Joanne M. Pierce:What will happen at Pope Francis’s funeral

Pope Francis

Joanne M. Pierce is a professor emerita of religious studies at The College of the Holy Cross, in Worcester.

Joanne M. Pierce does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic appointment.

Except for image above, this is from The Conversation

The 88-year-old pontiff had been well aware of his fragile state and advanced age. As early as 2015, Pope Francis had expressed the desire to be buried in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, a fifth-century church in Rome dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary. He was so devoted to Mary and her basilica that after each of his more than 100 trips abroad, he would visit it after returning to Rome to pray and meditate.

No pope has been buried in Santa Maria Maggiore since the 17th Century, when Pope Clement IX was laid to rest there.

I’m a specialist in Catholic liturgical history. In earlier centuries, papal funerals have been elaborate affairs, ceremonies befitting a Renaissance prince or other regal figure. But in recent years, the rites have been simplified. As Pope Francis has mandated, here are the steps that the ritual will follow.

First station: Preparation of the body

The funeral rites take place in three parts, called stations. The first takes place in the pope’s private chapel, after medical professionals have certified his death. Until recently, this stage had taken place at the pope’s bedside.

After the body lies in rest in the chapel, the cardinal serving as the pope’s camerlengo – the pope’s chief of staff – will make the arrangements for the funeral. He is also tasked with running the Vatican until a new pope is elected. The current camerlengo is Cardinal Kevin Joseph Farrell, appointed by Francis in 2019.

As has been done for centuries, the camerlengo will formally call the deceased pope by the full name given to him when he was baptized as an infant – Jorge Mario Bergoglio. There are narratives or legends stating that, at this time, the pope was also tapped three times on the forehead with a small silver hammer. However, there is no documented proof that this was actually done in earlier centuries to verify a pope’s death.

Traditionally, another ancient rite will also take place after the declaration of the pope’s death: the defacing of the pope’s ring. Each pope wears a custom-made ring with an engraved image of a man fishing from a boat, hearkening back to the gospel of Matthew, where Jesus calls St. Peter a “fisher of men.” This Fisherman’s Ring, with the name of the current pope engraved over the image, could act as a seal on official documents. The camerlengo will break Francis’ ring and smash the seal with a hammer or other instrument to prevent any other person from using it.

The pope’s apartments will also be locked, with no one allowed to enter; traditionally, this was done to prevent looting.

Second station: Viewing the body

The deceased pope will be dressed in his simple white cassock and red vestments, then placed in a simple wooden coffin. This will be carried in procession to St. Peter’s Basilica, where the public viewing will take place for the next three days.

The pope’s body will be left in the plain, open casket during this viewing period in order to emphasize the pope’s humble role as a pastor, not a head of state. The earlier practice would have been to place the body on top of a tall raised platform, called a catafalque; this ended with the funeral of Pope Benedict XVI in 2022.

Pope Benedict was also the last pope to be buried in the traditional three coffins of cypress, lead and elm. Two coffins contained specific documents about his pontificate; the first coffin also held the traditional three bags of coins – gold, silver and copper – representing each year of his pontificate.

At Francis’s funeral, after the public viewing, a plain white cloth will be placed over the pope’s face as he lies in the oak coffin, a continuing part of papal funerals. But this will be the first time that only a single coffin will be used; it will likely contain a document describing his pontificate and a bag of coins from his pontificate as well.

The funeral Mass will then be celebrated at St. Peter’s, and there will likely be a crowd of believers outside, assembled on the plaza. The homily will reflect on the life and spirituality of the deceased pope; Francis himself preached at the funeral of his retired predecessor, Pope Benedict. And the future Pope Benedict, as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, preached at the funeral of Pope St. John Paul II when Ratzinger was the leader, or the dean, of all senior church officials – what’s known as the College of Cardinals.

The current dean is 91-year-old Cardinal Giovanni Battista Re, and it is unclear whether he will be able to continue this tradition due to his advanced age. Masses will continue to be said in Francis’ memory for nine days after his death – a period called the Novendialis. This ritual was inspired by an ancient Roman tradition prescribing a mourning period ending on the ninth day after a death.

Third station: Burial

Why does Pope Francis want to be buried in St. Mary Major and not in the Vatican?

Popes in the past have been buried in several different places. Until the legalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire in the early fourth century, popes would be interred in the catacombs, the burial grounds on the outskirts of Rome.

Afterward, popes could be buried in a number of different locations, such as the Basilica of St. John Lateran – the official cathedral of Rome – or other churches in and around Rome. A few were even buried in France during the 14th century, when the papacy moved to the French border for political reasons.

Most popes are buried in the grottoes underneath St. Peter’s, and since Pope Leo XIII’s burial at St. John Lateran in 1903, every pope has been buried at St. Peter’s. According to Francis’ wishes, however, there will likely be a procession across Rome to Santa Maria Maggiore, including the hearse and cars carrying others who will attend this private ritual.

After a few final prayers and sprinkling of holy water, the coffin will be placed in its final location inside the church. Only later will the area be opened to the public for prayers and veneration.

After so many journeys from Rome to visit Catholic communities in countries across the globe, and so many visits to this basilica for prayer and meditation, it seems fitting that, at the end of his life’s journey, Francis would make one last trip to the church he loved so much to be laid to rest forever.

Holding Hands in the fake forest

Norway spruce

“In the false New England forest

where the misplanted Norwegian trees

refused to root, their thick synthetic

roots barging out of the dirt to work on the air,

we held hands and walked on our knees.''--From “The Expatriates,'' by Anne Sexton (1928

-1974), Massachusetts poet

The honor of being Booed

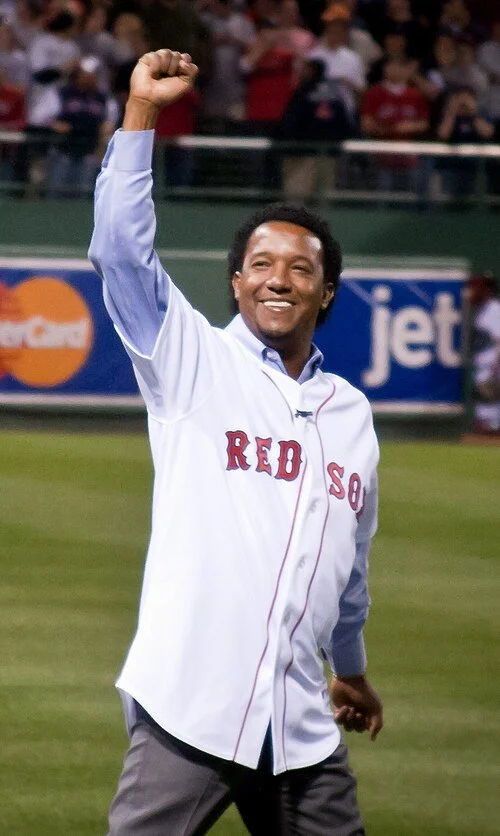

Pedro Martinez in 2010.

“It actually made me feel really, really good. I actually realized that I was somebody important, because I caught the attention of 60,000 people, plus you guys [reporters], plus the whole world watching a guy that if you reverse time back 15 years ago, I was sitting under a mango tree without 50 cents to actually pay for a bus. And today I was the center of the attention of the whole city of New York.’’

— Former Red Sox pitcher Pedro Martinez (born 1971) on being booed by Yankees fans at Yankee Stadium on Oct. 13, 2004 in Game 2 of the American League Championship series.

Down to essentials

“Sun, Manana, Mohegan” (1907 oil on canvas), by Rockwell Kent (1882-1971), in the show “Art, Ecology, and the Resilience of a Maine Island,’’ at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, through June 1.

Global Warming Throws off New England species

A Saltmarsh Sparrow. The species is predicted to go extinct in the next 15 to 20 years as rising sea levels flood marshes along the East Coast.

Text excerpted from an ecoRI News article

“This is part of an ecoRI News series called Wild New England . The region’s collection of native species is under threat on several fronts, most notably from humanity’s shortsightedness. Humans aren’t giving the natural world the space it needs and deserves. We’re crowding out non-human life, which, in turn, makes nature less productive and us less healthy. Wild New England examines the animals and insects most at risk.’’

“The work of Charles Clarkson, the Audubon Society of Rhode Island’s director of avian research, has documented the challenges birds face as the climate crisis increases the unpredictability of weather. Species that have timed their migratory movements over thousands of generations to coincide with gradual spring warming or autumn cooling are finding themselves out of whack with the plant and insect communities they rely on.

“This climate mismatch is leading to avian population declines, particularly with those species that undergo long-distance migration, such as the common yellowthroat, the wood thrush, and the American goldfinch.’’

U.S. is Perilously behind in rare earths Arena

A fine-grained volcanic rock (trachyte) that hosts rare earth elements niobium and zirconium, considered critical mineral resources. This rock was found on Pennington Mountain in Maine.

— Image courtesy of Chunzeng Wang, University of Maine-Presque Isle

Geologists have identified Pennington Mountain as potentially a very important source of rare earth minerals, which are essential for key U.S. industrial sectors. Read Llewellyn King’s column on how America has failed by a long shot to adequately develop rare earth mining and processing.

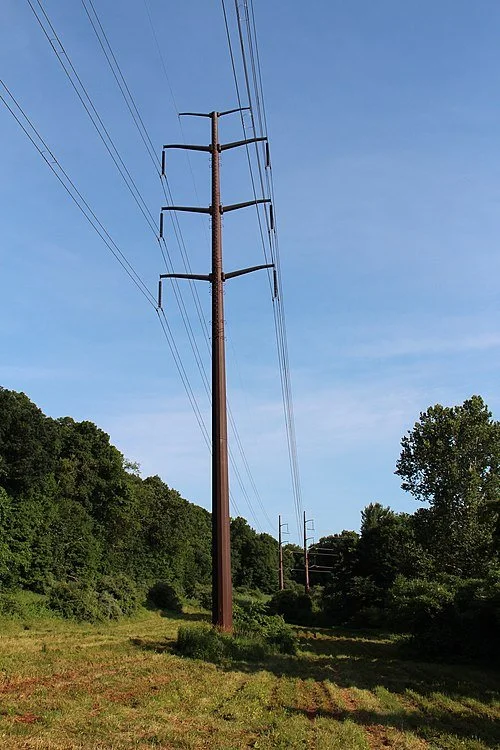

Chris Powell: Welfare hides in Conn. Electricity Bills; toilets on the Green

Electricity transmission line in Brookfield, Conn.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Why should Connecticut's electricity grid be incorporated into the state's welfare system? Why are electricity users in the state who pay their own electric bills being charged extra to subsidize discounts for electricity used by poor people who don't pay? Why aren't those subsidies financed by general taxation?

Those questions were prompted by a recent report from Connecticut Inside Investigator's Marc E. Fitch, who discovered that the Low-Income Discount Rate Program of the state Public Utilities Regulatory Authority is giving $137 million in electricity discounts ranging from 10 to 50% to low-income electricity users. They are automatically enrolled for the discounts through the authority's data-sharing arrangement with the state Social Services Department.

Everyone classified by the welfare department as being poor in one respect or another is identified to the state's major electricity distributors, Eversource and United Illuminating, and then the companies are required to reduce bills accordingly.

The discounts are recovered through higher rates to everyone else.

This exploitation of electricity customers has been going on in Connecticut in various forms for a long time. The Low-Income Discount Rate Program, begun last year, is just the most extreme form, since, predictably enough, it has turned out to cost many millions more than estimated. The program is one reason why the “public benefits" surcharges on electric bills are so high.

Republican state legislators argue that welfare expenses should be transferred out of electricity bills and into the state budget. Democratic legislators, who hold a large majority in the General Assembly, oppose such transparency but have never clearly explained why.

That's why the questions reiterated above remain compelling even though their answers can be inferred. Democratic legislators like hiding taxes in electricity bills, for then the public blames the electric companies for high electricity prices instead of the mistaken and deceptive government policies that actually have driven them up.

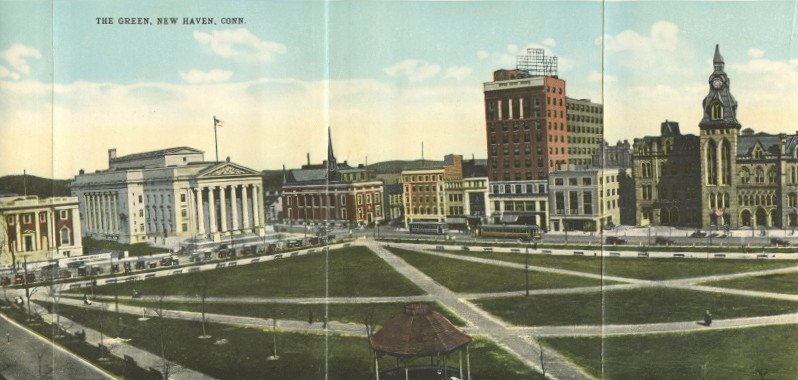

TOILETS ON THE GREEN: Homeless people and their political advocates gathered at a school in New Haven the other day to berate Mayor Justin Elicker for not yet having turned the city's downtown green into a homeless encampment complete with plenty of sparkling-clean portable toilets.

The mayor was at the school to discuss his city budget proposal but dutifully explained that the portable toilets already installed on the green are hard to maintain because people sometimes use them for prostitution, drug injections, and disposal of hypodermic needles and other trash. Elicker noted that toilets in city libraries are free for the homeless to use. But maybe those toilets are not as suitable for everyone because libraries expect decent conduct.

Nevertheless, the homeless people and their advocates urged the mayor to add $500,000 to his budget for more portable toilets on the green.

Homelessness is a worsening problem in Connecticut. Part of it is the state's shortage of housing, the result of long-negligent state government policy, and part of it is the mental illness of the homeless themselves.

But Mayor Elicker isn't responsible for the problem. To the contrary, his administration is greatly facilitating housing construction in the city. Meanwhile Governor Lamont's administration plans a substantial increase in “supportive housing" for people recovering from addiction.

One of the homeless advocates berating the mayor the other day asked why the city doesn't get more money to spend by taxing Yale University, which owns much tax-exempt property in New Haven. The mayor said he'd like to tax Yale but the city doesn't have that authority. He might have added that state government, controlled by members of his party, has the power to tax Yale but for now has left the university as one of the few things in Connecticut that isn't taxed, and that the homeless might go to the state Capitol and ask about that.

Better still, the mayor also might have asked the homeless what they plan to do to help themselves and the city. They didn't volunteer to keep the portable toilets clean and as usual seemed to think that the world, or at least the city, owes them a living.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

A few years ago: Part of the New Haven Green, without homeless people or portable toilets.

Part of a panoramic view of The New Haven Green in a “souvenir folder" mailed in 1919. The New Haven County Courthouse is the building with six pillars, left of center.

William Morgan: Will this give MAGA design ideas?

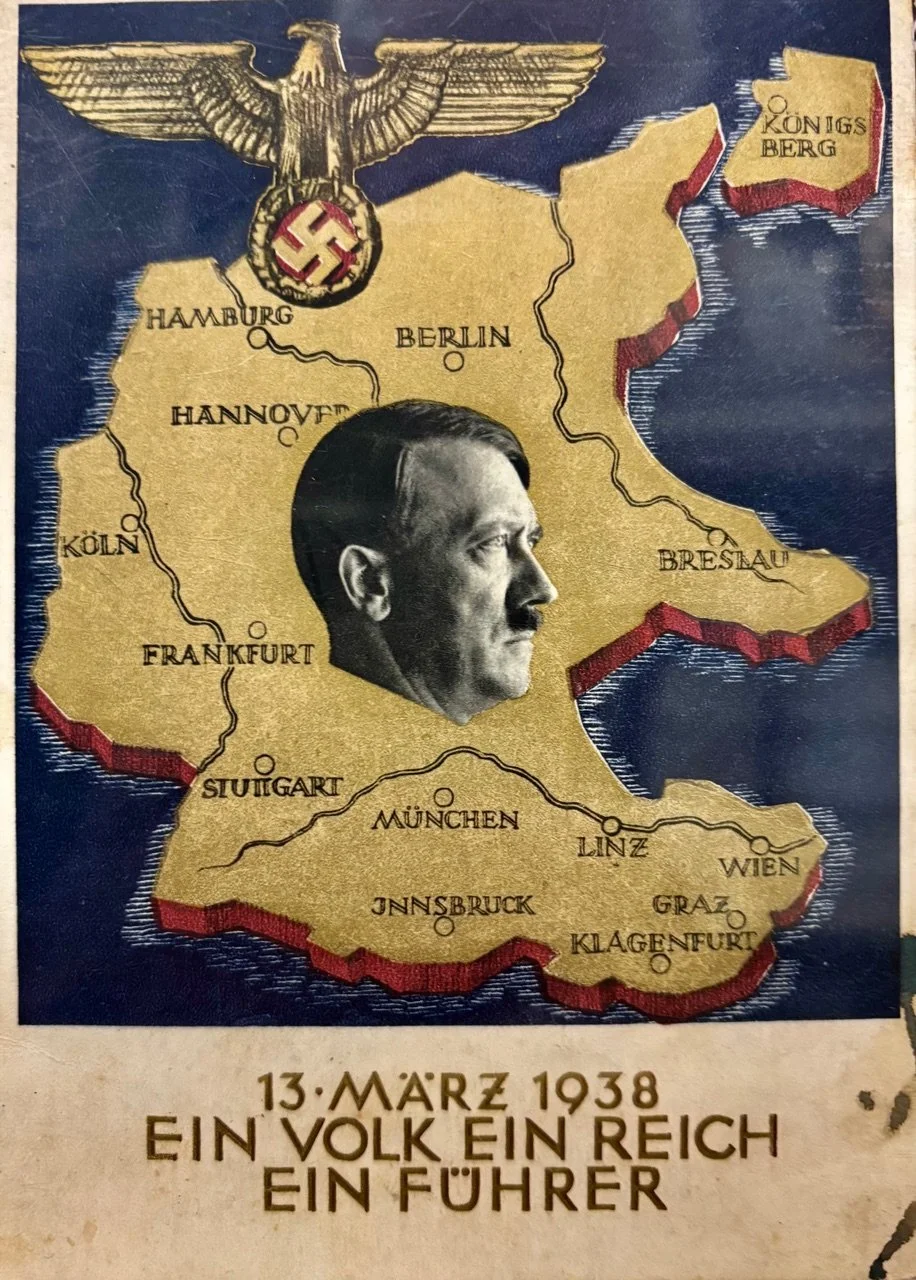

I am forever searching boxes of postcards in antique stores and junk shops, looking for scenes of New England houses, villages, or landscapes. Imagine my surprise, when amidst a bunch of old Easter Bunny cards, Adolf Hitler appeared.

Like an horrific version of a commemorative first-day cover, this was postmarked less than a month after the Anschluss — the forced unification of Germany and Austria into “One People, One State, One Leader’’.

There must have been thousands of these cards ready to mail. The cards had stamps of both countries, but the German one packs punchier nationalistic realism, with two handsome Aryan youths waving the swastika flag.

There have recently been a lot of memes, satirical skits, and genuine concern about parallels between the current American presidency and 1930s Germany. For example, will the word Anschluss be resurrected if the United States invades Canada? After all, we are two former British colonies sharing (mostly) the same language and somewhat similar cultures, as do Germany and Austria.

Politics aside, Hitler’s propaganda machine had better designers than our current maximum leader has, and this relentless artificially tanned tyrannical toddler, with his Palm Beach Baroque gilded backdrops, will never be half as handsome as the 20th-Century’s maddest madman.

In any case, our wannabe strongman, like the unsuccessful Viennese art student, may well implode in a fiery Götterdämmerung.

Everything about Hitler is grotesque, yet his Wagnerian propaganda had a certain style that precluded clownish long red neckties

William Morgan is an architecture writer based in Providence, and author of numerous books, the latest of which is The Cape Cod Cottage (Abbeville Press). He’s a descendant of one of the Lexington Minutemen. The Battles of Lexington and Concord took place on April 19, 1775, launching the American Revolution.

Easter formal

A heavily hatted Easter in Boston in 1940.

From Anthony Sammarco’s book Easter Traditions in Boston

“Having attended Easter Services at Trinity Church in the Back Bay, these people walked along Clarendon Street headed toward the Commonwealth Avenue Mall for the Easter Parade in 1940.

“Women wore hats and corsages, white gloves, and their coats had mink, ocelot, chinchilla, and fox furs. In the distance is the entrance to the Brunswick Casino in the Hotel Brunswick. The Casino, which in the early twentieth century was a popular place after dinner, was an elegant club with dancing to the Shelley Orchestra.’’

A safer bedmate?

Work by Lulu Wiley in the group show “Spring 2025 Solo Exhibition,’’ at the Southern Vermont Arts Center, through June 22.

Bucolic Manchester in 1913.

Silken Engineering at Tufts

Silkworms

Edited from a New England Council report

Tufts University’s Department of Biomedical Engineering is pursuing new projects in its Silklab.

“With the help of silkworms, the lab is developing various materials to be integrated into traditional clothing, surgical implants and other novel applications.

“The researchers are also developing a underwater adhesive for shark tagging, and small drones that can detect COVID-19 in the environment.

“‘I think that the directions we pick are the most surprising, which means that they open up something fundamental, something that you’ve never seen on the surface before, versus something that could have a high impact, like early detection of breast cancer,’ said Fiorenzo Omenetto, the director of the Silklab.

“‘I think it’s nice to connect the unconnectable, so there’s maybe the magic of trying to bring what was biological into the technical world.’

“Silklab has also helped develop startups that work in silk innovation, including Sofregen, which uses silk to repair damaged vocal cords, and Vaxess, which develops silk microneedles for vaccine delivery.’’

And furthermore

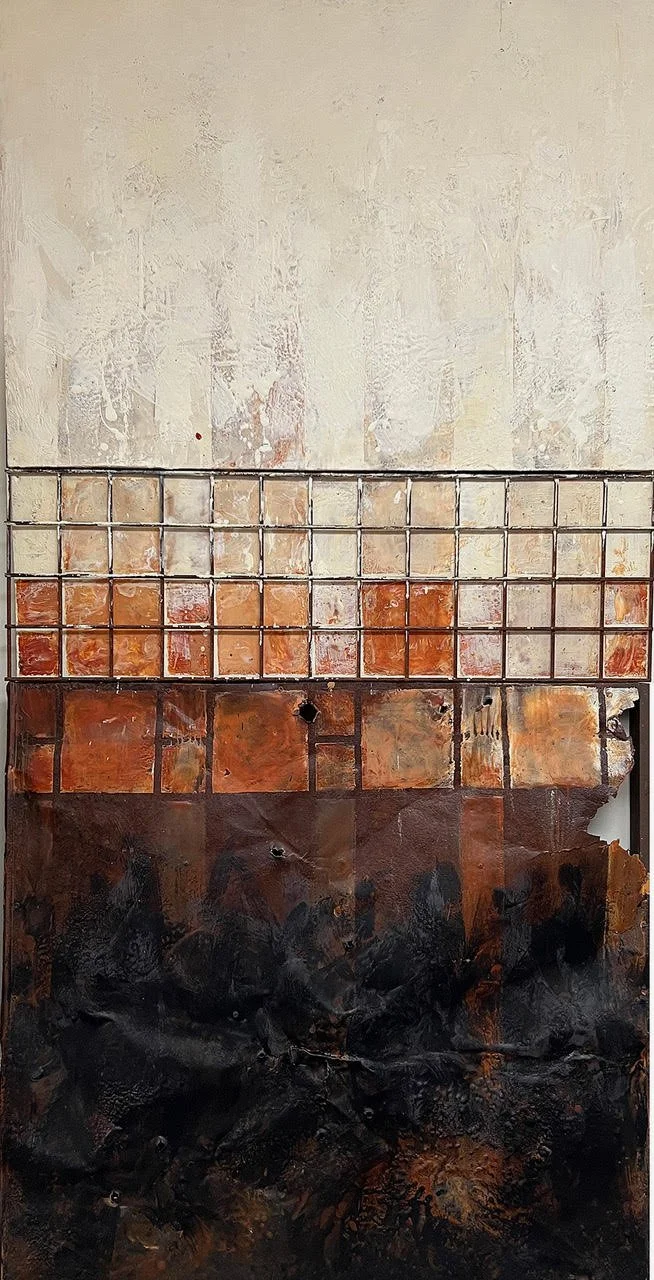

“Now and Then” (diptych with encaustic on the bottom metal and top wood with a metal grid), by Amherst, Mass.-based artist Sue Katz.

Karen Brown: Some painful Tradeoffs as concierge Medicine spreads Across primary care

Main Street in Northampton, Mass.

Text from Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

Michele Andrews had been seeing her internist in Northampton, a small city two hours west of Boston, for about 10 years. She was happy with the care, though she started to notice it was becoming harder to get an appointment.

“You’d call and you’re talking about weeks to a month,” Andrews said.

That’s not surprising, as many workplace surveys show the supply of primary-care doctors has fallen well below the demand, especially in rural areas such as western Massachusetts. But Andrews still wasn’t prepared for the letter that arrived last summer from her doctor, Christine Baker, at Pioneer Valley Internal Medicine.

“We are writing to inform you of an exciting change we will be making in our Internal Medicine Practice,” the letter read. “As of September 1st, 2024, we will be switching to Concierge Membership Practice.”

Concierge medicine is a business model in which a doctor charges patients a monthly or annual membership fee — even as the patients continue paying insurance premiums, copays, and deductibles. In exchange for the membership fee, doctors limit their number of patients.

Many physicians who’ve made the change said it resolved some of the pressures they faced in primary care, such as having too many patients to see in too short a time.

Andrews was floored when she got the letter. “The second paragraph tells me the yearly fee for joining will be $1,000 per year for existing patients. It’ll be $1,500 for new patients,” she said.

Although numbers are not tracked in any one place, the trade magazine Concierge Medicine Today estimates there are 7,000 to 22,000 concierge physicians in the U.S. Membership fees range from $1,000 to as high as $50,000 a year.

Critics say concierge medicine helps only patients who have extra money to spend on health care, while shrinking the supply of more traditional primary care practices in a community. It can particularly affect rural communities already experiencing a shortage of primary care options.

Andrews and her husband had three months to either join and pay the fee or leave the practice. They left.

“I’m insulted and I’m offended,” Andrews said. “I would never, never expect to have to pay more out of my pocket to get the kind of care that I should be getting with my insurance premiums.”

Baker, Andrews’ former physician, said fewer than half her patients opted to stay — shrinking her patient load from 1,700 to around 800, which she considers much more manageable. Baker said she had been feeling so stressed that she considered retiring.

“I knew some people would be very unhappy. I knew some would like it,” she said. “And a lot of people who didn’t sign up said, ‘I get why you’re doing it.’”

Patty Healey, another patient at Baker’s practice, said she didn’t consider leaving.

“I knew I had to pay,” Healey said. As a retired nurse, Healey knew about the shortages in primary care, and she was convinced that if she left, she’d have a very difficult time finding a new doctor. Healey was open to the idea that she might like the concierge model.

“It might be to my benefit, because maybe I’ll get earlier appointments and maybe I’ll be able to spend a longer period of time talking about my concerns,” she said.

This is the conundrum of concierge medicine, according to Michael Dill, director of workforce studies at the Association of American Medical Colleges. The quality of care may go up for those who can and do pay the fees, Dill said. “But that means fewer people have access,” he said. “So each time any physician makes that switch, it exacerbates the shortage.”

His association estimates the U.S. will face a shortage of 20,200 to 40,400 primary care doctors within the next decade.

A state analysis found that the percentage of residents in western Massachusetts who said they had a primary care provider was lower than in several other regions of the state.

Dill said the impact of concierge care is worse in rural areas, which often already experience physician shortages. “If even one or two make that switch, you’re going to feel it,” Dill said.

Rebecca Starr, an internist who specializes in geriatric care, recently started a concierge practice in Northampton.

For many years, she consulted for a medical group whose patients got only 15 minutes with a primary-care doctor, “and that was hardly enough time to review medications, much less manage chronic conditions,” she said.

When Starr opened her own medical practice, she wanted to offer longer appointments — but still bring in enough revenue to make the business work.

“I did feel a little torn,” Starr said. While it was her dream to offer high-quality care in a small practice, she said, “I have to do it in a way that I have to charge people, in addition to what insurance is paying for.”

Starr said her fee is $3,600 a year, and her patient load will be capped at 200, much lower than the 1,000 or even 2,000 patients that some doctors have. But she still hasn’t hit her limit.

“Certainly there’s some people that would love to join and can’t join because they have limited income,” Starr said.

Blue Canyon Primary Care offers “direct primary care” in Northampton for patients who pay $225 a month. Direct primary care is similar to concierge medicine but does not accept insurance. Patients must pay out-of-pocket and can seek reimbursement from their insurers afterward.(Karen Brown/New England Public Media)

Many doctors making the switch to concierge medicine say the membership model is the only way to have the kind of personal relationships with patients that attracted them to the profession in the first place.

“It’s a way to practice self-preservation in this field that is punishing patients and doctors alike,” said internal- medicine physician Shayne Taylor, who recently opened a practice offering “direct primary care” in Northampton.

The direct primary-care model is similar to concierge care in that it involves charging a recurring fee to patients, but direct care bypasses insurance companies altogether.

Taylor’s patients, capped at 300, pay her $225 a month for basic primary care visits — and they must have health insurance to cover care such as X-rays and medications, which her practice does not provide. But Taylor doesn’t accept insurance for any of her services, which saves her administrative costs.

“We get a lot of pushback because people are saying, ‘Oh, this is elitist, and this is only going to be accessible to people that have money,’” Taylor said.

But she said the traditional primary-care model doesn’t work. “We cannot spend so much time seeing so many patients and documenting in such a way to get an extra $17 from the insurance company.”

While much of the pushback on the membership model comes from patients and policy experts, some of the resistance comes from physicians.

Paul Carlan, a primary-care doctor who runs Valley Medical Group in western Massachusetts, said his practice is more stretched than ever. One reason is that the group’s clinics are absorbing some of the patients who have lost their doctor to concierge medicine.

“We all contribute through our tax dollars, which fund these training programs,” Carlan said.

“And so, to some degree, the folks who practice health care in our country are a public good,” Carlan said. “We should be worried when folks are making decisions about how to practice in ways that reduce their capacity to deliver that good back to the public.”

But Taylor, who has the direct primary-care practice, said it’s not fair to demand that individual doctors take on the task of fixing a dysfunctional health-care system.

“It’s either we do something like this,” Taylor said, “or we quit.”

Karen Brown is a reporter with Rhode Island Public Media.

This article is from a partnership that includes New England Public Media, NPR, and KFF Health News.

Baker/Furlanetto: Analyzing the real costs of various sources of energy

The Seabrook (N.H.) Nuclear Power Station.

Erin Baker is Distinguished Professor of Industrial Engineering and Faculty Director of The Energy Transition Institute, at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Paola Pimentel Furlanetto is a Ph.D. candidate in power systems, UMass Amherst.

Erin Baker receives funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), the U.S. Department of Energy and the Sloan Foundation

Paola Pimentel Furlanetto receives funding from NSF and Sloan Foundation.

AMHERST, Mass.

The Trump administration is working to lift regulations on coal-fired power plants in the hopes of making its energy less expensive. But while cost is one important aspect, utilities have a lot more to consider when they choose their power sources.

Different technologies play different roles in the power system. Some sources, like nuclear energy, are reliable but inflexible. Other sources, like oil, are flexible but expensive and polluting.

How utilities choose which power source to invest in depends in large part on two key aspects: price and reliability.

Power prices

One way to compare power sources is by their levelized cost of electricity. This shows how much it costs to produce one unit of electricity on average over the life of the generator.

The asset management firm Lazard has produced levelized cost of electricity calculations for the major U.S. electricity sources annually for years, and it has tracked a sharp decline in solar power costs in particular.

Coal is one of the more expensive technologies for utilities today, making it less competitive compared with solar, wind and natural gas, by Lazard’s calculations. Only nuclear, offshore wind and “peaker” plants, which are used only during periods of high electricity demand, are more expensive.

Land-based wind and solar power have the lowest estimated costs, far below what consumers are paying for electricity today. The National Renewable Energy Lab has found similar levelized costs for renewable energy, though its estimates for nuclear are lower than Lazard’s.

Upfront costs are also important and can make the difference for whether new power projects can be built, as the East Coast has seen lately.

Several offshore wind farms planned along the Northeast were canceled in recent years as costs rose due to inflation and supply-chain problems during the pandemic. Construction costs for the two newest nuclear generators built in the U.S. also rose considerably as the projects, both in the Southeast, faced delays.

Reliability and flexibility matter

But cost is not the whole story. Utilities must balance a number of criteria when investing in power sources.

Most important is matching supply and demand at every moment of the day. Due to the technical characteristics of electricity and how it flows, if the supply of electricity is even a little bit lower than the demand, that can trigger a blackout. This means power companies and consumers need generation that can ramp down when demand is low and ramp up when demand is high.

Since wind and solar generation depend on the wind blowing and the sun shining, these sources must be combined with other types of generation or with storage, such as batteries, to ensure the power grid has exactly as much power as it needs at all times.

Combining renewable energy and battery storage or both wind and solar can smooth out power supply dips and spikes. The Pine Tree Wind Farm and Solar Power Plant in the Tehachapi Mountains north of Los Angeles do both. Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Nuclear and coal are predictable and run reliably, but they are inflexible – they take time to ramp up and down, and doing so is expensive. Steam turbines are simply not built for flexibility. The multiple days it took to shut down Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant after an earthquake and tsunami damaged its backup power sources in 2011 illustrated the challenges and safety issues related to ramping down nuclear plants.

That means coal and nuclear aren’t as helpful on those hot summer days when utilities need a quick power increase to keep air conditioners running. These peaks may only happen a few days a year, but keeping the power on is crucial for human health and the economy.

In today’s energy system, the most flexible generation sources are natural gas and hydro. They can quickly adjust to meet changing electricity demand without the safety and cost concerns of coal and nuclear. Hydro can ramp in minutes but can only be built where large dams are feasible. The most cost-effective natural gas technology can ramp up within hours.

The big picture, by power source

Over the past two decades, natural gas use has risen quickly to overtake coal as the most common fuel for generating electricity in the U.S. The boom was largely driven by the growing use of fracking technology, which allowed producers to extract gas from rock and lowered the price.

Natural gas’s low price and high flexibility make it an attractive choice. Its rise is a large part of the reason coal use has plummeted.

But natural gas has its challenges. Natural gas requires pipelines to carry it across the country, leading to disruptive construction. As Texas saw during its February 2021 blackouts, natural gas equipment can also fail in extreme cold. And like coal, natural gas is a fossil fuel that releases greenhouse gases during combustion, so it is also helping to cause climate change and contributes to air pollution that can harm human health.

Nuclear power has been gaining interest recently since it does not contribute to climate change or local air pollution. It also provides a steady baseload of power, which is useful for computing centers as their demand does not fluctuate as much as households.

Of course, nuclear has ongoing challenges around the storage of radioactive waste and security concerns, and construction of large nuclear plants takes many years.

Coal is more flexible than nuclear, but far less so than natural gas or hydropower. Most concerning, coal is extremely dirty, emitting more climate-change-causing gases, and far more air pollution than natural gas.

Solar and wind have grown rapidly in recent years due to their falling costs and environmental benefits. According to Lazard, the cost of solar combined with batteries, which would be as flexible as hydropower, is well below the cost of coal with its limited flexibility.

However, wind and solar tend to take up a lot of space, which has led to challenges in local approvals for new sites and transmission lines. In addition, the sheer number of new projects is overwhelming power system operators’ ability to evaluate them, leading to increasing wait times for new generation to come online.

What’s ahead?

Utilities have another consideration: Federal, state and local governments can also influence and sometimes limit utilities’ choices. Tariffs, for example, can increase the cost of critical components for new construction. Permitting and regulations can slow down development. Subsidies can artificially lower costs.

In our view, policies that are done right can help utilities move toward more reliable and cost-effective choices which are also cleaner. Done wrong, they can be costly to the economy and the environment.

The wiccan coast

Wiccan priestess preaching.

Map by Sswonk

“New England has always been fabled for its eccentrics, and Salem’s witch history naturally began to attract religious iconoclasts….Wiccans began relocating to Boston’s North Shore, attracted by the ‘Salem’ mystique and hoping for a tolerant environment.’’

— David J. Skal (1952-2024), American cultural historian

When it finally arrives

“New England Landscape in Spring,’’ by George Henry Smillie (1840-1921), American painter and etcher.

Llewellyn King: As America turns its back on the World, the world will turn its back on America

Project connecting the Pacific and Atlantic via a Mexican railway system called the Railway of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. This will facilitate more Mexican trade with Europe and Asia, helping to reduce Mexico’s dependence on an increasingly unreliable United States.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

America has your back. That has been the message of U.S. foreign policy to the world’s vulnerable since the end of World War II.

That sense that America is behind you was a message for Europe against the threat of the Soviet Union and has been the implicit message for all threatened by authoritarian expansionism.

From the sophisticated in Western Europe to the struggling masses worldwide, America has always been there to help. Its mission has been to serve and, in its serving, to promote the American brand — freedom, democracy, capitalism, human rights — and to keep America a revered and special place.

America was there to arbitrate an end to civil war, to rush in with aid after a natural disaster, to provide food during a famine and medical assistance during an infectious disease outbreak. America was there with an open heart and open hand.

If you want to look at this in a transactional way, which is the currency of today, we gave but we got back. The ledger is balanced. For example, we sent forth America’s food surplus to where it was needed, from Pakistan to Ethiopia, and we opened markets to our farmers.

The world’s needs established a symbiotic relationship in which we gained reverence and prestige, and our values were exported and sometimes adopted.

President Trump has characterized us as victims of a venal world that has pillaged our goodwill, stolen our manufacturing and exploited our market. The fact is that when Trump took office in January, the United States had the best-performing economy in the world, and its citizens enjoyed the products of the world at reasonable prices. Inflation was a problem, but it was beginning to come down — and it wasn’t as persistent as it had been in Britain, for example.

Trump has painted a picture of a world where our manufacturing was somehow shanghaied and carried in the depth of night to Asia.

In fact, American businesses, big and small, sought out Asian manufacturing to avail themselves of cheap but talented labor, low regulation and a union-free environment.

Businesses will always go where the economic ecosystem favors them. The ecosystem offshore was as irresistible to us as it was to a tranche of European manufacturing.

The move to Asia hollowed out the old manufacturing centers of the Midwest and New England, but unemployment has remained low. Some industries, including farming, food processing and manufacturing, suffer labor shortages.

We need manufacturing that supports national security. That includes chips, heavy electrical equipment and other essential infrastructure goods. It doesn’t include a lot of consumer goods, from clothing to toys.

Former California Sen. S.I. Hayakawa, a Republican and a semanticist, said you couldn’t come up with the correct answer if your input was wrong, “no matter how hard you think.” Trump’s thinking about the world seems to be input-challenged.

The world isn’t changing only in how Trump has ordained but in other fundamental ones. Manufacturing in just five years will be very different. Artificial intelligence will be on the factory floor, in the planning and sales offices, and it will boost productivity. However, it won’t add jobs and probably will subtract them.

Trump would like to build a Fortress America with all that will involve, including higher prices and uncompetitive factories. While not undermining our position as the benefactor to the world, a better approach might be to build up North America and welcome Canada and Mexico into an even closer relationship. Canada shares much of our culture, is rich in raw materials, and has been an exemplary neighbor. Mexico is a treasure trove of talent and labor.

Rather than threatening Canada and belittling Mexico, a possible future lies in a collaborative relationship with our neighbors.

Meanwhile, Canada is looking for markets to the East and the West. Mexico, which is building a coast-to-coast railway to compete with the Panama Canal, is staking much on its new trade deal with the European Union.

Trump has sundered old relationships and old views of what is America’s place in the world order. No longer does the world have America at its back.

This is a time of choice: The Ugly American or the Great Neighbor.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Subscribe to Llewellyn King's File on Substack

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island.

Places to put them

“Memory Vessels,’’ by Caron Tabb, in her show “A Stone in My Shoe,’’ at ShowUp, Boston,

The gallery says:

“‘A Stone in My Shoe’ features a series of multimedia fiber installations that delve into themes of grief, memory and resilience. Drawing from the loss of her mother and the rising tide of antisemitism, Tabb weaves personal and collective narratives, visualizing internal struggles to inspire dialogue, reflection and empathy.’’