Or a mushroom cloud

“The Tree” (etching), by Marguerite Thompson Zorach (American, 1887-1968), at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass. For a while a Californian, she later lived in New York City and in her family’s summer house in Georgetown, Maine.

Five Islands, Georgetown, Maine, from a circa. 1906 postcard published by G. W. Morris.

The museum says:

"Marguerite Thompson Zorach is best known for her early modernist paintings and late embroidery creations. One of the first women to be admitted to Stanford University, in 1908, she was invited to study in Paris by her aunt, which changed the course of her career. There she met Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Gertrude Stein (1874-1946). She attended the avant-garde school La Palette, where she met her future husband, artist William Zorach. During this time, she created etchings like this delicate rendering entitled “The Tree,’’ thought to be an olive tree with olive pickers resting nearby.’’

To read more please click here.

Mountainous conception

Part of Avon Mountain, in Connecticut. It’s known for its microclimate.

“The night you were conceived

your father drove up Avon Mountain {near Hartford}

and into the roadside rest

that looked over the little city,

its handful of scattered sparks.’’

— From “Breaking Silence — For My Son,’’ by Patricia Fargnoli (1937-2021), an American poet and psychotherapist. She grew up in Connecticut and later moved to Walpole, N.H. (best known as the home of TV history-documentary maker Ken Burn’s Florentine Films) and on the Connecticut River. She was the New Hampshire Poet Laureate from December 2006 to March 2009.

Walpole’s public library in 1906. The famous and highly literary and reformist Alcott family, connected to the Concord, Mass.-based Transcendentalists, lived there for a time in the 1850s, as have other writers and painters, drawn by the region’s great natural beauty. The abundant lilacs in the town inspired Louisa May Alcott (who wrote Little Women) to write the 1878 book Under the Lilacs.

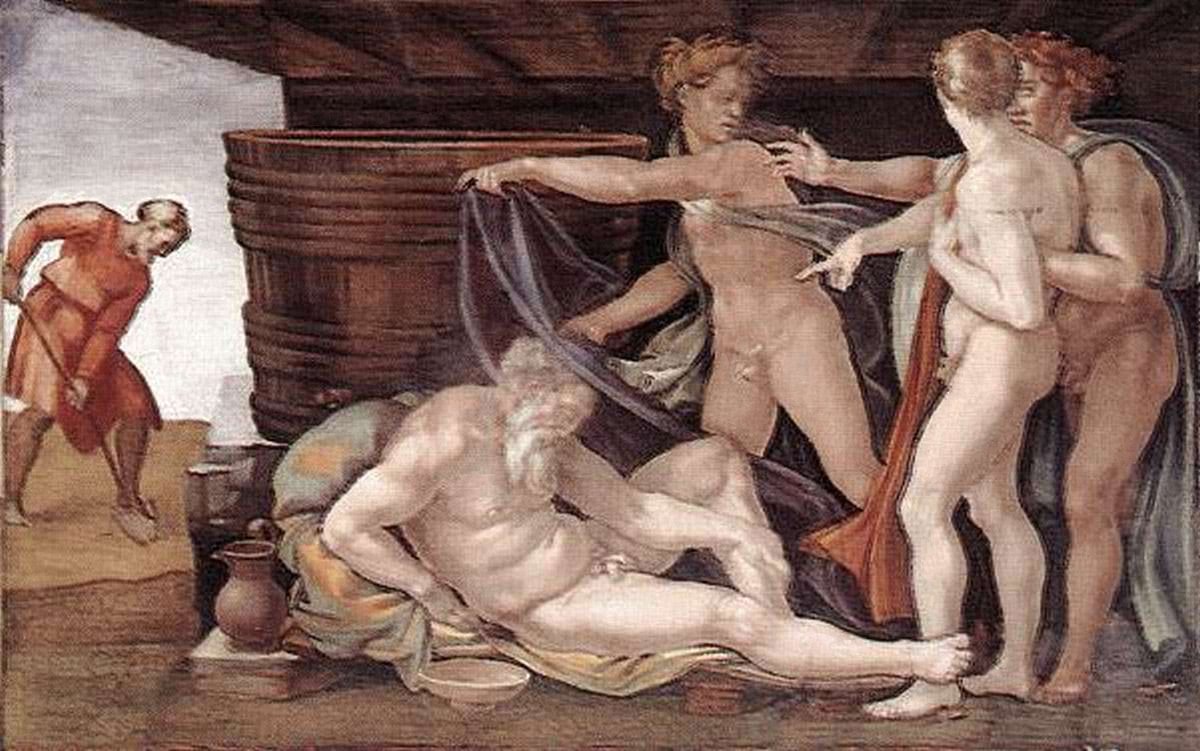

David Warsh: Putin the drunken grandfather goes on rampage and changes everything

“Drunken Noah,’’ by Michelangelo

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Russia has experienced a difficult thirty years searching for its place among nations. The U.S. hasn’t made it easier, inducting the former East European satellites of the USSR into NATO, bullying Russia’s former client-states along the country’s southern rim and around the Mediterranean. China, which maintained Communist Party control while opening its economy to the world, has rocketed past its rival.

Boris Yeltsin anointed Vladimir Putin as his successor because the former KGB officer-turned-politician was “thoughtful, democratic, and innovative – yet steadfast in the military manner.” And for 22 years, Vladimir Putin has done a pretty good job of rebuilding the social fabric, economic infrastructure and military forces of his country, while navigating the narrow corridor between authoritarian rule and anarchy – until last week.

{Editor’s note: In 2005, Putin said: “We should acknowledge that the collapse of the Soviet Union was a major geopolitical disaster of the {20th} Century.’’

But as New York Times Moscow bureau chief Anton Troianovski wrote Thursday:

His attack on Ukraine negated that image, and revealed him as an altogether different leader: one dragging the nuclear superpower he helms into a war with no foreseeable conclusion, one that by all appearances will end Russia’s attempts over its three post-Soviet decades to find a place in a peaceful world order.

The war on its neighbor Ukraine is a tragedy, for all involved, most all for Russia. Fred Weir, of The Christian Science Monitor, a special correspondent and long-time Moscow resident, supplied the clearest view. The assault “amounts to a war of regime change,” patterned on America’s war against Iraq. Weir wrote:

Very few Russian security analysts were picking up their phones Thursday. It seems many have been blindsided by the speed with which Mr. Putin has acted after spelling out his grievances in a lengthy speech officially recognizing two east Ukrainian rebel republics barely three days earlier.

But those who did claimed that the operation – which none will call an “invasion” – was going well, that Russia has established dominance in the air, that much of Ukraine’s military and command-and-control infrastructure had already been greatly reduced, the Ukrainian army in the Donbass region surrounded, and many strategic points seized by Russian special forces.

That doesn’t square with reports on the ground from the first three days of the war. Ukrainian soldiers and citizens have put up determined resistance. The U.S. invasion of Iraq isn’t parallel for a variety of reasons. Besides, that war was a disaster. The arguments about NATO encroachment that Putin had used before to good effect, in 2007 and 2014, didn’t work this time; instead the four-term Russian president sounded demented.

No matter who tries to stand in our way or all the more so create threats for our country and our people, they must know that Russia will respond immediately, and the consequences will be such as you have never seen in your entire history.

Nor did domestic propaganda and suppression of dissent make his case stronger. Evoked instead are memories of East Germany in 1953, Hungary in 1956, Berlin in 1961, and Czechoslovakia in 1968.

It all makes it seem more likely that something has happened to Putin’s judgment. Speculation is rampant about what might have led to an elevated appetite for risk. Alexei Navalny, the Russia dissident who has been sentenced to two years in prison (with more trials yet to come), remains free enough to have tweeted that Putin’s conduct resembles that of a drunken grandfather who spoils family celebrations. (See the bottom of a very good story by Robyn Dixon and Paul Sonne of The Washington Post.)

The problem of U.S. swagger is more widely recognized today, at home and aboard, even though its sources have yet to be carefully examined. Now the question of succession, in Russia, as in the US, has become the more interesting story.

xxx

Giving up on someone for whom you’ve had a fair amount of sympathy for a long time years is dispiriting. Putin gave a speech on Thursday, as expected; some of the grievances he enumerated were real enough, at least in some degree; in no way do they justify the measures taken. There is absolutely nothing to be said, at least for Putin’s decision to wage war against Ukraine.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Sokeconomicprincipals.com

And ‘at the mercy of’

“Four Seasons,’’ by Alphonse Mucha (1897)

“Nowhere in the United States of America does the wheel of the seasons turn more brilliantly than in New England. Winter’s blankets of white, the long-awaited buds of spring accompanied by the run of sap, summer’s bouquets, and the magnificent palette of autumn: all are feasts for the senses, and lead to the characteristic New England feeling of existing in tandem with, and often at the mercy of, the great forces of nature.’’

Tom Shachtman (born 1942, Connecticut-based writer and filmmaker), in The Most Beautiful Villages of New England (1997)

In Lexington, Mass., after April 16, 2021 snowstorm.

With affordable gondolas?

The Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston’s increasingly flood-prone Seaport District

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report

BOSTON

“The Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) has seen significant interest from developers for a residential project with an affordable focus that the authority wants to build on land off D Street in Boston’s Seaport district. Massport has reported that nine teams have expressed a serious interest in the project.

“Massport estimates that its 27,000-square-foot site, adjacent to its South Boston parking garage, could accommodate a tower with as many as 18 stories and 200 apartments. The bidding teams are: Beacon Communities and RISE Together, The Community Builders and Menkiti Group, Cruz Development Corp., L&M Development Partners, The Michaels Organization and Boston Partnership for Community Reinvestment, Preservation of Affordable Housing and DREAM Development, Standard Communities, the Cronin Group, and the Caribbean Integration Community Development, Trinity Financial and the South Boston Neighborhood Development Corp., and Winn Companies and Catalyst Venture Development. Massport is expected to issue a formal request for proposals in the late spring or early summer.

“The New England Council commends Massport for working towards building affordable housing in the Seaport.’’

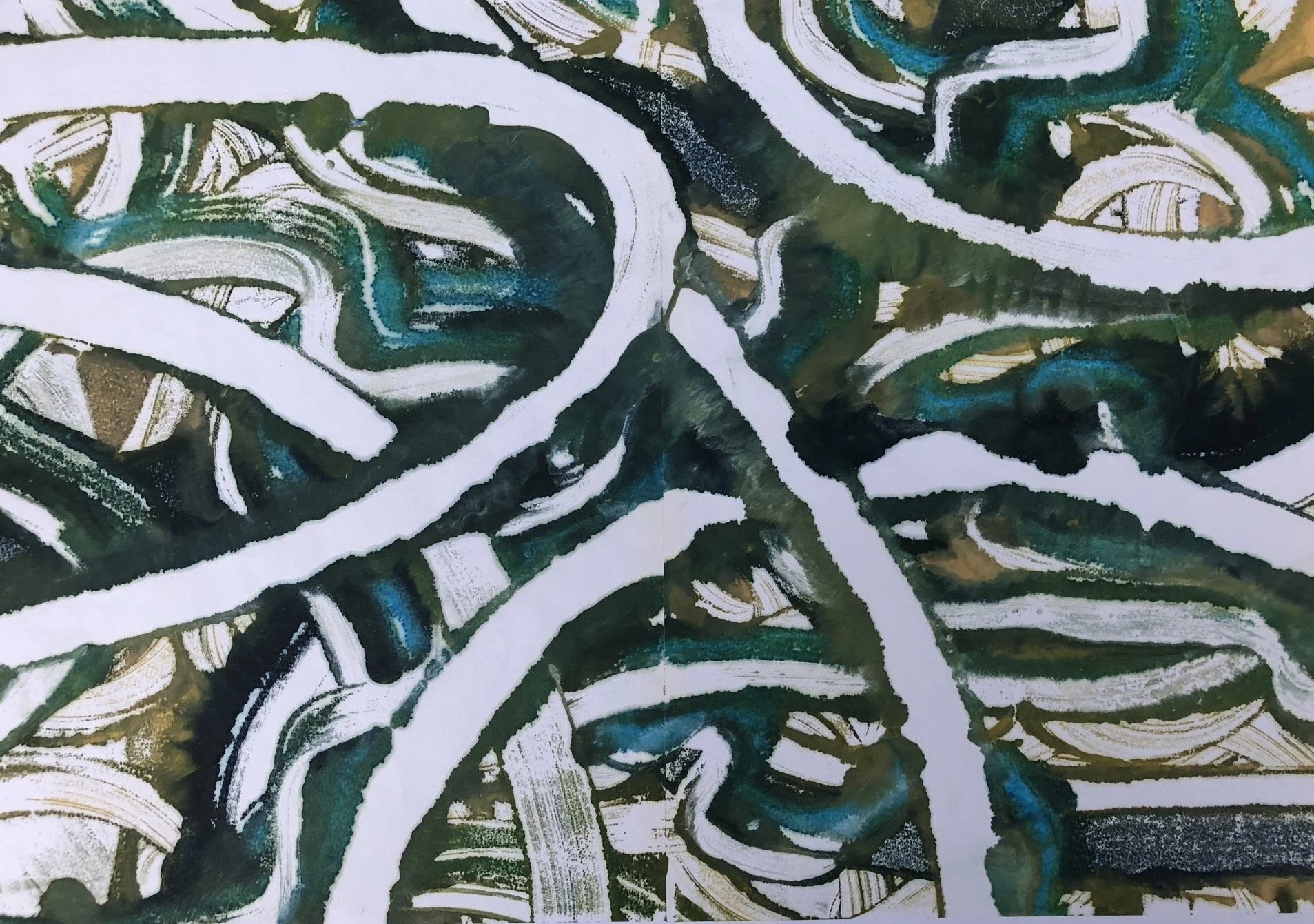

‘Symbols of the Dreamtime’

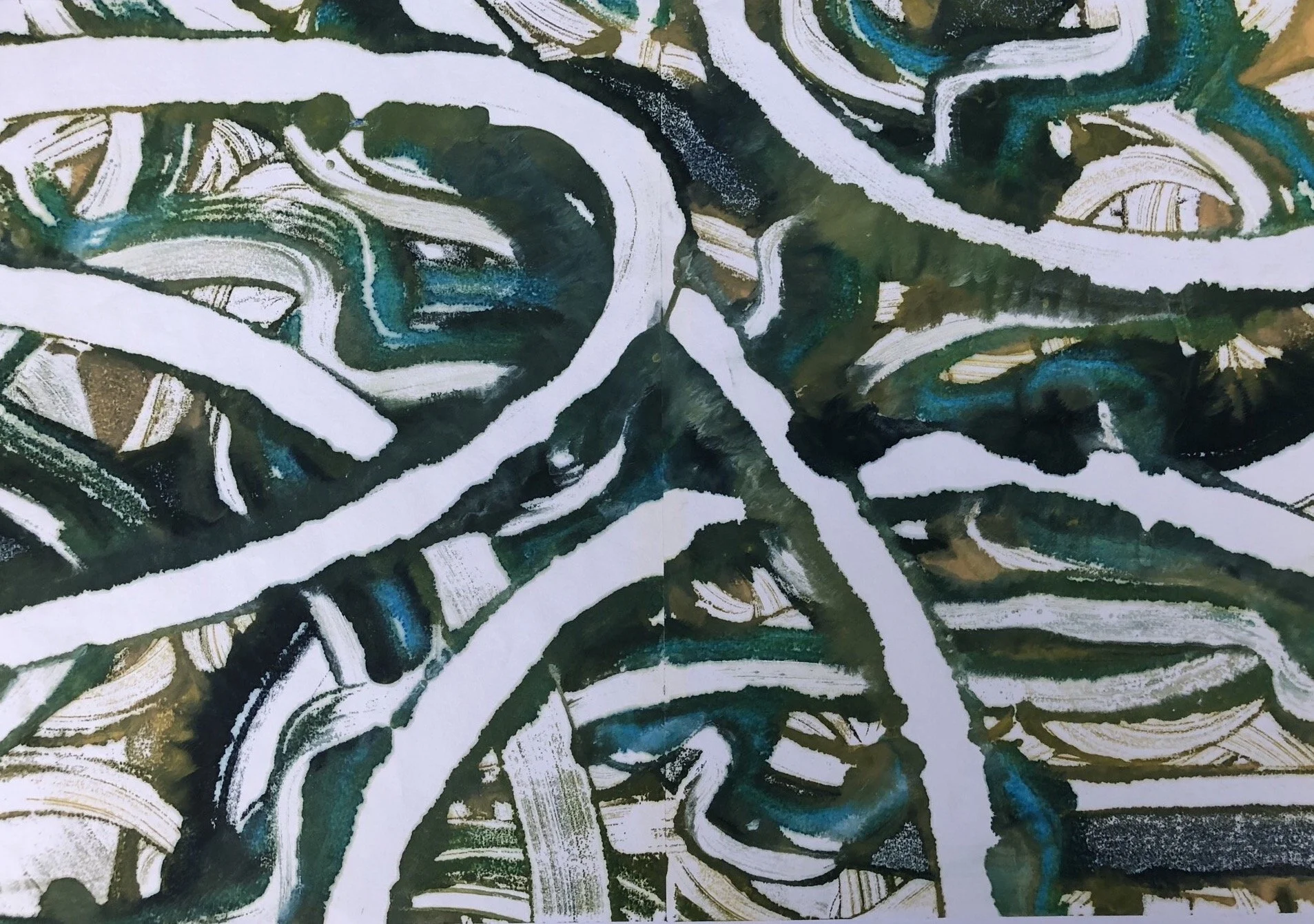

“Dreamtime-Rendevous” (encaustic monotype), by Acton, Maine-based artist Ken Eason.

Mr. Eason writes:

“Several years ago, vacationing in Australia with family, I was introduced to Aboriginal Art and was fascinated by the technique, symbolism and variety. Aboriginal Art is centered on telling the ancient stories of the Aboriginal peoples using symbolism and metaphor. The imagery is described as symbols of the ‘Dreamtime,’ which is the Aboriginal understanding of nature and the world.

“This series explores my own personal ‘Dreamtime’ where I can be physically at home but mentally, spiritually and emotionally away. I use line as symbol of path, thought, or journey. These lines tend to overlap in many layers, each curve signifying a decision point, change in direction or choice.’’

— Photo circa 1920

Edited from a Wikipedia entry:

“{Acton, which is west of Portland} was first settled in 1776, by Benjamin Kimens, Clement Steele and John York, all from York, Maine. In 1779, Joseph Parsons built a gristmill on the Salmon Falls River, near Wakefield, N.H. Other mills followed at Acton's various water power sites, including sawmills, gristmills, a hemp mill, a carding mill, a felt mill, a tannery and a shoe factory. In 1877, silver was discovered near Goding Creek. Prospectors dug mines during the 1880s, after which the enterprise declined.’’

That was then

The front entrance to a mall in Milford, Conn.

— Photo by JJBers

"When I was growing up, in the 1950s, my grandparents had a farm outside Hartford, {on} one of the four corners of a crossroads. The farm was surrounded by orchards, and there was a skating pond for the winter and blueberry bushes for July and August picking. By the time I was a teenager, the three other corners were being filled in, and there were supermarkets and gas stations standing on old farmland. By the time I got out of college, my grandparents’ farm had become a regional shopping mall.’’

-- Robert Yaro, as quoted in Tony Hiss's The Experience of Place (1990).

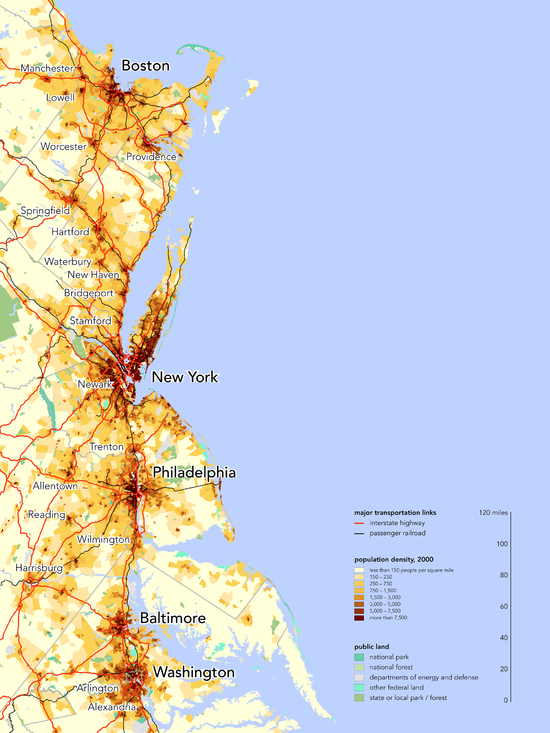

Population density in the Northeast megalopolis.

Spraying the slopes; curling isn’t actually silly

Mount Snow, in Dover, in southern Vermont. The ski area has long had one of America’s biggest “snow’’-making operations.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I wonder how long ski areas will be allowed to take so much water to use to make artificial snow to spray on trails even in areas with water shortages. And as the fake snow melts, it increases erosion on slopes. Further, at some ski areas, chemical additives are used to boost “snow’’ production. (China claims it hasn’t used additives in its fake-snow making at the Beijing Olympics. Beijing, by the way, has suffered water shortages for years.)

As the climate warms, this will be more and more of an issue.

Speaking of The Olympics, what other sport combines so weirdly decorum and seeming silliness as curling, which originated in Scotland? Players slide heavy polished granite stones on ice toward a target area segmented into four concentric circles and use brooms to reduce friction in a stone’s path. It’s rather hard to watch without chuckling.

I had an aunt on Cape Cod who was a curler. After I joked about it, she responded with dignity: “No, no, it’s a real sport. Lots of skill.’’

“Curling—a Scottish Game, at {New York’s} Central Park” (1862), by John George Brown

Plastic Providence

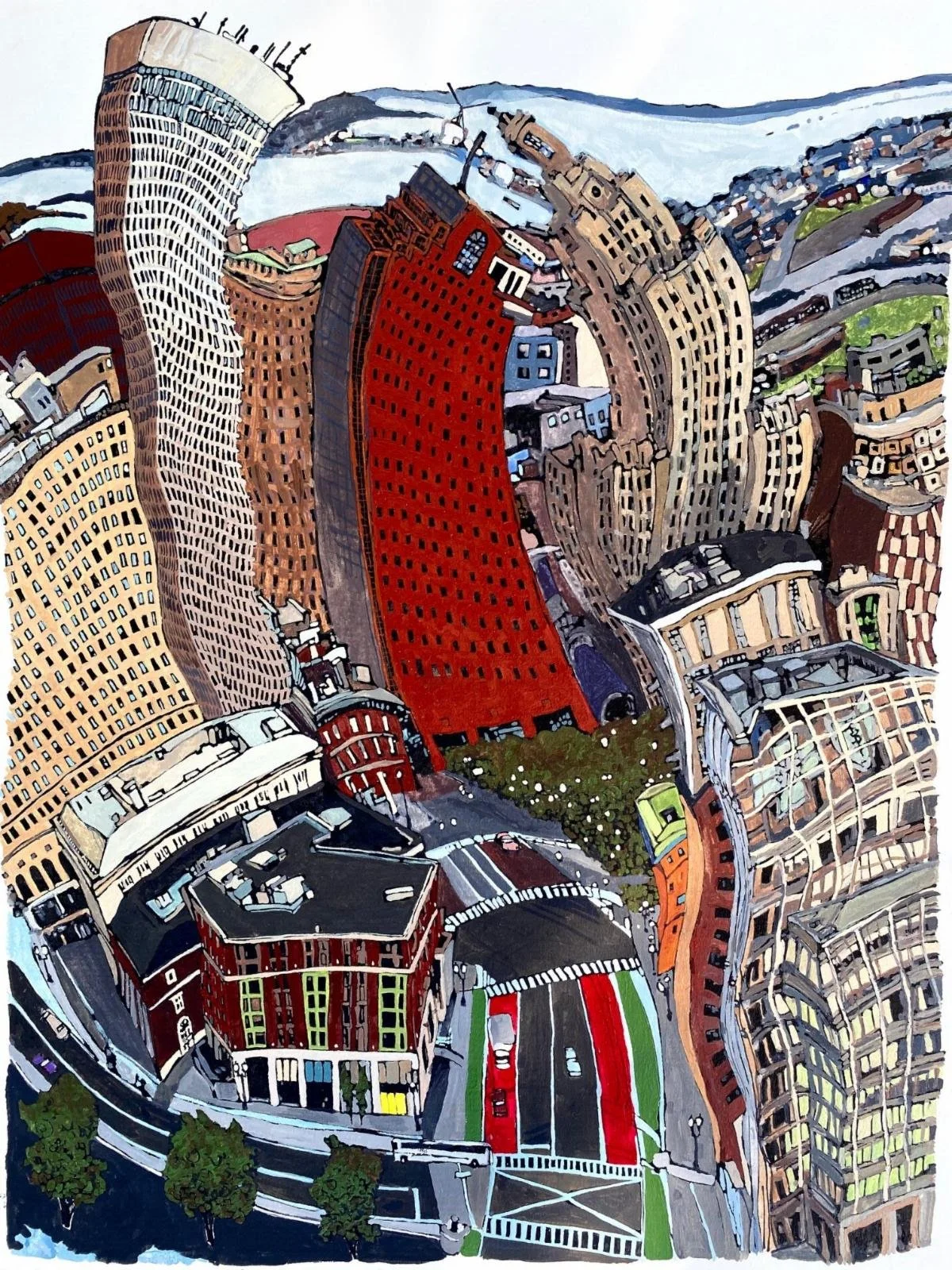

This work by Rhode Island artist Jim Bush can be seen at the Providence Art Club March 6-25.

Here’s his description of his background:

“Jim Bush grew up in Cambridge, Mass., and graduated from Kenyon College with a double major in Studio Art and Political Science. He is an award-winning artist, member of the Providence Art Club and a former member of the Sakonnet Artists Cooperative, in Tiverton, R.I. His editorial cartoons appeared in The Providence Journal from 1994-2012. Nationally his cartoons have appeared in the Washington Post National Weekly Edition, The Dallas Morning News and he has drawn for the Tribune Media Services College Press Syndicate.

“In 2007, Jim purchased a building in the historic district of downtown Warren, R.I. and spent a year converting it into an art studio and gallery. Jim focuses now on his fine art painting, primarily acrylic and watercolor. He enjoys painting animals, seascapes, landscapes, farm scenes, architecture -- life around him. His style continues to reflect his cartooning foundation, often displaying his subjects in a light-hearted and off-beat way.’’

The end of his quarrel and road

Robert Frost’s grave, in Bennington, Vt.

— Photo by Nheyob

One of the most famous — and misunderstood — poems in the English Language, first published in 1915

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

— “The Road Not Taken,’’ by Robert Frost

In The Paris Review critic, poet and essayist David Orr described some of the misunderstanding this way:

“The poem’s speaker tells us he ‘shall be telling,’ at some point in the future, of how he took the road less traveled…yet he has already admitted that the two paths ‘equally lay / In leaves’ and ‘the passing there / Had worn them really about the same.’ So the road he will later call less traveled is actually the road equally traveled. The two roads are interchangeable.’’

Like ‘moving through a landscape’

“Aerial View” (cold wax, oil stick, graphite on bristol board), by Deborah Pressman, a Chestnut Hill, Mass.-based artist.

“Landscapes and multiple images produced by double- and triple-image photography are recurrent themes in my work. I am interested in expanding and compressing the depth of field: seeing the micro and the macro world simultaneously. Weather, changing seasons, the profusion of textures and shapes within the natural world are constant sources of wonders and inspiration. My goal is the create a visual experience as though moving through a landscape.’’

“In June 2017 I retired after 33 years of practicing medicine. Throughout my medical practice I continued to make art – I took master classes in silversmithing for 8 years with renowned silversmith Michael Banner. More recently, I have taken prolonged workshops with Lisa Pressman (no relation) in encaustic painting, and printmaking workshops with Joyce Silverstone at Zia Mays and Dan Weldon at North Country Studio Workshops, in Bennington, Vt. I currently participate in a monthly critique group led by Patricia Miranda. I am fully committed to art making, working daily in my studio.’’

Chestnut Hill (Mass.) Reservoir in January. View of Boston College's Alumni Stadium across the water.

— Photo by Marball135

Start those nippy Maine mornings well-carbed

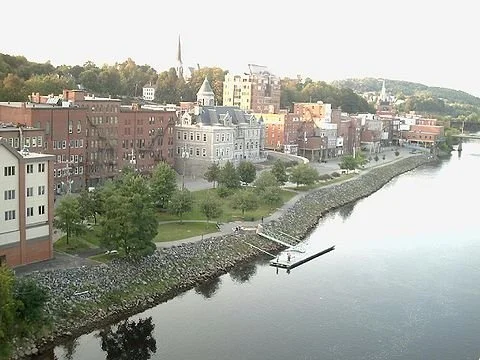

The Kennebec River flowing along downtown Augusta, Maine’s capital.

“I’m from Maine. I eat apple pie for breakfast.’’

— Rachel Nichols, actress and model, was born in Augusta in 1980.

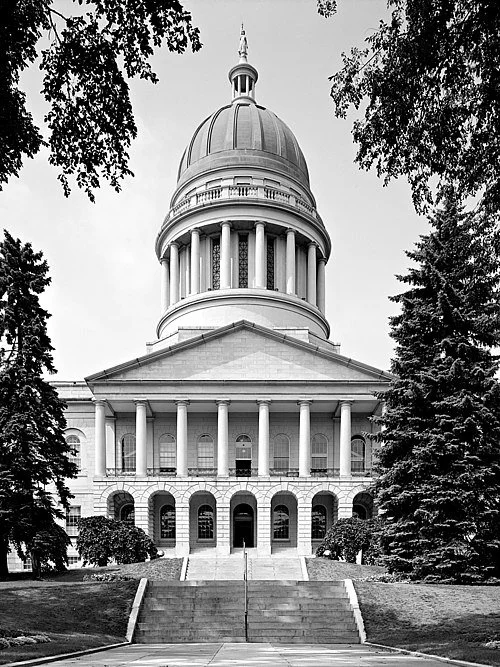

Maine State House, designed by Charles Bulfinch, built 1829–1832. Bulfinch more famously designed the Massachusetts State House. Maine was part of the Bay State until 1820.

William Morgan: Paying homage to a young Maine hero

— Photo by William Morgan

Pine Grove Cemetery, in Appleton, Maine, is not easy to find. This rural community beyond the Camden Hills has a post office, a library and a fast-running stream where a mill once stood; the town office is open only three days a week. An elementary school serves the town, but middle and high- school students must travel by bus to Camden.

My wife and I drove down a road with an Abenaki name and across the Saint George River, up a steep hill to a ridge, in search of a barely marked turnoff. We bumped along a rutted dirt track to one of those ancient New England burying grounds with slate steles carved with primitive angels.

The grave we searched for was not under the elegiac oaks and dark conifers, but in the new part. This half of the cemetery has few trees, and the gravestones tend to be more elaborate, colored and polished. Many are adorned with plastic flowers, teddy bears and other tributes of contemporary mourning. The vertical marble slab we were visiting had not been tended in a while. Veterans of Vietnam and the Persian Gulf rest nearby.

On Feb. 26, 2006, Joshua Humble, a specialist in the famed winter warriors of the 10th Mountain Division, was killed near Baghdad by a roadside bomb – the 2,385th U.S. soldier to die in Iraq. Humble had just turned 21. A regimental honor guard stood by his coffin at a funeral home in Belfast, then followed the hearse to Appleton for burial.

Thousands of kids died in the Iraq War. What was so special about one from an agricultural community in Maine? Was he like so many soldiers: high school, limited local prospects and maybe a desire to get away from small-town life?

A newspaper obituary shows a face of aching innocence. His middle initial was intriguing: Did the “U.” stand for Ulysses, Uriah or maybe Uncas? His stone revealed that the U. was for Ut, an Asian anomaly in an all-white Appleton.

Josh Humble is remembered primarily through an ongoing memorial on Legacy.com. There have been 47 comments since Humble’s death, most from buddies in arms who speak of his heroism. Five years ago, Julie Lee, from the Maine town of Washington, recalled Josh as “a respectful kid with a fun sense of humor.” She added, “Your sacrifice for our country will not be forgotten.”

Yet recent war deaths such as Humble’s have been forgotten – only an average of three notes a year on an obituary, and memorial Web site is not much of a remembrance. These are the young men and women of a volunteer military who carried the load while the rest of us did not face roadside bombs in the desert.

I was drafted in 1966 but was determined not to be sent to Vietnam. After passing my Army physical, I implored an orthopedic surgeon – my college roommate’s father – to write a letter outlining how a skiing injury would make me unfit for basic training. Contemporaries who did not have such connections went to Southeast Asia, and of course some died there. Maybe unforgetting one Maine soldier would offset the shadow of my not having donned a uniform.

Since reading of Josh Humble’s death 15 years ago, we had talked of paying our respects at his final resting place. It was a bucolic, almost secret, graveyard on a perfect autumn day. I was glad we went. But as I placed a stone on Josh’s marker, I did not feel peace or closure. Instead, I was overcome by a rage that took me back to the protests of my youth. For me, Joshua Humble symbolizes the tragedy of nonsensical wars that robbed hundreds of places like Appleton of their young people and their future.

William Morgan is an architectural writer and a resident of Providence who has taught at Princeton University, the University of Louisville and Brown University, among other institutions. He went to camp in Litchfield, Maine, in the 1950s.

Camden, Maine, near Appleton, viewed from the summit of Mt. Battie, one of the Camden Hills.

— Photo by Dudesleeper

Valley grandeur

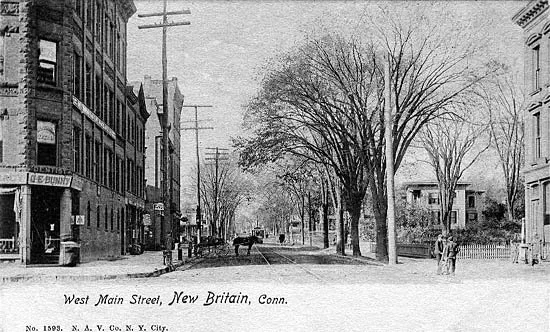

“Autumn Woods, Oneida County, State of New York” (oil on linen), by Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), in the show “The Poetry of Nature: Hudson River School Landscapes from the New York Historical Society,’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art through May 22.

Look at the elm trees!

Eversource touts New London as offshore-wind staging site

Rendering of State Pier project in New London

From reporting by The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Eversource Energy has made progress in its siting process for wind-power turbines in the Atlantic. According to Eversource CEO Joseph R. Nolan Jr., State Pier in New London, Conn., is a ‘superior location’ to assemble these turbines, with the company preparing to spend billions of dollars in the coming years developing wind power in the region. Expansion of State Pier to make the location suitable to wind-turbine assembly is in the works.

Eversource spokeswoman Caroline Pretyman says that State Pier’s proximity to offshore leases presents a ‘strategic opportunity’ for the industry to site facilities for wind-turbine parts assembly. This project is associated with Eversource’s development of Revolution Wind, a 704-megawatt offshore wind farm that will supply 400 megawatts of power to Rhode Island and 304 megawatts to Connecticut. Nolan said supply-chain problems over the past few months have driven up costs higher than expected but he remains confident in Eversource’s upcoming projects and optimistic about their environmental impacts.

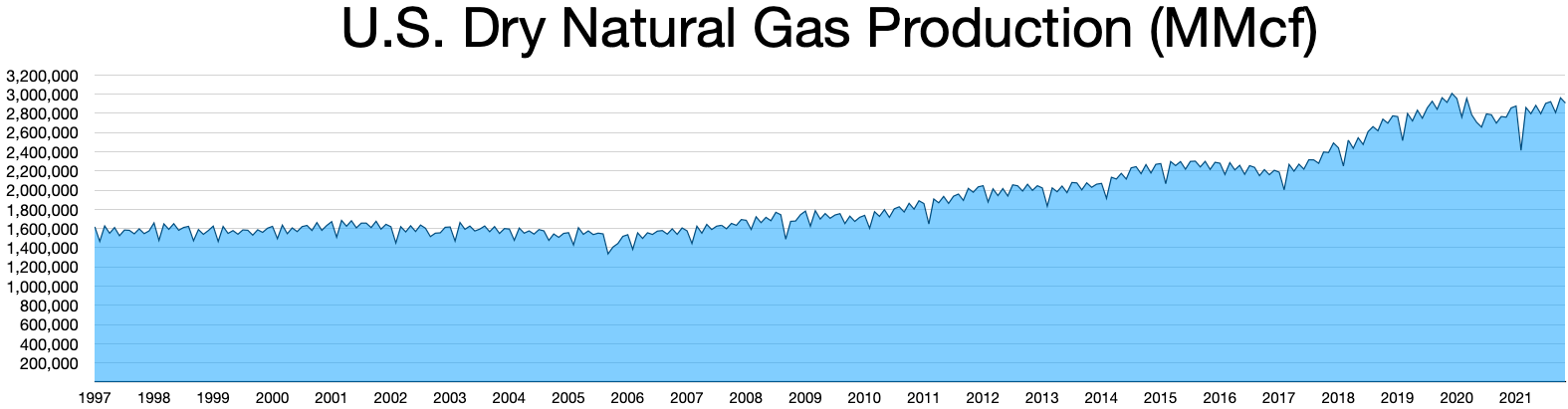

Llewellyn King: Russian assault on Ukraine emphasizes need for more U.S. natural-gas production

Liquified natural gas tanker.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Natural gas has been getting short shrift in the U.S. energy debate. It deserves better. Much better.

It has been battered by environmentalists who oppose exploration and the pipelines to get it to market. They are attempting to evict natural gas and force utilities into reliance on intermittent renewables.

But events in Europe may cause a rethink about natural gas, both as a transition fuel in the United States and a foreign-policy tool.

Even before Russia's invasion of Ukraine, natural gas was in short supply in Europe after a summer of wind drought caused European utilities to scramble for natural gas – prices went up 400 percent. Russia added to the crisis by reducing volumes flowing through the Ukrainian system that serves much of Europe.

Fear of Russian weaponization of natural gas has been an ever-present reality. Now Europe trembles, especially Germany which has just closed its last three nuclear plants and has relied on renewables and natural gas from Russia.

In the United States, the danger is that natural gas may be pushed aside prematurely in favor of renewables, leaving the electric grid destabilized and vulnerable to severe weather. The grid is less stable today than it was 20 years ago, according to experts I speak to regularly. Environmental mandates are taking a toll, and natural gas is being pushed out before there are stable renewables and utility-scale storage.

A new assessment of natural gas is needed. Its value to the United States to counter Russia now and in the future isn’t in doubt. The United States is the world’s largest natural-gas producer, and liquefied natural gas is needed as a diplomatic tool.

Domestically, though, it needs a defined place in the electricity evolution. It is an option too valuable to be elbowed out by well-meaning but not well-informed arguments.

In electricity production, natural gas is the least polluting of the three fossil fuels. It emits half the carbon dioxide of coal and heavy oil used to make electricity. Also, it doesn’t have the other pollutants which make coal so devastating to the environment. Progress is being made countering methane leaks, a serious problem.

When burned in a combined-cycle plant, favored by utilities for more than just peaking, natural gas reaches an efficiency of around 64 percent. That is a remarkably high rate of fuel to electricity. Coal-fired plants have an efficiency of about 40 percent.

Back in the 1970s, a combination of price controls and regulation served to dry up the amount of natural gas coming to market. The newly formed Department of Energy added to the sense of an end by declaring that gas was “a depleted resource.” The conventional wisdom was that it was too precious for most uses and especially for making electricity.

In 1978, Congress passed the Power Plant and Industrial Fuel Use Act. It was a prohibiting measure and went after what Congress thought were wasteful uses of natural gas such as ornamental flames and pilot lights in gas stoves. And it prohibited the burning of natural gas to make electricity.

Known simply as the “Fuel Use Act,” it was draconian. There was even a debate about whether the Eternal Flame at Arlington National Cemetery would have to be extinguished.

In 1985, deregulation began to increase the natural gas supply and two years later, the Fuel Use Act was repealed.

But the big break, the great game-changer, was fracking -- first used in the late 1980s. It was developed by George Mitchell and his Mitchell Energy company with help from the DOE. Together with horizontal drilling, it would change everything quickly.

Natural gas became cheap and plentiful and the utilities, using turbines developed from aircraft jet engines, began to switch off coal and to question the cost of building nuclear plants. A new dawn had broken.

Now that happy day is in the past and utilities must make the case for gas turbine capacity to back up their alternative energy operations and as an efficient form of energy storage. Also, if hydrogen is to be the fuel of the future, it will need to use the natural-gas infrastructure.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He is also a well-known international energy-sector expert and consultant. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Chris Powell: Lessons of Enfield’s pizza/sex crisis

Is this your preferred topping?

Innocent-looking Thompsonville Village in Enfield, a large town in Hartford County where the biggest employer is the U.S. headquarters of Lego, the Danish toy company.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Republican state legislators around the country are proposing to require public schools to post all curriculum materials on the Internet as an accountability measure, and the other day they got powerful if inadvertent support from Enfield, Conn.’s school system.

Enfield's school administration acknowledged that an eighth-grade class had been given an assignment in which students were instructed to choose pizza toppings as a sort of code to signify the sex acts they preferred. The objective seems to have been to teach the 14-year-olds that sex, like pizza, should be consensual and negotiated.

The Enfield incident, first publicized by a national parents group, was picked up by news outlets far and wide and put the town on the world map for stupidity.

The school administration apologized and attributed the assignment to a mistake of absentmindedness. That is, a different assignment involving pizza choices but without the sexual allusions, also aiming to teach consent and negotiation, was meant to be used. But this account evaded the big questions.

How did the pizza/sex assignment get into the school system in the first place? Exactly where did it come from? Why is the school system receiving such material? Who authorized it?

And why, in a state where most students graduate from high school without mastering basic math and English, is a school system using a Family Health and Human Sexuality class to teach students, even without sexual allusions, what they already know from their own experience with pizza and life generally -- that when ordering for more than oneself, the preferences of others must be considered?

It's all beyond moronic, even if it is the work of people holding degrees in education and drawing at tax expense annual salaries of $100,000 or more.

Responding to the proposals to require all curriculum materials to be posted on the internet, teachers and school administrators around the country insist that they are not hiding anything and that they make curriculum materials available to anyone who asks. But this is evasive.

For having a misplaced faith in schools, few people do ask, and few people might think they need to ask to see any curriculum materials likening pizza toppings to sex acts or imputing to white students guilt for the mistreatment of racial minorities throughout history.

Yet such materials are indeed in use in American schools, precisely because they are not routinely publicized and easily accessible.

Enfield's Board of Education may appoint a committee to look into the pizza-sex assignment and how a recurrence might be prevented. This too is moronic, for the school superintendent already should be able to answer the big questions. It is distressing and revealing that they were not answered at the board meeting when the incident was discussed at length.

The problem here isn't the sexual prudery of parents or other observers. The Internet distributes pornography so widely that Enfield's eighth-graders already may know more about sex than their parents do. No, the problem is the unaccountability of public schools.

Yes, posting on the Internet all curriculum material will facilitate many questions and complaints, and some will be mistaken, arise from prudery, or have bad intent. But that's democracy, which inevitably is less convenient for government than totalitarianism, a lesson schools should teach -- perhaps most of all to their own staff.

But will any legislators in Connecticut propose a curriculum-posting law and thus risk the ire of the teacher and school administrator unions? (Yes, in Connecticut most school administrators, supposedly managers, are unionized too and so not really managers.)

Any such legislation shouldn't stop with curriculums. It also should require the posting of school salaries and teacher evaluations, thereby repealing Connecticut's law exempting teacher performance evaluations from disclosure, the law's only exemption for evaluations of government employees.

Of course the teacher and administrator unions surely would dissuade the governor and General Assembly from enacting that much accountability in public education. But a discussion of accountability legislation at least might establish that the big problem with public education in Connecticut is that it's not really public at all

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Malaise of elderly grows as pandemic grinds on

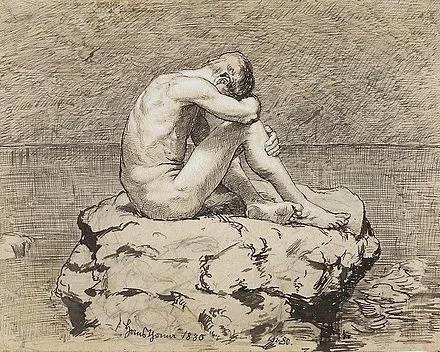

“Loneliness,’’ by Hans Thoma, in the National Museum in Warsaw.

“Folks are becoming more anxious and angry and stressed and agitated because this has gone on for so long.’’

— Katherine Cook, chief operating officer of Monadnock Family Services in Keene, N.H., which operates a community mental-health center that serves older adults.

Late one night in January, Jonathan Coffino, 78, turned to his wife as they sat in bed. “I don’t know how much longer I can do this,” he said, glumly.

Navigating Aging focuses on medical issues and advice associated with aging and end-of-life care, helping America’s 45 million seniors and their families navigate the health care system

Coffino was referring to the caution that’s come to define his life during the COVID-19 pandemic. After two years of mostly staying at home and avoiding people, his patience is frayed and his distress is growing.

“There’s a terrible fear that I’ll never get back my normal life,” Coffino told me, describing feelings he tries to keep at bay. “And there’s an awful sense of purposelessness.”

Despite recent signals that COVID’s grip on the country may be easing, many older adults are struggling with persistent malaise, heightened by the spread of the highly contagious omicron variant. Even those who adapted well initially are saying their fortitude is waning or wearing thin.

Like younger people, they’re beset by uncertainty about what the future may bring. But added to that is an especially painful feeling that opportunities that will never come again are being squandered, time is running out, and death is drawing ever nearer.

“I’ve never seen so many people who say they’re hopeless and have nothing to look forward to,” said Henry Kimmel, a clinical psychologist in Sherman Oaks, California, who focuses on older adults.

To be sure, older adults have cause for concern. Throughout the pandemic, they’ve been at much higher risk of becoming seriously ill and dying than other age groups. Even seniors who are fully vaccinated and boosted remain vulnerable: More than two-thirds of vaccinated people hospitalized from June through September with breakthrough infections were 65 or older.

The constant stress of wondering “Am I going to be OK?” and “What’s the future going to look like?” has been hard for Kathleen Tate, 74, a retired nurse in Mount Vernon, Wash. She has late-onset post-polio syndrome and severe osteoarthritis.

“I guess I had the expectation that once we were vaccinated the world would open up again,” said Tate, who lives alone. Although that happened for a while last summer, she largely stopped going out as first the delta and then the omicron variants swept through her area. Now, she said she feels “a quiet desperation.”

This isn’t something that Tate talks about with friends, though she’s hungry for human connection. “I see everybody dealing with extraordinary stresses in their lives, and I don’t want to add to that by complaining or asking to be comforted,” she said.

Tate described a feeling of “flatness” and “being worn out” that saps her motivation. “It’s almost too much effort to reach out to people and try to pull myself out of that place,” she said, admitting she’s watching too much TV and drinking too much alcohol. “It’s just like I want to mellow out and go numb, instead of bucking up and trying to pull myself together.”

Beth Spencer, 73, a recently retired social worker who lives in Ann Arbor, Mich., with her 90-year-old husband, is grappling with similar feelings during this typically challenging Midwestern winter. “The weather here is gray, the sky is gray, and my psyche is gray,” she told me. “I typically am an upbeat person, but I’m struggling to stay motivated.”

“I can’t sort out whether what I’m going through is due to retirement or caregiver stress or covid,” Spencer said, explaining that her husband was recently diagnosed with congestive heart failure. “I find myself asking ‘What’s the meaning of my life right now?’ and I don’t have an answer.”

Bonnie Olsen, a clinical psychologist at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, works extensively with older adults. “At the beginning of the pandemic, many older adults hunkered down and used a lifetime of coping skills to get through this,” she said. “Now, as people face this current surge, it’s as if their well of emotional reserves is being depleted.”

Most at risk are older adults who are isolated and frail, who were vulnerable to depression and anxiety even before the pandemic, or who have suffered serious losses and acute grief. Watch for signs that they are withdrawing from social contact or shutting down emotionally, Olsen said. “When people start to avoid being in touch, then I become more worried,” she said.

Fred Axelrod, 66, of Los Angeles, who’s disabled by ankylosing spondylitis, a serious form of arthritis, lost three close friends during the pandemic: Two died of cancer and one of complications related to diabetes. “You can’t go out and replace friends like that at my age,” he told me.

Now, the only person Axelrod talks to on a regular basis is Kimmel, his therapist. “I don’t do anything. There’s nothing to do, nowhere to go,” he complained. “There’s a lot of times I feel I’m just letting the clock run out. You start thinking, ‘How much more time do I have left?’”

“Older adults are thinking about mortality more than ever and asking, ‘How will we ever get out of this nightmare,’” Kimmel said. “I tell them we all have to stay in the present moment and do our best to keep ourselves occupied and connect with other people.”

Loss has also been a defining feature of the pandemic for Bud Carraway, 79, of Midvale, Utah, whose wife, Virginia, died a year ago. She was a stroke survivor who had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atrial fibrillation, an abnormal heartbeat. The couple, who met in the Marines, had been married 55 years.

“I became depressed. Anxiety kept me awake at night. I couldn’t turn my mind off,” Carraway told me. Those feelings and a sense of being trapped throughout the pandemic “brought me pretty far down,” he said.

Help came from an eight-week grief support program offered online through the University of Utah. One of the assignments was to come up with a list of strategies for cultivating well-being, which Carraway keeps on his front door. Among the items listed: “Walk the mall. Eat with friends. Do some volunteer work. Join a bowling league. Go to a movie. Check out senior centers.”

“I’d circle them as I accomplished each one of them. I knew I had to get up and get out and live again,” Carraway said. “This program, it just made a world of difference.”

Kathie Supiano, an associate professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing who oversees the COVID grief groups, said older adults’ ability to bounce back from setbacks shouldn’t be discounted. “This isn’t their first rodeo. Many people remember polio and the AIDS epidemic. They’ve been through a lot and know how to put things in perspective.”

Alissa Ballot, 66, realized recently she can trust herself to find a way forward. After becoming extremely isolated early in the pandemic, Ballot moved last November from Chicago to New York City. There, she found a community of new friends online at Central Synagogue in Manhattan and her loneliness evaporated as she began attending events in person.

With Omicron’s rise in December, Ballot briefly became fearful that she’d end up alone again. But, this time, something clicked as she pondered some of her rabbi’s spiritual teachings.

“I felt paused on a precipice looking into the unknown and suddenly I thought, ‘So, we don’t know what’s going to happen next, stop worrying.’ And I relaxed. Now I’m like, this is a blip, and I’ll get through it.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

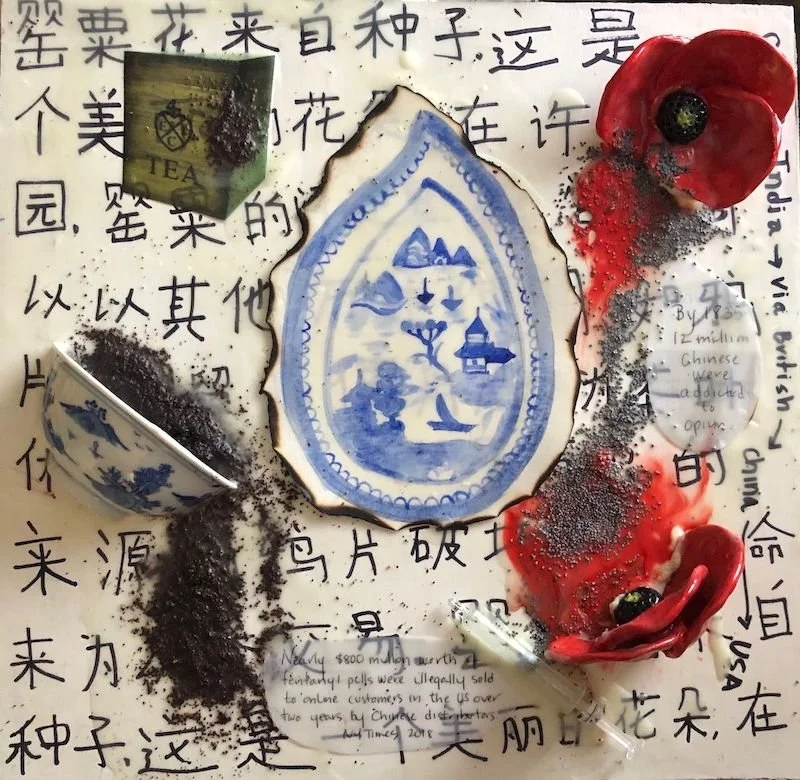

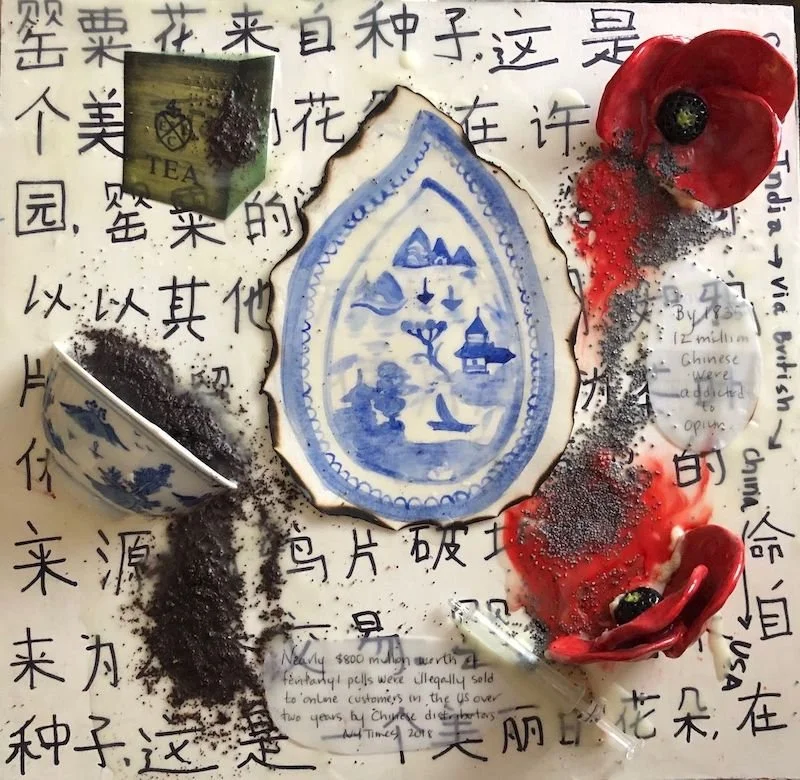

Beauty from New England’s drugged-up China Trade

“China Trade: Opium through the Ages” (encaustic, ceramic made and found objects, tea leaves, poppy seeds on panel), by Cambridge,Mass.-based artist Katrina Abbott.

New England’s “China Trade,’’ in the late 18th Century and the first half of the 19th, created great wealth for some in the region, mostly in and around its ports. Some of the trade involved selling opium to the Chinese. Much of that wealth was invested in what became very lucrative industries, such as textile, shoe and machinery manufacturing and railroads.

In her Web site, Ms. Abbott describes herself thusly:

“Katrina Abbott came to art later in life after her twins were born. Previous to this, she spent 25 years in education, including outdoor education, ocean education at sea and urban public school reform. With a BA in Environmental Biology and a Masters in Botany (studying seaweed!), she reflects her interest in and concern for the natural world in her art. She represents the nature in print, paint, wax ( encaustic) and mosaic. She is a member of the Cambridge Art Association and New England Wax and lives in Cambridge with her husband, their 20 year old boy/girl twins and small brown rabbit named Jarvis.’’

Derby House, in Salem, Mass. Elias Hasket Derby was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary War merchants in Salem. He was owner of the Grand Turk, said to be the first New England vessel to be used to trade directly with China. There were many mansions built by merchants in the China Trade, some of which was a drug trade.

—Photo by Daderot