After black fly season?

“Mount Katahdin from the West Branch of the Penobscot” (1870) (oil on canvas), by Virgil Williams, in the current show “Some American Stories,’’ at the Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine.

— Photo: Peter Siegel, Pillar Digital Imaging LLC.

The show displays art from before the American Revolution to the present day.

Show-biz celebrities take over commencements

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal 24.com

Many colleges and universities hire show-business and sports figures (and professional sports are part of show biz) much more than, say, scholars to give commencement addresses. I suppose this is to get more publicity to the schools, but it diverts attention from what you’d think would be the institutions’ main mission – the rigorous creation and teaching of knowledge.

My undergraduate alma mater, Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H., is a prime example of this obsession with celebrity culture. It has had the likes of Shonda Rimes, Connie Britton, Conan O’Brien, Jake Tapper and sainted tennis legend Roger Federer as recent commencement speakers. This year it will be Sandra Oh, who is, I am told, a famous Canadian-American actress but a mystery to me. But then, our MAGA Master owes his political success to being a “reality TV” star on the absurd but very popular-in-the-Heartland TV show The Apprentice.

One thinks yet again of Neil Postman’s classic book Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

The commencement speakers used to be mostly the likes of foreign or U.S. government leaders, diplomats, academics, including celebrated scholars and college presidents, statesmanlike corporate leaders, and philanthropists. Consider that the speaker in 1970, when I got my degree, was the classicist William Arrowsmith, who very briefly mentioned Vietnam. But higher culture doesn’t pack ‘em in.

Familiar scenes in a new light

“Armistad Pier, New London, Connecticut” (silver gelatin print), by William Earle Williams, in his show “Their Kindred Earth,’’ at the Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Conn., through June 22.

— Photo courtesy of Mr. Williams

The museum says:

“Williams’s poignant images make visible little-known sites significant to enslavement, emancipation, and African Americans’ contributions to Connecticut history and culture. The photos prompt viewers to consider familiar landscapes in a new light and to imagine, perhaps for the first time, what life was like for enslaved people in Connecticut 200 years ago.’’

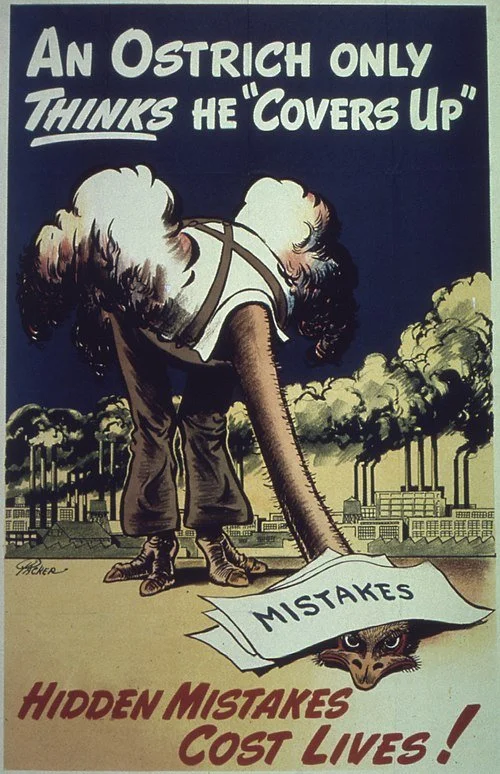

Chris Powell: Hiding police misconduct; inappropriate flags at public buildings

MANCHESTER, Conn.

State government's retreat from accountability for its employees and municipal employees is continuing, as legislation that would conceal accusations of misconduct against police officers is working its way through the General Assembly without any critical reflection by legislators.

The bill, publicized by Connecticut Inside Investigator's Katherine Revello, was approved unanimously by the Senate and would prohibit the release of complaints of misconduct against officers prior to any formal adjudication of the complaints by police management.

Of course that's an invitation to police agencies to conceal all complaints of misconduct and delay formal adjudication of them.

Yes, there can be false or misleading complaints against officers, and maybe disclosure of such complaints will unfairly harm some officer's reputation someday. But the chances of that are small. News organizations aren't likely to publicize such complaints without doing some investigation themselves, and the local news business is withering away.

But police misconduct is always being covered up somewhere, Connecticut has a long record of it, going back to the murder of the Perkins brothers by four state troopers in Norwich in 1969, and chances that government will strive to conceal its mistakes and wrongdoing are always high, just as the chances that the state Board of Mediation and Arbitration will nullify any serious discipline for government employees are always high.

Testifying against the secrecy legislation, former South Windsor Police Chief Matthew Reed, now a lawyer for the state Freedom of Information Commission, noted that the bill would impair the high standards Connecticut purports to want in police work. Reed cited the state law that prohibits municipal police departments from hiring any former officer who resigned or retired while under investigation. If such investigations are kept secret, that law may become useless.

Government employees in Connecticut are always seeking exemption from the scrutiny guaranteed by the state's freedom-of-information law, and imposing secrecy on complaints against police is likely to lead to requests from other groups of government employees for similar exemptions.

Even the state senators from districts with large minority populations who have supported police- accountability legislation in the past seem to have given the complaint-secrecy bill a pass. Maybe they are tired of being criticized as anti-police when they are really pro-accountability. Will there be enough pro-accountability members of the House of Representatives to stop the cover-up enabling act?

“Pride’’ flags like this shouldn’t go up at public buildings.

To help save it from itself, Connecticut could use a few more gadflies like T. Chaz Stevens, a Florida resident who used to live in Shelton, Conn., and who keeps an eye out for government's excessive entanglement with religion.

Stevens is the founder of what he calls the Church of Satanology and Perpetual Soirée, and the other day he scolded the Hartford City Council for having flown a Christian religion flag at City Hall in April. In response Stevens wrote to Mayor Arunan Arulampalam asking that City Hall also fly the flag of his church, thereby complying with the 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision holding that if government buildings grant requests to fly non-government flags, they have to grant all such requests, lest they violate First Amendment rights.

If Stevens's request is denied, he could sue and well might win.

The Hartford Courant reports that two members of the Hartford City Council, Joshua Michtom and John Gale, both lawyers, saw this problem coming and voted against flying the Christian flag. Other cities in Connecticut recently have made the same mistake by flying a Christian flag on government flagpoles: Bridgeport, New Britain, Torrington and Waterbury.

No matter how the U.S. Constitution is construed, government flagpoles should be restricted to government flags, which represent everyone. Anything else lets the government be propagandized by groups with political influence. That is especially the case with the continuing efforts around the state to fly the “Pride’’ flag on government flagpoles.

The national and state flags already represent freedom of sexual orientation. But the “Pride" flag is construed to represent letting men into women's restrooms, sports, and prisons, politically correct silliness about which there is sharp division of opinion.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

17th Century hysteria

From the show “Witch Panic!: Massachusetts Before Salem’’ (witch trials), at the Springfield (Mass.) Museums through Nov. 2

The curator writes:

“Discover a time when people accused of being witches walked among us. Forty years before the infamous trials in Salem, fear gripped the small settlement of Springfield, Massachusetts. Neighbors whispered about Mary and Hugh Parsons as rumors simmered for years, exploding into hysteria that eventually consumed the town. Witch Panic! dives into the daily lives of the Parsons, examining the circumstances that led to their 1651 accusation and arrest for witchcraft.

“Learn about the folklore surrounding witches, like their association with broomsticks, black cats, and cauldrons, or design your own ghoulish familiar, a small creature believed to help witches.’’

A bit of Iowa

Connecticut Valley in Sunderland, Mass., looking south toward Amherst (high buildings at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

— Photo by enFrantzDale

“Between Amherst and the Connecticut River lies a little bit of Iowa — some of New England’s more favored farmland. The summer and fall of 1982, Judith bicycled, alone and with Jonathan, down narrow roads between field of asparagus and corn, and she saw the constructed landscape with new eyes, not just looking at houses but searching for ones that might serve as models for her own. She liked the old farmhouses best, their porches and white clapboarded walls.’’

— From House (1982), by Tracy Kidder

Most educated, but might drown

Harvard master's degree gowns

Edited from a Boston Guardian report.

The ZIP code in America with the highest percentage of highly educated people?

If you guessed any of the ZIP codes associated with Harvard or MIT, you guessed wrong.

According to data recently published in The Boston Business Journal, the country’s most educated ZIP code is 02210, which encompasses the Seaport district. 93 percent of its residents have a college degree or higher.

In terms of bright ZIP codes in Massachusetts, the Seaport is followed by:

• Wellesley Hills (02481)

• Waban (02468)

• Newton Highlands (02461)

• Lincoln (01773)

• Dover (02030)

• Brookline (02445)

• Cambridge (02138)

• Lexington (02420)

• Lexington (02421).

Other Boston ZIP codes on the list are 02215 (Fenway/Kenmore Square) at number 11, 02114 (Beacon Hill/West End) at 18 and 02113 (North End) at 24.

If you live anywhere else, study harder.

Speaking to fantasies about under-represented cultures

“CONERICOT” (paper, cardboard and glue, by Justin Favela, in his show “Do You See What I See?’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, through June 22.

The curator explains:

“Brilliant colors, tissue paper, cardboard, and untold stories converge in “Do You See What I See?’’ Nestled throughout the galleries, this exhibition is an exploration of the artist's quest to see himself and the vibrant Latinx community represented within the museum's esteemed collection.

“CONERICOT,’’ Favela’s piñata-inspired mural, draws inspiration from depictions of Latin America from the permanent collection. His immersive installation alludes to the beauty of those landscapes, as well as the fantasies that often color Americans' perceptions of these under-represented cultures.’’

‘For one song more’

Wood Thrush

As I came to the edge of the woods,

Thrush music — hark!

Now if it was dusk outside,

Inside it was dark.

Too dark in the woods for a bird

By sleight of wing

To better its perch for the night,

Though it still could sing.

The last of the light of the sun

That had died in the west

Still lived for one song more

In a thrush's breast.

Far in the pillared dark

Thrush music went —

Almost like a call to come in

To the dark and lament.

But no, I was out for stars;

I would not come in.

I meant not even if asked;

And I hadn't been.

“Come In,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Sneaking ‘under the heavy door of learning’

Bronze statue of Dr. Seuss and his character “The Cat in the Hat” outside the Geisel Library at the University of California at San Diego.

Ad done by the author and artist who became the famous Dr. Seuss that ran in the July 14, 2028 issue of The New Yorker.

“Dr Seuss, the creation and the creator, was unlike most adults. He remembered. He retained a sense of the absurd, including the absurdity of the idea that growing up means losing your humor. So, while too many adults spend their time teaching children the seriousness of the situation, he managed to sneak under the heavy door of learning, asking, “Do you like green eggs and ham?”

— Columnist Ellen Goodman (born 1941), on Theodor Seuss Geisel (1904-1991), aka Dr. Seuss. He grew up in Springfield, Mass., and graduated from Dartmouth College.

—

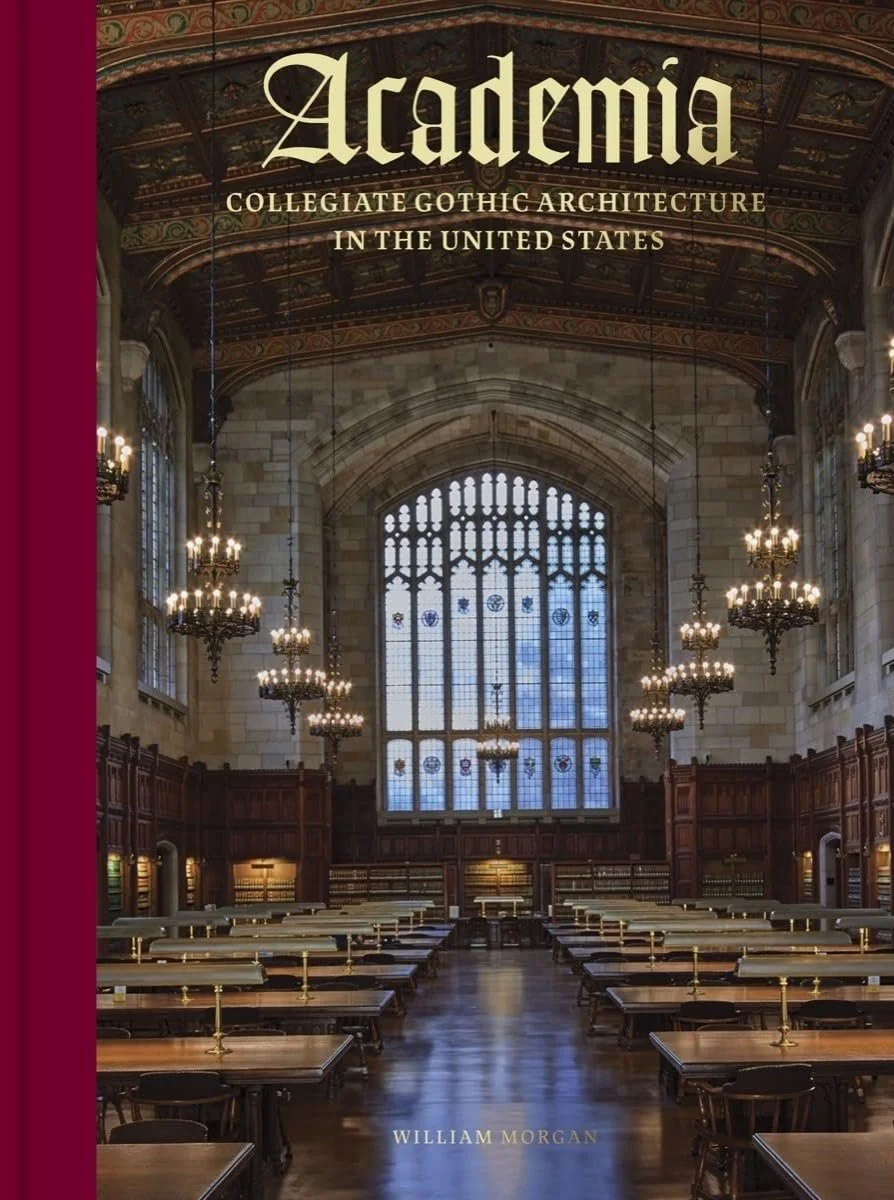

Robert Whitcomb: Morgan’s book says a lot about America

This first appeared in GoLocal24.com

“Americans are the only people in the world known to me whose status anxiety prompts them to advertise their college and university affiliations on the rear window of their automobiles.’’

-- Paul Fussell (1924-2012), American historian

In reading William Morgan’s brilliantly written and gorgeously illustrated new book, Academia – Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, you might recall Winston Churchill’s famous line: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.’’

I thought of this looking back at an institution I attended, a then-all-boys boarding school in Connecticut called The Taft School, founded by Horace Taft, the brother of President William Howard Taft. Its mostly Collegiate Gothic buildings made some of us students feel we were in a hybrid of a medieval church and a fort. This, I think, encouraged a certain personal rigor and seriousness of purpose, amidst the usual adolescent cynicism and jokiness.

The style originally reflected a certain Anglophilia embraced by some American nouveau riche as they accumulated fortunes in a rapidly expanding economy. Rich donors, and the institutional architects they got hired, wanted to create buildings evoking kind of elite, aristocratic culture at certain old Protestant colleges and universities and private boarding schools. (Many of the latter were modeled on English boarding schools catering to the aristocracy.) There was often a lot of snobbery involved. But the style spread to other institutions, too, including businesses and government offices, around the country.

Some of this included fantastical (to the point of silliness) ornamentation and instant aging of stonework to suggest the wear of centuries on what were brand-new buildings, perhaps most flamboyantly at Yale. Get out those gargoyles!

This book is about much more than architecture. It’s also about personalities, many of them colorful, class, including social climbing, economics, politics and many other things.

One of the book’s joys is Mr. Morgan’s footnotes, which besides adding to the understanding of the main text, are often very entertaining, sometimes even hilarious.

Robert Whitcomb is editor of New England Diary.

Tragic and frequent

“The Tragedy of War,’’ by Craig Masten. The painting won the New England Watercolor Society’s first prize in the organization’s 2023 New England Regional Exhibition.

Two business questions

Centreville Bank Stadium in early 2025, shortly before construction was completed.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

A question about the new Centreville Bank Stadium, in Pawtucket, home of the Rhode Island FC soccer team, is whether that it was sold out on May 3, for the team’s first home match, suggests that it will be a long-term success. Or were many of the about 10,700 attendees mostly there out of curiosity to see the pretty place, which will cost Rhode Island taxpayers around $132 million over 30 years? Americans’ increasing interest in the nearest thing to the world sport will help, but the seats are expensive – from $34 to $436 -- and baseball, football and basketball are deeply embedded in the national psyche.

Hasbro’s notably unpretentious headquarters, in the old mill town of Pawtucket.

Poor Hasbro, with so much of its manufacturing in China, has its hands full trying to adapt to Trump’s volatile tariff policies. Executives of the toy and entertainment giant hope to be making fewer than 40 percent of its products in China by 2026, down from about 50 percent now. It will not be moving much manufacturing to the U.S., but rather will seek cheap labor and special favors in other Asian nations or maybe in Africa or Latin America.

A big question in Rhode Island is whether the cost of the tariff trauma will lead Hasbro to decide not to move to Boston but rather to stay in Rhode Island, where most costs are cheaper and there are many designers, in part because of RISD. To get it to stay, will state politicians promise it tax and other incentives that would deplete those that could be offered to smaller companies to stay in, or move to, the Ocean State?

UVM researchers strive to reduce honeybee mortality

Beekeeper at work

— Photo by Ich -

“Skep Sisters” (encaustic painting), by Nancy Whitcomb.

Edited from a New England Council report

“The University of Vermont recently released a study offering hope for stemming the recent debilitating losses of bees in the country and suggestions for breeding more disease-resistant colonies. Beekeepers across the U.S. lost over 55 percent of their colonies in the past year, the highest loss rate reported since records started being kept, in 2011.

“The Vermont Bee Lab at UVM, led by Samantha Alger, works with beekeepers to breed ‘hardy, disease-resistant’ honeybee colonies by using a test (UBeeO) developed by researchers at the University of North Caroline at Greensboro to help identify ‘hygienic’ behaviors in colonies….

“The Vermont Bee Lab found that the UBeeO testing method detects more pathogen loads than was previously thought, letting UVM researchers use the test to better analyze methods to encourage disease-resistant colonies.

“‘It’s definitely more desirable for a beekeeper to have bees that are better adapted at taking care of their diseases themselves rather than using chemical treatments and interventions to try to reduce these pathogen loads, which of course may have negative impacts on the bees. … UBeeO has been known to identify colonies that are able to better resist Varroa mites, but it had not been used to look at other pest or pathogens. We found this new assay could be used to identify colonies that are resistant to these other stressors,’ said Algers.’’

Mosaic master

From Sandra K. Basile’s (video) mosaic show at the Providence Art Club through May 29.

Rick Baldoz: The long history of America’s politically motivated deportations

Cartoon by Archibald B. Chapin in the South Bend News-Times of Nov. 8, 1919

From The Conversation, except for image above

Rick Baldoz is an associate professor of American Studies at Brown University.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations.

PROVIDENCE

The recent deportation orders targeting foreign students in the U.S. have prompted a heated debate about the legality of these actions. The Trump administration made no secret that many individuals were facing removal because of their pro-Palestinian advocacy.

In recent months, the State Department has revoked hundreds of visas of foreign students with little explanation. On April 25, 2025, the administration restored the legal status of many of those students, but warned that the reprieve was only temporary.

Because of their tenuous legal status in the U.S., immigrant activists are vulnerable to a government seeking to stifle dissent.

Critics of the Trump administration have challenged the legality of these removal orders, arguing that they violate constitutionally protected rights, including freedom of speech and due process.

The administration asserts that the executive branch has nearly absolute authority to remove immigrants. The White House has cited legislation passed during the peak of the nation’s Cold War hysteria, like the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952, which expanded the government’s deportation powers.

I’m a historian of immigration, U.S. empire and Asian American studies. The current removal orders targeting student activists echo America’s long and lamentable past of jailing and expelling immigrants because of their race or what they say or believe – or all three.

The arrest of Turkish graduate student Rümeysa Öztürk by Department of Homeland Security agents in Somerville, Mass., on March 25, 2025.

The United States’ current deportation process traces its roots to the late 19th century as the nation moved to exercise federal control of immigration.

The impetus for this shift was anti-Chinese racism, which reached a fever pitch during this period, culminating in the passage of laws that restricted Chinese immigration.

The influx of Chinese immigrants to the West Coast during the mid-to-late 19th century, initially fueled by the California Gold Rush, spurred the rise of an influential nativist movement that accused Chinese immigrants of stealing jobs. It also claimed that they posed a cultural threat to American society due to their racial otherness.

The Geary Act of 1892 required Chinese living in the U.S to register with the federal government or face deportation.

The Supreme Court addressed the constitutionality of these statutes in 1893 in the case of Fong Yue Ting v. United States. Three plaintiffs claimed that anti-Chinese legislation was discriminatory, violated constitutional protections prohibiting unreasonable search and seizure, and contravened due process and equal protection guarantees.

The Supreme Court affirmed the Geary Act’s deportation procedures, formulating a novel legal precept known as the plenary power doctrine that remains a key tenet of U.S. immigration law today.

Court confirms the law

The doctrine included two key assertions.

First, the federal government’s authority to exclude and deport aliens was an inherent and unqualified feature of American sovereignty. Second, immigration enforcement was the exclusive domain of the congressional and executive branches that were charged with protecting the nation from foreign threats.

The court also ruled that the deportation of immigrants in the country lawfully was a civil, rather than criminal matter, which meant that constitutional protections like due process did not apply.

The government ramped up deportations in the aftermath of World War I, fueled by wartime xenophobia. American officials singled out foreign-born radicals for deportation, accusing them of fomenting disloyalty.

The front page of the Ogden Standard, from Ogden City, Utah, on Nov. 8, 1919, announcing the arrest and planned deportation of ‘alien Reds.’ Library of Congress

Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, who ordered mass arrests of alleged communists, pledged to “tear out the radical seeds that have entangled Americans in their poisonous theories” and remove “alien criminals in this country who are directly responsible for spreading the unclean doctrines of Bolshevism.”

This period marked a new era of removals carried out primarily on ideological grounds. Jews and other immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were disproportionately targeted, highlighting the cultural affinities between anti-radicalism and racial and ethnic chauvinism.

‘Foreign’ agitators

The campaign to root out so-called subversives living in the United States reached its apex during the 1940s and 1950s, supercharged by figures like anti-communist crusader Sen. Joseph McCarthy and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

The specter of foreign agitators contaminating American political culture loomed large in these debates. Attorney General Tom Clark testified before Congress in 1950 that 91.4 percent of the Communist Party USA’s leadership were “either foreign stock or married to persons of foreign stock.”

Congress passed a series of laws during this period requiring that subversive organizations register with the government. They also expanded the executive branch’s power to deport individuals whose views were deemed “prejudicial to national security,” blurring the lines between punishing people for unlawful acts – such as espionage and bombings – and what the government considered unlawful beliefs, such as Communist Party membership.

While deporting foreign-born radicals had popular support, the banishment of immigrants for their political beliefs raised important constitutional questions.

Harry Bridges, a West Coast labor leader, and his daughter, Jacqueline, 14, as they listen to proceedings during Bridges’ deportation hearing in San Francisco in July 1939. Underwood Archives/Getty Images

Prosecution or persecution?

In a landmark case in 1945, Wixon v. Bridges, the Supreme Court did assert a check on the power of the executive branch to deport someone without a fair hearing.

The case involved Harry Bridges, Australian-born president of the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen’s Union. Bridges was a left-wing union leader who orchestrated a number of successful strikes on the West Coast. Under his leadership, the union also took progressive positions on civil rights and U.S. militarism.

The decision in the case hinged on whether the government could prove that Bridges had been a member of the Communist Party, which would have made him deportable under the Smith Act, which proscribed membership in the Communist Party.

Since no proof of Bridges’s membership existed, the government relied on dodgy witnesses and assertions that Bridges was aligned with the party because he shared some of its political positions. Accusations of “alignment” with controversial political organizations are similar to the charges made against foreign students currently at risk of deportation by the Trump administration.

The Supreme Court vacated Bridges’s deportation order, declaring that the government’s claim of “affiliation” with the Communist Party was too vaguely defined and amounted to guilt by association.

As the excesses and abuses of the McCarthy era came to light, they invited greater scrutiny about the dangers of unchecked executive power. Some of the more draconian statutes enacted during the Cold War, like the Smith Act, have been overhauled. The federal courts have toggled back and forth between narrow and liberal interpretations of the Constitution’s applicability to immigrants facing deportation – shifts that reflect competing visions of American nationhood and the boundaries of liberal democracy.

From union leaders to foreign students

There are some striking parallels between the throttling of civil liberties during the Cold War and President Trump’s crusade against foreign students exercising venerated democratic freedoms.

Foreign students appear to have replaced the immigrant union leaders of the 1950s as the targets of government repression. Presumptions of guilt based on hyperbolic claims of affiliation with the Communist Party have been replaced by allegations of alignment with Hamas.

As in the past, these invocations of national security offer the pretext for the government’s efforts to stifle dissent and to mandate political conformity.

Intersection of painting and ecology

“We Are Always Growning,’’ by Stephanie Manzi, in the group show “Spring 2025 Solo Exhibition,’’ at the Southern Vermont Arts Center, Manchester through June 22.

She says in her artist statement:

“As I paint, draw and collage, marks collide into bands of color and form that map, frame, measure, separate and merge disparate elements. Information is revealed and concealed into new configurations through processed based systems of repetition and recycling. In the studio, I grapple with concepts of landscape in relation to painting and eco-theory through environmental interaction. Within landscape and ecology, deeply imposed structures around nature create distance between ourselves and our understanding of the natural world. Painting can mirror the same distancing. It creates a window, an object, and conceptually separate pictorial space that can feel detached from the viewers reality. Therefore, the experience of painting and conversations within ecology are similar; both beautiful complex, dark and concerning, hopeful and light. My work straddles similar contradictions: permission and limitation, play and serious inquiry, accumulation and loss, structure and the unbound.

“As a painter, I exist in both worlds. I have no direct solutions, only recorded personal observations of my environments. My hope is that as the work continues to develop, my interest with the intersection of painting and ecology can create a space of conversation, joy, connection and inquiry.’’

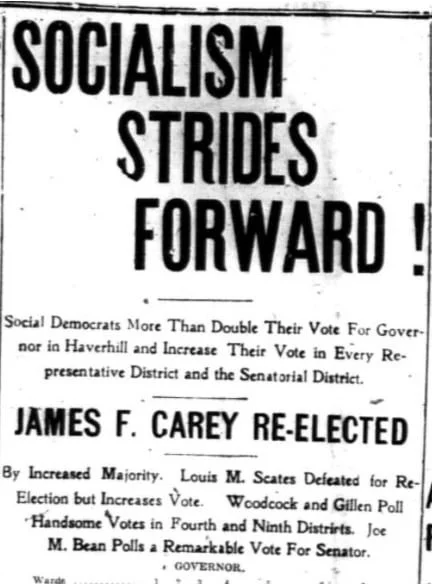

Haverhill’s socialist experiment

Text excerpted from Historic New England

The 1890s were turbulent years in New England—and Haverhill, Massachusetts, was no exception. Following the financial panic of 1893, the ‘Queen Slipper City’ quickly felt the effects of the national economic decline.

“At that time, Haverhill’s booming factories produced ten percent of the country’s shoes, employing a workforce of over 11,000 men and women engaged in cutting, stitching, lasting, trimming, and packing at over 230 factories. When the economy struggled, however, consumer demand for shoes decreased. An unexpected increase in the cost of leather cut further into profit margins, and employers quickly turned to several austerity measures to recoup their losses. They initiated a wave of lockouts, firings, and unfair ‘ironclad’ contracts while allowing working conditions to decline, leading to a massive general strike in 1895 in which over 3,000 shoe workers left the factories in protest.

“The strike was a warning for the local government. Haverhill’s workers wanted more for themselves and their families. They wanted better alignment with national unions, and they wanted the local government to recognize their needs more responsively.’’