The holidays in Boston through the centuries

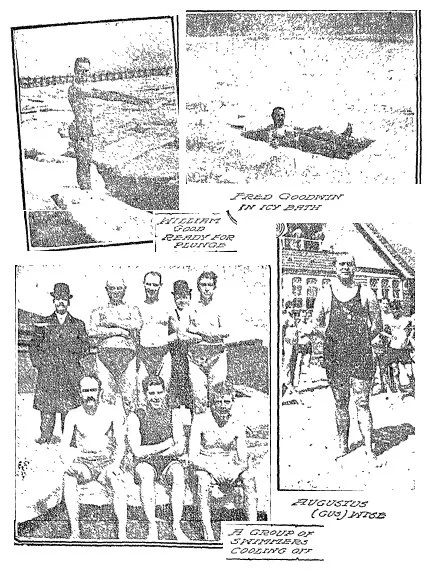

Photo montage of the L Street (in South Boston) Brownies published in The Boston Globe in 1913 under “Swimming Races for Brownies' Christmas Day"

From The Boston Guardian (except for image above):

(New England Diary’s editor/publisher, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Guardian.

On Jan. 1, 1701, Samuel Sewall, a prominent Boston jurist and Beacon Hill resident, distributed an ode to the new year and sent trumpeters to the Boston Common to herald the arrival of the hours-old 18 th Century.

Though festivities were often muted in colonial times, New Year’s 2021 will continue the celebration of a holiday that has been commemorated in Boston for hundreds of years.

In 17th Century New England, Christmas traditions were frowned upon, which caused some Bostonians to restrain their celebration until the new year.

Although Massachusetts operated on the Julian calendar, which put New Year’s on March 25th, many residents still commemorated the holiday on Jan. 1.

“It was illegal to celebrate Christmas during the Puritan ascendancy,” Peter Drummey, the Massachusetts Historical Society’s librarian, told The Guardian. “In some respects, they had New Year’s in lieu of the Christmas holidays.”

Still, New Year’s celebrations were minor in the colonies until the 19th Century, when droves of new immigrants arrived on American shores. Scots Irish newcomers brought with them a poem by Robert Burns called “Auld Lang Syne,’’ which they sang as the clock struck midnight on Dec. 31.

In 1863, amidst the devastation of the Civil War, thousands filled the Boston Music Hall and Tremont Temple to await the news from Washington, where President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which would free enslaved people living in Confederate states, was scheduled to go into effect.

Abolitionists such as Frederick Douglas and William Lloyd Garrison attended musical performances while a string of citizens stood between the concert halls and the telegraph office, ready to conduct the announcement to the anxious crowds.

“People who were ardent in the abolitionist cause had to see the news to really believe that it had happened; they had to have the proof,” Drummey said. “This was the only time that Boston had historically celebrated on a scale that we associate with New Year’s [today], but for reasons completely apart from the holiday.”

In the following decades, immigrants continued to arrive and change the annual traditions. Many were fleeing famine, revolution, or persecution.

“These people were bringing new traditions, new thoughts, and new beliefs,” Anthony Sammarco, a Boston historian, told The Guardian. “[Many] were looking to the new year to be better than the old one.”

In the 20th Century, other traditions developed, such as the annual polar plunge in Dorchester and ice skating at the Frog Pond. Immigrants from Latin American countries brought the practice of eating a dozen grapes at midnight. In 1976, artist Clara Mack Wainwright reinvigorated the city’s holiday by establishing First Night, a celebration that gathered musicians, artists, and revelers.

“Parkas and hiking boots on the Common…rocking saxophones in the frigid night air, thrumming guitars in the warmth of a Catholic church, champagne on Beacon Street, beer at Park Street Station, and vice versa,” reported The Boston Globe the following day. First Night grew each year, and by 1990 over a million people were attending the celebration, according to The Globe.