Kyle Sebastian Vitale: The campus courage crisis

The Yale Law School building, erected in 1931. Modeled after the English Inns of Court, the law building is at the heart of Yale's campus and contains a law library, a dining hall and a courtyard.

— Photo by Shmitra

Via The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Journal of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Courage has become a superlative attribute in our age. Health-care workers courageously work on the frontlines of COVID-19. Ukrainian President Zelensky exhibits courage against foes of democracy. These figures risk their personal security for the benefit of others and higher ideals. Higher education, too, is newly interested in courage as a centering ideal. That’s good: We need more courage on campus these days.

What we have instead is a mistaken notion of courage. Take recent events at Yale Law School. Student protesters disrupted a bi-partisan Federalist Society panel about religious freedoms, featuring the American Humanist Association and Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF). Students quietly joined the event before ambushing it, heckling the speakers Monica Miller and Kristen Waggoner over ADF’s and the Federalist Society’s conservative positions. As the video conveys, students acted under an assumed banner of courageous support for those identifying as transsexual.

Undoubtedly, this took nerve, and I am slow to fault students who intended to act in good faith. Yet is this courage? Most will agree that courage, while complex to define, carries a quality of personal sacrifice. Clemson University’s Cynthia Pury, speaking with the Berkeley Greater Good Science Center, helpfully qualifies courage as something requiring “a noble goal, personal risk and choice.” That seems to get at our common notion of courage as something that takes both strength and sacrifice.

The Yale event featured little personal risk. Students hid behind signs and cries that freedom of speech justified their actions. Missing was the vulnerability of actual discussion, and with it, the risk of one’s views undergoing scrutiny. This was about abolishing discomfiting views, not the small sacrifice of listening to others. Those who disagreed with speakers Miller or Waggoner but were prepared to listen, showed far more courage.

Similarly disruptive events occur across college campuses elsewhere, and they look the same: group settings, much shouting and swift departure by those protesting. Student hecklers rarely face up to the reality that they may not be entirely right or that their “enemy” may not be entirely wrong, both of which involve personal risk to one’s ideals. This is anger, but it is not courage. How do we counter this instinct?

By amplifying better models of courage. Emma Camp is one. Camp wrote recently about the culture of self-censorship among students at the University of Virginia. Students like Camp feel the relentless pressure to tow the ideological line, lest they find themselves on the outs with peers. Her essay is a model of courage, energized by higher ideals, open about her beliefs and honest about her mistakes. She knew the piece would receive a mixed response, and boy was she right, yet she met criticism with poise and interest.

If there are more students like Emma Camp out there, campus culture certainly doesn’t help us find them. A recent survey from Heterodox Academy reveals that 63 percent of students feel their campus climate prevents them from expressing their beliefs on various subjects, for fear of criticism or retribution from classmates and teachers. Courage’s unique ingredient—personal risk—is uniquely threatened on campus.

In response, higher education must create campuses rooted in trust and courage—trust that we are willing to hear each other out and courage to risk our assumptions and ideas. Students are certainly not blameless here, giving in to groupthink and pressuring one another into empty activism. Yet, they are also starved for models of courageous engagement with the uncomfortable. Numerous cases record campus administrators caving to students who demand more than they offer. Faculty too are often too quick to apologize when students perceive a racist or sexist comment, rather than respond with their intentions and pedagogical beliefs.

Courage is not screaming against the things that indispose us. Courage is sharing beliefs with confidence, authenticity and flexibility. It improves campus culture by contributing more perspectives and welcoming more views in the search for truth. It also requires much: faculty building classrooms that cultivate sincere interpersonal interest, administrators modeling charitableness and tenacity, and students choosing to listen and risk putting their beliefs under the microscope.

That same Heterodox Academy survey and other available research reveal that college students are more willing to share their beliefs in high-quality interactions with people they know. Our students are quietly ready to be more courageous on campus. Let’s support the ideals and the designs that help them get there.

Kyle Sebastian Vitale (@kylesebvitale) is director of programs at Heterodox Academy, a nonpartisan collaborative of more than 5,300 professors, educators, campus administrators, staff and students committed to enhancing the quality of research and education by promoting viewpoint diversity in higher education. He writes about higher education and has taught literature and pedagogy for over a decade at Yale University, the University of New Haven, the University of Delaware and Temple University.

Paintings from walks

“Riverway” (acrylic on canvas), by Robert Baart, in his show “Land Marks,’’ at M Fine Arts Galerie, Boston, through April 30.

The paintings in this collection result from the artist's pandemic walks from Brookline Village to his Ipswich Street, Boston, studio. The gallery says: "This recent body of work continues to emphasize the importance of nature in our lives. Regardless of location—city or countryside—the natural world we encounter has a direct effect on our health and spirit."

Washington Street in Brookline Village.

MIT spinoff seeks big new energy source via drilling very deep boreholes

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) statement

BOSTON

“A Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), spinoff company, Quaise Energy, is digging into the Earth to ease fossil-fuel reliance. MIT invests in startup technology companies, including Quaise Energy, using its fund and platform, called The Engine, to commercialize world-changing technologies.

“Quaise Energy has created new technology capable of digging some of the deepest boreholes in history to reach rocks below ground and surface a kind of heavy steam that has the potential to provide enormous quantities of energy, with a goal of using this steam to run power plants.

“To dig these holes, it will require the power of a laser to cut through dense rock, and it also needs to retain its intensity over long distances. This means as the technology goes further underground, it will have to maintain its power. Another advantage is that the lasers vitrify boreholes, meaning that their heat encases the blasted rock in glass and makes the holes less likely to collapse, which has been a significant problem in getting this type of energy when past companies have tried. There are other concerns that this team with the backing of MIT is working to resolve, including reducing the chances of seismic waves because of this.

“‘By drilling deeper, hotter, and faster than ever before possible, Quaise aspires to provide abundant and reliable clean energy for all humanity,’ said Carlos Araque, a former MIT student and employee, whose new company has raised $63 million to prove its technology. ‘This could provide a path to energy independence for every nation and enable a rapid transition off fossil fuels.’’’

Kelp: Great slippery aquaculture potential

In a kelp forest

— Photo by Ggerdel

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Growing the seaweed called kelp could become an important part of Rhode Island’s “blue economy’’ in coming years. So it was heartening to read, in ecoRI News, of the enthusiasm of Azure (birth name?) Cygler about her newish company, Rhody Wild Sea Garden LLC. She’s growing kelp in Narragansett Bay’s East Passage in water leased from an oyster farmer.

Kelp is great stuff – as a highly nutritious food, as a thickener and sweetener, for cosmetics and as a fertilizer. It is also a weapon in the battle against global warming: It absorbs carbon dioxide more effectively than do trees. And it takes in the excessive nutrients that wash into the water from chemical fertilizers (ah, those lawns and golf courses!) and other manmade stuff. Further, it’s harvested in the winter, and so less likely to draw the well-lawyered opposition of, say, affluent people with summer places along the shore.

Kelp in canned salad form

That gets me thinking about the University of Rhode Island’s Bay Campus, in Narragansett, home of URI’s internationally respected Graduate School of Oceanography. The Bay Campus needs major repairs and additions if the school is to continue to do the world-class research (with economic-development rewards from that) that, with teaching, is central to its mission.

Gov. Dan McKee has proposed a $50 million bond issue for improvements at the Bay Campus for voters to decide on next November. But URI says the full cost of the needed work is $157.5 million; there’s hope that state legislators will back a bigger amount than $50 million. They should: The School of Oceanography has a major part to play in the state’s future, environmentally, economically and otherwise. That includes defense, energy and, yes, aquaculture.

Rescuing objects; Singing Beach

“Orbs and a Blackbird’’ (encaustic), by Hollandra Berube, a Manchester-by-the-Sea (Mass.) artist.

She says:

“While creating my series Orbs and a Blackbird, I expressed my love of free form work and how I gravitate towards the sense of alignment with Self and just Being and Allowing. The boldness of Blackbird explores the feeling of one’s Higher-self overseeing all that IS; enlightenment and consciousness, and plays with my personal exploration of manifesting romantic energy, Love and balance.

“Brilliant color and bold ideas are hallmarks of my work as an artist, designer and builder. Nothing is off-limits and I move fluidly between mixed media, sculpture, encaustic, and interior design. I thrive on transforming empty spaces and combining the overlooked with the unexpected.

“Using encaustic paint and power tools, I rescue, revitalize, and reinterpret objects. Like an alchemist, creating something from nothing is the essence of my work. My deepest inspiration comes from being challenged by problem solving. I love responding to a particular situation and moving it from a negative to a positive. I rely on my desire for beauty, and my pleasure of aesthetic. My work envelopes the viewer in possibilities.’’

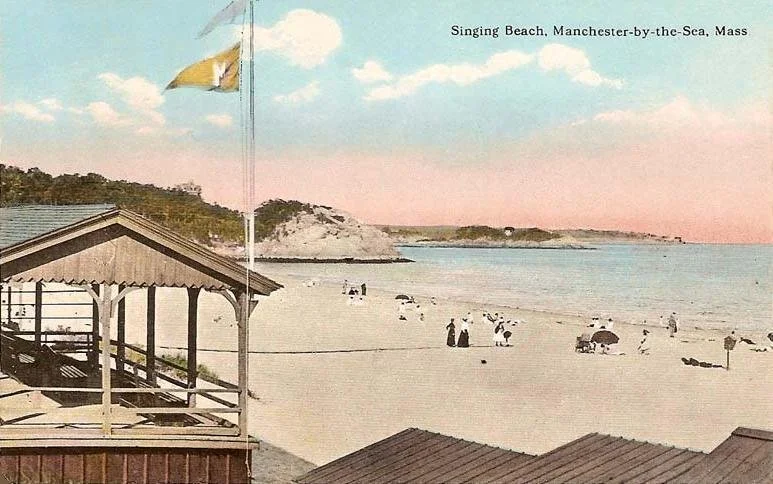

Singing Beach, in Manchester-by-the-Sea, in 1914. The strand, nearly three quarters of a mile long, is renowned for its fine white sand. When ocean bathing became popular in the late 19th Century, visitors discovered that the composition of the sand produces a “singing’’ sound when walked on.

‘To which we must return’

“It is mud season. God’s yearly reminder to us of the clay from which we rose and to which we must return, hill people and Commoners alike.’’

Howard Frank Mosher (1942-1917), novelist, in Where the Rivers Flow North. Virtually everything he wrote for publication was set in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, where he lived in Irasburg.

Panoramic view of Willoughby Notch and Mount Pisgah, in the Northeast Kingdom

— Photo by Patmac13

‘Into these hills’

In Franconia Notch in 1915. The northern part of Franconia Notch State Park is in the Town of Franconia.

”Because it is the work that is the work

you could take the world itself to mean

yourself. Into these hills you’ve taken for granite,

like the present, you could take place and be one

with the subject of your feeling arising

before you….’’

— “Tourist (Franconia {N.H.} 1986)’’, by Christopher Gilbert (1949-2007), American poet. He was an Alabama native who ended up as a Providence resident.

Melissa Bailey: West Nile Virus loves global warming

Global distribution of the West Nile Virus. There have been many cases in southern New England.

“West Nile Virus is a really important case study” of the connection between climate and health.

—Dr. Gaurab Basu, a primary-care physician and health-equity fellow at the Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment at Harvard’s public health school.

Michael Keasling, of Lakewood, Colo., was an electrician who loved big trucks, fast cars and Harley-Davidsons. He’d struggled with diabetes since he was a teenager, needing a kidney transplant from his sister to stay alive. He was already quite sick in August when he contracted West Nile Virus after being bitten by an infected mosquito.

Keasling spent three months in hospitals and rehab, then died on Nov. 11 at age 57 from complications of West Nile Virus and diabetes, according to his mother, Karen Freeman. She said she misses him terribly.

“I don’t think I can bear this,” Freeman said shortly after he died.

Spring rain, summer drought and heat created ideal conditions for mosquitoes to spread West Nile through Colorado last year, experts said. West Nile killed 11 people and caused 101 cases of neuroinvasive infections — those linked to serious illness such as meningitis or encephalitis — in Colorado in 2021, the highest numbers in 18 years.

The rise in cases may be a sign of what’s to come: As climate change brings more drought and pushes temperatures toward what is termed the “Goldilocks zone” for mosquitoes — not too hot, not too cold — scientists expect West Nile transmission to increase across the country.

“West Nile Virus is a really important case study” of the connection between climate and health, said Dr. Gaurab Basu, a primary-care physician and health-equity fellow at the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard’s public-health school.

Although most West Nile infections are mild, the virus is neuroinvasive in about 1 in 150 cases, causing serious illness that can lead to swelling in the brain or spinal cord, paralysis, or death, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People older than 50 and transplant patients like Keasling are at higher risk.

Over the past decade, the U.S. has seen an average of about 1,300 neuroinvasive West Nile cases each year. Basu saw his first one in Massachusetts several years ago, a 71-year-old patient who had swelling in his brain and severe cognitive impairment.

“That really brought home for me the human toll of mosquito-borne illnesses and made me reflect a lot upon the ways in which a warming planet will redistribute infectious diseases,” Basu said.

A rise in emerging infectious diseases “is one of our greatest challenges” globally, the result of increased human interaction with wildlife and “climatic changes creating new disease transmission patterns,” said a major United Nations climate report released Feb. 28. Changes in climate have already been identified as drivers of West Nile infections in southeastern Europe, the report noted.

The relationship between lack of rainfall and West Nile Virus is counterintuitive, said Sara Paull, a disease ecologist at the National Ecological Observatory Network in Boulder, Colo., who studied connections between climate factors and West Nile in the U.S. as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of California-Santa Cruz.

“The thing that was most important across the nation was drought,” she said. As drought intensifies, the percentage of infected mosquitoes goes up, she found in a 2017 study.

Why does drought matter? It has to do with birds, Paull said, since mosquitoes pick up the virus from infected birds before spreading it to humans. When the water supply is limited, birds congregate in greater numbers around water sources, making them easier targets for mosquitoes. Drought also may reduce bird reproduction, increasing the ratio of mosquitoes to birds and making each bird more vulnerable to bites and infection, Paull said. And research shows that when their stress hormones are elevated, birds are more likely to get infectious viral loads of West Nile.

A single year’s rise in cases can’t be attributed to climate change, since cases naturally fluctuate by year, in part due to cycles of immunity in humans and birds, Paull said. But we can expect cases to rise with climate change, she found.

Increased drought could nearly double the number of annual neuroinvasive West Nile cases across the country by the mid-21st Century, and triple it in areas of low human immunity, Paull’s research projected, compared with averages from 1999 to 2013.

Drought has become a major problem in the West. The Southwest endured an “unyielding, unprecedented, and costly drought” from January 2020 through August 2021, with the lowest precipitation on record since 1895 and the third-hottest daily average temperatures in that period, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration report found.

Spring rain, summer drought and heat created ideal conditions for mosquitoes to spread the West Nile virus throughout Colorado last year. West Nile killed 11 people and caused 101 cases of neuroinvasive infections in Colorado ― the highest numbers in 18 years.

“Exceptionally warm temperatures from human-caused warming” have made the Southwest more arid, and warm temperatures and drought will continue and increase without serious reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, the report said.

Ecologist Marta Shocket has studied how climate change may affect another important factor: the Goldilocks temperature. That’s the sweet spot at which it’s easiest for mosquitoes to spread a virus. For the three species of Culex mosquitoes that spread West Nile in North America, the Goldilocks temperature is 75 degrees Fahrenheit, Shocket found in her post-doctoral research at Stanford University and UCLA. It’s measured by the average temperature over the course of one day.

“Temperature has a really big impact on the way that mosquito-transmitted diseases are spread because mosquitoes are cold-blooded,” Shocket said. The outdoor temperature affects their metabolic rate, which “changes how fast they grow, how long they live, how frequently they bite people to get a meal. And all of those things impact the rate at which the disease is transmitted,” she said.

In a 2020 paper, Shocket found that 70 percent of people in the U.S. live in places where average summer temperatures are below the Goldilocks temperature, based on averages from 2001 to 2016. Climate change is expected to change that.

“We would expect West Nile transmission to increase in those areas as temperatures rise,” she said. “Overall, the effect of climate change on temperature should increase West Nile transmission across the U.S. even though it’s decreasing it in some places and increasing it and others.”

Janet McAllister, a research entomologist with the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, in Fort Collins, Colo., said climate change-influenced factors like drought could put people at greater risk for West Nile, but she cautioned against making firm predictions, since many factors are at play, including bird immunity.

Birds, mosquitoes, humans and the virus itself may adapt over time, she said. For instance, hotter temperatures may drive humans to spend more time indoors with air conditioning and less time outside getting bitten by insects, she said.

Climate factors like rainfall are complex, McAllister added: While mosquitoes do need water to breed, heavy rain can flush out breeding sites. And because the Culex mosquitoes that spread the virus live close to humans, they can usually get enough water from humans’ sprinklers and birdbaths to breed, even during a dry spring.

West Nile is preventable, she noted: The CDC suggests limiting outdoor activity during dusk and dawn, wearing long sleeves and bug repellent, repairing window screens, and draining standing water from places like birdbaths and discarded tires. Some local authorities also spray larvicide and insecticide.

“People have a role to play in protecting themselves from West Nile Virus,” McAllister said.

In the Denver suburbs, Freeman, 75, said she doesn’t know where her son got infected.

“The only thing I can think of, he has a house, they have a little baby swimming pool for the dogs to drink out of,” she said. “So maybe the mosquitoes were around that, I don’t know.”

Melissa Bailey is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Fine art to benefit Ukrainians

Left: work by Jennifer Okumura; middle: Vicki Kocher Paret; right: Nora Charney Rosenbaum

Artists at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, have come together to offer works for sale to benefit the Ukrainian people.

The gallery says:

“Let our degrees of hope and peace become legitimizing solidarity banners for Ukraine and 'anyone' who suffers in any corner of the world. A sense of unity reassures us that the world is a pleasant place underneath human complication. All profits are going toward Ukrainian relief.’’

David Warsh: Inflation: Cost push or too much money?

U.S. inflation 1910-2018.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

From the beginning, the thing that puzzled me was the way the experts talked past each other, or, more frequently, didn’t talk at all.

I explained last autumn how a magazine assignment in 1975 immersed me in the ‘70s debate about inflation and led me to 700-year index of wages and prices in England. An unreversed “price revolution” in the sixteenth century was its central feature. Immediately I had turned to rival experts on the period, both emeritus professors at the University of Chicago. As I wrote in November,

It turned out that the facts of the price revolution were well-established, and had been understood in a certain way since Jean Bodin, in 1556, first pointed to the influx of New World gold and silver.

Earl J. Hamilton (1899-1989) published “American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, 1501-1650’’; John Nef (1899-1988) had produced “The Rise of the British Coal industry’’, “Industry and Government in France and England 1540-1640,’’ and “War and Human Progress: an essay on the rise of industrial civilization.’’

Here were champions on opposing sides of the long-running argument about the price revolution. Some years later I learned that Joseph Schumpeter in his monumental History of Economic Analysis had characterized the difference of approach as between monetary and real analysis. I was dimly aware the gulf existed because I had began learning economics by reading two little books published in the 1920s, before John Maynard Keynes entered the debate: Money, by Sir Dennis Robertson, and Supply and Demand, by Hubert Henderson.

Schumpeter’s dichotomy was comforting because it periodized the controversy. Monetary analysis had thrived in the 17 and early 18th centuries, he had written; then, starting with Adam Smith, real analysis of supply and demand had eclipsed money for well over a century.

By 1975, the argument had again become front-page news. Inflation was surging. Why? Was the Federal Reserve Board imprudent in its conduct of monetary policy? Or were “cost-push” factors, OPEC price hikes and costs of its America’s Great Society and its Vietnam War forcing the hand of the Fed?

Alas, neither Hamilton nor Nef were of much use in writing about the issue in the present day. Both men had been born in 1899. Hamilton was a member of the university’s famous department of economics; Nef, a cultural historian. Only later did I come to understand what was implied by the distinction.

Hamilton had definitely won whatever debate existed between the two. As his department colleague Donald McCloskey wrote a few years later, “Various attempts to revise his history of prices (attaching it to population, for instance) have had difficulties with the sheer mass of evidence that Hamilton had accumulated, Kepler-like.”

Nef, orphaned son of a beloved Chicago professor, ward of another, married a pineapple heiress, and had gone on to write The Conquest of the Material World, in 1964, and, in 1973, a very beguiling The Search for Meaning: autobiography of a non-conformist.

More to the point, though, professional economics had moved on, dramatically. A new Nobel Prize in Economics had been established, first awarded in 1969. Paul Samuelson, a Keynesian (that being the new name that real analysis had acquired), had won the prize its second year, for “raising the general analytical and methodological level in economic science.”

And in 1976, Milton Friedman was recognized “for his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history, and theory; and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy” – that is, for monetary analysis.

I wrote a Forbes cover story, in March 1975, taking note of the unreversed nature of 17th Century price explosion, venturing that it seemed unlikely that deflation, if it occurred, would return price levels to those that prevailed at the beginning of the 20th Century.

Like most journalists untrained in economics, I was partial to the cost-push explanation. Those OPEC price increases weighed heavy in the balance, it seemed to me. Moreover, the mid-’70s saw the beginning to the tax revolt: maybe the unmistakable growth of government since the ‘30s had something to do with it: There were new social programs, nuclear weapons, and rockets to the moon.

Reflecting on the similarities between the 16th and the 20th centuries, I was more intrigued by the emphasis the historian Nef had placed on developments in industry, government, and warfare, than by the changes in the quantity of money that had inarguably taken place, new world treasure then, and central banking now.

Mainly I was struck by the extent to which monetary analysis simply ignored the developments in the real sector that so interested Nef. Instead, monetarists (we were beginning to call them that) pursued their interests in money with apparently no thought for developments “on the ground” and banking. As for Hamilton, I thought of Albert Einstein rather than Johannes Kepler: Einstein had famously asserted, “It is the theory which decides what we can observe.” I had only just begun to read Milton Friedman’s work.

What was needed, I thought, was a theory real events of generality equal to that of the quantity theory, one which that might somehow cover all the ad hoc explanations usually advanced to explain rising prices. Together with a colleague, Lawrence Minard, I persuaded the Forbes editor, James Michaels, to let us prepare a longer piece to say as much. “Growing crops don’t make the sun shine” was a phrase we bandied about freely in those days.

It took some time. Not until other November 1976, a month after Friedman’s recognition was announced, did our lengthy article appear, under the headline “Inflation Is Now Too Important to Leave to the Economists.” A line from a Clark Gable film served as the article’s MacGuffin: “What do you mean they can’t pay more taxes? Tell them to put up the price of beans!” I wince now to see the headline in print, but the story won a Loeb award the next year, and Minard’s career and mine were launched.

There were parts of the argument that first piece made that Minard and I didn’t like. The tax angle was too acute; other angles we had come up with were missing. I persisted; Michaels remained receptive: ten months later Part Two appeared: “The Great Hamburger Paradox: An investigation into how economics went astray” (Wince again)!

This time I was “the author.” The MacGuffin was the contrast between a heavily-staffed an extensively-decorated restaurant with a fancy menu and a hamburger stand. That distinction conveyed well enough the difference between the 16th Century, when an ordinary householder was fortunate to possess a bowl and a spoon, and the 20th. The paradox was the way the labor cost of a hamburger had plummeted over centuries during which its money price continued to rise. This was a proposition about the importance of real factors: I ignored economists’ highly developed framework of supply and demand and conjured a nascent theory of “economic complexity,” employing an intuitively appealing but analytically empty word to connote the difference between degrees of development.

In terms of a restaurant menu, I wrote, the problem might be better understood as the bundling together of various costs, conflation of many costs, rather than the inflation of single price. Wordplay! This was very far from economics, and it wasn’t history, either. It was economic journalism, pure and very simple.

Then came the supply-siders, the “Mundell-Laffer hypothesis” and all that, with their emphasis on tax cuts and their preoccupation with economic growth, which they called an increase of “aggregate supply.” The influence of Steve Forbes, a future presidential candidate, grew at the magazine that his grandfather had founded and his father ran. After I was unable to get a story about James Buchanan, a future Nobel laureate, onto the magazine’s story list, I left for the library and the newspaper business. I had begun to specialize, and for the next forty years, I grew more interested in the economics profession and closer to it with every passing year.

All this came back recently as I browed through A Financial History of Western Europe, by Charles Kindleberger, in connection with another matter. I came across a section on the price revolution. It turns out that prices may have been rising in Europe for decades before the voyages of discovery got underway. The mines of central Europe yielded relatively little gold; silver was draining off to pay for spices imported on camels from the East; Henry the Navigator’s Portuguese sailors were able to sail south to the gold coast of Africa thanks to the invention of fore-and-aft rigging of sails, the stern rudderpost, and the compass; and that Columbus had been sent into the unknown in search of gold. (His diary mentions it 65 times in a voyage of less than a hundred days.) Kindleberger wrote,

Since [Earl] Hamilton’s book came out in 1934, something of a question has arisen whether the discovery of South America produced a price revolution de novo or whether it merely supported one already underway. The argument is a familiar one that we still encounter a number of times – in the debate between the banking and currency schools in nineteenth century England; between those who blame the first Great Depression represented by the fall in prices between 1873 and 1896 on the slowdown of the rate of increase in gold stocks and demonetization of silver, and those who ascribe it to real factors; and again in the explanation of the German inflation after World War I, held by monetarists to be due to simple over-production of money, and by their opponents to a complex set of real factors, including reparations, restocking, speculation, and the like….

The main a priori attack on the price revolution rests on the belief that, apart from the short run when money may be inelastic and halt a boom, money adjusts to trade rather than trade to money as the quantity theory would have it. .. If a clear-cut choice must be made between real factors and the quantity theory of money, this goes to the heart of the issue. But both explanations can be right and leapfrog one another. the bullion famine of the fifteenth century led to a frantic search for money’ the discovery of copious quantities of silver, plus debasement, and perhaps dishoarding and the coinage of plate, supported and extended the price rise which would otherwise had to reverse itself or lead to the development of money substitutes, as happened later. Clearly silver and war leapfrogged, and war is one of the greatest strains of resources and contributors to inflation.

I read the passage twice. Kindleberger’s compression of real and monetary explanations forcefully reminded me of the single most important lesson I had learned from covering professional economics in the fifty years since I wrote those adolescent articles for Forbes.

That clear-cut choice doesn’t have to be made, at least not when considered in the context of the sweet fullness of science and time. It is enough to expect that young economists will continue to do their work. “Inflation,” if that is what it is, is too important not to leave to economists. More on how I learned that lesson next week..

. xxx

Meanwhile, the best article I read last week on Russia’s war in Ukraine is “How to Make Peace with Putin: The West must move quickly to end the war in Ukraine’’, by Thomas Graham and Rajan Menon. First time Foreign Affairs readers may see it for free, I believe.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Chris Powell: Judge Jackson flunks the ‘what is a woman’ test; school daze; United Robots’ mystery building

Graphic by F l a n k e r

MANCHESTER, Conn.

President Biden nominated Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court to fulfill a campaign promise to give the court its first Black woman. But this week Jackson told the Senate Judiciary Committee that she can't define "woman" because "I'm not a biologist."

So how could the president have been so sure as to what constitutes a woman? He's no biologist either.

And how could the Democratic senators supporting Jackson, also no biologists, be so sure even as they are trying to push her through the confirmation process before her judicial and political philosophies are explored too much?

When the hearing on Jackson's nomination began, "woman" was in the dictionary, and had been for a long time.

But Jackson's evasion on the woman question was a strong hint that if she makes it to the court she will assist the extreme political left in promoting transgenderism and erasing any recognition of gender differences, particularly in regard to women in sports.

Of course, for many years all Supreme Court nominees have been evasive about their views on legal and political controversies. But this evasion never has been taken as far as Jackson took it this week.

The Senate should not accept such evasion. It should tell the president that if he wants to nominate a Black woman for the court, he should find one who at least isn't afraid to admit knowing what a woman is.

Hamden (Conn.) High School . The school’s main building was built in 1935 and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The lobby has murals showing scenes from Hamden's history.

— Photo by Streetsim

According to a Rasmussen poll this week, 58 percent of likely U.S. voters think that the public schools are getting worse, with only 13 percent thinking that they are improving.

Of course, the virus epidemic's interruption of schooling has damaged education terribly. But education already had been declining for years and is probably even worse than the 58 percent in the poll believe. A report in the New Haven Independent this week may not have been surprising but still should have been horrifying.

Quoting the city school system's data, the Independent reported that the performance of 45 percent of New Haven students is two grades behind where it should be and the performance of another 44 percent of students is one grade behind. Only 11 percent of New Haven students are performing at grade level.

Since most of the city's children are fatherless and impoverished, New Haven is worse in this respect than Connecticut generally, but statewide student performance should horrify as well. The last time Connecticut's high school seniors were formally tested for subject proficiency was in 2013 by the National Assessment of Educational Progress. While Connecticut's seniors performed best in the country, half still had not mastered high school English and two-thirds still had not mastered high school math.

Even so, contrary to the Rasmussen poll, most people in Connecticut seem satisfied with their public schools. At least there is no movement to improve schools academically or seriously examine student performance.

Maybe opinions about schools are like opinions about Congress, where most people think that Congress is corrupt and taking the country in the wrong direction even as most people like their own members of Congress

After all, there's some comfort in thinking that while schools are declining generally, one's local schools are still great and that, as in Lake Wobegon, all local students are above average. Such thinking relieves parents of any responsibility to take note of public education's transition from academic learning to "social and emotional learning" with a dollop of political indoctrination -- schooling without the inconvenience of proficiency-test scores.

xxx

Connecticut's Hearst newspapers this week published a remarkable news item produced by an outfit called United Robots, whose computer programs process raw data and put it into prose.

This particular item, drawn from property records, said a "spacious and historic house" in Bridgeport with three stories, 3,700 square feet, seven bedrooms, three bathrooms, and a detached garage had been sold for a mere $2,000. A photograph showed the house looks intact and secure.

But the "robots" didn't explain the low price, so incongruous amid Connecticut's housing shortage. Bridgeport is a troubled city but residential property there is not worthless. There must be a reason for the giveaway price of that house but the "robots" apparently lack the curiosity of a live reporter.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Rachael Conway: Meeting looks for ‘equitable pandemic recovery’ at N.E. community colleges

Main entrance to Bunker Hill Community College, in Boston’s Charlestown section.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

Rather than return to the pre-COVID-19 state of affairs, policy change is needed to strengthen each leg of the “three-legged stool” of community college success: students’ financial stability, learning inside the classroom, and wraparound support services on campuses, Bunker Hill Community College President Pam Eddinger told the New England Board of Higher Education’s Legislative Advisory Committee (LAC) last week.

The LAC, comprising state lawmakers who are delegates to NEBHE and a few additional sitting legislators from each state, has been convening twice a year since 2013, with each LAC meeting featuring national and regional experts on a pressing higher-education topic.

On March 14, NEBHE hosted its first in-person pandemic-era LAC meeting since 2019 at Lasell University in a hybrid format, with some attendees and panelists joining via Zoom. The first half of the LAC meeting featured a panel discussion on “Doing the Most with the Least: How State Policymakers can Support Wellbeing, Belonging and Success at Community Colleges for an Equitable Pandemic Recovery.”

Panelists included Eddinger, along with: Sara Goldrick-Rab, award-winning author, professor and founder of the Wisconsin HOPE Center for College, Community, and Justice; Linda García, executive director of the Center for Community College Student Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin; Alfred Williams, president of River Valley Community College, in New Hampshire; Audrey Ellis, director of institutional effectiveness at Northern Essex Community College, in Massachusetts; and Eudania Aquino, a Northern Essex Community College Student Ambassador. Joining the meeting in-person, Ellis and Aquino spoke powerfully about Northern Essex’s new Student Ambassador program, a peer-to-peer mentoring program created during the pandemic to foster belonging on the campus as most students had to shift to online learning.

The second part of the LAC meetings offer a colorful snapshot of legislative session updates in the six states, giving lawmakers an opportunity to learn and share models with one another.

The panel discussion and legislative updates yielded rich discussions about challenges and opportunities in postsecondary education facing the region after two years of COVID. Here are five takeaways from the spring 2022 LAC meeting:

1. New England states should look beyond traditional avenues of financial aid to support community college students. Community colleges serve the majority of the nation’s low-income, working and parenting students. These students have much to gain from earning a high-quality college credential. While many New England states administer some form of need-based financial aid, even the lowest-income students still face significant gaps in college affordability, particularly if they are enrolled part-time (as are roughly two-thirds of community college students). Goldrick-Rab advocated for federal emergency aid to become permanent, and urged New England states to follow the lead of states like Wisconsin, Minnesota and Washington, which have instituted state-based emergency funding to ensure that students do not stop-out of college due to being short, say, $300 (a seemingly manageable obstacle but enough to derail an education). She also discussed installing specialists on college campuses dedicated to connecting students to existing public benefits, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

2. Community colleges were struggling to serve students before COVID, and the pandemic added stress to an already-strained system. Eddinger of Bunker Hill in Massachusetts did not mince words: “pre-COVID is no better than post-COVID.” The change, in her words, came from seeing what happened when “we put community college systems through the stress-test” of COVID. Everything—resources, staff, materials and time—“was short, and families were backed up against the wall.” Williams noted that his River Valley Community College serves primarily rural and female students. He underscored his students’ ongoing need for support in the areas of internet connectivity, food and child-care services.

3. Federal CARES funding supported programming at community colleges temporarily, but states must invest in permanently supporting these institutions and their students. Eddinger described federal dollars as “patching a hole.” Ellis outlined how temporary funding from the federal CARES Act allowed Northern Essex Community College to create its Student Ambassadors program, which pays students to serve as peer mentors for students identified as at risk of not persisting. Aquino elaborated on her experience as a Student Ambassador, stating that part of the program’s success comes from its recognition that students benefit from persistent communication and various modes of outreach. García of Texas added that her Center for Community College Student Engagement found that students in danger of not persisting—such as men of color, one of the sector’s most vulnerable groups—felt most connected to their institutions when professors and staff knew their names, helped them establish a long-term plan for their time at the community college, and identified potential barriers to their success. Eddinger remarked on a temporary program at Bunker Hill that provided a small stipend to students in addition to covering tuition and fees, noting, “We realized that it’s not about being able to pay for school. It’s about being able to pay for life.” All of these proven interventions require investing more dollars into community colleges.

4. Faced with declining enrollment, several New England states are looking at college mergers. Connecticut state Sen. Derek Slap (D.-West Hartford), who chairs the state’s Higher Education & Employment Advancement Committee, noted that the state’s General Assembly is moving forward with its plan to consolidate the state’s 12 community colleges into one college with multiple campuses, making it the fifth largest community college in the country. He remarked that the bill has been controversial; some stakeholders are worried that the move will erase the individuality of campuses. Additionally, New Hampshire state Sen. Jay Kahn (D.-Keene) provided an update that lawmakers in New Hampshire are moving ahead with the merger of Granite State College with the University of New Hampshire. Massachusetts state Rep. Jeffrey Roy (D.-Franklin) remarked that the state passed a law in 2019 offering an off-ramp to closing institutions. In the wake of sharp enrollment declines during Covid, mergers represent one method that New England states are embracing to keep public colleges afloat.

5. Every state in the region is working on various efforts to improve college access and affordability. Lawmakers at the March 14 LAC meeting told the group that the Connecticut and Massachusetts legislatures recently pursued bills that address food insecurity on college campuses. Connecticut aims to expand funding for first-time students of its free community college program with additional resources this legislative session. New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Connecticut have introduced legislation supporting student mental health on college campuses. Massachusetts Rep. Patricia Haddad (D.-Somerset), the NEBHE chair, discussed the legislature’s push to expand college access to students with developmental disabilities and autism. The Massachusetts and Connecticut legislative representatives also remarked on their states’ student-debt reimbursement initiatives, which would primarily focus on loan forgiveness for human services and health-care workers.

Look for similar themes around the region in NEBHE’s Legislative Session Summary report outlining current post-secondary and workforce development bills in the six New England states.

Rachael Conway is a NEBHE policy and research consultant who manages the LAC.

Always busy

“Grandma’s Hands” (encaustic with embedded photo on raised panel), by Oty Merrill.

Ms. Merrill says:

“Though I am surrounded by magnificent landscapes and brilliant natural light on the coast of Maine where I live and work, I tend to turn inward when making art, drawing on memories, travels and emotions. Through color, texture and often embedding photos and other materials into the surfaces of my work, I lean towards semi-abstract and interpretive imagery in my compositions. I admire the works of artists such as Harold Garde (of Maine), Milton Avery, Marsden Hartley and Mary Cassatt. You might see their influences in my work. I strive to be honest, original and hopefully a little unique, both in my artwork and my life.’’

‘There be dragons’

The Babcock House in Charlestown, built in the late 17th or early 18th Century.

—- Photo by JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ, M.D.

The town’s Quonochontaug section had an iron-mining operation financed by Thomas A. Edison in the 1880s. There were iron particles in the form of black sand on the beach there that could be separated out with magnets and melted to produce iron. But the venture collapsed after cheaper iron was later discovered.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

For such an amusingly tiny place, Rhode Island has intense localisms. Consider Kevin Gallup’s remarks. He’s a former police officer and now director of the Emergency Management Agency in Charlestown, in the exurban south of the state.

Mr. Gallup ominously warned, in comments about PVD Food Truck Events coming to Charlestown, that “things morph’’ and town residents “might not appreciate” having people from Providence come to town for events.

“If we’re going to have people showing up from Providence and hanging out that we don’t know…along with our children…some people aren’t going to appreciate that and I can tell you that for a fact. So you’re going to need that police detail. Sorry the world needs to be this way, but these things need to be thought out.”

There’s a long tradition of seeing cities as a source of menace, including in a “city state’’ such as Rhode Island. Do Charlestown people feel safer with visitors from smaller city New London, Conn., 34 miles from Charlestown, than with people from Providence, 48 miles away?

Remember those old maps that had the Latin phrase “hic sunt dracones” (“there be dragons”) for dangerous and/or unexplored regions? One wonders how familiar Charlestown people are with the capital of their state, and how many would say they’re all too familiar with it. People can be very provincial around here, and I’ll bet plenty of people from South County have never been to Providence.

Quonochontaug Pond.

‘From sea’s slime’

The town on Nantucket Island, when it was still called Sherburne, in 1775.

“Here in Nantucket, and cast up the time

When the Lord God formed man from the sea's slime

And breathed into his face the breath of life,

And blue-lung'd combers lumbered to the kill.’’

— From “The Quaker Graveyard at Nantucket,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977)

Well-papered Edwardian Boston

Boston’s “Newspaper Row’’ in 1910, when the city had seven daily papers.

The University of Maine’s ‘factory of the future’

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) message

“The University of Maine has been approved for $35 million in funding to build a new digital research laboratory. These funds were made possible under the omnibus spending bill that President Biden recently signed into law last week. This facility is an initiative of UMaine’s Advanced Structures and Composites Center and is a “factory of the future,” according to UMaine. It is being created to advance “large-scale, bio-based {material from living or once-living sources} additive manufacturing,” using technologies such as artificial intelligence and 3D printers.

“The cost of building this facility is expected to total $75 million. According to the university, the center’s new capabilities could lead to technology development in the affordable-housing industry, clean energy, transportation industry and more.’’

Llewellyn King: We must face the fact that world crises in food, inflation and energy require tough decisions and new thinking

Messengers going to Job, each with bad news.

— 1860 woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a rough road ahead for the world and our political class isn’t leveling with us.

As Steve Odland, president and CEO of The Conference Board, one of the nation’s premier business-research organizations, said in a television interview, serious inflation will continue at least until 2024, and longer if things continue to deteriorate with supply-chain crises and the war in Ukraine.

Particularly, Odland, who also serves as a director of General Mills Inc., fears a global food crisis with famine in Africa and many other vulnerable places if Ukrainian farmers don’t start seeding spring crops to start this year’s harvest. Already, Ukraine – once known as one of the world’s breadbaskets -- has cut off exports to make sure that there is enough food for their own people, as war rages.

Odland sees U.S. inflation continuing at 7 to 8 percent for several years at best. But his primary worry is global food supplies, as countries face a crisis of new and frightening proportions.

His second worry is stagflation. If the rate of productivity falls below 3 percent, “then we will have stagflation,” Odland told me during a recording of White House Chronicle, on PBS, the weekly news and public affairs program I produce and host.

Odland faults the Federal Reserve for being timid in raising interest rates to counter inflation.

I fault the political class for not leveling with us – both parties. As we are in a state of perpetual election fervor, we are also in a state of perpetual happy talk. “Get the rascals out, and all will be well when my band of happy angels will fix things.” That is what the political class says, and it is a lie.

We are in for a long and difficult period which began with the pandemic that disrupted supply chains and set off inflation, and now the war in Ukraine has compounded that. Supply chains won’t magically return to where they were before COVID-19 struck, and more likely they will have further constrictions because of the war. New supply chains need to be forged and that will take time.

For example, nickel, which is used in the batteries that are reshaping the worlds of electricity and transportation and for stainless steel, will have to come from places other than Russia. At present, Russia supplies 20 percent of the world’s voracious appetite for high-purity nickel. Opening new mines and expanding old ones will take time.

The world’s largest challenge is going to be food: starvation in many poor countries and high prices at the supermarkets in the rich ones, including the United States. There are technological and alternative supply fixes for everything else, but they will take time. Food shortages will hit early and will continue while the world’s farms adjust. There will be suffering and death from famine.

The curtailing of Russian exports will affect the United States in multiple ways, some of which might eventually turn out to be beneficial as the creative muscle is flexed.

In the utility industry, someone who is thinking big and boldly is Duane Highley, president and CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association in Denver.

Highley told Digital 360, the weekly webinar that emanates from Texas State University in San Marcos, the challenging problem of electricity storage could be solved not with lithium-ion batteries, but with iron-air batteries.

In its simplest form, an iron-air battery harnesses the process of rusting to store electricity. The process of rusting is used to produce power when it is exposed to oxygen captured on site. To charge the battery, an electric current reverses the process and returns the rust to iron.

Clearly, as Highley said, this won’t work for electric vehicles because of the weight of iron. But in utility operations, these batteries could offer the possibility of very long drawdown times --not just four hours, as with current lithium-ion batteries. And there is plenty of iron stateside.

Another Highley concept is that instead of dealing with all the complexities of transporting hydrogen, it should be stored as ammonia, which is more easily handled.

This isn’t magical thinking, but the kind of thinking which will lead us back to normal -- someday.

Politicians should stop the happy talk and tell us what we are facing.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C

It all depends on what you mean by ‘new’

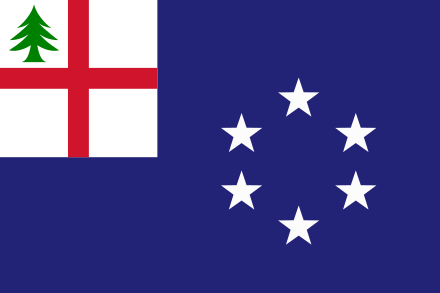

The New England Flag.

“New England is the illegitimate child of Old England….It is England and Scotland again in miniature and in childhood.’’

Calvin Colton, in Manual for Emigrants to America (1832)

xxx

“Of course what the man from Mars will find out first about New England is that it is neither new nor very much like England.’’

— John Gunther, in Inside U.S.A. (1947)

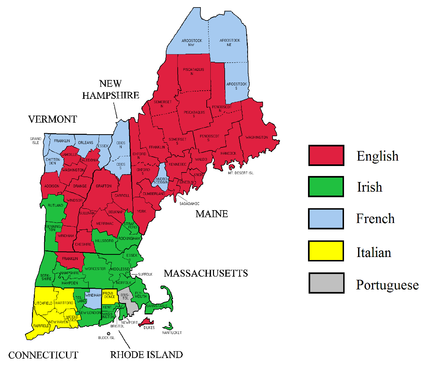

New England by background ethnicity

Better go by land

“River Currents” (oil on panel), by Cambridge, Mass.-based artist Wendy Prellwitz at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.