Month of meteorological mood disorders

"It was one of those March days when the sun shines hot and the wind blows cold: when it is summer in the light, and winter in the shade."

-- Charles Dickens

David Warsh: Newspaper truths and movie truths

Spotlight, about The Boston Globe’s 2002 series of stories that put an end to efforts by the Archdiocese of Boston to cover up over the years the behavior of pedophile priests, won the Oscar for best picture. But no matter who won the best picture Oscar at the Academy Awards last night, 2015 was a goodyear for topical flicks. Spotlight was a brilliant success. So was The Big Short.

Both translate important news stories into Hollywood vernacular.

Spotlight viewers have often applauded at the end of showings; some left the dark in tears.

The Big Short tells how in 2006 three disparate groups of investors sought to bet against big mortgage lenders, and how, despite their ingenuity, they failed to make as much money and/or fame as they hoped they might. Running commentary, their own and others, on the cupidity of Wall Street provides counterpoint to the bittersweet saga. People leave the theater laughing and shaking their heads.

Each movie drives home important truths. Predatory priests wreak havoc on young lives. The hierarchy of the Catholic Church in Boston defended its pedophile priests’ immunity from the criminal justice system until The Globe undertook an all-out reporting campaign to overturn its indifference.

Mortgage lending in the U.S. and elsewhere went crazy after 2003, but the market stayed manic longer than the film’s prescient short-sellers were able to maintain their bets that it would fall. Only several months after they got out did the market crash.

But there’s movie truth and newspaper truth. What follows is newspaper truth.

***

Spotlight depends for its drama on the fiction that a chasm separating darkness from light existed between Globe editors and reporters who worked for the Taylor family in the 1990s and the paper under management sent in 2001 by its new owner, the New York Times Co.

In fact, two successive Globe editors in the ’90s, John S. (Jack) Driscoll and Matthew V. Storin, gradually turned the stories of various local pedophile priests, James R. Porter, John R. Hanlon, and John J. Geoghan in particular, from short items about lawsuit filings tucked away well back in the paper’s Metro section into front-page news. In each case they were reacting to the efforts of crusading attorneys. They were gingered along the way by various Globe reporters, including Alison Bass, Daniel Golden, James Franklin and David Armstrong; by reporter Kristen Lombardi, of the Boston Phoenix; and by Globe columnist Eileen McNamara.

As early as 1993, Cardinal Bernard Law had called down “the power of God” on The Globe , as he sought to downplay the newspaper’s reports of priestly misconduct. By 2000 he had himself been accused of protecting a notorious pedophile. By the next spring it had become public knowledge. By the summer of 2001, the story was simmering just below the boiling point.

That’s where the movie begins, as a new editor arrives at The Globe. Martin Baron (played in the film by Liev Schreiber), a highly skilled news editor, is fresh in from the frontlines of watchdog journalism in Florida as chief editor of The Miami Herald (the Elián González custody battle, the contested 2000 presidential election vote count). He’s also an outsider to Boston, untrammeled by the tribal loyalties of the city. He quickly recognizes that there is more to the story of priestly abuse than had been made of it so far. So starting his first day on the job, he turns up the heat.

He assigns the story to the Spotlight Team, the pioneering investigative unit The Globe had created 30 years before, led by Globe veteran Walter (Robby) Robinson (portrayed in the film by Michael Keaton) and supervised by assistant managing editor Ben Bradlee Jr. He signals his intent by going to court to unseal depositions.

The 9/11 attacks intervene, but behind the scenes the Spotlight Team searches through records, pesters lawyers, and interviews victims, seeking to document the extent of the problem. In November a judge unseals a stack of critical depositions. By January Spotlight is ready to commence the public phase of its investigation, with a blockbuster story about Cardinal Law sending serial offender Geoghan to a new parish, despite having been warned against him by a trusted lieutenant. Tips flood in as the film ends.

That much is both newspaper and movie true.

The movie takes plenty of small liberties to retain its sharp focus and buttress the storyline of darkness and light. All seem to fall within standard Hollywood practice known as “based on a true story.” The statistics are a mess, because the stories discussed are describing events that took place over a span of40 years. The only real laugh-out-loud moment comes when the actress playing the crackerjack columnist McNamara whispers, “You mean there’s more than one?”

During 2002, the Spotlight treatment turned what had been a series of stories about a series of bad apples and their punishments into an overarching scandal of a church hierarchy mired in stubborn denial of its problems, unwilling to take the steps necessary to fix them. The Spotlight Team grew from four to ten persons, who together wrote some 600 stories. Cardinal Law resigned in disgrace in December. And the next April, the Spotlight Team won its third Pulitzer for The Globe -- this one its Gold Medal for Meritorious Public Service. By then, the story had begun to be replicated around the world.

Unfortunately, no book has been written about that epic contest of wills, though David France’s Our Fathers: The Secret Life of the Catholic Church in an Age of Scandal (Crown, 2004) employed the story as its spine. There are only the newspaper stories themselves, published as Betrayal: The Crisis in the Catholic Church (Little Brown, 2002); a Columbia Journalism School case study from 2009 that reads like a film treatment; and, of course, the screenplay itself, by Josh Singer and director Tom McCarthy. Baron, who retained his ties to Hollywood (earlier he had been business editor of the Los Angeles Times), apparently advised the filmmakers throughout. In 2013 he became executive editor of The Washington Post.

The film version departs from what a good newspaper story would tell back at that chasm. A new sheriff who takes in hand a troubled town is a plot familiar from many a classic Western. It doesn’t describe what happened in Boston.

Certainly there had been a time within memory when The Globe routinely downplayed news that the Boston Archdiocese found distressing. For much of its first century, the paper catered to readers in Boston’s rapidly expanding working class – preponderantly Irish, Catholic, Democratic, and, with every passing decade, more females. Editors clearly went out of their way not to offend. As recently as the early 1960s, sentences deemed inappropriate in coverage of the church were quietly excised by a senior editor thought to be in close touch with church headquarters.

After Thomas Winship took over as editor, in 1965, this began to change. The Globe had bested the respectable old Herald Traveler in a no-holds-barred newspaper war during the late 1950s and through the ’60s. Winship took advantage of his paper’s victory to rebuild The Globe into New England’s dominant newspaper, which made its mark with editorials like those that criticized the Vietnam War and vigorously supported court-ordered desegregation in Boston, if not always the busing that aimed to achieve it.

After William O. Taylor succeeded his father as publisher, in 1978, the paper continued to soar. The Globe credo was still spelled out in the words of its founder on a brass plaque in the lobby: “My aim has been to make The Globe a cheerful, attractive and useful newspaper that would enter the home as a kindly, helpful friend of the family….” (The saga is scrupulously told in a chapter of Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families, the classic account of Boston’s busing troubles in the 1970s, by J. Anthony Lukas.)

In 1993, the New York Times Co., corporate parent ofThe Times and a handful of much smaller papers, bought The Globe for $1.13 billion, the highest price ever paid for a newspaper up until then. For the next few years, The Globe continued to thrive under Boston management.

The NYT Co.’s makeover ofThe Globe began in 1998, when star columnist Mike Barnicle was humiliated and then forced to quit instead of scolded as he might have been in the past for any lapses. His defenestration was preceded by that of another columnist, Patricia Smith. People still argue about the merits of the cases, even as they forget the details. Both separations were inevitable in the circumstances.

In 1999, NYT Co. chief executive Arthur Sulzberger Jr. dismissed Globe publisher Benjamin Taylor and replaced him with a previously unknown executive from New York. Senior staffers Martin Nolan, David Nyhan, Gerard O’Neill, and Thomas Mulvoy took buy-out packages.

Then in summer 2001, Storin announced he, too, was leaving and New York hired Baron as the new editor. He made it clear that he intended to make over the Boston paper to a more stringent standard. The Taylor family credo had been discarded. “Make the news more relevant to readers,” as one newsroom catch-phrase had it at the time; “the joyless pursuit of excellence,” according to another. (I was one of those who leftThe Globe not long after Baron arrived.)

The other thing the movie leaves out is the backlash. There’s no easy way of telling what broad efforts by New York’s managers to re-shape The Globe cost the paper in terms of readership, especially since the decline in its revenues and circulation coincided with invention of search advertising and the rise of social media. But The Globe’s slide since 2002 appears to have been more precipitous than that of almost all other major papers, such that in 2009 New York threatened to simply close down the newspaper if labor concessions weren’t forthcoming.

Finally in 2013 NYT Co. soldThe Globe for $70 million, or around 6 percent of what it had paid20 years before, not to the Taylor-led group that had sought to buy it, but to another outsider, Boston Red Sox owner John Henry. Henry recently has become embroiled in misadventures of his own.

Thanks to the movie, The Globe’s brand has never shined brighter. And the paper itself, far slimmer than before, seems to have returned to its roots, under editor Brian McGrory. The business model, however, is badly damaged, perhaps even broken. The story of what happened to The Globe after it was sold awaits its Tony Lukas.

***

The Big Short is based on The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine, by Michael Lewis. Starting with Liar’s Poker: Rising through the Wreckage on Wall Street (Norton), in 1989, then with another ten books, Moneyball and The Blind Side among them, Lewis has demonstrated an astonishing knack for finding the right characters in order to tell important stories.

There are four main characters in the film – three idiosyncratic speculators, unknown to one another, each obsessed with betting against the housing market, and the bond trader who showed them how to play their hunch, using the new and less risky derivative instruments known as credit default swaps.

Actor Christian Bale plays real-life California neurosurgeon-turned-hedge-fund-manager Michael Burry; Steve Carell plays a Wall Street New York veteran who resembles real-life Steve Eisman in the book; and Brad Pitt is the worldly mentor to a pair of thirty-something friends who had worked briefly managing money on Wall Street before going into business for themselves in a backyard shed in Berkeley, Calif.

Ryan Gosling plays the Deutsche Bank bond trader – Greg Lippmann in real life – who taught them all the new way to make their trades. He is “Patient Zero,” in author Lewis’s pungent phrase. He is the narrator of the film. And since traders don’t do things by themselves, each of the four has associates, lawyers, therapists, family members – a highly interesting cast of characters who make the movie version remarkably true to real life in markets but who nevertheless get in the way of understanding.

The better way to place a wager against a market that Gosling peddles in the film is the strategy he describes in presentations that he makes to potential investors, “Shorting Home Equity Mezzanine Tranches.” Director and screenwriter Adam McKay ingeniously treats the strategy as a McGuffin – a device that sets the plot in motion without needing to be fully understood – though he makes two attempts to explain it as he goes along.

In the first instance, actress Margo Robbie describes the pooling and securitization of subprime mortgages – from a bubble bath (itself a sly joke, since Robbie appeared in considerably less in The Wolf of Wall Street, as Leonardo di Caprio’s mistress/second wife); in the second instance, in a Las Vegas casino, University of Chicago Booth School of Business Prof. Richard Thaler and singer Selena Gomez explain the nature of derivatives.

So much for the MacGuffin. What exactly is a credit default swap? It is an insurance contract, a derivative of a security, not the underlying asset itself. The esoteric new market was created in the 1990s and proved so useful to investors, for various reasons, that it grew exponentially. Gilliam Tett, of the Financial Times, tells the origin story in Fool’s Gold: How the Bold Dream of a Small Tribe at J.P. Morgan Was Corrupted by Wall Street Greed and Unleashed a Catastrophe, Free Press, 2009.

And the advantage such markets offered over traditional methods of shorting an asset? Author Lewis describes the basics this way in his book.

The beauty of the credit default swap, or CDS, was that it solves [a] timing problem. Eisman no longer needed to guess exactly when the subprime mortgage market would crash. It also allowed him to make the bet without laying down cash up front…. It was also an asymmetric bet, like laying down money on a number in roulette. The most you could lose were the chips that you put on the table; but if your number came up, you made 30, 40 , even 50 times your money.

There are two important things you don’t learn from the film version of The Big Short. One is that there was an investor, John Paulson, who actually made “a Soros trade,” a killing so great as to enter the ranks of legendary investors. The poignancy in the film derives from the fact that none of its heroes makes nearly as much money as he had hoped, because various backers run out of nerve.

Neurologist Burry makes $750 million for his investors in 2007, but the fund he is managing shrinks to $600 million, and threats of withdrawal continue throughout the coming year. Disillusioned, fearing for his health, Burry closes his firm in Cupertino a year later, despite gains of 489 percent over seven years.

Those thirty-something investors who started their fund in a backyard shed? By 2008, they are managing $135 million, up from $30 million, but can’t enjoy their subprime triumph because they are too worried about how to invest next. Eisman has sold his last CDS back to Lippmann in July 2008. He enters the autumn conventionally invested in the stock market, betting that the banks will fail.

Meanwhile, Paulson, a relatively well-known Wall Street investor previously deemed to have been a reliable hitter of singles and occasional doubles, succeeded brilliantly where Burry earlier had failed. In 2006 Paulson raised $137 million (including $30 million of his own money) with no other purpose than making bets with credit default swaps against subprime mortgages. He and his associates picked the right securities to short, and hit the jackpot: $15 billion for his hedge fund in 2007, including some $4 billion for himself. The story, with many of the same characters as The Big Short, is told in The Greatest Trade Ever: The Behind-the-Scenes Story of How John Paulson Defied Wall Street and Made Financial History (Broadway Books, 2009), by Gregory Zuckerman, of The Wall Street Journal.

The second thing you don’t learn from The Big Short is what actually happened after Lehman Brothers failed in September 2008, triggering a run on the banking system. The climax of the film comes in March 2008, as Bear Stearns is merged into J.P. Morgan, The scene at the end of the movie, with the Eisman character (Carell), sitting with his partners on the steps of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan on Sept. 18, 2008, as the whole world teeters on the brink, serves in the film, as in the book, to emphasize the immense harm that is about to ensue: the homes foreclosed, the jobs lost, the confidence shattered, the political divisions exacerbated.

The reason why has already been given: simple greed.

Never mind. The Big Short is a brilliant success, conveying the same truths about financial markets in 2007 that Michael Lewis adduced in the book – that finance is complicated, that money managers talk fast and crack jokes, that life is unfair. So it’s not the whole story. What is?

. ***

Movies are wonderful, but a problem arises when movie critics who know little about the background write as though the screenplay were newspaper truth.

Thus Nigel Andrews, in the Financial Times: “Tom McCarthy (The Station Agent) directs and co-writes as if the film were a hot-button documentary hijacked by stars, and in a way it is.”

A.O. Scott, in The New York Times: “Before 2001 – with some exceptions, notably in work by the columnist Eileen McNamara (played by Maureen Keiller) – the paper overlooked the extent of the criminality in the local church and the evidence that the hierarchy knew what was going on.”

Anthony Lane, in The New Yorker: “…Marty Baron, of all people, shy, taut, and humorless, in Schreiber’s clever portrayal – struck me as the hero of the hour. He is mocked for being, as one insider labels him, ‘an unmarried man of the Jewish faith who hates baseball,’ but it is precisely his status as an outsider that allows him to initiate the quest. Folks in the Church, and elsewhere in the city, know what went on, yet they don’t really want to know. It’s all too close to home. Baron wants to know.”

Ty Burr, in The Boston Globe: “’Spotlight’” makes the sharp, sobering point that it took an outsider, Baron, to notice what the locals didn’t, or couldn’t, or maybe even wouldn’t, and that The Globe had more than one chance to open an investigation years earlier than it did. The movie paints this as the regrettable bureaucratic oversight of a hectic workplace. It’s also true that people are flawed, and that institutions thrive by not making waves. Until something changes, and they do.”

And, perhaps most surprisingly, historian and journalist Garry Wills, of Northwestern University, in the New York Review of Books: “An instinctive deference to the Church had inhibited the press in this Roman Catholic city from recognizing a scandal in its own backyard. Baron was not subject to that thrall.”

As for the scene that serves as a climax, which occurs when, on the eve of the publication of the story that is to finally break the long silence, the team discusses the fact that in 1993, when Robby was metro editor, he had buried on page 43 the story of a lawyer’s claim that he had obtained settlements against 20 pedophile priests who had been retired or put on indefinite leave. It turns out it didn’t really happen like that. It was the screenwriters, not the reporters, who were tipped by lawyer Roderick MacLeish (played in the film by Billy Crudup) to the existence of that long-ago clip.

McCarthy and Singer found it and read it, then queried Robby about its significance. He promptly acknowledged he had been metro editor at the time – and they subsequently wrote a scene to buttress the story of the chasm between darkness and light. In the film Baron then pronounces benediction: When people have been in the dark for a long time, he says, they are necessarily disoriented; a light is turned on and suddenly things at last seem clear. All he knows, he says, is that the team has done a good job.

“That moment [the confession of knowledge and failure to act] was probably the one moment where we took something that was not [precisely true] and we felt that we had the right to include it,” director McCarthy told Jeff Labrecque of Entertainment Weekly for his story. “Spotlight players confront the clue that became the movie’s key twist.” The screenwriters already had “concluded from their research that the Globe was probably guilty of sins of omission, if not commission, when it came to its coverage of the Church in the early 1990s,” wrote Labrecque. Their discovery was a dramatic gift too good to pass up.

Maybe so, in the powerful logic of movie abstraction. But it’s far from newspaper truth. What really happened in that interval in 1993 was that The Globe changed editors and publishers, from Jack Driscoll and Bill Taylor to Matt Storin and Ben Taylor. The staff wrapped up the Porter and Hanlon stories, and prepared to take up the Geoghan saga when, two years later, attorney Mitchell Garabedian brought his blockbuster suit.

By the spring of 2001, a new judge, Constance M. Sweeney, had been chosen to take over the case. She was another outsider, a Springfield native, and a largely unsung hero of the story. In December she would, on The Globe’s motion, release 10,000 documents in the 84 lawsuits against Geoghan and Cardinal Law. The stage had been set for the Spotlight series – the single most important story in the 142-year-history of The Boston Globe.

David Warsh, a longtime financial journalist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

Raja Kamal/Arnold Podgorsky: Reform Judaism's lessons for Muslim immigrants

In a recent article in the Eurasia Review, Riad Kahwaji identified a troubling relationship between ISIS-inspired terrorist attacks and increasingly hostile reactions from nationalist and other right-wing parties across Europe. Muslim immigrants most often arrive in the West from Islamic countries beset by oppression, illiteracy and poverty, he notes. Western Muslim leaders have not effectively addressed these challenges, and resistance to assimilation by many in their communities has made them more vulnerable to extremism.

Among the factors that make integration into Western societies difficult for Muslim immigrants are the ways in which Islamic principles have been inculcated by parents and other elders; apparent biases concerning life in the West that have been influenced by government, political and religious propaganda in their countries of origin; and a lack of cultural empathy, common languages, and understanding of Western culture. In addition, Muslim communities in Europe are overly reliant upon imams recruited from abroad who are not overseen by an Islamic higher authority that sets standards of education and practice for the clerics.

Combine these factors with resistance from elements of the predominantly non-Muslim population, high unemployment rates among young Muslims and lack of opportunity for social and economic advancement, and it is easy to see why a significant minority of Muslim youths in Europe and certain U.S. communities are susceptible to radicalization. In France, about 10 percent of the population is Muslim, but 70 percent of the prison population is – and prison is the single most fertile ground for recruitment of terrorists. Attacks by individuals and groups purporting to represent Islam not only alienate average citizens but also produce a furious backlash of anti-immigrant fervor on the part of right-wing political leaders and organizations.

To address the challenges faced by Muslim immigrants, it might be instructive to consider the lessons of the Judaic diaspora. After their destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, in 70 A.D., the Romans expelled the Jewish people from the Holy Land. For centuries, Jews often lived separately from indigenous populations, gathering in tightly knit communities. Informed by suspicion of “the other” and often by outright antisemitism, what today would be called “host communities” frequently prohibited Jews from participating in most professions and crafts and in the political and cultural life of the societies. Sometimes, anti-Jewish attitudes were expressed violently, and attacks on Jewish people and their communities were not uncommon. Jewish separateness, whether voluntary or enforced, was essentially the norm.

By the end of the 18th Century Reform Judaism emerged in Germany and eventually in the U.S. The movement developed in part as an extension of the growth of rationalism in Western thought since the Enlightenment and in part as a reaction to the strictures and separateness that traditional Judaism demanded. The Reform movement (and, to a lesser extent, the movement for Conservative Judaism) advocated a relaxation of the more fundamental practices of traditional Judaism and greater assimilation into the economic, educational, and political mainstream of European societies. It welcomed modernity. In place of strict observance, Reform Judaism emphasized ethics, charity, and the admonition to “heal the world” as essentials of the Jewish character.

To bolster new ideals, an infrastructure of Jewish institutions and organizations evolved that not only served the needs of Jews but also interacted with similar structures in host societies. Among the new institutions that were most critical were seminaries that provided rigorous professional education for new generations of rabbis.

Over time, the threats of political oppression and violent antisemitism diminished in many places (not at all times or in all places, but generally). Progress was made in part because it was based on the long-established Judaic principle that Jews are to respect the laws of the lands they inhabit (except where they directly conflict with fundamental Jewish belief as, for instance, in the case of idol worship).

The Reform movement spawned contemporary Jewish pluralism, which now includes several streams of Jewish thought and practice. These diverse approaches provide an example of integration and response to evolving philosophical and political norms, while preserving essential and nourishing tenets of the Jewish faith. Adherents have managed to assimilate effectively into societies that are predominantly non-Jewish by adapting religious practice and expression to fit with the laws, culture and customs of their adoptive homelands.

Might the experience of the Jews in Western societies provide a model for the growing Muslim communities of Europe and North America? Perhaps so, but it is essential that reform in Islamic practice and custom be initiated and molded by leaders in those Muslim communities. We recognize that such efforts to reform will be met with resistance, but success is possible if all remember that, in our diverse communities, we can only embrace the ways of peace by respecting and making room for each other – and, in matters of faith, there is always more than one path up the mountain.

Raja Kamal is senior vice president of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging; based in Novato, Calif. Arnold Podgorsky is a lawyer and former president of Adas Israel Congregation in Washington, DC, a Conservative synagogue.

More training for New Englanders

“Early spring plants are pretty tolerant of cold temperatures,” Killingbeck said, “but it depends on how cold it gets and how long those cold temperatures last. It’s in the realm of possibility that flowers could pop open, bloom and get zapped by a long, cold frost and be toast for the season. A lot of trees are susceptible, too. That’s a lot of energy the plants and trees expend for nothing.”

Our friends at the New England Board of Higher Education ran this note on their Web site (nebhe.org):

New England's railroads are an overlooked asset in the region's education and economic future. MassLive reports that planning is in the early stages for frequent north-south passenger trains on the "Knowledge Corridor" from Springfield, Mass., stopping in Holyoke, Northampton and Greenfield. Recently, freight trains began carrying the first shipping containers loaded on the Portland, Maine waterfront to connect with freight customers throughout North America. It’s cheaper to move heavy cargo by train than truck, because more can be moved at once with less fuel and fewer workers. In the Boston area, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority is revisiting an idea first proposed in 2014 to sell large quantities of discounted passes to colleges and universities. Railroads already offers convenient passenger service to Bridgewater State University and the University of New Hampshire, as well as Greater Boston campuses.

Smiling through the slush

"Spring is when you feel like whistling even with a shoe full of slush."

"Spring is when you feel like whistling even with a shoe full of slush."

-- Doug Larson

Chris Powell: Irresponsibility about retirement and voting

Government, Lincoln said, should do for the people what they need to have done but cannot do at all or so well for themselves as individuals. While Connecticut has not been following Lincoln's standard for a long time, if his standard ever was followed state government would reject the proposal to establish a retirement savings program for private-sector workers.

Of course people don't save enough for retirement, and government probably would suffer less expense for care of the aged if they saved more. But the proposed retirement savings program has little to recommend it.

First, such a program would accomplish nothing that people can't already do for themselves. The program would do no more than establish individual retirement accounts for people and require employers to facilitate regular payroll deductions to fund the accounts. But many employers already offer retirement savings plans with regular payroll deductions, and it is no problem that many employers don't, since hundreds of investment houses will establish them for individuals and fund them through automatic deductions from an individual's checking account.

Either way the results for the retirement saver are the same.

Second, advocates of a state program acknowledge that it probably would not cover its management costs until it had amassed a billion dollars in retirement savings contributions. That probably would take a few years and maybe much longer. In the meantime a substantial new state government agency would have to be created to run the retirement saving system at tax expense.

Of course the agency's employees would not have to participate in the retirement savings plan supervised by their agency. As state government employees they would qualify for state government's excellent defined-benefit retirement savings plan and retiree medical insurance, benefits guaranteed by state government, while the pension agency itself was providing private-sector workers only an ordinary defined-contribution retirement savings plan -- that is, a plan with benefits subject to stock market risk and no medical insurance.

The only good reason to establish such a retirement savings system would be to facilitate the gradual transition of state government’s defined-benefit pension system into a defined-contribution system for new employees.

xxx

Connecticut Secretary of the State DeniseMerrill has what ordinarily might be a good idea -- to register people as voters whenever they undertake a transaction at offices of the state Motor VehiclesDepartment, unless, of course, they are already registered or don't want to register. Merrill estimates that as many as a third of Connecticut's eligible adults are not registered to vote though most have driver's licenses.

The problem is that amid the turmoil at the Motor Vehicles Department arising from the botched recent implementation of its new computer system, the department lately hasn't been competent to do even its ordinary work. If the department started registering voters now, many might end up registered in the wrong towns. So Merrill's proposal should be set aside for a few years.

In any case the problem with all those unregistered adults is not the current voter registration system, in which registration already is easy. People can register during business hours at town halls, at the many registration outreach events held by voter registrars, and on the Internet.

Even so, not only do maybe a third of the state's eligible adults fail to register, but in a typical election half of the people who are registered don't bother to vote. Indeed, participation in Connecticut's elections was far higher years ago when voter registration was not as easy as it is now.

So Secretary Merrill is not addressing the real problem -- the failure of parents and public education to engender civic virtue amid the corruption of prosperity, which is the historic bane of civilization.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

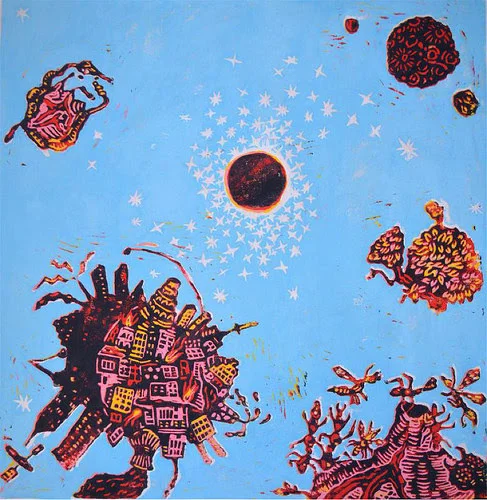

"Blackhole'' (print), by Vinicius Sanchez

"Blackhole'' (print), by Vinicius Sanchez, in the show "Push/Pull: Recent Work from the Printmaking Faculty,'' at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education, through March 11.

Nitrogen runoff versus herring runs

A herring run in part of Westport, Mass., renews questions about nitrogen pollution's destructive effect on wetlands.

Some observers believe that elevated nitrogen levels from lawns, farms and and golf courses discourage marsh grasses from putting down the deep roots that knit marshes together since the runoff makes nitrogen excessively plentiful at surface levels. And they worry that the nitrogen fuels the thick green algae that can clog herring runs during warm weather and kill much life by sucking up too much of the oxygen.

Playground

"Study for Bed 1'' (oil on canvas), by Jacob Collins, in his show "Jacob Collins: Landscapes and Still Lifes,'' at Adelson Galleries, Boston, opening March 4.

Yankee architectural economy

"Consumable Sugarhouse,'' in Norwich, Vt.

“A sap run is the sweet good-bye of winter”

So wrote American naturalist John Burroughs in 1886 about the weeks in March and early April when warm sunny days and still-freezing nights draw the sap through the veins of sugar maples ripe for tapping.

For Keith Moskow FAIA and Robert Linn AIA, both of Moskow Linn Architects, Boston, this year’s sugaring season will also be a sweet reminder of summer, when Studio North, their weeklong intensive-training program for architecture students who want to learn building basics as well as design skills, created a sugarhouse with “consumable” walls. The structure, built with standard framing material, is a pavilion, open on three sides, with a metal shed roof.

It is sited on a gentle wooded slope with a pond view near Norwich, Vt. The maples are uphill, so gravity carries the sap from the trees through tubes to a storage tank at the solid back wall of the 11-by-14-foot house. It takes a lot of wood to fuel the evaporator inside the shed that will boil down the sap, which is 98 percent water, turning it into syrup.

The design solution is to pack the open walls with firewood. In winter, the shed serves as a way station for cross-country skiers. In sugaring season, logs are taken from the top down, and by the end of the sugaring season only the frame and roof remain. Syrup made, wood consumed, the walls of the pavilion open to the forest, and the structure becomes a rustic teahouse ready for a long meditative summer.

This was sent by:

Moskow Linn Architects – Studio North

88 Broad Street

Boston, MA 02110

617 292 2000

'Land of abstraction'

.

"Shippwrekked (BR15-108'') (acrylic on fabric), by Brent Ridge, in show "Liz Gargas and Brent Ridge,'' at the New Art Center, Newton, Mass., March 4-April 10. The gallery says that Mr. Ridge "operates in a land of abstraction rooted in appropriation, landscape, and post-industrial aesthetics''

Anastasia Walker: Public hoopla over private parts

via OtherWords.org

As the recent attention lavished on figures like Laverne Cox and Caitlyn Jenner attests, trans visibility continues to rise in the United States. But that doesn’t mean life is suddenly easy for us transwomen.

Take something as simple as obeying nature’s call. Trips to public restrooms can be terribly stressful for us — even for folks like me who ”pass” as cisgender.

It took me over a year after I first embraced being trans to screw up the courage to enter a women’s room. Even now, two years after I first started presenting as female 24/7, I find myself furtively scanning the faces of the other women when I’m standing in a long bathroom queue.

Why? To confirm that no blowup is brewing.

Being identified as trans by an unfriendly stranger can lead directly to verbal or physical harassment — or even assault. So when we’re out in public, we often avoid behavior that might attract attention. Like making eye contact. Or showing our hands. Or speaking.

Unfortunately, conservative legislators across the country are making this experience more stressful than it already is.

Over the past year, laws have been proposed in several states that would ban transgender citizens from using bathrooms appropriate to their gender identity. These bills call for fines and even jail time for anyone who refuses to comply.

South Dakota, where lawmakers have passed a bathroom bill targeting transgender schoolchildren, may become the first state to enact one.

Republican Gov. Dennis Daugaard, in whose hands the decision now lies, initially claimed he’d never even met a trans person — and didn’t intend to before deciding whether to sign it. (He was forced to reverse that position, thankfully, and met with some trans students on February 23.)

Why is the far right making so much public hoopla over our private parts? They say it’s to preserve ”privacy rights.” Behind that highfalutin rationale, though, is the specter of (cisgender) women and girls being attacked by male sexual predators “disguised” as female.

To transgender Americans, these “bathroom bills” represent one of the more frustrating — and mystifying — forms of backlash against our emergence into the national spotlight.

Frustrating because the fear-mongering these bills foster is obstructing passage of sorely needed reforms, like protecting trans kids from bullying at school.

Mystifying because, as groups like the American Civil Liberties Union, Media Matters, the Human Rights Campaign, and the Transgender Law Center have shown, there’s no credible evidence whatsoever that “the predatory transwoman” exists anywhere outside of right-wing fantasies.

So why all this clamoring to restrict our bathroom access?

The truth is, the right isn’t concerned about our actions (real or imagined). Indeed, as the South Dakota governor’s bizarre initial refusal to meet one of us attests, who we are as people is beside the point.

The menace we pose is instead symbolic: Our very existence threatens their vision of a strictly gendered social order — one rooted in the nuclear family, with Adam and Eve serving as the prototype. To accept gender variance is to question the fundamental distinction between “man” and “woman” that this vision depends on.

But instead of arguing that their vision trumps a more inclusive one that embraces us, they’re demonizing us. Instead of recognizing us as a vulnerable group whose rights need to be protected, they’re trying to make us illegal.

Sadly, this scapegoating resonates with many people. The pivotal role a vicious anti-trans ad campaign played in toppling Houston’s high-profile LGBT rights ordinance last November bears this out all too well.

On the upside, times are changing: Demonizing us is no longer enough to keep us in the closet. The fact that they’re resorting to crass fear-mongering over who pees where suggests how desperate they’re getting.

Education and increased visibility are slowly shifting public opinion in our favor. In the meantime, lawmakers should focus on the many real challenges facing the nation right now — and let us pee in peace.

Anastasia Walker is an essayist, poet and scholar who lives and works in western Pennsylvania.

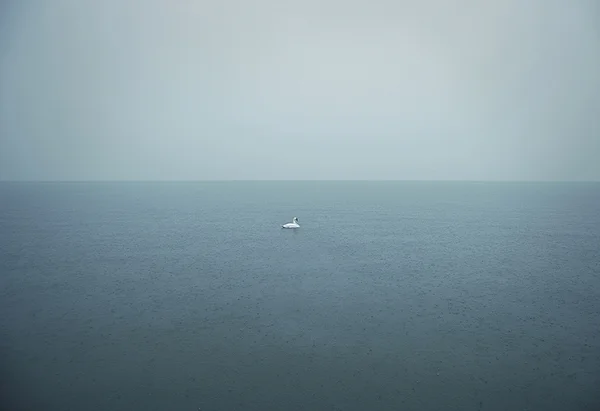

Might be washed away in 100 years

"South Beach,'' by Bobby Baker. (copyright Bobby Baker FIne Art Photography.)

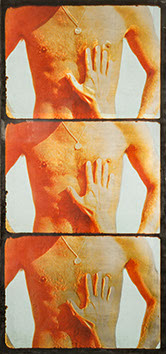

This is not a proper introduction

"BITS Bayside 5'' (archival inkjet, silkscreen, palladium leaf on paper), by Gabriel Martinez at Samson Gallery, Boston.

David Warsh: Trying to make sense of America's age of disaggregation

"I am as eager as the next guy to make sense of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, but I do not expect to work my way through to useful opinions by following the primary and caucus returns."

Seeking distance from the dispiriting political news, I spent the best hours of last week reading various chapters of four books by Princeton historian Daniel T. Rodgers. I am as eager as the next guy to make sense of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, but I do not expect to work my way through to useful opinions by following the primary and caucus returns. So I turned to the work of a scholar who has spent his career writing about the evolution of the political culture of modern capitalism in the U.S. over the last 150 years.

I first read Rodgers a few years ago after an old friend recommended Age of Fracture, which had won a Bancroft Prize in 2012. I was struck by how attentive the historian had been to various developments in economics in the 1960s and ’70s I knew something about: the influence of deregulators such as Ronald Coase and Alfred Kahn, macroeconomists Milton Friedman and Robert Lucas, lowbrow supply-siders, highbrow game theorists, legal educator Henry Manne.

I know much less about the other realms Rodgers reconnoitered in the book in order to elaborate his central metaphor – international relations, class, race, gender, community, narrative. But I know that his fundamental diagnosis rings true. Life today is more specialized, more highly differentiated, and, yes, somehow thinner than in the past.

"Conceptions of human nature that in the post-World War II era had been thick with context, social circumstance, institutions and history gave way to conceptions of human nature that stressed choice, agency, performance and desire. Strong metaphors of society were supplanted by weaker ones… Imagined collectivities shrank; notions of structure and power thinned out. Viewed by its acts of mind the last quarter of the century, was an era of disaggregation, a great age of fracture.''

Over the next year I skimmed Rodgers’s three previous books. They turned out to offer a fairly seamless narrative of, not so much economic history, but arguments about economic history, over the course of a century and half. Rodgers was born in 1942, graduated from Brown University in 1965 and got his Ph.D. from Yale in 1973, taught at the University of Wisconsin until 1980, when he moved to Princeton University, where today he is the Henry Charles Lea Professor of History, emeritus

That first book, The Work Ethic in Industrial America: 1850-1920, traced American attitudes towards work, leisure and success, from relatively small-scale workshops before the Civil War to highly mechanized factories at the beginning of the industrial age. The second, Contested Truths: Keywords in American Politics since Independence, identified a handful of ostensibly technical terms – “utility,” “natural rights,” “the people,” “government,” “the state,” and “interests” – and examined their use in arguments, especially as the confident tradition he describes as “liberal” gave way to a rediscovery, both academic and popular, of “republicanism” in the Reagan years.

The third work, Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age, is a highly original reconstruction of various ways “progressivism” was understood in the first half of the twentieth century, in Europe and the United States: corporate rationalization, city planning, public housing, worker safety, social insurance, municipal utilities, cooperative farming, wartime solidarity, and emergency improvisation in the Great Depression. (A research assistant was Joshua Micah Marshall, who went on to found the influential online news site Talking Points Memo.)

Age of Fracture is the fourth.

It’s a rich vein. I plan to mine all four over the next few months, making a Sunday item, when and if I can. One needs something to discipline mood swings during the rest of the campaign, and I’ve decided that, for me, this is it.

Today I’ll offer a small but concrete example of what Rodgers calls “ideas in motion across an age,” or, in this case, many ages. American exceptionalism is a persistent theme with him: the free-floating idea that, as “the first new nation” and “the last best hope of democracy,” the United States has a mission to transform the world and little to learn from the rest of it. Is that the note that Trump so single-mindedly and simple-mindedly strikes when he promises to “make American great again”? It helps me to think so.

As for Rodgers, he is spending the year in California, writing a fifth book, a “biography” of a 1630 text that would come in time to be seen as central to the nation’s self-conception — the John Winthrop sermon that contains the famous phrase, “[W]e shall be as a city on a hill.”

David Warsh, a veteran economic historian and financial journalist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this originated.

The most serious charge...

"The most serious charge which can be brought against New England is not Puritanism but February."

- Joseph Wood Krutch

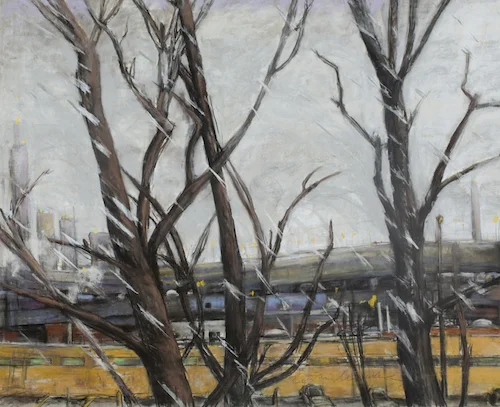

Post-industrial grid

'

"Landscape'' (drawing), by David Campbell, in a show at the Brickbottom Gallery, Somerville, Mass., through Feb. 27.