We’re all a bunch

“Quartet,’’ by Kathryn Geismar, in the group show “Selfhood,’’ at the Danforth Art Museum, Framingham, Mass., though June.

She says:

“My work explores the complex and often fragmentary nature of identity through portraits and abstract collage. My recent figurative series depicts adolescents ranging in age from 14-21. These young adults are claiming an identity in an age when binary definitions of self are under question….Figures move in and out of focus; layers of mylar promote looking through; grommets pierce through layers like jewelry and at other times like windows into layers below.’’

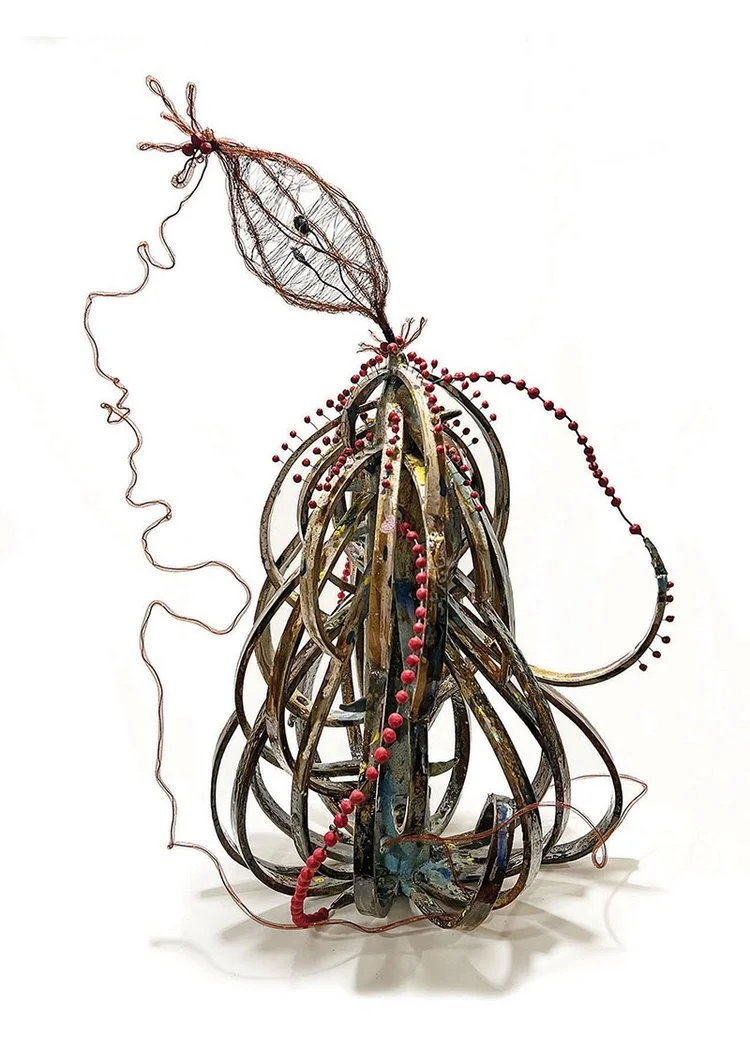

In life’s tangled web

Work by Jongeun Gina Lee in her show “Shift,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston through June 29.

From her artist’s statement:

“I imagine each piece I make is on its own journey, just like everything in Nature transforms in lineage of time and space. I decenter myself and find peace accepting I am a tiny part of a larger cycle. It allows me to cope with turbulences and disappointments in life. I observe resilience and balance in precarious journeys of all existence in nature, while all suffers from the vulnerability and randomness of existence…. The current body of works represents slow incubation of inner strength, cautious hope and resilience with optimism in life. The empty but charged space using linear elements articulates the hidden energy in nature which transforms and pushes everything through its journey. The assembly of linear units in my forms is a metaphor of paradoxical adaptability in time and space.’’

Elic Weitzel: The rise, fall and rise of white-tailed deer

A white-tailed deer

From The Conversation (except for image above):

Elic Weitzel is Peter Buck P0stdoctoral Research Fellow at the Smithsonian Institution.

Elic Weitzel received funding from the National Science Foundation (award #2128707) to support this research.

Given their abundance in American backyards, gardens and highway corridors these days, it may be surprising to learn that white-tailed deer were nearly extinct about a century ago. While they currently number somewhere in the range of 30 million to 35 million, at the turn of the 20th Century, there were as few as 300,000 whitetails across the entire continent: just 1% of the current population.

This near-disappearance of deer was much discussed at the time. In 1854, Henry David Thoreau had written that no deer had been hunted near Concord, Massachusetts, for a generation. In his famous “Walden,” he reported that:

“One man still preserves the horns of the last deer that was killed in this vicinity, and another has told me the particulars of the hunt in which his uncle was engaged. The hunters were formerly a numerous and merry crew here.”

But what happened to white-tailed deer? What drove them nearly to extinction, and then what brought them back from the brink?

As a historical ecologist and environmental archaeologist, I have made it my job to answer these questions. Over the past decade, I’ve studied white-tailed deer bones from archaeological sites across the eastern United States, as well as historical records and ecological data, to help piece together the story of this species.

Precolonial rise of deer populations

White-tailed deer have been hunted from the earliest migrations of people into North America, over 15,000 years ago. The species was far from the most important food resource at that time, though.

Archaeological evidence suggests that white-tailed deer abundance only began to increase after the extinction of megafauna species like mammoths and mastodons opened up ecological niches for deer to fill. Deer bones become very common in archaeological sites from about 6,000 years ago onward, reflecting the economic and cultural importance of the species for Indigenous peoples.

A 16th-Century engraving of Indigenous Floridians hunting deer while disguised in deerskins. Theodor de Bry/DEA Picture Library/De Agostini via Getty Images

Despite being so frequently hunted, deer populations do not seem to have appreciably declined due to Indigenous hunting prior to AD 1600. Unlike elk or sturgeon, whose numbers were reduced by Indigenous hunters and fishers, white-tailed deer seem to have been resilient to human predation. While archaeologists have found some evidence for human-caused declines in certain parts of North America, other cases are more ambiguous, and deer certainly remained abundant throughout the past several millennia.

Human use of fire could partly explain why white-tailed deer may have been resilient to hunting. Indigenous peoples across North America have long used controlled burning to promote ecosystem health, disturbing old vegetation to promote new growth. Deer love this sort of successional vegetation for food and cover, and thus thrive in previously burned habitats. Indigenous people may have therefore facilitated deer population growth, counteracting any harmful hunting pressure.

More research is needed, but even though some hunting pressure is evident, the general picture from the precolonial era is that deer seem to have been doing just fine for thousands of years. Ecologists estimate that there were roughly 30 million white-tailed deer in North America on the eve of European colonization – about the same number as today.

Elic Weitzel and volunteers excavate for deer bones at a 17th-century colonial site in Connecticut. Scott Brady

Colonial-era fall of deer numbers

To better understand how deer populations changed in the colonial era, I recently analyzed deer bones from two archaeological sites in what is now Connecticut. My analysis suggests that hunting pressure on white-tailed deer increased almost as soon as European colonists arrived.

At one site dated to the 11th to 14th centuries – before European colonization – I found that only about 7% to 10% of the deer killed were juveniles.

Hunters generally don’t take juvenile deer if they’re frequently encountering adults, since adult deer tend to be larger, offering more meat and bigger hides.

Additionally, hunting increases mortality on a deer herd but doesn’t directly affect fertility, so deer populations experiencing hunting pressure end up with juvenile-skewed age structures. For these reasons, this low percentage of juvenile deer prior to European colonization indicates minimal hunting pressure on local herds.

However, at a nearby site occupied during the 17th century – just after European colonization – between 22% and 31% of the deer hunted were juveniles, suggesting a substantial increase in hunting pressure.

Researchers can tell from the size and development of a deer’s bones its stage of life.

This elevated hunting pressure likely resulted from the transformation of deer into a commodity for the first time. Venison, antlers and deerskins may have long been exchanged within Indigenous trade networks, but things changed drastically in the 17th century. European colonists integrated North America into a trans-Atlantic mercantile capitalist economic system with no precedent in Indigenous society. This applied new pressures to the continent’s natural resources.

Deer – particularly their skins – were commodified and sold in markets in the colonies initially and, by the 18th century, in Europe as well. Deer were now being exploited by traders, merchants and manufacturers desiring profit, not simply hunters desiring meat or leather. It was the resulting hunting pressure that drove the species toward its extinction.

20th-century rebound of white-tailed deer

Thanks to the rise of the conservation movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, white-tailed deer survived their brush with extinction.

Concerned citizens and outdoorsmen feared for the fate of deer and other wildlife, and pushed for new legislative protections.

The Lacey Act of 1900, for example, banned interstate transport of poached game and – in combination with state-level protections – helped end commercial deer hunting by effectively de-commodifying the species. Aided by conservation-oriented hunting practices and reintroductions of deer from surviving populations to areas where they had been extirpated, white-tailed deer rebounded.

The story of white-tailed deer underscores an important fact: Humans are not inherently damaging to the environment. Hunting from the 17th through 19th centuries threatened the existence of white-tailed deer, but precolonial Indigenous hunting and environmental management appear to have been relatively sustainable, and modern regulatory governance in the 20th Century forestalled and reversed their looming extinction.

Sticky stuff

Pine cones releasing pollen.

“Now I know that summer is here, no matter how cold it is at night, for when I went out to the car this morning, the windshield was dusted with orange and the whole shiny dark blue of the body was powdered. The pine pollen has come! This is a thick, almost oily deposit that penetrates everything. If you close a room and lock the windows, the sills will be drifted with the pollen the next morning. The floors turn orange.’’

Gladys Taber, in My Own Cape Cod (1971)

Our ‘bitch-goddess’

“The moral flabbiness born of the exclusive worship of the bitch-goddess SUCCESS. That - with the squalid cash interpretation put on the word “success” -- is our national disease.’’

―William James (1842-1910), philosopher, psychologist and Harvard professor, in a 1906 letter to English writer H.G. Wells (1866-1946).

How does brain create its reality?

“Preponderance of Beech” (oil on linen), by Don Collins, in his show “Understory,’’ at AVA Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon, N.H., through June 28.

He says in his Web site:

“I am fascinated by the experience of encountering art, both for myself and for others. Contemporary brain science, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), gives tantalizing hints about how a brain creates its reality. I am interested in what that process means to an artist, the viewer and the creative experience that hangs between them.’’

Planting an urban mini-forest

Text below excerpted from ecoRI News

“PROVIDENCE — There was a method to the madness of planting 185 trees and 80 shrubs 2 to 3 feet apart in a 1,000-square-foot corner of the Pearl Street Garden.

“The method is named after Akira Miyawaki, a Japanese botanist and ecologist who specialized in natural vegetation restoration of degraded land. His method has been implemented worldwide. He died in 2021 at the age of 93.

“The Miyawaki Method focuses on swiftly creating dense, biodiverse forests — or, in the case of the Pearl Street Garden, a microforest — using native vegetation. The practice involves planting seedlings at high density, to mimic natural forest ecosystems and to rely on natural processes such as competition and mutualism to accelerate growth….”

But they keep all their clothes on

“Summer, New England” (1912 oil on canvas), by Maurice Prendergast (1858-1924), American painter

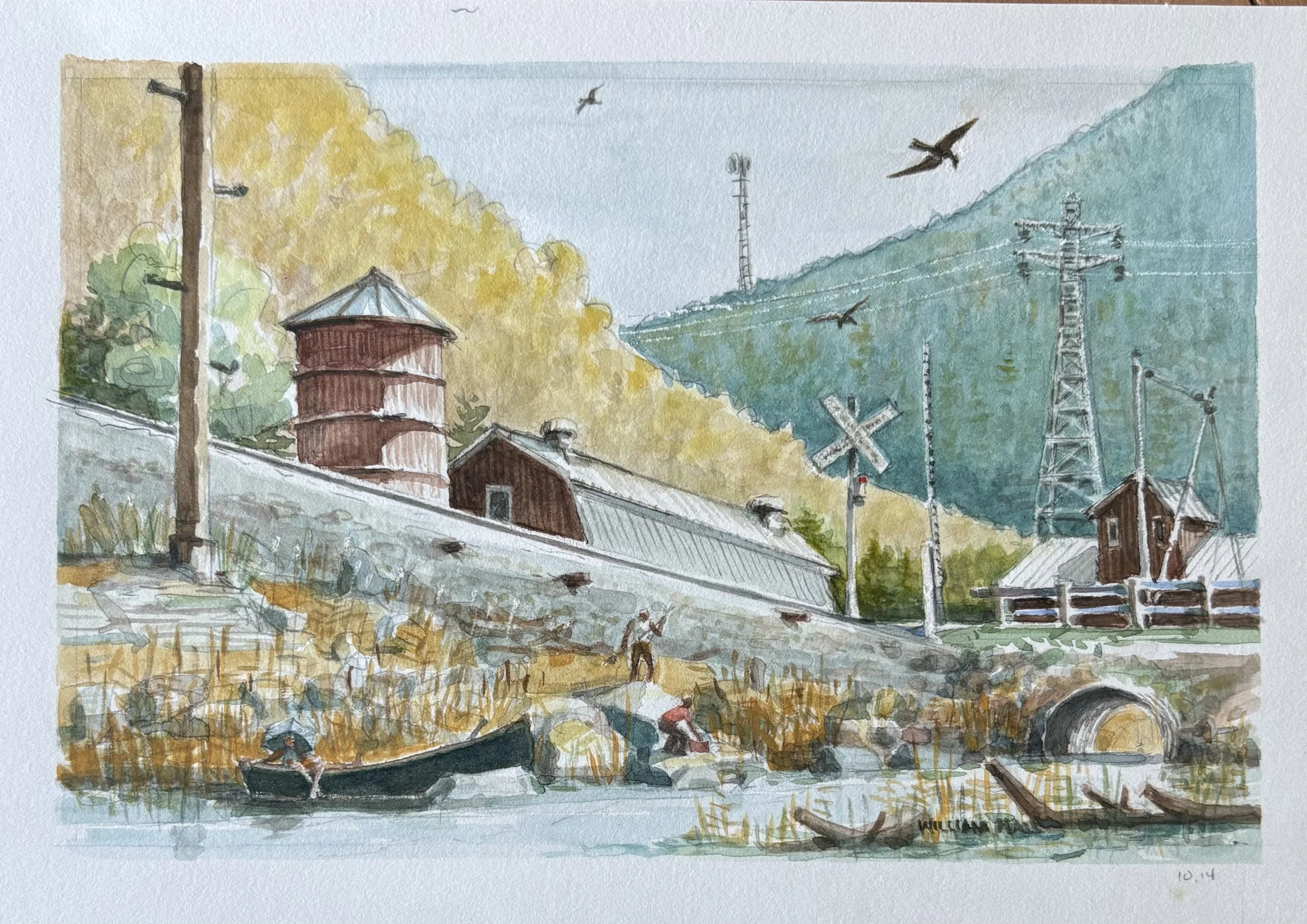

Through the mountains

“RR Crossing in a Valley” (watercolor), by William Talmadge Hall, in his “Obstruction to a Landscape’’ series. He’s based in Rhode Island and Florida but spent his early years in Vermont.

Llewellyn King: Harnessing power in new ways

The falls at such dams on New England rivers were used to power the region’s textile and other mills.

Northfield Mountain, in Northfield, Mass., FirstLight’s flagship facility, is New England’s largest energy-storage operation This giant water battery is capable of powering more than 1 million homes for up to 7.5 hours each day.

This article first appeared on Forbes.com

Virginia is the first state to formally press for the creation of a virtual power plant. Glenn Youngkin, the state’s Republican governor, signed the Community Energy Act on May 2, which mandates Dominion Energy to launch a 450-megawatt virtual power plant (VPP) pilot program.

Virginia isn’t alone in this endeavor, but it is certainly the most out front. There are many incipient VPPs clustered around utilities across the country.

A virtual power plant is the ultimate realization of something that has been going on for a long time as utilities have been hooking up various power sources, managed conservation and underused generation, known as distributed energy resources (DER). These, according to even small utilities, can contribute up to and possibly over 10 percent electricity to a utility system.

Organized and formalized and with enough coverage, DER becomes a VPP. Sometimes the terms are used interchangeably.

A virtual power plant not only depends on managed conservation and underused generation but also on some imaginative use of resources, like hooking up transportation fleets to discharge their batteries onto the grid when they aren’t in use. Electric school buses are frequently cited as playing a role in future VPPs. Conservation and solar roofs with related batteries are the backbone of DER and VPPs. Eventually, they are expected to be common to most utilities or consortia of utilities.

In Owings Mills, Md., an engineer and inventor with a slew of patents to his name, Key Han, dreams of a different kind of VPP, one which could, if widely deployed, provide a new source of baseload power.

Han, CEO and chief scientist at DDMotion, has pioneered speed-converter technology which, if widely deployed, would produce inexpensive, reliable energy in sufficient quantity to be described as baseload. Indeed, he said in an interview, “It would be a huge new source of baseload.”

Han’s technology converts variable energy inputs into constant speed outputs. For example, the flow of water in a stream is variable but with his speed-converter technology, the energy in the flow can be captured and converted to a constant speed output.

With his technology, grid-quality frequency can flow from many sources without extensive civil engineering or major construction, he told me. In particular, Han cited power dams, like the ones in New England which were built in the 19th Century to drive the textile mills.

“A simple harnessing module with a generator behind the spillway coupled with my technology can produce frequency that is constant and ready to go on the grid. If you have enough of these simple, low-cost generators installed, you have created a new baseload source, a virtual power plant of a different and exceptionally reliable kind,” Han said.

Another use of the same DDMotion technology would remedy what is becoming a growing problem for wind and solar generators: the lack of rotating inertia. Inertia is essential for utility operators to fix sudden changes in frequency caused by changes in generation or consumption (50 cycles in Europe and 60 cycles in the United States).

Lack of inertia has been blamed for the widespread blackout on the Iberian Peninsula and is becoming an issue for utilities with a lot of solar and wind generation, so called inverter power. This refers to the grooming with an inverter to power to grid-quality alternating current from its original direct current.

Here, again, his technology can inexpensively resolve the inertia problem for wind and solar generation, Han said. Either using a mechanical system or an electronic one, wind and solar systems could provide rotating inertia.

Increasingly, utilities are looking for untapped sources of power which can be bundled together into VPPs.

Renew Home, a Google-financed company, claims 3 gigawatts of electricity savings, which it says makes it the leader in VPPs. It relies on managing end-use load primarily in homes with load shedding of high energy-consuming devices during peaks. This is accomplished by using special thermostats and smart meters.

Industry experts believe artificial intelligence will be a key to extracting the most energy out of unconventional sources as well as fine tuning usage.

VPPs are here and many more are coming.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Subscribe to Llewellyn King's File on Substack

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Flaming landscape

“Red Fall Maple” (watercolor), by Sano Gofu (Japanese, 1888-1974), at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass.

Chris Powell: Distinguish among immigrants; Pratt & Whitney’s slow exit

Border between Nogales, Ariz., and Nogales, Mexico.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Leftist research and social-service groups are working with news organizations to blur the distinction between legal and illegal immigration.

It happened again the other week as Connecticut's Hearst newspapers touted a report from Data Haven and the Connecticut Immigrant Support Network about the contributions of immigrants, legal and illegal alike, to the state's economy.

The report says: “Politics that deter immigration, including those targeted at people who are legally authorized to work in the U.S., will harm the Connecticut economy. In particular, deporting undocumented immigrants, who comprise 3% of Connecticut's total population (about 117,000 people), would potentially wipe out tens of thousands of jobs, given that 87% of these immigrants are working age."

This is triply misleading.

First, the report falsely suggests that there is clamor in Connecticut to expel legal immigrants. To the contrary, Connecticut is happily full of citizens and legal residents of all sorts of foreign ancestry.

Second, the jobs held by illegal immigrants in Connecticut would not necessarily disappear if illegal immigrants disappeared. That's because the labor- participation rate in Connecticut -- the percentage of the adult population in the workforce -- has been declining for decades, from 71 percent in 1991 to 65 percent as of April, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. That is, there is slack in the state's workforce, and while many state residents are not highly skilled, a labor shortage might raise wages and draw unemployed people back into the workforce.

Third, the report holds that, insofar as they are working, legal and illegal immigrants are and should be considered the same.

But they're not the same.

Legal immigrants have been reviewed by immigration authorities for suitability to enter the country -- reviewed in regard to their intentions, behavior, health, ability to support themselves financially, associations, and any past immigration law violations.

But illegal immigrants typically have not been reviewed at all. Some probably have heard that state government in Connecticut obstructs and tries to nullify federal immigration law and provides financial and other benefits to illegal immigrants -- that the state believes that anyone who breaks into the United States illegally and reaches Connecticut should be exempt from immigration law.

That is the big issue here -- not the supposed economic benefits to the state from having a class of unenfranchised serfs working under the table, lowering wages for unskilled labor, but whether everyone entering the United States should be vetted and immigration law enforced or whether the borders should be as open again as they were during the Biden administration.

But in a debate in the state House of Representatives the other day, Democratic Majority Leader Jason Rojas argued that no distinction should be made between legal and illegal immigrants. “We should reject referring to them as illegal," he said.

Journalists covering the immigration issue in Connecticut seem to agree. They rarely put the question of undifferentiated immigration to its advocates -- not even to the governor, members of Congress, and Rojas and other state legislators.

Pratt & Whitney headquarters in East Hartford, Conn.

During the recent strike at Pratt & Whitney, a member of the machinists union wrote to the Waterbury Republican-American complaining that the company has been transferring jet-engine-parts manufacturing work out of Connecticut to a new factory in North Carolina, threatening job security for the company's workers here.

This is actually an old story. Sixty years ago Pratt & Whitney had more than 20,000 employees in Connecticut. Today it has only half as many in the state but 43,000 around the country and worldwide.

Expanding elsewhere has been the company's policy for decades. Part of it is economizing, since labor is usually cheaper and taxes lower outside Connecticut. But the bigger part of it is the politics of being a major military contractor needing to build congressional support throughout the country. Whether a weapons system works well can be less important than which states profit from it.

Loyalty to one's origins doesn't mean much in big business anymore. It doesn't help that state government, ever oblivious, keeps making Connecticut more expensive.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Finding good bear bait

“If you can’t write something it’s because you don’t know enough. I tell my writers at work that if they are stuck they need to go do more interviews. The writing is hard if you’re trying to bluff people and pretend you know more than you know. It’s easy when you’ve done all the legwork.

“Let me give you an example from my own life. I write about Maine game wardens and I’ll often run into a problem. Wait a second? I’ll think. How does a warden trap a bear? What does he use for bait? I know doughnuts and bacon grease and lobster shells work, but I want my game warden to be an expert woodsman. And I’ll stop writing because I am blocked. The only solution is to call a warden and he’ll tell me that the secret ingredient in good bear bait is propane. Actually it’s a chemical called ethyl mercaptan, which bears love for some reason. I bet you didn’t know that. And neither did I until I made that phone call.’’

— From Paul Doiron’s commencement address at the University of Maine at Augusta in May 11, 2013. He’s a crime novelist and former editor of Down East magazine.

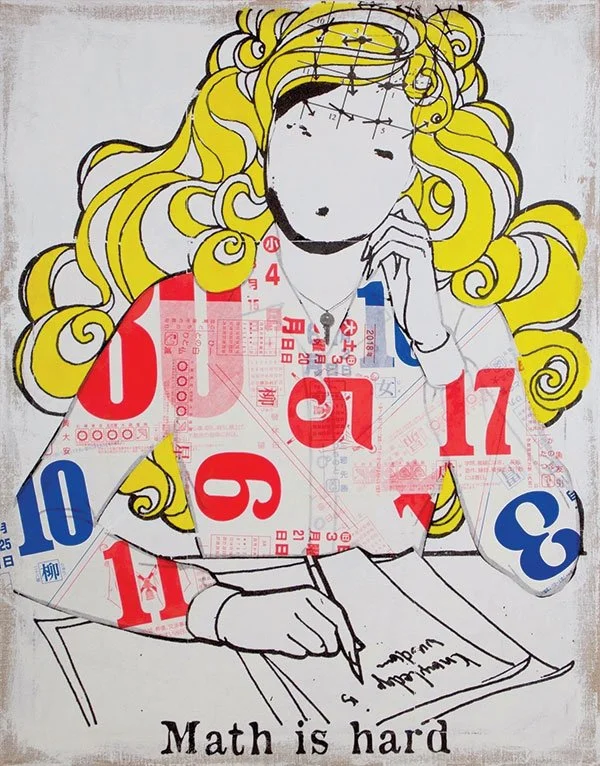

That’s why it’s so useful

“Math is Hard,’’ by Stephanie Todhunter, at Cambridge (Mass.) Art Association

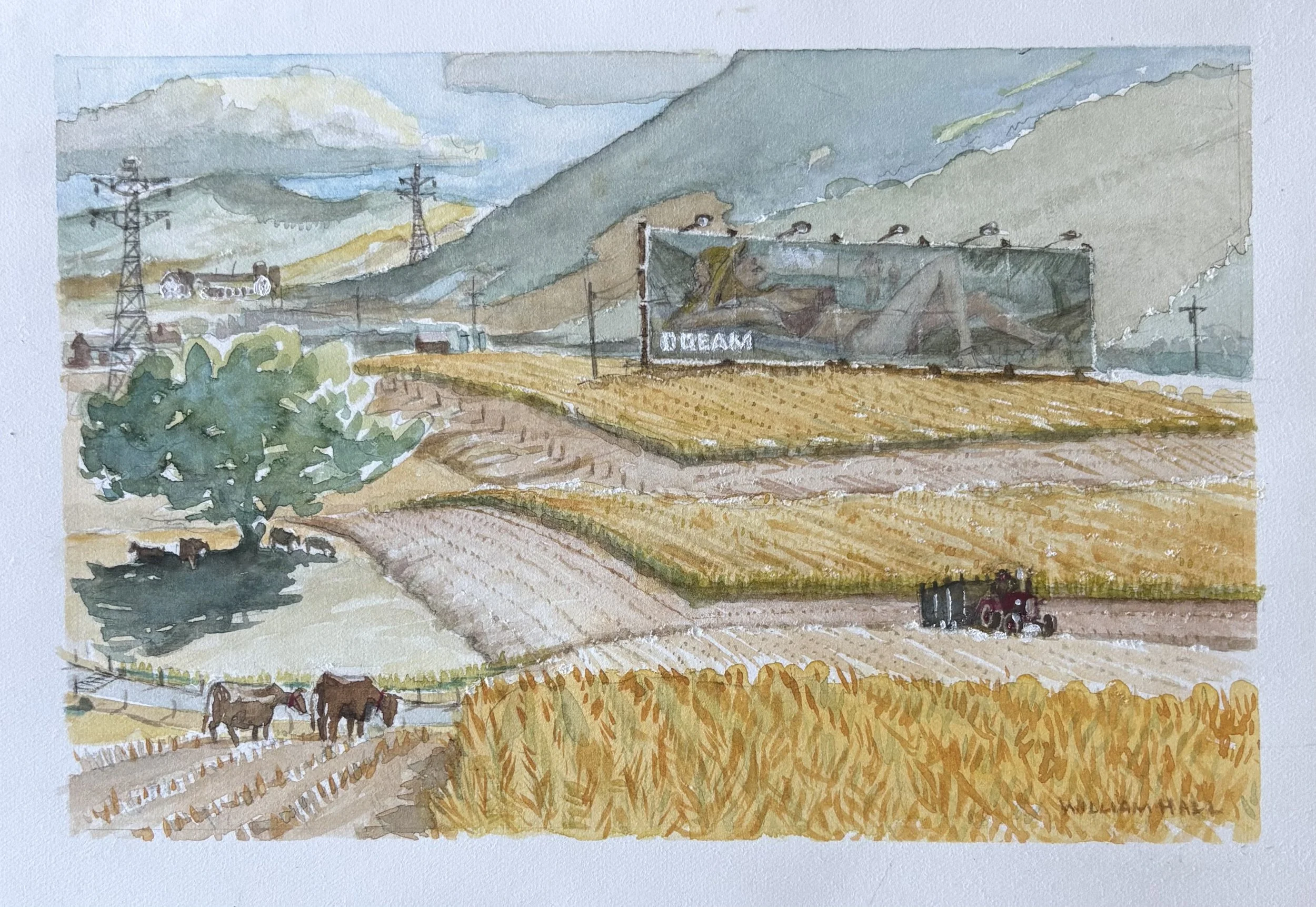

Roadside distractions

“Billboard in a Cornfield” (watercolor), by Rhode Island-and-Florida-based artist William T. Hall, in his series “Obstructions to a Landscape.’’

Jury is still out on Copley Square changes

Statue of John Singleton Copley in Copley Square with Hancock Tower and Trinity Church

Famed Trinity (Episcopal) Church, on Copley Square

The fountain at Copley Square

— Photo by Eric Friedebach

Farmers market at Copley Square

— Photo by Caroline Culler (User:Wgreaves)

Lightly edited from a Boston Guardian article. Second picture from the top is from The Guardian.

(Full disclosure, New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

The unfinished renovation of Copley Square Park, in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood, which has been ongoing since 2023, has already been met with mixed reviews from residents. Copley Square is Boston’s most famous square.

The project was originally slated to be completed by the end of 2024, but the city extended the deadline to April 2025, anticipating the Boston Marathon.

The deadline has since been extended to September, and subsequently to the end of 2025. The current budget sits at $18.9 million, more than double the original estimated budget of $7.5 million in 2021.

“It’s premature to jump to definitive conclusions until we see the definitive outcome,” said Martyn Roetter, chairman of the Neighborhood Association of the Back Bay, which was involved in the planning of the Copley Square redesign.

“The mayor said that this design is a result of endless numbers of community engagements and questions and surveys, which is kind of true. However, I can confirm that certainly NABB was opposed to this particular design. We would’ve preferred much more of a repair and restore operation.”

The opened section of the park currently features a wide concrete “event space,” as described on the project webpage of Sasaki, the consulting firm hired to complete the redesign.

“We did not have a space for public gatherings, like a block party, or the Boston Marathon setup, or the farmer’s market, or different demonstrations,” said Meg Mainzer-Cohen, the president of the Back Bay Association. Any events hosted on the grass at Copley, or along the Commonwealth Ave. Mall, she said, caused a lot of harm to the grass and were not sustainable.

“The plans for Copley Square had to do with having more hardscape, so that the city could host different events that would not do any harm to the grass. I did have the opportunity, when the farmer’s market moved into the new park, to really notice how well that works. I think it’s really creating a great public space.”

But residents are still unsure about having events be the focus of the space. “We don’t want it to turn into a smaller version of City Hall Plaza,” Roetter said. Sasaki, the consulting firm, also redesigned City Hall Plaza, which completed construction in 2022.

The city has also opened the “raised grove” section to the left of the plaza in Copley Square, which is a slightly higher gray concrete space that houses 10 trees and wooden benches along the sides.

The rest of the park, which is still blocked off, will include a small lawn in front of Trinity Church, and concrete paths cutting diagonally across to streamline foot traffic. The original Copley Square Plaza fountain will be preserved.

“Many residents and visitors have expressed appreciation for how the space is functioning,” a spokesperson for the Parks Department said in an email, pointing specifically to the success of the farmer’s market. “At the same time, some community members have shared that they’d like to see more green space in the park. We hear and value that feedback, and we’re excited that the final phase of the project, which includes an expanded lawn area near Trinity Church and the renovation of the iconic fountain, will directly address that need.”

Drawn back to the light, etc.

Androscoggin River, with the Free-Black railroad bridge in the foreground, in Brunswick, Maine.

— Photo by Jules Verne Times Two

“I'm drawn to New England because that's where my roots are, and I miss it. I come from many generations of New Englanders, and so, in my writing, I've been drawn back there to the landscape and the light and the type of personality that's revealed.’’

Elizabeth Strout (born 1956), a celebrated novelist, is a Maine native who divides her time between New York City and Brunswick. Much of her work is set in The Pine Tree State.

Making sense of life

“Let Me See” (acrylic on wood), by Elsa Campbell, in her show “The Art of Letting Go,’’ at the Atlantic Works Gallery East Boston, through May 31.

She says:

“I am inspired by color, line and shape using imagery that comes from my imagination based on events in my life. Art is how I make sense of life, portraying an inner landscape of the emotions, reactions and awareness of what it is to be a feeling person in the world.’’

‘Sparse, sincere rebellion’

U.S. World War I poster, 1917-18.

“On a thousand small town New England greens,

the old white churches hold their air

of sparse, sincere rebellion; frayed flags

quilt the graveyards of the Grand Army of the Republic.’’

—From “For the Union Dead,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977)