Good show for a stony region

“Water and Rocks” (print on aluminum), by Robin MacDonald-Foley, in her show “Seeing Stone,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, March 5-28.

She tells the gallery:

"Seeing Stone is a journey of exploration represented as a body of work inspired by forms and shapes found in nature. Uniting stone and stone’s relationships within the natural environment is my focus. Pairing sculpture and photography, these stone carvings and images play upon spatial relationships, intending to draw the viewer in. This work is a personal narrative, depicting the power, calm and permanence of stone.

“In my recent work, visualizing places becomes part of my sculpture. A carving of a vessel takes me on an inward journey navigating oceans and eroded facades etched in lichen stories noting the passage of time. Studying stone as an object, thoughts are captured as photographic impressions of rocks against a blue sky. Bound together by fate, they stand on their own, each central to my theme.

“My work is carved by hand in a steady rhythm of tool to stone, a challenging technique that enables me to bond with a piece over long periods of time. When its form emerges, history begins anew. Working with multiple pieces, I imagine how they connect in color and texture, allowing the placement of objects to redefine permanent qualities. Sometimes a polished finish brings the coloration of an alabaster carving to life, or a self-portrait becomes part of my setting. Sitting by the ocean, or sheltering in cave-like stone structures, my feet intuitively absorb Earth's undulating destinations. I sit quietly sharing time and space with the stone."

She lives in the town of Stoughton, south of Boston.

‘

Downtown Stoughton.

Downtown Stoughton in 1912. Even many small towns had streetcars then.

Why not leave them all on the beach?

“One cannot collect all the beautiful shells on the beach,’’ in Gift From the Sea (1955)

— Anne Morrow Lindbergh (1906-2001), best-selling essayist/author, some of whose writings presaged the Green Movement, and aviator. She was wife of aviator, inventor, military officer, Nazi sympathizer (like her for a time) and womanizing (and with simultaneous-multiple families) Charles Lindbergh. She spent her final years living near her daughter Reeve, an author herself, in the northern Vermont village of Passumpsic, part of the town of Barnet. Before then she and her husband lived off and on in Darien, Conn. (“Aryans from Darien’’), in a rich section on Long Island Sound.

The Barnet, Vt., post office

1914 postcard. But the Lindberghs were not contented.

Carey Goldberg: Boston physician named to run CDC uses data to save lives

Dr. Rochelle Walensky

BOSTON

In early December, Dr. Katy Stephenson was watching TV with her family and scrolling through Twitter when she saw a tweet that made her shout.

“I said ‘Oh, my God!'” she recalled. “Super loud. My kids jumped up. My husband looked over. He said, ‘What’s wrong, what’s wrong, is everything OK?’ I was like, ‘No, no, it’s the opposite. It’s amazing. This is amazing!'”

Dr. Rochelle Walensky had just been tapped to lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Stephenson is an infectious-diseases specialist and vaccine scientist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, in Boston. So the news had special meaning for her and the many jubilant colleagues tweeting their joy. They’d been helping one another through the brutal pandemic year, she said, while feeling they had little to no help from the federal government.

“It was so baffling,” she said. “It wasn’t even just that we didn’t know what the government was doing. It was that sometimes it felt like sabotage. Like the federal government was actively trying to mess things up.”

But through it all, as the long months became a year, Walensky had been out front, Stephenson said, sticking to the science and telling the truth.

When Walensky stepped up to lead the CDC, she promised to keep telling the truth — even when it’s bad news. She told a JAMA Network podcast last month that she’ll welcome straight talk from the scientists at the CDC as well.

“They have been diminished,” she said. “I think they’ve been muzzled — that science hasn’t been heard. This top-tier agency, world-renowned, hasn’t really been appreciated over the last four years and really markedly over the last year, so I have to fix that.

Walensky, 51, has long been a doctor on a mission — first, to fight AIDS around the world, and now, to shore up the CDC and get the United States through the pandemic. Beyond unmuzzling her agency’s staff, she vows to tackle many other challenges, pushing particularly hard on vaccine distribution and rebuilding the public health system.

Walensky’s family has a tradition of service, including a grandfather who served in World War II and rose to be a brigadier general. And she likens the call she got from the Biden administration to a hospital alarm that goes off when a patient is in cardiac arrest.

“I got called during a code,” she told JAMA. “And when you get called during a code, your job is to be there to help.”

At Massachusetts General Hospital, where Walensky was the chief of infectious diseases, some of her many admirers now have T-shirts that read “Answer the Code” with her initials, RPW, beneath.

The shirts are part of an outpouring of affection in Boston biomedical circles and far beyond that greeted Walensky’s appointment — including a flood of floral bouquets that her husband and three sons helped accept after word of her new job got out.

“At one point, one of my sons said, ‘You know, Dad, we should just open a florist shop at this point,” said Dr. Loren Walensky, the CDC director’s husband.

He studies and treats children’s blood cancers at Boston Children’s Hospital and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. And now he could be called the “first gentleman” of the CDC.

He calls Rochelle his “Wonder Woman” and still remembers when he first saw her 30 years ago, in the cafeteria of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where they were both students.

“She stood out,” he said. “And one of the reasons why she stood out is because she stands tall. Rochelle is 6 feet tall.”

She also had extraordinary energy and discipline, even then, he remembered: “Most of us would roll out of bed and stumble into the lecture hall as our first activity of the day and, for Rochelle, she was already up and running and bright-eyed and bushy-tailed for hours before any of us ever saw the light of day.”

After medical school, Rochelle Walensky trained in a hospital medical unit so tough it was compared to the Marines. It was the mid-’90s, and the AIDS epidemic was raging. She saw many people die. And then, a few years later, she saw the advent of HIV treatments that could save patients — if those patients could get access to testing and care.

Loren Walensky recalls coming home one day to find her sitting at the kitchen table working on extremely complex math. She was starting to broaden her focus from patient care to bigger-picture questions about the increased equity in health care that more funding and optimal treatment choices could bring.

“And it was like a switch went off,” he said, “and she just had this natural gift for this style of testing — whether if you did X, would Y happen, and if you did X with a little more money, then how would that affect Y? And all of these if-thens.”

She started doing more research, including studies of ways to get more patients tested and treated for AIDS, even in the poorest countries. One of her most prominent papers calculated that HIV drugs had given American patients at least 3 million more years of life.

She worked with Dr. Ken Freedberg, a leading expert on how money is best spent in medicine.

“You can’t do everything,” Freedberg said, “and even if you could, you can’t do everything at once. So what Rochelle is particularly good at is understanding data about treatments and public health and costs, and putting those three sets of data together to understand, ‘Well, what do we do? And what do we do now?'”

So, if Walensky had a Wonder Woman superpower, it was using data to inform decisions and save lives. That analytic skill has come in handy over the past year, as she has helped lead the pandemic response for her Boston hospital and for the state of Massachusetts.

She has weighed in often — and publicly — about coronavirus policy and medicine, speaking to journalists with a seemingly natural candor that has contrasted with the stiffer style of some federal officials. In April, when a huge surge of covid cases hit, she acknowledged the pain.

“We are experiencing incredibly sad days,” she said in a spring interview. “But we sort of face every day with the hope and the vision that what we will be faced with, we can tackle.”

And in November, she offered a sobering reality check from the front lines about current covid medical treatments: “When I think about the armamentarium of true drugs that we have that benefit people with this disease, it’s pretty sparse,” she said.

Walensky published research on key pandemic topics, such as college testing and antibody treatments. And she weighed in often publicly — on Twitter, in newspapers and on radio and TV. Asked on CNN whether the President Joe Biden’s plan to get 100 million Americans vaccinated in 100 days could restore a sense of normalcy, she responded with characteristic bluntness — a quality that could cause trouble in these polarized times.

“I told you I’d tell you the truth,” she said. “I don’t think we’re going to feel it then. I think we’re still going to have, after we vaccinate 100 million Americans, we’re going to have 200 million more that we’re going to need to vaccinate.”

Walensky is facing a historic challenge and leading an agency for which she’s never worked.

Already, she’s fielded blowback for the new CDC guidance on when and how schools should reopen, and she’s openly worried about new, more transmissible variants spreading nationwide.

Still, Boston colleagues said they have no doubt that she’ll succeed in making the transition from leading an infectious diseases division of 300 staffers to a public health agency of about 13,000.

“I would lie down in traffic for her,” said Elizabeth Barks, the infectious diseases division’s administrative director at Mass General. “And I think our entire division would lie down in traffic for her.”

Leading and rebuilding the CDC in the midst of a pandemic will be difficult. But Barks and others who know Walensky well said she’s clear-eyed and ready to dig in to meet the challenge; she’ll try a new approach if first attempts fall short.

Walensky brought a plaque from her desk in Boston to CDC headquarters in Atlanta. It reads: “Hard things are hard.”

Cory Goldberg is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

This story is part of a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR and KHN.

'Forms a furry sphere'

Palomides

Purrless my cat can stroll away

Rejecting human cheer.

To the same corner wends its way

And forms a furry sphere.

How cordial is the mystery

Of feline solitude.

Until I beckon spaciously

And he returns for food.

— Felicia Nimue Ackerman.

This poem first appeared in the Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin.

Kayla Soren: Small towns need public transit, too

A bus of the Berkshire Regional Transit Authority, which serves Berkshire County, Mass., much of which is rural.

— Photo by Cogiati

Via OtherWords.org

With the pandemic taking a devastating toll on local budgets, the U.S. public transit system is battling to survive. For much of the country, this funding crisis jeopardizes an already withering lifeline.

For many Americans, public transit is the only option to get to work, school, the grocery store, or doctor’s appointments. But nearly half of us have no access to public transit. And those that do are now confronting limited routes, slashed service times, and limited disability accommodations.

This isn’t just a worry for people who live in cities — over a million households in rural America don’t have a vehicle. In rural communities like Wolfe County, Ky., Bullock County, Ala., and Allendale County, S.C., fully 20 percent of households don’t have a car.

Recently, dozens of transit riders and workers joined together for a two-day national community hearing to testify about their needs for public transit.

“My bus pass is the key to my independence,” testified Kathi Zoern, a rider from Wausau, Wis., with a vision impairment. But limited routes prevent her from performing basic tasks. “I can’t get to the Department of Motor Vehicles to get my voter ID,” she said, “because it’s outside the city limits.”

Unfortunately, situations like this are typical. Over 80 percent of young adults with disabilities are prevented from doing daily activities due to a lack of transportation. And there aren’t enough resources to properly train transit workers for accommodating people with disabilities.

Nancy Jackman, a transit-mobility instructor from Duluth, Minn., helps people with visual or hearing impairments ride transit. But she feels exhausted from the uphill battle. “Transit workers seem very overworked and under-appreciated for the types of problem solving that is demanded,” she reflected.

Public transit is also crucial for essential workers during the pandemic.

Sister Barbara Pfarr, a Catholic nun in Elm Grove, Wis., helps operate a Mother House where sick and elderly sisters reside. But at least half of her food and health-care workers don’t have a driver’s license, she said, and they’re missing shifts due to a lack of transit. As a result, residents in facilities like hers “don’t get their services because their workers can’t get to work, through no fault of their own.”

Barbara is also considering that as she ages, she may also become transit-dependent. “When I’m older and can’t drive anymore, I want to be able to get around.” Many smaller towns and rural areas tend to have disproportionate numbers of older people, and seniors are now outliving their ability to drive safely by an average of 7 to 10 years. Without transit options, many of these seniors will lose their independence.

The hearings also emphasized that survivors of domestic abuse disproportionately rely on transit.

Shivani Parikh, outreach coordinator at the New York State Coalition Against Domestic Violence, testified that a lack of public transit makes it harder for survivors to get help. Service cuts can “greatly influence their sense of isolation, their experience of abuse, and their perceived ability to leave,” she warned.

Throughout America, millions are forced to depend on transit that doesn’t fully meet their needs, while millions more have no access at all. This is unacceptable.

Congress can help. Public transit needs at least $39 billion in emergency relief to avoid service cuts and layoffs through 2023. But more broadly, we need to revise the “80-20” split that’s plagued federal transit funding since the Reagan era — with 80 percent going to highways and less than 20 percent to public transit.

Part of the justification for this disparity is that only people in dense, urban areas use transit. This is upside-down logic. The hearings reveal that when people don’t use transit, it’s because it is nonexistent, unreliable, or inaccessible.

The funding to meet everyone’s transit needs exists — it’s just not being allocated correctly. It’s time we invest in public transit for all of America.

Kayla Soren is a Next Leader at the Institute for Policy Studies.

‘Two harlots screaming’

For what I ate

I feel bad.

My soul aches,

my heart is sad.

In hindsight I whispered,

“Eat neither now,”

but each one I defiled.

I don’t know how,

but alas I did

break my vow.

One was tender,

not hardly ready,

the other laid firm

like a solemn jetty

to buttress the tempest

and craving that be

in the dark depths

at the bottom of me.

Although young then

I was no stranger to fate

I could have left them alone to wait

for their honey to gather slowly within

to forever be as they had been,

but instead they heckled loudly

for “Original Sin”.

They are gone now,

but no virgins were they!

My vulnerabilities

their vexing inflated

I’m worse for that

which I have wasted.

And yet no better satiation

was felt with others I’ve tasted.

How will I tell

my one True-Blue

who keeps our flower

of love in bloom.

Shall I explain how I saw

splayed open like confections

full with lust for my direction,

two harlots screaming

in torrid syncopation

threatening doom

with my least hesitation.

Worse, they warned –

once my passion was unleashed

they would only accept

something “complete.”

It would not be hailed as “True”

until the final consumption

of not one, but two.

These bewitching dollops

would no longer wait.

They settled together

to enjoy their fate.

I savored them each

completely, and slowly,

my glee was immense, my

behavior unholy.

Yes, these flaws I sadly declare.

We mortals are no match

for Sirens in pairs.

Gods can repeat this rule

due to their station,

“Any goddess can adapt

to fit her vexation”.

So now I suffer

throughout my life

with guilt, misgivings

and marital strife

because I was tempted

away from my sacred oath

by two heavenly crumpets,

— and I ate them.

“Confession of a Serial Eater,’’ by William T. Hall, a New England- and Florida-based painter and writer

Maple sugaring means…

Boiling the maple sap in March to make syrup

“Maple sugaring exemplifies the classic New England values of connectness to land and community. Yankee ingenuity, observation of the natural world, heritage pride, entrepreneurship, homespun hospitality, make-do, and can-do, and simplicity.’’

— David K. Leff in Maple Sugaring: Keeping It Real in New England.

Mr. Leff (born 1955), of the Collinsville village in Canton, Conn., is a poet, essayist, lecturer and former deputy commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection.

Some of the Collins Company factory buildings in Collinsville on the Farmington River, viewed from Connecticut Route 179. The company, which closed in 1966, was once the world’s biggest maker of axes. It made other cutting tools, too. The river was the original source of the factory’s power.

A very Vegas vehicle

“Untitled (Las Vegas)” (ink jet print, color xerox, scotch tape), by Matt Williams, in the group show of Mad Oyster Studios at Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass., March 11-April 3.

Llewellyn King: Will classy clothes return after the pandemic?

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a lot of chat about the future of work: Will we do it at home, or will we revert to commuting to the old workplace?

But there is an additional, different question: What will we wear?

Go to the mirror and look at yourself. Except for the odd Zoom meeting you might have tried to dress for, you are a different person.

The fact is that even a traditionalist like me, who has worn a jacket and tie since his first days of school, is, well, letting down.

Worse, after a year of sweats and other baggy, comfortable clothing, I feel constricted and ill at ease when I put on a suit – which is mainly when I record television programs on Zoom or some other video hook-up.

I suspect that you are like me for these Zoom, or the like, formals; you wear a jacket and jeans or exercise pants, hiding your lower half under a table. Notice how cramped you feel above the waist.

Women, do you remember, putting on full makeup -- known in the cosmetic trade as “war paint” – now that you’ve grown accustomed to the au naturel look? Maybe for morale, you wear just a slash of lipstick now and again. Those nice suits in the closet, or flattering dresses, do you remember how confining they were? How hard it was managing that dangling bling?

On that Hallelujah Day when the pandemic is over, will men and women be prepared to get out of those oh-so-comfortable sneakers for Oxfords and pumps?

Was it worth it, yesterday’s clothing? After COVID-19, the way we were isn’t going to be the way it will be. Anyone for going back clotheswise? Or have we been emancipated from wardrobe tyranny and shoe slavery?

There have been various attempts in recent years to dress us down, like Casual Friday. I remember giving a speech at the prestige law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom when they were trying to dress casually all week. The women partners looked miserable; they had made partner, bought Chanel suits, but now they were expected to wear their law school rags. And, oh, the misery of the middle-aged men partners, who had looked to bespoke suits to cover up the expansion of their waists, which had accompanied the collection of fat fees with the advance of age.

The only assault on male fashion before the change agent that is COVID-19 was the abandonment, for reasons unknown, of the poor necktie. What did it do wrong? Let me tell you, no one looks better without them. The naked male throat in a shirt designed for a tie isn’t lovely. Compensation is at hand in a revived interest in the pocket handkerchief or pocket square (which was used for drying the tears of distressed damsels but is used for cleaning one’s eyeglasses in the time of Me Too).

Formality in dress has been under attack for a long time. The tech titans, such as Steve Jobs, and rock musicians were the shock troops. No longer do smart restaurants enforce coats and ties for men and look askance at women in pants. Wearing sweats, shorts, sneakers? “Your table is ready, sir or madam.” Ugh!

Going forward, we may be so casualized in dress that we go to church in pajamas and work in anything that covers the body and is comfortable. The god of comfort has conquered the heavens.

I hope that for the sake of everyone, the fashion mavens, goaded on by the magazines like Vogue and GQ, devise a new era of clothes as comfortable as sweats and as flattering as, well, what we used to wear. Meanwhile, if you know anyone who would like to buy some suits (portly), sport coats (Scottish tweed), and shoes (leather lace-up), have them call me. I’m going to get with the new fashion, where comfort is the only criterion.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

The GOP's un-'well regulated' gun fixation

First muster of the Massachusetts Bay Colonial Militia, spring of 1637

A couple of AR-15s

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It says something about the current state of the gun-obsessed Republican/QAnon Party that Rhode Island’s Republican Conservative Caucus is raffling off firearms, including an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle, to raise money to elect more alleged “conservatives’’ (translation: far-right “populists’’) to the state’s General Assembly.

The quote below is from the then-retired U.S. Chief Justice Warren Burger (1907-1995) in 1990. The Second Amendment interpretation by this true conservative judge was generally the one held by the Supreme Court until far-right appointees of Republican presidents, in league with the gun lobby, began to take over the court. He was chief justice in 1969-1986.

“The Gun Lobby’s interpretation of the Second Amendment is one of the greatest pieces of fraud, I repeat the word fraud, on the American People by special interest groups that I have ever seen in my lifetime. The real purpose of the Second Amendment was to ensure that state armies – the militia – would be maintained for the defense of the state. The very language of the Second Amendment refutes any argument that it was intended to guarantee every citizen an unfettered right to any kind of weapon he or she desires.’’

The Second Amendment:

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.’’

Note that the Founders wrote not only “Militia” but also “well regulated,” in those days before assault rifles….

Cake makes it a party

Julia Child in her kitchen in 1978

“A party without cake is just a meeting.’’

— Julia Child (1912-2004), the very tall, cheery, warbly and down-to-earth American TV personality, cooking teacher and book author whose show The French Chef (1963-1973), produced by WGBH TV in Boston, near her home in Cambridge, became one of the most popular shows in the history of public TV.

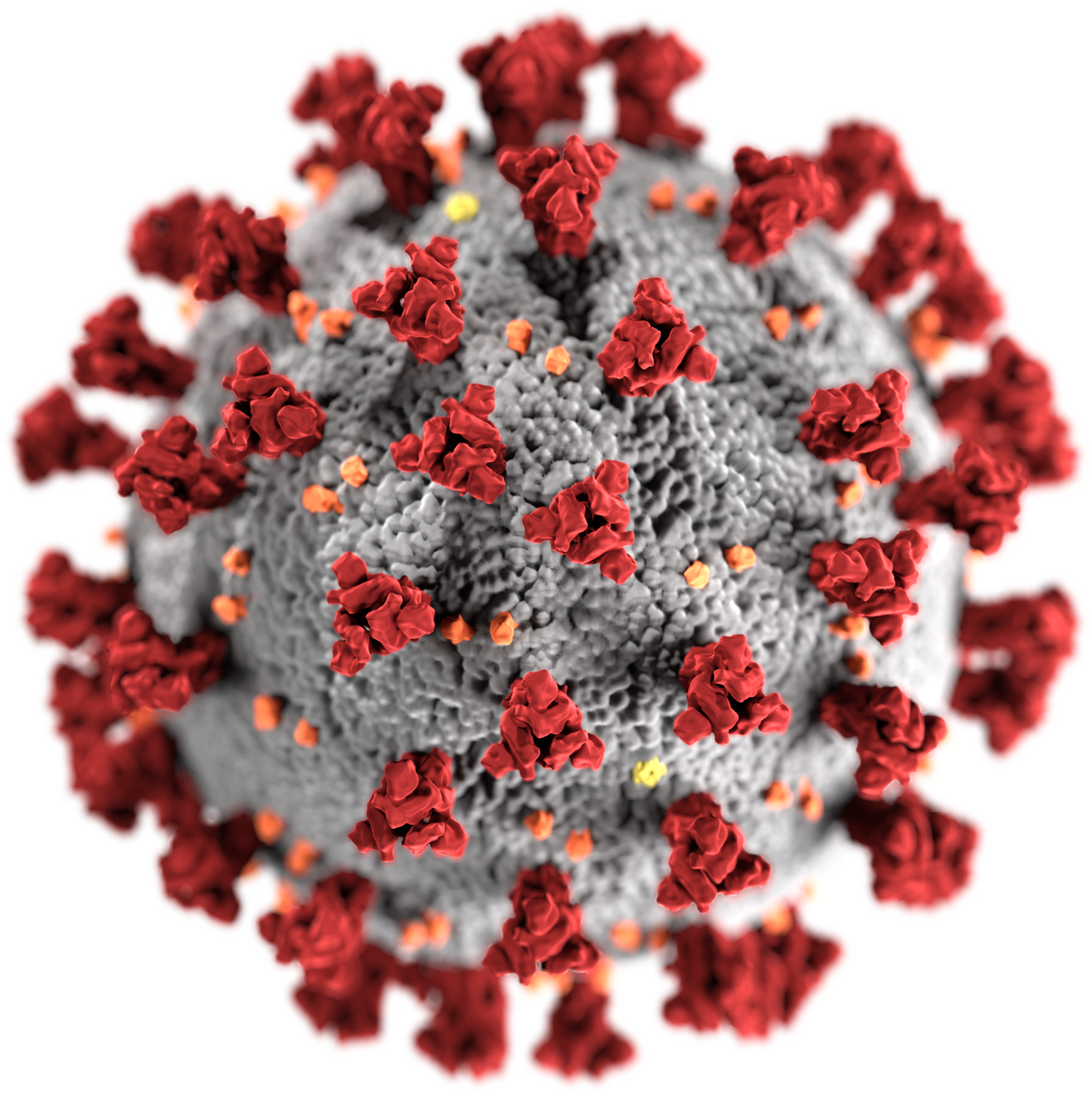

Have one of the COVID-19 variants? They won't tell you

Covid-19 infections from variant strains are quickly spreading across the U.S., but there’s one big problem: Lab officials say that they can’t tell patients or their doctors whether someone has been infected by a variant.

Federal rules around who can be told about the variant cases are so confusing that public health officials may merely know the county where a case has emerged but can’t do the kind of investigation and deliver the notifications needed to slow the spread, according to Janet Hamilton, executive director of the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists.

“It could be associated with a person in a high-risk congregate setting or it might not be, but without patient information, we don’t know what we don’t know,” Hamilton said. The group has asked federal officials to waive the rules. “Time is ticking.”

The problem is that the tests in question for detecting variants have not been approved as a diagnostic tool either by the Food and Drug Administration or under federal rules governing university labs ― meaning that the testing being used right now for genomic sequencing is being done as high-level lab research with no communication back to patients and their doctors.

Amid limited testing to identify different strains, more than 1,900 cases of three key variants have been detected in 46 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s worrisome because of early reports that some may spread faster, prove deadlier or potentially thwart existing treatments and vaccines.

Officials representing public health labs and epidemiologists have warned the federal government that limiting information about the variants ― in accordance with arcane regulations governing clinical labs ― could hamper efforts to investigate pressing questions about the variants.

The Association of Public Health Laboratories and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists earlier this month jointly pressed federal officials to “urgently” relax certain rules that apply to clinical labs.

Washington state officials detected the first case of the variant discovered in South Africa this week, but the infected person didn’t provide a good phone number and could not be contacted about the positive result. Even if health officials do track down the patient, “legally we can’t” tell him or her about the variant because the test is not yet federally approved, Teresa McCallion, a spokesperson for the state department of health, said in an email.

“However, we are actively looking into what we can do,” she said.

Lab testing experts describe the situation as a Catch-22: Scientists need enough case data to make sure their genome-sequencing tests, which are used to detect variants, are accurate. But while they wait for results to come in and undergo thorough reviews, variant cases are surging. The lag reminds some of the situation a year ago. Amid regulatory missteps, approval for a covid-19 diagnostic test was delayed while the virus spread undetected.

The limitations also put lab professionals and epidemiologists in a bind as public health officials attempt to trace contacts of those infected with more contagious strains, said Scott Becker, CEO of the Association of Public Health Laboratories. “You want to be able to tell [patients] a variant was detected,” he said.

Complying with the lab rules “is not feasible in the timeline that a rapidly evolving virus and responsive public health system requires,” the organizations wrote.

Hamilton also said telling patients they have a novel strain could be another tool to encourage cooperation ― which is waning ― with efforts to trace and sample their contacts. She said notifications might also further encourage patients to take the advice to remain isolated seriously.

“Can our investigations be better if we can disclose that information to the patient?” she said. “I think the answer is yes.”

Public health experts have predicted that the B117 variant, first found in the United Kingdom, could be the predominant variant strain of the coronavirus in the U.S. by March.

As of Feb. 23, the CDC had identified nearly 1,900 cases of the B117 variant in 45 states; 46 cases of B1351, which was first identified in South Africa, in 14 states; and five cases of the P.1 variant initially detected in Brazil in four states, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the CDC director, told reporters Wednesday.

A Feb. 12 memo from North Carolina public health officials to clinicians stated that because genome sequencing at the CDC is done for surveillance purposes and is not an approved test under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program ― which is overseen by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ― “results from sequencing will not be communicated back to the provider.”

Earlier this week, the topic came up in Illinois as well. Notifying patients that they are positive for a covid variant is “not allowed currently” because the test is not CLIA-approved, said Judy Kauerauf, section chief of the Illinois Department of Public Health communicable disease program, according to a record obtained by the Documenting COVID-19 project of Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation.

The CDC has scaled up its genomic sequencing in recent weeks, with Walensky saying the agency was conducting it on only 400 samples weekly when she began as director compared with more than 9,000 samples the week of Feb. 20.

The Biden administration has committed nearly $200 million to expand the federal government’s genomic sequencing capacity in hopes it will be able to test 25,000 samples per week.

“We’ll identify covid variants sooner and better target our efforts to stop the spread. We’re quickly infusing targeted resources here because the time is critical when it comes to these fast-moving variants,” Carole Johnson, testing coordinator for President Biden’s covid-19 response team, said on a call with reporters this month.

Hospitals get high-level information about whether a sample submitted for sequencing tested positive for a variant, said Dr. Nick Gilpin, director of infection prevention at Beaumont Health, in Michigan, where 210 cases of the B117 variant have been detected. Yet patients and their doctors will remain in the dark about who exactly was infected.

“It’s relevant from a systems-based perspective,” Gilpin said. “If we have a bunch of B117 in my backyard, that’s going to make me think a little differently about how we do business.”

It’s the same in Washington state, McCallion said. Health officials may share general numbers, such as 14 out of 16 outbreak specimens at a facility were identified as B117 ― but not who those 14 patients were.

There are arguments for and against notifying patients. On one hand, being infected with a variant won’t affect patient care, public health officials and clinicians say. And individuals who test positive would still be advised to take the same precautions of isolation, mask-wearing and hand-washing regardless of which strain they carried.

“There wouldn’t be any difference in medical treatment whether they have the variant,” said Mark Pandori, director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory. However, he added that “in a public health emergency it’s really important for doctors to know this information.”

Pandori estimated there may be only 10 or 20 labs in the U.S. capable of validating their laboratory-based variant tests. One of them doing so is the lab at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Dr. Alex Greninger, assistant director of the clinical virology laboratories there, who co-created one of the first tests to detect SARS-CoV-2, said his lab began work to validate the sequencing tests last fall.

Within the next few weeks, he said, he anticipates having a federally authorized test for whole-genome sequencing of covid. “So all the issues you note on notifying patients and using [the] results will not be a problem,” he said in an email.

Companies including San Diego-based Illumina have approved covid-testing machines that can also detect a variant. However, since the add-on sequencing capability wasn’t specifically approved by the FDA, the results can be shared with public health officials ― but not patients and their doctors, said Dr. Phil Febbo, Illumina’s chief medical officer.

He said they haven’t asked the FDA for further approval but could if variants start to pose greater concern, like escaping vaccine protection.

“I think right now there’s no need for individuals to know their strains,” he said.

Until it isn't

“When Everything is Uncertain, Anything Is Possible” (paper, gesso, watercolor, tape, oil, acrylic, graphite, charcoal, pigment, oil bar on distressed paper, about 13.5 x 7 feet), by Dell Hamilton, at the Brookline (Mass.) Arts Center.

Where politics met commerce

Boston City Hall and Old Suffolk County Courthouse in 1860. It served as City Hall in 1841 to 1865.

Philip K. Howard: Public-employee unions have been a disaster for democracy and the public interest

The NEA is the largest union in the United States.

It’s time to rethink the role of public-employee unions in democratic governance.

Public-union intransigence has contributed to two of the most socially destructive events in the COVID-19 era. Rebuilding the economy after the pandemic ends also will be more difficult if state and local governments have to abide by featherbedding and other artificial union mandates.

Public-employee unions are politically impregnable, but their corrosion of first principles of democratic governance may leave them open to constitutional attack.

The lack of accountability imposed by union contracts has corroded democratic trust. The nearly nine-minute suffocation of George Floyd by Minneapolis policeman Derek Chauvin, every second shown on video, touched off protests around the country and social anger that may impact race relations for years.

But Chauvin should not have been on the job, and he likely would have been terminated or taken off the streets if police supervisors in Minneapolis had had the authority to make judgments about unsuitable officers. Chauvin had 18 complaints filed against him and a reputation for being “tightly wound,” not a good trait for someone carrying a loaded gun.

But police union contracts make it very difficult to terminate officers. Out of 2,600 complaints against police in Minneapolis since 2012, only 12 resulted in any sort of discipline and no officers were terminated. A 2017 report on police abuse nationwide revealed that union contracts make it extremely difficult to remove officers with a repeated history of abuse.

Teachers unions wield similar power. Dismissing a teacher, as one school superintendent told me, is not a process, it’s a career. California ranks near the bottom in school quality but is able to dismiss only two out of 300,000 teachers in a typical year.

Because of COVID-19, teachers unions have adamantly refused to allow teachers to return to work for a year, harming millions of students.

Because many parents can’t work if children are not in school, teachers unions are also impeding our ability to reopen the economy.

Yet most parochial and private schools in the U.S. have reopened, without serious consequences, as have schools in Europe. It is safe to reopen schools, according to the Centers for Disease Control, as long as teachers and students follow certain protocols. Unions now say they’ll put a toe in the water, starting in the spring, when another school year is almost over.

The bottom line is inescapable: Public-employee unions do not serve the public's best interests.

How did public-employee unions turn into public enemies? Until the 1960s, collective bargaining was not lawful in government — it’s hardly in the public interest to give public employees power to negotiate against the public interest.

As President Franklin Roosevelt put it: “The process of collective bargaining… cannot be transplanted into the public service…. To prevent or obstruct the operations of Government …. by those who have sworn to support it, is unthinkable and intolerable.”

Public-employee union power is largely an accident of history, one of the many unintended effects of the 1960s rights revolution. The first shoe to drop was Executive Order 10988, in which President John F. Kennedy, as payback for political support, permitted collective bargaining for federal employees.

Public unions soon demanded similar rights from states. Without any serious debate, New York in 1967 permitted collective bargaining, followed by California in 1968.

Unions gained strength with every new administration. The rhetoric was virtuous: Who can be against the rights of public employees? But the velvet glove of rights barely disguised the political iron fist.

Public employees represent almost 15 percent of the work force, probably the largest organized voting bloc. For more than 50 years, generations of political leaders have promised whatever it would take to get their support, including shields against accountability and rich pensions and benefits. In Illinois, a state now actuarily insolvent, 20,000 public employees enjoy pensions of more than $100,000 per year.

A political solution is almost impossible. Union contracts have long tails, tying the hands of successive political leaders. Their political power also is different from that held by other interest groups; political leaders are powerless without their cooperation.

As labor leader Victor Gotbaum once put it, “We have the ability, in a sense, to elect our own boss.”

Public unions wield this power not just to get benefits, but to dictate how government works. After 80 meetings trying to cajole teachers back to work, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot concluded that “they’d like to take over not only Chicago Public Schools, but take over running the city government.”

Democracy can’t work if elected officials lack the ability to run government. As James Madison put it, democracy requires an unbroken “chain of dependence… the lowest officers, the middle grade, and the highest, will depend, as they ought, on the President.” By shackling political leaders with thick contracts, and eviscerating accountability for cops and teachers, public unions have removed a keystone of democratic governance.

Public unions are not a problem anticipated by the framers of the Constitution. But Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution provides that “the United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government.” Known as “the Guarantee clause,” the provision has never been asserted in this context.

The history of the clause suggests that, by guaranteeing “a republican form of government,” the framers meant to ensure that government would be accountable to voters and not to a monarch or other unaccountable power.

Public unions have severed a key link between voters and governance. They are immune from accountability, collect tribute in the form of featherbedding work rules and excessive pensions, and control what they do day-to-day instead of what voters need.

It is time for a reckoning. The abuses of rogue police, teachers who won’t teach, and other indefensible public union controls cry out for constitutional redress.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, author, civic and cultural leader and photographer, is founder of Campaign for Common Good and chairman of Common Good (commongood.org), a nonprofit legal- and regulatory-reform organization.

His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left.

This column first ran in USA Today.

Full disclosure: The editor of New England Diary, Robert Whitcomb, has collaborated with his friend Mr. Howard in some Common Good projects.

Port Authority Police Benevolent Association, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., a typical small-town police union.

'Far and Near'

Mary Dorsey Brewster (left image) and Warren Jagger (right image) in their joint show , “Far & Near,’’ at the Providence Art Club through March 5.

The future of work and Greater Boston's 'meds and eds'

Downtown Boston: Who will fill those now mostly vacant offices?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Last November, Bill Gates predicted that half of business travel and 30 percent of “days in the office” would disappear forever. Meanwhile, the McKinsey Global Institute says that a mere 20 percent of business travel won’t return and about 20 percent of workers might be working from home indefinitely. Whomever you believe, all this means far fewer jobs at hotels, restaurants and downtown shops, even as the pandemic has speeded the automation of (i.e., killing of) many office jobs (including home office jobs) and more factory jobs.

So what can government do to train people for new, post-pandemic jobs, assuming that there will be many? How can vocational and other schools be brought into this project? The trades – electricians, plumbers, carpenters, roofers, plasterers, etc., will probably have the most secure, and generally well compensated, jobs going forward, along with physicians, dentists and nurses as well as engineers of all sorts and computer-software and other techies.

Another part of the jobs package should be a WPA-style program to rebuild America’s infrastructure, which the drive for lower taxes and higher short-term profits has dangerously eroded. (See Texas again.) This has undermined the nation’s long-term economic health. Such a program could also serve to train many people in new, post-pandemic skills that would be useful even as automation accelerates.

Of course there will always be jobs available for very low-paid personal-help people, such as home health-care workers. Indeed, the aging of the population means that we’ll need a lot more of them

Andrew Yang, an entrepreneur who ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020, made addressing the looming threat of automation-caused job losses a key part of his campaign, which he suspended before the pandemic. He has proposed giving Americans a $12,000-a-year “basic income’’ to help get them through the developing employment implosion. It may come to that….

Meanwhile, “meds and eds’’ – Greater Boston’s (of which Rhode Island is on the edge) dense medical, technological and higher-education complexes – will help save it at least from the worst of the long-term economic disruption caused by the pandemic. Much research must be done by teams in labs; technological breakthroughs require a lot of in-person collaboration, and most college students will continue to want and need in-person teaching. Further, Greater Boston is an international venture-capital and company start-up center. These high-risk activities also require a lot of in-person, look-‘em-in-the-eye work.

On the other hand, Boston’s banks and its famed retirement-investment companies, such as Fidelity, will never have as many employees working in its offices as before COVID-19; nor will its innumerable law firms. Many offices in high rises in downtown Boston (and Providence) will remain empty for a long time while architects, engineers and interior designers try to figure o

The very direct Bette Davis

Bette Davis often played unlikable characters, such as Regina Giddens in The Little Foxes (1941).

“When a man gives his opinion, he’s a man. When a woman gives her opinion, she’s a bitch.’’

xxx

“If you’ve never been hated by your child, you’ve never been a parent.’’

Bette Davis (1908-1989), a mega star of “The Golden Age of Hollywood.’’ Born and educated in Massachusetts, she remained very much a New Englander in manner. Her last husband, out of four, was the actor Gary Merrill, with whom she starred in the famous film All About Eve (1950). They were divorced in 1960 after a decade of marriage after having lived together for much of the 1950s in a mansion in Cape Elizabeth, Maine. After the divorce, she left the Pine Tree State but Mr. Merrill mostly remained there and indeed became very active in Maine politics.

Memorable Davis movie lines:

“What a dump!’’ in Beyond the Forest (1949)

”Fasten your seatbelts; it’s going to be a bumpy night’’ — in All About Eve (1950)

Cape Elizabeth Lights, Cape Elizabeth, Maine

— Photo by Stefan Hillebrand

Roger Warburton: An affordable plan to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions

The shore of Easton’s Point, in Newport. The neighborhood is very vulnerable to flooding associated with global warming.

— Photo by Swampyank

From ecoRI. org

NEWPORT, R.I.

It has been known for sometime that a reduction in greenhouse gases would have significant public-health benefits: less pollution means fewer deaths, fewer emergency room visits, and a better quality of life.

It’s also well known that reducing greenhouse gases would decrease the financial damages from hurricanes and storms, from droughts, and from coastal flooding.

The question, until now, has been: How do we pay for the necessary infrastructure changes?

A recent Princeton University study, Net-Zero America, presents a practical and affordable plan for the United States to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050.

Although it’s a massive effort, the plan is affordable because it only demands expenditures comparable to the country’s historical spending on energy.

“We have to immediately shift investments toward new clean infrastructure instead of existing systems,” according to Jesse Jenkins, one of the project’s leaders.

The plan is also practical, because it uses existing technology. No magic tricks are required.

The plan is also remarkably detailed with analyses at the state and, sometimes, at the county level. For example, the report includes an estimate of the increase in jobs in Rhode Island if the plan were to be implemented.

In nearly all states, job losses in the fossil-fuel industry are more than offset by an increase in construction and manufacturing in the renewable-energy sector.

The motivation behind the recent study is clear: Climate change is “the most dangerous of threats” because it “puts at risk practically every aspect of our material well-being — our safety, our security, our health, our food supply, and our economic prosperity (or, for the poor among us, the prospects for becoming prosperous).”

The challenges are not underestimated: the burning coal, oil, and natural gas supply 80 percent of our energy needs and more than 60 percent of our electricity. Their greenhouse-gas emissions can’t be easily reduced or inexpensively captured and sequestered away.

The plan

The Net Zero America study details the actions required to achieve net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050. That goal is essential to avert the costly damages from the climate crisis.

The study highlighted six pillars needed to support the transition to net-zero:

End-use energy efficiency and electrification/consumer energy investment and use behaviors change (300 million personal electric vehicles and 130 million residences with heat pump heating).

Cleaner electricity (wind and solar generation and transmission, nuclear, electric boilers and direct air capture).

Bioenergy and other zero-carbon fuels and feedstocks (hundreds of new conversion facilities and 620 million t/y biomass feedstock).

Carbon dioxide capture, utilization, and storage (geologic storage of 0.9 to 1.7 giga tons CO2 annually and capture at some 1,000 facilities).

Reduced non-CO2 emissions: (methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorocarbons).

Enhanced land sinks (forest management and agricultural practices).

One of the study’s key findings is that in the 2020s all scenarios create about 500,000 to 1 million new energy jobs across the country. There are net job increases in nearly every state.

The pathways

The plan outlines five distinct technological pathways that all achieve the 2050 goal of net-zero emissions.

The authors don’t conclude which of the pathways is “best,” but present multiple, affordable options. All pathways only require investment and spending on energy in line with historical U.S. expenditures; around 4 percent to 6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). The five pathways are:

High electrification: Aggressively electrifying buildings and transportation, so that 100 percent of cars are electric by 2050.

Less high electrification: This scenario electrifies at a slower rate and uses more liquid and gaseous fuels for longer.

More biomass: This allows much more biomass to be used in the energy system, which would require converting some land currently used for food agriculture to grow energy crops.

All renewables: This is the most technologically restrictive scenario. It assumes no new nuclear plants would be built, disallows below-ground storage of carbon dioxide, and eliminates all fossil-fuel use by 2050. It relies instead on massive and rapid deployment of wind and solar and greater production of hydrogen.

Limited renewables: This constrains the annual construction of wind turbines and solar power plants to be no faster than the fastest rates achieved in the United States in the past but removes other restrictions. This scenario depends more heavily on the expansion of power plants with carbon capture and nuclear power.

In all five scenarios, the researchers found major health and economic benefits. For example, reducing exposure to fine particulate matter avoids 100,000 premature deaths, which is equivalent to nearly $1 trillion in air pollution benefits, by midcentury compared to the “business-as-usual” pathway.

Wind and solar power, along with the electrification of buildings — by adding heat pumps for water and space heating — and cars, must grow rapidly this decade for the nation to be on a net-zero trajectory, according to the study. The 2020s must also be used to continue to develop technologies, such as those that capture carbon at natural-gas or cement plants and those that split water to produce hydrogen.

“The current power grid took 150 years to build. To get to net-zero emissions by 2050, we have to build that amount of transmission again in the next 15 years and then build that much more again in the 15 years after that. It’s a huge change,” according to Jenkins.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: Net-Zero American, E. Larson, C. Greig, J. Jenkins, E. Mayfield, A. Pascale, C. Zhang, J. Drossman, R. Williams, S. Pacala, R. Socolow, EJ Baik, R. Birdsey, R. Duke, R. Jones, B. Haley, E. Leslie, K. Paustian, and A. Swan, Net-Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts, interim report, Princeton University, Princeton, N.J., Dec. 15, 2020.

David Warsh: An old man against the world; don't eat WSJ baloney on Texas crisis

Rupert Murdoch

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Financial Times columnist Simon Kuper chose a good week in which to write about a leading skeptic of climate change. “For all the anxiety about fake news on social media,” Kuper wrote last weekend, “disinformation on climate seems to stem disproportionately from one old man using old media.”

He meant Rupert Murdoch, 89, whose company, News Corp., owns The Wall Street Journal, the New York Post, The Times of London, and half the newspaper industry in Australia. Honored with a lifetime achievement award in January by the Australia Day Foundation, a British organization, Murdoch posted a video:

“For those of us in media, there’s a real challenge to confront: a wave of censorship that seeks to silence conversation, to stifle debate, to ultimately stop individuals and societies from realizing their potential. This rigidly enforced conformity, aided and abetted by so-called social media, is a straitjacket on sensibility. Too many people have fought too hard in too many places for freedom of speech to be suppressed by this awful ‘woke’ orthodoxy.”

There is some truth in that, of course – but not enough to justify the misleading baloney on the cause of crisis in Texas which the editorial pages of the WSJ published last week.

Murdoch is a canny newspaperman, and since acquiring The WSJ, in 2007, he has the good sense not to tamper overmuch with its long tradition of sophistication and sobriety in its news pages. He even replaced the man he had put in charge of the paper, Gerard Baker, after staffers complaints that Baker’s thumb was found too frequently on the scale of its coverage of Donald Trump.

Then again, neither has he tinkered with the more controversial traditions of the newspaper’s editorial opinion pages, to which Baker has since been reassigned as a columnist. The story has often been told about how managing editor Barney Kilgore transformed a small-circulation financial newspaper competing mainly with The Journal of Commerce in the years before World War II into a nationwide competitor to The New York Times, and worth $5 billion to Murdoch. A major contributor to it was Vermont Royster, editor of the editorial pages in 1958–71; and an occasional columnist for the paper for another two decades years after that. He was succeeded by Robert Bartley. Royster died in 1996.

In 1982, Royster characterized the beginnings of the change this way: “When I was writing editorials, I was always a little bit conscious of the possibility that I might be wrong. Bartley doesn’t tend to do that so much. He is not conscious of the possibility that he is wrong.”

Royster hadn’t seen anything yet. With every passing year, Bartley became firmer in his opinions. In the 1990s, his editorial pages played a leading role in bringing about the impeachment of President Clinton. Bartley died in 2002, and was succeeded by Paul Gigot, who has presided over a continuation of the tradition of hyper-confidence. The editorial page enthusiastically supported Donald Trump until the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol.

Last week the WSJ published four editorials on the situation in Texas.

Tuesday, A Deep Green Freeze: “[A[n Arctic blast has frozen wind turbines. Herein is the paradox of the left’s climate agenda: the less we use fossil fuels, the more we need them.”

Wednesday, Political Making of a Power Outage: “The Problem is Texas’s overreliance on wind power that has left the grid more vulnerable to bad weather than before.”

Thursday, Texas Spins in the Wind: “While millions of Texans remain without power for the third day, the wind industry and its advocates are spinning a fable that gas, coal, and nuclear plants – not their frozen turbines – are to blame.”

Saturday, Biden Rescues Texas with… Oil: “The Left’s denialism that the failure of wind power played a starring role in Texas catastrophic power outage has been remarkable”

Then on Saturday, the news pages weighed in, flatly contradicting the on-going editorial-page version of events with a thoroughly reported account of its own, The Texas Freeze: Why State’s Power Grid Failed: “The core problem: Power providers can reap rewards by supplying electricity to Texas customers, but they aren’t required to do it and face no penalties for failing to deliver during a lengthy emergency.

“That led to the fiasco that led millions of people in the nation’s second-most populous state without power for days. A severe storm paralyzed almost every energy source, from power plants to wind turbines, because their owners hadn’t made the investments needed to produce electricity in subfreezing temperatures.”

All three major American newspapers are facing major decisions in the coming year: Amazon’s Jeff Bezos must replace retiring executive editor Martin Baron at The Washington Post; New York Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger presumably will name a successor to executive editor Dean Baquet, who will turn 65 in September (66 is retirement age there); and Murdoch will presumably replace Gigot, who will be 66 in May.

The WSJ editorial page could play an important role in American politics going forward by sobering up. But only if Murdoch – or, more likely, his eldest son, Lachlan, who turns 50 this autumn – selects an editor who writes sensibly, conservatively, about dealing with climate change.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Editor’s note: Both Mr. Warsh and New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, are Wall Street Journal alumni.