'Ambrosial odor'

A sugar shack in late winter or early spring, when maple syrup is made

“{An} ancient wooden shack {stands} among magnificent old maple trees. When we first came in sight of it, it looked as though it were on fire, for the steam from the boiling sap was pouring out through every crack. It was indeed a stirring place — men and boys hallooing in the woods as they chopped fuel for the fire, and drove the sledges down the mountainside with barrels of sap, or ran in and out of the sugarhouse. As we came nearer we caught the ambrosial odor of the steaming syrup.’’

— From The Countryman’s Year (1936), by Ray Standard Baker (1870-1946), writing as David Grayson. A journalist , historian and book author, he moved to Amherst., Mass, in 1910. He lived there for the rest of his life. Among his many jobs was serving as President Wilson’s press secretary during the negotiations for the Treaty of Versailles, in 1919.

He wrote in the book:

“It is not limitation of life that plagues us. Life is not limited: it is the limitation of our awareness of life.”

'Silent, and soft, and slow'

Out of the bosom of the Air,

Out of the cloud-folds of her garments shaken,

Over the woodlands brown and bare,

Over the harvest-fields forsaken,

Silent, and soft, and slow

Descends the snow.

Even as our cloudy fancies take

Suddenly shape in some divine expression,

Even as the troubled heart doth make

In the white countenance confession,

The troubled sky reveals

The grief it feels.

This is the poem of the air,

Slowly in silent syllables recorded;

This is the secret of despair,

Long in its cloudy bosom hoarded,

Now whispered and revealed

To wood and field.

— “Snow-Flakes,’’ by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-82)

Birthplace of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Portland, Maine, c. 1910; the house was demolished in 1955.

Llewellyn King: A prize is needed for ideas on dealing with nuclear waste

Places in Continental United States where nuclear waste is stored

A “scram” is the emergency shutdown of a nuclear power plant. Control rods, usually boron, are dropped into the reactor and these absorb the neutron flux and shut it down.

President Trump, a supporter of nuclear power, has in a few words scrammed the whole nuclear industry, or at least dealt its orderly operation a severe blow.

Scientists see nuclear waste as a de minimus problem. Nuclear-power opponents — who really can’t be called environmentalists anymore — see it as a club with which to beat nuclear and stop its development

The feeling that nuclear waste is an insoluble problem has seeped into the public consciousness. People, who otherwise would be nuclear supporters, ask, “Ah, but what about the waste?”

For its part, the nuclear industry has looked to the government to honor its promise to take care of the waste, which it made at the beginning of the nuclear age.

In the early days of civilian nuclear power — with the startup of the Shippingport Atomic Power Station, in Pennsylvania, in 1957 — the presiding theory was that waste wasn’t a problem: It would be put somewhere safe, and that would be that.

Civilian waste would be reprocessed, recovering useful material like uranium and isolating waste products, which would need special storage. The most worrisome nuclear byproducts are gamma, beta and X-ray emitters, which decay in about 300 years.

The long-lived alpha emitters, principally plutonium, must be put somewhere safe for all time. Plutonium has a half-life of 240,000 years. It’s pretty benign except that it’s an important component of nuclear weapons.

If you get it in your lungs, you’ll almost certainly get lung cancer. Otherwise, people have swallowed it and injected it without harm. It can be shielded with a piece of paper. I have handled it in a glovebox with gloves that weren’t so different from household rubber ones.

But it’s plutonium that gives the “eternal” label to nuclear waste.

Enter President Jimmy Carter in 1977. He believed that reprocessing nuclear waste — as they do in France, Russia, Japan and other countries — would lead to nuclear proliferation. Just months in office, Carter banned reprocessing: the logical step to separating the cream from the milk in nuclear waste handling.

Since then, it’s been the policy of succeeding administrations that the whole, massive nuclear core should be buried. The chosen site for that burial was Yucca Mountain, in Nevada. Some $15 billion to $18 billion has been spent readying the site with its tunnels, rail lines, monitors and passive ventilation.

In 2010 Sen. Harry Reid (D-Nev.) — then the majority leader in the Senate — said no to Yucca Mountain. It’s generally believed that Reid was bowing to casino interests in Las Vegas, which thought this was the wrong kind of gamble.

The industry had pinned all its hopes on Yucca Mountain being revived under Trump: He had promised it would be. Then on Feb. 6, and with an eye to the election (he failed to carry Nevada in 2016), Trump tweeted, “Nevada, I hear you and my administration will RESPECT you!

In the Department of Energy, which was promoting Yucca Mountain, gears are crashing, rationales are being torn up and new ones thought up, even as the nuclear waste continues to pile up at operating reactors. No one has any idea what comes next.

Time, I think — after watching nuclear-waste shenanigans since 1969 — to take a very fresh look at nuclear- waste disposal. Most likely, a first step would be to restart reprocessing to reduce the volume.

I’ve been advocating that to leave the past behind, a prize, like the XPRIZE — maybe one awarded by the XPRIZE Foundation — should be established for new ideas on managing nuclear waste. The prize must be substantial: not less than $20 million. It could be financed by companies like Google or Microsoft, which have lots of money, and a declared interest in clean air and decarbonization.

The old concepts have been so tinkered with and politicized that nuclear waste is now a political horror story. Make what you will of Trump being on the same side of nuclear-waste management as presidents Carter and Barack Obama.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Containers or low-level nuclear waste

Campus expansionism

On the Brown campus

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Brown University wants to build two dorms, housing a total of 375 undergraduate students, at the southern end of its main campus, on Providence’s College Hill. This would require tearing down three undistinguished houses, a small commercial strip and a police substation, all properties owned by Brown.

Presumably there would be some pushback from neighbors concerned about, for example, even tighter parking on neighborhood streets, which are increasingly monopolized by Brown-connected people, but I’d be very surprised if the project didn’t happen. Colleges and universities, especially rich “elite’’ ones such as Brown, are constantly trying to expand and they usually get their way.

Despite the complaints that Brown doesn’t pay property taxes (it does fork over some payments in lieu of taxes to the city -- $6.7 million a year at last count) and more generalized complaints about its power and huge footprint, the fact is that its presence, along with that of the Rhode Island School of Design, are key factors in making the College Hill/East Side of Providence so attractive. Brown has some facilities and activities that local residents can enjoy; it ensures that there are many physicians and other health-care professionals (and the Brown teaching hospitals they help staff) and other useful experts close by, and includes a large, generally beautiful, almost parklike campus – a lovely amenity to have near the middle of a city. Indeed, some of those complaining all the time about Brown live on the East Side/College Hill because Brown is there, whether or not they work there

An old joke is that “Providence is Fall River with Brown.’’ Well, as a state capital and former industrial and foreign-trade center, it was always much more than that, but certainly Brown has had something to do with keeping Providence viable as a mid-size city as its old industrial base shrank. Brown’s expansion is, all in all, good for the city, though taxpayers would like it to chip in more money in lieu of taxes. And no, I didn’t go to Brown.

In general, having a college or university brings wealth and energy to their hosting communities, albeit with some irritations and costs.

To read more about Brown’s latest expansion plans, please hit this link.

A Nantucket origin story

Nantucket from a satellite. Martha’s Vineyard’s Chappaquiddick Island is on the left.

“Look now at the wondrous traditional story of how this island {Nantucket} was settled by the red-men. Thus goes the legend. In olden times an eagle swooped down upon the New England coast, and carried off an infant Indian in his talons. With loud lament the parents saw their child borne out of sight over the wide waters. They resolved to follow in the same direction. Setting out in their canoes, after a perilous passage they discovered the island, and there they found an empty ivory casket --the poor little Indian's skeleton.’’

-- From Moby-Dick (1851), by Herman Melville (1819-91)

Chris Powell: Conn. Democrats' hypocrisy on military spending

Connecticut's members of Congress, all Democrats, are upset -- some almost apoplectic -- about President Trump's using his emergency power to divert military appropriations away from nuclear submarine and jet-fighter procurement to help finance the wall he is having built along the border with Mexico.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal says, "This is about appealing to President Trump's political base" -- as if in opposing the diversion the senator and his colleagues in Connecticut's delegation aren't appealing to their political base, the military contractors and subcontractors in the state that make submarines and jet fighters.

Sen. Chris Murphy says, "The president is stealing money from programs that keep us safe during real national emergencies to fund his stupid border wall." But how persuasive is any member of Congress from a military contracting state like Connecticut when he is just defending appropriations for his own constituents? Has any member of Congress from Connecticut ever opposed an appropriation for military contracting that was to have been spent in the state?

As for keeping the country safe during "real national emergencies," how about that "emergency" with Afghanistan, now in its 20th year? How many more years of that "emergency" will be required before Connecticut's congressmen acknowledge that it is not an "emergency" at all but just another discretionary war of nation building, less of an emergency than the illegal immigration Trump's border wall addresses?

To his credit Murphy lately has led the effort to stop the president from waging war on Iran without the approval of Congress. But the long war in Afghanistan, having achieved nothing but death, seems to have escaped the senator's notice. Where is the legislation to terminate appropriations for that war? Why does that war keep getting a pass from Connecticut's delegation, if not because of the delegation's reluctance to jeopardize the state's military contracting?

Besides, the delegation shares the blame for diversion of the sub and jet-fighter money. For politics is compromise, the president's discretion to move military money around in emergencies he declares and defines has been the law for many years, and Democrats have yet to want much compromise with Trump over illegal immigration.

Indeed, most leading Democrats in Connecticut want as much illegal immigration as they can get, since it proletarianizes the country, increasing the population's dependence on government welfare programs, and increases the number of Democratic-leaning legislative districts, since illegal immigrants cluster overwhelmingly in Democratic urban areas, where, though they aren't supposed to vote, they still are counted toward formation of new congressional and state legislative districts.

That is, the more illegal immigrants, the more Democrats in Congress and the General Assembly.

Silly as the Democrats consider the border wall, by appropriating directly for it and giving Trump what he wanted they might have guaranteed their wildest dreams of military contracting and even have achieved at last the naturalization of the innocent young people, the "Dreamers," brought into the country illegally by their parents and now living in limbo. But blocking immigration law enforcement comes first for Connecticut Democrats, even ahead of more weapons.

Somehow the country will manage with fewer jet fighters and subs, especially if Congress goes beyond posturing against a hypothetical war and terminates one that is only too real.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Staring at 'nonspectacular' flora

“Inside/Outside’’ (oil on canvas) , by Maria Napolitano, in her March 2-May 3 show “Garden Fragments,’’ at Periphery Space at Paper Nautilus, Providence. She explains:

“The work in this show invites you to stop and take a closer look at the ordinary and non-spectacular flora that surround most of our lives. To do this, I mix up painterly, cartoony and diagrammatic approaches which I use to draw attention to the fragile relationship we have with our ecosystem. Whether it be based on the dried remnants of last year’s garden or visual memories I collect from a winter walk in the park, I combine observation and imagination to provide an insight into my everyday interaction with nature. “

Try trains again

Providence’s infamous stuck-up bridge over the Seekonk River

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary’’ in GoLocal245.com

Architectural historian and critic William Morgan’s recent entertaining GoLocal column with zany ideas (ski jump!) on what to do with the abandoned railroad bridge over the Seekonk River at the head of Narragansett Bay served to remind many of us that a light-rail line from Providence down through East Providence, Barrington, Warren and Bristol would make a lot of sense. And maybe it could eventually be extended across to Aquidneck Island via a railroad bridge next to the Mount Hope Bridge.

After all, it’s a densely populated strip with distinct town centers (for stations). It would make a lot of environmental and economic sense to lay down the line even if that meant putting it where the East Bay Bike Path (formerly a rail route!) is now. You can move a lot more people by train than by bike, and do it in all weather.

In any event, we need to better knit together the improving post-industrial waterfront of East Providence with Providence’s eastern shore.

To read Mr. Morgan’s column, please hit this link.

Maybe Mr. Morgan could do another essay on Providence’s “Superman Building,’’ this one with some fantastical suggestions – e.g., hanging gardens, a recirculating waterfall, an aviary at the top….

Hit this link to read his last column on that Art Deco skyscraper.

Racism left out of history books

“Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta, ‘‘ from "Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated)" (offset lithography and silkscreen on Somerset Textured paper), a show by Kara Walker, at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, through April 19.

The museum says: “Kara Walker is New York-based artist whose work has appeared worldwide, tackling complex social issues such as race, gender, sexuality and violence. She's known for her use of silhouetted figures in her prints. In “Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated),’’ she combines her signature prints with enlarged woodcut plates from the book Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War to illustrate a different side of the Civil War: the perspective of African Americans of the era and the racism they experienced that were left out of history books.

Don Pesci: Using Conn. tolls as an escape hatch

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont threw up his hands in a gesture of surrender and took a pause in his ceaseless efforts to rig Connecticut with a new revenue source – tolls – so that his comrades in the General Assembly would not have to apply themselves diligently during the next decade to balancing chronic deficits through spending cuts. A new revenue source would buy progressives in the legislature about ten years of business-as-usual slothfulness. It is their real hedge against spending reductions.

“I think it’s time,” Lamont said at a hastily called news conference, “to take a pause” and -- he did not say -- to resume our tireless efforts next year, after the November 2020 elections have been put to bed. The specter always hanging over the struggle for and against tolls always has been the upcoming elections, when all the members of Connecticut’s General Assembly will come face to face with the voter’s wrath. The prime directive in state politics is to get elected and stay elected, without which all ideas, hopes, dreams, and the vain strutting of one’s hour upon the political stage, are evanescent puffs of smoke.

“Gov. drops tolls plan” ran the front page, above the fold headline in a Hartford paper, underscored with a sub-headline, “Democratic Senate leaders are still open to a vote on controversial legislation.” The word “controversial” in that headline is a massive understatement. The best laid toll plans of Lamont and leading Democrats in the General Assembly were torn asunder by a volcanic eruption of disgust and dismay that Speaker of the House Joe Arsimowicz and President of the Senate Martin Looney seem convinced will disappear within the following year. Their experts no doubt have counseled them that the lifespan of political memories in Connecticut is exceedingly short; by November, all the Sturm und Drang over tolls will have been dumped onto the ash heap of ancient history.

No one will recall these bitter fighting words from Lamont, “If these guys [Lamont’s Democrat co-conspirators who had been giving him assurances that there were enough votes in the General Assembly to pass his re-worked toll plan] aren’t willing to vote and step up, I’m going to solve this problem. Right now, we’re going to go back to the way we’ve done it for years in this state when we kept kicking the can down the road."

By the expression “kicking the can down the road” Lamont meant to indicate that the Democratic-dominated legislature and preceding governors had not, unlike him, attacked transportation issues, not to mention massively dislocative state workers’ pension obligations, with energy and dispatch. We are back to borrowing money to pay for transportation and road repair because – Lamont did not say – his Democrat comrades in the General Assembly had in the past raided dedicated funds, transportation funds among them, in order to move from laughably insecure “lockboxes” to the General Slush Fund monies necessary to patch massive holes in budget appropriations and expenditures caused by inordinate spending.

The real political division in Connecticut is not, and perhaps never has been, between Democrats and Republicans. The dissevering line runs between progressive politicians who, victims of their own past successes, are not discomforted by ever-increasing taxes and spending – which go together, like the proverbial horse and carriage – and those who are beginning to suspect that the usual political bromides only sink the state further in a mire of political corruption and anti-democratic but successful political verbiage that makes no sense when examined closely. In the post income tax period, Connecticut entered into a perilous and fatally repetitious Groundhog Day, and those who might have opened the eyes of the public, reporters and commentators, were fast asleep.

Tolls are, in fact, an escape hatch for politicians who want to deceive their real employers, voters, into swallowing the fiction that less money for the masses and more for the politicians will usher in a progressive Eden, whereas inordinate revenue infusions only relieve politicians of the brutal necessity for spending cuts.

The general perception among all groups opposed to tolls and other revenue boosters appears to be: not one cent more in net revenue. For the benefit of the real state, not Connecticut’s administrative apparatus, the General Assembly must show in an indisputable and public manner that it intends to inaugurate real, lasting, spending reforms. The General Assembly is making a serious political mistake if it assumes that all the ruckus of the past year surrounding tolls is only about tolls. It is about the General Assembly and present and past governors who have closed their eyes and ears to the havoc they have caused and the wounds and injuries they have visited upon our beloved state.

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based columnist.

'Left with yourself'

Inman Square in Boston

— Photo by Tim Pierce

“Just to be in Boston, in Cambridge, on a Monday night was very horrifying to me. It frightens me . . . All the stores closing up by 5 or 6, coffeehouses being open maybe until 11, just the sense that the world shuts down and you're left with yourself.”

― Ann Douglas, English professor emerita at Columbia who got her PhD at Harvard

An objective approach

“Who’s on First” (oil on canvas), by Madolin Maxey, in her March 8-27 show, “Objects as Narrative,’’ at the Providence Art Club. In it, she uses objects from her studio “in settings that lead to visual conversations with the viewer.’’

Trashy art in Maynard

Work by Mary Mooney, in the show “Out of the Box,’’ at ArtSpace Maynard (Mass.) through April 18.

The gallery says:

“ArtSpace Maynard artists challenged each other to create art from collections of trash and treasure that were boxed and re-distributed to participating artists at random. This challenge has brought artists in this community together to commiserate and encouraged them to step into entirely new territory with their work.’’

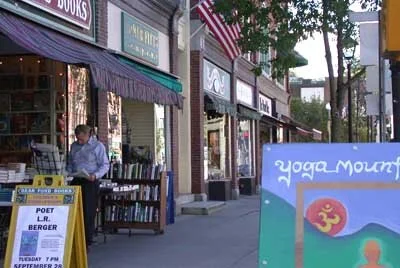

Maynard is located on the Assabet River, a tributary of the Concord River. A large part of the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge is within the town.[2]

Historic downtown Maynard, above, hosts many shops, restaurants, galleries, a movie theater, and the former Assabet Woolen Mill, which produced wool fabrics from 1846 to 1950, including cloth for Union Army uniforms during the Civil War. Maynard was the headquarters for Digital Equipment Corporation, one of the first big computer companies, from 1957 to 1998.

Kayak and canoe launch dock at Ice House Landing, on the Assabet River, Maynard.

Trump's planned 'classical' command

Two “Modernist’’ landmarks: the “Brutalist” Boston City Hall, ugly (to many people). Below, the Hancock Tower in Boston, which most people (I think) find beautiful.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The White House is considering putting out an order called “Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again’’ that would mandate “classical’’ styles as the default design for all new federal buildings in Greater Washington, D.C., and for all new federal buildings everywhere, including courthouses, projected to cost more than $50 million each.

Now, a lot of “classical’’ architecture is attractive in its dignified, symmetrical, solid way, and some modern architecture, especially the Brutalist (think Boston City Hall) and Deconstructivist (think the Seattle Central Library and the Stata Center at MIT), hideous to many, but not all, people. (The order would ban both styles.) Some “classical’’ architecture can look silly, with columns looking pasted on in an effort to make a building appear Graeco-Roman (and instant old); or they can recall sterile, heavy Stalinist or even Nazi-era creations.

But many people (including me) find some modern architecture gorgeous. Consider the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington or the federal courthouse in downtown Los Angeles.

The selection of architects, and of the many other people involved in getting public buildings up, should depend on their appreciation of beauty (modified by functional needs and budgetary constraints) of design and quality of materials, whatever the style. And public buildings should look as if they’re going to stand for a long, long time, as we hope (more nervously these days) the country will. Why circumscribe creativity as much as Trump wants to do? There’s a lot of it out there.

Classic “classical’’ — The National Archives, in Washington, D.C.

Phil Galewitz: Trump's Medicaid chief mostly wrong on its outcomes, access

“This wouldn’t pass muster in a first-year statistics class.’’

— Benjamin Sommers, health-care economist at Harvard, of Medicare-Medicaid chief’s remarks

The Trump administration’s top Medicaid official has been increasingly critical of the entitlement program she has overseen for three years.

Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, has warned that the federal government and states need to better control spending and improve care to the 70 million people on Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for the low-income population. She supports changes to Medicaid that would give states the option to receive capped annual federal funding for some enrollees instead of open-ended payouts based on enrollment and health costs. This would be a departure from how the program has operated since it began in 1965.

In an early February speech to the American Medical Association, Verma noted how changes are needed because Medicaid is one of the top two biggest expenses for states, and its costs are expected to increase 500% by 2050.

“Yet, for all that spending, health outcomes today on Medicaid are mediocre and many patients have difficulty accessing care,” she said.

Verma’s sharp comments got us wondering if Medicaid recipients were as bad off as she said. So we asked CMS what evidence it has to back up her views.

A CMS spokesperson responded by pointing us to a CMS fact sheet comparing the health status of people on Medicaid to people with private insurance and Medicare. The fact sheet, among other things, showed 43% of Medicaid enrollees report their health as excellent or very good compared with 71% of people with private insurance, 14% on Medicare and 58% who were uninsured.

The spokesperson also pointed to a 2017 report by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), a congressional advisory board, that noted: “Medicaid enrollees have more difficulty than low-income privately insured individuals in finding a doctor who accepts their insurance and making an appointment; Medicaid enrollees also have more difficulty finding a specialist physician who will treat them.”

We opted to look at those issues separately.

What About Health Status?

Several national Medicaid experts said Verma is wrong to use health status as a proxy for whether Medicaid helps improve health for people. That’s because to be eligible for Medicaid, people must fall into a low income bracket, which can impact their health in many ways. For example, they may live in substandard housing or not get proper nutrition and exercise. In addition, lack of transportation or child care responsibilities can hamper their ability to visit doctors.

Benjamin Sommers, a health economist at Harvard University, said Verma’s comparison of the health status of Medicaid recipients against people with Medicare or private insurance is invalid because the populations are so different and face varied health risks. “This wouldn’t pass muster in a first-year statistics class,” he said.

Death rates, for example, are higher among people in the Medicare program than those in private insurance or Medicaid, he said, but that’s not a knock on Medicare. It’s because Medicare primarily covers people 65 and older.

By definition, Medicaid covers the most vulnerable people in the community, from newborns to the disabled and the poor, said Rachel Nuzum, a vice president with the nonpartisan Commonwealth Fund. “The Medicaid population does not look like the privately insured population.”

Joe Antos, a health economist with the conservative American Enterprise Institute, also agreed, saying he is leery of any studies or statements that evaluate Medicaid without adjusting for risk.

For a better mechanism to gauge health outcomes under Medicaid, experts point to dozens of studies that track what happened in states that chose in the past six years to pursue the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion. The health law gave states the option to extend Medicaid to everyone with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level, or about $17,600 annually for an individual. Thirty-six states and the District of Columbia have adopted the expansion.

“Most research demonstrates that Medicaid expansion has improved access to care, utilization of services, the affordability of care, and financial security among the low-income population,” concluded the Kaiser Family Foundation in summarizing findings from more than 300 studies. “Studies show improved self-reported health following expansion and an association between expansion and certain positive health outcomes.” (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

Studies found the expansion of Medicaid led to lower mortality rates for people with heart disease and among end-stage renal disease patients initiating dialysis.

Researchers also reported that Medicaid expansion was associated with declines in the length of stay of hospitalized patients. One study found a link between expansion and declines in mechanical ventilation rates among patients hospitalized for various conditions.

Another recent study compared the health characteristics of low-income residents of Texas, which has not expanded Medicaid, and those of Arkansas and Kentucky, which did. It found that new Medicaid enrollees in the latter two states were 41 percentage points more likely to have a usual source of care and 23 percentage points more likely to say they were in excellent health than a comparable group of Texas residents.

Medicaid’s benefits, though, affect far more than the millions of nondisabled adults who gained coverage as a result of the ACA. “Medicaid coverage was associated with a range of positive health behaviors and outcomes, including increased access to care; improved self-reported health status; higher rates of preventive health screenings; lower likelihood of delaying care because of costs; decreased hospital and emergency department utilization; and decreased infant, child, and adult mortality rates,” according to a report issued this month by the nonpartisan Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Children — who make up nearly half of Medicaid enrollees — have also benefited from the coverage, studies find. Some studies report that Medicaid contributes to improved health outcomes, including reductions in avoidable hospitalizations and lower child mortality.

Research shows people on Medicaid are generally happy with the coverage.

A Commonwealth Fund survey found 90% of adults with Medicaid were satisfied or very satisfied with their coverage, a slightly higher percentage than those with employer coverage.

Accessible Care?

The evidence here is less emphatic.

A 2017 study published in JAMA Internal Medicine found 84% of Medicaid recipients felt they were able to get all the medical care they needed in the previous six months. Only 3% said they could not get care because of long wait times or because doctors would not accept their insurance.

Verma cites a 2017 MACPAC report that noted some people on Medicaid have issues accessing care. But that report also noted: “The body of work to date by MACPAC and others shows that Medicaid beneficiaries have much better access to care, and much higher health care utilization, than individuals without insurance, particularly when controlling for socioeconomic characteristics and health status.” It also notes that “Medicaid beneficiaries also fare as well as or better than individuals with private insurance on some access measures.”

The report said people with Medicaid are as likely as those with private insurance to have a usual source of care, a doctor visit each year and certain services such as a Pap test to detect cervical cancer.

“Medicaid is not great coverage, but it does open the door for health access to help people deal with medical problems before they become acute,” Antos said.

On the negative side, the report said Medicaid recipients are more likely than privately insured patients to experience longer waiting times to see a doctor. They also are less likely to receive mammograms, colorectal tests and dental visits than the privately insured.

“Compared to having no insurance at all, having Medicaid improves access to care and improves health,” said Rachel Garfield, a vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “There is pretty strong evidence that Medicaid helps patients get the care they need.”

Our Ruling

Verma said that “health outcomes today on Medicaid are mediocre and many patients have difficulty accessing care.”

Numerous studies show people’s health improves as a result of Medicaid coverage. This includes lower mortality rates, shorter hospital stays and more people likely to get cancer screenings.

While it’s hard to specify what “many patients having difficulty accessing care” means, research does show that Medicaid enrollees generally say they have no trouble accessing care most of the time.

We rate the claim as Mostly False.

Phil Galewitz is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Phil Galewitz: pgalewitz@kff.org, @philgalewitz

Gridlocked in the Depression

Downtown Boston in 1932, in the Great Depression. You might not guess unemployment was over 20 percent! But then, Will Rogers said at the the time:

“We are the first nation in the history of the world to go to the poor house in an automobile. ‘‘

2d Amendment art

“Revolver 14’’, by Corey Pickett, in the group show “Either I Woke Up, or Come Back to This Earth,’’ at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier.

The gallery says: “These artists use playfulness and humor to challenge histories of political violence and the anesthetic of nostalgia.’’

The Vermont State House, in Montpelier, the smallest state capital, which has only about 8,000 residents. It’s surprisingly arty and has a strong culinary scene, too. It hosts the New England Culinary Institute, which runs some local restaurants.

In downtown Montpelier

Montpelier in 1884

Russ Olwell: Early college programs are way for New England colleges to avoid demographic disaster in years ahead

At Merrimack College, a private Augustinian college in North Andover, Mass. It was founded in 1947 by the Order of St. Augustine with an initial goal to educate World War II veterans. The college has grown to encompass a 220-acre campus and almost 40 buildings. North Andover is both a Boston suburb, high end in some places, and also a former mill town. It also hosts the Brooks School, a fancy boarding school.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

This photograph on top from Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker’s State of the Commonwealth address last month shows more than just happy college students in their sweatshirts. These students, from Northern Essex Community College and Merrimack College, are part of cohorts of students who have graduated from “early college” programs (with up to a year’s college credit) and successfully matriculated into a two- or four-year college. Recipients of the Lawrence Promise Scholarship at the Haverhill-based (but multi-site) Northern Essex Community College and the Pioneer Scholarship at Merrimack College, these students are on track to graduate on time, and can serve as mentors and role models to young people in their families and in their neighborhoods—proof that college is a real possibility.

Why are these students so important?

The students in the picture, and graduates of similar programs, offer a chance to avoid a demographic crash that faces higher education nationwide (but hits hardest in New England). This is most strikingly laid out in Nathan Grawe’s book Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education, which uses survey data and mathematical modeling to predict the future of higher education. For two-year institutions, regional four-year institutions and all but the top 50 colleges nationwide, the news in Grawe’s book is grim: The decline in childbirths in the wake of the Great Recession of 2008-9 will reverberate into the 2020s and 2030s. This will lead to fewer high school graduates, and fewer students with the family background and finances to propel them into traditional college enrollment.

Grawe considers a full range of possibilities to counteract this curve, such as changes in state higher- education policy, that could increase the proportion of students who might attend colleges, and reduce the racial gaps in groups attending college. In Grawe’s analysis, however, none of these policy tools will close the gap enough to save many higher-education institutions from closing, or from a stark decline in students and revenue.

What can change the curve?

The Commonwealth can try to bend this curve by increasing the number of students who aspire to go to college, and who have the skills to enroll and graduate. One such intervention, which has the potential to scale to the state level, is early college programming, in which high school students are able to take college coursework during the K-12 experience, in order to learn to successfully navigate the college world. Through success in college classes, these students stop thinking of college as a possibility, and instead as something they know they can do.

Early college programs have been a success story in American education, raising enrollments and enhancing student outcomes. Early college programs can help low-income and underrepresented students gain access to higher education and be more successful students once they arrive to college full time, according to research by David R. Troutman, Aimee Hendrix-Soto, Marlena Creusere and Elizabeth Mayer in the University of Texas System.

Early college programs (high school students attending college courses on campus) have shown great impact on academic achievement of students, net return on investment, and graduation rates of participating students.

In successful programs and statewide efforts, students thrive in these programs, are more likely to attend college and are remarkably more successful once they get to campus full time. They are more likely to graduate on time than their peers who attend traditional high schools, and earn a higher GPA.

Recent studies released by American Institutes of Research found the economic return of investment on early college programs to be $15 in benefit for every $1 investment; the U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse recently certified the results of a random-assignment early college study that showed a positive impact in such key metrics as school attendance, number of school suspensions, high school graduation, college enrollment and earning a college credential.

New England has been a growing force in the early college field. Massachusetts now is home to at least 30 designated early college partnerships; Maine has created early college programs for its state four-year colleges, community college and maritime academy; and New Hampshire has launched a STEM-focused early college effort centered on career-technical education and the community college system. While these are far smaller than the efforts in Texas and North Carolina, they are making a positive impact and appealing to a broad range of families.

Scaling and expanding access

Early college programs have not been easy to expand or spread. First, like most successful policy interventions, they are hard to scale without losing the power of the model. The best early college programs are often about 400 students in size, run by dedicated instructors and leadership. Maintaining a size where each student can connect with at least one adult in the building is one of the keys to this work.

This model is hard to scale statewide, which is what would need to happen to have any meaningful impact on the downward curve of college applicants. Early college programs can also suffer from elitism. They can attract smart, ambitious, well-off students and families, leaving behind the populations that can be helped the most by the model. As college costs drive more behavior across the economic spectrum, middle-class and upper middle-class parents will see early college programs as a lifeline, and could seek out opportunities that had previously been designed for lower-income families. In my earlier work in Michigan, I saw programs start to fill up with the children of professors at the college housing the early college, as it was seen to be such a bargain.

However, as early college is embraced by new states and regions, policymakers are paying more attention to making sure that programs can grow, and can retain the characteristics that make the model so effective. As new programs are developed in Massachusetts, there is renewed emphasis on reaching the at-risk students who could be most helped by this intervention. With a push to help all students in a high school leave with some college credit, the impact of early college programs on student enrollment could counteract economic and social barriers to enrollment, moving whole cohorts of students into higher education.

In order for any of the above to have an impact on college enrollment a decade from now, state policy and spending will need to shift, investing in areas such as early college that can help students be successful in college from day one. Most importantly, early college programs and their impact would need broader recognition and support, and would need to be embraced by a wider range of K-12 and higher education leaders than have supported it to date. It might take today’s downward facing enrollment curve to get the attention of policymakers, who up until now have regarded early college with a mix of curiosity and suspicion. To save higher education in Massachusetts, we need more students up in the balcony, graduating from high school with college credit, ready to help their younger peers make the same good decisions.

Russ Olwell is a professor and associate dean in the School of Education and Social Policy at Merrimack College.

— Photo by NAThroughTheLens

An aerial view of the North Andover Old Center showing the North Parish of North Andover Unitarian Universalist Church.

Our coyote co-existence

Coyote calling for company

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘In its Feb. 14 article, “Valentine’s Day Is Also for Coyotes,’’ The Boston Guardian warn us that February marks the start of coyote mating season. Yes, there are plenty of opportunistic coyotes in Boston, including downtown, and in Providence and Worcester. The beasts become more skittish and territorial in mating time, and more likely to attack other animals, including people, at this time of the year. As mankind takes over more and more of the world, many creatures will have to learn -- like, for example, coyotes and raccoons – how to live close to humans, or go extinct.

![Maynard is located on the Assabet River, a tributary of the Concord River. A large part of the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge is within the town.[2]Historic downtown Maynard, above, hosts many shops, restaurants, galleries, a movie theater, …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/561446cce4b094b629347f8d/1582495301748-51FIXPMKGG9YL860ZQ9Y/500px-Nason_Street_in_downtown_Maynard_Massachusetts_MA_USA_with_the_Maynard_Outdoor_Store.jpg)