Vox clamantis in deserto

Lynn Arditi: As health-insurance costs surge, families puzzle over options

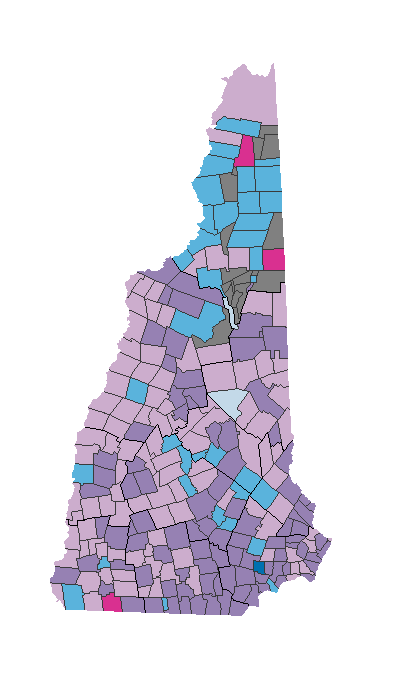

“The Sick Girl", by Michael Ancher, 1882, in National Gallery of Denmark, a nation that has very good health care.

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (except image above). This article is part of a partnership between KFF Health News and National Public Radio.

PROVIDENCE

New York-based performer Cynthia Freeman, 61, has been trying to figure out how to keep the Affordable Care Act health plan that she and her husband depend on.

“If we didn’t have health issues, I’d just go back to where I was in my 40s and not have health insurance,” she said, “but we’re not in that position now.”

Freeman and her husband, Brad Lawrence, are freelancers who work in storytelling and podcasting.

In October, Lawrence, 52, got very sick, very fast.

“I knew I was in trouble,” he said. “I went into the emergency room, and I walked over to the desk, and I said, ‘Hi, I’ve gained 25 pounds in five days and I’m having trouble breathing and my chest hurts.’ And they stopped blinking.”

Doctors diagnosed him with kidney disease, and he was hospitalized for four days.

Now Lawrence has to take medication with an average cost without insurance of $760 a month.

In January, the cost of the couple’s current “silver” plan rose nearly 75 percent, to $801 a month.

To bring in extra cash, Freeman has picked up a part-time bartending gig.

Millions of middle-class Americans who have ACA health plans are facing soaring premium payments in 2026, without help from the enhanced subsidies that Congress failed to renew. Some are contemplating big life changes to deal with new rates that kicked in on Jan. 1.

It often falls to women to figure out a family’s insurance puzzle.

Women generally use more health care than men, in part because of their need for reproductive services, according to Elizabeth Tobin-Tyler, a professor at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

Women also tend to be the medical decision-makers for the family, she said, especially for the children.

“There’s a disproportionate role that women play in families around what we think of as the mental load,” said Tobin-Tyler, and that includes “making decisions around health insurance.”

Before the holidays, Congress considered a few forms of relief for the premium hikes, but nothing has materialized, and significant deadlines have already passed.

Going Uninsured?

As the clock ticked down on 2025, B. agonized over her family’s insurance options. She was looking for a full-time job with benefits, because the premium prices she was seeing for 2026 ACA plans were alarming.

In the meantime, she decided, she and her husband would drop coverage and insure only the kids. But it would be risky.

“My husband works with major tools all day,” she said, “so it feels like rolling the dice.”

NPR and KFF Health News are identifying B. by her middle initial because she believes that her insurance needs could affect her ongoing search for a job with health benefits.

The family lives in Providence. Her husband is a self-employed woodworker, and she worked full-time as a nonprofit manager before she lost her job last spring.

After she lost her job, she turned to the ACA marketplace. The family’s “gold” plan cost them nearly $2,000 a month in premiums.

It was a lot, and they dug into retirement savings to pay for it while B. kept looking for a new position.

Because Congress failed to extend enhanced subsidies for ACA plans, despite ongoing political battles and a lengthy government shutdown over the issue, B.’s family plan would have cost even more in 2026 — almost $3,000 a month.

“I don’t have an additional $900 lying around in my family budget to pay for this,” she said.

B. had already pulled $12,000 out of retirement funds to pay her family’s 2025 rates.

Unless she finds a new job soon, the family’s projected income for 2026 will be less than 266% of the federal poverty level. That means the children qualify for free coverage through Medicaid.

So B. decided to buy a plan on the ACA marketplace for herself and her husband, paying premiums of $1,200 a month.

“The bottom line is none of this is affordable,” she said, “so we’re going to be dipping into savings to pay for this.”

Postponing a Wedding

The prospect of soaring insurance premiums put a pause on Nicole Benisch’s plans to get married.

Benisch, 45, owns a holistic wellness business in Providence. She paid $108 a month for a zero-deductible “silver” plan on Rhode Island’s insurance exchange.

But the cost in 2026 more than doubled, to $220 a month.

She and her fiance had planned to marry on Dec. 19, her late mother’s birthday. “And then,” she said, “we realized how drastically that was going to change the cost of my premium.”

As a married couple, their combined income would exceed 400% of the federal poverty level and make Benisch ineligible for financial help. Her current plan’s monthly premium payments would triple, costing her more than $700 a month.

Benisch considered a less expensive “bronze” plan, but it wouldn’t cover vocal therapy, which she needs to treat muscle tension dysphonia, a condition that can make her voice strain or give out.

If they get married, there’s another option: Switch to her fiance’s health plan in Massachusetts. But that would mean losing all her Rhode Island doctors, who would be out-of-network.

“We have some tough decisions to make,” she said, “and none of the options are really great for us.”

Lynn Arditi reports for Ocean State Media, a National Public Radio affiliate.

Charles Chieppo: Maine may be pacesetter against healthcare-price inflation

As consumers suffer sticker shock over rising-health-insurance premiums, insurers increasingly are responding with policies that aim to hold down premiums with narrower provider networks or much higher co-pays and/or deductibles.

According to the National Business Group on Health, 32 percent of American companies intended to offer only high-deductible plans to their employees last year. As out-of-pocket costs rise, so does consumer interest in the cost of the procedures they undergo.

Legislation pending in Maine would add it to the list of states requiring hospitals and other providers to share price information with prospective patients upon request. But the legislation goes further. It would make Maine the first state to let consumers and insurance companies split savings of more then $50 if the consumer can find a provider that offers the service at a cost that is lower than the regional average.

A similar shared-savings model is in place for state employees in neighboring New Hampshire. Few Maine legislators oppose price transparency, but there are concerns about the shared-savings provision.

Opponents argue that the full cost of most medical procedures is hard to determine in advance and that the financial incentives won't change consumer behavior. You are indeed unlikely to be able to get a cost estimate for a procedure as complex as openheart surgery, but one forthcoming study suggests that the savings that could be achieved from shopping around, at least for routine procedures, are far greater than expected.

The Pioneer Institute asked more than 40 hospitals in six metropolitan areas for the price of an MRI on the left knee without contrast. The prices ranged from $400 at a Los Angeles hospital to $4,544 at one in New York City. (I am affiliated with Pioneer as a senior fellow but had no involvement with the survey.)

It's hard to believe that consumers won't shop around for routine or elective procedures if they're paying a significant portion of the cost and the potential savings are that large. Indeed, the main point of the Pioneer survey is that it was very difficult for callers to get a complete price for the procedure despite state and federal health care price transparency laws.

The authors argue that it is the lack of access to price information that keeps consumers from shopping. The benefits from cost comparisons go beyond consumers' outofpocket savings.

Medical loss ratio laws require health insurers to pay out at least 80 percent of the money they receive in benefits, meaning that any savings the insurers realize from consumers shopping for lower prices will translate into premium relief.

That relief is sorely needed. The average annual premium and outofpocket costs for the nearly 60 percent of Americans covered by employer-sponsored health plans is more than $8,500. That number is expected to rise to between $13,000 and $18,000 by 2025 and could top $36,000, or about 45 percent of average household income, by 2035.

Price transparency and providing incentives for consumers to shop for better prices won't by themselves get healthcare costs under control. But faced with the prospect of families spending nearly half their income on healthcare just two decades hence, states should take action now to start bending the cost curve down. The kind of legislation that Maine is considering now could be an important first step.

Charles Chieppo (Charlie_Chieppo@hks.harvard.edu) is a research fellow at the Ash Center at Harvard's Kennedy School (and a friend of the overseer of this site). This piece originated at Web site of Governing magazine (governing.com).