‘To buffer the passage of time’

Center field bleachers at Fenway Park during a 2014 game.

— Photo by Vegasjon

“[Baseball] breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings, and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall all alone. You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most, it stops.”

— A. Bartlett Giamatti (1938-1989), a lifelong Red Sox fan who served as president of Yale and baseball commissioner

1917 map of Fenway Park.

1919 rally at Fenway for Irish independence from Britain. Boston had a huge concentration of Irish-Americans.

Masculine material

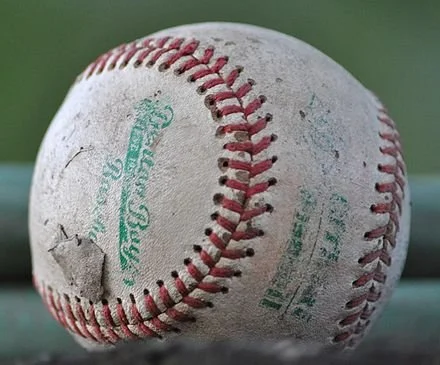

“Sharrod Hosten Study III” (archival ink on paper), by Kehinde Wiley, in the show “Masculine Identities: Filling in the Blank,’’ at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst Fine Arts Center through May 14.

The gallery says that the show explores masculinity and its place in art. “Featuring work by Carlos Villa, Andy Warhol, Kehinde Wiley and Nicole Eisenman, this exhibition aims to take the traditionally masculine traits of rigidity, roughness, strength and control and interpret them in new ways.’’

Llewellyn King: A shrug when it comes to mass murder with guns

AR-15-style assault rifle made by Southport, Conn.-based Sturm, Ruger & Co.

A Smith & Wesson AR-15-style assault rifle, designed to tear apart as many people as possible as fast as possible.

In Maryville, Tenn., where long -Springfield, Mass.-based gun maker Smith & Wesson’s is moving its headquarters. The company makes assault rifles beloved by mass murderers. That has bothered folks in Massachusetts but makes the company popular in gun-cult-dominated Tennessee and other violent Red States.

— Photo by Brian Stansberry

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Murder most foul,” cries the ghost of Hamlet’s father to explain his own killing in Shakespeare’s play.

We shudder in the United States when yet more children are slain by deranged shooters. Yet we are determined to keep a ready supply of AR-15-type assault rifles on hand to facilitate the crazy when the insanity seizes them.

The murder in Nashville of three nine-year-olds and three adults should have us at the barricades, yelling bloody murder. Enough! Never again!

But we have mustered a national shrug, concluding that nothing can be done.

Clearly, something can be done; something like reviving the assault rifle ban, which expired after 10 years of statistically proven success.

We are culpable. We think that our invented entitlement to own these weapons, designed for war, is a divine right, outdistancing reason, compassion, and any possible form of control.

The blame rests primarily on something in American exceptionalism that loves guns. I mostly understand that; I like them myself, as I write from time to time. I also like fast cars, small airplanes, strong drink, and other hair-raising things.

But society has said these need controls — from speed limits to flying instruction — and has severe penalties for mixing the first two with the last. Those controls make sense. We abide by them.

When it comes to that other great national indulgence, guns, society has said safety doesn’t count. So far this year, more than 10,000 people have been killed in gun violence. If that were the number of fatalities from disease, we would again be in lockdown.

We have concocted this scared right to keep and use guns. To ensure this, the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution has been manhandled by lawyers into being a justification for putting something deadly out of the reach of social control or even rudimentary discipline.

The latest school shooting has raised our hackles, but not our capacity to act. This national shrug at something which can be fixed is a stain on the body politic.

Most of the conservative wing of the establishment, represented by the Republican Party, has dismissed it as one might a natural disaster.

But the routine murder of innocents in school shootings is a man-made disaster. Worse, it is sanctified by a particular interpretation of the Second Amendment.

It is an interpretation which has demanded, and continues to demand, legal contortionism. This is used to justify the citizenry owning and using weapons of war.

This latest school shooting, which happened in this young year, was shocking, but what was more shocking was the political reaction.

President Biden wrung his hands and said nothing could be done without the support of Congress — thus endorsing a national fatalism.

Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina suggested more policemen in schools, and Rep. Thomas Massie (R.-Tenn.) said teachers needed to be armed. His children are homeschooled.

In personal life and in national life perceived impossibility is hugely debilitating.

Imagine if the Founding Fathers had said the British Empire was too strong to challenge, if FDR had said America couldn’t rise against the forces of the economic chaos of the 1930s, or if Margaret Thatcher had said British trade unions were too strong to be opposed?

These are incidents where perceived reality was, with struggle, trounced for the general good.

Guns along with drugs are the largest killer of young people. They aren’t unrelated. Unregulated guns find their way to the drug gangs of Central America, facilitating the flow of drugs.

On the Senate floor, the chamber’s longtime chaplain, retired Rear Adm. Barry C. Black, took on the pusillanimous members of his flock after the Nashville murders, quoting the 18th-century Anglo-Irish statesman Edmund Burke’s admonition, “The only thing needed for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.” Indubitably.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

A whimsical world

“Flatland From Can You See What I See?: Hidden Wonders!” (pigmented inkjet photo), by Walter Wick, at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, through Sept. 3.

The museum explains:

“The whimsical world of Walter Wick has fascinated people of all ages since 1991, when his first children’s book series I SPY found its way onto the bookshelves of millions of American households. The success of Wick’s books has established him as one of the most celebrated photographic illustrators of all time. A Hartford native, Wick began his artistic career as a landscape photographer before becoming enamored with the technical aspects of studio photography. Wick aspired to master studio techniques, but also to represent such concepts as the perception of space and time in photographs, and experimented with mirrors, time exposures, photo composites, and other tricks to do so. This manipulation of processes and perception has led to a prolific career that has now, over 30 years after the release of I SPY: A Book of Picture Riddles, resulted in the publication of more than 26 children’s books.’’

Ripen, then leave

Victorian-era row houses in Springfield, built in the city’s industrial heyday.

“Springfield, Massachusetts, is a place to be from. Talented people ripen in Springfield, then move away to larger cities to make their fortune.’’ (Like Theodor Geisel, the Springfield native later known as Dr. Seuss.)

— James C. O’Connell, in Pioneer Valley Reader (1995)

David Warsh: Read and reread Kindleberger, with his grasshopper intellect

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Most people know economist Charles. P. Kindleberger, to the extent they know him at all, as the author of Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, (Basic Books, 1978), the best book on its topic since Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, by Walter Bagehot, in 1873. Fewer understand that the reason that they know Hyman Minsky at all is because Kindleberger devoted the second chapter of his book to him.

Though Minsky was “a man with a reputation among monetary theorists for being particularly pessimistic, even lugubrious, in his emphasis on the fragility of the monetary system and its propensity to disaster… his model lends itself effectively to the interpretation of economic and financial history,” wrote Kindleberger. After that, Minsky became for some a shadow Keynes.

In fact Minsky didn’t really have a model, in the sense the term was used by macroeconomists. Like Kindleberger, he was mostly a literary economist in possession of a narrative, but he was ten years younger and a member of the post-WWII generation. After completing his Ph.D. at Harvard University in 1949, Minsky had taught ten years at Brown University, eight more at University of California at Berkeley and another twenty-five at Washington University in St. Louis before retiring, in 1990. He was, however, one of a relative handful of scholars who took financial intermediation seriously. He published “Central Banking and Money Market Changes,” in the Quarterly Journal of Economics in 1957 and Stabilizing an Unstable Economy (Yale), in 1986. But he never gained altitude in the profession and settled instead for the lesser role of “maverick.” He died in 1996.

CPK, as he was known, on the other hand, was a star, though of lesser magnitude in a Massachusetts Institute of Technology department led by Nobel laureates Paul Samuelson, Robert Solow and Franco Modigliani. Known initially mostly as a textbook writer, Kindleberger’s influence as an international economist grew until he became a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association, in 1980, and president in 1985. He died in 2003, but Manias, Panics and Crashes has outlived him, though three posthumous editions edited by Robert Aliber, who somewhat broadened its scope. Robert McCauley has edited an eighth.

Now an important new biography has appeared. Money and Empire: Charles P. Kindleberger and the Dollar System (Cambridge, 2022), by Perry Mehrling, of Boston University, brings CPK vividly back to life, in the form of a coming-of-age story about an unusually perspicacious young man’s adventures in the last days of literary economics. The author, Mehrling, is something of a border-crosser himself, an economic biographer who first book, The Money Interest and The Public Interest: American Monetary Thought 1920-1970 (Harvard 1997) profiled economists Allyn Young, Alvin Hansen and Edward Stone Shaw. His Fischer Black and the Revolutionary Idea of Finance (Wiley, 2005) traced the intellectual development and personal life of the co-inventor of the Black-Scholes options pricing formula – “a charming and brilliant book about a charming and brilliant man,” according to Robert Lucas.

Money and Empire is Mehrling’s fourth book. Kindleberger’s serial lives and ideas turn out to have been no less interesting than those of Black. Born to WASPy parents in New York City in 1910, “Charlie” – that’s what nearly everyone called him – attended the Kent School, a boarding school in rural Connecticut, and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. His father, a prosperous lawyer, had hoped that his only son would become a lawyer, but Charlie spent his summers at sea, sailing around Europe as a merchant seaman.

By then the Great Depression was on. So it was at Columbia University that Kindleberger became an economist, studying under H. Parker Willis, one of the architects of the Federal Reserve System. He then worked as a central banker, from 1936 until 1942; first at the New York Fed; then the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland; finally with the Fed’s Board of Governors in Washington. After America entered World War II, he joined the Office of Strategic Services in London, and became chief of its Enemy Objectives Unit in 1943. After the war, he spent three years at the State Department, working for William Clayton, on developing the Marshall Plan.

Disaster struck in 1948: in the early stage of the McCarthy era, Kindleberger’s security clearance was questioned by the FBI, apparently for remaining in touch with those with whom he had disagreed during negotiations surrounding the Bretton Woods treaty, in 1944. In 1951 it was vacated altogether. The path he had envisaged – civil service, central banking, government work – was foreclosed. The alternative was academia. He accepted an offer from the department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and left the State Department, in 1948.

The rest of Mehrling book is no less dramatic for tracing Kindlebeger’s intellectual engagement in the pressing issues of the day. How would New York and the dollar replace London and the pound sterling as the currency in which global trading would be conducted? There may be no better way for the lay person to follow this complicated story as it unfolded than through the life story of one of its foremost analytic protagonists. Mehring’s grace is extraordinary as he sifts through the reams of Kindleberger’s published books and articles; his private papers, now deposited in archives; and still more revealing family records. Mehrling’s insight is even more striking.

It turns out Kindlebeger’s most important book may have been nearly his last – A Financial History of Western Europe, nearly half of which is devoted to the interwar period and the years after World War II. Ostensibly notes for two courses that Kindleberger taught at the end of the Seventies – the first at the University of Texas at Austin, at the behest of his OSS friend Walt Rostow, the second at MIT – the book is, in Kindleberger’s own phrase, his chef d’oeuvre, an exposition of how the dollar system arose, what it is, and and how it is supposed to work, plus the background necessary to understand it.

There is just one problem. CPK described himself as a grasshopper intellect, hopping from topic to topic. His style is epigrammatic, even telegraphic. Mehrling tries to fill in the outlines of Kindleberger’s fundamentally institutionalist views; as author, though, he is too faithful to the story of his subject’s life to interpose his own opinions more than lightly.

Hence the dual purpose. With one jobs done, another looms. Mehrling’s third book, The New Lombard Street: How the Fed Became the Dealer of Last Resort (Princeton, 2011), was written quickly, in the aftermath of the crisis of 2007-08. Although it was better than almost all of the other analyses tumbling from the presses in those days, it still didn’t quite work. Mehrling’s others books each took most of a decade to write.

It is time now, to settle down to write one more. What are Mehrling’s own views on the prospects for the dollar system in the future of a world increasingly taking sides between the regnant American system and its rival now being gradually assembled in China? If this sort of thing interests, if you want to learn something about international economics up close and personal, then you can’t do better to pass the time than to read Money and Empire: Charles P. Kindleberger and the Dollar System.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Just before or after the greening?

Work by Rebecca Anne Nagle, a Gloucester, Mass.-based artist.

Chris Powell: Teacher raises always fail to reduce poverty in Connecticut

The Truant's Log,” by Ralph Hedley (1899)

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Hardly a week passes without revealing more evidence that poverty is worsening in Connecticut.

As an emergency measure, all public school students in Connecticut are now eligible for free or discounted school lunches for the current school year. But this month it was reported that the number of students who would qualify under the old rules increased by 4% in the year ending last October. The number of students not able to speak English increased by 10%. These data points are the key measures of poverty used by state government for allocating state money to school systems.

Predictably enough, most of both increases involved children in Connecticut's ever-struggling cities.

While the number of state students qualifying for free school lunches had fallen in the prior two years, this seems to have been only because of the federal government's temporary tax credit for people with children. It's not that students suddenly were able to pay for their own lunches but that government was paying for them in a different way. The self-sufficiency of poor families did not increase.

People who consider themselves advocates for children assert that the new data calls for state government to "invest" another $300 million in education in the cities. Actually the new data suggest that state government's long practice of "investing" more in urban education has failed to achieve any substantial increase in learning or any substantial reduction in poverty.

But failure in education and poverty policy long has been the rationale for doing still more of what has failed.

All the extra money "invested" in urban education probably has failed because it has been spent mainly on increasing the compensation of teachers and administrators. The extra money has not made disadvantaged children any more prepared to learn when they get to school, nor has it made their households much less poor and their upbringings much better.

Indeed, though the virus epidemic is long over, chronic absenteeism in Connecticut's schools has risen to an average of 25% and is closer to 50% in the cities. Standardized test results show that student proficiency in Connecticut has been collapsing for more than 10 years. The education and poverty problems have endured no matter how much money has been thrown at them.

But for political reasons this failure of policy has never been audited.

This doesn't mean that teachers are to blame. They play the hand they are dealt -- indifferent, unparented and sometimes incorrigible students. School administrators who stick to such pernicious policies as social promotion and the suspension of discipline are partly to blame. But the problem is still bigger than that -- social disintegration and proletarianization, which begin long before children get to school, and quite without government's objection.

The legislation proposed by a few far-left Democrats in the General Assembly to require people to vote seems to presume this proletarianization -- to presume that the many people who don't vote and the many who don't even register to vote would vote Democratic if they were required to vote, since the Democrats are the party of enlarging government to dispense ever more free stuff and patronage and to increase dependence on government.

The mandatory-voting legislation raises questions that its advocates have yet to answer.

Could the mandatory voting requirement be met by filing a form affirming that a person is aware of an election but doesn't want to vote for anyone?

What would be the penalty for refusing to vote or to file the opt-out form?

Would mandatory voting apply to everyone or only to those people registered to vote?

Would a mandatory voting requirement discourage people from registering to vote in the first place?

Perhaps most important, why would requiring everyone to vote necessarily improve politics, government, and public life?

After all, for years now, half of Connecticut's high school graduates have failed to master high school math and English, most have lacked a basic knowledge of civics, and many carry this ignorance through life. They are being prepared mainly to become lifelong dependents of government.

Of course even the ignorant and uninformed have the right to vote. But why push it so hard?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

'Pulse of color, play of light'

“Rondo” (acrylic, graphite, cold wax and oil paint), by Lexington, Mass.-based artist Marina Thompson.

She writes:

“The pulse of color and the play of light and texture are constant sources of stimulation. Color creates light, light creates form. To generate depth, energy and movement with illusions of volume, space, light and time –

this is why I paint.’’

Town seal of Lexington, where the American Revolutionary War began in earnest.

Martha Bebinger: In Mass. and elsewhere, what next now that some roadblocks to addiction treatment are gone?

A 2007 assessment of harm from recreational drug use (mean physical harm and mean dependence liability): Buprenorphine was ranked 9th in dependence, 8th in physical harm, and 11th in social harm.

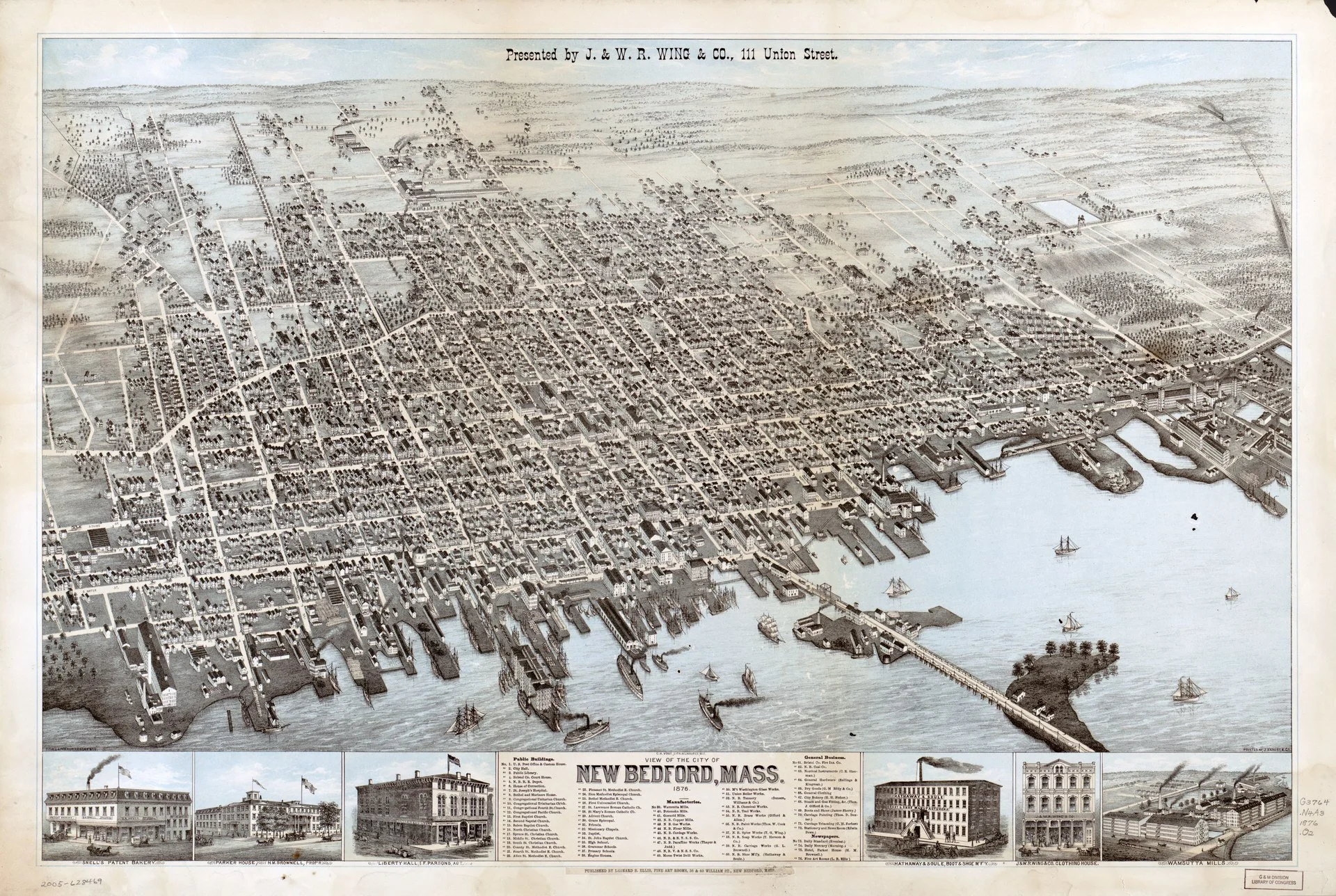

New Bedford in 1876, after the swift decline of the whaling industry as New Bedford became mostly a textile-manufacturing city, like its neighbor Fall River.

BOSTON

For two decades — as opioid overdose deaths rose steadily — the federal government limited access to buprenorphine, a medication that addiction experts consider the gold standard for treating patients with opioid use disorder. Study after study shows it helps people continue addiction treatment while reducing the risk of overdose and death.

Clinicians who wanted to prescribe the medicine had to complete an eight-hour training. They could treat only a limited number of patients and had to keep special records. They were given a Drug Enforcement Administration registration number starting with X, a designation many doctors say made them a target for drug-enforcement audits.

“Just the process associated with taking care of our patients with a substance use disorder made us feel like, ‘Boy, this is dangerous stuff,'” said Dr. Bobby Mukkamala, who chairs an American Medical Association task force addressing substance-use disorder.

“The science doesn’t support that but the rigamarole suggested that.”

That rigamarole is mostly gone. Congress eliminated what became known as the “X-waiver” in legislation President Joe Biden signed late last year. Now begins what some addiction experts are calling a “truth serum moment.”

Were the X-waiver and the burdens that came with it the real reason only about 7% of clinicians in the U.S. were cleared to prescribe buprenorphine? Or were they an excuse that masked hesitation about treating addiction, if not outright disdain for these patients?

There’s great optimism among some leaders in the field that getting rid of the X-waiver will expand access to buprenorphine and reduce overdoses. One study from 2021 shows taking buprenorphine or methadone, another opioid agonist treatment, reduces the mortality risk for people with opioid dependence by 50%. The medication is an opioid that produces much weaker effects than heroin or fentanyl and reduces cravings for those deadlier drugs.

The nation’s drug czar, Dr. Rahul Gupta, said getting rid of the X-waiver would ultimately prevent millions of deaths.

“The impact of this will be felt for years to come,” Gupta said. “It is a true historic change that, frankly, I could only dream of being possible.”

Gupta and others envision obstetricians prescribing buprenorphine to their pregnant patients, infectious disease doctors adding it to their medical toolbox, and lots more patients starting buprenorphine when they come to emergency rooms, primary-care clinics, and rehabilitation facilities.

We are “transforming the way we think to make every moment an opportunity to start this treatment and save someone’s life,” said Dr. Sarah Wakeman, the medical director for substance use disorder at Mass General Brigham, in Boston.

Wakeman said clinicians she has been contacting for the past decade are finally willing to consider treating patients with buprenorphine. Still, she knows stigma and discrimination could undermine efforts to help those who aren’t being served. In 2021, a national survey showed just 22% of people with opioid use disorder received medications such as buprenorphine and methadone.

The test of whether clinicians will step up and if prescribing will become more widespread is underway in hospitals and clinics across the country as patients struggling with addiction queue up for treatment. A woman named Kim, 65, is among them.

Kim’s recent visit to the Greater New Bedford Community Health Center, in southeastern Massachusetts, began in an exam room with Jamie Simmons, a registered nurse who runs the center’s addiction treatment program but doesn’t have prescribing powers. Kaiser Health News agreed to use only Kim’s first name to limit potential discrimination linked to her drug use.

Kim told Simmons that buprenorphine had helped her stay off heroin and avoid an overdose for nearly 20 years. Kim takes a medication called Suboxone, a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone, which comes in the form of thin, filmlike strips she dissolves under her tongue.

“It’s the best thing they could have ever come out with,” Kim said. “I don’t think I ever even had a desire to use heroin since I’ve been taking them.”

Buprenorphine can produce mild euphoria and slow breathing but there’s a ceiling on the effects. Patients like Kim may develop a tolerance and not experience any effects.

“I don’t get high on Suboxones,” Kim said. “They just keep me normal.”

Still, many clinicians have been hesitant to use buprenorphine — known as a partial opioid agonist — to treat an addiction to more deadly forms of the drug.

Kim’s primary-care doctor at the health center never applied for an X-waiver. So for years Kim bounced from one treatment program to another, seeking a prescription. During lapses in her access to buprenorphine, the cravings returned — an especially scary prospect after the powerful opioid fentanyl largely replaced heroin on the streets of Massachusetts, where Kim lives.

“I’ve seen so many people fall out in the last month,” Kim said, using a slang term for overdosing. “That stuff is so strong that within a couple minutes, boom.”

Because fentanyl can kill so quickly, the benefits of taking buprenorphine and other medications to treat opioid-use disorder have increased as deaths linked to even stronger types of fentanyl rise.

Buprenorphine is present in a small percentage of overdose deaths nationwide, 2.6%. Of those, 93% involved a mix of one or more other drugs, often benzodiazepines. Fentanyl is in 94% of overdose deaths in Massachusetts.

“Bottom line is, fentanyl kills people, buprenorphine doesn’t,” Simmons said.

That reality added urgency to Kim’s health center visit because Kim took her last Suboxone before arriving; her latest prescription had run out.

Cravings for heroin could have returned in about a day if she didn’t get more Suboxone. Simmons confirmed the dose and told Kim that her primary care doctor might be willing to renew the prescription now that the X-waiver is not required. But Dr. Than Win had some concerns after reviewing Kim’s most recent urine test. It showed traces of cocaine, fentanyl, marijuana, and Xanax, and Win said she was worried about how the street drugs might interact with buprenorphine.

“I don’t want my patients to die from an overdose,” Win said. “But I’m not comfortable with the fentanyl and a lot of narcotics in the system.”

Kim was adamant that she did not intentionally ingest fentanyl, saying it might have been in the cocaine she said her roommate shares occasionally. Kim said she takes the Xanax to sleep. Her drug use presents complications that many primary care doctors don’t have experience managing. Some clinicians are apprehensive about using an opioid to treat an addiction to opioids, despite compelling evidence that doing so can save patients’ lives.

Win was worried about writing her first prescription for Suboxone. But she agreed to help Kim stay on the medication.

“I wanted to start with someone a little bit easier,” Win said. “It’s hard for me; that’s the reality and truth.”

About half of the providers at the Greater New Bedford health center had an X-waiver when it was still required. Attributing some of the resistance to having the waiver to stigma or misunderstanding about addiction, Simmons urged doctors to treat addiction as they would any other disease.

“You wouldn’t not treat a diabetic; you wouldn’t not treat a patient who is hypertensive,” Simmons said. “People can’t control that they formed an addiction to an opiate, alcohol, or a benzo.”

Searching for Solutions to Soften Stigma

Although the restrictions on buprenorphine prescribing are no longer in place, Mukkamala said the perception created by the X-waiver lingers.

“That legacy of elevating this to a level of scrutiny and caution —that needs to be sort of walked back,” Mukkamala said. “That’s going to come from education.”

Mukkamala sees promise in the next generation of doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants coming out of schools that have added addiction training. The American Medical Association and the American Society of Addiction Medicine have online resources for clinicians who want to learn on their own.

Some of these resources may help fulfill a new training requirement for clinicians who prescribe buprenorphine and other controlled narcotics. It will take effect in June. The DEA has not issued details about the training.

But training alone may not shift behavior, as Rhode Island’s experience shows.

The number of Rhode Island practitioners approved to prescribe buprenorphine increased roughly threefold from 2016 to 2022 after the state said physicians in training should obtain an X-waiver. Still, having the option to prescribe buprenorphine “didn’t open the floodgates” for patients in need of treatment, said Dr. Jody Rich, an addiction specialist who teaches at Brown University. From 2016 to 2022, when the number of qualified prescribers increased, the number of patients taking buprenorphine also increased, but by a much smaller percentage.

“It all comes back to stigma,” Rich said.

He said long-standing resistance among some providers to treating addiction is shifting as younger people enter medicine. But tackling the opioid crisis can’t wait for a generational change, he said. To expand buprenorphine access now, states could use pharmacists, partnered with doctors, to help manage the care of more patients with opioid use disorder, Rich’s research shows.

Wakeman, at Mass General Brigham, said it might be time to hold clinicians who don’t provide addiction care accountable through quality measures tied to payments.

“We’re expected to care for patients with diabetes or to care for patients with heart attack in a certain way and the same should be true for patients with an opioid use disorder,” Wakeman said.

One quality measure to track could be how often prescribers start and continue buprenorphine treatment. Wakeman said it would help also if insurers reimbursed clinics for the cost of staff who aren’t traditional clinicians but are critical in addiction care, like recovery coaches and case managers.

Will Ending the X-Waiver Close Racial Gaps?

Wakeman and others are paying especially close attention to whether eliminating the X-waiver helps narrow racial gaps in buprenorphine treatment. The medication is much more commonly prescribed to white patients with private insurance or who can pay cash. But there are also stark differences by race at some health centers where most patients are on Medicaid and would seem to have equal access to the addiction treatment.

At the New Bedford health center, Black patients represent 15% of all patients but only 6% of those taking buprenorphine. For Hispanics, it is 30% to 23%. Most of the health center patients prescribed buprenorphine, 61%, are white, though white patients make up just 36% of patients overall.

Dr. Helena Hansen, who co-authored a book on race in the opioid epidemic, said access to buprenorphine doesn’t guarantee that patients will benefit from it.

“People are not able to stay on a lifesaving medication unless the immense instability in housing, employment, social supports — the very fabric of their communities — is addressed,” Hansen said. “That’s where we fall incredibly short in the United States.”

Hansen said expanding access to buprenorphine has helped reduce overdose deaths dramatically among all drug users in France, including those with low incomes and immigrants. There, patients with opioid use disorder are seen in their communities and offered a wide range of social services.

“Removing the X-waiver,” Hansen said, “is not in itself going to revolutionize the opioid overdose crisis in our country. We would need to do much more.”

This article is part of a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Martha Bebinger is a journalist with WBUR, in Boston

Those pesky barnacles

“A Mermaid” (1900), by John William Waterhouse

“It was a Maine lobster town —-

each morning boatloads of hands

pushed off for granite

quarries on the islands….

”One night you dreamed

you were a mermaid clinging to a wharf-pile,

and trying to pull

off the barnacles with your hands.’’

— From “Water,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977)

Loathing 'the immigrant swarms’

Immigrants from eastern and southern Europe arriving at Ellis Island, in New York City, in 1915.

Lovecraft’s gravestone in Providence’s beautiful Swan Point Cemetery.

“The ‘Howard’ in the entry had to be {horror, science-fiction and fantasy writer} Howard Phillips Lovecraft {1890-1937}, that twentieth-century puritanic Poe from Providence, with his regrettable but undeniable loathing of the immigrant swarms he felt were threatening the traditions and monuments of his beloved New England and the whole Eastern Seaboard.’’

― Fritz Leiber (1910-1992), American author of fantasy, horror and science- fiction tales, in Our Lady of Darkness

Big construction projects at Mass. colleges

Albert Sherman Center at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, in Worcester.

— Photo by Kjfoster93

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report

BOSTON

A variety of Massachusetts colleges and universities are undergoing major renovation projects. These include Bunker Hill Community College, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School and Endicott College.

This spring, MIT will be putting up projects to add more on-campus housing and additional buildings for interdisciplinary programs, including music and other arts. UMass Chan Medical School, in Worcester, will be investing $325 million in a building that will significantly increase the capacity for education and research, including clinical-trial therapeutics and animal medicine. Endicott College, in Beverly, received a $20 million donation from the Cummings Foundation for a new Cummings School of Nursing and Health Sciences building. Bunker Hill Community College will be constructing its first new building in a decade, set to open in 2025.

Where the (laconic) grandeur began

President Calvin Coolidge’s birthplace in bucolic Plymouth Notch, Vt.

“Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933) was the greatest man who ever came out of Plymouth Corner {actually Plymouth Notch} Vermont.’’

— Quote attributed to Clarence Darrow

Don’t let them know if you’re smiling

“She Who Wants the Rose Must Respect the Thorn’’ (fiber and mixed media), by Connecticut artist Norma Minkowitz, at the Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum’s show “Norma Minkowitz: Body to Soul,’’ through April 6.

— Photo courtesy of Fairfield University Art Museum

Trying to bridge two tribes

The Virginia-class attack submarine USS Missouri (SSN 780) heads towards the Thames River Bridge as it departs Naval Submarine Base New London for a scheduled deployment.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s a dispute possibly brewing between the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation, on the east side of the Thames River, in eastern Connecticut, and the Mohegan Tribal Nation, on the west side. Both tribes, best known for their huge casinos, want the river to have a Native American name rather than the English colonial one it has, named after the river that flows through London. (Thus there’s New London on the mouth of the waterway, much of which is an estuary.)

The Connecticut General Assembly is considering legislation to make the name more politically correct.

The Pequots want the river to be named, naturally, the Pequot River, a name used by early English colonists until they had it named the Thames in 1658.

But “In the spirit of cooperation, we have reached out to our neighbors at the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation in the hope of discussing a traditional name that would be agreeable to both of Connecticut’s federally recognized tribes,” said Charlie Strickland, chairman of the Mohegan Tribal Council of Elders.

This endless name changing is getting tedious. There’s apt to be pushback, as there has been in New York City since 2008, when the Triboro Bridge was renamed the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge. Most people still call it the Triboro.

Brigid Harrington: As high court decision looms, colleges search for alternatives to affirmative action

At Harvard’s campus, in Cambridge, Mass., the university’s seal.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

The U.S. Supreme Court may ban race-based affirmative action for college admissions this year. But that does not mean that schools will abandon their diversity goals.

As administrators wait for the high court to issue its final decision in two key affirmative-action cases, they are figuring out how they can continue to create the heterogenous campuses they want.

It is not an easy task. In an effort to increase racial diversity on campus, many colleges already have experimented with changing early action and legacy rules to no avail. “There is no replacement for being able to consider race,” Olufemi Ogundele, the University of California at Berkeley’s dean of admissions, recently told The Washington Post. “It just does not exist.”

Still, schools are searching for viable alternatives. The justices signaled during oral arguments last fall that they were ready to overturn their 19-year-old ruling that allowed race to be a factor in admissions decisions. Even back in 2003, the court maintained that race was not the ideal way to achieve diversity, saying racial preferences would no longer be necessary within 25 years.

In the two cases currently before the court, Students for Fair Admissions sued Harvard University as well as the University of North Carolina (UNC), arguing that it was unconstitutional to use race as part of the holistic admissions process. The court is expected to issue its ruling in June.

Judicial scholars expect that the court will make no distinction between public and private universities, banning affirmative action for nearly every school. Groups that filed amicus briefs in the current cases argued for two exceptions: for certain faith-basedschools, which say their mission is to help the historically disadvantaged, and for military academies, which contend that diversity in the officer corps is critical for military cohesion. It remains to be seen how, or if, the court will consider such exceptions.

The vast majority of colleges include diversity as part of their mission statements. But they will now need to engage in some deep soul-searching to decide what diversity really means to them. Do they want only students of different races on campus or do they really seek diversity of student viewpoints and life experiences?

To be sure, race – especially in America – influences a person’s life experience, and most colleges would agree that having students interact with classmates from other races in itself is valuable. But there are many other types of diversity, too, and schools may want to balance them all, including cultural, religious, geographic and socio-economic diversity.

Colleges that do not engage in race-based affirmative actions have tried a variety of approaches to achieve diversity based on socioeconomic and other factors. Texas launched an innovative model more than 20 years ago, later adopted by Florida and California schools, that guarantees students admission to its flagship public universities if they graduated in the top 10 percent of their high school classes. This “top 10 percent plan” quickly became controversial and has had mixed results. It boosted Hispanic enrollment at leading public universities, but not Black enrollment, according to an analysis by The Texas Tribune. The law had minimal effects on application rates from low-income high schools, other analyses found.

Another potential approach: ending early admission. These programs are used mostly by affluent students with access to savvy college counseling, who know it’s far easier to get into top-rated schools by applying early. But ending the practice may not make much difference unless a lot of schools agreed to simultaneously make such a change. Harvard University ended early admissions in 2007 for five years, urging other Ivy League schools to join them. But when no other colleges halted their programs, Harvard’s ability to attract historically disadvantaged students plummeted. Top minority students simply chose other Ivy League colleges. After five years, Harvard restarted its early-action program.

In their search for alternatives to race-based affirmative action, some colleges may consider eliminating legacy preference programs. Since the vast majority of legacies are Caucasian, some education experts view this practice as unfair and arcane. Top British universities, such as Oxford and Cambridge, ended legacy admissions long ago in the name of equity, but American university administrators have argued that the number of legacies is so small that it wouldn’t affect diversity much.

Colleges that have ended legacy admissions report vastly different experiences. The University of California schools did not improve their diversity by banning legacy admissions. But Johns Hopkins University, which stopped legacy preferences in 2014, has seen a substantial increase in minority enrollment in recent years. The number of undergraduate minorities jumped by more than 10 percentage points between 2009 and 2020, and now more than one-fourth of the university’s undergraduates are minorities.

There’s one key difference between Hopkins and the University of California schools: affirmative action. Unlike the University of California, Hopkins still considers race as a factor in admissions. If the Supreme Court rules that all colleges – including Hopkins – must be race-blind, it’s not clear whether banning legacy admissions would make much difference.

Some colleges are thinking about focusing on socio-economic diversity rather than race, which could wind up increasing the number of historically-disadvantaged minorities since many such students are low-income. But that could prove tricky, too. Outside of the rarefied world of Harvard and UNC, there are limits to how many students from low-income backgrounds some colleges can admit because of financial constraints. Many simply do not have enough scholarship money to offer to these applicants.

In a race-blind admissions world, colleges may need to resort to asking its applicants for help. If they require a new essay, asking students how they could contribute to diversity on campus, they may discover all kinds of new ways to create the educational melting pot they really want. It may be schools’ best hope.

Brigid Harrington is a lawyer at Bowditch & Dewey LLP a Massachusetts firm. Her practice focuses on issues facing institutions of higher education. Email: bharrington@bowditch.com.

‘Riotous threads’

“Wizard of Oz”, in by Janet Inman, in the show “Riotous Threads: Fiber Works from Gateway Arts,’’ at the Fuller Craft Museum, Brockton, Mass.

“Riotous Acts’’ encompasses work by artists with disabilities who work within the educational structure of Gateway Arts, in Brookline, Mass. The museum says that the show’s fiber art includes weaving, embroidery, thread collections and cloth doll making. “Embroidery dominates and colorful, thick thread and large needles help to make the designs bold and easy to understand.’’

David Warsh: Ukraine and Iraq

Pink shows extent of Russian occupation now.

Bodies of civilians shot by Russian soldiers lie on a street in Bucha, Ukraine The hands of one of the victims are tied behind his back.

—- Ukrinform TV

A children's hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine, after a Russian airstrike The city was mostly destroyed last year by Russian forces.

— Photo from armyinform.com.ua

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

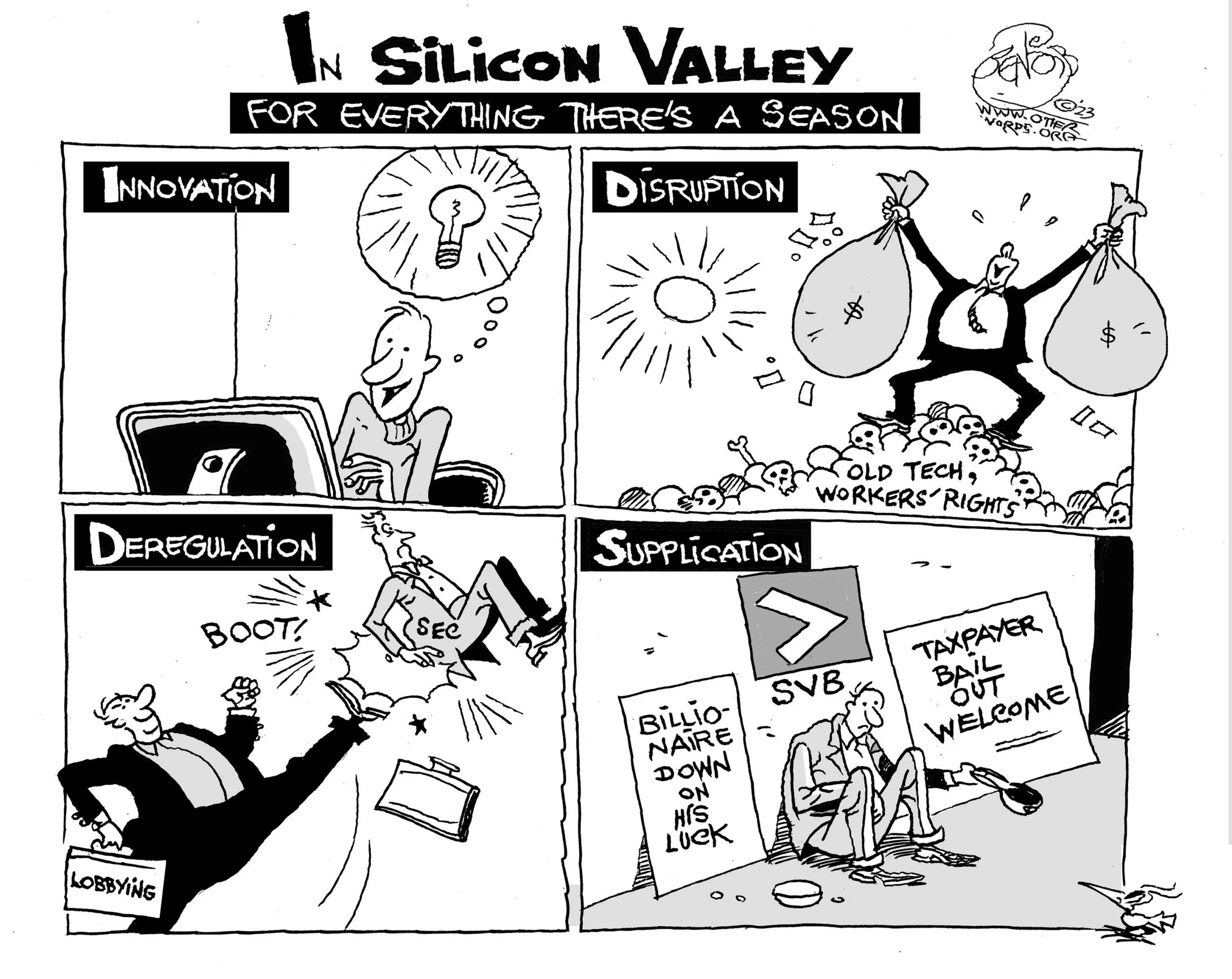

The failures of Silicon Valley and Signature banks were an addictive story these last few days. Humiliation for the start-up sector. Red meat for progressives. Field maneuvers for the financial press. A stress test for the bank-regulatory system, which failed, and for the Biden administration, which passed. It was not, however, the most important story of the week.

The bigger story was the news of the first shots fired in the battle that looms in next year’s presidential election over U.S.-led NATO support for Ukraine in its resistance to Russia’s invasion.

Protecting the independent nation from Russian absorption “is not a vital US interest,” said Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis in a statement to Fox News host Tucker Carlson last week. A quartet of Washington Post (and their editors) promptly jumped on the news. DeSantis’s position “firmly [put] the potential presidential candidate on the side of Donald Trump, and at odds with top Congressional Republicans.”

The presidential-contender continued,

“While the U.S. has many vital national interest – securing our borders, addressing the crisis of readiness with our military, achieving energy security and independence, and checking the economic, cultural, and military power of the Chinese Communist Party – becoming further entangled in a territorial dispute between Ukraine and Russia is not one of them.”

Two days later, the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal headlined “DeSantis’s First Big Mistake.” The two-term Florida governor enjoys a a reputation as “a fearless fighter for principle who ignores the polls,” the editorialists noted. “Then how to explain his puzzling surrender this week to the Trumpian temptation of American retreat?” The editorialists answered their own question before providing an out:

“The argument goes that Mr. DeSantis is reading the political mood. About 40 percent of Republicans say that the U.S. is providing “too much support” for Ukraine, up from 9 percent in March last year. Yet some of this is a function of polarized U.S.p olitics. Many Republicans oppose helping Ukraine because Mr. Biden is doing it, an the mirror image is Democrats from an anti-war left putting Ukrainian flag stickers on their electric cars…. Mr. DeSantis is clearly still refining his views and his remarks on Ukraine left some room to improve them later.”

The spectacle of the two American wings of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire disagreeing so sharply about a fundamental matter presage a far wider and more complicated battle next year.

I’ve criticized NATO enlargement for twenty-five years. I was therefore painfully conflicted by Vladimir Putin’s ham-handed invasion of Russian’s southern neighbor. It may have been understandable, but it was profoundly wrong. Still, I think of myself as center-left. How is it I now find myself allied with Tucker Carlson, Donald Trump, Ron DeSantis and Keri Lake?

I can only dream that they finally listened to me. Or, more likely than that, to Jeffrey Sachs, head of Columbia University’s Earth Institute, a long-time center-left maverick (see his “The Ninth Anniversary of the Ukrainian War;”, to veteran antiwar-journalist Seymour Hersh (“Who’s your George Ball?”; or even to film-maker Oliver Stone (“Ukraine on Fire”).

I don’t have poll numbers to show it, but my hunch is that something like 40 percent of all Democrats also have begun to believe that the U.S. is spending too much money or risk on Ukraine’s defense of itself, though President Biden and Senate leaders of both parties continue to strongly support the funding the war. DeSantis, like Trump, may suspect as much himself. He is an opportunist, as all politicians are, though less nimble than Trump.

I expect that Joe Biden and the Congressional leadership will have the advantage in 2024. I disagree with Biden’s foreign policy but I will vote for him if he runs again. Probably he will win – it won’t be easy for a Republican candidate to run on a call for retreat (never mind all the domestic issues!)

But a second term for the aging Biden would mean he will have to bear the burden if the defense of Ukraine ultimately fails. That depends on what happens on the battlefield, of course, where the advantages seems mostly to be Putin’s. When the war ends, political realignment in America will begin.

. xxx

Twenty years ago today, the morning of March 19, 2003, a U.S.-dominated coalition of forces began bombing Baghdad. The US had demanded that Saddam Hussein leave Iraq within 48 hours. When he didn’t, coalition forces attempted to kill him and his sons in the first hour of their “shock and awe” invasion. They didn’t succeed. President George W. Bush went on television that evening to describe the purpose the war to follow: “to disarm Iraq, to free its people, and to defend the world from grave danger.”

The invasion of Iraq was the fulcrum on which much has shifted since. In a speech to the Munich Conference on Security Policy, in February 2007, Vladimir Putin dissented sharply from Washington’s vision of a unipolar world and warned against further NATO expansion along Russia’s southern borders. It is worth noting that Putin borrowed heavily from the US playbook for his invasion of Ukraine last year, including the attempted decapitation of the Zelensky government leadership team.

It didn’t work any better in Kyiv than in Baghdad.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.