Michael J. Socolow: Will networks let autocratic Trump become their editor?

Michael J. Socolow is a professor of communication and journalism at the University of Maine.

His father, Sanford Socolow, worked for CBS News from 1956 to 1988.

ORONO, Maine

It was a surrender widely foreseen. For months, rumors abounded that Paramount would eventually settle the seemingly frivolous lawsuit brought by President Trump concerning editorial decisions in the production of a CBS interview with Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris in 2024.

On July 2, 2025, those rumors proved true: The settlement between Paramount and Trump’s legal team resulted in CBS’s parent company agreeing to pay $16 million to the future Donald Trump Library – the $16 million included Trump’s legal fees – in exchange for ending the lawsuit. Despite the opinion of many media law scholars and practicing attorneys who considered the lawsuit meritless, Shari Redstone, the largest shareholder of Paramount, yielded to Trump.

Redstone had been trying to sell Paramount to Skydance Media since July 2024, but the transaction was delayed by issues involving government approval.

Specifically, when the second Trump administration assumed power, on Jan. 20 2025, the new Federal Communications Commission had no legal obligation to facilitate, without scrutiny, the transfer of the CBS network’s broadcast licenses for its owned-and-operated TV stations to new ownership.

The FCC, under newly installed Republican Chairman Brendan Carr, was fully aware of the issues in the legal conflict between Trump and CBS at the time Paramount needed FCC approval for the license transfers. Without a settlement, the Paramount-Skydance deal remained in jeopardy.

Until it wasn’t.

At that point, Paramount joined Disney in implicitly apologizing for journalism produced by their TV news divisions.

Earlier in 2025, Disney had settled a different Trump lawsuit with ABC News in exchange for a $15 million donation to the future Trump Library. That lawsuit involved a dispute over the wording of the actions for which Trump was found liable in a civil lawsuit brought by E. Jean Carroll.

GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump said the CBS interview with Democratic nominee Kamala Harris was ‘‘fraudulent interference with an election.’’

It’s not certain what the ABC and CBS settlements portend, but many are predicting they will produce a “chilling effect” within the network news divisions. Such an outcome would arise from fear of new litigation, and it would install a form of internal self-censorship that would influence network journalists when deciding whether the pursuit of investigative stories involving the Trump administration would be worth the risk.

Trump has apparently succeeded where earlier presidents failed.

Presidential pressure

From Jimmy Carter trying to get CBS anchor Walter Cronkite to stop ending his evening newscasts with the number of days American hostages were being held in Iran to Richard Nixon’s administration threatening the broadcast licenses of The Washington Post’s TV stations to weaken Watergate reporting, previous presidents sought to apply editorial pressure on broadcast journalists.

But in the cases of Carter and Nixon, it didn’t work. The broadcast networks’ focus on both Watergate and the Iran hostage crisis remained unrelenting.

Nor were Nixon and Carter the first presidents seeking to influence, and possibly control, network news.

President Lyndon Johnson, who owned local TV and radio stations in Austin, Texas, regularly complained to his old friend, CBS President Frank Stanton, about what he perceived as biased TV coverage. Johnson was so furious with the CBS and NBC reporting from Vietnam, he once argued that their newscasts seemed “controlled by the Vietcong.”

Yet none of these earlier presidents won millions from the corporations that aired ethical news reporting in the public interest.

Before Trump, these conflicts mostly occurred backstage and informally, allowing the broadcasters to sidestep the damage to their credibility should any surrender to White House administrations be made public. In a “Reporter’s Notebook” on the CBS Evening News the night of the Trump settlement, anchor John Dickerson summarized the new dilemma succinctly: “Can you hold power to account when you’ve paid it millions? Can an audience trust you when it thinks you’ve traded away that trust?”

“The audience will decide that,” Dickerson continued, concluding: “Our job is to show up to honor what we witness on behalf of the people we witness it for.”

During the Iran hostage crisis, CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite ended every broadcast with the number of days the hostages had been held captive.

Holding power to account

There’s an adage in TV news: “You’re only as good as your last show.”

Soon, Skydance Media will assume control over the Paramount properties, and the new CBS will be on the airwaves.

When the licenses for KCBS in Los Angeles, WCBS in New York and the other CBS-owned-and-operated stations are transferred, we’ll learn the long-term legacy of corporate capitulation. But for now, it remains too early to judge tomorrow’s newscasts.

As a scholar of broadcast journalism and a former broadcast journalist, I recommend evaluating programs like 60 Minutes and the CBS Evening News on the record they will compile over the next three years – and the record they compiled over the past 50. The same goes for ABC World News Tonight and other ABC News programs.

A major complicating factor for the Paramount-Skydance deal was the fact that 60 Minutes has, over the past six months, broken major scoops embarrassing to the Trump administration, which led to additional scrutiny by its corporate ownership. Judged by its reporting in the first half of 2025, 60 Minutes has upheld its record of critical and independent reporting in the public interest.

If audience members want to see ethical, independent and professional broadcast journalism that holds power to account, then it’s the audience’s responsibility to tune it in. The only way to learn the consequences of these settlements is by watching future programming rather than dismissing it beforehand.

The journalists working at ABC News and CBS News understand the legacy of their organizations, and they are also aware of how their owners have cast suspicion on the news divisions’ professionalism and credibility. As Dickerson asserted, they plan to “show up” regardless of the stain, and I’d bet they’re more motivated to redeem their reputations than we expect.

I don’t think that reporters, editors and producers plan to let Donald Trump become their editor-in-chief over the next three years. But we’ll only know by watching.

Hilary Cosell: My father's friendship with Muhammad Ali and their fight for justice

“I’m gonna kill you, nigger-loving Jew bastard.”

The so-called Jew bastard was my late father, the broadcast sports journalist Howard Cosell, and the quote typical of the hate mail that poured into his office from the moment in 1964 that he said, “If your name is Muhammad Ali, I will call you Muhammad Ali.”

Muhammad’s death on June 3 was a bit like my father dying a second time, because as long as Ali was alive, a piece of my father still lived. Together they represented the very best that this country has to offer, and exposed the worst, too.

As the Ali accolades poured in, and his status as a national treasure remained firmly in place, as I watched and listened to the round-the-clock tributes, I thought back to those years between 1964 and 1971, during which Ali was stripped of his title, the years he lost in boxing, and the hatred that engulfed him. I wondered how many people lauding him now even remember those days, or the true reasons why he deserved such praise.

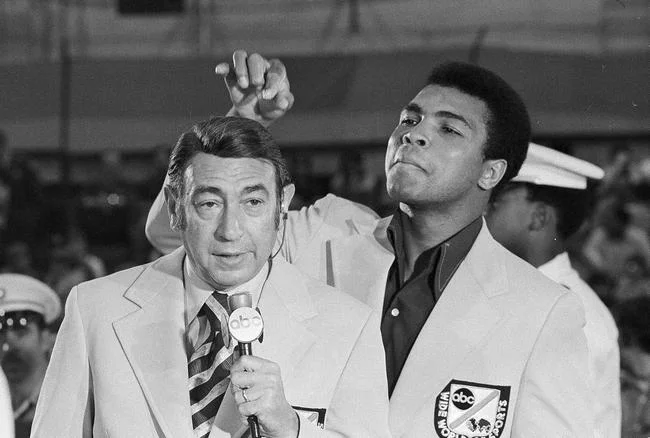

My dad covered boxing for ABC, and so he began to cover Ali. Right from the start they had the kind of rapport that often develops between two smart, fast-talking people. On camera together their relationship was entertaining, and they became synonymous in people’s minds: Ali-Cosell, Cosell-Ali.

But there was a bond between them that had nothing to do with repartee. It was forged during those years of the Freedom Summer, of riots and cities burning in the summer of 1965, the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, the draft, and the Vietnam War, and the Black Power Movement.

My father stood alone and stood his ground when he used Muhammad’s name. Sportswriters and broadcasters refused to speak it, and The New York Times wouldn’t print it. Other boxers continued to use it, and paid for it in the ring.

In 1966 Ali was reclassified as 1A by his draft board, and in 1967 he refused to step forward, and applied for conscientious objector status on religious grounds.

He was stripped of his title, stripped of the right to box professionally, his passport was lifted, and many Americans despised him.

He was called an ingrate, a coward, uppity, someone who didn’t know his place, a traitor, and accused of treason. What made his decision even worse, if possible, was the that he had joined a separatist black Muslim “nation” founded by Malcolm X. (He later left it and practiced a different form of Islam.) It’s no exaggeration to say that he was white America’s nightmare: a young, strong, articulate, separatist black man who said, “No Vietcong ever called me nigger.”

Alone again, my father rose to Ali’s defense. Howard Cosell was a lawyer and knew what was at stake immediately. This had nothing to do with boxing. At issue were freedom of speech, freedom of religion, equal protection and due process.

Amidst the hysteria and hate, my father explained the law, and Ali’s rights, over and over again. Few listened.

When Ali couldn’t box, my dad periodically interviewed him on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, and used him as a commentator on fights. He kept his name, face and case before the public.

One of my favorite stories about them took place at a classic, elegant New York restaurant, called Café des Artistes. It was a hangout for ABC, because the network’s headquarters was directly across the street.

It was a Saturday, lunchtime, and my mother and I got a table and ordered lunch, while my father did an interview with Ali. Suddenly there was a commotion at the entrance and my father strolled in with Ali and his entourage.

“Look who I brought to see you, Em,” he said to my mother, Emmy.

The maître d’ was used to my dad showing up with unexpected people. Tables were quickly pushed together, and Muhammad and friends sat down to eat. I looked around the restaurant, which was fairly crowded with a lily-white clientele who fell silent when Ali arrived, and simply stared. We ignored them.

After they had eaten and left, an older white gentleman cautiously approached our table and asked if he could speak with my father. He nodded.

“Why did you bring him here, Mr. Cosell? He doesn’t belong here. We’re afraid of him. Aren’t you?”

My father looked at the man and quietly replied, “With all due respect, sir, the only thing I’m afraid of are the sentiments you just expressed.” My father then said, “If you’ll excuse me, I’m lunching with my family.” The man scurried away.

Some revisionist historians write that Muhammad and my father were never friends, and that my father hooked on to Ali to further his career, not out of any sense of justice. It’s true that they helped each other’s careers along the way. But Howard Cosell’s defense of Ali defined my father’s career, as well as his character, conscience and courage -- and defined a bond of trust between two unlikely men that would never be broken.

Hilary Cosell is a Connecticut-based writer anda former NBC sports journalist and an occasional contributor to New England Diary.