Vox clamantis in deserto

‘The weight of displacement’

“Kathe’s Blues” (photo transfer on patinaed metal), by Lisa Cohen, in her show “Beneath the Layers,’’ at the Wellfleet (Mass.) Preservation Hall, through Aug. 31.

The curator explains that the show is “a deeply personal and evocative look at the journey and challenges faced by immigrant families through the artists’s family experience fleeing Europe in World War II. Lisa Cohen captures the emotional weight of displacement, the resilience of the human spirit, and the enduring power of family bonds through her artwork.’’

Sonali Kolhatkar: Fatal Fall River fire displayed the assisted-living crisis

Gabriel House before the fire.

Via OtherWords.org

A deadly fire at Gabriel House, an assisted living facility in Fall River, Mass., claimed 10 lives on July 13-14.

In the aftermath, horrific scenes emerged of elderly residents trapped inside smoke-filled rooms and hanging out of windows, desperate for rescue. Victims ranged in age from 61 to 86.

Over the years, Gabriel House owner Dennis Etzkorn has faced several charges over sexual harassment and kickbacks, but was not indicted. Regulators cited the facility for violations around staffing and emergency preparedness but never followed up. Former staffer Debbie Johnson told CBS Boston that the facility was “horrible,” dirty and understaffed.

Etzkorn reportedly owns several care facilities for elders in Massachusetts. This sort of consolidation in ownership of assisted living and other senior-centered facilities is increasingly common across the country.

And that, says author Judy Karofsky, is a serious problem — even when the owners are nonprofit corporations. “There really is no difference in the performance [whether they are nonprofit or for-profit],” Karofsky told me.

Her book, DisElderly Conduct: The Flawed Business of Assisted Living and Hospice explores her personal experience navigating the system to care for her mother. “My mother was injured, my mother was sexually assaulted. My mother had many, many falls because there just wasn’t enough staffing,” said Karofsky.

The assisted-living industry relies heavily on immigrant laborers who are overworked and underpaid. According to Karofsky, “We need to honor them, understand who they are, what they’re willing to do.”

Karofsky’s mother loved many of the people who cared for her, but “some of them …were so unhappy or frustrated in their situation, they really couldn’t give the kind of care that she needed.” Many held multiple jobs, moved from one facility to another, and were offered only temporary positions.

The crisis of care in assisted living boils down to funding — or lack thereof.

Because these are a relatively new sort of institution — different from nursing homes or hospice care facilities — assisted living facilities are ruthlessly frugal and notorious for cutting corners. There’s little federal regulation, and not enough funding for staff training or the sort of memory care that elderly people increasingly need.

“Yes, we are living longer — good for us,” said Karofsky. “Now we have an obligation to provide health facilities, care facilities till the end of our days and not cut back on the sources of funds that would ease our passage.”

There’s a powerful analogy with child care. Most parents rely on the childcare industry, and yet it’s increasingly unaffordable, even though most childcare workers are underpaid. Yet the well-being of children is at stake.

“It’s profiteering. It’s exploitation,” said Karofsky of the assisted living industry, whose facilities are growing more expensive each year even as workers struggle for fair pay.

How is it that industries like these are simultaneously in high demand, exploitative to workers, and unaffordable?

It takes an enormous amount of work for humans to take care of other humans. That’s one of the best reasons for public taxation — to consolidate resources so we can pay people like us fair wages to care for people like us.

Instead of using our tax dollars for things like elder care (and child care), politicians are increasingly cutting funds from programs like Medicaid, as President Donald Trump and the GOP’s so-called “Big, Beautiful Bill” recently did.

Wealthy elders will get the luxury care they need. The rest of us — if we’re lucky enough to live into our 70s and 80s — may find ourselves living in assisted living facilities in our golden years.

Don’t we deserve well-regulated, well-funded institutions where we can enjoy independence, safety, and robust care — rather than abuse, accidents, and tragic deaths like the ones at Gabriel House?

“We need to be more concerned about our elders,” said Karofsky. “We can offer better care and more… compassionate care.”

Sonali Kolhatkar is an OtherWords.org columnist.

Our little lives

“A Rising Tide Lifts All...’’ (encaustic) by Providence-based painter Nancy Whitcomb.

‘Between forged and found’

“Garganta Cueva,’’ by Estefania Puerta, in her show at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Greenwich, Conn., Sept. 18-Jan. 11.

The museum says:

“‘Estefania Puerta’ marks the artist’s first solo museum presentation, featuring two new wall reliefs alongside ‘Garganta Cueva’ (2023). Born in Manizales, Colombia, Puerta immigrated to the United States at age two, settling with her family in East Boston. Drawing from her experience growing up undocumented, her work recasts the terms of categorization—blurring the lines between what is forged and found, felt and repressed, spoken and withheld. Influenced by literature, mythology, and psychoanalysis, she delves into themes of shapeshifting and transformation, reflecting on what is gained or lost through cultural and material translation.’’

The key ecological role of bats in New England

A Big Brown Bat Big (species found in New England) in flight.

— Photo by Rhododendrites

From an article by Frank Carini in ecoRI News’s series Wild New England, except for picture above.

“Across North America dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and other pesticides had a significant impact on bats from the 1940s through the ’60s. Since the ban of DDT, in 1972, bat populations had been slowly recovering, until a fungal disease appeared three-plus decades later.

“Bat populations crashed again, when white-nose syndrome was discovered in a New York cave in 2006. The fungus that causes the disease spread rapidly across much of the United States, and the number of bat species that hibernate in caves and mines plummeted….

{But bats seem to be overcoming their latest challenges.}

‘‘These mammals play a vital ecosystem role. The nine bat species found in southern New England are insectivores, meaning they eat insects such as mosquitoes and some moths humans would label pests. It’s been estimated that an individual bat can eat 600 insects an hour. Nearly 70% of bat species feed primarily on insects. Some eat fruit, rodents, frogs, and fish….’’

Llewellyn King: Sorry, Trump, solar and wind power will keep growing in U.S.; utilities urgently need them

BlueWave's 5.74 MW DC, 4 MW community solar project in Orrington, Maine. It’s one of the largest such facilities in New England.

—Courtesy: BlueWave

The small wind farm off Block Island.

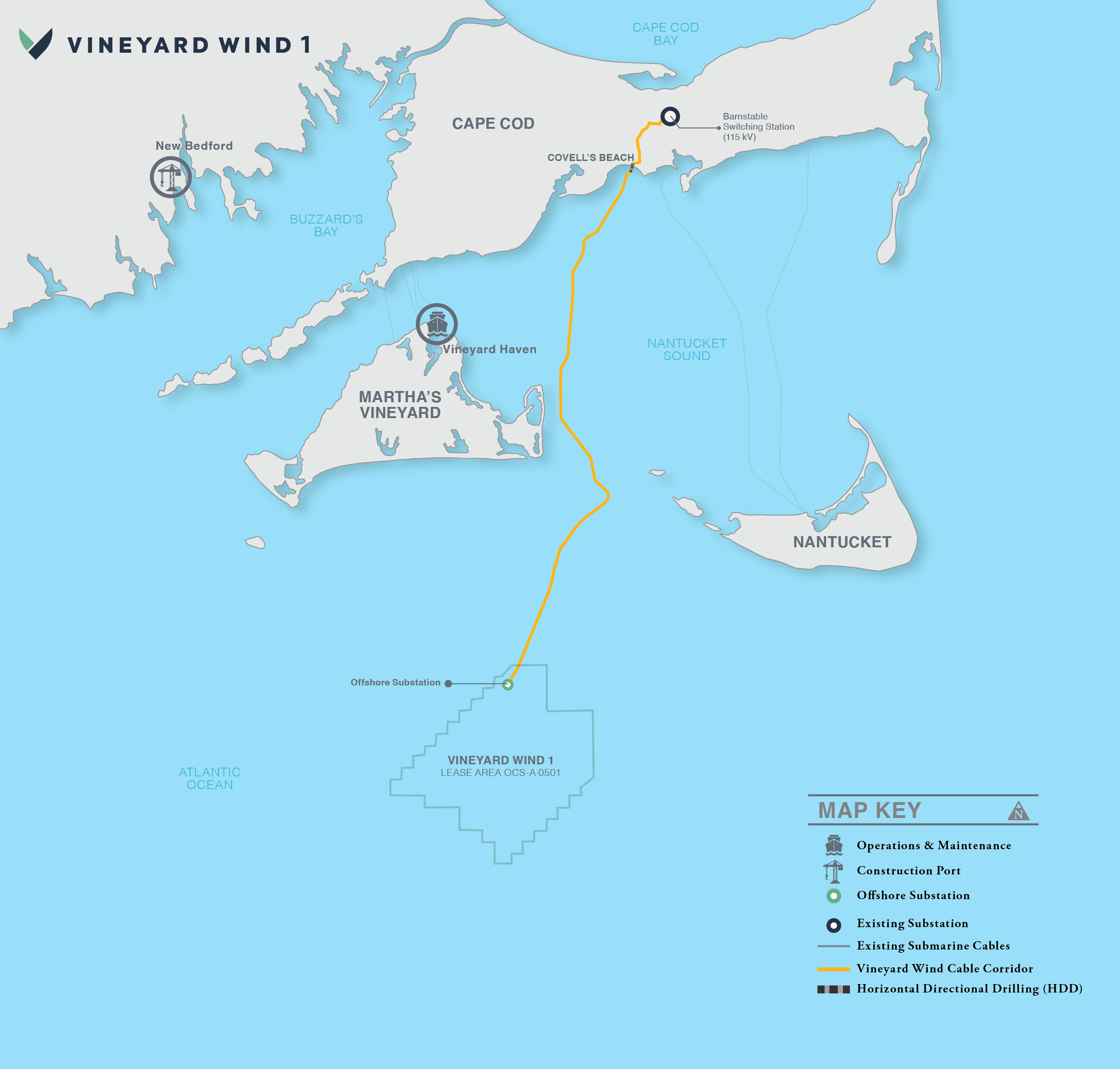

Vineyard Wind 1 is partly operating.

This commentary was originally published in Forbes.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

President Trump reiterated his hostility to wind generation when he recently arrived in Scotland for what was ostensibly a private visit. “Stop the windmills,” he said.

But the world isn’t stopping its windmill development and neither is the United States, although it has become more difficult and has put U.S. electric utilities in an awkward position: It is a love that dare not speak its name, one might say.

Utilities love that wind and solar can provide inexpensive electricity, offsetting the high expense of battery storage.

It is believed that Trump’s well-documented animus to wind turbines is rooted in his golf resort in Balmedie, near Aberdeen, Scotland. In 2013, Trump attempted to prevent the construction of a small offshore wind farm — just 11 turbines — roughly 2.2 miles from his Trump International Golf Links, but was ultimately unsuccessful. He argued that the wind farm would spoil views from his golf course and hurt tourism in the area.

Trump seemingly didn’t just take against the local authorities, but against wind in general and offshore wind in particular.

Yet fair winds are blowing in the world for renewables.

Francesco La Camera, director general of the International Renewable Energy Agency, an official United Nations observer, told me that in 2024, an astounding 92 percent of new global generation was from wind and solar, with solar leading wind in new generation. We spoke recently when La Camera was in New York.

My informal survey of U.S. utilities reveals they are pleased with the Trump administration’s efforts to simplify licensing and its push to natural gas, but they are also keen advocates of wind and solar.

Simply, wind is cheap and as battery storage improves, so does its usefulness. Likewise, solar. However, without the tax advantages that were in President Joe Biden’s signature climate bill, the Inflation Reduction Act, the numbers will change, but not enough to rule out renewables, the utilities tell me.

China leads the world in installed wind capacity of 561 gigawatts, followed by the United States with less than half that at 154 GW. The same goes for solar installations: China had 887 GW of solar capacity in 2024 and the United States had 239 GW.

China is also the largest manufacturer of electric vehicles. This gives it market advantage globally and environmental bragging rights, even though it is still building coal-fired plants.

While utilities applaud Trump’s easing of restrictions, which might speed the use of fossil fuels, they aren’t enthusiastic about installing new coal plants or encouraging new coal mines to open. Both, they believe, would become stranded assets.

Utilities and their trade associations have been slow to criticize the administration’s hostility to wind and solar, but they have been publicly cheering gas turbines.

However, gas isn’t an immediate solution to the urgent need for more power: There is a global shortage of gas turbines with waiting lists of five years and longer. So no matter how favorably utilities look on gas, new turbines, unless they are already on hand or have set delivery dates, may not arrive for many years.

Another problem for utilities is those states that have scheduled phasing out fossil fuels in a given number of years. That issue – a clash between federal policy and state law — hasn’t been settled.

In this environment, utilities are either biding their time or cautiously seeking alternatives.

For example, facing a virtual ban on new offshore wind farms, veteran journalist Robert Whitcomb wrote in his New England Diary that the New England utilities are looking to wind power from Canada, delivered by undersea cable. Whitcomb co-wrote (with Wendy Williams) a book, Cape Wind: Money, Celebrity, Energy, Class, Politics and the Battle for Our Energy Future, about offshore wind, published in 2007.

New England is starved of gas as there isn’t enough pipeline capacity to bring in more, so even if gas turbines were readily available, they wouldn’t be an option. New pipelines take financing, licensing in many jurisdictions, and face public hostility.

Emily Fisher, a former general counsel for the Edison Electric Institute, told me, “Five years is just a blink of an eye in utility planning.”

On July 7, Trump signed an executive order which states: “For too long the Federal Government has forced American taxpayers to subsidize expensive and unreliable sources like wind and solar.

“The proliferation of these projects displaces affordable, reliable, dispatchable domestic energy resources, compromises our electric grid, and denigrates the beauty of our Nation’s natural landscape.”

The U.S. Energy Information Administration puts electricity consumption growth at 2 percent nationwide. In parts of the nation, as in some Texas cities, it is 3 percent.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island

In The Green Mountain State’s short swimming season

“Couple on Bridge” (watercolor), by William Talmadge Hall, in his “Obstruction to a Landscape” series. He grew up in Vermont and Rhode Island.

Using beach debris to make some statements

“Five Articles Selected for the Poly S. Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum” (painted salvaged plastic, ink, wax), in the show “Duke Riley: What the Waves May Bring,’’ at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass., through Sept. 14.

The museum says Mr. Riley “transforms salvaged plastic collected from beaches and waterways into intricate mosaics and sculptures inspired by maritime history and folk traditions. The exhibition features finely crafted artworks that reference 19th Century nautical history and maritime crafts — such as scrimshaw, fishing lures, and sailors’ valentines—yet are made from contemporary debris. Through these unexpected materials, Riley offers a striking commentary on corporate greed, ocean degradation, and the stories we choose to preserve.’’

Chris Powell: Why Trump is squeezing Yale, et al.

In simpler times: Front view of “Yale-College" and the chapel, printed by Daniel Bowen in 1786.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

For many years the ravenous far left in Connecticut has advocated taxing Yale University, in New Haven. Yale's endowment long has been managed spectacularly well and now totals more than $40 billion, the second-largest university endowment in the country, trailing only Harvard's.

Indeed, the popular joke is that Yale is a hedge fund masquerading as a university. The popular resentment is that about 57 percent of real estate in New Haven is exempt from municipal property taxes and most of that exempt property, worth about $3.5 billion, is owned by Yale.

Financial aid from state government and “payments in lieu of taxes" makes up for some of the foregone property-tax revenue but far from all of it. Of course, if Yale's property was fully subject to the city's property tax, the city wouldn't be any better off, given its awful management, but city employees might be able to retire at full pay after only two or three years on the job, since the satisfaction of its employees is city government's highest objective.

Now reform is coming to Yale not because of leftists in Connecticut but, ironically, because of President Trump and the narrow Republican majority in Congress.

Their new federal tax and spending law imposes progressive taxes on college endowments. The biggest endowments, like Yale's, will be taxed at 4 percent a year, and one study estimates that this will clip Yale's for $1.5 billion over five years.

Of course Trump and the Republicans aren't taxing college endowments out of any liberal belief in wealth redistribution. They are taxing the endowments because higher education has become a great engine of the political left and the Democratic Party, which is also why Connecticut state government, a leftist Democratic operation, has declined to tax the endowments of private colleges (Yale's particularly) and has declined to subject private colleges (again, Yale particularly) to municipal property taxes.

The Republicans want to cut higher education down to size politically while the Democrats want to keep it a strong source of patronage and propaganda.

Trump and the Republicans are right for the wrong reasons, but that's better than being wrong. For as the college loan disaster has shown, higher education's importance to the country is grossly overestimated. The country's education problem is lower education, as shown by the few proficiency tests still permitted in elementary, middle, and high schools in Connecticut, and by their disgraceful racial performance gaps.

COWARDLY, UNACCOUNTABLE, PATHETIC: How much more does anyone really need to know about the corruption and incompetence of the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities System than something that was reported a week ago?

The system is still embroiled in the scandal over its departing chancellor, Terrence Cheng, who last year was caught abusing his expense account despite his annual compensation of nearly $500,000. The system's Board of Regents decided he had to go but feared that the contract the board had given him, which extended to next July, might be construed in court to prevent his dismissal. So it was agreed that he would leave the chancellorship on July 1 and become "strategic adviser" to the board for another year, doing amorphous stuff for the same compensation.

An interim chancellor, O. John Maduko, lately administrator of the community college system, has been appointed to serve for a year at a salary estimated at $425,000, not counting fringe benefits.

Fair questions remain about the college system's administration and state legislators continue to criticize it. So a week ago, the Hartford Courant asked for an interview with the chairman of the Board of Regents, Martin Guay. He refused.

How cowardly, unaccountable, and pathetic for the chairman of a major government agency.

Gov. Ned Lamont, a Democrat, who appoints most of the regents, should be embarrassed.

Democratic state legislators should be embarrassed too. They should be emboldened to ask more critical questions of the regents and college administrators generally. Legislators could start with: Is it really impossible to hire a competent, public-spirited administrator for less than a half million dollars per year?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Horses still allowed to share?

Map of the various alignments of the Boston Post Road. Scanned from S. Jenkins, The old Boston Post Road, (G.P. Putnam and Sons, New York and London, 1914)

Quick, before they wilt

“An Echo of Gratitude’’ (archival inkjet print), by Widline Cadet, in a group show through Aug. 22 at The Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown, Mass.

Julie Walsh: Dangerous misinformation campaigns from medieval Europe to today’s social media

Representation of the Salem witch trials (1692-1693) lithograph from 1892

Torturing woman accused of witchcraft, in this 1577 picture.

From The Conversation, except for images above

Julie Walsh is Whitehead Associate Professor of Critical Thought and Associate Professor of Philosophy, Wellesley College

She receives funding from the National Science Foundation

WELLESLEY, Mass.

Between 1400 and 1780, an estimated 100,000 people, mostly women, were prosecuted for witchcraft in Europe. About half that number were executed – killings motivated by a constellation of beliefs about women, truth, evil and magic.

But the witch hunts could not have had the reach they did without the media machinery that made them possible: an industry of printed manuals that taught readers how to find and exterminate witches.

I regularly teach a class on philosophy and witchcraft, where we discuss the religious, social, economic and philosophical contexts of early modern witch hunts in Europe and colonial America. I also teach and research the ethics of digital technologies.

These fields aren’t as different as they seem. The parallels between the spread of false information in the witch-hunting era and in today’s online information ecosystem are striking – and instructive.

Birth of a publishing empire

The printing press, invented around 1440, revolutionized how information spread – helping to create the era’s equivalent of a viral conspiracy theory.

By 1486, two Dominican friars had published the “Malleus Maleficarum,” or “Hammer of Witches.” The book has three central claims that came to dominate the witch hunts.

A 1669 edition of ‘Malleus Maleficarum.’ Wellcome Collection/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

First, it describes women as morally weak and therefore more likely to be witches. Second, it tightly links witchcraft with sexuality. The authors claim that women are sexually insatiable – part of what leads them to witchcraft. Third, witchcraft involves a pact with the devil, who tempts would-be witches through pleasures such as orgies and sexual favors. After establishing these “facts,” the authors conclude with instructions for interrogating, torturing and punishing witches.

The book was a hit. It had more than two dozen editions and was translated into multiple languages. While “Malleus Maleficarum” was not the only text of its kind, its influence was enormous.

Prior to 1500, witch hunts in Europe were rare. But after the “Malleus Maleficarum,” they picked up steam. Indeed, new printings of the book correlate with surges in witch-hunting in Central Europe. The book’s success wasn’t just about content; it was about credibility. Pope Innocent VIII had recently affirmed the existence of witches and conferred authority on inquisitors to persecute them, giving the book further authority.

Ideas about witches from earlier texts and folklore – such as the “fact” that witches could use spells to make penises vanish – were recycled and repackaged in the “Malleus Maleficarum,” which in turn served as a “source” for future works. It was often quoted in later manuals and woven into civic law.

The popularity and influence of the book helped crystallize a new domain of expertise: demonologist, an expert on the nefarious activities of witches. As demonologists repeated one another’s spurious claims, an echo chamber of “evidence” was born. The identity of the witch was thus formalized: dangerous and decisively female.

Skeptics fight back

Not everyone bought into the witch hysteria. As early as 1563, dissenting voices emerged – though, notably, most didn’t argue that witches weren’t real. Instead, they questioned the methods used to identify and prosecute them.

Essayist Michel de Montaigne, painted around 1578 by an unknown artist. Conde Museum/Wikimedia Commons

Dutch physician Johann Weyer argued that women accused of witchcraft were suffering from melancholia – what we might now call mental illness – and needed medical treatment, not execution. In 1580, French philosopher Michel de Montaigne visited imprisoned witches and concluded they needed “hellebore rather than hemlock”: medicine rather than poison.

These skeptics also identified something more insidious: the moral responsibility of people spreading the stories. In 1677, English chaplain, physician and philosopher John Webster wrote a scathing critique, claiming that most demonologists’ texts were straightforward copy and paste jobs where the authors repeated one another’s lies. The demonologists offered no original analysis, no evidence and no witnesses – failing to meet the standards of good scholarship.

The cost of this failure was enormous. As Montaigne wrote, “The witches of my neighborhood are in mortal danger every time some new author comes along and attests to the reality of their visions.”

Demonologists benefited from the social and political status associated with the popularity of their books. The financial benefit was, for the most part, enjoyed by the printers and booksellers – what today we refer to as publishers.

Witch hunts petered out throughout the 1700s across Europe. Doubt about the standards of evidence, and increased awareness that accused “witches” may have been suffering from delusion, were factors in the end of the persecution. The skeptics’ voices were heard.

Psychology of viral lies

Early modern skeptics understood something we’re still grappling with today: Certain people are more vulnerable to believing extraordinary claims. They identified “melancholics,” people predisposed to anxiety and fantastical thinking, as particularly susceptible.

Nicolas Malebranche, a 17th-century French philosopher, believed that our imaginations have enormous power to convince us of things that are not true – especially fear of invisible, malevolent forces. He noted that “extravagant tales of witchcraft are taken as authentic histories,” increasing people’s credulity. The more stories, and the more they were told, the greater the influence on the imagination. The repetition served as false confirmation.

“If they were to cease punishing (women accused of witchcraft) and treat them as mad people,” Malebranche wrote, “in a little while they would no longer be sorcerers.”

The title page of a treatise on witchcraft from 1613. Wellcome Collection/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Today’s researchers have identified similar patterns in how misinformation and disinformation – false information intended to confuse or manipulate people – spreads online. We’re more likely to believe stories that feel familiar, stories that connect to content we’ve previously seen. Likes, shares and retweets becomes proxies for truth. Emotional content designed to shock or outrage spreads far and fast.

Social media channels are particularly fertile ground. Companies’ algorithms are designed to maximize engagement, so a post that receives likes, shares and comments will be shown to more people. The more viewers, the higher the likelihood of more engagement, and so on – creating a cycle of confirmation bias.

Speed of a keystroke

Early modern skeptics reserved their harshest criticism not for those who believed in witches but for those who spread the stories. Yet they were curiously silent on the ultimate arbiters and financial beneficiaries of what got printed and circulated: the publishers.

Today, 54% of American adults get at least some news from social media platforms. These platforms, like the printing presses of old, don’t just distribute information. They shape what we believe through algorithms that prioritize engagement over accuracy: The more a story is repeated, the more priority it gets.

The witch hunts offer a sobering reminder that delusion and misinformation are recurring features of human society, especially during times of technological change and social upheaval. As we navigate our own information revolution, those early skeptics’ questions remain urgent: Who bears responsibility when false information leads to real harm? How do we protect the most vulnerable from exploitation by those who profit from confusion and fear?

In an age when anyone can be a publisher, and extravagant tales spread at the speed of a keystroke, understanding how previous societies dealt with similar challenges isn’t just academic – it’s essential.

Haze from western fires?

“Fork Shaped Tree” (archival pigment print on paper), by Joyce Tenneson, at the Fitchburg (Mass.) Art Museum.

Escaping the valley heat

“Herd on the Ridge” (oil on canvas), by Robert Chapla, in his joint show, “Colorful Edge of Soul,’’ with Valery Mahuchy at the the Gallery at WREN, Bethlehem, N.H., through Aug. 29.

Mt. Agassiz, in Bethlehem, N.H., in a colorized 1906 postcard.

The gallery says the show features paintings and collage. “Using Fauvist color and organic, fluid shapes and texture, Chapla and Mahuchy forge a visual and spiritual relationship with the world around them.’’

Tom Courage: Mantis summer at a Providence law firm

Praying Mantis

Photo by Mihai C. Popa

Industrial Trust Building, aka “Superman Building,’’ in downtown Providence. It’s been empty since 2013.

Tom Courage, a retired partner at the Providence-based law firm of Hinckley Allen, sent us this.

Law firms used to be quiet places in the summer. In many places the courts shut down during the summer, or at least slowed their pace to a crawl.

At my firm, young lawyers could only take vacations during the summer. Many offices shut down when the temperature exceeded a certain level.

Hinckley Allen had a legendary senior litigation partner named Matthew Goering. About half of the firm stories during my tenure were about Mr. Goering, who combined gruffness with an absurdly stilted Victorian manner of speech.

We also had a young litigation attorney, Thomas Gidley (who grew into legend, but was still a mortal person at the time of the events described here). Gidley, a graduate of Dartmouth College and Yale Law School, was one of the most literate attorneys I ever met, able to quote and draw on the wisdom of Chaucer, Yeats and everyone in between at will, and on any subject.

This was complemented by a dark sense of humor and redneck political views, which he displayed openly and with undisguised relish. This went along with being a conspicuously provocative Yankee fan in the midst of Red Sox Nation. You could not be around Gidley for very long without witnessing his reverence for Ronald Reagan and Reggie Jackson, his twin deities.

In short, Gidley was a fun person to be around. (Ed. note: this is actually true.)

Shortly after Gidley’s arrival at the firm, in the late 1960’s, Providence was afflicted by a cycle reminiscent of the plagues of Egypt, except with Praying Mantises instead of locusts. The windows were kept open, and Praying Mantises happily body surfed on the breezes through our offices in the Superman Building.

At the end of the work day, Gidley had just made his way uphill through the sweltering air to his modest quarters on the East Side when his phone rang. Worse, it was Mr. Goering. Mr. Goering’s voice needed no personal introduction, and never received one.

“Are you inextricably occupied?” was the terrifying growl transmitted over the telephone wires, words from which no deliverance would be forthcoming. In short order, Gidley found himself occupied in Mr. Goering’s living room, in the presence of Mr. Goering, Mr. Goering’s pet bulldog, and a small cardboard box held by Mr. Goering.

It is the box that requires an explanation, but this story cannot be told without first taking due note of Mr. Goering’s dog. Everyone knows the meme about owners looking like their dogs; what makes this story unique is the broad consensus that, in this case, it was Mr. Goering who looked like that first.

Okay, the box. The point of the box was that it was the perfect size for incarcerating Praying Mantises.

Your author must apologize for the reader’s justifiable impatience. Every story has its salient facts. The problem with this story is that these facts cannot all be told first. So let me lay it out in what might be seen in retrospect as a coherent sequence. Salient fact #1: Mr Goering’s wife took justifiable pride in her rose garden. Salient fact #2: the same weather conditions that caused a plague of Praying Mantises also caused a plague of Japanese Beetles. Salient fact #3: Japanese Beetles eat roses. Salient fact #4: Praying Mantises eat Japanese Beetles.

Your author is visualizing that the perceptive reader has processed the salient facts, and that the story is already taking shape in the reader’s mind.

And, indeed, the next morning found the young Dartmouth and Yale Law School graduate (in his neatly pressed blue suit) crawling on all fours among the parapets of the Superman Building, 400 feet above the traffic humming on the streets below, hunting down the Praying Mantises that would hopefully save Mrs. Goering’s roses. And stuffing them in the cardboard box so thoughtfully provided by Mr. Goering.

All of us (then) young lawyers agreed: It was pretty much a typical day in the life of a young Hinckley Allen lawyer.

Epilogue

There are those who suppose that life in a law firm is one of dreary monotony, every spark of human imagination snuffed out by ponderous Latin phrases. Your author himself can’t help but wonder what “real life” would have been like.

I’d rather be the tree

Squash flowers

From “Squash in Blossom,’’ by poet Robert Francis (1901-1987). He lived most of his life in Amherst, Mass., in the Connecticut River Valley, New England’s dominant agricultural area

“Let the squash be what it was doomed to be

By the old Gardener with the shrewd green thumb.

Let it expand and sprawl, defenceless, dumb.

But let me be the fiber-disciplined tree

“Whose leaf (with something to say in wind) is small,

Reduced to the ingenuity of a green splinter

Sharp to defy or fraternize with winter,

Or if not that, prepared in fall to fall.’’

A time for reflection

“Laid Back, Eastern Chimpanzee, Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania’’(photo), by Tom Mangelsen, at Springfield (Mass.) Museums, in the ongoing show “Comedy Wildlife Photography Awards.’’

Philip K. Howard: A way to reboot America

This is a lightly edited version of a press release touting my old friend Philip K. Howard’s latest book. The New York-based lawyer, civic leader and photographer is chairman of the nonprofit reform organization Common Good.

In Saving Can-Do: How to Revive the Spirit of America civic philosopher Howard proposes a governing framework to revive America’s can-do culture — not by DOGE’s Indiscriminate Cuts, and nor by “Abundance”.

Saving Can-Do shows why the waste and paralysis of the red-tape state can be cured only by a new governing framework that empowers human responsibility on the spot. Letting Americans use common sense also holds the key to relieving populist resentment.

This brief book, to be published by Rodin Books on Sept. 23, responds to Americans’ desire for government that delivers results, not overbearing red tape.

“Washington needs to be rebooted, but neither party presents a vision to do this,” Howard notes.

“Republicans focus on cutting programs, not making them work. Democrats want to throw more money at a failing system. Aspiring to abundance is important, but escaping bureaucratic quicksand requires a radical shift in governing philosophy — replacing the red-tape compliance system with a framework activated by human responsibility.”

All societies periodically undergo a major shift in the social order. America is at one of those moments of change, and needs a coherent new overhaul vision to avoid the risks of extremism.

President Trump is swinging a wrecking ball at the status quo, but has no plan for how Washington will work better the day after DOGE. Democrats are in denial, waiting their turn to run a bloated government that Americans increasingly loathe.

Saving Can-Do offers a dramatically simpler governing vision: Replace red tape with responsibility. Let Americans use their judgment. Let other Americans hold them accountable for their results and their values.

“The geniuses in the 1960s tried to create a government better than people,” Howard says. “Just follow the rules. Or prove that your judgment about someone is fair. But how do you prove who has poor judgment, or doesn’t try hard? Bureaucracy makes people go brain dead—so focused on mindless compliance that they can’t solve the problem before them. Americans hate it.”

“We must scrap the red tape state,” argues Howard. “New leadership is not sufficient, because the new leaders will be shackled by rigid legal mandates. Trying to prune the red tape still leaves a jungle of other mandates.’’

“What’s required is a multi-year effort to replace command-and-control bureaucracies with simpler codes that delineate the authority to make tradeoff judgments. The idea is not radical, but traditional— it’s the operating philosophy of the U.S. Constitution. As America approaches the 250th anniversary of the revolution, it’s time to reclaim the magic of America’s unique can-do culture.”

For more information, please contact Henry Miller at hmiller@highimpactpartnering.com.

SELECTED PRAISE FOR PHILIP HOWARD’S PREVIOUS BOOKS

Everyday Freedom, Rodin Books, 2024

“Everyday Freedom offers a master class in consequences of lost agency. Agency not only promotes freedom, but its deprivation through policies and regulations saps civil vitality. Politicians’ inattentiveness to the problem stokes alienation and populism. Re-empowering individuals can produce a can-do, let ‘er rip economy of opportunity and flourishing. We’ve corrected such ‘system failure’ before, and Howard provides a roadmap for doing so again. The book is a must read for any student of what ails this society—that is, all of us.”

— Glenn Hubbard, Russell L. Carson Professor of Economics and Finance, Columbia University, and former chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers.

Not Accountable, Rodin Books, 2023

“I love cities and want them to thrive. Philip Howard shows a major reason why American cities struggle, and why they fail so many of their citizens: public employee unions prevent accountability, efficiency, and reform.

“Howard’s novel insight: Their power is not only unconscionable, for its harm to the public good; it might also be unconstitutional.”

— Jonathan Haidt, Thomas Cooley Professor of Ethical Leadership at New York University’s Stern School of Business, author of The Righteous Mind and co-author of The Coddling of the American Mind.

Try Common Sense, W. W. Norton, 2019

“A thunderous little book.”

— Gillian Tett, Financial Times

The Rule of Nobody, W. W. Norton, 2014

“Philip Howard offers a startlingly fresh slant on what is holding America back. No one is free to make choices, including, especially, government officials. Regulatory law has become a nearly impenetrable web of detailed prohibitions and specifications. Everyone is hamstrung. Dense regulation discourages individuals, communities, and companies from taking new initiatives. It also prevents government officials from making the case by case judgment needed for effective regulatory oversight.”

— Edmund S. Phelps, winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Economics

Life Without Lawyers, W. W. Norton, 2009

“Philip Howard’s Life Without Lawyers hits the nail on the head -– incoherent legalities stultify necessary change and frustrate attempts to use common sense in solving the problems that face our country. This is a real wake-up call from one of America’s finest public minds.”

—Bill Bradley, former U.S. senator

The Collapse of the Common Good, Ballantine Books, 2007

“Philip K. Howard’s book rings true. Teachers have such a hard time being themselves, dragging around the millstone of bureaucracy. Will all our well-intentioned efforts to regulate and manage our way to social welfare backfire, creating a society where people aren’t free to exercise their own judgment and good will?”

— Wendy Kopp, founder and president of Teach for America

The Death of Common Sense, Random House, 1995

“A brilliant diagnosis … forceful, trenchant, and eloquent.”

— Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Pulitzer Prize-winning historian.

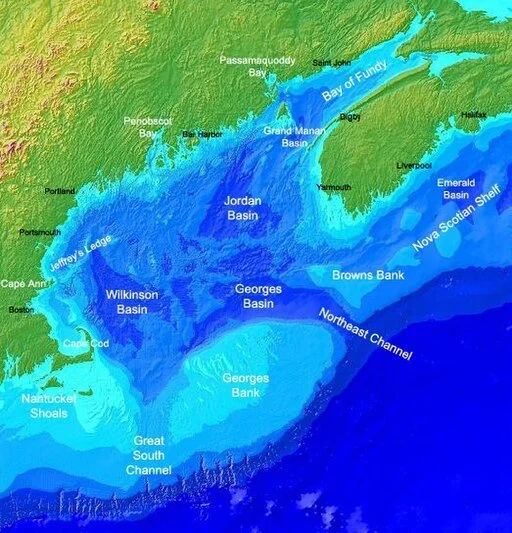

Can we import power from Nova Scotia wind farms?

Some have suggested laying an underwater cable to send power from wind farms off Nova Scotia to southern New England.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com.

Given local opposition by some to current and proposed wind-farm projects off southern New England and the Trump administration’s dislike of wind-power projects, and, indeed, of “green energy” in general, it’s perhaps not surprising that Massachusetts officials are sounding out Canada about getting power from planned offshore wind projects around Nova Scotia.

Of course, this would pose such challenges as the need to install extra transmission capacity to bring the power to southern New England and would undermine hopes for jobs in construction and maintenance for offshore wind projects in our region. And building a transmission line on land could face the sort of pushback from powerful groups and localities that has long delayed such projects as getting more hydroelectricity from Quebec into New England.

Of course, laying a mostly underwater line would be possible but would present problems, too, perhaps including complaints from fishermen.

And would Trump seek a way to put a tariff on that electricity?

We should bear in mind that Trump’s gyrational tariffs and his threats to take over what had been such a friendly ally have created long-term distrust and animosity there toward our crazy country, which over time will do considerable economic and geopolitical damage to the United States.

Meanwhile, visits by Canadians to New England, a region our northern neighbors have long favored, continue to fall because of Trump policies.