Vox clamantis in deserto

Kent Jones: Trump’s lust for tariff power threatens economic democracy and encourages corruption

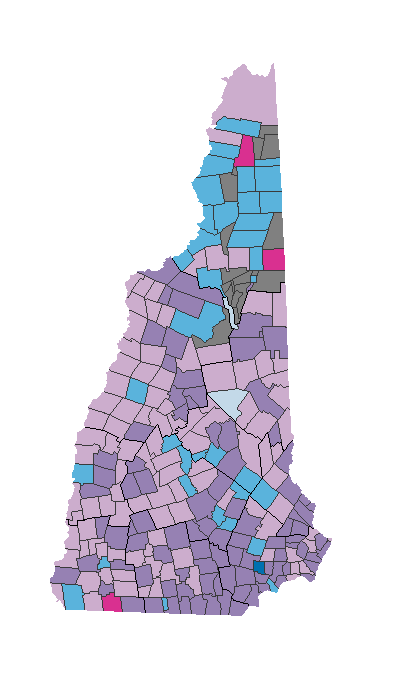

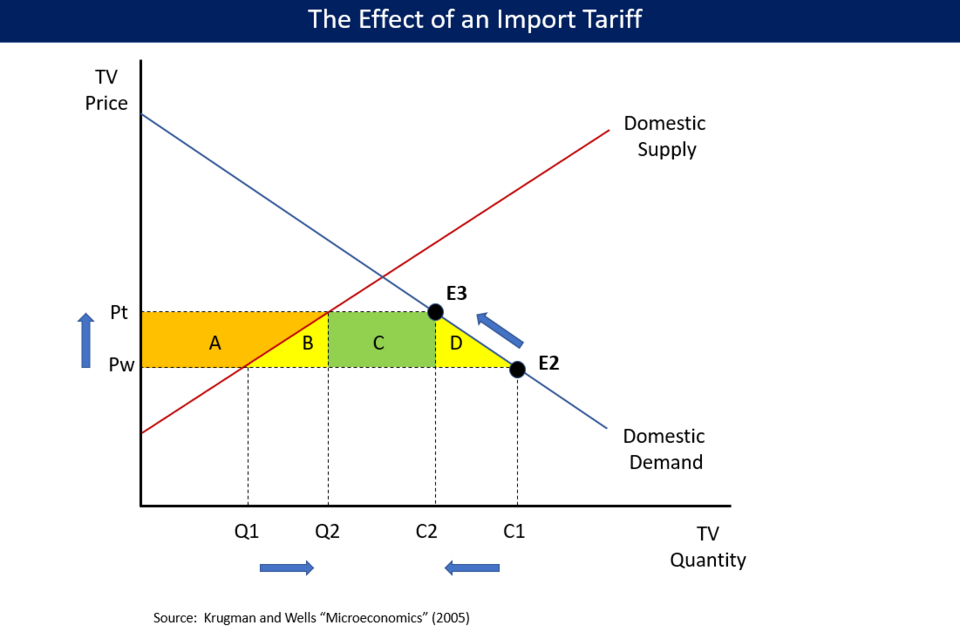

Effects of an import tariff, which hurts domestic consumers more than domestic producers are helped. Higher prices and lower quantities reduce consumer surplus by areas A+B+C+D, while expanding producer surplus by A and government revenue by C. Areas B and D are dead-weight losses, surplus lost by consumers and overall.

— From Wikipedia

From The Conversation, except image above

Kent Jones is a professor emeritus of economics at Babson College, in Wellesley, Mass.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The future of many of Donald Trump’s tariffs are up in the air, with the Supreme Court expected to hand down a ruling on the administration’s global trade barriers any day now.

But the question of whether a policy is legal or constitutional – which the justices are entertaining now – isn’t the same as whether it’s wise. And as a trade economist, I worry that Trump’s tariffs also pose a threat to “economic democracy” – that is, the process of decision-making that incorporates the viewpoints of everyone affected by the decision.

Founders and economic democracy

In many ways, the U.S. founders were supporters of economic democracy. That’s why, in the U.S. Constitution, they gave tariff- and tax-making powers exclusively to Congress.

And for good reason. Taxes can often represent a flash point between a government and its people. Therefore, it was deemed necessary to give this responsibility to the branch most closely tied to rule of, and by, the governed: an elected Congress. Through this arrangement, the legitimacy of tariffs and taxes would be based on voters’ approval – if the people weren’t happy, they could act through the ballot box.

To be fair, the president isn’t powerless over trade: Several times over the past century, Congress has passed laws delegating tariff-making authority to the executive branch on an emergency basis. These laws gave the president more trade power but subject to specific constitutional checks and balances.

Stakes for economic democracy

At issue before the Supreme Court now is Trump’s interpretation of one such emergency measure, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977.

Back in April 2025, Trump interpreted the law – which gives the president powers to respond to “any unusual and extraordinary threat” – to allow him to impose tariffs of any amount on products from nearly every country in the world.

Yet the act does not include any checks and balances on the president’s powers to use tariffs and does not even mention tariffs among its remedies. Trump’s unrestrained use of tariffs in this way was unprecedented in any emergency action ever taken by a U.S. president.

Setting aside the constitutional and legal issues, the move raises several concerns for economic democracy.

The first danger is in regards to a concentration of power. One of the reason tariffs are subjected to congressional debate and voting is that it provides a transparent process that balances competing interests. It prevents the interests of a single individual – such as a president who might substitute his own interests for that of the wider public interest – from controlling complete power.

Instead it subjects any proposed tariffs to the open competition of ideas among elected politicians.

Compare this to the way Trump’s tariffs were made. They were determined in large part by the president’s own political score-settling with other countries, and an ideological preference for trade surpluses. And they were not authorized by Congress. In fact, they bypassed the role of Congress as a check and balance – and this is not good for economic democracy in my view.

A protester holds a sign as the U.S. Supreme Court hears arguments on President Donald Trump’s tariffs on Nov. 5, 2025. Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

The second danger is uncertainty. Unlike congressional tariffs, tariffs rolled out through the International Emergency Economic Powers Act under Trump have been altered many times and can continue to change in the future.

While supporters of the president have argued that this unpredictability gives the U.S. a bargaining advantage over competitor nations, many economists have noted that it severely compromises any goal of revitalizing American industries.

This is because both domestic and foreign investment in U.S.-based industries depends on stable and predictable import-market access. Investors are unwilling to make large capital expenditures over several years and hire new workers if they think tariff rates might change at any time.

Even in the first year of the Trump tariffs, there is evidence of large-scale reductions in hiring and capital investment in the manufacturing sector due to this uncertainty.

The third danger concerns that lack of accountability involved in circumventing Congress. This can lead to using tariffs as a stealth way of increasing taxes on a population.

Importing companies generate revenue for the government through the additional levies they pay on goods from overseas. These costs are typically borne by domestic consumers, through increased prices, and importing companies, through lower profit margins.

Either way, Trump’s International Emergency Economic Powers Act interpretation has allowed him to use tariffs in a way that would – if allowed to stand – bring in additional government revenue of more than US$2 trillion over a 10-year period, according to estimates.

Trump frames the revenue his tariffs have raised as a windfall of foreign-paid duties. But in fact, the revenue is extracted from domestic consumer pockets and producer profit margins. And that amounts to a tax on both.

Corruption concerns

Finally, the way Trump’s used the act to roll out unilateral and changeable tariffs creates an incentive for political favoritism and even bribery.

This is down to what economists call “rent seeking” – that is, the attempt by companies or individuals to get extra money or value out of a policy through influence or favoritism.

As such, Trump can, should he wish, play favorites with “priority” industries in terms of tariff exemptions. In fact, he has already done this with major U.S. companies that import cell phones and other electronics products. They asked for special exemptions for the products they imported, a favor not granted to other companies. And there is nothing stopping recipients of the exemptions offering, say, to contribute to the president’s political causes or his renovations to the White House.

Smaller and less politically influential U.S. businesses do not have the same clout to lobby for tariff relief.

And this tariff-by-dealmaking goes beyond U.S. companies looking for relief. It extends into the world of manipulating governments to bend to Washington’s will. Unlike congressional tariffs under World Trade Organization rules, International Emergency Economic Powers Act tariffs discriminate from country to country – even on the same products.

And this allows for trade deals that focus on extracting bilateral deals that take place without considering broader U.S. interests. In the course of concluding bilateral Trump trade deals, some foreign governments such as Switzerland and South Korea have even offered Trump special personal gifts, presumably in exchange for favorable terms. Presidential side deals and gift exchanges with individual countries are, as many scholars of good international governance have noted, not the best way to conduct global affairs.

The harms of having a tariff system that eschews the normal checks and balances of the American system are nothing new, or at least shouldn’t be.

Back in the late 1700s, with the demands of a tyrannical and unaccountable king at the front of their minds, the founders built a tariff order aimed at maintaining democratic legitimacy and preventing the concentration of power in a single individual’s hands.

A challenge to that order could have worrisome consequences for democracy as well as the economy.

Kent Jones: The taxes that are called tariffs — some history and who gets hit

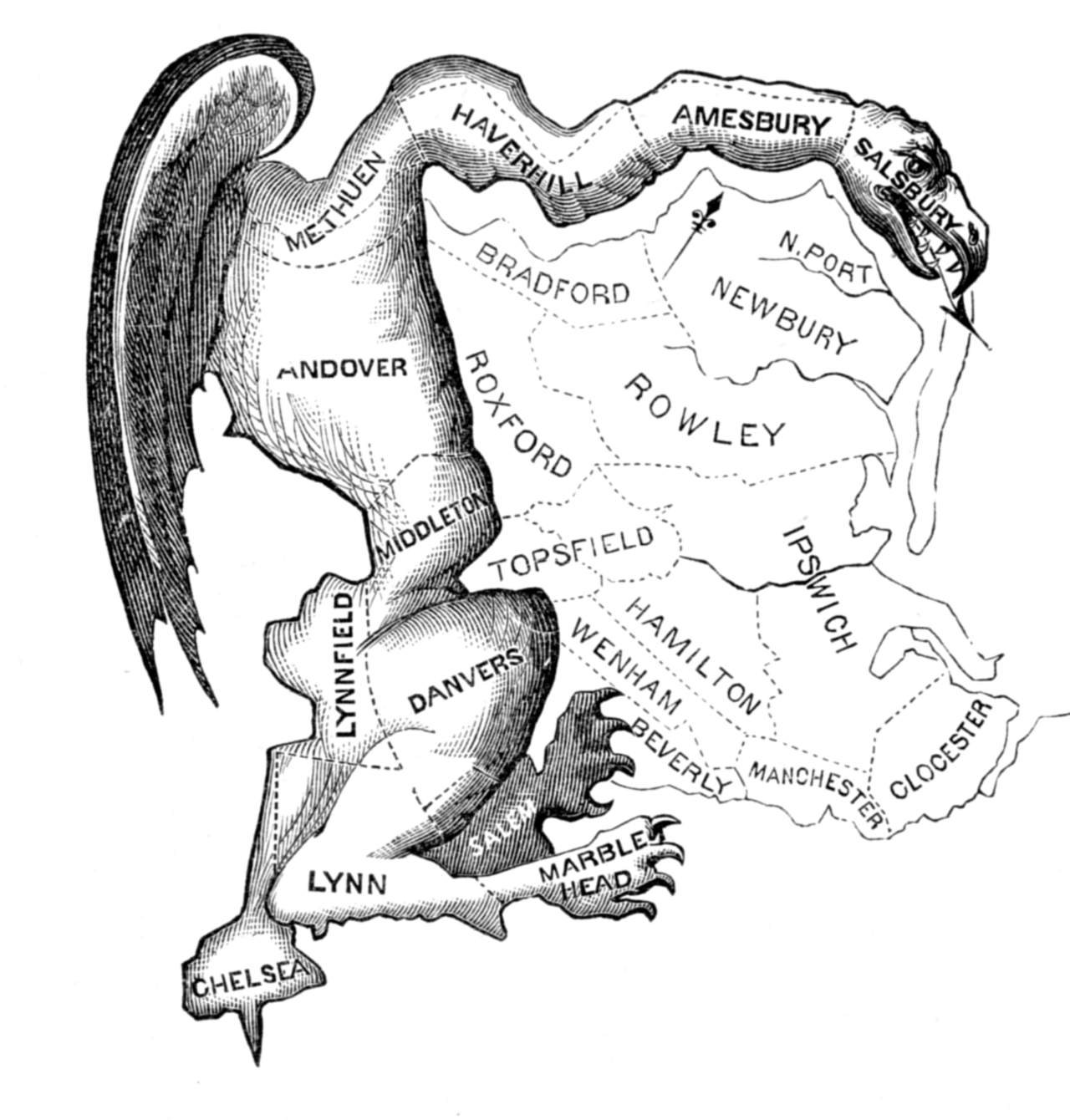

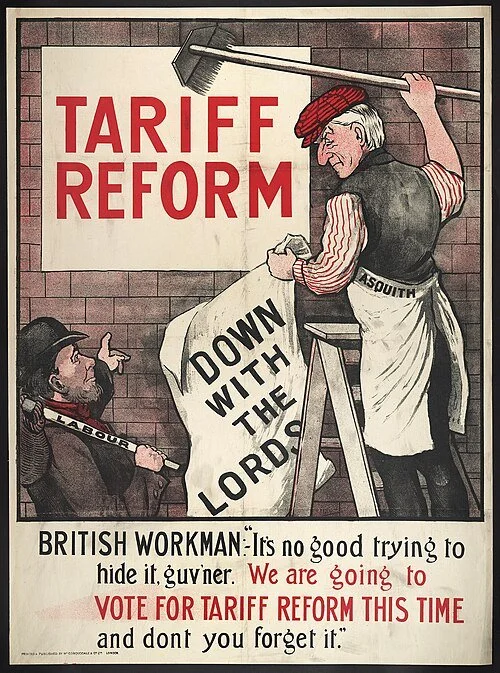

Cartoon from around 1900.

From The Conversation (except for images above)

Kent Jones is a professor emeritus of economics at Babson College, Wellesley, Mass.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The U.S. Supreme Court is currently reviewing a case to determine whether President Donald Trump’s global tariffs are legal.

Until recently, tariffs rarely made headlines. Yet today, they play a major role in U.S. economic policy, affecting the prices of everything from groceries to autos to holiday gifts, as well as the outlook for unemployment, inflation and even recession.

I’m an economist who studies trade policy, and I’ve found that many people have questions about tariffs. This primer explains what they are, what effects they have, and why governments impose them.

Who pays them?

Tariffs are taxes on imports of goods, usually for purposes of protecting particular domestic industries from import competition. When an American business imports goods, U.S. Customs and Border Protection sends it a tariff bill that the company must pay before the merchandise can enter the country.

Because tariffs raise costs for U.S. importers, those companies usually pass the expense on to their customers by raising prices. Sometimes, importers choose to absorb part of the tariff’s cost so consumers don’t switch to more affordable competing products.

However, firms with low profit margins may risk going out of business if they do that for very long. In general, the longer tariffs are in place, the more likely companies are to pass the costs on to customers.

Importers can also ask foreign suppliers to absorb some of the tariff cost by lowering their export price. But exporters don’t have an incentive to do that if they can sell to other countries at a higher price.

Studies of Trump’s 2025 tariffs suggest that U.S. consumers and importers are already paying the price, with little evidence that foreign suppliers have borne any of the burden. After six months of the tariffs, importers are absorbing as much as 80% of the cost, which suggests that they believe the tariffs will be temporary. If the Supreme Court allows the Trump tariffs to continue, the burden on consumers will likely increase.

While tariffs apply only to imports, they tend to indirectly boost the prices of domestically produced goods, too. That’s because tariffs reduce demand for imports, which in turn increases the demand for substitutes. This allows domestic producers to raise their prices as well.

A brief history of tariffs

The U.S. Constitution assigns all tariff- and tax-making power to Congress. Early in U.S. history, tariffs were used to finance the federal government. Especially after the Civil War, when U.S. manufacturing was growing rapidly, tariffs were used to shield U.S. industries from foreign competition.

The introduction of the individual income tax in 1913 displaced tariffs as the main source of U.S. tax revenue. The last major U.S. tariff law was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which established an average tariff rate of 20% on all imports by 1933.

Those tariffs sparked foreign retaliation and a global trade war during the Great Depression. After World War II, the U.S. led the formation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, or GATT, which promoted tariff reduction policies as the key to economic stability and growth. As a result, global average tariff rates dropped from around 40% in 1947 to 3.5% in 2024. The U.S. average tariff rate fell to 2.5% that year, while about 60% of all U.S. imports entered duty-free.

While Congress is officially responsible for tariffs, it can delegate emergency tariff power to the president for quick action as long as constitutional boundaries are followed. The current Supreme Court case involves Trump’s use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, or IEEPA, to unilaterally change all U.S. general tariff rates and duration, country by country, by executive order. The controversy stems from the claim that Trump has overstepped his constitutional authority granted by that act, which does not mention tariffs or specifically authorize the president to impose them.

The pros and cons of tariffs

In my view, though, the bigger question is whether tariffs are good or bad policy. The disastrous experience of the tariff war during the Great Depression led to a broad global consensus favoring freer trade and lower tariffs. Research in economics and political science tends to back up this view, although tariffs have never disappeared as a policy tool, particularly for developing countries with limited sources of tax revenue and the desire to protect their fledgling industries from imports.

Yet Trump has resurrected tariffs not only as a protectionist device, but also as a source of government revenue for the world’s largest economy. In fact, Trump insists that tariffs can replace individual income taxes, a view contested by most economists.

Most of Trump’s tariffs have a protectionist purpose: to favor domestic industries by raising import prices and shifting demand to domestically produced goods. The aim is to increase domestic output and employment in tariff-protected industries, whose success is presumably more valuable to the economy than the open market allows. The success of this approach depends on labor, capital and long-term investment flowing into protected sectors in ways that improve their efficiency, growth and employment.

Critics argue that tariffs come with trade-offs: Favoring one set of industries necessarily disfavors others, and it raises prices for consumers. Manipulating prices and demand results in market inefficiency, as the U.S. economy produces more goods that are less efficiently made and fewer that are more efficiently made. In addition, U.S. tariffs have already resulted in foreign retaliatory trade actions, damaging U.S. exporters.

Trump’s tariffs also carry an uncertainty cost because he is constantly threatening, changing, canceling and reinstating them. Companies and financiers tend to invest in protected industries only if tariff levels are predictable. But Trump’s negotiating strategy has involved numerous reversals and new threats, making it difficult for investors to calculate the value of those commitments. One study estimates that such uncertainty has actually reduced U.S. investment by 4.4% in 2025.

A major, if underappreciated, cost of Trump’s tariffs is that they have violated U.S. global trade agreements and GATT rules on nondiscrimination and tariff-binding. This has made the U.S. a less reliable trading partner. The U.S. had previously championed this system, which brought stability and cooperation to global trade relations. Now that the U.S. is conducting trade policy through unilateral tariff hikes and antagonistic rhetoric, its trading partners are already beginning to look for new, more stable and growing trade relationships.

So what’s next? Trump has vowed to use other emergency tariff measures if the Supreme Court strikes down his IEEPA tariffs. So as long as Congress is unwilling to step in, it’s likely that an aggressive U.S. tariff regime will continue, regardless of the court’s judgment. That means public awareness of tariffs – and of who pays them and what they change – will remain crucial for understanding the direction of the U.S. economy.

Jim Hightower: Would Trump put a big tariff on his daughter's company?

Via OtherWords.org

Bring those jobs back home, Donald Trump bellowed to those greedy corporate executives who’ve shipped middle-class jobs out of country, or I’ll slap you with a big tariff when you try to sell your foreign-made products here.

Great stuff, Donnie — and to prove you mean business, I know just the CEO you should target first: Her name is Ivanka. Your daughter.

Her multimillion-dollar line of clothing and accessories, sold through major national retailers ranging from Macy’s to Amazon, is pitched to America’s working women. Yet practically all of her products are made on the cheap in low-wage factories in China, Indonesia and Vietnam — anywhere except America.

Imagine the message it would send to runaway corporations — and the integrity it would establish for Trump — if he slapped his first tariffs on Ivanka’s goods.

But neither Daddy Trump nor the daughter want to discuss the embarrassing conflict between his political bluster and her ethic of runaway capitalism. Instead, she’s tried to dodge the issue by saying it doesn’t matter, since she’ll “separate” herself from the business if she becomes a White House adviser.

Nice try, Ivanka, but the stench of hypocrisy will only grow nastier if you’re at your father’s side while he pretends to castigate other corporations that abscond from America.

The only way to salvage even an iota of moral virtue is to repatriate the manufacturing of your brand-name apparel. Bringing those middle-class jobs home to the Good Ol’ US of A would also make a powerful political statement.

Yet because money trumps both political savvy and the morality of simply doing what’s right, Ivanka says her corporate brand will stay offshore. As a spokeswoman put it: “We want to make responsible business decisions.”

Really? How does that “Make America Great Again”?

Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer, public speaker and editor of the newsletter, The Hightower Lowdown.