So they came to us

View of Willoughby Notch and Mount Pisgah, in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom

“‘Away,’ most of us called anywhere more than five miles beyond the county line. Or ‘the other side of the hills.’ All I knew for certain is that since we could not go to them, the mind readers and barnstorming four-man baseball teams and one-elephant family circuses came to us.’’

— From the novel Northern Borders (1994), by Howard Frank Mosher (1942-2017), set in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, where Mosher lived in the town of Irasburg.

Lord's Creek Covered Bridge in Irasburg.

Faithslucas photo

Some very nice places if you can afford them

Providence neighborhoods

Providence City Council chambers.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

So Providence property taxes are going up this year. No surprise. And, especially with federal cutbacks, they might have to go up more in the next few years. The city last raised property taxes in fiscal 2023. Since then, of course, prices have continued to rise.

But Mayor Brett Smiley’s administration wants to mitigate the property-tax hike a bit by raising revenue on such things as parking and towing fines, animal mistreatment, liquor-license transfers and valet licenses. I suspect that one attraction of boosting parking fines is that the majority of the violators would be out-of-towners, not Providence voters.

Of course, locals and others will complain. But it seems to me that many user taxes are quite fair because they reflect personal decisions (and sometimes personal negligence). Still, I’m ambivalent about fees attached to doing business, such as liquor-license transfers and valet licenses. It can be mighty expensive to have a business in Providence.

Something that tends to be forgotten in the understandable complaints about sky-high housing prices in Providence. Whatever the city’s many flaws, lots of people like living here and many would like to move here, especially affluent folks eying the leafy East Side. That’s a reason that housing prices are so high, along with far too little housing construction.

Much of Providence’s tax revenue goes to its public schools – 37 percent for fiscal 2025. This leads to the thought, which I’ve expressed before, that its schools might be far better run if all of tiny Rhode Island’s 36 (!!) local school districts were abolished and replaced by regional districts or even just one statewide district to be managed by the best public-education executives the state could find. This could both improve the quality of schooling in communities, such as Providence, with many disadvantaged students, and save taxpayers a lot of money through economies of scale and elimination of duplicated services.

Of course this would mean a huge change in the Ocean State’s tax structure, wherein the state’s income and sales taxes would pay for most of public education. As it is, property taxes pay for over half of public-school costs.

Darius Tahir: Troubles multiply for Social Security recipients after Musk takes his chain saw to agency

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (KFFHealth News) (except for image above)

“The delayed payment is not something I’ve heard in the last 20 years.”

— Carolyn Villers, executive director of the Massachusetts Senior Action Council

Rennie Glasgow, who has served 15 years at the Social Security Administration, is seeing something new on the job: dead people.

They’re not really dead, of course. In four instances over the past few weeks, he told KFF Health News, his Schenectady, New York, office has seen people come in for whom “there is no information on the record, just that they are dead.” So employees have to “resurrect” them — affirm that they’re living, so they can receive their benefits.

Revivals were “sporadic” before, and there’s been an uptick in such cases across upstate New York, said Glasgow. He is also an official with the American Federation of Government Employees, the union that represented 42,000 Social Security employees just before the start of President Donald Trump’s second term.

Martin O’Malley, who led the Social Security Administration toward the end of the Joe Biden administration, said in an interview that he had heard similar stories during a recent town hall in Racine, Wisconsin. “In that room of 200 people, two people raised their hands and said they each had a friend who was wrongly marked as deceased when they’re very much alive,” he said.

It’s more than just an inconvenience, because other institutions rely on Social Security numbers to do business, Glasgow said. Being declared dead “impacts their bank account. This impacts their insurance. This impacts their ability to work. This impacts their ability to get anything done in society.”

“They are terminating people’s financial lives,” O’Malley said.

Though it’s just one of the things advocates and lawyers worry about, these erroneous deaths come after a pair of initiatives from new leadership at the SSA to alter or update its databases of the living and the dead.

Holders of millions of Social Security numbers have been marked as deceased. Separately, according to The Washington Post and The New York Times, thousands of numbers belonging to immigrants have been purged, cutting them off from banks and commerce, in an effort to encourage these people to “self-deport.”

Glasgow said SSA employees received an agency email in April about the purge, instructing them how to resurrect beneficiaries wrongly marked dead. “Why don’t you just do due diligence to make sure what you’re doing in the first place is correct?” he said.

The incorrectly marked deaths are just a piece of the Trump administration’s crash program purporting to root out fraud, modernize technology, and secure the program’s future.

But KFF Health News’ interviews with more than a dozen beneficiaries, advocates, lawyers, current and former employees, and lawmakers suggest the overhaul is making the agency worse at its primary job: sending checks to seniors, orphans, widows, and those with disabilities.

Philadelphian Lisa Seda, who has cancer, has been struggling for weeks to sort out her 24-year-old niece’s difficulties with Social Security’s disability-insurance. There are two problems: first, trying to change her niece’s address; second, trying to figure out why the program is deducting roughly $400 a month for Medicare premiums, when her disability lawyer — whose firm has a policy against speaking on the record — believes they could be zero.

Since March, sometimes Social Security has direct-deposited payments to her niece’s bank account and other times mailed checks to her old address. Attempting to sort that out has been a morass of long phone calls on hold and in-person trips seeking an appointment.

Before 2025, getting the agency to process changes was usually straightforward, her lawyer said. Not anymore.

The need is dire. If the agency halts the niece’s disability payments, “then she will be homeless,” Seda recalled telling an agency employee. “I don’t know if I’m going to survive this cancer or not, but there is nobody else to help her.”

Some of the problems are technological. According to whistleblower information provided to Democrats on the House Oversight Committee, the agency’s efforts to process certain data have been failing more frequently. When that happens, “it can delay or even stop payments to Social Security recipients,” the committee recently told the agency’s inspector general.

While tech experts and former Social Security officials warn about the potential for a complete system crash, day-to-day decay can be an insidious and serious problem, said Kathleen Romig, formerly of the Social Security Administration and its advisory board and currently the director of Social Security and disability policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Beneficiaries could struggle to get appointments or the money they’re owed, she said.

For its more than 70 million beneficiaries nationwide, Social Security is crucial. More than a third of recipients said they wouldn’t be able to afford necessities if the checks stopped coming, according to National Academy of Social Insurance survey results published in January.

Advocates and lawyers say lately Social Security is failing to deliver, to a degree that’s nearly unprecedented in their experience.

Carolyn Villers, executive director of the Massachusetts Senior Action Council, said two of her members’ March payments were several days late. “For one member that meant not being able to pay rent on time,” she said. “The delayed payment is not something I’ve heard in the last 20 years.”

When KFF Health News presented the agency with questions, Social Security officials passed them off to the White House. White House spokesperson Elizabeth Huston referred to Trump’s “resounding mandate” to make government more efficient.

“He has promised to protect Social Security, and every recipient will continue to receive their benefits,” Huston said in an email. She did not provide specific, on-the-record responses to questions.

Complaints about missed payments are mushrooming. The Arizona attorney general’s office had received approximately 40 complaints related to delayed or disrupted payments by early April, spokesperson Richie Taylor told KFF Health News.

A Connecticut agency assisting people on Medicare said complaints related to Social Security — which often helps administer payments and enroll patients in the government insurance program primarily for those over age 65 — had nearly doubled in March compared with last year.

Lawyers representing beneficiaries say that, while the historically underfunded agency has always had its share of errors and inefficiencies, it’s getting worse as experienced employees have been let go.

“We’re seeing more mistakes being made,” said James Ratchford, a lawyer in West Virginia with 17 years’ experience representing Social Security beneficiaries. “We’re seeing more things get dropped.”

What gets dropped, sometimes, are records of basic transactions. Kim Beavers of Independence, Missouri, tried to complete a periodic ritual in February: filling out a disability update form saying she remains unable to work. But her scheduled payments in March and April didn’t show.

She got an in-person appointment to untangle the problem — only to be told there was no record of her submission, despite her showing printouts of the relevant documents to the agency representative. Beavers has a new appointment scheduled for May, she said.

Social Security employees frequently cite missing records to explain their inability to solve problems when they meet with lawyers and beneficiaries. A disability lawyer whose firm’s policy does not allow them to be named had a particularly puzzling case: One client, a longtime Social Security disability recipient, had her benefits reassessed. After winning on appeal, the lawyer went back to the agency to have the payments restored — the recipient had been going without since February. But there was nothing there.

“To be told they’ve never been paid benefits before is just chaos, right? Unconditional chaos,” the lawyer said.

Researchers and lawyers say they have a suspicion about what’s behind the problems at Social Security: the Elon Musk-led effort to revamp the agency.

Some 7,000 SSA employees have reportedly been let go; O’Malley has estimated that 3,000 more would leave the agency. “As the workloads go up, the demoralization becomes deeper, and people burn out and leave,” he predicted in an April hearing held by House Democrats.

“It’s going to mean that if you go to a field office, you’re going to see a heck of a lot more empty, closed windows.”

The departures have hit the agency’s regional payment centers hard. These centers help process and adjudicate some cases. It’s the type of behind-the-scenes work in which “the problems surface first,” Romig said. But if the staff doesn’t have enough time, “those things languish.”

Languishing can mean, in some cases, getting dropped by important programs like Medicare. Social Security often automatically deducts premiums, or otherwise administers payments, for the health program.

Lately, Melanie Lambert, a senior advocate at the Center for Medicare Advocacy, has seen an increasing number of cases in which the agency determines beneficiaries owe money to Medicare. The cash is sent to the payment centers, she said. And the checks “just sit there.”

Beneficiaries lose Medicare, and “those terminations also tend to happen sooner than they should, based on Social Security’s own rules,” putting people into a bureaucratic maze, Lambert said.

Employees’ technology is more often on the fritz. “There’s issues every single day with our system. Every day, at a certain time, our system would go down automatically,” said Glasgow, of Social Security’s Schenectady office. Those problems began in mid-March, he said.

The new problems leave Glasgow suspecting the worst. “It’s more work for less bodies, which will eventually hype up the inefficiency of our job and make us, make the agency, look as though it’s underperforming, and then a closer step to the privatization of the agency,” he said.

Darius Tahir is a KFF Health News reporter.

Darius Tahir: DariusT@kff

Jodie Fleischer of Cox Media Group contributed to this report.

New England Council starts summer fellowship program

Flag adopted by the New England Governors Association as the region’s semi-0fficial flag.

Edited from a New England Council report

“The New England Council, the nation’s oldest regional business association, has selected six non-profit organizations – one in each New England state – to host the inaugural class of New England Council Fellows during the summer of 2025. The New England Council Fellows program was established to commemorate the 100th Anniversary of the Council’s founding.

“Under the program, the six organizations selected will each receive $5,000 to support the hiring of a summer intern to support their charitable mission. The goals of the program are twofold: to support worthy organizations with missions to provide important services in the region, and to help provide young adults with valuable work experience to prepare them for future career success. In the coming weeks, these six organizations will select young adults who will serve as New England Council fellows summer.

“The six organizations selected to host New England Council Fellows are:

Connecticut: Connecticut Foodshare – Connecticut Foodshare, a member of the national Feeding America network and the primary food bank serving the entire state, works to deliver a more informed and equitable response to hunger by mobilizing community partners, volunteers, and supporters throughout Connecticut. The food bank operates collaboratively through a network of 650 hunger-relief partners to provide immediate access to healthy and nutritious food to the nearly 470,000 food-insecure people in Connecticut. The food bank employs a SNAP application assistance team to help people apply for benefits, visit ctfoodshare.org/SNAP to learn more.

Maine: Dempsey Centers for Quality Cancer Care – The Dempsey Center was founded by actor, Patrick Dempsey, in 2008 after his mother’s experience with cancer and as a way to give back to his hometown community of Lewiston, Maine. Recognizing that a cancer diagnosis extends beyond the patients, their programs provide a wide range of holistic support that address the physical, functional, social, and emotional well-being of anyone impacted by cancer. Services are offered at completely no cost and include counseling, nutrition, movement + fitness, bodywork therapies, and more. Today, the Dempsey Center has grown to two locations in Lewiston and Westbrook, Maine, a hospitality home in Portland, Maine, and has adapted to providing robust support to clients virtually via Dempsey Connects.

Massachusetts: St. Mary’s Center for Women and Children – St. Mary’s Center for Women and Children, a multi-service organization supporting 500 women, children, and families annually, believes shelter is not enough to erase the devastation of cyclical poverty and homelessness. Grounded in social justice, St. Mary’s Center empowers families to achieve emotional stability and economic independence through education, workforce development, behavioral health and family medicine, and permanent housing. Founded in 1993, St. Mary’s Center offers a series of residential programs and wrap-around support services across the housing continuum for families experiencing homelessness. Through evidence-based best practice and an integrated model of care, St. Mary’s Center works to ensure those most vulnerable not only secure, but maintain, housing to establish long-term stability, breaking cycles of multi-generational poverty and establishing two generations of stable futures.

New Hampshire: United South End Settlements’ Camp Hale – United South End Settlements’ (USES) mission is to harness the power of our diverse community to disrupt the cycle of poverty for children and families. Camp Hale, USES’s cornerstone program since 1900, empowers underserved youth through transformative outdoor experiences. Located on Squam Lake in Sandwich, NH, Camp Hale offers youth the opportunity to experience a sleepaway camp in the natural beauty of the White Mountains. Camp Hale serves 225+ boys and girls each summer, ages 5-18+ years, with the goal of increasing their sense of well-being, independence, and leadership skills.

Rhode Island: Pawtucket Central Falls Development – Pawtucket Central Falls Development (PCF Development) is a community development organization focused on housing and financial education. It aims to provide affordable rental and homeownership housing and educational resources, with a commitment to community empowerment and equity. Through a community central approach, it works to improve the physical infrastructure of the neighborhood while providing financial education for residents to create sustainable, accessible opportunities, primarily focusing on lower income individuals and families.

Vermont: US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants – The U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI) was established in 1911 and is a nongovernmental, not-for-profit international organization dedicated to addressing the needs and rights of refugees and immigrants. The USCRI Field Office in Vermont has been welcoming newcomers to Vermont since 1980. Our dedicated team of staff, volunteers, and community partners supports these refugees and immigrants with access to affordable housing, medical and mental health support, education, employment, community connections, and more. Refugees resettled in Vermont come primarily from Afghanistan, Bhutan, Bosnia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Iraq, Russia, Somalia, Syria, and Ukraine.

“‘Each of these six organizations serves a vital mission in our region, supporting some of the most vulnerable members of our society and providing much needed services to a variety of constituencies, and we are proud to be able to support their work as the Council celebrates our centennial,’ said James T. Brett, New England Council president and CEO. ‘At the same time, these fellowships will provide young adults in the region with valuable hands-on work experience that will prepare them for success in our region’s workforce.’’’

‘Duppies’ in Greenwich

In sculptor Nickola Pottinger’s show, ‘‘fos born,’’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Greenwich, Conn., through Jan. 11, 2026.

The museum says:

“Nickola Pottinger’s practice spans drawing, collage, and sculpture. Her objects often appear in the round, on the wall, or sometimes within tableaux. She refers to her sculptural works as ‘duppies’ (Jamaican patois for ghosts) in reverence to her Jamaican ancestry and the West Indian community in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, where she was raised and still resides today. Composed out of recovered heirlooms, excavated and recycled materials, Pottinger creates pigmented paper pulp from family documents, past artworks, and rubble using a handheld kitchen mixer.’’

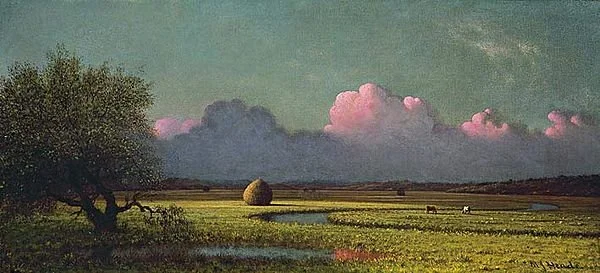

Back to the marshes

“Sunlight and Shadow: The Newbury (Mass.) Marshes” (oil on canvas), by Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904).

'Tis May now in New England

And through the open door

I see the creamy breakers,

I hear the hollow roar.

Back to the golden marshes

Comes summer at full tide,

But not the golden comrade

Who was the summer's pride.

— “Tis May Now in New England,’’ by Bliss Carman (1861-1929), Canadian poet who lived most of his life in the United States.

Sincerity demanded?

“New England is different; its literature is different. For instance, it is an American trait not to be as sensitive, socially and culturally, as New England is. Yankees are terrified of being snubbed or, worse, patronized. Sincerity is not merely appreciated, it is demanded. In a famous example given I think by {historian} Bernard DeVoto, the lost tourist leans from his car window and says, with the gruffness, possibly, of embarrassment, ‘I want to get to St. Johnsbury! {Vt.}’

“After a pause, one of the men sitting on the {general} store steps says, mildly, ‘We’ve no objection.’’’

— From Thomas Williams’s forward to New Fiction from New England (1986)

Beasts abound

Copy of English map of the Piscataqua River; on the border of Maine and New Hampshire, c. 1670

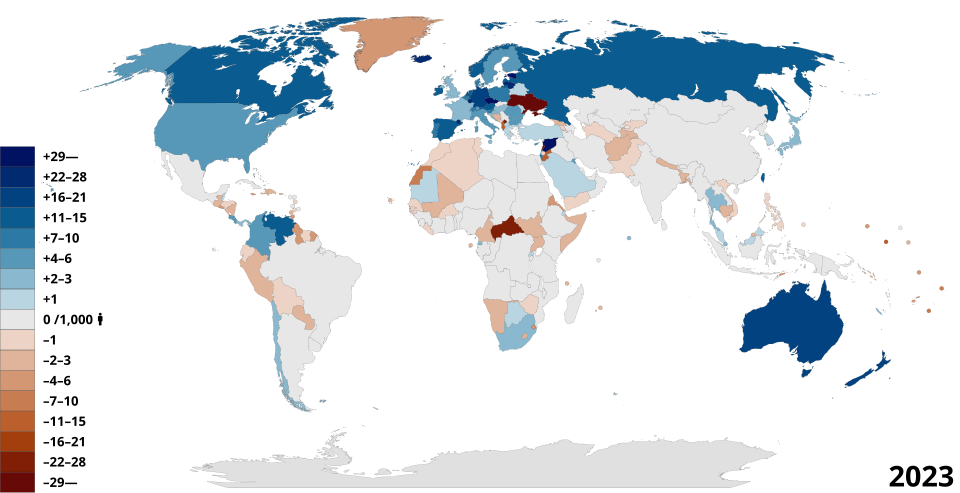

Chris Powell: Illegal-immigration backers ignore its enormous costs

Net migration rates per 1,000 people in 2023, showing flows to more affluent nations, in blue, from poorer nations.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Last week two groups supporting illegal immigration, Connecticut Voices for Children and the Immigration Research Initiative, issued a report warning that mass deportation of the state's illegal-immigrant population -- estimated at as many as 150,000 people -- would be disastrous for the state's economy and state government. The report claimed that illegal immigrants pay more than $400 million in state taxes each year.

This was at best a dodgy estimate. Many illegal immigrants are children and are not employed. The adults among them cannot work legally and so most of their earnings cannot be tracked. While anyone who spends money in Connecticut is likely to pay sales taxes, the report acknowledges that nearly all illegal immigrants who work in Connecticut hold low-wage jobs.

So what they buy is mainly for subsistence, like food, which is exempt from sales tax.

But the bigger flaw in the report is that it omits anything about the costs of illegal immigration in Connecticut, which are huge and increasing, particularly on account of the state government medical insurance being extended to them and the education of their children, most of whom don't speak English and enter the state's schools without providing any record of their education elsewhere and so need to be laboriously evaluated for placement. These students have exploded expenses in the schools of Connecticut's “sanctuary cities," which in turn seek much more financial support from state government.

In February the Yankee Institute, drawing on estimates from the Federation for American Immigration Reform, contended that illegal immigration costs Connecticut more than $1 billion a year.

Whatever the true cost, that it likely weighs heavily against illegal immigration became clear when Governor Lamont, a supporter of the state's “sanctuary’’ policies, disputed the Yankee Institute estimate even as he conceded to a journalist that he had no idea what illegal immigrants cost state government. The governor referred the journalist to the state budget office, which said it had no idea of the cost either and wasn't going to find out.

That is, advocates and apologists for illegal immigration in Connecticut don't want to know its costs, and, worse, don't want the public to know either.

The report from Connecticut Voices for Children and the Immigration Research Initiative is defective in other ways. It asserts that if Connecticut lacked illegal immigrants it would experience a severe shortage of workers for the low-wage jobs they hold -- especially in construction, restaurants, agriculture, janitorial work, and beauty shops.

This is the cliche that illegal immigrants do jobs citizens won't do, and it is nonsense.

Citizens will do almost any job if wages are high enough and can compete with the welfare benefits available to them. Indeed, the jobs held by illegal immigrants are so poorly paid in large part precisely because illegal immigrants are available to do them without the wage,

benefit and labor protections required for citizens. Raise agricultural salaries enough and even some teachers, charity organization workers, and journalists in Connecticut may be tempted to return to picking shade tobacco as many did as teenagers.

Connecticut is full of low-skilled citizen labor. With its social-promotion policy, public education makes sure of that.

For years the state's manufacturers have lamented that they can't find skilled workers for tens of thousands of openings. Meanwhile, middle-aged single mothers are not working at fast-food drive-through windows because they are so highly skilled. But jobs requiring lesser skills are where young people are supposed to start, not remain as adults.

So Connecticut doesn't need to import more low-skilled workers, especially since the state has failed so badly with its housing supply. The state needs to find ways of raising skills and wages and reducing the cost of living, especially the cost of housing, for its legal residents.

But the report from the apologists for illegal immigration sees the path to prosperity as a matter of legalizing all illegal immigrants, in effect reopening the borders. It didn't work the first time.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Nature in Your Dreams

Pastel by Steve Chase, in show “Steve Chase: A Singular Vision,’’ at Ava Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon, N.H., through June 6.

Subject them to ‘Good Principles’

Noah Webster in 1833.

“To the Friends of Literature in the United States,” Webster's prospectus for his first dictionary of the English language, 1807-1808.

“The foundation of all free government and all social order must be laid in families and in the discipline of youth. Young persons must not only be furnished with knowledge, but they must be accustomed to subordination and subjected to the authority and influence of good principles. It will avail little that youths are made to understand truth and correct principles, unless they are accustomed to submit to be governed by them.”

—Noah Webster (1758-1843), of Connecticut, lexiographer (of dictionary fame), early textbook developer, political writer and author.

People over time

“Dinner Series: Lights Out, Chilmark, MA, July 5, 1998” (pigment print), by Stephen DiRado, in his show “Better Together: Four Decades of Photographs,’’ at the Fitchburg (Mass.) Art Museum, through June 1.

— Courtesy of the artist.

The museum says:

“Throughout his career, DiRado has worked in series, usually spanning many years and involving thousands of images, creating and representing communities of people in Worcester and Martha’s Vineyard. His photographic practice is intimately intertwined with his life – DiRado carries a camera everywhere and makes photographs every day. He operates within many of the great art historical traditions – portraiture, landscape, still life, and the nude. Through an aesthetic that combines realism and symbolism, he evokes deep human emotions like joy, melancholy, boredom, sensuality, vulnerability, compassion, and most of all, love. DiRado also creates images of the night sky, connecting celestial events with human culture.’’

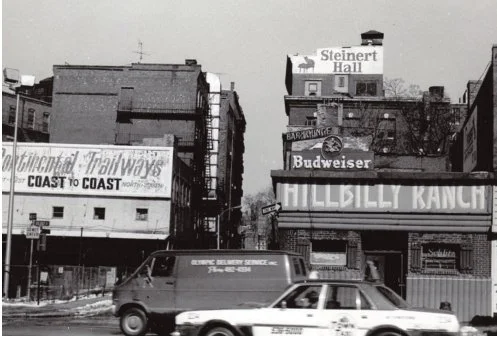

Remembering Hillbilly Ranch

— Photo courtesy of the Boston Landmarks Commission

Edited from a Boston Guardian article

(New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

Boston may be the hub of the universe, but it’s a thousand miles north of Nashville’s Grand Old Opry.

In the 1960s and 1970s, however, Park Square’s Hillbilly Ranch brought live country and western music to the city and helped Boston make its modest mark on the country- music landscape.

From 1960 to 1980, the Hillbilly Ranch was the only venue in Boston devoted to country music.

Something of a landmark with its stockade fence façade, the bar’s patrons could hear live country, western and bluegrass five nights a week. The bulk of the entertainers were locally based acts transplanted from across the south, but the bar also hosted performances by legends like Johnny Cash and Loretta Lynn.

The Hillbilly Ranch found success from the moment it opened its doors, tapping into two trends rapidly changing the face of the city. In the 1940s and 1950s, Americans from rural areas poured into cities where jobs were more plentiful. Boston was no exception, particularly in the wake of World War II and the Korean War. Boston, after all, was a major military center and (albeit declining) industrial center. These transplants had nowhere in Boston to hear the music they grew up on.

“In Boston, there were the shipyards in Charlestown and Quincy and factories all over town,” said photographer Henry Horenstein, a documentarian of country music history. “People came here for work, but at night they wanted a place to go out and hear their music.”

Soon after the Hillbilly Ranch opened its doors, Boston began demolishing Scollay Square, pushing the red-light district into the Combat Zone. Situated where the State Transportation Building now stands, the Hillbilly Ranch found an immediate clientele in the soldiers and sailors who frequented the area.

The bar was enough of a fixture on country’s national touring circuit that it was immortalized in a John Lincoln Wright song following its closure in 1980:

They tore down the Hillbilly Ranch The wrecking ball blew it away

They put up a government building The Hillbilly’s gone away.

Yet the Hillbilly’s influence on American music has not gone away. While New England has never been a fertile breeding ground for country musicians, the bar provided a home for the city’s small country scene throughout the 60s and 70s. These artists profoundly influenced Boston’s exploding folk revival scene in the 60s, and many of those musicians began mixing bluegrass and other rural American styles into their sound.

Two friends from Massachusetts founded Rounder Records in 1970 to give those artists a platform, launching the style that would eventually be known as “roots” or “Americana,” along with the careers of artists from George Thorogood and Bela Fleck to Alison Krauss.

“They discovered these folk singers that connected country and old time mountain music and bluegrass music,” said Horenstein. “They saved that music for posterity.”

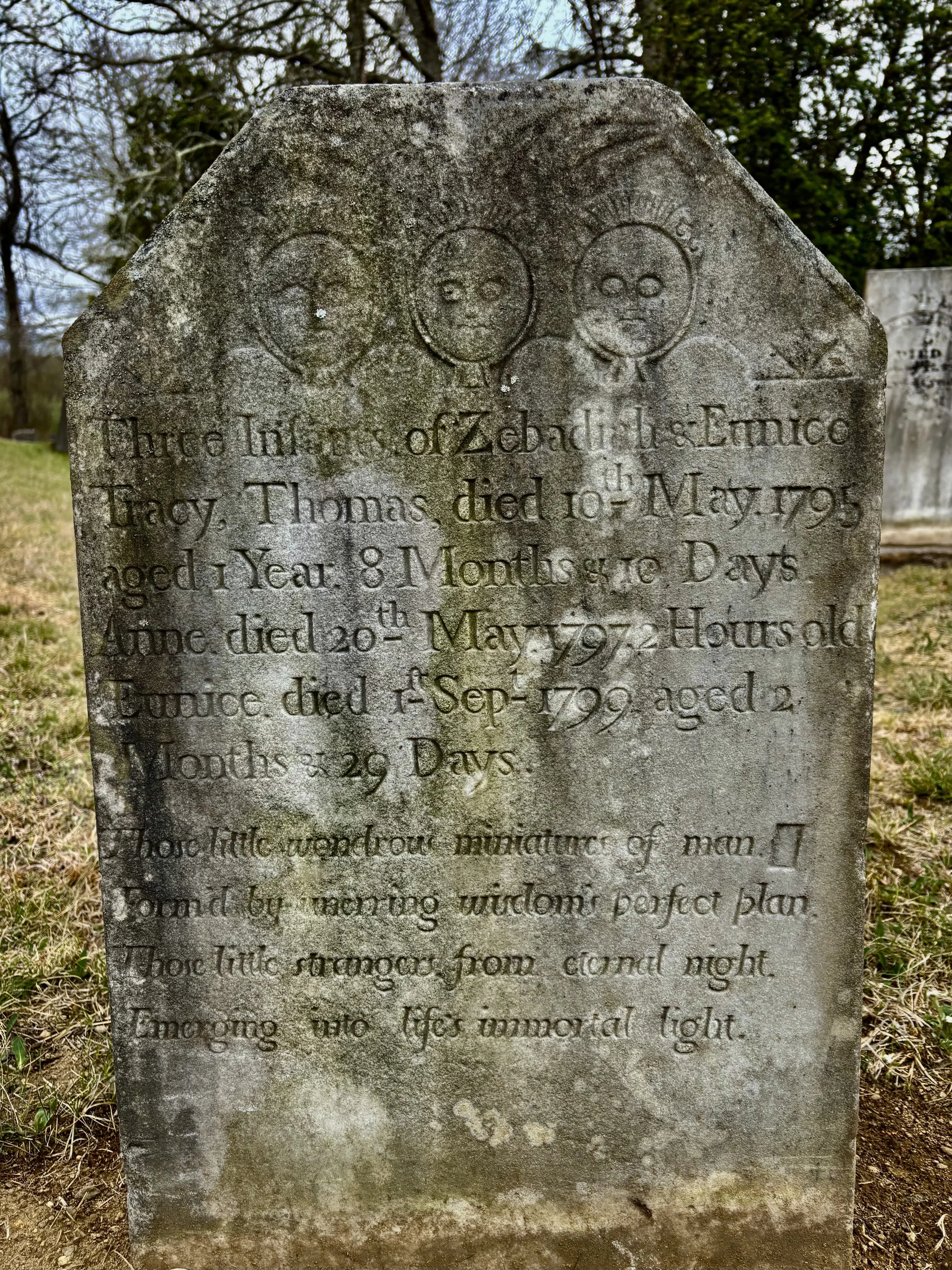

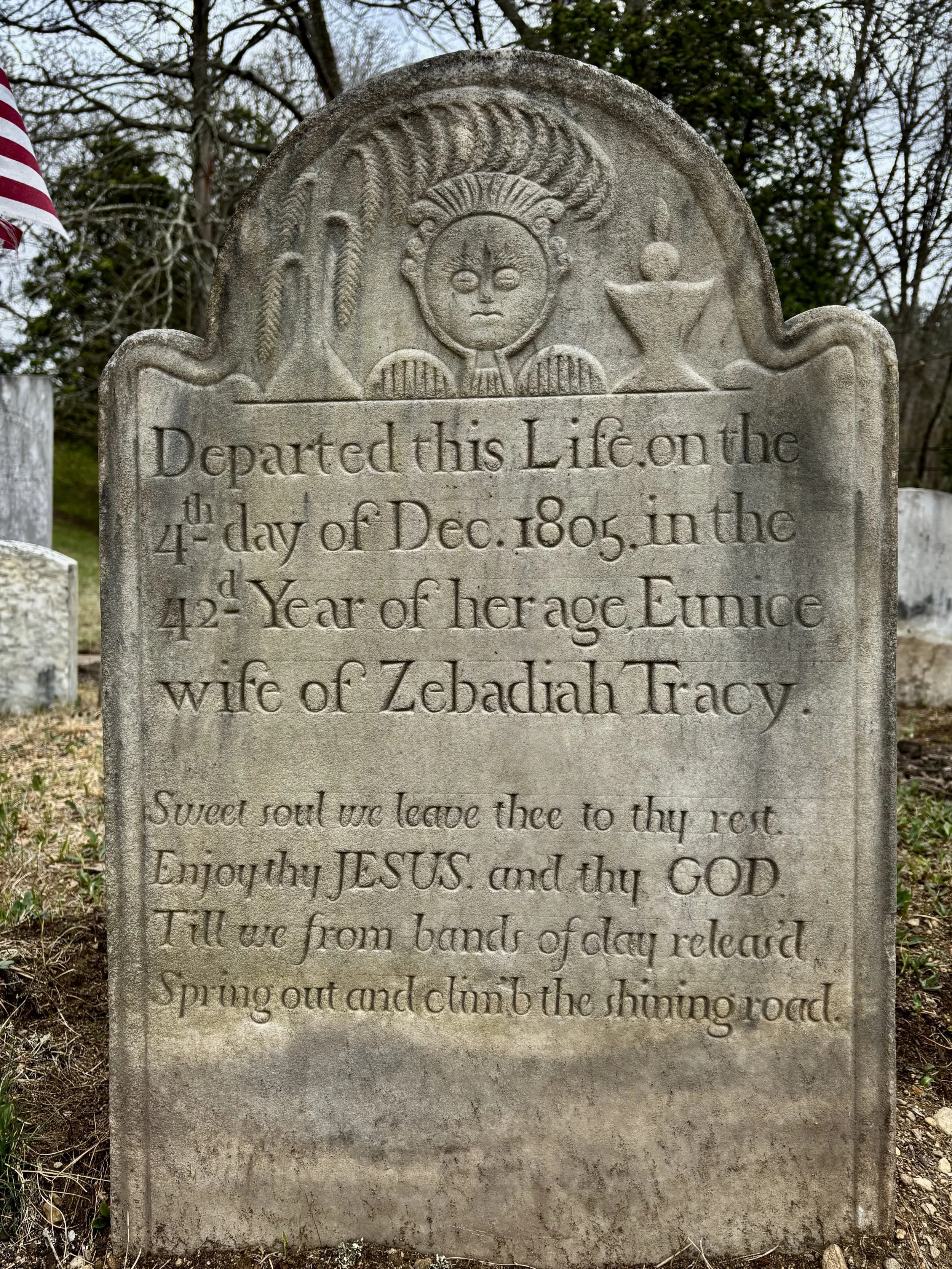

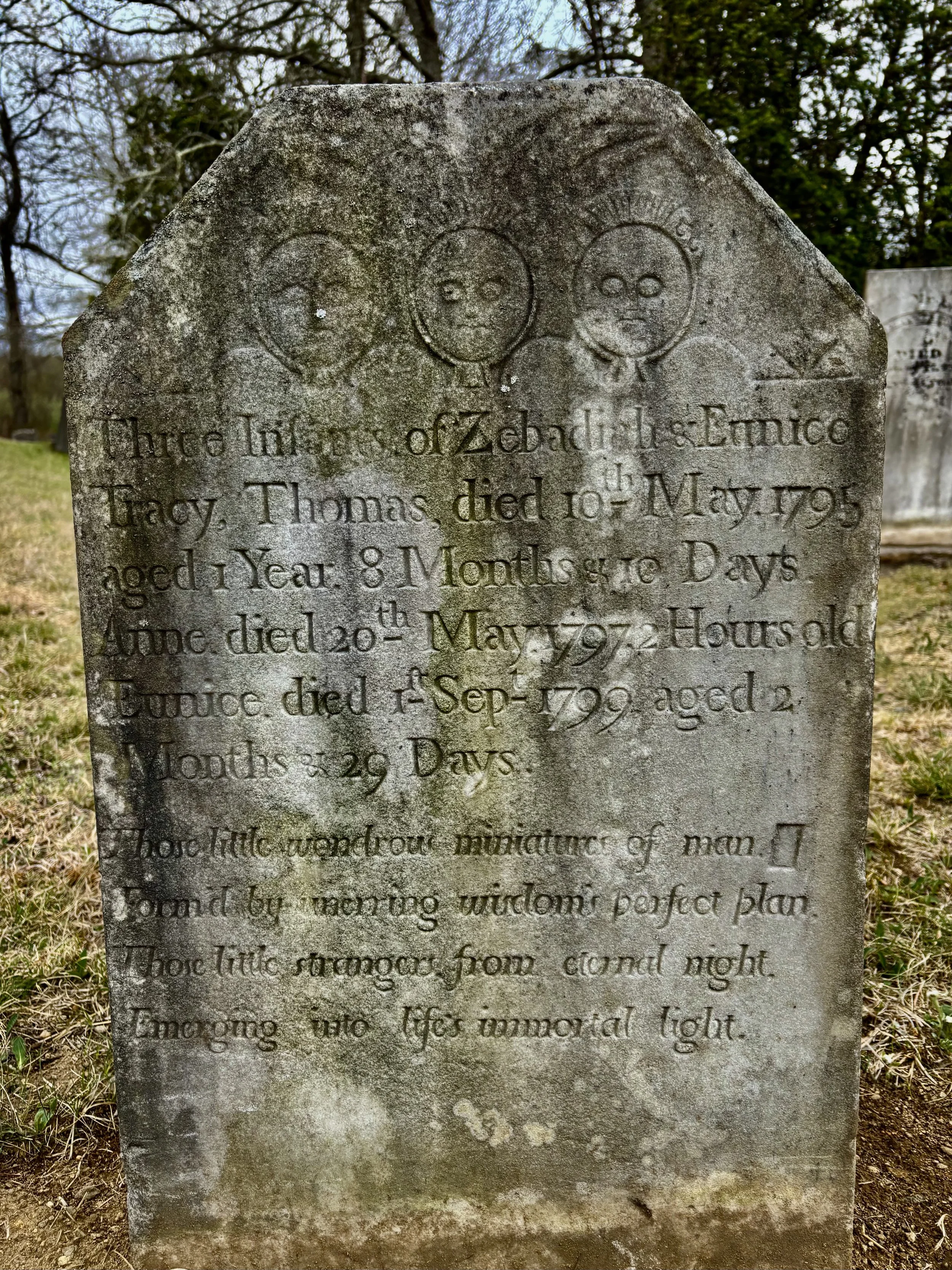

William Morgan: Haunting Stories from Cemetery in Bucolic Connecticut town

Scotland, a small town in northeastern Connecticut, was terra incognita until my wife, Carolyn, and I discovered it on a recent Sunday drive. Perhaps not the Edenic remembrance of first settler Isaac Magoon’s native Caledonia, but some time spent in the Windham County farming community revealed a modest treasure.

Set amongst some of the most bucolic topography of New England, with rolling hills, working farms, and an exceptional array of Cape Cod cottages, as well as Colonial and Greek Revival domestic architecture. The highlight of this gentle landscape was the steep hillside burial ground that contains two centuries of the town’s dead.

Old Scotland Cemetery North on Devotion Road. (There is a newer cemetery half a mile south.)

One stone from the late 18th Century is identified as a cenotaph, that is, a marker for someone who’s body is buried elsewhere, in the this case, the Caribbean Island of St. Lucia. Scotland may have been isolated, but it was not provincial. There are three standard Civil War graves stones, but surely these, too, lack the physical remains of the young men they memorialize.

During the first half of 1862, Union General (and Rhode Islander) Ambrose Burnside, employing New England regiments, tried to shut down Confederate blockade-running operations along the Outer Banks. Amos Weaver was presumably wounded in the Battle for Roanoke Island, dying of his wounds five days later.

The government-issue marble stones are the exception in Old Scotland. Most of the dead here lie beneath sandstone, a rarity when one recalls the typical slate steles of 18th-Century New England. Scotland had more than one artisanal stone carver. Joseph Manning and his sons Rockwell and Frederick contributed tombstones to the area for over six decades. It was John Walden, however, who provided Scotland with unique round faces.

Thomas, aged 1 year and 8 months, Anne lived but 2 hours, and Eunice expired at less than 3 months, 1795-99.

“Those little wondrous miniatures of man.

Form’d by unerring wisdom of perfect plan.

Those little strangers from eternal night.

Emerging from life’s immortal light.”

Mother of Thomas, Anna, and Eunice, 1805. Walden’s signature circular visage is almost subsumed by a weeping tree, and illuminated by a ghost-like lamp. Note the stylized wings of the departed.

“Mrs Bethiah, Consort to Capt Saml Morgan. Departed this Life Feb. 2d 1800, in the 61st Year of her age.

Left numerous offspring to Lament their loss.” Walden’s angel wings roll around the semicircle as decorative curtains.

Lydia Ripley was 79 when she departed this life in 1784. Primitive, unsophisticated, but powerful.

Providence-based writer and photographer William Morgan has written extensively about New England architecture and other art, townscape and landscape. His latest book is The Cape Cod Cottage (Abbeville Press).

Old Scotland Cemetery North

Scotland, a small town in northeastern Connecticut was terra incognita until Carolyn and

I discovered it on a recent Sunday drive. Perhaps not the Edenic remembrance of first settler

Isaac Magoon’s native Caledonia, but some time spent in the Windham County farming

community revealed a modest treasure. Set amongst some of the most bucolic topography of

New England, with rolling hills, working farms, and an exceptional array of Cape Cod cottages,

as well as Colonial and Greek Revival domestic architecture. The highlight of this gentle

landscape was the steep hillside burial ground that contains two centuries of the town’s dead.

Old Scotland Cemetery North on Devotion Road. (There is a newer cemetery half a mile south.)

One stone from the late 18 th century is identified as a cenotaph, that is, a marker for

someone who’s body is buried elsewhere, in the this case, the Caribbean Island of St. Lucia.

Scotland may have been isolated, but it was not provincial. There are three standard Civil War

graves stones, but surely these, too, lack the physical remains of the young men they

memorialize.

During the first half of 1862, Union General (and Rhode Islander) Ambrose Burnside, employing New England regiments,

attempted to shut down blockade-running operations along the Outer Banks. Amos Weaver was

presumably wounded in the Battle for Roanoke Island, dying of his wounds five days later.England regiments,

attempted to shut down blockade-running operations along the Outer Banks. Amos Weaver was

presumably wounded in the Battle for Roanoke Island, dying of his wounds five days later.

The government-issue marble stones are the exception in Old Scotland. Most of the dead

here lie beneath sandstone, a rarity when one recalls the typical slate steles of 18 th -century New

England. Scotland had more than one artisanal stone carver. Joseph Manning and his sons

Rockwell and Frederick contributed tombstones to the area for over six decades. It was John

Walden, however, who provided Scotland with unique round faces.

Thomas, aged 1 year and 8 months, Anne lived but 2 hours, and Eunice expired at less than 3 months,

1795-99.

Those little wondrous miniatures of man.

Form’d by unerring wisdom of perfect plan.

Those little strangers from eternal night.

Emerging from life’s immortal light.

Mother of Thomas, Anna, and Eunice, 1805. Walden’s signature circular visage is almost subsumed by a

weeping tree,

illuminated by a ghost-liked lamp. Note the stylized wings of the departed.

“Mrs Bethiah, Consort to Capt Saml Morgan. Departed this Life Feb. 2d 1800, in the 61 st Year of

her age.

Left numerous offspring to Lament their loss.” Walden’s angel wings roll around the semicircle as

decorative curtains.

Lydia Ripley was 79 when she departed this life in 1784. Primitive, unsophisticated, but

powerful.

Providence-based writer and photographer, William Morgan, has written extensively about New

England architecture and art, townscape and landscape. His latest book is The Cape Cod Cottage

‘Quiet disruption’

“Peace Offering III’’ (mixed fabricated and foraged materials on canvas), by Luanne E. Witkowski, in her show “Quiet Disruption,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, June 1-30.

She says:

“This is my peace offering, a quiet distraction, amidst the constant noise and chaos…

“There is so much beauty in this world that these works invite us all to live and fight for. My work combines my love for nature’s endless transitions and transformations, of changing color, temperature, drama with the practice of being in the studio with my assorted materials and wild foraged collections.’’

“It is a message of quiet disruption; a respite amidst the whirling storm raging all around that remembers ‘I am here.”’

Michael Anteby: In praise of Bureaucracy

Michel Anteby is a professor of management and organizations and sociology at Questrom School of Business & College of Arts and Sciences at Boston University.

Michel Anteby was during a decade a member of the Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth and a former Vice-Chair, and then Chair of the Commission.

From The Conversation (except for image above)

BOSTON

It’s telling that U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration wants to fire bureaucrats. In its view, bureaucrats stand for everything that’s wrong with the United States: overregulation, inefficiency and even the nation’s deficit, since they draw salaries from taxpayers.

But bureaucrats have historically stood for something else entirely. As the sociologist Max Weber argued in his 1921 classic “Economy and Society,” bureaucrats represent a set of critical ideals: upholding expert knowledge, promoting equal treatment and serving others. While they may not live up to those ideals everywhere and every day, the description does ring largely true in democratic societies.

I know this firsthand, because as a sociologist of work I’ve studied federal, state and local bureaucrats for more than two decades. I’ve watched them oversee the handling of human remains, screen travelers for security threats as well as promote primary and secondary education. And over and over again, I’ve seen bureaucrats stand for Weber’s ideals while conducting their often-hidden work.

Bureaucrats as experts and equalizers

Weber defined bureaucrats as people who work within systems governed by rules and procedures aimed at rational action. He emphasized bureaucrats’ reliance on expert training, noting: “The choice is only that between ‘bureaucratisation’ and ‘dilettantism.’” The choice between a bureaucrat and a dilettante to run an army − in his days, like in ours − seems like an obvious one. Weber saw that bureaucrats’ strength lies in their mastery of specialized knowledge.

I couldn’t agree more. When I studied the procurement of whole body donations for medical research, for example, the state bureaucrats I spoke with were among the most knowledgeable professionals I encountered. Whether directors of anatomical services or chief medical examiners, they knew precisely how to properly secure, handle and transfer human cadavers so physicians could get trained. I felt greatly reassured that they were overseeing the donated bodies of loved ones.

The sociologist Max Weber, pictured here circa 1917, wrote extensively about bureaucracy. Archiv Gerstenberg/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Weber also described bureaucrats as people who don’t make decisions based on favors. In other forms of rule, he noted, “the ruler is free to grant or withhold clemency” based on “personal preference,” but in bureaucracies, decisions are reached impersonally. By “impersonal,” Weber meant “without hatred or passion” and without “love and enthusiasm.” Put otherwise, the bureaucrats fulfill their work without regard to the person: “Everyone is treated with formal equality.”

The federal Transportation Security Administration officers who perform their duties to ensure that we all travel safely epitomize this ideal. While interviewing and observing them, I felt grateful to see them not speculate about loving or hating anyone but treating all travelers as potential threats. The standard operating procedures they followed often proved tedious, but they were applied across the board. Doing any favors here would create immense security risks, as the recent Netflix action film “Carry-On” − about an officer blackmailed into allowing a terrorist to board a plane − illustrates.

Advancing the public’s interests

Finally, Weber highlighted bureaucrats’ commitment to serving the public. He stressed their tendency to act “in the interests of the welfare of those subjects over whom they rule.” Bureaucrats’ expertise and adherence to impersonal rules are meant to advance the common interest: for young and old, rural and urban dwellers alike, and many more.

The state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education staff that I partnered with for years at the Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth exemplified this ethic. They always impressed me by the huge sense of responsibility they felt toward all state residents. Even when local resources varied, they worked to ensure that all young people in the state − regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity − could thrive. Based on my personal experience, while they didn’t always get everything right, they were consistently committed to serving others.

Today, bureaucrats are often framed by the administration and its supporters as the root of all problems. Yet if Weber’s insights and my observations are any guide, bureaucrats are also the safeguards that stand between the public and dilettantism, favoritism and selfishness. The overwhelming majority of bureaucrats whom I have studied and worked with deeply care about upholding expertise, treating everyone equally and ensuring the welfare of all.

Yes, bureaucrats can slow things down and seem inefficient or costly at times. Sure, they can also be co-opted by totalitarian regimes and end up complicit in unimaginable tragedies. But with the right accountability mechanisms, democratic control and sufficient resources for them to perform their tasks, bureaucrats typically uphold critical ideals.

In an era of growing hostility, it’s key to remember what bureaucrats have long stood for − and, let’s hope, still do.

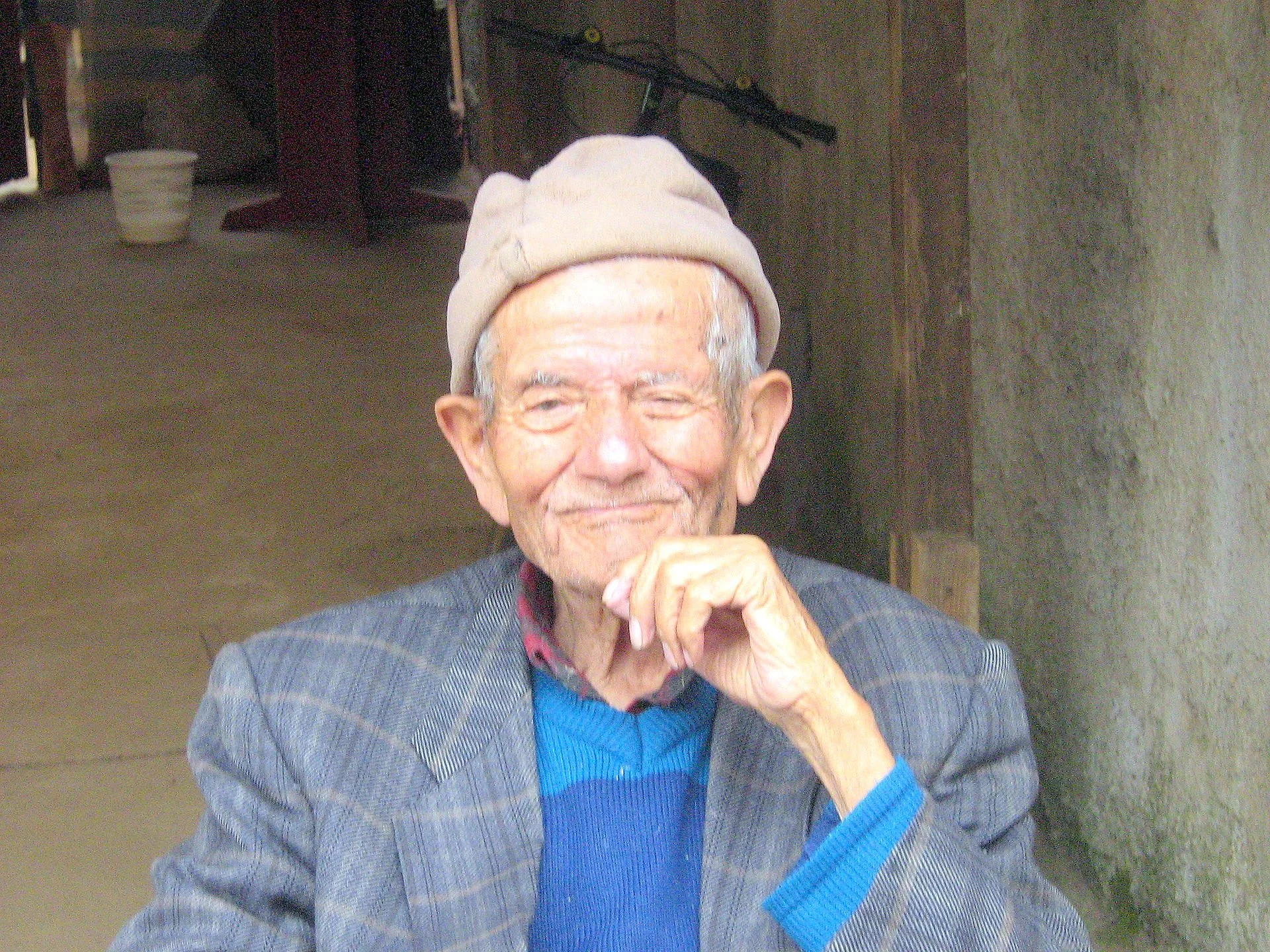

Paula Span: When they don’t recognize you Anymore

—Photo by Diego Grez Cañete

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (except for image above)

It happened more than a decade ago, but the moment remains with her.

Sara Stewart was talking at the dining room table with her mother, Barbara Cole, 86 at the time, in Bar Harbor, Maine. Stewart, then 59, a lawyer, was making one of her extended visits from out of state.

Two or three years earlier, Cole had begun showing troubling signs of dementia, probably from a series of small strokes. “I didn’t want to yank her out of her home,” Stewart said.

So with a squadron of helpers — a housekeeper, regular family visitors, a watchful neighbor, and a meal delivery service — Cole remained in the house she and her late husband had built 30-odd years earlier.

She was managing, and she usually seemed cheerful and chatty. But this conversation in 2014 took a different turn.

“She said to me: ‘Now, where is it we know each other from? Was it from school?’” her daughter and firstborn recalled. “I felt like I’d been kicked.”

Stewart remembers thinking, “In the natural course of things, you were supposed to die before me. But you were never supposed to forget who I am.” Later, alone, she wept.

People with advancing dementia do regularly fail to recognize beloved spouses, partners, children, and siblings. By the time Stewart and her youngest brother moved Cole into a memory-care facility a year later, she had almost completely lost the ability to remember their names or their relationship to her.

“It’s pretty universal at the later stages” of the disease, said Alison Lynn, director of social work at the Penn Memory Center, who has led support groups for dementia caregivers for a decade.

She has heard many variations of this account, a moment described with grief, anger, frustration, relief, or some combination thereof.

These caregivers “see a lot of losses, reverse milestones, and this is one of those benchmarks, a fundamental shift” in a close relationship, she said. “It can throw people into an existential crisis.”

It’s hard to determine what people with dementia — a category that includes Alzheimer’s disease and many other cognitive disorders — know or feel. “We don’t have a way of asking the person or looking at an MRI,” Lynn noted. “It’s all deductive.”

But researchers are starting to investigate how family members respond when a loved one no longer appears to know them. A qualitative study recently published in the journal Dementia analyzed in-depth interviews with adult children caring for mothers with dementia who, at least once, did not recognize them.

“It’s very destabilizing,” said Kristie Wood, a clinical research psychologist at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and co-author of the study. “Recognition affirms identity, and when it’s gone, people feel like they’ve lost part of themselves.”

Although they understood that nonrecognition was not rejection but a symptom of their mothers’ disease, she added, some adult children nevertheless blamed themselves.

“They questioned their role. ‘Was I not important enough to remember?’” Wood said. They might withdraw or visit less often.

Pauline Boss, the family therapist who developed the theory of “ambiguous loss” decades ago, points out that it can involve physical absence — as when a soldier is missing in action — or psychological absence, including nonrecognition because of dementia.

Society has no way to acknowledge the transition when “a person is physically present but psychologically absent,” Boss said. There is “no death certificate, no ritual where friends and neighbors come sit with you and comfort you.”

“People feel guilty if they grieve for someone who’s still alive,” she continued. “But while it’s not the same as a verified death, it is a real loss and it just keeps coming.”

Nonrecognition takes different forms. Some relatives report that while a loved one with dementia can no longer retrieve a name or an exact relationship, they still seem happy to see them.

“She stopped knowing who I was in the narrative sense, that I was her daughter Janet,” Janet Keller, 69, an actress in Port Townsend, Washington, said in an email about her late mother, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. “But she always knew that I was someone she liked and wanted to laugh with and hold hands with.”

It comforts caregivers to still feel a sense of connection. But one of the respondents in the dementia study reported that her mother felt like a stranger and that the relationship no longer provided any emotional reward.

“I might as well be visiting the mailman,” she told the interviewer.

Larry Levine, 67, a retired health-care administrator in Rockville, Maryland, watched his husband’s ability to recognize him shift unpredictably.

He and Arthur Windreich, a couple for 43 years, had married when Washington, D.C., legalized same-sex marriage in 2010. The following year, Windreich received a diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Levine became his caregiver until his death, at 70, in late 2023.

“His condition sort of zigzagged,” Levine said. Windreich had moved into a memory-care unit. “One day, he’d call me ‘the nice man who comes to visit’,” Levine said. “The next day he’d call me by name.”

Even in his final years when, like many dementia patients, Windreich became largely nonverbal, “there was some acknowledgment,” his husband said. “Sometimes you could see it in his eyes, this sparkle instead of the blank expression he usually wore.”

At other times, however, “there was no affect at all.” Levine often left the facility in tears.

He sought help from his therapist and his sisters, and recently joined a support group for LGBTQ+ dementia caregivers even though his husband has died. Support groups, in person or online, “are medicine for the caregiver,” Boss said. “It’s important not to stay isolated.”

Lynn encourages participants in her groups to also find personal rituals to mark the loss of recognition and other reverse milestones. “Maybe they light a candle. Maybe they say a prayer,” she said.

Someone who would sit shiva, part of the Jewish mourning ritual, might gather a small group of friends or family to reminisce and share stories, even though the loved one with dementia hasn’t died.

“To have someone else participate can be very validating,” Lynn said. “It says, ‘I see the pain you’re going through.’”

Once in a while, the fog of dementia seems to lift briefly.

Researchers at Penn and elsewhere have pointed to a startling phenomenon called “paradoxical lucidity.”

Someone with severe dementia, after being noncommunicative for months or years, suddenly regains alertness and may come up with a name, say a few appropriate words, crack a joke, make eye contact, or sing along with a radio.

Though common, these episodes generally last only seconds and don’t mark a real change in the person’s decline. Efforts to recreate the experiences tend to fail.

“It’s a blip,” Lynn said. But caregivers often respond with shock and joy; some interpret the episode as evidence that despite deepening dementia, they are not truly forgotten.

Stewart encountered such a blip a few months before her mother died. She was in her mother’s apartment when a nurse asked her to come down the hall.

“As I left the room, my mother called out my name,” she said. Though Cole usually seemed pleased to see her, “she hadn’t used my name for as long as I could remember.”

It didn’t happen again, but that didn’t matter. “It was wonderful,” Stewart said.

Paula Span is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter.