Honor Ms. Quimby's gift

"The Knife Edge'' atop Mt. Katahdin.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary'' column in GoLocal24.com

Maine Gov. Paul LePage, a very Tea Partyish politician, has asked President Trump to reverse President Obama’s designation of 87,500 acres given by businesswoman Roxanne Quimby to the National Park Service as the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument. Presidents have long had considerable power to protect such federally owned scenic and otherwise important areas by designating them as National Monuments.

Mr. LePage, an entertainingly grumpy Republican elected twice by a minority of voters because of Maine’s hoary tradition of having strong third-party candidates, wants the acreage to be returned to private ownership and opened for big recreational developments, resort hotels, snowmobilers and so on.

It would be nice if Mr, LePage, et al., would focus on economic development on, say, the vast expanses of vacant parking lots around empty big box stores.

That could despoil a gorgeous area just to the east of Baxter State Park, where rises spectacular Mt. Katahdin, the highest mountain in the Pine Tree State at 5,267 feet. (I have climbed it and walked along the Knife Edge at the top. Bring your anti-vertigo pills if you try it!)

Let us hope that President Trump respects Ms. Quimby’s intentions and the precedent that presidents have the authority to set aside such land.

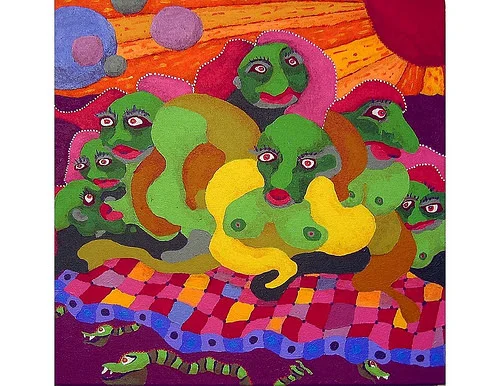

They only look friendly

Work by David Dauer, in his show at Colo Colo Gallery, New Bedford, Mass., through March 2.

David Warsh: Kenneth Arrow, a kindly giant of economics

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Kenneth Arrow died last week, at 95, as modestly as he lived. He had survived his economist wife of 70 years, Selma Schweitzer Arrow, by 18 months. Of what I read in the obituaries, the most telling glimpse was one that his son David afforded the Associated Press.

“He was a very loving, caring father and a very, very humble man. He’d do the dishes every night and cared about people very much. I think in his academic career, when people talk about it, it often sounds like numbers and probabilities. But a large focus of his work was how people matter.’’

Arrow’s nephew, former Treasury Secretary, Harvard University president, and himself an economist, Lawrence Summers, also provided an intimate view.

The next most germane observation could be ascribed to many persons over the years: if Nobel Prizes were awarded solely to recognize dominant contributions to economic theory, the Stanford University economist would have won four or five. As his friend Paul Samuelson once said, he was the foremost economic theorist of the second half of the twentieth century.

Arrow’s eminence is frequently ascribed, James Tobin-fashion (“don’t put all your eggs in one basket”) to the short summary of social choice, a sub-discipline he and Duncan Black more or less founded in 1948 (“No voting system is perfect”). But he also fundamentally shaped the price theory applications, decision making under uncertainty, growth economics and the economics of information.

Indeed, with his appropriation of the terms “moral hazard” and “adverse selection” from the insurance industry (he trained one summer to be an actuary), Arrow introduced psychology and strategy into a fledgling science that to that point had understood itself as the study of prices and quantities.

He later sought, without success, to rename the problems he had identified as those of “hidden action” and “hidden information.” But the deed was done. After the appearance of “Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care,” in 1963, economics gradually came to concern itself with the information differences that are absolutely ubiquitous in life – and with the incentives they create.

Arrow’s centrality to the present age is not well understood. My Web site, Economic Principals, among many others, has worked away on it for years. Among his contributions, perhaps the least known, is what happened after he moved to Harvard University from Stanford, in 1968.

Since the late 19 Century, Harvard had long been, with Columbia University and the University of Chicago, one of three main centers of economic learning in the United States. With the Russian Revolution and rise of Nazi Germany, Princeton became a late starter after 1933.

After the loss of two brilliant graduates to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – Paul Samuelson, in 1940, Robert Solow, in 1950 – the Harvard economics department entered a long period of relative decline. Excellent faculty (Howard Raiffa, Thomas Schelling, Hendrik Houthakker, for example) continued to attract excellent students (Vernon Smith, Robert Wilson, Richard Zeckhauser, Samuel Bowles, Thomas Sargent, Christopher Sims, Robert Barro among them, and, by extension, Fischer Black) but not the critical mass of National Science Foundation grant recipients who flocked to MIT.

The latter would become the rising generation; familiar names today include Robert Merton, Joseph Stiglitz, Robert Hall, Eytan Sheshinski, George Akerlof, William Nordhaus, Martin Weitzman, Stanley Fischer, Robert Shiller, Paul Krugman, Ben Bernanke, and Jean Tirole. Relating the history of the Harvard department from its founding to the outbreak of World War II, Prof. Edward Mason pleaded with his editors, toward the end of the article, to permit him to delay the writing of the next chapter “until we are up again.”

By the early 1960s, Harvard economics had sloughed off the methodological conservatism and residual anti-Semitism that had cost it ITS leadership 20 years before. After losing a third brilliant graduate, Franklin Fischer, to MIT, the university resolved to reverse the course of events (about the same time they bet big on molecular biology). Successive chairmen John Dunlop and Richard Caves, hired three Clark Medal winners – Arrow (1957), Zvi Griliches (1965), and Dale Jorgenson (1971) – tenured Martin Feldstein, and brought John Meyer back from Yale (and, with him, from Manhattan, the National Bureau of Economic Research).

During the next 11 years, Arrow (and fellow theorist Jerry Green) taught many of the leaders of the generation that initiated the revolution in information economics. They included Michael Spence, Elhanan Helpman, Eric Maskin, Roger Myerson, Jean-Jacques Laffont, and John Geanakoplos (not to mention scores of stellar undergraduates, including Jeffrey Sachs, James Poterba, and Robert Gibbons). Feldstein taught Summers and dozens of others. Harvard once again was among the top departments, this time in the world – especially after Maskin returned from MIT, followed by several others. Someone will write up the story of those remarkable years someday.

All the while, Arrow returned to Stanford every summer, to preside over conferences at the Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences, organized by Stanford professor Mordecai Kurz. It was at the IMSSS that many developments of the next generation took place. By 1980, Arrow was ready to return to Stanford. But that’s a story for another day.

After he left, Harvard University Press published six volumes of his collected papers – Social Choice and Justice; General Equilibrium; Individual Choice under Certainty and Uncertainty; The Economics of Information; Production and Capital; and The Economics of Information.Earlier, he had published a volume of papers on planning written with his friend Leo Hurwicz, Studies in the Resource Allocation Process.

In 2005, Arrow attached an addendum to his autobiography on the Nobel Foundation site, to reflect a subtly changing reappraisal, his own and that of others, of the significance of his work. In 2009, he became founding editor, with Timothy Bresnahan, of The Annual Review of Economics. And in recent years, he began thinking of the next volumes of collected papers – perhaps as many as another six or even eight, including one on economics and ecology. Much more time will be required to see Kenneth Arrow in perspective.

David Warsh, a veteran financial journalist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

From grand house to greenie inn, with maybe a speakeasy along the way

The Stone House, in Little Compton, R.I.

-- Photo by Lydia Davison Whitcomb

The Stone House, a gorgeous inn on Sakonnet Point, in the bucolic town of Little Compton, R.I., is like many such establishments in summer resort communities on the New England coast: It started as a large private house.

The four-story structure was built in 1854 by David Sisson, an iron and textile manufacturer as New England’s Industrial Revolution really got cooking. It was also home to his son Henry Tillinghast Sisson, a Civil War hero and Rhode Island lieutenant governor in 1875-77.

The house became an inn in the early 20th Century. In its basement is a very cozy and inviting tap room, rumored to have been a speakeasy during Prohibition, where you can now have meals as well as drinks. The booze for the speakeasy might well have been offloaded from lobster boats sent out a few miles offshore to pick it up from distributors. Lots of cat and mouse with the Coast Guard.

The Stone House is on the National Registry of Historic Places but it also has some green technologies, including heating and cooling systems that rely on geothermal technology.

Robert Whitcomb: 1938's vast wine-pine-lumber surplus

Forest damage after the 1938 Hurricane.

Thirty-Eight: The Hurricane That Transformed New England, by Stephen Long (Yale University Press) 272 pages, as various prices.

This piece first ran in The Weekly Standard.

When I was a boy living in coastal Massachusetts, I frequently heard stories about the great hurricane that crashed into Long Island and New England on Sept. 21, 1938. Most of the people who described it to me—my father and some of his friends—were only in their 30s and early 40s when they told me about it, and had very vivid stories, especially after a few drinks. What the 1906 earthquake is to San Francisco, the 1871 fire is to Chicago, and Hurricane Katrina is to New Orleans, the '38 Hurricane (aka "The Long Island Express'') is to New England and Long Island.

Seeking relief from my humdrum world, I once longed to experience such an event. What I didn't appreciate at the time was how long the mess and inconvenience from such a storm could last—in the case of the '38 storm, for decades in some places. Given the scale of the catastrophe in one of the most populous and richest parts of the country, the 1938 Hurricane at first got surprisingly little attention from the rest of the country because attention was riveted on the Munich crisis; many assumed that war was about to break out in Europe. (Of course, that wouldn't be for another year.) But the storm killed around 700 people and destroyed many buildings, bridges, and miles of road. Its tidal surge altered long stretches of the southern New England and Long Island coasts.

Stephen Long clearly and dramatically, and sometimes with droll humor details the mayhem produced by torrential rain followed by winds that gusted to nearly 200 miles an hour on Blue Hill, south of Boston. He serves up a mix of regional history, meteorology, botany, ecology, politics, economics—all seasoned with anecdotes. But his book is mostly about the trees that the storm took down, especially in New England's large and well-established second-growth forests and in "the pastoral combination of farm field and forest [that] adorned'' the region, interspersed by villages with steepled white churches. That's the (unrepresentative) scene that many tourists most associate with the region; the storm's massive blowdowns (including of steeples) altered the views in many places.

As a boy, I saw evidence of this damage in the woods next to our house, where there were numerous pits where the roots of uprooted trees had been. From the pits' shape you could tell which direction the strongest wind came: from the southeast, at more than 100 miles an hour. And there were still many gaps in the woods where tall trees had once stood. Long, founder and former editor of Northern Woodlands magazine, focuses on the ecological, economic, and sociological effects of the storm's destruction of mature trees in a wide swath of New England.

"The roaring wind toppled forests in every New England state," he writes, "with New Hampshire and Massachusetts [east of the eye of the storm] hit particularly hard. The path of destruction spanned ninety miles across.'' And "70 percent or more of the toppled timber was Pinus strobus—eastern white pine''—the most valuable and vulnerable tree crop in New England because of its height, straightness, and its many uses, from lumber to houses, furniture, and cheap shipping boxes. All this devastated many landowners, already brought low by the Great Depression, who depended on pine sales from their wood lots to make ends meet. Also torn up were many maple-tree stands, the sap from which provided a lot of extra income to New England farmers and other landowners. Long writes accessibly about why certain trees sustained far more damage than others: "The taller the tree the longer the lever and the greater force it can exert on the ground where it's anchored.'' Trees on southeast-facing slopes were particularly vulnerable.

Enter the Roosevelt administration, in an example of what perhaps only government can do: clean up damage from natural disasters that extends over many square miles. Much praise was due the U.S. Forest Service as well as FDR's Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in responding to a disaster as huge as the '38 Hurricane.

The first imperative, state and federal officials and an anxious public thought, was to reduce the chances of massive forest fires from the downed, and thus drying, trees and branches. Indeed, some of the forests were closed to the public for long stretches after the hurricane for fear of fire. That the hurricane had made many of the firewatch towers inaccessible—roads were blocked by fallen trees—made it that much scarier. And so, Long explains, federal officials, led by the Forest Service, pulled together the resources of various organizations, but especially thousands of otherwise unemployed men working for the CCC (young men) and the WPA (which had older men as well). They opened roads and helped clean out much of the

But what to do with the fallen timber taken out of the woods, which could flood the market and lower the already-low price of the wood? To address this issue, the federal government invaded the private market with a vengeance: "The Forest Service saw the need for a stabilizing influence on the price of logs and the flow of lumber to market," Long writes, "so it put the power of the federal government to work'' by establishing "a fair price for logs,'' buying up all it could, and then gradually selling it as "demand required." At the heart of this reasoning was that the purchasing program would allow thousands of local landowners to realize a decent return from what could have been a nearly total economic loss. The cost of the salvage program was $16.3 million (in 1938 dollars), of which 92 percent was recovered by the government.

It's doubtful that such market intervention by government will happen after the next big hurricane blows through, but then, Roosevelt saw the hurricane response as another way of fighting the Depression. The cleanup also showed, in private-public collaborations, just how good Americans can be at addressing an emergency—as they were soon to prove after Pearl Harbor. A lot of that hurricane wood was used in war-related products and, later, in the postwar building boom.

Meanwhile, with the continuing disappearance of farmland, New England is now more forested than at any time in the past 200 years. Some year, the Northeast will again have a record surplus of lumber on the ground after another huge hurricane. And we may even long for another CCC and WPA.

Robert Whitcomb is editor of New England Diary.

Vt. might embrace some GOP-style healthcare changes

Looking toward Mt. Mansfield, the summit of Vermont.

— Photo by K. Kemerait

From Cambridge Management Group (cmg625.com)

Paradoxically, generally Democratic Vermont (but now with new Republican Gov. Phil Scott) could be setting the pace for some of the healthcare reforms touted by by the Trump administration and the Republican Congress.

The Green Mountain State won got a broad federal waiver last October to redesign how its healthcare is provided and paid for. This includes new payment systems, a stepped-up effort to prevent unneeded treatments, cutting overall growth in the cost of services and drugs, and more effectively dealing with such public-health problems as opioid abuse.

The six-year initiative follows a failed effort under former Democratic Gov. Peter Shumlin to adopt a single-payer plan for all residents.

The hope is that the program eventually will involve 70 percent of the state’s population, almost all of its 16 hospitals and 1,933 physicians and would include patients covered through their employment as well as those in Medicare and Medicaid.

Med City News noted that while the Obama administration approved the experiment it “fits the Republican mold for one way the Affordable Care Act could be replaced or significantly modified. The Trump administration and lawmakers in Congress have signaled that they want to allow states more flexibility to test ways to do what Vermont is doing — possibly even in the short-term before Republicans come to an agreement about the future of the ACA.”

T0 read more please hit this link.

Tracy Hassett: Can New England colleges collaborate to cut costs?

Tuition prices at colleges and universities are high. On that, pretty much everyone—from parents to students to college administrators—can agree. It’s also true that salaries and benefits are the single biggest chunk of every higher education institution’s (HEI) budget. And one of the largest and most difficult costs to contain is group employee health insurance. In fact, health insurance represents on average 4% to 5% of the total operating budgets at most private HEIs in New England.

The situation is particularly difficult for smaller New England HEIs because they don’t have the power to bargain with commercial insurers enjoyed by, say, MIT or Harvard. They are forced to fend for themselves in negotiating for benefit packages, whose costs—including all benefits paid for by the employer and employee—have increased on average 20% over the past five years.

Yet, colleges and universities are under increased scrutiny to create efficiencies and bring costs under control. Some institutions are doing that by hiring more part-time workers, to avoid the expense of offering a full-time benefits package. Others have begun limiting the number and kind of benefits packages they offer or passing along more of the cost to employees. Still others are trying something relatively new in higher education—collaborating on health insurance benefits.

Collaboration is not new to HEIs. The key benefit of collaboration is to shift risk away from a single HEI experimenting with a new approach and providing a broader proof of concept with less risk. In a report by the Davis Educational Foundation (DEF) in November 2012, there was widespread appreciation for the work of the educational consortia in New England—the Association of Vermont Independent Colleges, the Boston Consortium, Colleges of the Fenway, Five College Consortium, New Hampshire College and University Council and the Worcester Consortium—for their efforts to increase collaboration, share faculty and staff, and reduce procurement, health and other insurance expenses and other common cost areas. It was suggested that future DEF grants should encourage more sharing and collaboration.

In the same report, “The cost of providing medical insurance was uniformly mentioned [by presidents of HEIs] as a growing concern. The increase in premiums continues to pressure already constrained operating budgets and there appears to be no end in sight.”

Thanks to a grant from the DEF and investment by 22 other institutions, the Collaborative Educational Ventures of New England (CEVoNE) was formed. Of those 22 institutions, six created a startup called Educators Health (edHEALTH), building on the collaboration model. EdHEALTH currently comprises a dozen small and mid-sized education institutions, which own and govern the organization. Instead of reducing benefits and limiting plans, these institutions, which may be competing for students, are collaborating on controlling healthcare costs. The schools contract with traditional insurers for the administrative work, but instead of paying claims from a commercial insurer, they are paid our of pooled resources, thus spreading the risk.

EdHEALTH is an independent organization with members who are also in the Boston Consortium, the Higher Education Consortium of Central Massachusetts, and the Association of Independent Colleges of Rhode Island.

There are some early metrics to suggest that in this particular case, the collaboration model seems to be working, although overcoming some initial skepticism from administrators wasn’t easy.

Due to the usual institutional aversion to change, many HEIs decided to take a wait-and-see approach until edHEALTH “proved” itself. In addition, several finance administration officials expressed serious concerns about taking on the financial risk of self-insuring their employee healthcare.

Health insurance impacts almost all employees and their families and is a significant recruiting tool. From the beginning, it was not easy to get new colleges to become members/owners. HR officials were particularly worried about any disruption their employees might see, such as having to change doctors, health plan designs, or increasing their share of health insurance premiums.

HR professionals were also concerned about losing control over plan designs and the ability to use their own independent broker/consultant and health insurance carriers. Not all brokers are supportive of their clients joining edHEALTH, as their own compensation may decrease. As a result, many brokers/consultants may not have the institutions’ best interest in mind as they consider and recommend alternatives to the rising cost of employee healthcare to prospective member institutions.

Now three years in, edHEALTH can allay many of the concerns. A total of 12 HEIs in two states have become members/owners of edHEALTH including: Berklee College of Music, Boston College, Brandeis University, Emerson College, Lasell College, Olin College of Engineering, Regis College, Salve Regina University, Wellesley College, Wentworth Institute of Technology, Wheaton College, and Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

Our members have learned that as owners of the collaboration, they determine the plan designs. Furthermore, all the schools who joined edHEALTH with a broker/consultant have maintained the relationship with their individual brokers/consultants.

From a financial perspective, the average yearly premium rate increase for edHEALTH members from 2015 to 2017 was just 3.5% versus industry average increases of 6% to 9% per year. This has translated into savings of over $25 million in just three years for the HEIs and the employees. In fact, since edHEALTH’s inception, HEIs have retained $4.5 million in savings that would have otherwise ended up in the hands of insurance companies. Furthermore, edHEALTH paid the full $1.2 million back to all 22 of the CEVoNE members who invested $50,000 each to see edHEALTH come to fruition.

During this time when the future of the Affordable Care Act is in question, edHEALTH is an example of a collaborative and innovative effort taking shape. While collaboration takes time, there is strong evidence that it is necessary to bend the trend in the rising costs of and within higher education.

Tracy Hassett is president and CEO of Educators Health. This piece first ran on the Web site of the New England Board of Higher Education (nebbe.org).

Fresh out of the drier

"Nitty Gritty'' (wood, plastic and lint), by Carl McMahon, in her show "Specimentos,'' at the Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through March 26.

Lauren Owens Lambert: Trying to rescue sea turtles on Cape Cod beaches.

A Kemp's Ridley sea turtle.

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org

Winters are harsh on the shores of Cape Cod. They’re not a place where you would expect to find tropical sea turtles. But each winter, greens, loggerheads and Kemp’s Ridleys wash up, stunned by the cold ocean temperatures and disoriented by the unfamiliar geography.

Tony LaCasse, of the New England Aquarium, calls the hook-like shape of the geography “The Deadly Bucket.”

With help from volunteers and biologists at Mass Audubon and the New England Aquarium, the turtles are rescued, rehabilitated and flown to warmer waters to be released. Turtle strandings averaged about 90 annually until 2014, when there was a record 700.

The most commonly found stranded species is also the most endangered, the Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle.

“We are not sure why we are seeing an increase in strandings while also noticing an overall decline in population of ridleys,” said Connie Merigo, director of the New England Aquarium’s Marine Animal Rescue Program, one of the oldest programs of its kind in the country.

Sea turtles are some of the world’s great navigators, but for this part of their journey a little help is needed.

Massachusetts resident Lauren Owens Lambert runs a photo journalist Web site.

'Inches away'

"The sun is brilliant in the sky but its warmth does not reach my face.

The breeze stirs the trees but leaves my hair unmoved.

The cooling rain will feed the grass but will not slake my thirst.

It is all inches away but further from me than my dreams."

--- M. Romeo LaFlamme, ''The First of March''

Breakthrough

On this weekend, snowdrops push through last year's oak leaves in a Connecticut yard.

Photo by THOMAS HOOK

Not yet nursing homes

“Another historical peculiarity of the place was the fact that its {New England town's} large mansions, those relics of another time, had not been reconstructed to serve as nursing homes for that vast population of comatose and the dying who were kept alive, unconscionably, through trailblazing medical invention.”

John Cheever, from Oh What a Paradise It Seems

While Cheever lived much of his life in New York City and Westchester County, N.Y., just to the north of it, he remained almost obsessed by where he had grown up on Greater Boston's South Shore.

'Besides his reason'

"Tinsel in February, tinsel in August.

There are things in a man besides his reason."

-- Wallace Stevens

Overused consultants

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary'' column in GoLocal24.com

The bungled rollout of Rhode Island’s new public-benefits computer system, a launch whose primary vendor was Deloitte Consulting, raises some questions about how much governments should depend on private-sector contractors that may not understand the complexities of creating or revising systems to serve the general public. There have been many other rather similar bungled launches by state governments, with those in Vermont, Kentucky and Oregon among the most dramatic screw-ups.

Sometimes it may make much more functional and financial sense to have government employees do the jobs now being done by consultants, assuming that the political leadership obtains adequate resources for training them and indeed hires more state employees to ensure that a new system is properly managed over coming years. Many in the public complain that Rhode Island government is overstaffed. It is not.

What can go wrong in hiring outside consultantsto do jobs that are more properly those of government employees was vivid in Iraq, where after the U.S. invasion in 2003, the Bush administration sent in thousands of very highly paid consultants(some being employees of consultancies with political connections) to do what military and other federal employees should have been doing. As a result, there were scandals involving inappropriate physical force as well as vast cost overruns and administrative snafus.

Sometimes hiring outside consultants to do government work can be a great big fat false economy.

It was good to hear Gov. Gina Raimondo again take ultimate responsibility the other week for the mess; she has removed some of the state executives who had been involved in the launch.

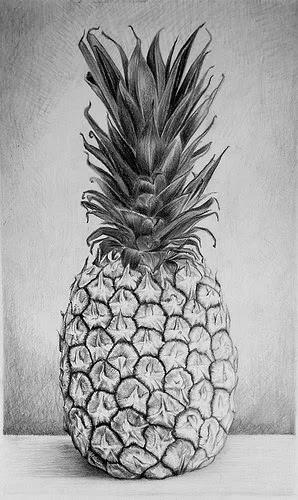

The welcome fruit

"Pineapple'' (graphite on bristol board), by Hillary Irvine, in the show "Fresh,'' at the Rocky Neck Art Colony, in Gloucester, Mass., through March 12. The pineapple has long been a symbol in New England of welcome, which is odd since we don't grow them here (maybe in a few years we can....)

Retail rage

Overheard in Providence's Macy's yesterday: one rather small and effeminate young man loudly denouncing a big and bearded colleague thus: "You make working here nearly impossible!''

Chris Powell: Suburbs prosper by zoning out the poor; coercion by liberals is quite all right; sanctimony cities

Old County Jail Museum in semi-bucolic Tolland, Conn.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Chest-thumping is resounding in Connecticut's suburbs as Gov. Dannel Malloy proposes to transfer their state financial aid to the cities. The thumping may be loudest in Tolland, where at a Town Council meeting the other day Town Manager Steve Werbner pandered to a standing-room-only audience.

Werbner said: "They've taken a town like Tolland, which has done every thing right for many years, and penalized us for all that we've done."

Tolland is a great town but what it and many other suburbs have done "right" has been mainly to zone out the poor and dysfunctional by minimizing cheap apartments, figuring that this way the burden of the slob culture coddled by the welfare system could be confined to the cities forever.

Not anymore. With the governor's budget the government and welfare classes are cannibalizing the state even though taxpayers are tapped out. This cannibalizing is being done in the name of alleviating poverty, though for more than half acentury Connecticut's cities have only manufactured poverty.

The failure of state poverty policy to achieve its nominal objective has made it hard to blame the suburbs for zoning out the poor. But at last the suburbs may have to answer financially for their indifference to that failure. Maybe the suburbs now will discover that doing "everything right" requires them to start holding the poverty factories and their enablers to account.

xxx

For weeks the left, especially inConnecticut, where it is led by Governor Malloy, has been indignantly insisting that the federal government should not try to coerce states and municipalities into helping to enforce federal immigration law, as President Trump wants them to. On immigration the political left, especially in Connecticut, has taken a state's rights position and even a nullification position.

So what happened last week when the Trump administration adopted its own states' rights position, withdrawing Obama administration "guidelines" directing states to allow male students who want to be female and female students who want to be male to use whichever gender's bathroom they choose?

The left freaked out that the federal government now will leave the bathroom issue to the states, though there is no federal legislationspecifically addressing the point, as there is with immigration. Governor Malloycalled the federal action "outrageous." It seems that coercion by the government must be reserved for enforcing a liberal agenda and nobody else's.

xxx

People from 50 churches around Connecticut and New York who gathered last weekend at a synagogue in Hamden seemed to think that God wants the UnitedStates to have no immigration law. According to the New Haven Register, they discussed not only how to protect ordinary illegal immigrants against deportation but also even illegal immigrants who have been criminally convicted.

The event's organizer, Rabbi Herbert Brockman, of Hamden's Congregation Mishkan Israel, quoted Leviticus from the Old Testament: "When a stranger resides with you in your land, you shall not wrong him."

People from 50 churches around Connecticut and New York who gathered last weekend at a synagogue in Hamden seemed to think that God wants the UnitedStates to have no immigration law. According to the New Haven Register, they discussed not only how to protect ordinary illegal immigrants against deportation but also even illegal immigrants who have been criminally convicted.

The event's organizer, Rabbi Herbert Brockman of Hamden's Congregation Mishkan Israel, quoted Leviticus from the Old Testament: "When a stranger resides with you in your land, you shall not wrong him." So is any immigration law enforcement necessarily doing wrong? Besides, just how much moral authority does Leviticus retain when its very next chapter, not quoted by the rabbi, demands the murder of homosexuals?

The immigration issue is complicated. It involves not just what to do with the estimated 11 million people who have broken into the country illegally or stayed here illegally, and their innocent children, but also preserving the country's secular and democratic culture, which some immigrants abhor and want to destroy. It also involves justice for the low-skilled native-born facing greater competition for jobs, and the value, if there is to be any, of citizenship itself. The meeting in Hamden displayed the faction in the controversy that refuses to acknowledge all these issues. In pursuit of sanctuary cities, this faction is giving the country sanctimony cities.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn., and a frequent contributor to New England Diary.

The fate of the oceans

To members and friends of the Providence Committee on Foreign Relations (thepcfr.org; pcfremail@gmail.com).

Our next guest will be Dr. Stephen Coan, on Wednesday, March 8

Dr. Coan is president and chief executive officer of Sea Research Foundation, Inc., a 501c3 non-profit organization which operates Mystic (Conn.) Aquarium, Institute for Exploration and Immersion Learning. He is also chief executive officer of The JASON Project, an internationally acclaimed science program for classroom students, also managed by Sea Research Foundation in partnership with the National Geographic Society.

He’ll talk about the condition and future of the oceans in a time of global warming and other environmental challenges, especially the manmade ones.

Then:

Brazilian political economistand commentator Evodio Kaltenecker willspeak on Thursday, March 16, about the challenges and opportunities for that huge nation as well as conditions in South America’s Southern Cone – Uruguay, Argentina and Chile.

On Wednesday, April 5, famed French journalist, novelist and broadcaster Jean Lesieur will speak on the global order being turned upside down by the advances of dictators, the retreat of democracies and the presidency of Donald Trump, not tomention the existential crisis of the European Union.

Dr. Rand Stoneburner, the international epidemiologist, is now scheduled to speak on Wednesday April 19. He’ll talk about Zika, Ebola and other global health challenges.

James E. Griffin, an expert on ocean fishing and other aspects of the global food sector, will speak to us on Wednesday, May 17.

David Shear, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Asian and Pacific Security Affairs, under the Obama administration, will speak to us on Thursday, June 1. (He is leaving office of Jan. 20, 2017.) He previously served as United States Ambassador to Vietnam. He was also formerly deputy assistant secretary for East Asian and Pacific affairs at the U.S. Department of State. He’ll talk about Chinese expansionism in the South China Sea, North Korea and other Asia/Pacific topics.

Joining us on Wednesday, June 14, will be Laura Freid, CEO of the Silk Road Project, founded and chaired by famed cellist Yo-Yo Ma in 1998, promoting collaboration among artists and institutions and studying the ebb and flow of ideas across nations and time. The project was first inspired by the cultural traditions of the historical Silk Road.

Meanwhile, we’re trying to keep some flexibility to respond to events. Everything in human affairs is tentative. ”We make plans and God laughs….’’

Suggestions and contacts are always appreciated!

'Balanced on a human scale'

The Lyme, N.H., green (a few months from now).

"When people who have never lived in New Hampshire or Vermont visit here,

they often say they feel like they've come home. Our urban centers, commercial

districts, small villages and industrial enterprises are set amid farmlands and

forests. This is a landscape in which the natural and built environments are

balanced on a human scale. This delicate balance is the nature of our

'community character.' It's important to strengthen our distinctive, traditional

settlement patterns to counteract the commercial and residential sprawl that

upsets this balance and destroys our economic and social stability."

~- Richard J. Eward, from "Proud to Live Here'' {the Upper Connecticut River Valley}

Dangerous mission

In his show at the Maud Morgan Fine Arts Chandler Gallery, in Cambridge, Mass., Mr. Bergstein shows how he has used his studio floor as "an archaeological site in which to explore my own mind."

The gallery says that "For over a decade, he has added paint and collage to an ever-evolving studio installation that serves as a figurative and literal starting point for his artwork. The pieces ... combine photographs of his studio collage with additional visual elements, intentionally blurring the lines between photography, painting and collage.''

Self-exploration can be the most traumatic exploration of all.