Schoolhouses are our fortifications

Statue of Horace Mann outside the Massachusetts State House. In 1852, the state enacted the nation’s first mandatory public school attendance law, in large part because of Mann’s campaigning for it

“Education is our only political safety. Outside of this ark all is deluge.”

“Forts, arsenals, garrisons, armies, navies, are means of security and defense, which were invented in half-civilized times and in feudal or despotic countries; but schoolhouses are the republican line of fortifications, and if they are dismantled and dilapidated, ignorance and vice will pour in their legions through every breach.”

— Horace Mann (1796-1859), American education reformer, slavery abolitionist and Whig politician best known for his commitment to promoting public education. He was born in Franklin, Mass.

From the time he was 10 to when he reached 20, he had no more than six weeks' schooling during any year, but he made copious use of the Franklin Public Library, founded in 1790 as the first public lending library in America. At the age of 20, he enrolled at Brown University and graduated in three years as valedictorian. Franklin was named after Benjamin Franklin (1707-1790), who gave the town 116 books, which of course ended up in its its library.

The current Franklin Public Library, opened in 1904.

— Photo by Swampyank

Notating the landscape

“Winter Rill” (acrylic on canvas), by Anni Lorenzini, in her show “In Sight: Notating the Landscape,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Feb. 3-26. She lives part of the year Waterford, Vt.

She writes:

"'All I could see from where I stood...' Here poet Edna St. Vincent Millay pinpoints the artists' charge; to paint what you see as you see it.

“I notate the landscape with random strokes, smears and smudges. These tangled dots develop into intricate patterns that form the earth and sky. I respond to the intimate structure of each landscape painting as I learn to paint with my chosen tools.

“I apply paint with everyday household tools like sponges, rags and squeegees. These tools come from my life, providing an authentic means for artistic expression as I live on this fragile and beautiful earth."

Waterford, Vt., seen across Moore Reservoir

— Photo by P199

R.I. bumblebee survey helps track species decline

Bumblebee in flight. It has its tongue extended and a laden pollen basket.

Photo by Pahazzard

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The brilliant blue morning sky was made more vibrant by the contrasting field of goldenrod in the Great Swamp Management Area, in southern Rhode Island, where Katie Burns stood. Alone in the cacophony of insect song, she quietly let her eyes adjust to the unique movements of the different pollinators around her before spotting a particular flight pattern. She swept her net through a swath of goldenrod, catching a bumblebee, and crooned to the insect as if it were a puppy as she coaxed it into a specimen jar and pointed out its identifying characteristics.

“One of the ways I can tell this one is a male is because he has a little mustache,” she said. “See?” And he did, indeed, have a little mustache that matched the earthy yellow of his stripes. She opened the jar and he flew off to return to his breakfast, seemingly unaffected by his brief capture.

“That bumblebee was an unwitting volunteer for the Rhode Island Bumblebee Survey (RIBS), a Rhode Island Pollinator Atlas project led and developed by Burns. The Atlas, backed by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), Burns’ employer, will provide entomologists with baseline data. It will inventory the bee, butterfly and hoverfly species that currently live in Rhode Island, assess what resources are important to them, and pinpoint their preferred habitats so that scientists can track population declines and protect pollinators’ chosen dwellings.

There are an estimated 250 species of bees in Rhode Island, and Burns is starting her project focusing on one genus in the bee family: the bumblebee.

“Historically, there were 11 species of bumblebee in Rhode Island,” Burns said. “But currently, we can only find six.”

A combination of factors affected the other five. Some of the southernmost populations vanished as climate change made Rhode Island less habitable. Others struggle because of a lack of food sources.

“Bees we see disappearing are closely co-evolved with a flower species,” Burns said. “Their relationship is like that of puzzle pieces. And because they have such a specific niche, loss of resources can really affect them.”

She’s curious to see if this research will find the missing species in tiny pockets of the state. “Maybe they’ve found their niche on Block Island,” she said. “But we have to know who’s out there before we can help them.”

To gather data for the survey, Burns is relying on a group of volunteer community scientists — members of the public who are not necessarily professional scientists, but gather data for scientific studies. Each volunteer is responsible for a 1-hectare region in one of the 5-kilometer-by-5-kilometer squares making up an imaginary grid that overlays the state.

“It’s the same grid that the Rhode Island Breeding Bird Atlas used for their data collection,” Burns said, emphasizing her imitation was more than just flattery. “Using their grid is a move toward interspecies stewardship. If you have a healthy pollinator population, you’ll get more plant material, more seeds, more fruit, more food for birds. It’ll be interesting to see the food webs when these grids overlap.”

Volunteers are tasked with conducting a 45-minute survey in their chosen hectare once a month. “It’s 45 minutes divided by the number of people surveying the hectare,” Burns clarified. “So do it with a friend.” She also advises volunteers to choose a spot they already feel a kinship to — a place where they like to walk their dog or hike.

“Being part of a project like this helps people solidify their sense of place. When we know our neighbors, our community is stronger. But communities are made up of more than people,” Burns said. “They’re made up of plants and foxes and bunnies and bees. By learning how to identify some of the species in your backyard, it helps you feel connected.”

Volunteers begin each session with a habitat assessment before starting a timer and catching every bee they see. Those bees go into a cooler where they sleep through an unexpected artificial winter until volunteers can take photos of them. Then the bees warm up and fly off.

One of the 5 kilometer by 5 kilometer grids lands on Providence College, and biology Prof. Rachael Bonoan and a group of her students claimed it.

“During the school year, when I’m bogged down in teaching, it’s nice to have an excuse to go outside once a month,” Bonoan said. “But the biggest benefit was that this was an opportunity for me to teach my students survey methods and bumblebee identification while contributing to a larger body of research.”

Bonoan and her students were part of Burns’s pilot program, which ended in October. The program had 14 active volunteers, and Burns said she learned a lot through the experience. “My lovely volunteers, bless them, have been very patient with me,” she said with a laugh.

“The biggest thing I learned is how important on-the-ground training is,” Burns said. “I’ve been doing this work for 10 years, so it’s easy for me to say, ‘Go catch bees!’ But the response is, ‘You want me to catch something that can sting me and put it in a vial?’”

Community scientists have little to fear, however. Neither Bonoan nor Burns had experience with the business end of a bumblebee during their research.

Burns interrupted her description of the volunteer program to talk to an insect and burst a couple of jewelweed pods, in a charming display of her love for nature. “You don’t have to be an expert to enjoy nature,” she said. “I just want to encourage curiosity in people.”

Burns believes that it’s a mistake to rely solely on institutions and agencies to protect the environment. “We’re not being set up for success,” she said. “That’s why I like doing public engagement. And I try to make learning experiences as joyful and accessible as possible.”

A self-professed “theater nerd” in school, she brings many of the skills she learned on the stage to her work. “I’ve done comedy routines, podcasts, Soapbox Science — where a group of women scientists would go into public places, stand on soapboxes and just start talking — and PechaKucha,” she said.

At a late summer PechaKucha Night, a speaking event that highlights community members’ contributions to the state, Burns shared the stage with local artist, educator, and children’s entertainer Ricky Katowicz. “I was so impressed with her style of presenting,” Katowicz said. “She showed a lot of love for what she does.“ The pair teamed up to do a bug-themed show, appropriately called “Bugs,” in October.

“Katie has a very commanding presence,” Katowicz said. “When she talks, people listen.”

Burns has to make people listen because the things she says about the path we are on are important.

“The most immediate repercussion of pollinator decline is a loss of plant diversity, which may not be the end immediately,” she warned. “But if we have fewer plants for pollinators and fewer pollinator species, if a disease takes out a big species, like honeybees, we’d have a problem. Would there be anything left to pollinate crops?”

In the fruit orchards of southwest China, heavy use of pesticides has decimated local pollinator populations. Some farmers have to hand-pollinate their fruit trees, using paintbrushes and little pots of pollen. “It sounds like ‘Black Mirror’ stuff,” she said. “But it’s real and here and happening now. It’s a glimpse of what the future could be without our pollinators.”

Burns has some advice for those who want to help steer us onto a new path. Mow less. Reduce pesticide use. Plant native food species. Plant native wildflowers. Turn off outdoor lights at night so moths and beetles don’t get disoriented.

“Embrace a messier lifestyle,” said Burns, describing the winter yards most attractive to pollinators. “If you’re really brave, leave all your fall leaves where they landed. Hollow plant stems and leaf litter provide a perfect winter habitat for dormant pollinators.”

It’s an incredible exercise of imagination to look at a dead winter field and picture how much life exists there — the butterfly larvae hiding in the skeletons of summer plants and tiny creatures tucked under a blanket of leaves.

“These miniature worlds that surround us so often go unnoticed, but once you see them you can’t look away,” Burns said. “These thriving communities are just as fascinating as our own. And what a privilege it is to recognize and be part of that world.”

Burns is seeking to recruit between 60 and 70 volunteer community scientists to help her collect data for The Rhode Island Bumblebee Survey in 2023. The data collection season will run from April to October. For information on volunteering, go to https://forms.office.com/g/6XUxyP3rGc.

Of two minds

“To Center,’’ by Newton, Mass.-based Delanie Wise, in the group show “Stirring + Layering,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, Feb. 1-26.

The gallery says:

The fractured figurative work of Delanie Wise delves into our individual and collective experiences, as well as the congruity of opposing forces. Wise’s ceramic sculptures, while not definitively self-portraits, reflect her own sensibilities yet posit her life experiences are more universal than unique. A bust depicts a woman literally of two minds—her head neatly bisected, while another figure is part woman, part vase, trapped in her vessel. Or is she a magical genie emerging?’’

The Newton Public Library. The city is nationally known for its fine public schools and the generally high level of literacy, general knowledge and civic engagement of its residents.,

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

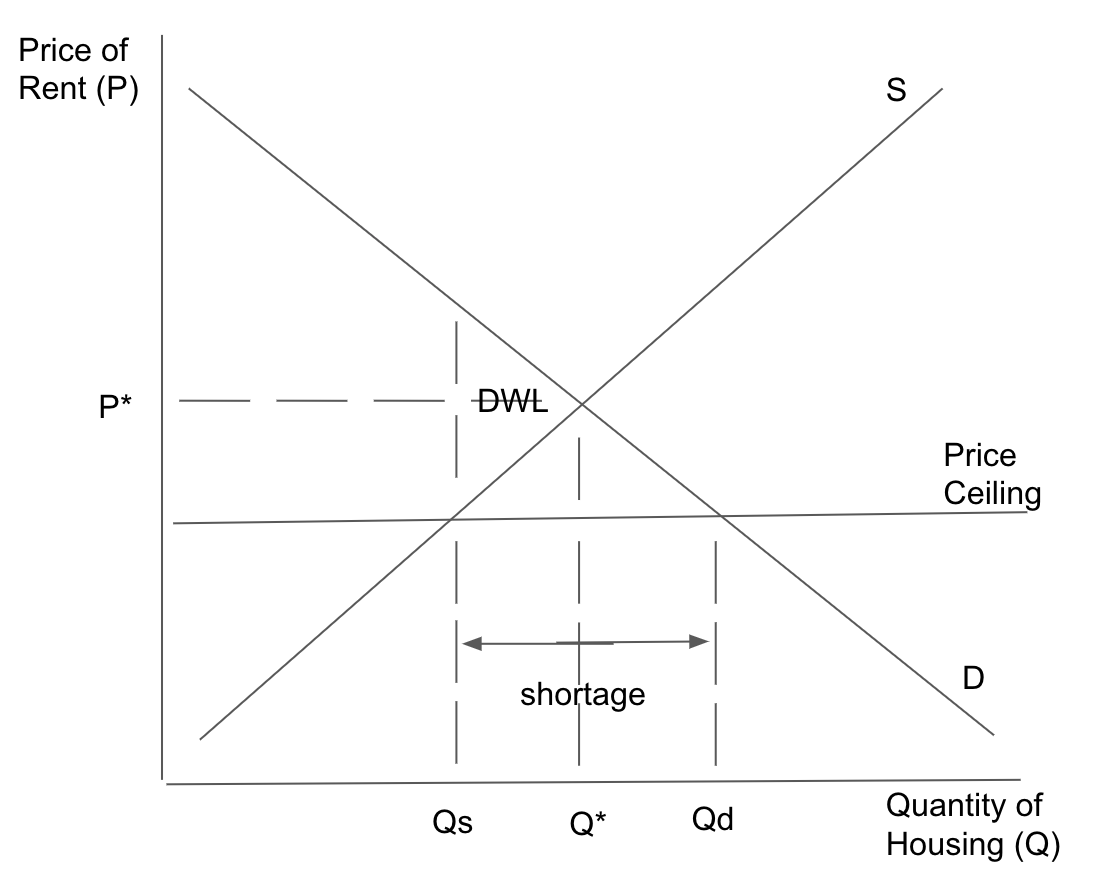

Chris Powell: Rent control worsens housing shortage; teacher union greed

A price ceiling will create a shortage in between Qs and Qd.

— Photo by Karinnna13

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut may have had its "All power to the Soviets!" moment the other day as more than 200 people summoned by the Democratic Socialists of America gathered on the Internet to call for a law to limit residential rent increases to 2½ percent annually. Five Democratic state legislators have co-sponsored the legislation and thus have tainted themselves with its demagogic scapegoating, its accusation that landlords are uniquely responsible for inflation.

"Our rent increases every year and our incomes do not," a tenants union activist said -- an excellent point immediately discredited by the failure to acknowledge the wider world.

That is, real wages throughout the country long have been falling behind inflation in all important respects -- not just the cost of housing but also food, electricity, gasoline, medicine, education and other essentials.

So where is the legislation to limit those costs?

Such legislation can't be introduced without exposing the scapegoating being done to the landlords, nor without revealing that a substantial percentage of inflation is caused by government itself as its creation of money far outstrips the production of goods and services.

While Connecticut has a severe shortage of inexpensive rental housing, the rent-control legislation has just struck a powerful blow against efforts to get more such housing built or renovated.

For what housing developer or landlord will want to risk his money building or renovating apartments when state government may prohibit him alone from fully protecting himself against inflation?

Under the rent-control legislation, everyone else in commerce will remain free to raise prices by any amount to cover himself against inflation, and apartment tenants will be free to demand higher wages in any amount. But the rental-housing business will be strictly limited to price increases far below the inflation rate.

The result of this will be still more scarcity inflating housing prices. Under rent control housing providers will be effectively expropriated by inflation.

That's "democratic socialism" for you -- diverting the blame from government without ever solving the problem government itself caused. Whom will the "democratic socialists" scapegoat next?

xxx

Guess how Connecticut's teacher unions want the state budget surplus distributed.

It's not to do anything compelling. No, the teacher unions want to use the surplus to increase their members' pay, which is already nearly the highest in the country.

Connecticut does have a problem with teachers, as it does with police officers. As social disintegration worsens, especially in the cities, fewer people want to teach where as many as half the students are chronically absent and many misbehave, and fewer people want to work in law enforcement where respect for law has collapsed.

As a result many teachers and police officers in the cities have been leaving for jobs in the suburbs, where social disintegration isn't as bad and they are paid more for easier work.

But that is no reason to increase compensation for teachers generally. It is a reason to increase salaries for teachers where more teachers are most needed particularly -- and not just in the cities but in particular subjects.

Typically, teacher union contracts won't allow that. So any new state money addressing the teacher shortage should be exempt from union contract restrictions.

Any new money also should come with audit requirements to determine if the money improves student performance, which is so bad in the cities that no additional spending is likely to accomplish anything unless it hires parents for the kids.

xxx

The Board of Education in Bridgeport, whose schools long have been in turmoil and whose students perform terribly, wants to hire a public-relations company. According to the Connecticut Post, the company would "manage the district's reputation, provide risk mitigation and consultation services, develop a crisis response plan, and train administrators in crisis communications."

It's as if the board has never heard that to change the image, it's necessary to change the reality. But then all Connecticut seems to have given up on changing the cruel reality of its cities.

Chris Powell (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com) is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

And where is the classic winter?

“New England Light” (acrylic on panel), by Linda Hefner, in the Duxbury (Mass.) Art Association’s “Annual Winter Juried Show,’’ through March 28.

She writes:

“Classic New England architecture is a dying breed. My work celebrates the endangered beauty of old New England barns, schoolhouses, and grange halls, and by extension, the rural communities that depended upon them for daily survival. I build my paintings up slowly and meticulously, focusing on accuracy and fine detail as well as on the play between light and shadow. These wonderful handmade buildings have so much beauty and strength, and I want to invite viewers to share in that with me and to appreciate these monuments of a vanished time before they’re gone.’’

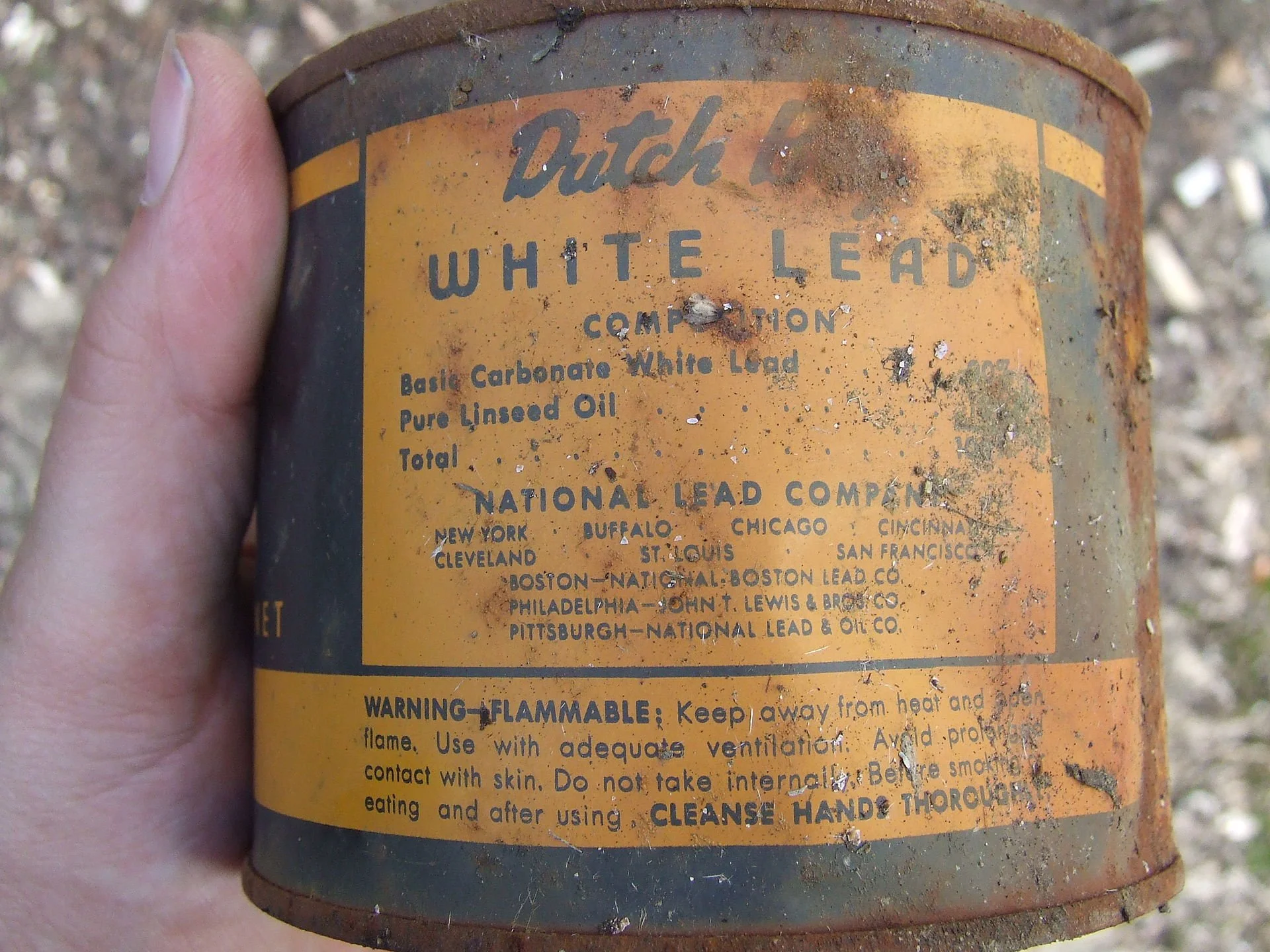

A leaden state

Cracking peeling lead paint.

“New Hampshire has one of the oldest housing stocks in the nation, which puts us all at a heightened risk of lead poisoning” {from lead paint}.

— Chris Sununu (born 1974), New Hampshire’s current governor

—Photo by Thester11

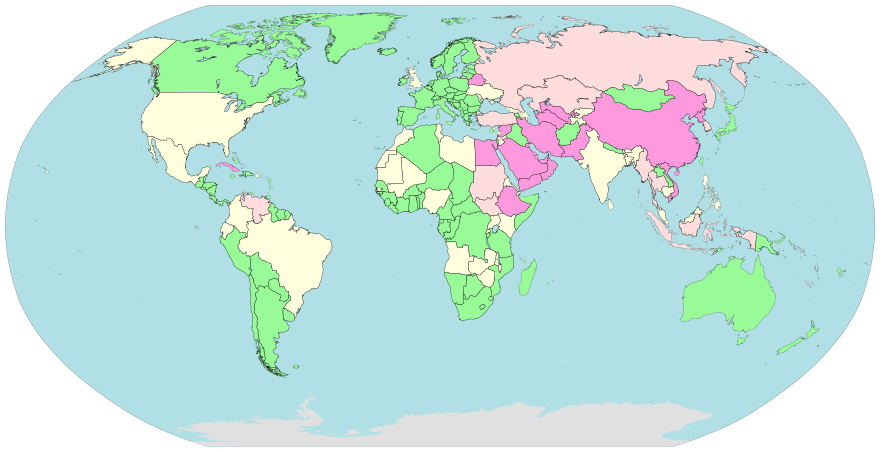

Is it worth it?

—Map by Kelisi

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“Yet each man kills the thing he loves….”

-- Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), Anglo-Irish playwright and poet

Poor old Cape Cod, once rural and now exurban and suburban.

There’s not enough money at the moment to replace the old (from the 1930s) and too narrow Sagamore and Bourne bridges. And pollution from septic systems, fertilizers and pesticides (lawns and golf courses are major sources) kills life in many freshwater ponds. There are 42 golf courses on the skinny glorified sand bar we call Cape Cod!

What to do? Year-round passenger-train service to reduce car traffic to and fro and on the peninsula? (This would be via the charming railroad bridge over the Cape Cod Canal.) A Barnstable County-wide bond issue to pay to extend sewerage? Close some golf courses

Llewellyn King: Big tech media monopolize ads, ravage journalism and act as global censors

At a Google advertising seminar in London in 2010

— Photo by Derzsi Elekes Andor

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The Department of Justice has filed suit against Google for its predatory advertising practices. Bully!

Not that I think Google is inherently evil, venal or greedier than any other corporation. Indeed, it is a source of much good through its awesome search engine.

But when it comes to advertising, Google, and the others with high-tech media platforms, most notably Facebook, have done inestimable damage. They have hoovered up most of the available advertising dollars, bankrupting much of the world’s traditional media and, thereby, limiting the coverage of the news — especially local news.

They have ripped the heart out of the economics of journalism.

Like other Internet companies, they treasure their own intellectual property while sucking up the journalistic property of the impoverished providers without a thought of paying.

While I doubt thatr the DOJ suit will do much to redress the advertising imbalance (Axios argues that the part of Google the DOJ wants divested only accounts for 12 percent of the company’s revenue), it will keep the issue of what to do about big tech media churning.

The issue of advertising is an old conundrum, written extra-large by the Internet.

Advertisers have always favored a kind of first-past-the-post strategy. In practice this has meant in the world of newspapers that a small edge in circulation means a massive gulf in advertising volume.

Broadcasting, through the ratings system, has been able to charge for the audience it gets, plus a premium for perceived audience quality — 60 Minutes compared to, say, Maury, which was canceled last year.

But mostly, it is always about raw numbers of readers, listeners and viewers. In a rough calculation, first past the post has meant 20 percent more of the audience turns into 50 percent more of the available advertising dollars.

I would cite The New York Times's leverage over the old New York Herald Tribune, The Baltimore Sun’s edge over the old News-American, and The Washington Post’s advantage over the old Evening Star. The weaker papers all in time folded even when they had healthy circulations, just not healthy enough.

Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc.,with their massive reach are killing off the traditional print media and wreaking havoc in broadcasting. This calls out for redress but it won’t come from the narrow focus of the DOJ suit.

The even larger issue with Google and its compatriots is freedom of speech.

The Internet tech publishers, for that is what they are, Google, LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook and others, reserve the right to throw you off their sites if you indulge in speech that, by contemporary standards, incites hate, violence or at least social disturbance.

Conservatives believe that they are victimized, and I agree. Anyone whose speech is restricted by another individual or an institution is a victim of prejudice, albeit the prejudice of good intent.

Recently, I was warned by LinkedIn that I would be barred from posting on the site because I had transgressed — and two transgressions merit banning. The offending item was an historical piece about a World War II massacre in Greece. The offense may have been a dramatic photograph of skulls, taken by my wife, Linda Gasparello, displayed in the museum at Distomo, scene of a barbarous genocide.

I followed the appeal procedure against the two-strikes-you’re-out rule, but I have heard nothing. I expect the censoring algorithms have my number and are ready to protect the public from me next time I write about an ugly historical event.

The concept of “hate speech” is contrary to free expression. It calls for censorship even though it professes otherwise. Any time one group of people is telling another, or even an individual, what they can say, free speech is threatened, the First Amendment compromised

The problem isn’t what is called hate speech but lying — a malady that is endemic in the political class.

The defense against the liars who haunt social media is what some find hateful speech: ridicule, invective, irony, satire, and all the other weapons in the literary quiver.

The right to bear the arms of free and open discourse shouldn’t be infringed by the social media giants.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Sam Pizzigati: The best case yet for raising taxes on billionaires

“Spirit of Ecstasy,” the bonnet ornament sculpture on Rolls-Royce cars, for which there were record sales last year.

— Photo by Jed

Via OtherWords. org

BOSTON

Sometimes the daily news about our billionaires just doesn’t make sense.

Last year, for instance, ended with a torrent of news stories about how poorly the world’s billionaires fared in 2022. Bloomberg tagged the 12 months that had just gone past “a year to forget,” with almost $1.5 trillion “wiped from the fortunes of the richest 500 alone.”

All global billionaires taken together, Forbes chimed in, lost $1.9 trillion in 2022. Some 148 of the world’s 2,671 billionaires even lost their billionaire status.

The year’s biggest billionaire losers? Some of America’s deepest pockets.

Larry Page saw his Google-driven fortune drop $40 billion. Mark Zuckerberg watched $78 billion evaporate off the wealth Facebook created for him. And Amazon’s Jeff Bezos had to swallow a minus $80 billion.

But honors for the biggest nosedive of all have to go to Elon Musk. The world’s richest man at the start of 2022, Musk ended the year losing both his top slot and some $115 billion from his personal fortune.

So did all these losses have our billionaires shaking in their boots? Did they start tightening their belts a bit in 2022? Spend less on the world’s most fabulously expensive luxuries?

Not exactly. In fact, not all.

The world’s most celebrated purveyors of pure extravagance actually registered record years in 2022. Rolls-Royce had its best-ever annual sales total, selling a record 6,021 “motor cars,” up 8 percent over 2021.

“Our clients,” Rolls-Royce’s CEO crowed on New Year’s Day, “are now happy to pay around half a million Euros for their unique motor car,” a sum equal to about $540,000 in the United States, the company’s single largest market.

“Our order book stretches far into 2023 for all models,” the Rolls-Royce chief added. “We haven’t seen any slowdown in orders.”

Lamborghini had an even better 2022, with 9,233 vehicles sold — a 10-percent jump over last year. The company’s biggest market? The United States. Americans drove off Lamborghini lots with 2,771 new cars in 2022. The automaker’s most popular model runs about a quarter-million.

Realtors who cater to the ultra-rich set had an equally boffo year in 2022.

In a down real-estate market, the highest of high-end residences still pulled in mega sums at closing time. The year’s top 10 home sales in the United States, notes the luxury-oriented Robb Report, “totaled roughly $1.165 billion, proving that, impending recession or not, luxury real estate will always be traded.”

How can all this luxury be? How can the richest of the rich be spending fantastic sums in a year when they’re seeing fantastic falls in their personal net worths?

Simple. In the realms of the super rich, losing a billion — or even many billions — makes no difference whatsoever in real daily life. Net worth down a few billion? You can still afford anything your heart could possibly desire.

No one alive today needs fortunes worth dozens of billions to live astoundingly large. A mere billion would suffice. So, truth be told, would a mere tenth of a billion. In the day-to-day lives of billionaires, a few billions or so have no practical significance — except when it comes to increasing their political power at the expense of the rest of us.

Taxing those billions to support the common good, on the other hand, could make an immeasurable difference in the lives of millions — and our democracy.

We need more than a dip in grand concentrations of private wealth. We need a world without billionaires.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

‘Complexity of space’

“Red Sunset Over Valley” (oil on canvas), by Boston-based artist Kimberly Druker Stockwell, in the group show “Light & Form: Northern Landscapes,’’ at the Women’s Rural Entrepreneurial Network, Bethlehem N.H. The others in the show are Jane Elfner and Chris Whiton.

Looking toward the White Mountains from Bethlehem’s Main Street in spring.

— Photo by Stevage

Ms. Stockwell explains:

“The White Mountains of New Hampshire are a frequent subject …. Painting en plein air, the work is less about rocks and trees as color and light. The patterns created by the natural rugged beauty are reflected on her canvases in a series of graceful brush strokes and scrape of the pallet knife; toying with appearance and reality. Paintings are built up with paint that is rubbed in, scraped off, and painted over, mimicking nature’s life cycle process. The result is a complexity of space and the unique quality of color that will not be found in a tube.’’

TD Garden will keep name at least to 2045

TD Garden, which was opened in 1995, when it was called the Fleet Center, after a disappeared New England bank.

TD Bank has renewed its agreement to keep its name on what many of us still call the Boston Garden, now officially the TD Garden, for an additional 20 years. Under TD Bank’s original 2005 agreement, its naming rights to the arena were set to expire in 2025, but that has now been extended to 2045. TD Bank is part of Toronto-based Toronto-Dominion Bank, a huge multinational financial-services company.

TD Bank will remain the official bank of the Boston Bruins until 2045. The Bruins’ home ice, of course, is at TD Garden. The Celtics are also based there. The bank is also committing $15 million to local programs, including free event tickets provided to people from underserved communities and funds to artists working on community projects.

In a 1994 photo, the old Boston Garden, built in 1928, and known for its smoky and gritty interior and occasional violations of the fire codes through overcrowding. A lot of people remember being taken there to see the Ringling Brothers circus. Ah, the smell of manure!

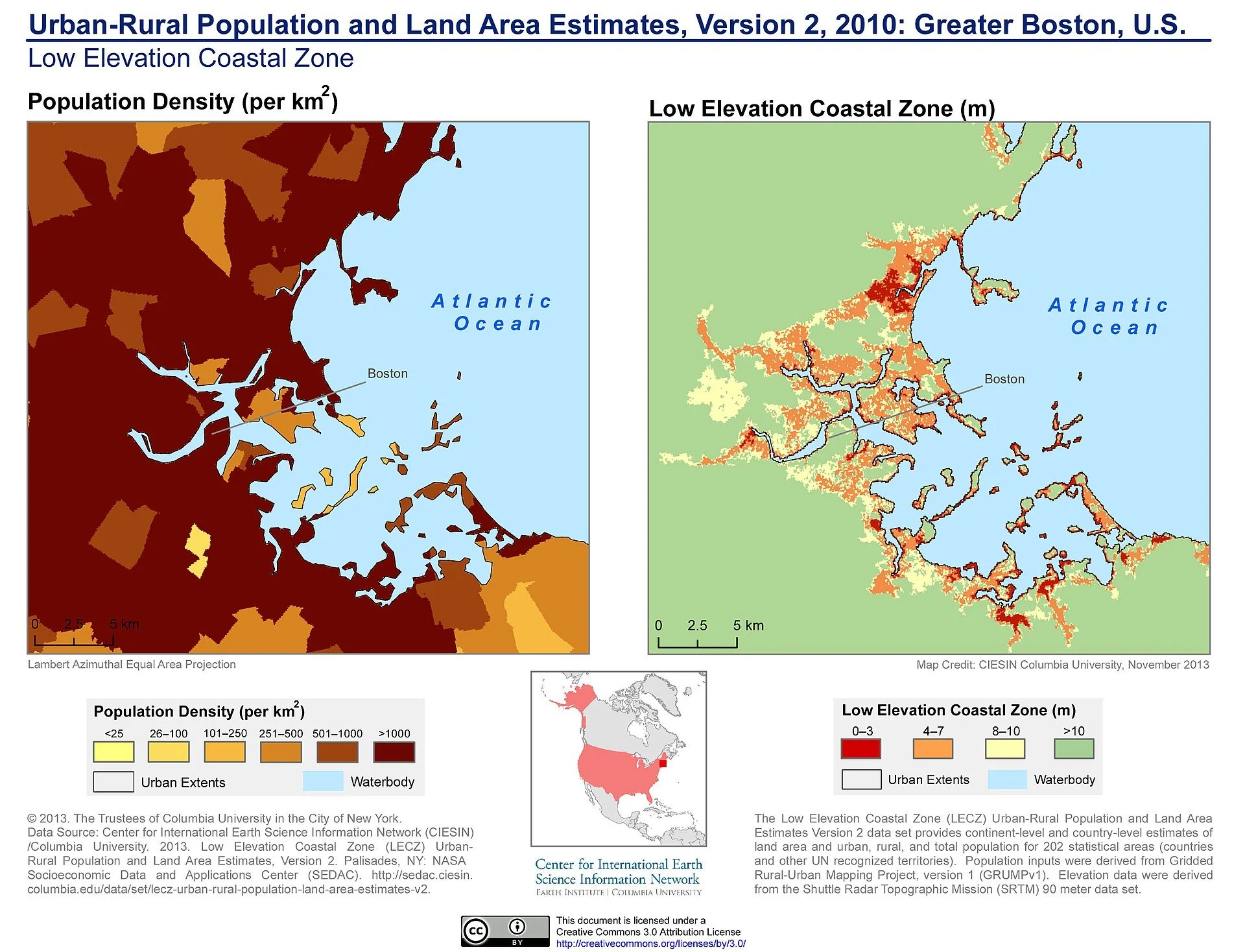

Llewellyn King: Rich nations must lead the way on the bumpy road to a green future

Rising seas caused by global warming threaten Greater Boston.

SEDACMaps - Urban-Rural Population and Land Area Estimates, v2, 2010: Greater Boston, U.S.

ABU DHABI, United Arab Emirates

I first heard about global warming being attributable to human activity about 50 years ago. Back then, it was just a curiosity, a matter of academic discussion. It didn’t engage the environmental movement, which marshaled opposition to nuclear and firmly advocated coal as an alternative.

Twenty years on, there was concern about global warming. I heard competing arguments about the threat at many locations, from Columbia University to the Aspen Institute. There was conflicting data from NASA and other federal entities. No action was proposed.

The issue might have crystallized earlier if it hadn’t been that between 1973 and 1989, the great concern was energy supply. The threat to humanity wasn’t the abundance of fossil fuels. It was the fear that there weren’t enough of them.

The solar and wind industries grew not as an alternative but rather as a substitution. Today, they are the alternative.

Now, the world faces a more fearsome future: global warming and all of its consequences. These are on view: sea-level rise, droughts, floods, extreme cold, excessive heat, severe out-of-season storms, fires, water shortages, and crop failures.

Sea-level rise affects the very existence of many small island nations, as the prime minister of Tonga, Siaosi Slavonia, made clear here at the annual assembly of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), an intergovernmental group with 167 member nations.

It also affects such densely populated countries as Bangladesh, where large, low-lying areas may be flooded, driving off people and destroying agricultural land. Salt works on food, not on food crops.

Sea-level rise threatens the U.S. coasts — the problem is most acute for such cities as Boston, New York, Miami, Charleston, Galveston and San Mateo. Flooding first, then submergence.

How does human catastrophe begin? Sometimes it is sudden and explosive, like an earthquake. Sometimes it advertises its arrival ahead of time. So it is with the Earth’s warming.

Delegates at the IRENA assembly felt that the bell of climate catastrophe tolls for their countries and their families. There was none of the disputations that normally attend climate discussions. Unity was a feature of this one.

The challenge was framed articulately and succinctly by John Kerry, U.S. special presidential envoy for climate. Kerry’s points:

—Global warming is real, and the evidence is everywhere.

—The world can’t reach its Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030 or the ultimate one of net-zero carbon by 2050 unless drastic action is taken.

—Warming won’t be reversed by economically weak countries but rather by rich ones, which are most responsible for it. Kerry said 120 less-developed countries produce only 1 percent of the greenhouse gases while the 20 richest produce 80 percent.

—Kerry, notably, declared that the technologies for climate remediation must come from the private sector. He wants business and private investment mobilized.

The emphasis at this assembly has been on wind, solar and green hydrogen. Wave power and geothermal have been mentioned mostly in passing. Nuclear got no hearing. This may be because it isn’t renewable technically. But it does offer the possibility for vast amounts of carbon-free electricity. It is classed as a “green” source by many government institutions and is now embraced by many environmentalists.

The fact that this conference has been held here is of more than passing interest. Prima facie, Abu Dhabi is striving to go green. It has made a huge solar commitment to the Al Dhafra project. When finished, it will be the world’s largest single solar facility. Abu Dhabi is also installing a few wind turbines.

Abu Dhabi has a four-unit nuclear power-plant at Barakah, with two 1,400-megawatt units online, one in testing and one under construction. Yet, the emirate is a major oil producer and is planning to expand its production from more than 3 million barrels daily to 5 million barrels.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has made oil more valuable, and even states preparing for a day when oil demand will drop are responding. Abu Dhabi isn’t alone in this seeming contradiction between purpose and practice. Green-conscious Britain is opening a new coal mine.

The energy transition has its challenges — even in the face of commitment and palpable need. The delegates who attended this all-round excellent conference will find that when they get home.

In the United States, utilities are grappling with the challenge of not destabilizing the grid while pressing ahead with renewables. Lights on, carbon out, is tricky.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. And he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

InsideSources

Water rising and receding

This ceramic work is in Judy Pfaff’s current show, “smokkfishkur,” at the Museum of New Art (MONA), in Portsmouth, N.H.

The museum says:

“Judy Pfaff's painting in space takes a step further at MONA. Here are themes here of water rising and also receding, themes of the sea, ice, especially Icelandic—smokkfiskur, the Icelandic word for ‘squid,’ serves up mysteries that hint at submerged life counterbalanced by life made newly visible….

“Life beneath the surface is a long, evolving theme of Pfaff's. Here, for the first time, she includes new exploration of ceramics. Collapsed and twisted, these pots merge with sea life relics as exposed marine sedimentary layers similar to the palimpsest play in her printworks….

”Water is changing our world. Sea levels are rising; arctic lakes are vanishing. This upwelling of ancient history and covert creatures also stokes joy and curiosity. While the front gallery displays undersea emergence, the middle gallery invites emotional immersion served up and brightly lit with ingenious imagination. The rear gallery teases with secrets. Here, above sea level, there are hints of glaciers and things that float, bleached by the sun or frozen and preserved.’’

Birchbark building

“Back of State and Main” (in Montpelier Vt.) (inkjet on birchbark), by Burlington, Vt.-based photographer Richard Moore, at The Front gallery, Montpelier, Vt., though Jan. 29.

Main Street in downtown Montpelier.

— Photo by GearedBull

Montpelier in 1884. Note the state capitol. The Winooski River enjoys flooding the city from time to time.

David Warsh: Defense of and attack on government debt

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Weary of reading play-by-play stories about the Treasury Department’s efforts to manage in light of the hold-up by right-wing Republicans over reaching the federal debt ceiling – impoundment decisions, discharge petitions and various accounting maneuvers – I took down my copy of Barry Eichengreen’s In Defense of Public Debt (Oxford, 2021) to remind me of what, at bottom, the fracas is all about.

Eichengreen, an economic historian at the University of California at Berkeley, is still not yet a household word in homes where economics is dinner-table conversation, though earlier this month he was named (with four others) a distinguished fellow of the American Economic Association, the profession’s highest honor.

He was recognized chiefly for having written Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression 1919-1939 (Oxford, 1992), which has become the standard account of how the Great Depression was so globally damaging – the role that the gold standard played in transmitting around the world its origins in the United States.

But it was sheer good citizenship that led Eichengreen and three other experts – Asmaa El-Ganainy, Rui Esteves and Kris James Mitchener – to write what their publisher describes as “a dive into the origins, management, and uses and misuses of sovereign debt through the ages.” Their Defense turns out. too, to be useful in looking ahead to what is said to be a looming crisis of global debt. .

Their book begins with another dramatic moment of American civic life: Sen, Rand Paul (R.-Ky.) inveighing in December 2020, against government borrowing earlier that year on news of the outbreak of the global Covid pandemic:

How bad is our fiscal situation? Well, the federal government brought in $3.3 trillion in revenue last year and spent $6.6 trillion, for a record-setting $3.3 trillion deficit. If you are looking for more Covid bailout money, we don’t have any. The coffers are bare. We have no rainy day fund. We have no savings account. Congress has spent all of the money.

Paul’s alarm was based on a fundamental insight, Eichengreen and his co-authors write, namely that governments are responsible for their nations’ finances. If they borrow frivolously, or excessively, bad consequences usually follow, On the other hand, if national governments fail to borrow in a genuine emergency – to fight a war deemed necessary; to staunch a financial panic; to facilitate a domestic political pivot – even worse damages might ensue. The sword is two-sided: Public debt has its legitimate uses, after all. .

A market for sovereign debt has existed for millennia. Kings and war-lords borrowed, most often to wage war. They paid exorbitant interest rates because they often defaulted. It was only in the 17th Century, as modern nations began to emerge, that viable institutions of public debt were established, first in England and the Netherlands.

Constitutional governments, with legislatures and parliaments, made it possible for would-be lenders to participate in decisions to borrow, to engineer realistic hopes of getting their money back, as they turned in the coupons they clipped from their government bonds in exchange for semi-annual payments of interest. Advice and consent became part of the game.

From the beginning, there was ambivalence. In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith himself warned that it would be all to easy for nations to borrow profligately against the promise of future tax revenues, Eichengreen noted. Smith made an exception mainly for war. As it turned out, the stabilization of British government debt markets organized by Robert Walpole after the disastrous South Sea Bubble, which popped in 1720, became the original military industrial complex. Many scholars credit superior borrowing capacity for Britain’s eventual victory in the Napoleonic Wars.

Government borrowing expanded to other purposes in the 19th Century, Eichengreen writes, especially for investments in canals and railroads intended to foster geographic integration and growth. Central banks learned how to halt financial panics by serving as lenders of last resort.

In the 20th Century, he says, the emphasis shifted again, this time to social services and transfer payments. Government borrowing financed the creation of the modern welfare state. And, of course, governments continue to shoulder the responsibility to maintain overall financial stability.

Today, the argument is between “conservative” radicals who hope to disassemble the welfare state, and radical “progressives,” who seek to expand it with little concern for the dangers of borrowing too much. In the center are a large corps of sensible citizens, such as Eichengreen, who seek to harness the existing system of taxing and borrowing and spending to let it work in a sensible and less expensive manner.

The market for government debt has survived, Eichengreen notes, “indeed thrived, for the better part of five hundred years.” It is an indispensable part of the world’s fiscal plumbing. Tinkering with it is fine; holding it hostage makes no sense at all. In Defense of Public Debt is an excellent primer on all these issues. I haven’t done it justice, but I started too late, and have run out of time.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Liability Lane

A noncollapsed part of Newport’s Cliff Walk.

— Photo by Giorgio Galeotti

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Will they soon have to patch and fill along and on Newport’s famous Cliff Walk every few months, what with rising seas and more intense storms? The latest drama came in a Dec. 23 tempest in which part of the walk’s embankment collapsed. A section of the walk itself collapsed last March in a storm.

Maybe they should change the name of this tourist attraction to Liability Lane.

But the big thing to watch in The City by the Sea is the redevelopment and, we hope, beautification, of the ugly North End.

Speaking of the tourist mecca of Newport, the country, including New England, will likely go into a recession this year, and unlike in the pandemic recession, the Feds can’t be expected to bail out the states. So the states better pump up their rainy-day funds. Rhode Island, for its part, should intensify its promotion of warm-weather tourism, especially in such nearby areas as Greater New York City, to get more sales tax revenue to help offset the decline in other tax revenue.

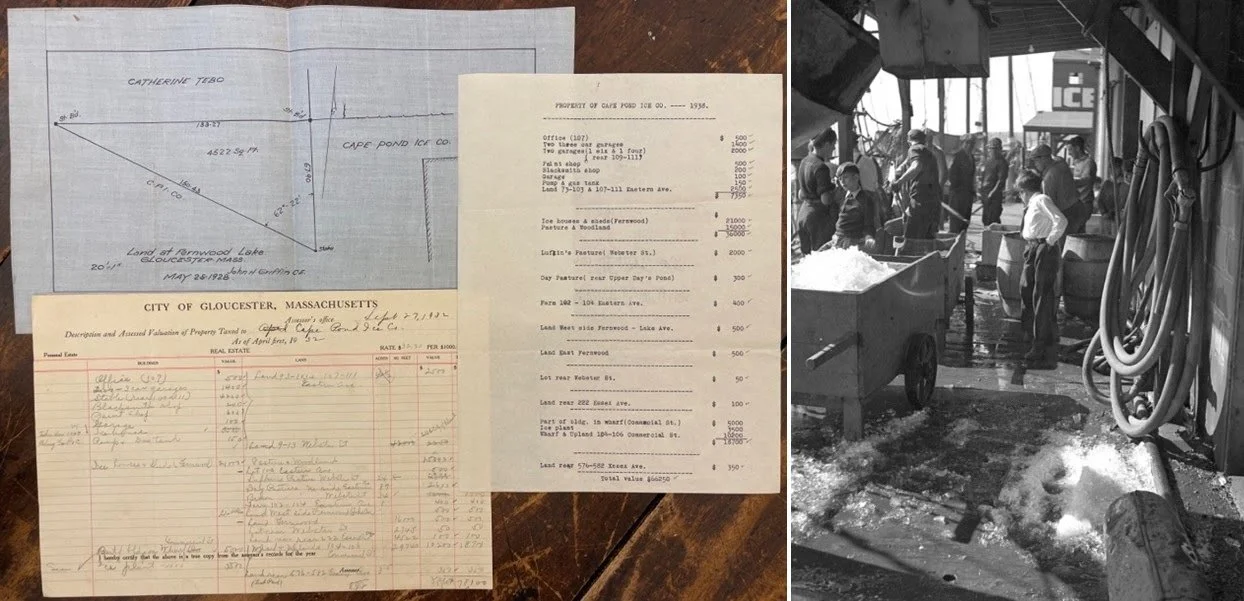

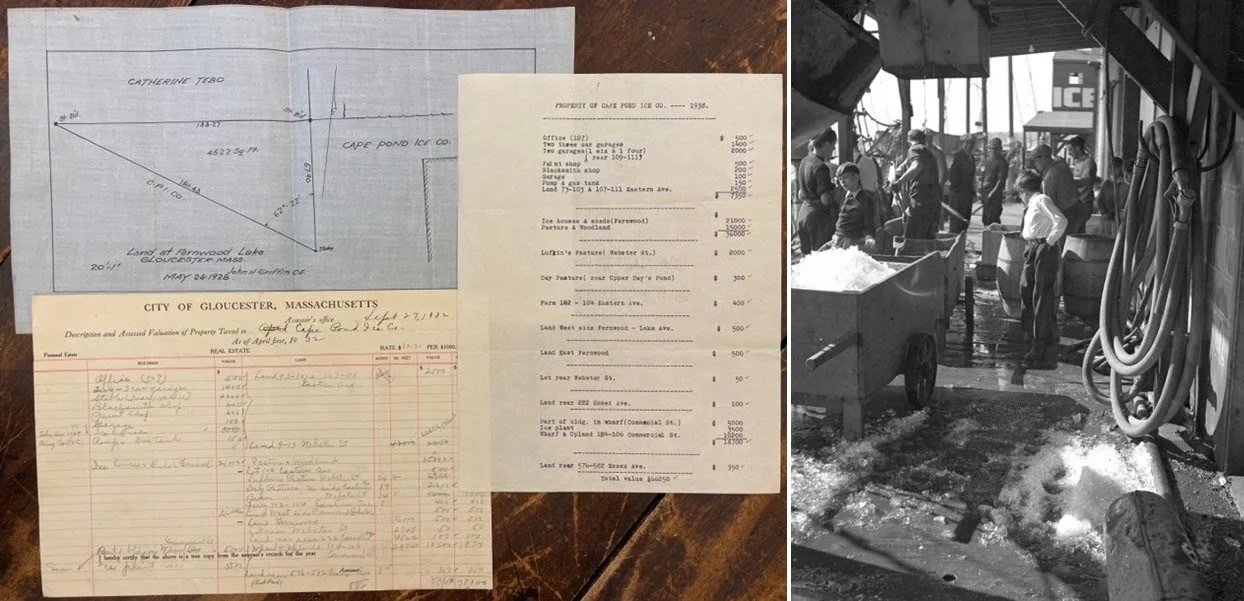

New England's icier past

At the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.: Left, items from the Cape Pond Ice Company Collection, including blueprints and listings of assets. Right, Cape Pond Ice Wharf, circa 1930s.

—Photo by Henry Williams

Winters were colder and longer in southern New England not that long ago, historically speaking. Ice was a major “crop,’’ with much of it shipped in sawdust to warmer climes, and many harbors froze up most winters, sometimes for weeks.