Llewellyn King: The agony of statelessness

Stateless children at at the Schauenstein, Germany, displaced-persons camp in about 1946. There were millions of displaced and stateless people in Europe as World War II ended.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have only known one stateless person. You don't get a medal for it or wear a lapel pin.

The stateless are the hapless who live in the shadows, in fear.

They don't know where the next misadventure will come from: It could be deportation, imprisonment or an enslavement of the kind the late Johnny Prokov suffered as a shipboard stowaway for seven years.

His story ended well, but few do.

When I knew Johnny, he was a revered bartender at the National Press Club in Washington. By then, he had American citizenship, was married and lived a normal life.

It hadn't always been that way. He told me that he had come from Dalmatia, when that area was so poor people took their clothes to a specialist who would kill the lice in the seams with a little wooden mallet, which wouldn't damage the cloth.

To escape that extreme poverty, Prokov became a stowaway on a ship.

So began his seven-year odyssey of exploitation and fear of violence. The captains took advantage of the free labor and total servitude of the stowaways.

Eventually, Prokov jumped ship in Mexico. He made his way to the United States, where a life worth living was available.

I don't know the details of how he became a citizen, but he dreamed the American dream — and it came true for him.

An odd legacy of his years at sea was that Prokov had become a brilliant chess player. He would often have as many as a dozen chess games going along the bar in the National Press Club. He always won. He had had time to practice.

The United Nations says there are 4 million stateless people in the world, but that is a massive undercount. Many of those who are stateless are refugees and have no idea if they are entitled to claim citizenship of the countries they are desperate to escape from. Citizenship in Gaza?

Now the Trump administration wants to add to the number of stateless people by denying birthright citizenship to children born of illegal immigrants in the United States.

It wants to deny people — who are in all ways Americans — their constitutional right of citizenship. Their lives will be lived on a lower rung than their friends and contemporaries. They will be denied passports, maybe education, possibly medical care, and the ability to emigrate to any country that otherwise might have received them.

Instead, they will live their lives in the shadows, children of a lesser God, probably destined to have children of their own who might also be deemed noncitizens. They didn't choose the womb that bore them, nor did they sanction the actions of their parents.

The world is awash in refugees fleeing war, crime and violence, and environmental collapse. Those desperate people will seek refuge in countries which can't absorb them and will take strong actions to keep them out, as have the United States and, increasingly, countries in Europe.

There is a point, particularly in Europe, where the culture, including established religion, is threatened by different cultures and clashing religions.

But when it comes to children born in America to mothers who live in America, why mint a new class of stateless people, condemned to a second-class life here, or deport them to some country, such as Rwanda or Uganda, where its own people are already living in abject poverty?

All immigrants can't be accommodated, but the cruelty that now passes for policy is hurtful to those who have worked hard and dared to seek a better life for themselves and their children.

It is bad enough that millions of people are seeking somewhere to live and perchance a better life, due to war or crime or drought or political follies.

To extend the numbers by denying citizenship to the children of parents who live and work here isn't good policy. It is also unconstitutional.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the administration, it will add social instability of haunting proportions.

Children are proud of their native lands. What will the new second class be proud of — the home that denied them?

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant.

Llewellyn King: Will AI launch a shadow government that can catch Trump, et al., trying to cook the books?

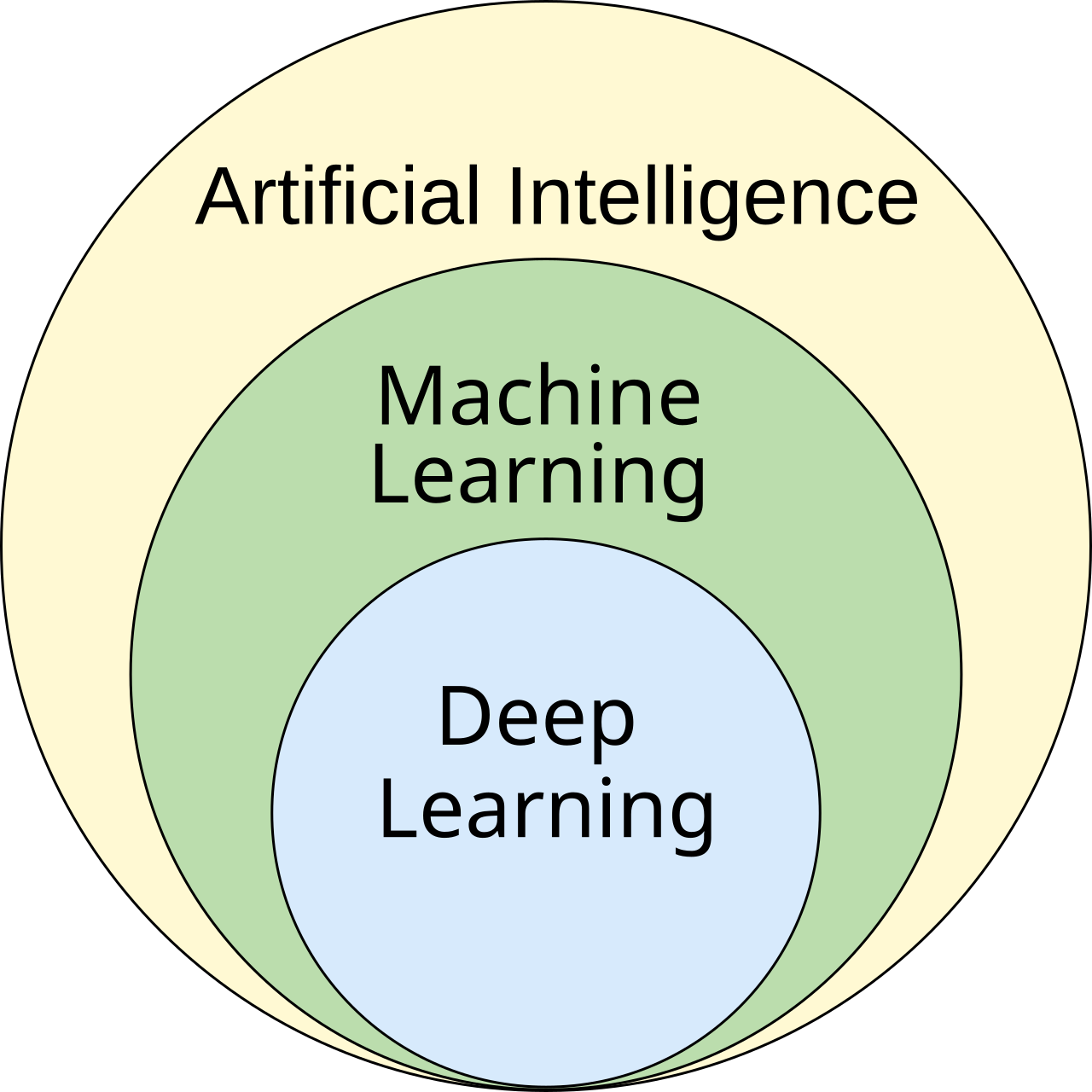

Read about a meeting of the minds at a summer workshop at Dartmouth College in 1956 that helped launch artificial intelligence as a discipline and gave it a name.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

This Time It’s Different is the title of a book by Omar Hatamleh on the impact of artificial intelligence on everything.

By this Hatamleh, who is NASA Goddard Space Flight Center’s chief artificial intelligence officer, means that we shouldn’t look to previous technological revolutions to understand the scope and the totality of the AI revolution. It is, he believes, bigger and more transformative than anything that has yet happened.

He says AI is exponential and human thinking is linear. I think that means we can’t get our minds around it.

Jeffrey Cole, director of the Center For the Digital Future at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, echoes Hatamleh.

Cole believes that AI will be as impactful as the printing press, the internet and COVID-19. He also believes 2027 will be a seminal year: a year in which AI will batter the workforce, particularly white-collar workers.

For journalists, AI presents two challenges: jobs lost to AI writing and editing, and the loss of truth. How can we identify AI-generated misinformation? The New York Times said simply: We can’t.

But I am more optimistic.

I have been reporting on AI since well before ChatGPT launched in November 2022. Eventually, I think AI will be able to control itself, to red flag its own excesses and those who are abusing it with fake information.

I base this rather outlandish conclusion on the idea that AI has a near-human dimension which it gets from absorbing all published human knowledge and that knowledge is full of discipline, morals and strictures. Surely, these are also absorbed in the neural networks.

I have tested this concept on AI savants across the spectrum for several years. They all had the same response: It is a great question.

Besides its trumpeted use in advancing medicine at warp speed, AI could become more useful in providing truth where it has been concealed by political skullduggery or phony research.

Consider the general apprehension that President Trump may order the Bureau of Labor Statistics to cook the books.

Well, aficionados in the world of national security and AI tell me that AI could easily scour all available data on employment, job vacancies and inflation and presto: reliable numbers. The key, USC’s Cole emphasizes, is inputting complete prompts.

In other words, AI could check the data put out by the government. Which leads to the possibility of a kind of AI shadow government, revealing falsehoods and correcting speculation.

If AI poses a huge possibility for misinformation, it also must have within it the ability to verify truth, to set the record straight, to be a gargantuan fact checker.

A truth central for the government, immune to insults, out of the reach of the FBI, ICE or the Justice Department —and, above all, a truth-speaking force that won’t be primaried.

The idea of shadow government isn’t confined to what might be done by AI, but is already taking shape where DOGEing has left missions shattered, people distraught and sometimes an agency unable to perform. So, networks of resolute civil servants inside and outside government are working to preserve data, hide critical discoveries and to keep vital research alive. This kind of shadow activity is taking place at the Agriculture, Commerce, Energy and Defense departments, the National Institutes of Health and those who interface with them in the research community.

In the wider world, job loss to AI, or if you want to be optimistic, job adjustment has already begun. It will accelerate but can be absorbed once we recognize the need to reshape the workforce. Is it time to pick a new career or at least think about it?

The political class, all of it, is out to lunch. Instead of wrangling about social issues, it should be looking to the future, a future which has a new force, much as automation was a force to be accommodated, this revolution can’t be legislated or regulated into submission, but it can be managed and prepared for. Like all great changes, it is redolent with possibility and fear.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.