a new job, becomes a kind of holy war, consuming the life of the individual supposedly protected. Discrimination lawsuits are notorious for both their high emotions and their low success rate. A federal judge told me about a case in which the evidence was overwhelming that the employee was not up to the job—but the worker was in tears at the injustice done to him.

Honoring Everyone Else’s Rights

No human grouping can long survive if its members flout accepted norms of right and wrong or tolerate failure as normal.

The quest to make accountability a matter of objective proof has turned out to be a blind alley, leading inexorably to unaccountability. No one should have the right to be unaccountable. Any claim of superior rights violates everyone else’s rights. Rights are supposed to protect against unlawful coercion, not against the judgments of other free citizens or the choices needed to manage an institution.

Putting the magnifying glass on the accountable individual ignores the rights of other affected individuals. What about the unfairness to coworkers and the public of having to deal with an uncooperative or inept person? For institutions, removing accountability is like pouring acid over workplace culture. The 2003 Volcker Commission on the federal civil service found deep resentment at “the protections provided to those poor performers” who “impede their own work and drag down the reputation of all government workers.” That’s why America’s public culture too often lacks energy, pride, and effectiveness.

Democracy fails when public institutions can’t do their jobs properly. As demonstrated by abusive cops and inept teachers, viewing accountability as a matter of individual rights means that police, schools, and other social institutions can’t serve the public effectively. Democracy becomes vestigial, a process of electing figureheads who have little effective authority over the way government operates.

In all these ways and more, the loss of accountability has eroded the rights and freedoms of all Americans, compromising much of what is admirable and strong in American culture. Good government is impossible unless officials have room to use their common sense, but no one will trust officials without clear lines of accountability.

Like putting a plug back in a socket, restoring accountability will reenergize human initiative in government and throughout society. Most people want the freedom and self-respect of doing things in their own ways and the camaraderie of working with others who also value human initiative. But the freedom to take initiative has one condition: accountability. Individuals cannot be immune from the judgments of others without undermining freedom itself.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based civic leader, author, lawyer and photographer, is founder of Common Good (commongood.org) and author, most recently, of Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left (2019). This essay first appeared in American Purpose

Using AI in remote learning

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“In partnership with artificial intelligence (AI) company Aisera, Dartmouth College recently launched Dart InfoBot, an AI virtual assistant developed to better support students and faculty members during the pandemic. Nicknamed “Dart,” the bot is designed to improve communication and efficiency while learning and working from home, with mere seconds of response time in natural language to approximately 10,000 students and faculty on both Slack and Dartmouth’s client services portal.

“The collaboration with Aisera allows for accelerated diagnosis and resolution times, automated answers to common information and technology questions, and proactive user engagement through a conversational platform.

“At Dartmouth, we wanted our faculty and students to have immediate answers to their information and technology questions online, especially during COVID. Aisera helps us achieve our goals to innovate and deliver an AI-driven conversational service experience throughout our institution. Faculty, staff, and especially students are able to self-serve their technology information using language that makes sense to them. Now our service desk is free to provide real value to our clients by consulting with them and building relationships across our campus.” said Mitch Davis, chief information officer for Dartmouth, in Hanover, N.H.’’

The field of artificial intelligence was founded at a workshop on the campus of Dartmouth during the summer of 1956. Those who attended would become the leaders of AI research for decades. Many of them predicted that a machine as intelligent as a human being would exist in no more than a generation.

The greatest need for new Amtrak money

Sections owned by Amtrak on the Northeast Corridor are in red; sections with commuter service are highlighted in blue.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Politicians across America, even anti-“Big Government” right-wingers in rural states, want Amtrak service, some of it as local pork, however lightly it is used. But as Congress considers President Biden’s almost $2 trillion infrastructure program, and the $80 billion in it for Amtrak, they should, but might not, set aside the lion’s share of the money to improve the Northeast Corridor, where it’s by far the most needed.

That where the nation’s thickest population density is; such density is very important in justifying rail passenger service. And the great popularity of the service, between Boston and Washington, D.C., has been demonstrated for decades.

The Northeast Corridor line plays an important part in lubricating the economy of this immensely important part of America, which includes both its political (Washington) and financial (New York) capitals as well as crucial technological, education and health-care infrastructure. Amtrak service there should be expanded, for economic and environmental reasons.

Amtrak owns and controls some 80 percent of the Corridor, which means, importantly, that it has considerable control over how the few freight trains use it on short sections. New York State, Connecticut and Massachusetts, for their part, own relatively sections of the route. But Amtrak is in the driver’s seat, as it should be. That isn’t to say that at least one more set of tracks, for freight and passengers, hasn’t long been needed.

You must expect that if all or part of the Biden infrastructure package is approved, that Amtrak service to thinly populated and economically insignificant parts of the country will be preserved or even expanded with lightly used long-haul trains (much beloved by train romantics), especially in states with powerful members of Congress. So be it in legislative sausage-making, but the core need for the benefit of the entire country is the Northeast Corridor.

xxx

Note the importance of Providence’s Amtrak stop not only for Rhode Islanders but for the many people from southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Connecticut who also use it, for Amtrak and MBTA service.

An Amtrak Acela train in Old Saybook, Conn.

David Warsh: Of shadowy commodities traders, ‘tropical gangsters’, deluded crowds

At the Chicago Board of Trade before the pandemic

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Because my tastes are well-established, I sometime receive new books that otherwise might escape readers’ attention. Herewith some recent arrivals.

The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources (Oxford), by Javier Blas and Jack Farchy. A pair of former Financial Times commodities reporters, both now working for Bloomberg News, Blas and Farchy explore the shadowy world of billionaire commodity trading firms – Glencore, Trifigura, Vitol, Cargill, and the founders of the modern industry, Phillip Brothers and Marc Rich. Firms and individuals whose business is trading physical commodities – fossil fuels, agricultural commodities, metals and rare earths – enjoy a unique degree of privacy and autonomy, except from market forces. Blas and Farchy illuminate the goings-on in an otherwise almost unnoticed immense asset class ordinarily tucked away in the interior of newspapers’ financial pages.

The Culture and Development Manifesto (Oxford), by Robert Klitgaard. Remember Tropical Gangsters: Development and Decadence in Deepest Africa?

The New York Times Book Review called Klitgaard’s tale of adventures during two-and-a-half years in Equatorial Guinea one of the six best nonfiction books of 1990. The author is back, summing up various lessons learned during 30 more years advising nations, foundations, and universities on how to change (and not change) their ways. Why a manifesto? His determination, with the same good humor as before, to persuade economists and anthropologists to work together, the better to understand the context of the situations they seek to change.

The Day the Markets Roared: How a 1982 Forecast Sparked a Global Bull Market (Matt Holt Books), by Henry Kaufman. What was Reaganomics all about? Plenty of doubt remains. There is, however, no doubt about the forecast that triggered its beginning. Salomon Brothers’ long-time “Dr. Doom” recalls the circumstances surrounding the “fresh look” he offered of the future of interest rates on Aug. 17, 1982. In doing so, he reconstructs a lost world. The Dow Jones Industrial Average soared an astonishing 38.81 points the next day – its greatest gain ever to that point.

The Delusions of Crowds: Why People Go Mad in Groups (Atlantic Monthly Press), by William J. Bernstein. A neurologist, author of The Birth of Plenty: How the Prosperity of the Modern World Was Created (McGraw-Hill, 2010), Bernstein tracks the spread of contagious narratives among susceptible groups over centuries, from the Mississippi Bubble and the 1847 British railway craze to the Biblical number mysticism of Millerite end-times in 19th Century New England and various end-time prophecies in the Mideast. Such behavior is dictated by the Stone Age baggage we carry in our genes, says Bernstein.

Albert O. Hirschman: An Intellectual Biography (Columbia), by Michele Alacevich. It was never hard to understand the success of Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman, by Jeremy Adelman, a Princeton University professor and personal friend of the economist and his wife. Hirschman cut a dashing figure. He fled Berlin for Paris in the ’30s, studied economics in London, fought with the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, moved to New York, and returned to wartime France to lead refugees fleeing the Nazis over the Pyrenees, from Marseilles to Barcelona. As a historian, biographer Adelman was less attuned to Hirschman’s subsequent career as an economic theorist – of development, democracy, capitalism, and commitment. Alacevich has provided a perfect complement, a study of the works and life of the author of the classic, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.

'Biological batteries'

Work from the show “Justin Kedl: ATOMIC GERMINATION,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, through May 30.

The gallery says:

“Kedl’s installation features a colorful collection of biomorphic ceramic forms fanning out across the wall, flowering like an alien cartoon garden. Behind the humor and visual delight of this strange colony of organisms, the artist has conjured a hopeful narrative rooted in science fiction. Kedl imagines these creatures as biological batteries from the near future, genetically engineered to feed on the most toxic byproducts of human industry—micro plastics, oil spills, radioactive waste—and convert them into clean energy that can be harnessed to power our everyday lives. Kedl notes that the work offers ‘an alternative to the normal doom-and-gloom of environmental discourse and uses science fiction as a means of imagining a more hopeful future where human progress can heal the earth rather than harm it.’’’

Have to settle for where we are

The Mount, Edith Wharton’s country place, in Lenox, Mass., in The Berkshires. from when its construction was completed, in 1902, to when she left to live in France in 1911. It’s now a museum. Ms. Wharton knew the sad and impoverished aspects of The Berkshires, too, as you see her novella Ethan Frome.

“It was easy enough to despise the world, but decidedly difficult to find any other habitable region.

— Edith Wharton (1862-1937), American novelist.

A town in The Berkshires in 1884

A 'mystical and magical' land on Cape Ann

“Red Landscape #1, Dogtown,” (acrylic on canvas), by Ed Touchette, at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass. Gift of the artist, given in memory of Dana Todd.

The museum notes:

“The 3,000-acre swath of boulder-strewn land that makes up the center of Cape Ann has been known as Dogtown for generations. Since the disappearance of the last glacier, the area has undergone many iterations—from inhabitation by Native American groups and subsequently Colonial settlers to a sparse population of those on the fringes of society—and a slow but steady reversal of pasture lands back to the woodlands that are experienced in this protected green space today. Despite these changes, Dogtown remains mystical and magical, a sanctuary from its busier surroundings, a place for quiet thought and a reunion with nature. Read on as we explore its history and impact as a vast expanse of land that endures as both a resource and a challenge for the people of Cape Ann.’’

Chris Powell: ‘Baby bonds’ idea doesn't address need for crucial human capital

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut State Treasurer Shawn Wooden has brought to Connecticut a proposal that has been floating around the country for a few years now. Wooden would have state government endow "baby bonds" for poor children, opening $5,000 savings accounts for them at birth with the proceeds made available to them at age 18 for purposes including college education, home ownership, starting a business, or retirement savings.

The idea is pending as legislation in the General Assembly, and at a meeting in Waterbury last week Wooden argued that it would break down "structural racism." Such fashionable cant seems obligatory with many policy proposals these days, but it may be silliest as it tags along with "baby bonds," since their premise is that people are most disadvantaged not by racism at all but by poverty.

Good for the "baby bonds" idea at least for recognizing that much. But the proposal fails to recognize the primary cause of generational poverty. It is not racism or the lack of financial capital but rather the lack of human capital.

Most of the babies who would be targeted by "baby bonds" are born into homes without fathers around, and sometimes without mothers as well as they are left for a grandparent to raise. These children seldom have any mentors. Because of their lack of parenting and Connecticut's pernicious educational policy of social promotion, these children graduate from high school without having mastered even elementary school work. They are not prepared to be self-sufficient adults, much less to start and operate a business with "baby bond" money -- and most new businesses fail anyway.

As for college, young people from poor minority households who have performed well in high school are likely to get scholarships for college anyway quite without having to rely on "baby bond" money, and if they perform well in college and have developed job skills, they will have no trouble getting hired by major corporations.

But throwing money at a problem seems to be the only solution of which liberalism is capable anymore.

Poverty, not racism, is the country's biggest problem and the biggest problem of racial minorities, and Connecticut's worst "structural racism" is that of its welfare and educational systems, which, far more for racial minorities than for whites, destroy families by subsidizing childbearing outside marriage and substituting self-esteem for learning.

xxx

As the General Assembly approaches legalizing and commercializing marijuana, Connecticut may be realizing that drug criminalization is futile. But meanwhile the legislature seems about to outlaw sale of flavored "vaping" fluids used with electronic cigarettes. So what gives?

The argument for the latter legislation is that most young people who use tobacco started with electronic cigarettes, which lure them with candy-store flavorings. True enough, perhaps, but then marijuana also is a "gateway" drug, an introduction to more addictive drugs like heroin, cocaine, and prescription painkillers.

Of course, alcoholic beverages long have been beyond the capacity of many people to handle, but outlawing them a century ago made the problem worse.

Decades of public-health campaigns have sharply reduced tobacco smoking. Unfortunately such campaigns against intoxicating drugs have not been successful. Many people crave intoxication, since life isn't so enjoyable for them. But "vaping" fluids don't intoxicate and have some benefit for people trying to break tobacco addiction.

If the attack on "vaping" products means to discourage tobacco smoking, young people who "vape" will run into the anti-tobacco campaigns eventually. Even before that they might encounter a parent or mentor and get some counseling about healthy living.

Besides, just as the ingredients for making alcoholic beverages remained legal and widely available during Prohibition, the ingredients for making "vaping" fluids are legal and will remain available too. The government won't be able to eliminate them much better than it has eliminated illegal drugs. Instead government mainly will run up the price and thereby enrich some clever entrepreneurs.

Government fairly enough can prohibit the sale to minors of goods that might endanger them. But a country that would be "the land of the free and the home of the brave" shouldn't treat adults like children.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester.

Learning and burning

“May memory restore again and again

The smallest color of the smallest day:

Time is the school in which we learn,

Time is the fire in which we burn.’’

— From “Calmly We Walk Through This April’s Day,’’ by Delmore Schwartz (1913-1966)

James T. Brett: Pell Grants should be doubled

BOSTON

College affordability and access to higher education has been a topic of much discussion in Washington, D.C., and throughout our region in recent years. And rightfully so. The price of higher education continues to increase, and millions of Americans struggle with student loan debt. At the same time, a college degree is for so many a path to career success and financial security, and our region’s employers depend on a talented pipeline of highly skilled workers to continue to grow and thrive.

One important step Congress could take in the immediate future to help make a college degree more affordable and accessible to students is to increase the maximum grant amount under the federal Pell Grant program. In fact, the New England Council—the nation’s oldest regional business association—is calling on Congress to double the maximum Pell Grant amount.

Earlier this month, NEBHE and several New England higher ed leaders and organizations asked Congress to double the Pell Grant maximum to $12,990 by the 2021-22 academic year and ensure that the increase is permanent by making the increased portion of the grant an entitlement. Read NEBHE’s letter to Congress here.

Pell Grants were established by Congress in 1972 and named in honor of the late U.S. Sen. Claiborne Pell, of Rhode Island. The grants are financial awards provided to low-income students to pursue undergraduate degrees. The program is a vital tool to ensure that low-income students–many of whom are “first-generation,” that is, the first in their immediate families to attend college–are able to pursue their undergraduate education. It is the largest source of federal funding for students pursuing post-secondary education.

For the 2021-22 award year, the maximum Pell Grant award is $6,495, not nearly enough to cover the average cost of tuition and fees for the 2020-21 academic year. The maximum Pell Grant amount has increased only in increments of $150 over the past several years—certainly not keeping pace with tuition increases and inflation. In 1975, the Pell Grant covered almost 80 percent of tuition and room and board at a four-year public college, compared with less than 60 percent today.

Doubling the maximum Pell Grant amount would enable more low-income students to pursue higher education and incur less debt. Further, an increase in the maximum Pell Grant amount would help address racial inequities in higher education. For example, according to the U.S. Department of Education, over 57 percent of African American undergraduate students received Pell Grants during the 2015-16 academic year, compared with 32 percent of white undergraduates during the same period.

There is significant support across the U.S. for doubling the Pell Grant. The New England Council is proud to join a growing list of respected national higher education associations in advocating for this change, including the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities and the American Council on Education. More than 900 colleges around the country recently signed on to a letter advocating for doubling the Pell Grant, including many here in New England.

As the federal Pell Grant program approaches its 50th anniversary next year, we cannot think of a better way to honor the legacy of this program and recognize the importance of ensuring access to higher education for all students than by doubling the maximum grant amount. We hope that our leaders on Capitol Hill will come together to take this important step, as it would truly be an investment in America’s future.

James T. Brett is president and CEO of the New England Council, a regional alliance of businesses, nonprofit organizations, and health and educational institutions dedicated to supporting economic growth and quality of life in New England.

In the Connecticut River Valley in Massachusetts. The valley is well known for the colleges up and down the valley. New England’s world-famous higher-education complex of big research universities, small liberal-arts colleges and specialized institutions comprise one of its biggest industries.

Ebb and flow

“Each Piece is Different’’ (acrylic on canvas), by Charlie Bluett, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

Charlie Bluett’s studio is in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont. He was born in England and educated at Eton College there, and has exhibited extensively in the United Kingdom and the United States.

The gallery says:

“Bluett is an abstract painter who is inspired by the ebb and flow of the natural processes of the earth. Using this as his reference, his interest is then in the process of building form, color, and surface texture into large scale compositions that are bold and dynamic, but also subtle in their shifting shapes and tones. His works contain elements that pay homage to the techniques of the old masters, blended with abstract expressionism and the colorfield painting of the contemporary names of our time.’’

Panoramic view of Willoughby Notch and Mount Pisgah, in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont.

— Photo by Patmac13

Todd McLeish: Surprises in book about two water-loving insect groups

Dragonflies

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Those curious about dragonflies and damselflies — the colorful, predatory aerialists seen at nearly every pond, lake, stream and river in summer — now have a new source of information about the numerous species found in Rhode Island.

Virginia “Ginger” Brown, the state’s leading dragonfly expert, recently authored and published a book called Dragonflies and Damselflies of Rhode Island. The book will help readers learn about the natural history, distribution and abundance of the state’s 139 species of odonates, the insect order that includes dragonflies and damselflies. The book was published in February by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Fish and Wildlife, its third volume about local wildlife.

“The book is designed for beginning naturalists, experienced naturalists, conservation groups, and just about anybody with an interest in the outdoors, like fishermen who see dragonflies when they’re fishing,” said Brown, a resident of Barrington who also wrote The Dragonflies and Damselflies of Cape Cod, in 1991. “It’s not something you’re going to carry with you in the field, but it’s a reference to help you identify and learn about every dragonfly and damselfly in Rhode Island.”

The 384-page book features profiles of each species, including habitat characteristics, range, behaviors, dates when they are active locally, and a map indicating where they have been observed. All of the illustrations are by artist and entomologist Nina Briggs, of Wakefield.

Most of the data for the book was collected between 1998 and 2004, when Brown organized an extensive citizen science project that culminated with the publication of the “Rhode Island Odonata Atlas,” a statewide inventory of dragonflies and damselflies. About 70 volunteers participated in the creation of the atlas, visiting more than 1,100 ponds, lakes, streams, rivers, and other sites in every community in the state to document as many species as they could find. More than 13,000 specimens were collected and identified.

“A large amount of what we know about odonates in Rhode Island was generated by those volunteers, many who had no experience with insects before,” said Brown, a biologist who used to work for the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. “I didn’t know how much they would be able to do and how many records they would produce, and I didn’t know if they would like getting up to their knees in the muck or how successful they’d be at swinging at net to catch them. It was so much fun to work with all of those people.”

Among the findings highlighted in the book was the discovery of several species never before recorded in New England, including the southern sprite and coppery emerald, both of which are southern species that Brown didn’t expect to find in the Ocean State. A species from the far north, the crimson-ringed whiteface, was also a surprise discovery.

Another new species for Rhode Island, the unicorn clubtail, turned out to be much more common than anyone imagined.

“We ended up finding it at 60 sites in all five counties in the state, making it a pretty ubiquitous critter,” Brown said. “It’s something that occurs in ponds without a lot of vegetation, a habitat that doesn’t look particularly intriguing and that may not have a lot of other species in them. It’s a new record for the state, but it turned out to be in 26 towns.”

Brown was especially pleased with the variety of dragonfly and damselfly species found throughout the state, and was surprised to find high diversity at unlikely places, such as the Blackstone River.

Overall, more than 100 species were recorded in five communities, and at least 90 species were found in an additional seven communities.

Not all of the data for Brown’s book came from the atlas project. Brown and several other entomologists collected some data independently in the years prior to the atlas, and additional information was added while the book was being written and designed.

After the “Rhode Island Odonata Atlas” was completed, the scientists concluded that a damselfly called the northern spreadwing was actually two different species, so Brown had to sort through her records to determine which of the two species were represented at the Rhode Island sites where they were found. And when an unexpected species called the Allegheny river cruiser turned up in Connecticut, she sorted through her records again to see whether any of the Rhode Island records of a very similar species, the swift river cruiser, were misidentified.

“That’s when I learned to never make assumptions,” Brown said.

With her latest book finally completed, Brown is planning to revisit some sites to confirm that some of the rarer species are still in the waterbodies where they were initially found.

“We’ve had some population loss going on, so we need to get back to check on species of greatest conservation need,” she said. “The 2010 floods knocked out some small dams, which drained some ponds, and that might be the reason for some of these losses. With more extreme rainfall events associated with climate change, we could have more ruptured dams and more population losses.”

Damselfly

Dragonflies and Damselflies of Rhode Island is available for $25, which includes shipping, and can be bought by emailing DEM.DFW@dem.ri.gov.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Dedicate your life

‘Status-seeking has to be fought anew in every generation. The dedicated life is the life worth living. You must give with your whole heart.’’

— Annie Dillard (born 1945), Pulitzer Prize-winning fiction and nonfiction author. She spends part of the year in Wellfleet, on outer Cape Cod.

Looking toward Wellfleet Harbor from over the town’s elementary school

— Photo by Achituv

Smith’s 'meditations on land, water and air'

“Stream No. 31” (chromogenic print), by British-born (but now of Brooklyn) photographer Jonathan Smith, in his show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through May 23.

The gallery says:

Jonathan Smith spent the early years of his career assisting and printing for the renowned photographer Joel Meyerowitz {famous for his photos of Cape Cod}, and has had solo exhibitions in both nationally and internationally. His work consists of large-scale, highly nuanced color photographs of the stark natural beauty and inherent impermanence of landscapes.

“Smith has been photographing natural landscapes for more than 15 years. Shooting precisely and selectively with incredible detail, often revisiting the same site on several occasions until he feels the essential character of the landscape has been revealed to him. This conscious and gradual process of documentation results in meditations on land, water and air.’’

His investigations of landscape have led him to the remote locations of northern Iceland and southern Patagonia, where he photographed streams, glaciers, glacial rivers and waterfalls. These landscapes, devoid of human presence, display a world lost in time. Often abstracted, these photographs of mountain streams and glacial shifts are a reminder of the forces of nature at play; a sublime beauty far removed from the everyday. Drifting into frame, the dreamlike palette of these landscapes offers a window into an ephemeral world where scale and perspective become impalpable. These landscapes inspired the creation of large-scale prints that echo the vastness of the spaces they depict, inviting the viewer in to contemplate their own relationship to the natural world.

Above: Stream No. 31, chromogenic print, available sizes: 30x37.5" ed. of 8, 40x50" ed. of 5, 56x70" ed. of 3

Rachel Bluth: After a year of motorized mayhem, Mass., Conn., R.I., other states consider crackdowns

“American Landscape’’ (graphite on Strathmore rag, 1974), by Jan A. Nelson

See news on this topic from Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut below.

As more Americans start commuting to work and hitting the roads after a year indoors, they’ll be returning to streets that have gotten deadlier.

Last year, an estimated 42,000 people died in motor-vehicle crashes and 4.8 million were injured. That represents a 8 percent rise from 2019, the largest year-over-year increase in nearly a century — even though the number of miles driven fell by 13 percent, according to the National Safety Council.

The emptier roads led to more speeding, which led to more fatalities, said Leah Shahum, executive director of the Vision Zero Network, a nonprofit organization that works on reducing traffic deaths. Ironically, congested traffic, the bane of car commuters everywhere, had been keeping people safer before the pandemic, Shahum said.

“This is a nationwide public health crisis,” said Laura Friedman, a California Assembly member who introduced a bill this year to reduce speed limits. “If we had 42,000 people dying every year in plane crashes, we would do a lot more about it, and yet we seem to have accepted this as collateral damage.”

California and other states are grappling with how to reduce traffic deaths, a problem that has worsened over the past 10 years but gained urgency since the onset of the covid-19 pandemic. Lawmakers from coast to coast have introduced dozens of bills to lower speed limits, set up speed camera programs and promote pedestrian safety.

The proposals reflect shifting perspectives on how to manage traffic. Increasingly, transportation safety advocates and traffic engineers are calling for roads that get drivers where they’re going safely rather than as fast as possible.

Lawmakers are listening, though it’s too soon to tell which of the bills across the country will eventually become law, said Douglas Shinkle, who directs the transportation program at the National Conference of State Legislatures. But some trends are starting to emerge.

Some states want to boost the authority of localities to regulate traffic in their communities, such as giving cities and counties more control over speed limits, as legislators have proposed in Michigan, Nebraska and other states. Some want to let communities use speed cameras, which is under consideration in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Florida and elsewhere.

Connecticut is considering a pedestrian safety bill that incorporates multiple concepts, including giving localities greater authority to lower speeds, and letting some municipalities test speed cameras around schools, hospitals and work zones.

“For decades really we’ve been building roads and highways that are suitable and somewhat safe for motorists,” said Connecticut state Sen. Will Haskell (D.-Westport), who chairs the committee overseeing the bill. “We also have to recognize that some people in the state don’t own a car, and they have a right to move safely throughout their community.”

A huge jump in road fatalities started showing up in the data “almost immediately” after the start of the pandemic, despite lockdown orders that kept people home and reduced the number of drivers on the road, said Tara Leystra, the National Safety Council’s state government affairs manager.

“A lot of states are trying to give more flexibility to local communities so they can lower their speed limits,” Leystra said. “It’s a trend that started before the pandemic, but I think it really accelerated this year.”

In California, citations issued by the state highway patrol for speeding over 100 miles per hour roughly doubled to 31,600 during the pandemic’s first year.

Friedman, a Democrat from Burbank, wants to reform how California sets speed limits on local roads.

California uses something called the “85th percentile” method, a decades-old federal standard many states are trying to move away from. Every 10 years, state engineers survey a stretch of road to see how fast people are driving. Then they base the speed limit on the 85th percentile of that speed, or how fast 85% of drivers are going.

That encourages “speed creep,” said Friedman, who chairs the state Assembly’s transportation committee. “Every time a survey is done, a lot of cities are forced to raise speed limits because people are driving faster and faster and faster,” she said.

Even before the pandemic, a California task force had recommended letting cities have more flexibility to set their speed limits, and a federal report found the 85th percentile rule similarly inadequate to set speeds. But opposition to the rule is not universal. In New Jersey, for instance, lawmakers introduced a bill this legislative session to start using it.

Friedman’s bill, AB 43, would allow local authorities to set some speed limits without using the 85th percentile method. It would require traffic surveyors to consider areas like work zones, schools and senior centers, where vulnerable people may be using the road, when setting speed limits.

In addition to lowering speed limits, lawmakers also want to better enforce them. In California, two bills would reverse the state’s ban on automated speed enforcement by allowing cities to start speed camera pilot programs in places like work zones, on particularly dangerous streets and around schools.

But after a year of intense scrutiny on equity — both in public health and in law enforcement — lawmakers acknowledge they need to strike a delicate balance between protecting at-risk communities and overpolicing them.

Though speed cameras don’t discriminate by skin color, bias can still enter the equation: Wealthier areas frequently have narrow streets and walkable sidewalks, while lower-income ones are often crisscrossed by freeways. Putting cameras only on the most dangerous streets could mean they end up mostly in low-income areas, Shahum said.

“It tracks right back to street design,” she said. “Over and over again, these have been neighborhoods that have been underinvested in.”

Assembly member David Chiu (D.-San Francisco), author of one of the bills, said the measure includes safeguards to make the speed camera program fair. It would cap fees at $125, with a sliding scale for low-income drivers, and make violations civil offenses, not criminal.

“We know something has to be done, because traditional policing on speed has not succeeded,” Chiu said. “At the same time, it’s well documented that drivers of color are much more likely to be pulled over.”

Rachel Bluth is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Nontheological reclusion

Saint Jerome, who lived as a hermit near Bethlehem, depicted in his study being visited by two angels (Cavarozzi, early 17th Century).

“The peculiarity of the New England hermit has not been his desire to get near to God but his anxiety to get away from man.’’

— Hamilton Wright Mabie (1845-1916), American essayist, editor, critic and lecturer

May be washable if not edible

“Fiberglass sphere” (sculpture), by Brunswick, Maine-based William Zingaro, at the Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine.

The south end of Wells Beach. How long will those houses last?

One of Wells’s one-room schoolhouses, built in the 19th Century.

— Photo by BMRR