Vox clamantis in deserto

Fred D. Begley: How NIH became backbone of medical research and boosted U.S. innovation and economy

Bentley University Library, in Waltham, Mass.

From The Conversation, except for image above.

Fred D. Ledley is director of the Center for Integration of Science and Industry at Bentley University.

His research has been supported by grants to Bentley University from the Institute for New Economic Thinking, National Pharmaceutical Council, West Health, and the National Biomedical Research Foundation.

(Editor’s note: There are many NIH-linked facilities in New England.)

As a young medical student in 1975, I walked into a basement lab at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., to interview for a summer job.

It turned out to be the start of a lifelong affiliation – first as a trainee, then as a grantee running a university laboratory and finally, now, as a researcher of economics and public policy studying the agency’s impact on health care and on the national economy.

On that initial visit 50 years ago, I got my first direct experience with the NIH’s mission: to tap the enormous potential of basic science to improve human health and medical care. And over the long arc of my career, I watched the agency enact this mission in ways that brought enormous value to the country. NIH funding trained a legion of biomedical scientists, produced countless therapies that underpin much of modern medicine and catalyzed the launch of the biotechnology industry.

But widespread federal grant terminations and disruptions to federal funding in 2025 have left scientists who depend on NIH support reeling. And a 40% cut to the NIH budget for 2026 proposed by the White House threatens the agency’s future.

Origins and growth of the NIH

The NIH was founded through the Ransdell Act of 1930, which converted the former Hygienic Laboratory of the Marine Hospital Services into the seeds of a new government institution. That laboratory had been established in 1887 to develop public health measures, diagnostics and vaccines for controlling diseases prevalent in the U.S. at the time, such as cholera, yellow fever, smallpox, plague and diphtheria. With the act’s passage, the Hygienic Laboratory was reimagined as the National Institute of Health.

The NIH, initially called the National Institute of Health, was created in 1930 with the passage of the Ransdell Act. President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated the new NIH campus in Bethesda, Md., on Oct. 31, 1940, saying, ‘We cannot be a strong nation unless we are a healthy nation.’ National Institutes of Health

Sen. Joseph Ransdell of Louisiana envisioned the NIH as an agency with a broader mandate for translating scientific advances to improve human health. In arguing in 1929 for the creation of the new institute, he read into the Congressional Record an editorial from The New York Times that highlighted rapid advances in chemistry, physiology and physics.

The editorial lamented that “never in the whole history of the world had efforts to improve health conditions been behind the advance in other sciences.” Pointing to millions of Americans suffering from sickness leading to economic losses “into billions,” it argued for the need for a medical sciences institute coordinating “a national effort to prevent diseases that are or may be preventable.”

In 1945, a report called Science – The Endless Frontier, by Vannevar Bush, highlighted the government’s central role in supporting science that harnessed nuclear energy, implemented radar and developed penicillin – all important elements of the United States’ success in World War II. Bush argued that these wartime successes presented a model for growing the American economy, preventing and curing disease and projecting American power.

The NIH became central to this model. Its budget increased substantially during and just after World War II, with postwar adoption of Bush’s plan, and again after 1957 when the nation redoubled its commitment to science following Russia’s launch of Sputnik and the start of the space race. The National Cancer Act of 1971, which established the separate National Cancer Institute, reaffirmed the nation’s commitment to government-funded research. This new institute’s funding provided much of the seed capital for the emergence of biotechnology.

In the 1980s, the Stevenson-Wydler and Bayh-Dole acts created a clear pathway for developing commercial products from federally funded research that would provide public benefits and economic stimulus. These federal laws made it a requirement to pursue patenting and licensing of NIH-funded research to industry.

One project’s evolution reflects NIH’s mission

Today, the NIH represents the backbone of efforts to improve health and health care, supporting each step in the process from preliminary discovery to clinical advance. These steps correspond to the stages of an individual scientist’s path.

By putting study volunteers into a specially constructed metabolic chamber, NIH researchers in the 1950s could study how the human body uses air, water and food. The nurse here is affixing a hood onto a volunteer to measure oxygen consumption. National Institutes of Health

I experienced this progression in my own career. After establishing my first independent laboratory with a grant for early-stage researchers, then called a First Independent Research Support and Transition grant, a Research Project grant, widely known as an R01, funded my lab’s work identifying genes that cause inherited metabolic diseases in newborns. R01 grants are the main mechanism that academic biomedical scientists in the U.S. rely on to support innovative research.

Later, an NIH Program Project grant enabled us to investigate how the genes we had identified could be used to treat children. A General Clinical Research Center grant supported the hospital facilities necessary for clinical research and paid for patient care. Other grants supported our medical students and fellows as they embarked on their own careers as well as applications of our research to areas such as child health, reproductive biology and gastroenterology.

As our research on gene therapy progressed, NIH Small Business grants contributed to our founding a company that raised US$200 million in investments and partnerships and created hundreds of new jobs in Houston. Grants to small businesses continue to play a crucial role in helping universities commercialize discoveries.

Is the NIH effective?

For the past decade, I have led a research center focused on characterizing the process of developing new drugs. Our work, which is not funded by the NIH, shows that an established foundation of basic research on the biology underlying health and disease is necessary for successful drug development – and that most of this research is performed in public institutions.

We have found that NIH funding supported basic or applied research related to about 99% of newly approved medicines, clinical trials for 62% of these drugs and patents governing about 10% of these products.

Based on research conducted at the NIH, azidothymidine, or AZT, in 1987 became the first drug approved to treat AIDS. Here, the drug, added to the middle vial, protects healthy immune cells from being destroyed by HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. John Crawford, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health

Studies also show that this NIH funding saves industry almost $3 billion per drug in development costs. Over the past decade, there has been $800 billion in new investment in biotechnology. The U.S. biopharmaceutical industry directly supports more than 1 million jobs.

Medicines enabled by NIH funding have been crucial for increasing life expectancy and health – dramatically decreasing deaths due to heart disease and stroke, improving cancer outcomes, controlling HIV infection, improving the management of immunological diseases and easing the burden of psychiatric conditions.

The Trump administration is currently questioning the role of science in maintaining the nation’s health, economy and global posture. Yet the NIH stands as a testimony to the vision articulated by its early architects.

At its heart is the conviction that science is good for society, that persistent investment in basic research is essential to technological advances that serve the public interest, and that our nation’s health and economy benefit from developments in biology.

Llewellyn King: ‘Long COVID’s’ baffling sister

CFS vitim demonstrates for more research

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Long COVID’’ is the condition wherein people continue to experience symptoms for longer than usual after initially contracting COVID-19. Those symptoms are similar to the ones of another long-haul disease, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, often called Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

For a decade, in broadcasts and newspaper columns, I have been detailing the agony of those who suffer from ME/CFS. My word hopper isn’t filled with enough words to describe the abiding awfulness of this disease.

There are many sufferers, but how ME/CFS is contracted isn’t well understood. Over the years, research has been patchy. However, investigation at the National Institutes of Health has picked up and the disease now has measurable funding -- and it is taken seriously in a way it never was earlier. In fact, it has been identified since 1955, when the Royal Free Hospital, in London, had a major outbreak. The disease had certainly been around much longer.

In the mid-1980’s, there were two big cluster outbreaks in the United States -- one at Incline Village, on Lake Tahoe in Nevada, and the other in Lyndonville in northern New York. These led the Centers for Disease Control to name the disease “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.”

The difficulty with ME/CFS is there are no biological markers. You can’t pop round to your local doctor and leave some blood and urine and, bingo! Bodily fluids yield no clues. That is why Harvard Medical School researcher Michael VanElzakker says the answer must lie in tissue.

ME/CFS patients suffer from exercise, noise and light intolerance, unrefreshing sleep, aching joints, brain fog and a variety of other awful symptoms. Many are bedridden for days, weeks, months and years.

In California, I visited a young man who had to leave college and was bedridden at his parents’ home. He couldn’t bear to be touched and communicated through sensors attached to his fingers.

In Maryland, I visited a teenage girl at her parents’ home. She had to wear sunglasses indoors and had to be propped up in a wheelchair during the brief time she could get out of bed each day.

In Rhode Island, I visited a young woman, who had a thriving career and social life in Texas, but now keeps company with her dogs at her parents’ home because she isn’t well enough to go out.

A friend in New York City weighs whether to go out to dinner (pre-pandemic) knowing that the exertion may cost her two days in bed.

I know a young man in Atlanta who can work, but he must take a cocktail of 20 pills to deal with his day.

Some ME/CFS sufferers get somewhat better. The instances of cure are few; of suicide, many.

Onset is often after exercise, and the first indications can be flu-like. Gradually, the horror of permanent, painful, lonely separation from the rest of the world dawns. Those without money or family support are in the most perilous condition.

Private groups -- among them the Open Medicine Foundation, the Solve ME/CFS Initiative, and ME Action -- have worked tirelessly to raise money and stimulate research. The debt owned them for their caring is immense. This has allowed dedicated researchers from Boston to Miami and from Los Angeles to Ontario to stay on the job when the government has been missing. Compared to other diseases, research on ME/CFS has been hugely underfunded.

Oved Amitay, chief executive officer of the Solve ME/CFS Initiative, says Long COVID gives researchers an opportunity to track the condition from onset and, importantly, to study its impact on the immune system – known to be compromised in ME/CFS. He is excited.

In December, Congress provided $1.5 billion in funding over four years for the NIH to support research into Long COVID. The ME/CFS research community is glad and somewhat anxious. I’m glad that there will be more money for research, which will spill into ME/CFS, and worried that years of endeavor, hard lessons learned and slow but hopeful progress will be washed away in a political roadshow full of flash.

Ever since I began following ME/CFS, people have stressed to me that more money is essential. But so are talented individuals and ideas.

Long COVID needs carefully thought-out proposals. If it is, in fact, a form of ME/CFS, it is a long sentence for innocent victims. I have received many emails from ME/CFS patients who pray nightly not to wake up in the morning. The disease is that awful.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

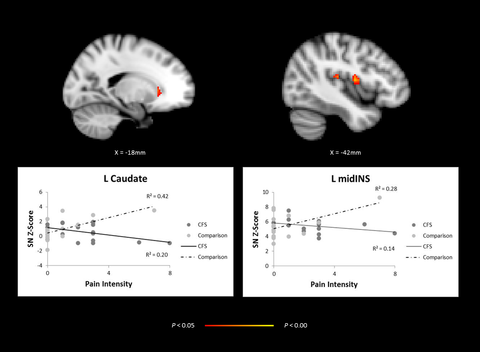

Brain imagining, comparing adolescents with CFS and healthy controls showing abnormal network activity in regions of the brain

Llewellyn King: The U.S. cancer-research crisis

By LLEWELLYN KING

No diagnosis strikes fear into people as thoroughly as cancer. It is the sum of all fears when it comes to health.

My mother died in 1961, when treatments were few, in great pain from cancer of the uterus. Four treasured friends died of cancer more recently, but in equally awful ways; Barbara of bone cancer, Grant of colon cancer, Ian of brain cancer, and JoAnn of melanoma.

Cancer deserves its position as the most feared disease, even if it is not as lethal as it once was and many cancers can be treated. To know someone in the throes of cancer is to know something terrible. Heart disease kills more of us, but cancer is enthroned as the ultimate horror.

Yet we are, in some measure, winning the war on cancer; to medical science, it is less mysterious and more conquerable. But it has been a long battle against an implacable enemy.

The war on cancer is war with many theaters; cancer itself being a misnomer, as there are many cancers with very different profiles, rates metastasis and treatments.

So it is both puzzling and appalling that Congress has allowed funding for government biomedical research to languish and has made it subject to the blunt tool of sequestration. Less money means everything slows down; research projects are drawn out or cancelled, and scientists are discouraged.

Nothing is as fatal for research as uncertain funding. You cannot shut down a line of research and start it up again as funds become available: It blunts the picks.

Scientists at the hard-rock face of research cannot be expected to sustain commitment when they do not know if their research grants will be renewed in the next budget cycle. Lawyers can anticipate steady work, why not can cancer researchers? When we implore young people to study biomedicine, we are asking them to take up a career of uncertainty.

Enter the non-government funders, from giants like the American Cancer Society to small but determined outfits like the National Foundation for Cancer Research (NFCR).

This organization, according to its president, Franklin Salisbury Jr., believes in “adventure funding.” Although he eschews the description, Salisbury’s efforts might be called seed funding at the genomic and molecular level; understanding the role of genes in cancers and finding the mechanisms that control cells. He emphasizes the gap between science and medicine, and the need to provide funding to bridge that gap.

Salisbury also underscores the need for regular funding, rather than large periodic and unpredictable infusions. His organization, founded in 1973 by his father, Franklin Sr., a creative entrepreneur, and Albert Szent-Györgyi, a Hungarian-born physiologist and biochemist who won the Nobel Prize 1937, has been keeping research alive for some researchers, such as Dr. Curt Civin, of the University of Maryland Medical Center, and Dr. Harold Dvorak, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, in Boston.

NFCR is just one — and a small one, with a $15 million annual budget — of hundreds of cancer-related charities. Its uniqueness and what it portends for the whole future of research is its willing support, within the research community, of disruptive biomedical technologies as well as its appreciation for long-term support for particular scientists. These scientists are part of establishment teaching hospitals like Massachusetts General, as well as an honors list of top universities from Harvard to Oxford and across the Pacific to China.

Increasingly, China is becoming more important in biomedical research. American dollars are finding their way into Chinese research Institutions, as a new wave of collaboration outside of traditional channels is being established. These are sometimes housed in open medicine centers, six of which NFCR supports.

With the pressure here on government funding, researchers fear the government will fund only the safe and sure projects. This is being felt across the broad range of biomedical research in the, as scientists are turned away in larger and larger numbers from the National Institutes of Health empty handed. Respected researchers are turning to innovative funding sources, including crowd-sourcing. A renowned virus researcher at Columbia, Dr. Ian Lipkin, is trying to raise $1.27 million, having been turned down by NIH, by crowdsourcing

Llewellyn King is a national columnist and a longtime publisher, and the co-host of White House Chronicle, which appears on many PBS stations.