Some real and movie time with Pete Seeger

In the late spring of 1970, a group of about a dozen of us (I was along for the ride with a girlfriend of the time) spent a few hours with the mellow-voiced Peter Seeger at his 17-acre rustic homestead, in Beacon, N.Y., on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River. It had been a lush, warm spring, famous for anti-Vietnam War demonstrations. We had a cookout, at which Seeger was an affable host. He, of course, sang and played the five-string banjo, and a few others joined in making music.

Way down below on the river was a sloop that he owned that he was using in the early stages of leading a campaign to stop the likes of General Electric and other organizations from dumping toxins (some carcinogenic) into the river (which that day, despite its poisons, looked like 18th Century painting of the Rhine. Gorgeous!). It seems astonishing now to think of what we dumped into our public water, both as individuals and as institutions.

I generally disliked folk songs back then -- the lyrics seemed too sentimental and sometimes far too preachy and the tunes repetitive and clunky. I find them easier to take these days because I hear them as part of the broad flow of history. Or maybe I'm just getting hard of hearing....

Meanwhile, take a look at this segment of the very funny and sad movie The American Ruling Class. In it, Pete Seeger is walking, banjoing and singing down a road in what seems to be a very pastoral part of Greenwich, Conn., a capital of the sometimes rapacious capitalism that the old leftie hated. I think it's pretty funny, as is much of the movie, directed by John Kirby, produced by Libby Handros and with writer/editor Lewis Lapham as the master of ceremonies. He takes us to a lot of other celebrities commenting on American society in the years before the Great Crash of 2008.

Comment via rwhitcomb51@gmail.com

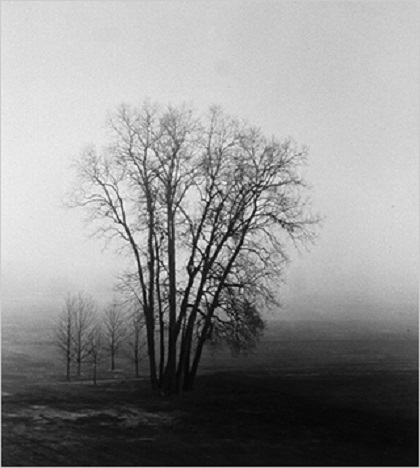

January thaw

Jan. 25, 2014 A windy, mild and sweetly melancholic day with scudding clouds from the southwest. Snow and ice are melting without man-made stimulants. Once again I'm rather surprised and pleased by how the light is brighter in late January than even just a couple of weeks before, and by the power of even the winter sun to quickly heat us in sheltered places. Our unheated but glassed-in sleeping porch, which faces the south, gets up to 75 even when it's 15 outside. We use the space to heat the adjoining bedroom by day.

We New Englanders could do a lot more with passive solar heating. It's not as if we're that far north; we're at the latitude of Portugal.

One nice thing about aging is that while the cold itself is harder to take, especially the windy chill of Northeast coastal cities, you're ever more aware of how fast time goes -- it will be spring very soon. And while it has seemed recently that we're living on Hudson's Bay, actually we're much closer to the Gulf Stream.

In New England, more than in most places, we have the weather to help mark off sections of our lives, as an aide-memoire, and that's handy. Now we have the predictable "January thaw,'' which, though this one will be very brief, reminds us that our weather won't really be paralyzed by the likes of "polar vortexes'' or other such Weather Channel monsters. By the way, California is having record heat and drought. And Alaska has been pretty warm for, well, Alaska.

Scientists differ on why the rise in temperatures associated with the "January thaw' ' tends to happen in late January rather than in early February, which would seem to make more sense. In any case, I'm more vulnerable to the sadness from lack of light than from the cold. And the light is moving in the right direction.

comment via rwhitcomb51@gmail.com

Tools of a brutal trade

The University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth's gallery at 715 Purchase St., New Bedford, will present "The Harpoon Project and the Legacy of Lewis Temple'' on Jan. 29, at 6-8 p.m.

The University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth's gallery at 715 Purchase St., New Bedford, will present "The Harpoon Project and the Legacy of Lewis Temple'' on Jan. 29, at 6-8 p.m.

Mr. Temple was an African-American abolitionist and inventor. He invented the toggle harpoon in 1848 -- another way to torture whales but nice for the industry, which by that point was already in decline.

Panelists include Carl Cruz, of the New Bedford Historical Society, Michael Dyer, of the New Bedford Whaling Museum, Janine da Silva, of the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, and Linda Whyte Burrell, an artist. The panel will be moderated by Marc Levitt, of the "Action Speaks'', an NPR radio show based in Providence.

Blighted and bright college days

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com) is a Providence-based editor and writer.

The ultimate respect?

"Odalisque,'' by ELMYR de HORY (1974, oil on canvas), in the style of Henri Matisse. Collection of Mark Forgy. (Photo by Robert Fogt ) at the Michele and Donald D'Amour Museum of Fine Arts, in Springfield, Mass. through April 27. It's in the "Deceive: Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World'' show.

Most of us are fakers in some way, and we build upon the work of others, albeit not usually to the point of trying to perfectly replicate it to show off and/or make money. This brilliant show will test the perceptions of authenticity and, the museum says, show how technology is used to determine fraud.

David Warsh: WWI, the elites and the 2008 crash

By DAVID WARSH

BOSTON

A century after the outbreak of World War I, in 1914, and the memory of the wholly unexpected series of horrors to which it led, many commentators are feeling a little gloomy. Ordinarily I am persuaded by whatever sensible, knowledgeable, well-connected Martin Wolf has to say.

So I was surprised last week to find the chief economics columnist for the Financial Times arguing that our future is once again threatened by ignorant elites, just as it was in the years after 1914. This time, he wrote, the best and the brightest have been mismanaging the peace rather than bungling a war and its aftermath.

Wolf’s bill of particulars: First, the economic, financial, intellectual and political elites mostly misunderstood the consequences of headlong financial liberalization. Lulled by fantasies of self-stabilizing financial markets, they not only permitted but encouraged a huge and, for the financial sector, profitable bet on the expansion of debt. The policy making elite failed to appreciate the incentives at work and, above all, the risks of a systemic breakdown.

When it came, the fruits of that breakdown were disastrous on several dimensions: economies collapsed; unemployment jumped; and public debt exploded.

The policymaking elite was discredited by its failure to prevent disaster. The financial elite was discredited by needing to be rescued. The political elite was discredited by willingness to finance the rescue. The intellectual elite – the economists – was discredited by its failure to anticipate a crisis or agree on what to do after it had struck.

The rescue was necessary. But the belief that the powerful sacrificed taxpayers to the interests of the guilty is correct.

It seems to me that the history of the last 40 years is susceptible to a very different interpretation:

That the Cold War, which began with the partition of Europe after 1945 and the Communist Revolution in China in 1949, entered its last phase with the five-day meeting of the ruling committees of the Chinese Communist Party in December 1978, little more than two years after the death of Mao Zedong;

That the financial liberalization in the West, in the U.S. in particular, began just in time, in the Seventies, to facilitate the entry of China into the global market system, starting in 1979;

That markets in the Eighties in general coped very well with a vast expansion of world trade; and that the immediate aftermath of the Cold War saw remarkably little loss of life, except in the Balkans;

That experts in the Nineties navigated a series of crises in Mexico, in Asia, in Brazil and Argentina, preserving the international financial system and maintaining global growth;

That when the 25-year boom ended, in 2008, with the threat of a systemic breakdown of terrifying proportions, thanks to a global banking system that had evolved in ways that were little understood, central bankers correctly diagnosed the panic and Congress passed its test, appropriating funds necessary to preserve the banking system.

At least in the U.S., the necessary rescue probably cost the taxpayer little or nothing. The loans have been repaid. The severe losses – homes, jobs, earnings, careers, the fisc – stemmed from the deep recession, which otherwise could have been much worse. (The continuing crisis in the Eurozone is another matter. So is the Middle East.) True, by hampering the Fed’s ability to act, the Dodd-Frank Act probably makes it harder, not easier, to deal with the next crisis. But there is still time to deal with that.

I’d like to think that Wolf was simply writing for his audience, which consists almost entirely of those elites whom he castigates. There’s nothing wrong with leaning against the preferences of your readers. He cited weakening bonds of citizenship amid growing inequality and the constitutional disorder of the Eurozone as further evidence that elites are losing touch..

It seems to me more reasonable to fear that the rise of China and India to superpower status may cause increasing friction with their neighbors and with the West. The experience of World War I suggests that there may be something about coming into the club that wants a war. That was the case with Prussia’s becoming Germany, and Russia’s designs on the Ottoman Empire in the run-up to August, 1914. This time the problem of climate change may be enough to keep the lid on.

Some pretty serious trials lie ahead.

David Warsh, an economic historian and long-time financial journalist, is principal of www.economicprincipals.com.

The Winslow Homer Studio

Winslow Homer's paintings have long been some of the most beloved art associated with New England. Thus many will want to visit the Winslow Homer Studio, at Prouts Neck, Maine. The studio, owned by the Portland Museum of Maine, is where the artist lived from 1883 until his death, in 1910. The museum says the studio is meant to "celebrate the artist's life, to encourage scholarship on Homer, and to educate audiences to appreciate the artistic heritage of Winslow Homer and Maine.''

Not that Homer is always that cheery. Many of his images show nature to be menacing, as in the painting "Northeaster'' below.

Blighted and bright college days

A troubled beauty

Manmade beauty within natural beauty -- but not refuges from reality. That's what William Morgan has described in his new book, with gorgeous photos by Trevor Trento: "A Simpler Way of Life: Old Farmhouses of New York & New England'', published by Norfleet Press and selling for $49.59. This book itself can be a heirloom.

Mr. Morgan, a distinguished architectural historian, has written a text that does not sugarcoat the tough and uncertain lives led by many farmers, especially when most of these farmhouses were built, in inland, upland New England and New York State, in the late 18th Century and well into the 19th.

The farmers were constantly at the mercy of the weather, far-away market forces and other factors over which they had no control. The book is informed by a deep understanding of the architectural, social and economic history, and life today, of the rural part of our corner of North America.

Messrs. Morgan and Mr. Trento implicitly make the argument that the old country house can be as beautiful as any mansion, while evoking more humanity. There's a poignancy about these old houses.

But, my God, they sure can be hard to heat and maintain!

Laying a glove on Seekonk

Chris Powell: Get paid to hire back those you fired

By CHRIS POWELL Maybe other big employers in Connecticut will get an idea from the state Economic and Community Development Department's latest excursion into corporate welfare. Last March ClearEdge Power Corp., owner of the former United Technologies Corp. fuel-cell factory in South Windsor, laid off more than 100 employees. But this week state government loaned the company $1.4 million at a deeply discounted rate, with about half the loan to be forgiven if the company adds 80 employees over three years. Rehiring employees laid off in March will count toward the total of new employees to be added to achieve loan forgiveness. So in Connecticut you now can lay off your workers and then get money from state government for hiring them back. The economic development commissioner, Catherine Smith, explains this as a plan to induce ClearEdge to expand in Connecticut rather than at its facilities in Oregon and California. But the plan will work only at the expense of inviting more big employers to blackmail state government -- not just by threatening to move but also by laying off employees and then demanding that state government ransom them. While the Democratic Party still poses as the party of working people, the “economic development” policy of Connecticut's Democratic administration takes from the poor to give to the rich. Big employers have blackmail power; small employers don't. So small employers and their employees pay more in state taxes to subsidize bigger companies and their employees. Yes, many states are subsidizing big employers this way and inducing subsidy competitions with other states. But since subsidies to big business come at the expense of small business, both in taxes and general competitive disadvantage, the best economic development policy still is a tax and regulation regime that is favorable to all businesses without regard to size. Connecticut's unattractiveness to business and residents alike did not arise from a lack of subsidies to particular businesses but rather from the failure of government generally to provide value even as it has grown and become more expensive. That is, education policy has not been producing more or better education but mainly has just been enriching educators. Welfare policy has not reduced poverty and enabled and required people to start supporting themselves but rather has worsened dependence and anti-social behavior. Connecticut's government employee policies practically forbid ordinary public administration. And so forth. Connecticut's big problem is that the premises of some of its major policies are mistaken or, really, mere pretexts for parasitism. * * * According to a recent study by the state Office of Policy and Management, as reported by the Waterbury Republican-American, revenue foregone by state tax exemptions totals nearly half of state government's tax revenue -- $7 billion in tax breaks against $15.3 billion in receipts. While some broad exemptions may be sensible and command wide support, like the exemption of food from the sales tax, many exemptions are obscure and the product of special pleading or pandering, like the celebrated exemption for clothing and footwear. Legislators propose dozens of such tax breaks every year and some become law, like the one enacted last year to give tax credits for restoring historic houses. Apart from basic decency, which explains the food exemption, there may be only one justification for tax exemptions: efficiency, as when application of a general tax to a specific transaction will forfeit more money than it raises, by driving business out of state. By that standard state government probably could raise billions of dollars or finance billions in general tax reduction by repealing many less compelling tax exemptions. But it has been many years since Connecticut has been able to appropriate that much political courage. Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer in Manchester, Conn.

Better without the players

"First Tee,'' by DIANNE BUNIS, at Gallery Seven, in Maynard, Mass.

She specializes in large-format black and white photography of the New England landscape, using the Zone System.

With the decline of farming, golf courses are some of the few remaining open stretches of green (or brown) open land in much of the Northeast. That's nice, although they'd look better if they had animals grazing on them. They're wonderful to run in, in the winter.

Something to look forward to

"Redbud Tree in Bottomload,'' photo by ELIOT PORTER, at the Portland Museum of Art (but photo is copyrighted by Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Forth Worth) in the Portland Museum's show "American Vision: Photographs from the Collection of Owen and Anna Wells''.

Please comment via rwhitcomb51@gmail.com

Jan. 7, 2014

Cold morning today but far from the "polar vortex'' catastrophe that it's being made out to be by the news media because their denizens think that nothing much else is going on. Of course, lots of stuff is going on but it bores those reporters and editors who haven't yet been laid off in the ferment caused by the triumph of mostly ''free'' information on the Internet. And maybe the public doesn't care all that much either.

Most importantly, "polar vortex'' sounds like a horror-movie monster. Very sexy. More vortexes to come because global warming is screwing up the jet stream? Too early to say with scientific assurance.

It's all rather typical of January, the coldest month. But February is often the snowiest because warm wet air begins to edge north again, setting up conflict with the cold air. Great for creating Nor'easters! Arctic air and the Gulf Stream can be in explosive proximity.

As I walked the dog this morning I enjoyed the crunch of my feet on the thin layer of snow that had fallen overnight as the front swung through from Canada, bringing a snow squall or two. And the frozen trees were creaking. Too cold to be slippery! The problem in the coastal Northeast is the wind. It can make urban walking miserable. When I lived in the Upper Connecticut River Valley, the temperature could be much colder than in Boston, Providence, New York and Philadelphia but the comfort level much higher because there was much less wind and it was very, very dry. Sort of exhilarating -- bright and almost antiseptically clean.

Meanwhile, along the lines of ever-more "nurturing'' of children by parents and schools (at the ones I attended we were often called by our last names and there wasn't much open concern for our feelings), is the practice of clothing our dogs for winter walks, even outside of the Upper East Side of Manhattan. I must confess that my wife and I have adopted this habit. The dog, a rescue mutt from San Antonio (via "Alamo Rescue''), fought having a coat on at the start but has since accepted it -- especially when it's windy.

My most physically painful memories of winter are in the streets of big cities with the northwest wind squeezing between the high buildings.

When it's really, really cold, ice is so sticky that you don't even worry about driving up and down steep snow-covered hills. A few times I had to drive my drunken mother to a drying-up spa at a place called Beech Hill Farm, on top of a mountain in Dublin, N.H. -- the little town where Yankee magazine was, and is, put out and where Mark Twain spent some happy times. If it was the winter, I'd pray for very cold weather. Around freezing was the most insidious, with a thin layer of melting in the sun, then quick refreezing toward evening.

The dramatic freeze-thaw cycles in New England make skiing more, well, exciting here than on the dusty, dry "powder snow'' promoted by resorts in the Rockies. Skiing in the White and Green mountains is much more of a challenge to muscles and nerves than is skiing at, say, Taos.

Anyway, I long for late February, when sun-facing cars and rooms suddenly seem to start to warm up much faster as the sun gets stronger. Even on a very cold day last week, I found the stone on a southwest-facing wall remarkably warm. We really do need to do a lot more with passive solar heating.

'Pretty white gloves'

By PAUL STEVEN STONE

CAMBRIDGE

He sits on a folded-over cardboard box, slightly off-balance and without any visible sign of support other than the granite wall of the bank behind him and the few coins in the paper cup he shakes at each passerby.

Does he realize it is 4 degrees above zero, or minus 25 degrees if you factor in the wind that blows through the city and his bones with little concern for statistics? Does he notice the thick cumulus lifeforms that escape from his mouth in shapes that shift and evanesce like the opportunities that once populated his life?

Can he even distinguish the usual numbing effect of the cheap alcohol from the cruel and indifferent caress of this biting alien chill?

Too many questions, he would tell you, if he cared to say anything. But his tongue sits in silence behind crusted chapped lips and chattering teeth while half-shut eyes follow pedestrians fleeing from the bitter cold and his outstretched cup.

His gaze falls upon the hand holding the cup as if it were some foreign element in his personal inventory. Surprised at first to find it uncovered and exposed, especially in weather this frigid, he now recalls that someone at the shelter had stolen his gloves and left in their place the only option he still has in much abundance.

Acquiescence.

Examining the hand, and the exposed fingers encircling the Seven-Eleven coffee cup, he smiles in amused perplexity, murmuring to himself, “White gloves.”

Lifting his hand for closer inspection, he adds, “Pretty white gloves.”

An image of his daughter . . . Elissa, he thinks her name was . Yes, Elissa!, he recalls. An image of Elissa rises up in his mind, from a photograph taken when she was ten and beautifully adorned in a new Easter outfit: black shoes, frilly lavender dress and hat and, yes, pretty white gloves. The photo once sat on a table in his living room, but he couldn’t tell you what happened to it, nor to the table or the living room, for that matter. They were just gone. Swept away in the same tide that pulled out all the moorings from his life, and everything else that had been tethered to them.

The last time he’d seen Elissa she was crying, though he no longer remembers why. Must have been something he’d done or said; that much he knows.

“Pretty white gloves,” he repeats, staring at his hand.

He recalls the white gloves from his Marine dress uniform. At most he wore them five times: at his graduation from officer’s training school, at an armed services ball in Trenton, New Jersey, and for three military funerals. There was never a need for dress gloves in Vietnam. They would have never stayed white anyway; not with all the blood that stained his hands.

Out of the corner of his eye he can see a policeman walking towards him and instinctively hides his cup, some vestige of half-remembered pride causing him to avert his gaze from the man’s eyes at the same time.

“We need to get you inside, buddy,” the officer says. “You’ll die of cold, you stay out here.”

Moments later, a second police officer, this one a woman, steps up to join them.

“That’s the Major,” she tells her colleague. To the seated figure she offers a smile.

“You coming with us, Major?”

“Go away,” he answers, looking up as he leans further against the cold granite wall. “Don’t need you. Don’t need no one.”

“Can’t leave you out here,” the first officer says. “We’ve got orders to bring you and everyone else in.”

“Leave me alone!” the seated man shouts, gesturing with his hands as if he could push them both away.

“Oh shit,” the female officer says under her billowing breath. To her partner she whispers, “His hands. Look at his hands.”

Quickly recognizing the waxy whiteness for what it is, the officer shrugs, “Guess we’re a little late.”

To the man on the sidewalk, he offers, “That’s frostbite, buddy.”

“No,” the seated man protests. He holds up both hands, numb and strange as they now feel and offers a knowing smile of explanation.

Just like the Marine officer he once was, just like the sweet innocent daughter he once knew, just like the young man grown suddenly old on a frozen sidewalk, his hands are beautiful and special in a way these strangers will never understand.

“White gloves,”he insists proudly.

“Pretty white gloves.”

Paul Steven Stone is a Cambridge-based writer. His blog, from which this comes, is www.paulstonesthrow.com.

Public-sector embarrassments

From HELEN PAYNE'S show "Here I Sit, Brokenhearted" at the Bromfield Gallery, Boston.

The gallery says her show is an " installation on bathroom tiles where drawings make visceral vignettes, showing moments ranging from giving birth to getting booked. A shape-shifting protagonist emerges from the tiles. She morphs in time and race and limps along at odds with expectations but at one with viscera.''

It's "about the ill fit of the body and how our most private moments can play out in the public sphere.''

Our private moments playing out in the private sphere can be bad enough.