‘Their giddy arrival’

Apple tree in blossom

“I might have stayed in this world

forever without seeing them,

or feeling their giddy

arrival in my skin….”

—From “Flowering Tree,’’ by Nora Mitchell (born 1956), Vermont-based poet and teacher

Grand public architecture

From College Hill, Providence, starring the Rhode Island State House, designed by the celebrated New York firm of McKim, Mead and White and built in 1891-1901.

— Photo by William Morgan

‘The world as given’

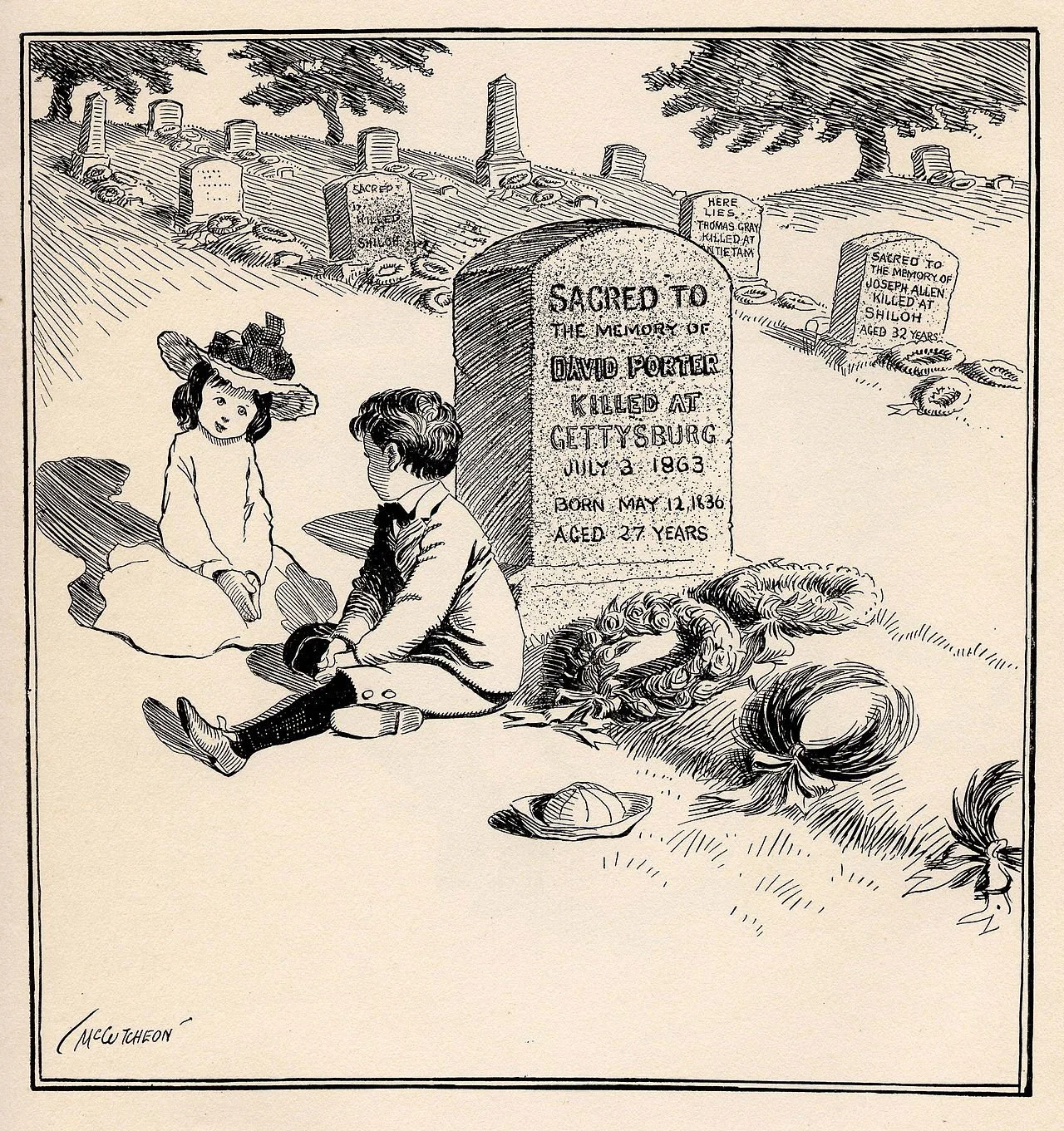

"On Decoration Day" (the earlier name of Memorial Day) political cartoon c. 1900 by John T. McCutcheon. Caption: "You bet I'm goin' to be a soldier, too, like my Uncle David, when I grow up."

“To say that war is madness is like saying that sex is madness: true enough, from the standpoint of a stateless eunuch, but merely a provocative epigram for those who must make their arrangements in the world as given.”

―John Updike (1932-2009), American novelist, short-story writer, essayist and literary and art critic. He spent most of his life on the Massachusetts North Shore.

Insatiable

“So Empty” (stoneware, porcelain, underglaze, nichrome wire, braided nylon thread, wood, paint), by Attleboro, Mass-based ceramic artist Erica Lynn Hood, in the group show “Earthworks, Tradition, Innovation,’’ at the Umbrella Arts Center, Concord, Mass., through June 23.

— Image courtesy of The Umbrella Arts Center

The galley says the show celebrates "the depth of history, tradition, and cultural expression in contemporary ceramics" and how modern ceramicists continue to push the boundaries of the medium. The show is juried by Ayumi Horie, a Maine-based potter who was the recipient of the 2022 Maine Craft Artist Award from the Maine Craft Association. She says: "What makes this show worth experiencing is the breadth of aesthetics, approaches, and ways of seeing a material that is at once so common and so underseen.’’

Memorial Day in World War II

Members of the American Legion (veterans) and Boy Scouts mark Memorial Day in tiny Ashland, Maine, in 1943. Most of the town’s young men were off serving the effort to win World War II. The town calls itself “Gateway to the North Maine Woods’’.

— Photo by John Collier for the Office of War Information

Adrienne Mayor: Wild animals know how to self-medicate

New Englanders should know that local plants were long used by the region’s Native Americans as medicines before the European colonists arrived. Above, a willow tree, whose bark contains salicylic acid, the active metabolite of aspirin, and used for millennia to relieve pain and reduce fever. Below, many Native American tribes used the leaves of sassafras as medicine to to treat wounds, acne, urinary disorders and high fevers.

.

When a wild orangutan in Sumatra recently suffered a facial wound, apparently after fighting with another male, he did something that caught the attention of the scientists observing him.

The animal chewed the leaves of a liana vine – a plant not normally eaten by apes. Over several days, the orangutan carefully applied the juice to its wound, then covered it with a paste of chewed-up liana. The wound healed with only a faint scar. The tropical plant he selected has antibacterial and antioxidant properties and is known to alleviate pain, fever, bleeding and inflammation.

The striking story was picked up by media worldwide. In interviews and in their research paper, the scientists stated that this is “the first systematically documented case of active wound treatment by a wild animal” with a biologically active plant. The discovery will “provide new insights into the origins of human wound care.”

Fibraurea tinctoria leaves and the orangutan chomping on some of the leaves. Laumer et al, Sci Rep 14, 8932 (2024), CC BY

To me, the behavior of the orangutan sounded familiar. As a historian of ancient science who investigates what Greeks and Romans knew about plants and animals, I was reminded of similar cases reported by Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, Aelian and other naturalists from antiquity. A remarkable body of accounts from ancient to medieval times describes self-medication by many different animals. The animals used plants to treat illness, repel parasites, neutralize poisons and heal wounds.

The term zoopharmacognosy – “animal medicine knowledge” – was invented in 1987. But as the Roman natural historian Pliny pointed out 2,000 years ago, many animals have made medical discoveries useful for humans. Indeed, a large number of medicinal plants used in modern drugs were first discovered by Indigenous peoples and past cultures who observed animals employing plants and emulated them.

What you can learn by watching animals

Some of the earliest written examples of animal self-medication appear in Aristotle’s “History of Animals” from the fourth century BCE, such as the well-known habit of dogs to eat grass when ill, probably for purging and deworming.

Aristotle also noted that after hibernation, bears seek wild garlic as their first food. It is rich in vitamin C, iron and magnesium, healthful nutrients after a long winter’s nap. The Latin name reflects this folk belief: Allium ursinum translates to “bear lily,” and the common name in many other languages refers to bears.

As a hunter lands several arrows in his quarry, a wounded doe nibbles some growing dittany. British Library, Harley MS 4751 (Harley Bestiary), folio 14v, CC BY

Pliny explained how the use of dittany, also known as wild oregano, to treat arrow wounds arose from watching wounded stags grazing on the herb. Aristotle and Dioscorides credited wild goats with the discovery. Vergil, Cicero, Plutarch, Solinus, Celsus and Galen claimed that dittany has the ability to expel an arrowhead and close the wound. Among dittany’s many known phytochemical properties are antiseptic, anti-inflammatory and coagulating effects.

According to Pliny, deer also knew an antidote for toxic plants: wild artichokes. The leaves relieve nausea and stomach cramps and protect the liver. To cure themselves of spider bites, Pliny wrote, deer ate crabs washed up on the beach, and sick goats did the same. Notably, crab shells contain chitosan, which boosts the immune system.

When elephants accidentally swallowed chameleons hidden on green foliage, they ate olive leaves, a natural antibiotic to combat salmonella harbored by lizards. Pliny said ravens eat chameleons, but then ingest bay leaves to counter the lizards’ toxicity. Antibacterial bay leaves relieve diarrhea and gastrointestinal distress. Pliny noted that blackbirds, partridges, jays and pigeons also eat bay leaves for digestive problems.

A weasel wears a belt of rue as it attacks a basilisk in an illustration from a 1600s bestiary. Wenceslaus Hollar/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Weasels were said to roll in the evergreen plant rue to counter wounds and snakebites. Fresh rue is toxic. Its medical value is unclear, but the dried plant is included in many traditional folk medicines. Swallows collect another toxic plant, celandine, to make a poultice for their chicks’ eyes. Snakes emerging from hibernation rub their eyes on fennel. Fennel bulbs contain compounds that promote tissue repair and immunity.

According to the naturalist Aelian, who lived in the third century BCE, the Egyptians traced much of their medical knowledge to the wisdom of animals. Aelian described elephants treating spear wounds with olive flowers and oil. He also mentioned storks, partridges and turtledoves crushing oregano leaves and applying the paste to wounds.

The study of animals’ remedies continued in the Middle Ages. An example from the 12th-century English compendium of animal lore, the Aberdeen Bestiary, tells of bears coating sores with mullein. Folk medicine prescribes this flowering plant to soothe pain and heal burns and wounds, thanks to its anti-inflammatory chemicals.

Ibn al-Durayhim’s 14th-century manuscript “The Usefulness of Animals” reported that swallows healed nestlings’ eyes with turmeric, another anti-inflammatory. He also noted that wild goats chew and apply sphagnum moss to wounds, just as the Sumatran orangutan did with liana. Sphagnum moss dressings neutralize bacteria and combat infection.

Nature’s pharmacopoeia

Of course, these premodern observations were folk knowledge, not formal science. But the stories reveal long-term observation and imitation of diverse animal species self-doctoring with bioactive plants. Just as traditional Indigenous ethnobotany is leading to lifesaving drugs today, scientific testing of the ancient and medieval claims could lead to discoveries of new therapeutic plants.

Animal self-medication has become a rapidly growing scientific discipline. Observers report observations of animals, from birds and rats to porcupines and chimpanzees, deliberately employing an impressive repertoire of medicinal substances. One surprising observation is that finches and sparrows collect cigarette butts. The nicotine kills mites in bird nests. Some veterinarians even allow ailing dogs, horses and other domestic animals to choose their own prescriptions by sniffing various botanical compounds.

Mysteries remain. No one knows how animals sense which plants cure sickness, heal wounds, repel parasites or otherwise promote health. Are they intentionally responding to particular health crises? And how is their knowledge transmitted? What we do know is that we humans have been learning healing secrets by watching animals self-medicate for millennia.

Adrienne Mayor is a research scholar in Classics and History and Philosophy of Science at Stanford University

Adrienne Mayor does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Melissa Bright: Rethinking ways to prevent sexual abuse of children

Children playing ball games, Roman artwork, 2nd Century AD.

DURHAM, N.H.

Child sexual abuse is uncomfortable to think about, much less talk about. The idea of an adult engaging in sexual behaviors with a child feels sickening. It’s easiest to believe that it rarely happens, and when it does, that it’s only to children whose parents aren’t protecting them.

This belief stayed with me during my early days as a parent. I kept an eye out for creepy men at the playground and was skeptical of men who worked with young children, such as teachers and coaches. When my kids were old enough, I taught them what a “good touch” was, like a hug from a family member, and what a “bad touch” was, like someone touching their private parts.

But after nearly a quarter-century of conducting research – 15 years on family violence, another eight on child abuse prevention, including sexual abuse – I realized that many people, including me, were using antiquated strategies to protect our children.

As the founder of the Center for Violence Prevention Research, I work with organizations that educate their communities and provide direct services to survivors of child sexual abuse. From them, I have learned much about the everyday actions all of us can take to help keep our children safe. Some of it may surprise you.

First, my view of what constitutes child sexual abuse was too narrow. Certainly, all sexual activities between adults and children are a form of abuse.

But child sexual abuse also includes nonconsensual sexual contact between two children. It includes noncontact offenses such as sexual harassment, exhibitionism and using children to produce imagery of sexual abuse. Technology-based child sexual abuse is rising quickly with the rapid evolution of internet-based games, social media, and content generated by artificial intelligence. Reports to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children of online enticements increased 300% from 2021 to 2023.

My assumption that child sexual abuse didn’t happen in my community was wrong too. The latest data shows that at least 1 in 10 children, but likely closer to 1 in 5, experience sexual abuse. Statistically, that’s at least two children in my son’s kindergarten class.

Child sexual abuse happens across all ethnoracial groups, socioeconomic statuses and all gender identities. Reports of female victims outnumber males, but male victimization is likely underreported because of stigma and cultural norms about masculinity.

I’ve learned that identifying the “creepy man” at the playground is not an effective strategy. At least 90% of child sexual abusers know their victims or the victims’ family prior to offending. Usually, the abuser is a trusted member of the community; sometimes, it’s a family member.

In other words, rather than search for a predator in the park, parents need to look at the circle of people they invite into their home.

To be clear, abuse by strangers does happen, and teaching our kids to be wary of strangers is necessary. But it’s the exception, not the norm, for child sexual abuse offenses.

Most of the time, it’s not even adults causing the harm. The latest data shows more than 70% of self-reported child sexual abuse is committed by other juveniles. Nearly 1 in 10 young people say they caused some type of sexual harm to another child. Their average age at the time of causing harm is between 14 and 16.

Drastic changes in behavior – either positive or negative – can be an indication of potential sexual abuse.

Now for a bit of good news: The belief that people who sexually abuse children are innately evil is an oversimplification. In reality, only about 13% of adults and approximately 5% of adolescents who sexually harm children commit another sexual offense after five years. The recidivism rate is even lower for those who receive therapeutic help.

By contrast, approximately 44% of adults who commit a felony of any kind will commit another offense within a year of prison release.

What parents can do

The latest research says uncomfortable conversations are necessary to keep kids safe. Here are some recommended strategies:

Avoid confusing language. “Good touches” and “bad touches” are no longer appropriate descriptors of abuse. Harmful touches can feel physically good, rather than painful or “bad.” Abusers can also manipulate children to believe their touches are acts of love.

The research shows that it’s better to talk to children about touches that are “OK” or “not OK,” based on who does the touching and where they touch. This dissipates the confusion of something being bad but feeling good.

These conversations require clear identification of all body parts, from head and shoulders to penis and vagina. Using accurate anatomical labels teaches children that all body parts can be discussed openly with safe adults. Also, when children use accurate labels to disclose abuse, they are more likely to be understood and believed.

One tip: Teach children the anatomical names for their body parts, not “code” or “cute” names.

Encourage bodily autonomy. Telling my children that hugs from family members were universally good touches was also wrong. If children think they have to give hugs on demand, it conveys the message they do not have authority over their body.

Instead, I watch when my child is asked for a hug at family gatherings – if he hesitates, I advocate for him. I tell family members that physical touch is not mandatory and explain why – something like: “He prefers a bit more personal space, and we’re working on teaching him that he can decide who touches him and when. He really likes to give high-fives to show affection.” A heads-up: Often, the adults are put off, at least initially.

In my family, we also don’t allow the use of guilt to encourage affection. That includes phrases like: “You’ll make me sad if you don’t give me a hug.”

Promote empowerment. Research on adult sexual offenders found the greatest deterrence to completing the act was a vocal child – one who expressed their desire to stop, or said they would tell others.

Monitor your child’s social media. Multiple studies show that monitoring guards against sexting or viewing of pornography, both of which are risk factors for child sexual abuse. Monitoring can also reveal permissive or dangerous sexual attitudes the child might have.

Talk to the adults in your circle. Ask those watching your child how they plan to keep your child safe when in their care. Admittedly, this can be an awkward conversation. I might say, “Hey, I have a few questions that might sound weird, but I think they’re important for parents to ask. I’m sure my child will be safe with you, but I’m trying to talk about these things regularly, so this is good practice for me.” You may need to educate them on what the research shows.

Ask your child’s school what they’re doing to educate students and staff about child sexual abuse. Many states require schools to provide prevention education; recent research suggests these programs help children protect themselves from sexual abuse.

Talk to your child’s sports or activity organization. Ask what procedures are in place to keep children safe. This includes their screening and hiring practices, how they train and educate staff, and their guidelines for reporting abuse. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides a guide for organizations on keeping children safe.

Rely on updated research. Finally, when searching online for information, look for research that’s relatively recent – dated within the past five years. These studies should be published in peer-reviewed journals.

And then be prepared for a jolt. You may discover the conventional wisdom you’ve clung to all these years may be based on outdated – and even harmful – information.

Melissa Bright is founder and executive director of the Center for Violence Prevention Research and an affiliate faculty member at the Crimes Against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire

She receives funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Childhood Foundation (via work with Stop it Now!).

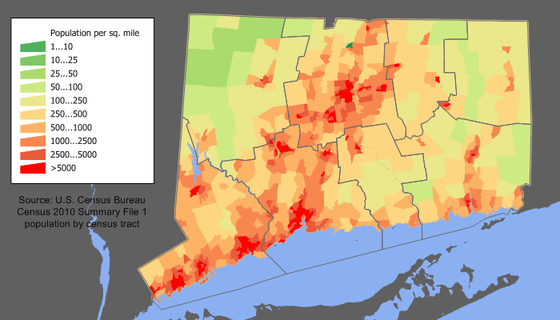

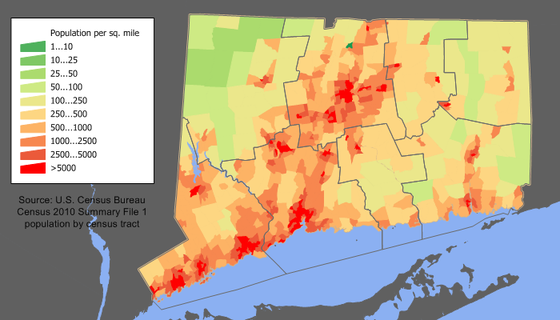

Chris Powell: If you chant ‘Trump!’ enough, Conn. Democrats’ problems vanish

MANCHESTER, Conn.

While Donald Trump can be intemperate, reckless, and megalomaniacal, that is not why he has been so damaging to politics in Connecticut. Trump is most damaging to politics here because he has provided an excuse for so many members of the state's majority party, the Democrats, as well as their allies in the news media, to avoid serious discussion of the many failures of public policy essentially just by chanting: "Trump! Trump! Trump!"

Connecticut has big problems that have not been addressed seriously: education and the declining skill level of the rising workforce, worsening poverty, prohibitive housing prices, state government's indebtedness, a lack of economic and population growth, racial segregation, and taxes that are high even though none of these problems has been alleviated much if at all.

Not that the minority party, the Republicans, necessarily would do much better with these problems. Indeed, the most recent 16 years of Republican state administration (1995-2011) differed from Democratic administration only insofar as taxes didn't go up as much as they might have under a Democratic administration. Of course that's something, but under Republican administration Connecticut's downward trends weren't halted, much less reversed. Connecticut didn't get more value from its government.

While Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee for president, is leading the presumptive Democratic nominee, President Biden, in the recent national polls, nobody expects Trump to carry Connecticut. The state is too Democratic, and just chanting "Trump! Trump! Trump!" here will probably distract enough from the big national issues -- inflation and the economy in general, illegal immigration, and the expensive and unnecessary proxy war in Ukraine and the danger that it will erupt into a European war or even a world war. (A currency war arising in part from the Ukraine war is already being waged.)

The Democratic chant will help sustain the political status quo in the state but it won't make Connecticut great again. For that to happen, many mistaken premises of policy will have to be challenged.

xxx

WHY GO TO SCHOOL?: Last week Gov. Ned Lamont joined a White House conference about chronic absenteeism from school, a problem nationally as well as in Connecticut. Among the participants were U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona, formerly Meriden's school superintendent and Connecticut's education commissioner.

They discussed the slight success in getting children to attend school more often by having school employees call or visit the homes of the chronically absent and asking parents what the problem is and if government can help them solve it.

Warning parents that not getting their children get to school is neglect is not planned. The politically correct presumption is that parents, especially single parents, really shouldn't be held responsible for themselves and their children. Many neglectful parents probably sense this presumption and feel excused.

Connecticut's elected officials should look deeper into the problem, especially since student proficiency in the state has been declining for years. They should ask: What exactly is the incentive for children to go to school today and for parents to get them there?

In the old days social pressure helped get children to school and to learn. For failure to learn risked the embarrassment of being held back a grade.

But no more. For Connecticut's main educational policy long has been social promotion: All students are promoted regardless of academic failure, in the belief that being held back is too damaging to a child's self-esteem -- as if failure to learn is not more damaging when a child grows up.

Meanwhile, the decline in the skill level of Connecticut students, and thus the decline in their ability to support themselves, is being met with more government subsidies for them as impoverished adults, so neglecting one's education is less costly to the individual and more costly to taxpayers.

In the old days most people thought education was crucial to a better life. Today many people seem to think otherwise. So chronic absenteeism may continue until something changes that thinking. Politically correct as it may be, asking negligent parents nicely isn't likely to help much.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years. (CPowell@cox.net) .

The Bay State’s most educated place

Recreation in Boston’s Seaport District.

Boston Convention and Exhibition Center’s entry canopy. The center brings throngs to the Seaport District.

—Photo by Generaltso

Looking north up the Fort Point Channel in the Seaport District. The channel, once infamous for its pollution, in recent decades has been much cleaned up. You’ll often see kayakers on it.

— Photo by Shorelander

Edited from a Boston Guardian article.

(New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian)

Not only is the Seaport District the wealthiest neighborhood in Boston and the most expensive place in the city in which to buy or rent, it’s also the most highly educated community in the entire state.

According to data compiled by The Boston Business Journal, 93.1 percent of adult residents have a college degree or higher.

The only other city neighborhood in the top 20 statewide is the Fenway, with 83.7 percent of adult inhabitants with at least a college degree. The Fenway ranks number 13.

The top 10 smartest areas are:

Seaport 93.1%

Waban 90.1%

Wellesley Hills 89.7%

Dover 87.7%

Lincoln 87.3%

Newton Highlands 86.8%

Harvard Square (Cambridge) 86.7%

Newton Centre 86.2%

Needham 84.9%

Coolidge Corner (Brookline) 84.6%

Rhode Island might soon ban captive hunting

Female white-tailed deer (a very common species in New England) with tail in alarm posture. There’s worry that bringing in elk and other species from other parts of American could introduce diseases.

— Photo by D. Gordon E. Robertson

Excerpted from an ecoRI News article by Rob Smith

“Five years after the plan was first introduced, state lawmakers are on the cusp of banning captive hunting practices in Rhode Island.

“Also known as ‘canned hunting,’ captive hunting refers to the practice of importing wild animals into a specific, fenced-in location for the intended purpose of hunting game that, in theory, cannot escape. Critics of the practice have argued that legalizing captive hunting would be a backdoor way into introducing wild game and even diseases that currently have no presence in Rhode Island, and would interrupt local hunters’ longstanding free-chase traditions….

“Identical bans (S2732A/H7294A) were introduced in the House and Senate earlier this year. ..

Tres gay in Hartford

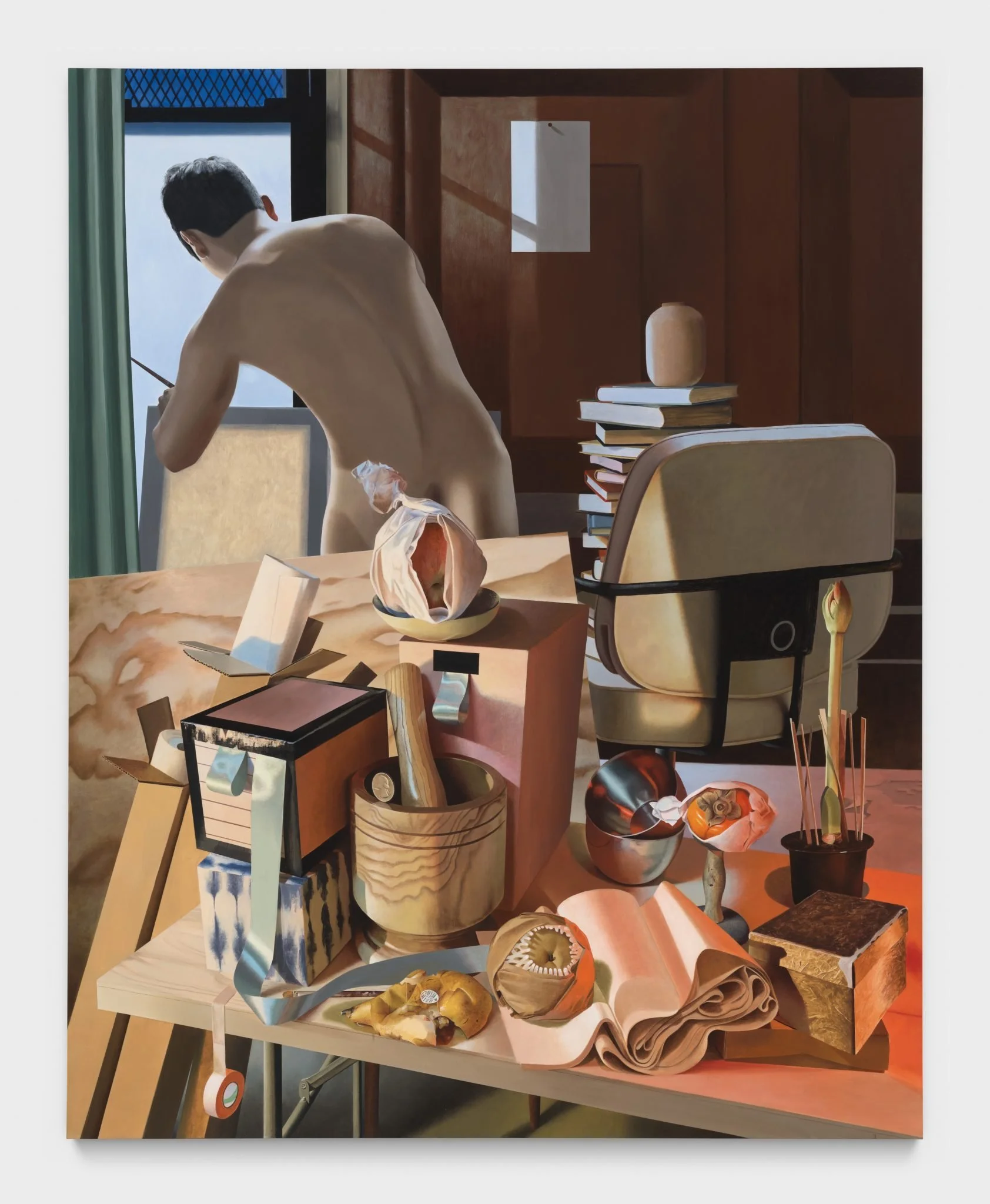

“Studio Still Life” (acrylic on wood panel), by New York painter Kyle Dunn, in his show Matrix 194, at the Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art, Hartford, June 7-Sept. 1

- Courtesy of the Artist and P·P·O·W, New York

- Photo by JSP Art Photography

The museum says:

“Kyle Dunn’s luminous paintings dramatize themes of intimacy and alienation. In alluring domestic scenes, men perform everyday rituals against the backdrop of the big city, whose glow shines through the windows of their small apartments. Some of his composite figures sit in quiet contemplation, while others are seemingly caught during romantic encounters. Spatially ambiguous settings collapse interior and exterior worlds—both physical and psychological—inviting us to question the boundaries between public and private, individual and collective.’’

Why to be a vegan?

“Prosciutta” (clay, glaze, acrylic and epoxy), by Boston area artist Joe Caruso, in the show DIG, at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., through Aug. 11

— Image courtesy of Art Complex Museum

The museum says that DIG features the work of Joe Caruso, Jennifer Liston Munson, Palamidessi and Marsha Odabashian in a show that "recalls traditions, events, and customs across a range of cultures.’’ The artists in explore "what makes us human" by exploring the past and how it connects to the future. The show "values, preserves and calls attention to what came before so we can learn from the past as we cope with the present and prepare for the future."

Llewellyn King: You’ll feel better with a bit of silken style around your neck

Archibald Cox (1912-2004), who served as Watergate scandal special prosecutor, solicitor general and Harvard Law School professor, wearing, as usual, a bow tie — a popular accessory of New England WASP’s.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I admire Ben Mankiewicz, host of Turner Classic Movies. He is the man we all think we are in our dreams: handsome, urbane, authoritative and oh-so charming — a member of one of the great families of film, an aristocrat of that realm.

I would like to look like Ben; his job is appealing, too.

But wait, Ben has suffered a savage downfall. He isn’t the man he used to be to me. I nearly fell off the couch when I saw Ben, an inspiration to men, introducing a movie without his necktie.

Yes, Ben was open-collared in a suit, looking a little like an unmade bed, which is what most men look like when pursuing the current fashion of no necktie.

Shock Horror! Another bastion of masculinity has fallen.

The problem — and I aver this to be an unassailable truth — is men wearing dress shirts without ties look less than their best. If they have a bit of age on them, a lot less than their best.

The dress shirt, which hasn’t been replaced, is designed for a necktie, long or in a bow. Without them men look diminished, incomplete, as though they had to leave the house with no time to finish dressing.

Let me state that the necktie is indeed a useless piece of clothing, like other dress items of the past: spats, watch chains and detached collars. The passing of none of these do I regret – but ties? Cry, the lost masculine adornment of yesteryear.

The necktie was something a man could glory in. Tying a long tie and throwing the long end over the short end always gave me the same feeling as mounting my horse; when my right leg cleared the saddle, I knew something good was going to happen. A great day in the Virginia countryside usually.

Ties were something to treasure; fine silk, great patterns, elegance written with restraint. Just long enough, just obvious enough, conveying refinement and masculine savoir faire.

Now men are running around open-necked in shirts that weren’t designed to be worn that way.

Have a care for the great names in ties, those who saved us on Father’s Day, Christmas and birthdays, are losing money or gone to other pursuits.

Have a care for Hermes, Liberty, Tyrwhitt, Brioni, Fumagalli, Brooks Brothers and all those who created lovely things for the neck out of silk, finely woven wool or linen.

Just the sight of the box lit up the male face, ensuring the giver some future preferment or an extra helping at the table. The power of the tie was formidable — as Omar Khayyam, the Persian poet, might have said, it could transmute life’s leaden metal into gold.

At least it kept Dad smiling through some de rigueur family events. Ever noticed how he slipped off to the bathroom not to engage the porcelain but to admire himself in the mirror with the new gift around his neck?

Not so long ago, great restaurants had spare ties for guests who showed up without them. Now that is over.

The last holdout I know of is the Metropolitan Club in Washington. I have been to two events there recently and the hosts thought it wise to advise their guests on dress etiquette: ties and no white-soled shoes. But no cravats or ascots as well. Strange.

I am hoping the cravat or its cousin the ascot will come back vigorously. It will save those master craftspeople who dyed silk, wove wool and shaped their handiwork over canvas to adorn men’s necks of no practical value but so dressy, so uplifting, so defining.

Give a cravat and tell the man in your life or your father, “You look like David Niven.”

Come to think of it, I bet that Ben Mankiewicz looks stupendous wearing a cravat.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Never-ending work

“Mending Nets, F/V Miss Trish II” (photograph), by Paul Cary Goldberg, at Manship Arts and Residence, Gloucester, Mass.

Why they stayed

The path along the Charles River on the Esplanade, in Boston.

—Photo by Ingfbruno

—Photo by Milos Milosevic

Kim Stanley Robinson (born 1952), American writer

John O. Harney: The Rose Kennedy Greenway bursts into bloom

The Rose Kennedy Greenway

Some sights on the Greenway:

BOSTON

I began volunteering as a phenologist on the Rose Kennedy Greenway, in downtown Boston, in spring 2023 and returned a few weeks ago for the 2024 season.

Peppermint-striped tulips were flowering along Pearl Street. Grape hyacinths create purple blankets; anemones whitish carpets. Hellebores that made an early spring show with dusty green-white and pink flowers were already fading. In one spot, it looked like a resting animal has flattened a bed of irises and allium.

Last year, all narcissuses were daffodils to my hardly trained eye. This year, I think I was seeing poeticus with white petals and yellow and reddish-outlined centers, sagitta with yellow double flowers around an orange tube and pheasants eye with its complex yellow and orange center. But I could be wrong.

Many plants were leafing but not yet flowering: irises, alliums, yellow- and red-twig dogwoods, lamb’s ear, roses, penstemon leafing purplish, dracunculus, astilbes, peonies, tickseed in a tough place along Purchase Street, nepeta, grasses near the tunnel vent still yellowish but with a few strands of green, achillea, aruncus and hosta shoots I’ve watched turn from young purplish shoots to fat green leaves reminiscent of a Rousseau painting. Few veggies or fruits visible. No sunflowers yet.

(By the way, in my old job as the executive editor of the New England Journal of Higher Education I was in charge of editorial style rules … things such as when to capitalize words, including names of plants I suppose. It always seemed too arbitrary, and, in retirement, I don’t bother.)

At the corner of Congress Street, I notices a mat of creeping blue phlox with its many light blue-purplish flowers—not, to my eye at least, the pink phlox associated with April 2024’s pink moon.

Speaking of such connections, serviceberry shrubs (also known as shadbushes) had flowered, mirroring the season when shad fish run up New England rivers and, for me, the promise of the delicious season of shad roe.

Jumping out to me on Parcel 21 was a humble dandelion. I note that, sure, it’s a pest, but it’s flowering full yellow, so it gets a 3 in the Greenway ranking system that I’ve never quite got my head around, as they say. The “best” rank among 1 to 5 is 3, not the lowest or highest, but 3 for full flower … peak.

A few other observations …

Maybe it’s the natural magnificence of the Greenway that somehow makes man-made signs catch my eye. Even the troubles of the world pierce the serenity of the park. Take the spot near the North End where a Priority Mail sticker on a park sign reads: “FROM: POWER TO THE RESISTANCE TO: GLOBALIZE THE INTIFADA’’.

Then the welcome reminder of “No mow May on the Greenway … The Greenway Conservancy is participating in Plantlife’s No Mow May initiative to support local pollinators, reduce lawn inputs, and grow healthier lawns. Certain areas of the Greenway will not be mowed in May.” A noble goal for homeowners too.

Nice to see a rare nametag on the Greenway identifying the good-looking and great-smelling Koreanspice viburnum. I had proposed such tagging last year in my piece on A Volunteer Life. Undoubtedly, others made similar suggestions. Still, I naively congratulated myself for any role in the tag, as two houseless people tried to tell me that there are apps on the market that ID plants. Immersed in my headphones, I reacted dismissively. Like a jerk, really. Quickly realizing my rudeness, I returned and apologized. These gardens are theirs more than mine.

With the helpful tips from the houseless on my mind and my interest in signs piqued, I also noticed for the first time, in Parcel 22, a green sign reading: “PARK CLOSED, 11 PM – 7 AM Trespassers will be prosecuted.”

With its tunnel vent, Parcel 22 is a big part of my Greenway life partly for its proximity to the park’s edible and pollinator gardens and Dewey Square and the Red Line plaza. The tunnel vent holds the Greenway mural. A sign reads: “What has this mural meant to you?” A mailbox is supplied for reader comments. One of the recent murals depicted a youth from the city, who critics insisted was a Middle Eastern terrorist. (Murals are dangerous business in New England. See here and here.)

And now to presumably dazzle the Greenway: colorful coneflowers, sturdy Joe Pye weeds, beebalm, furry salvia, white fringe trees, flowering black elderberries and hydangeas.

Jay L. Zagorsky: What about all that small change we leave at airports?

TSA officer at airport with a tray of prohibited items.

BOSTON

Should the U.S. get rid of pennies, nickels and dimes? The debate has gone on for years. Many people argue for keeping coins on economic-fairness grounds. Others call for eliminating them because the government loses money minting low-value coins.

One way to resolve the debate is to check whether people are still using small-value coins. And there’s an unlikely source of information showing how much people are using pocket change: the Transportation Security Administration, or TSA. Yes, the same people who screen passengers at airport checkpoints can answer whether people are still using coins – and whether that usage is trending up or down over the years.

Each year, the TSA provides a detailed report to Congress showing how much money is left behind at checkpoints. A decreasing amount of change would suggest fewer people have coins in their pockets, while a steady or increasing amount indicates people are still carrying coins.

The latest TSA figure shows that during 2023, air travelers left almost US$1 million in small change at checkpoints. This is roughly double the amount left behind in 2012.

At first glance, this suggests more people are carrying around and using coins. But as a university researcher who studies both travel and money usage – as well as a keen observer of habits while lining up at airport checkpoints – I know the story is more complicated than these numbers suggest.

What gets left behind?

More than 2 million people fly each day in the U.S., passing through hundreds of airport checkpoints manned by the TSA. Each flyer going through a checkpoint is asked to place items from their pockets such as wallets, phones, keys and coins in either a bin or their carry-on bag. Not everyone remembers to pick up all their items on the other side of the scanner. About 90,000 to 100,000 items are left behind each month, the TSA estimates.

For expensive or identifiable items such as cellphones, wallets and laptops, the TSA has a lost-and-found department. For coins and the occasional paper bills that end up in the scanner bins, TSA has a different procedure. It collects all that money, catalogs the amount and periodically deposits it into a special account that the TSA uses to improve security operations.

That money adds up, with travelers leaving behind almost $10 million in change over the past 12 years.

The amount of money left varies by airport. JFK International Airport in New York City is consistently in one of the top slots for most money lost, with travelers leaving almost $60,000 behind in 2022. Harry Reid International Airport, which serves Las Vegas, also sees a large amount of money left behind. Love Field in Dallas, headquarters of Southwest Airlines, is often near the bottom of the list, with only about $100 lost in 2022.

People lose money while going through security for a few reasons. First, some cut it close getting to the airport, and in their rush to avoid missing their plane, they don’t pick up everything after screening. Second, sometimes TSA lines are exceptionally long, leaving people to again scramble to make up time. And finally, TSA checkpoints are often confusing and noisy places, especially for new or infrequent travelers. Making it more confusing is that some airports have bins featuring advertisements, which distract travelers who only quickly glance to check for all their items.

How much is lost?

TSA keeps careful track of how much is lost because the agency is allowed to keep any unclaimed money left behind at checkpoints. TSA records show people left behind half a million dollars in 2012. This rose to almost a million in 2018. The drop in travel due to the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the figure back to half a million in 2020. In 2023, people left $956,000.

These raw figures need two adjustments to accurately track trends in coins lost. First, the numbers need to be adjusted for inflation. From 2012 to 2023, the consumer price index rose by 33%. This means a dollar of change in 2012 purchased one-third more than it did 12 years later.

Second, the number of people flying and passing through TSA screening has changed dramatically over time. In 2012, about 638 million people went through the checkpoints. By 2023, that had risen to 859 million people, which is about 1,000 people every 30 seconds across the entire U.S. when airports and checkpoints are open.

Adjusting for both inflation and the number of people screened shows no change in the amount of money lost. My calculations show back in 2012 about $1.10 in coins was lost for every 1,000 people screened. In 2023, about one penny more, or $1.11, was lost per 1,000.

The peak year for money being lost was 2020, when $1.80 per 1,000 people was left behind. This was likely due to people not wanting to touch objects out of misplaced fear they could contact COVID-19. During the pandemic, people in general carried less money.

The world is increasingly using electronic payments. The data from TSA checkpoints, however, clearly shows people are carrying coins at roughly the same rate as back in 2012. This suggests Americans are still using physical money, at least for making small payments – and that the drive to get rid of pennies, nickels and dimes should hold off a while longer.

Jay L. Zagorsky is associate professor of markets, public policy and law at Boston University.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.

Chased by spring

‘The Road North,’’ by Nora S. Unwin (1907-1982), at the Monadnock Center for History and Culture, Peterboro, N.H., through Sept. 28.

The gallery says:

Artist, engraver, illustrator and teacher, Nora S. Unwin had a long and successful career in her native England and her adopted home in New Hampshire. This retrospective exhibition features more than 80 works spanning her 60-year career.

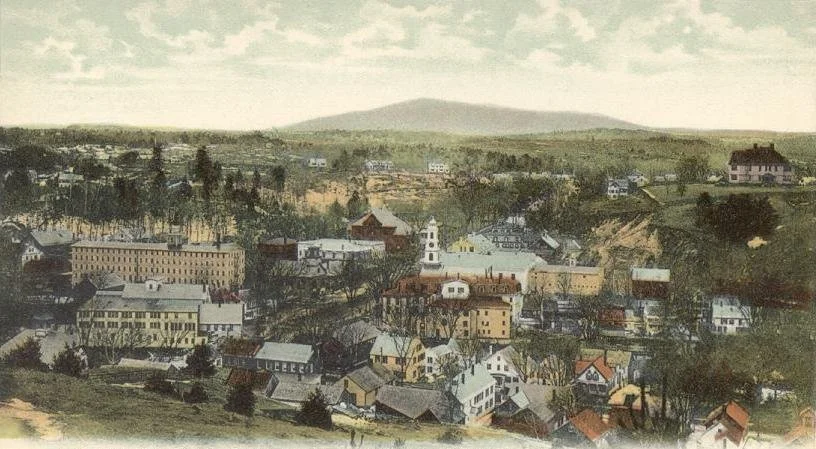

Peterboro in 1907.

Jessica Garcia: Insurance ‘bluelining’ for the vulnerable as they face disasters spawned by global warming

Flooding in Montpelier, Vt. on July11, 2023.

Via OtherWords.org

In an era of climate disasters, Americans in vulnerable regions will need to rely more than ever on their home insurance. But as floods, wildfires and severe storms become more common, a troubling practice known as “bluelining” threatens to leave many communities unable to afford insurance — or obtain it at any price.

Bluelining is an insidious practice with similarities to redlining — the notorious past government-sanctioned practice of financial institutions denying mortgages and credit to Black and brown communities, which were often marked by red lines on map.

These days, financial institutions are now drawing “blue lines” around many of these same communities, restricting such services as insurance based on environmental risks. Even worse, many of those same institutions are bankrolling those risks by funding and insuring the fossil fuel industry.

Originally, bluelining referred to blue-water flood risks, but it now includes such other climate-related disasters as wildfires, hurricanes, and severe thunderstorms, all of which are driving private-sector decisions. (Severe thunderstorms, in fact, were responsible for about 61 percent of insured natural catastrophe losses in 2023.)

In the case of property insurance, we’re already seeing insurers pull out of entire states, such as California and Florida. The financial impacts of these decisions are considerable for everyone they affect — and often fall hardest on those in low-income and historically disadvantaged communities.

A Redfin study from 2021 illustrated that areas previously affected by redlining are now also those prone to flooding and higher temperatures, a problem compounded by poor infrastructure that fails to mitigate these risks. This overlap is not a coincidence but a further consequence of systemic discrimination and disinvestment.

This financial problem exists no matter where you live. In 2024, the national average home-insurance cost has risen about 23 percent above the cost of similar coverage last year. Homeowners across more and more states are left grappling with soaring premiums or no insurance options at all. And the lack of federal oversight means there is little uniformity or coordination in addressing these retreats.

This situation will demand a radical rethink of how we approach investing in our communities based on climate risks. For one thing, financial institutions must pivot from funding fossil fuel expansion to investing in renewable energy, natural climate solutions, and climate resilience, including infrastructure upgrades.

What about communities in especially vulnerable areas?

One strategy is community-driven relocation and managed retreat. By relocating communities to low-risk areas, we not only safeguard them against immediate physical dangers but also against ensuing financial hardships. Additionally, preventing development in known high-risk areas can significantly decrease financial instability and economic losses from future disasters.

As part of this strategic shift, financial policies must be realigned. We need regulations that compel financial institutions to manage and mitigate financial risk to the system and to consumers. We also need them to invest in affordable housing development that is energy-efficient, climate-resilient, and located in areas less susceptible to climate change in the mid- to long-term.

Meanwhile, green infrastructure and stricter energy efficiency and other resilience-related building codes can serve as bulwarks against extreme temperatures and weather events.

The challenge of bluelining offers us an opportunity to forge a path towards a more resilient and equitable society. We owe it to the future generations to do more than just adapt to climate change. We also need to confront and overhaul the systems that harm our climate. The communities most exposed to climate change deserve no less.

Jessica Garcia is a senior policy analyst for climate finance at Americans for Financial Reform Education Fund.