Llewellyn King: Three out-of-step environmental groups

Rachel Carson researching with Robert Hines on the New England coast in 1952. Her book Silent Spring helped launch the environmental movement.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Greedy men and women are conspiring to wreck the environment just to enrich themselves.

It has been an unshakable left-wing belief for a long time. It has gained new vigor since The Washington Post revealed that Donald Trump has been trawling Big Oil for big money.

At a meeting at Mar-a-Lago, Trump is reported to have promised oil industry executives a free hand to drill willy-nilly across the country and up and down the coasts, and to roll back the Biden administration’s environmental policies. All this for $1 billion in contributions to his presidential campaign, according to The Post article.

Trump may believe that there is a vast constituency of energy company executives yearning to push pollution up the smokestack, to disturb the permafrost and to drain the wetlands, but he has gotten it wrong.

Someone should tell Trump that times have changed and very few American energy executives believe — as he has said he does — that global warming is a hoax.

Trump has set himself not only against a plethora of laws, but also against an ethic, an American ethic: the environmental ethic.

This ethic slowly entered the consciousness of the nation after the seminal publication of Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson, in 1962.

Over time, concern for the environment has become an 11th Commandment. The cornerstone of a vast edifice of environmental law and regulation was the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. It was promoted and signed by President Richard Nixon, hardly a wild-eyed lefty.

Some 30 years ago, Barry Worthington, the late executive director of the United States Energy Association, told me that the important thing to know about the energy-versus-environment debate was that a new generation of executives in oil companies and electric utilities were environmentalists; that the world had changed and the old arguments were losing their advocates.

“Not only are they very concerned about the environment, but they also have children who are very concerned,” Worthington told me.

Quite so then, more so now. The aberrant weather alone keeps the environment front-and-center.

This doesn’t mean that old-fashioned profit-lust has been replaced in corporate accommodation with the Green New Deal, or that the milk of human kindness is seeping from C-suites. But it does mean that the environment is an important part of corporate thinking and planning today. There is pressure both outside and within companies for that.

The days when oil companies played hardball by lavishing money on climate deniers on Capitol Hill and utilities employed consultants to find data that, they asserted, proved that coal use didn’t affect the environment are over. I was witness to the energy-versus-climate-and-environment struggle going back half a century. Things are absolutely different now.

Trump has promised to slash regulation, but industry doesn’t necessarily favor wholesale repeal of many laws. Often the very shape of the industries that Trump would seek to help has been determined by those regulations. For example, because of the fracking boom, the gas industry could reverse the flow of liquified-natural-gas at terminals, making us a net exporter not importer.

The United States is now, with or without regulation, the world’s largest oil producer. The electricity industry is well along in moving to renewables and making inroads on new storage technologies like advanced batteries. Electric utilities don’t want to be lured back to coal. Carbon capture and storage draws nearer.

Similarly, automakers are gearing up to produce more electric vehicles. They don’t want to exhume past business models. Laws and taxes favoring EVs are now assets to Detroit, building blocks to a new future.

As the climate crisis has evolved so have corporate attitudes. Yet there are those who either don’t or don’t want to believe that there has been a change of heart in energy industries. But there has.

Three organizations stand out as pushing old arguments, shibboleths from when coal was king, and oil was emperor.

These groups are:

The Sunrise Movement, a dedicated organization of young people that believes the old myths about big, bad oil and that American production is evil, drilling should stop, and the industry should be shut down. It fully embraces the Green New Deal — an impractical environmental agenda — and calls for a social utopia.

The 350 Organization is similar to the Sunrise Movement and has made much of what it sees as the environmental failures of the Biden administration — in particular, it feels that the administration has been soft on natural gas.

Finally, there is a throwback to the 1970s and 1980s: an anti-nuclear organization called Beyond Nuclear. It opposes everything to do with nuclear power even in the midst of the environmental crisis, highlighted by Sunrise Movement and the 350 Organization.

Beyond Nuclear is at war with Holtec International for its work in interim waste storage and in bringing the Palisades plant along Lake Michigan back to life. Its arguments are those of another time, hysterical and alarmist. The group doesn’t get that most old-time environmentalists are endorsing nuclear power.

As Barry Worthington told me: “We all wake up under the same sky.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Looking for solace

“A Tear for October 7” (marble on burned wood), by Newton, Mass.-based sculptor Memy Ish-Shalom, in his show “Searching for Hope in Dark Times,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, June 6-30. He’s a native of Israel.

He says:

“In the past two years, we have all experienced and lived through devastating historical events. Such events have a significant impact on me as a human being and as an artist. I found myself compelled to respond to these tragic events through my art. In this show, I reflect on the atrocities and the collective trauma my friends and family in Israel experienced on October 7.

“These are, indeed, dark times. On troubled, sleepless nights, I find myself looking up at the sky, gazing at the moon, the stars, and the clouds, or looking down at the stones and rocks on the ground, in search for some solace in their enduring beauty. On other occasions, I take a deep look at people. Whenever I encounter people with courageous and optimistic spirits, I feel inspired and more hopeful.”

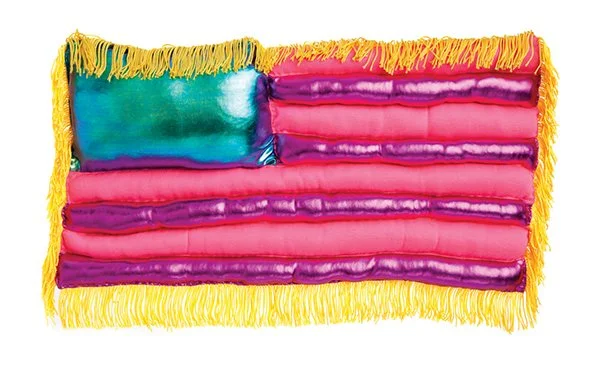

Revolutionary coverings

“Lil Glory’’ (fabric, polyester fill, fringe), by Natalie Baxter, in the show “Stiching the Revolution: Quilts as Agents of Change,’’ at the Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, Conn., opening May 19.

The show presents about 30 quilts from the museum’s collection, and loans from other New England institutions and contemporary artists. The exhibition pairs historic and modern quilts spanning over 200 years of production viewed as pivotal mediums that express potent beliefs and inspire important change.

Waterbury skyline from the west, with Union Station clock tower at left. The city was once known as the brass and clock / watch capital of America. New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, lived near Waterbury in 1962-66 and remembers the many factories still open, the toxic pollution of the Naugatuck River, which flowed through the city, and the necessity of walking up and down steep hills.

The multiplying uses of seaweed

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

When I was a kid living along Massachusetts Bay, we often saw seaweed (various species of marine macroalgae – kelp, etc.) as somewhat irritating. It could get in the way of fishing lines, and it would pile up on beaches in rank rows.

But seaweed, which, blessedly, grows rapidly, is looking better and better. It absorbs carbon dioxide, absorption that directly fights global warming, and it offsets a bit of ocean acidification caused by carbon dioxide from our fossil-fuel burning; it slows coastal erosion by weakening the force of waves in storms that have worsened as sea levels rise, and provides shelter for innumerable marine creatures. It’s used to make food, fertilizer, medicines, bioplastics, biofuel and animal feed.

(I’m sure that many readers have tried the seaweed salad in ethnic Asian restaurants.)

And now researchers are investigating its use as a source of minerals, such as platinum and rhodium, as well as “rare-earth” elements (which actually aren’t that rare), that are crucial in the renewable-energy sector and in other technological applications, too. Seaweed sucks up these minerals.

Much more research needs to be done to demonstrate all possible uses of seaweed, but the potential for seaweed aquaculture seems enormous. I can see many profitable new seaweed farms being developed off the southern New England coast. There’s already a large kelp-farming sector in the Gulf of Maine, benefiting from the size of available waters, and the industry is growing along the Rhode Island and Connecticut shoreline, too.

It’s heartening to see scientists working on all-natural ways to address global warming. Of course, in some places there will be fights over which sites to take over for seaweed farming; I hope that the broad public interest will usually win over, say, the demands of summer yachtsmen. Certainly, these farm sites should be chosen carefully, with guidance from the likes of the Marine Biological Laboratory, in the village of Woods Hole in Falmouth, Mass.

Hit these links and this one (video).

Llewellyn King: New graduates should learn how to manage rejection

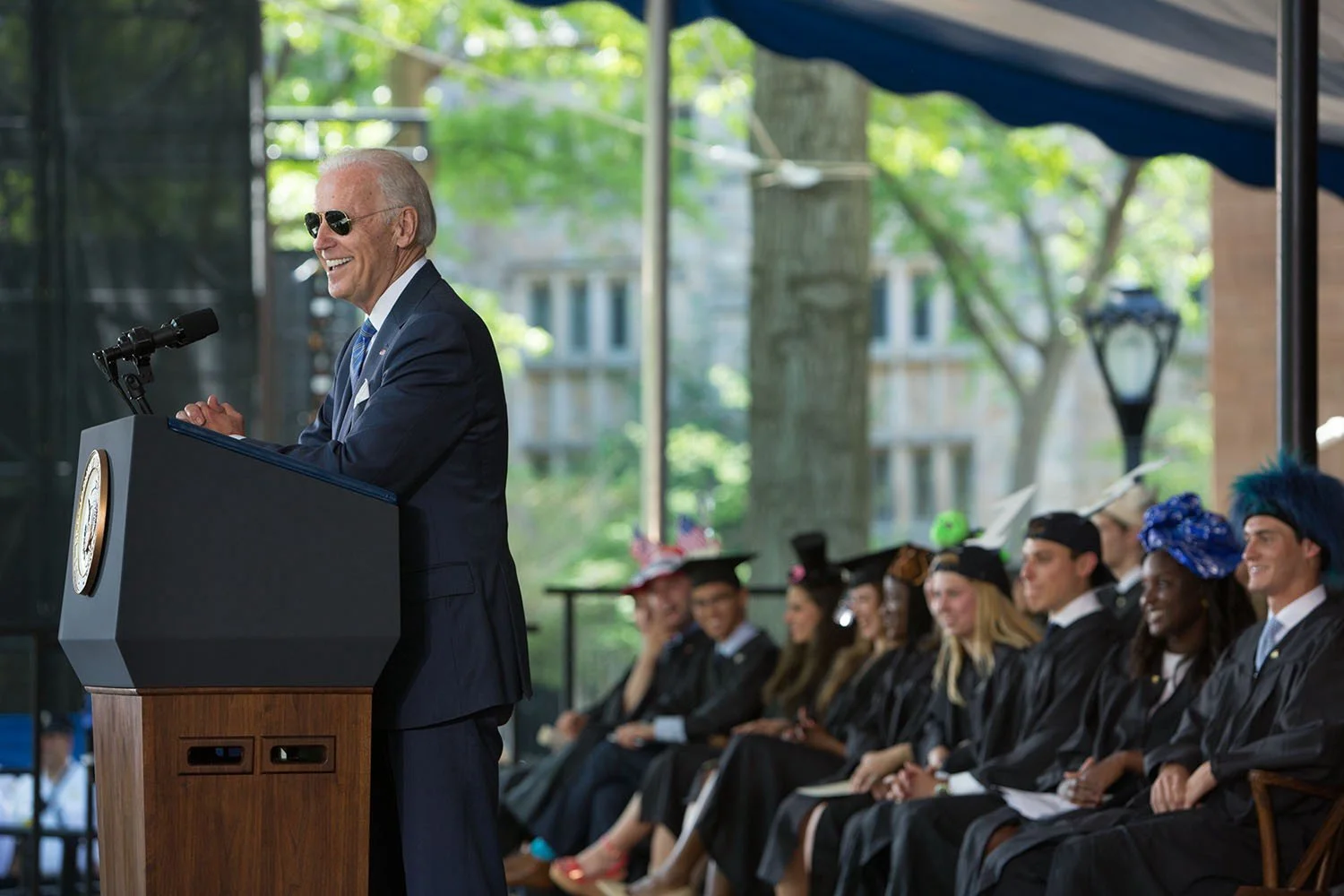

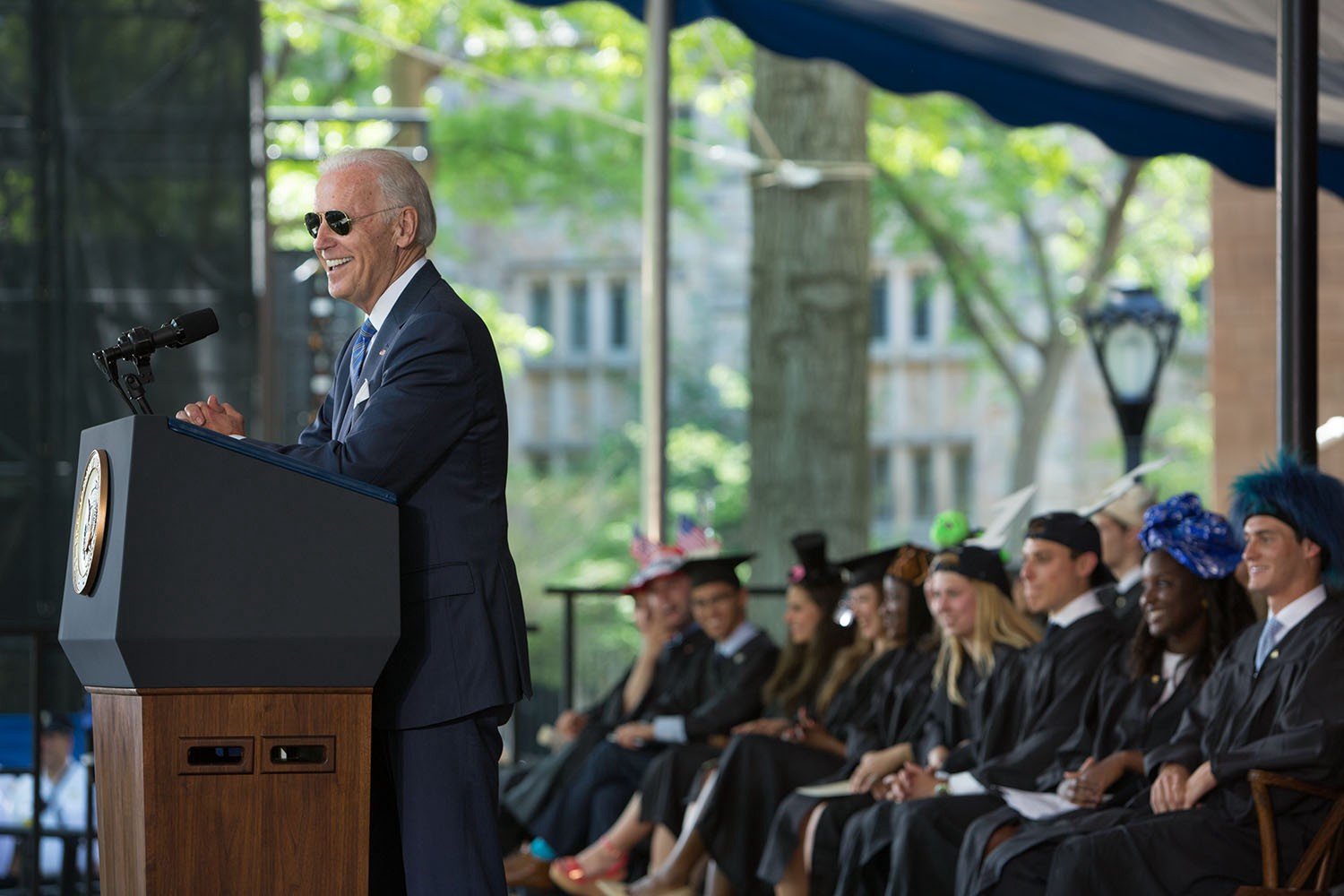

Then-Vice President Biden giving commencement speech at Yale University in 2015.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

As so many commencement addresses aren’t being delivered this year, I thought I would share what I would have said to graduates if I had been invited by a college or university to be a speaker.

“The first thing to know is that you are graduating at a propitious time in human history — for example, think of how artificial intelligence is enabling medical breakthroughs.

“A vast world of possibilities awaits you because you are lucky enough to be living in a liberal democracy. It happens to be America, but the same could be true of any of the democratic countries.

“Look at the world, and you will see that the countries with democracy are also prosperous places where individuals can follow their passion. Doubly or triply so in America.

“Despite all the disputes, unfairness and politics, the United States is foremost among places to live and work — where the future is especially tempting. I say this having lived and worked on three continents and traveled to more than 180 countries. Just think of the tens of millions who would live here if they could.

“In a society that is politically and commercially free, as it is in the United States, the limits we encounter are the limits we place on ourselves.

“That is what I want to tell you: Don’t fence yourself in.

“But do work always to keep that freedom, your freedom, especially now.

“Seldom mentioned, but the greatest perverters of careers, stunters of ambition and all-around enfeeblers you will contend with aren’t the government, a foreign power, shortages or market conditions, but how you manage rejection.

“Fear of rejection is, I believe, the great inhibitor. It shapes lives, hinders careers and is ever-present, from young love to scientific creation.

“The creative is always vulnerable to the forces of no, to rejection.

“No matter what you do, at some point you will face rejection — in love, in business, in work or in your own family.

“But if you want to break out of the pack and leave a mark, you must face rejection over and over again.

“Those in the fine and performing arts and writers know rejection; it is an expected but nonetheless painful part of the tradition of their craft. If you plan to be an artist of some sort or a writer, prepare to face the dragon of rejection and fight it all the days of your career.

“All other creative people face rejection. Architects, engineers and scientists face it frequently. Many great entrepreneurial ideas have faced early rejection and near defeat.

“If you want to do something better, differently or disruptively, you will face rejection.

“To deal with this world where so many are ready to say no, you must know who you are. Remember that: Know who you are.

“But you can’t know who you are until you have found out who you are.

“Your view of yourself may change over time, but I adjure you always to judge yourself by your bests, your zeniths. That is who you are. Make past success your default setting in assessing your worth when you go forth to slay the dragons of rejection.

“There are two classes of people you will encounter again and again in your lives. The yes people and the no people.

“Seek out and cherish those who say yes. Anyone can say no. The people who have changed the world, who have made it a better place, are the people who have said, ‘Yes.’ ‘Why not?’ ‘Let’s try.’

“Those are people you need in life, and that is what you should aim to be: a yes person. Think of it historically: Thomas Edison, Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt and Steve Jobs were all yes people, undaunted by frequent rejection.

“Try to be open to ideas, to different voices and to contrarian voices. That way, you will not only prosper in what you seek to do, but you will also become someone who, in turn, will help others succeed.

“You enter a world of great opportunities in the arts, sciences and technology but with attendant challenges. The obvious ones are climate, injustice, war and peace.

“Think of yourselves as engineers, working around those who reject you, building for others, and having a lot of fun doing it.

“Avoid being a no person. No is neither a building block for you nor for those who may look to you. Good luck!”

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island.

White House Chronicle

‘Too much my own’

A mayfly

.

“Watching those lifelong dancers of a day

As night closed in, I felt myself alone

In a life too much my own.…’’

— From “Mayflies,’’ by Richard Wilbur (1921-2017), mostly Massachusetts-based poet

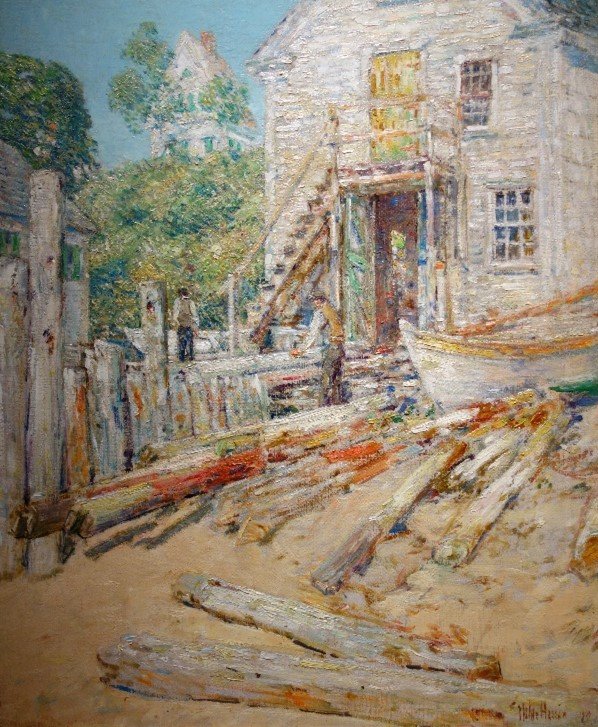

The beauty of work

“Rigger's Shop, Provincetown,’’ (oil on canvas), by Childe Hassam (1859-1902), in the show “Impressionist New England: Four Seasons of Color and Light,’’ through Oct. 20, at Heritage Museums and Gardens, Sandwich, Mass.

This is from the collection of New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. Lawrence Pond

Dictator of the social climbers

Newport picnic supervised by Ward McAllister.

"Snobbish Society's Schoolmaster” —Caricature of Ward McAllister as an ass telling Uncle Sam he must imitate "an English snob of the 19th Century" or he "will nevah be a gentleman".

Text excerpted from a New England Historical Society article by Emily Parrow

“In Gilded Age Newport, Rhode Island, an invitation to one of Ward McAllister’s summer picnics could make or break a hopeful social climber.

“One contemporary aptly described this era as ‘an ever-shifting kaleidoscope of dazzling wealth, restless endeavor, and rivalry.’ American ideas about class were changing, especially in cities. Old and new money mixed like oil and water. The increase in American fortunes necessitated stricter guidelines for social acceptance. Enter McAllister, a controversial figure who coached this evolving class of insecure millionaires in Old World aristocratic customs.’’

Troubling origin stories

“The invisible enemy should not exist – Seated Nude Male Figure, Wearing Belt Around Waist” (Middle Eastern packaging, newspapers, glue and cardboard), by Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz, in the show “Never Spoken Again: Rogue Stories of Science and Collections,’’ at the Fleming Museum of Art, at University of Vermont, Burlington, through May 18.

— Courtesy of the artist and Barbara Wien Gallery.

The museum says the show is a traveling exhibition that reflects on “the birth of modern collections, the art institutions that sustain them, and their contingent origin stories to reveal a universe of erasures, violence, and fortuity. Considering how institutional collections organize our lives, “Never Spoken Again” brings together artists whose works open up a critique of material culture, iconography and political ecologies.

“In turn, each of the works sheds light on myths, simulations, fake currencies, war games, and the slow violence of systematic racism that historically underpin collecting practices. Together, they invite inquiry into how our collective histories are presented, curated, fabricated, or all of the above. With wit, curiosity, and compassion, “Never Spoken Again” asks the question most museum visitors dare not: How did these objects and artworks get to a gallery in Vermont anyway? And why?

Burlington's Union Station was built in 1916 by the Central Vermont Railway and the Rutland Railroad.

‘Metaphor for living’

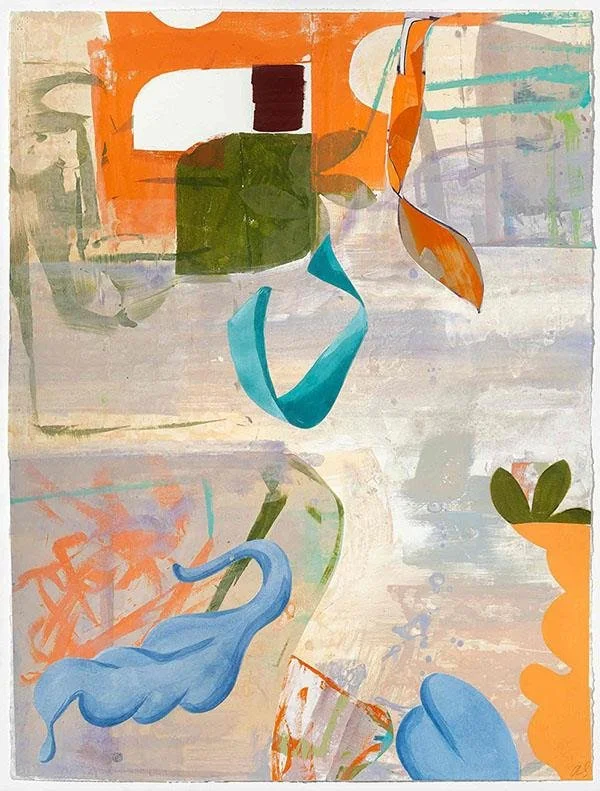

“Dropkick into Primordial Soup” (mixed media), by Cambridge, Mass.-based artist Alexandra Sheldon, in her show “Piece by Piece,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through June 2.

She says:

“Collage is a process of piecing together papers. When I began with the collages in this show, I gathered painted papers for a background. Then I would hunt for shapes to go into the backgrounds. Often the work got too busy, and then I’d try to simplify it by reintroducing backgrounds. This led to shifting surfaces and a back and forth feel which felt good to me.

“Collage is, for me, a metaphor for living. It is difficult to live: to figure out how to balance work with family with body with money with time with everything. In the studio I am searching for combinations of energies. I want to fit in movement, color, shape, line, texture, light, feel, everything. I want suspense, sorrow, enthusiasm, inertia, joy, fear, exploration, everything.

“If in real life I can hardly figure out how to live, at least in the studio I can attempt to jam in everything and explore everything. This is how I find myself: by spending long hours in the studio listening to music and trying to put papers together. Collage leads me and frustrates me, entices me and overjoys me.’’

“And in the end, perhaps it’s those fleeting moments of fun and play in the studio which I love most. Just like in my life.’’

Chris Powell: Don't leave looted Conn. hospitals' fate to a big game of chicken

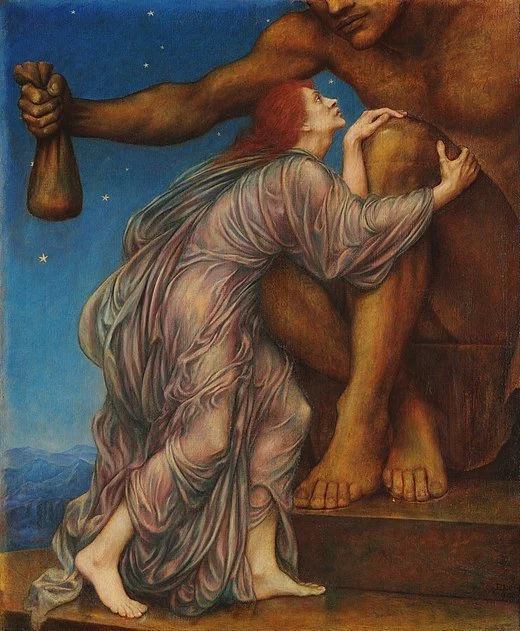

“The Worship of Mammon,’’ by Evelyn De Morgan (1909).

MANCHESTER, Conn.

A big game of chicken may determine what becomes of Waterbury (Conn.) Hospital, Manchester (Conn.) Memorial Hospital, and Rockville General Hospital, in Vernon, Conn.

Yale New Haven Health, which two years ago agreed to buy the three struggling hospitals from Prospect Medical Holdings for $435 million, now is suing Prospect to nullify the agreement. Yale New Haven Health contends that Prospect has substantially impaired the hospitals by mismanagement since the agreement was made.

Prospect's Connecticut hospitals were already in terrible financial condition, most of their equity having been stripped from them and liquidated by their parent company, Leonard Green and Partners, a private-equity investment firm based in California. The Prospect hospitals no longer own their own real estate but must pay rent to a real-estate company.

Connecticut law never should have allowed nonprofit hospitals, which Waterbury, Manchester and Rockville were, to be acquired by investment companies like Prospect. The state now has a big interest in keeping the hospitals operating, restoring their solvency, and returning them to nonprofit status.

But Yale New Haven Health has a big interest in not overpaying for an operation that may be on the verge of collapse and bankruptcy. After all, Yale New Haven Health runs four hospitals in Connecticut, all nonprofits, and they could be critically weakened if their parent company pays too much for the Prospect hospitals.

As the condition of the Prospect hospitals deteriorated after Yale New Haven Health agreed to acquire them, Yale New Haven Health asked state government to subsidize its purchase by $80 million. Gov. Ned Lamont didn't want to do that and urged the two sides to keep negotiating. But with the acquisition unfulfilled after two years and the lawsuit charging bad faith, negotiations have failed and seem unlikely to resume soon. The Prospect hospitals are far behind in paying bills and state and municipal taxes. They may not have any net worth left at all.

But the Prospect hospitals serve large communities and their closure would be a disaster for Connecticut. Other hospitals are not prepared to take up the displaced patient load, and even if they could handle it, many patients of the failing hospitals and the doctors who treat them would have far to travel. The disruption to medical care in the state would be immense. Despite Prospect's awful ownership and top management, its hospitals employ hundreds of dedicated professionals striving to provide excellent care under worsening financial stress.

State government's financial intervention in support of an acquisition by Yale New Haven Health strikes many as the obvious solution.

But a state subsidy for the purchase will ratify Prospect's looting of its three hospitals and the real-estate company's purchase of the hospitals' property. The real-estate company now may think it has decisive leverage over whoever acquires the hospitals and intends to keep them operating. But if the hospitals fail and go out of business, their buildings probably would lose much of their value, since they have practical use only as hospitals.

The best mechanism for saving the hospitals may be to let them fail and go into bankruptcy. Bankruptcy is exclusively a federal court process but with the court's approval state government could become a party to the case and assist the financial reorganization of the hospitals from the moment of their bankruptcy filing. Bankruptcy could relieve the hospitals of their burdensome property rental obligations.

In any case state government should do more than what it long has been doing about this problem -- just hoping that Yale New Haven Health and Prospect will work things out eventually before the Prospect hospitals collapse and close. Hope is not a strategy or plan.

So the governor should assemble a team ready to assist a bankruptcy proceeding, the General Assembly should make millions of dollars in an emergency loan available to a new owner of the hospitals, and the legislature and governor should give Connecticut a law to prevent nonprofit hospitals from falling into the hands of predators ever again, and thus to prevent the theft of decades of community charity that state government's negligence allowed here.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Augmented reality in Medfield

“Agent 57’’ (detail from Alpha augmented reality), by Michael Lewy, in the group show “Augmented Reality — The evolution of a small town,’’ at the Zullo Gallery Center for the Arts, Medfield, Mass., May 11-June 23.

The gallery says the show’s works focus on the past, present and future of the town of Medfield, which was once best known for its big state mental hospital.

The Boston origins of Mother’s Day

Julia Ward Howe

Text excerpted from The Boston Guardian

(Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s editor, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

Mother’s Day got its start on Beacon Street in Boston’s Back Bay celebrating not only mothers but peace.

Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910), who lived most of her life at 241 Beacon Street, began advocating a “Mother’s Day” in the 1870s.

The ancient Greeks held spring ceremonies for Rhea, mother of gods, and in the 1600s the English had a “Mothering Day”, where servants were given the fourth Sunday of Lent off to bring cakes to their mothers.

America’s Mother’s Day, however, started with Howe.

Howe was not an average mother.

She was an activist, an abolitionist, a women’s suffrage advocate and a writer who clashed with her prominent transcendentalist husband Samuel Gridley Howe over his wish that she shun public life. According to her diary, he beat her. She considered divorcing him on various occasions but never did.

1915 Mother’s Day card. Of course, some may have more nuanced views of their mothers.

Christopher Niezrecki: What has hurt the offshore wind industry, and what to do about it

The five-turbine wind farm off Block Island

LOWELL, Mass.

America’s first large-scale offshore wind farms began sending power to the Northeast in early 2024, but a wave of wind farm project cancellations and rising costs have left many people with doubts about the industry’s future in the U.S.

Several big hitters, including Ørsted, Equinor, BP and Avangrid, have canceled contracts or sought to renegotiate them in recent months. Pulling out meant the companies faced cancellation penalties ranging from US$16 million to several hundred million dollars per project. It also resulted in Siemens Energy, the world’s largest maker of offshore wind turbines, anticipating financial losses in 2024 of around $2.2 billion.

Altogether, projects that had been canceled by the end of 2023 were expected to total more than 12 gigawatts of power, representing more than half of the capacity in the project pipeline.

So, what happened, and can the U.S. offshore wind industry recover?

Estimates of the mean annual wind speeds in meters per second extending 200 kilometers from shore at a height of 330 feet (100 meters). ESMAP/The World Bank via Wikimedia, CC BY

I lead UMass Lowell’s Center for Wind Energy Science Technology and Research WindSTAR and Center for Energy Innovation and follow the industry closely. The offshore wind industry’s troubles are complicated, but it’s far from dead in the U.S., and some policy changes may help it find firmer footing.

Long approval process’s cascade of challenges

Getting offshore wind projects permitted and approved in the U.S. takes years and is fraught with uncertainty for developers, more so than in Europe or Asia.

Before a company bids on a U.S. project, the developer must plan the procurement of the entire wind farm, including making reservations to purchase components such as turbines and cables, construction equipment and ships. The bid must also be cost-competitive, so companies have a tendency to bid low and not anticipate unexpected costs, which adds to financial uncertainty and risk.

The winning U.S. bidder then purchases an expensive ocean lease, costing in the hundreds of millions of dollars. But it has no right to build a wind project yet.

Continental shelf areas leased for wind power development along the Atlantic coast. U.S. Department of the Interior, 2024

Before starting to build, the developer must conduct site assessments to determine what kind of foundations are possible and identify the scale of the project. The developer must consummate an agreement to sell the power it produces, identify a point of interconnection to the power grid, and then prepare a construction and operation plan, which is subject to further environmental review. All of that takes about five years, and it’s only the beginning.

For a project to move forward, developers may need to secure dozens of permits from local, tribal, state, regional and federal agencies. The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, which has jurisdiction over leasing and management of the seabed, must consult with agencies that have regulatory responsibilities over different aspects in the ocean, such as the armed forces, Environmental Protection Agency and National Marine Fisheries Service, as well as groups including commercial and recreational fishing, Indigenous groups, shipping, harbor managers and property owners.

For Vineyard Wind I – which began sending power from five of its 62 planned wind turbines off Martha’s Vineyard in early 2024 – the time from BOEM’s lease auction to getting its first electricity to the grid was about nine years.

Costs can balloon during the regulatory delays

Until recently, these contracts didn’t include any mechanisms to adjust for rising supply costs during the long approval time, adding to the risk for developers.

From the time today’s projects were bid to the time they were approved for construction, the world dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, global supply chain problems, increased financing costs and the war in Ukraine. Steep increases in commodity prices, including for steel and copper, as well as in construction and operating costs, made many contracts signed years earlier no longer financially viable.

New and re-bid contracts are now allowing for price adjustments after the environmental approvals have been given, which is making projects more attractive to developers in the U.S. Many of the companies that canceled projects are now rebidding.

The regulatory process is becoming more streamlined, but it still takes about six years, while other countries are building projects at a faster pace and larger scale.

Shipping rules, power connections

Another significant hurdle for offshore wind development in the U.S. involves a century-old law known as the Jones Act.

The Jones Act requires vessels carrying cargo between U.S. points to be U.S.-built, U.S.-operated and U.S.-owned. It was written to boost the shipping industry after World War I. However, there are only three offshore wind turbine installation vessels in the world that are large enough for the turbines proposed for U.S. projects, and none are compliant with the Jones Act.

That means wind turbine components must be transported by smaller barges from U.S. ports and then installed by a foreign installation vessel waiting offshore, which raises the cost and likelihood of delays.

A generator and blades head for the South Fork Wind farm from New London, Conn., on Dec. 4, 2023. AP Photo/Seth Wenig

Dominion Energy is building a new ship, the Charybdis, that will comply with the Jones Act. But a typical offshore wind farm needs over 25 different types of vessels – for crew transfers, surveying, environmental monitoring, cable-laying, heavy lifting and many other roles.

The nation also lacks a well-trained workforce for manufacturing, construction and operation of offshore wind farms.

For power to flow from offshore wind farms, the electricity grid also requires significant upgrades. The Department of Energy is working on regional transmission plans, but permitting will undoubtedly be slow.

Lawsuits, disinformation add to the challenges

Numerous lawsuits from advocacy groups that oppose offshore wind projects have further slowed development.

Wealthy homeowners have tried to stop wind farms that might appear in their ocean view. Astroturfing groups that claim to be advocates of the environment, but are actually supported by fossil fuel industry interests, have launched disinformation campaigns.

In 2023, many Republican politicians and conservative groups immediately cast blame for whale deaths off the coast of New York and New Jersey on the offshore wind developers, but the evidence points instead to increased ship traffic collisions and entanglements with fishing gear.

Such disinformation can reduce public support and slow projects’ progress.

Efforts to keep the offshore wind industry going

The Biden administration set a goal to install 30 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2030, but recent estimates indicate that the actual number will be closer to half that.

Passengers on a boat view America’s first offshore wind farm, owned by the Danish company Ørsted. Its five turbines generate power off Block Island, R.I. AP Photo/David Goldman

Despite the challenges, developers have reason to move ahead.

The Inflation Reduction Act provides incentives, including federal tax credits for the development of clean energy projects and for developers that build port facilities in locations that previously relied on fossil fuel industries. Most coastal state governments are also facilitating projects by allowing for a price readjustment after environmental approvals have been given. They view offshore wind as an opportunity for economic growth.

These financial benefits can make building an offshore wind industry more attractive to companies that need market stability and a pipeline of projects to help lower costs – projects that can create jobs and boost economic growth and a cleaner environment.

Christopher Niezrecki is director of the Center for Energy Innovation at the Center for Energy Innovation at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell.

Mr. Niezrecki is director of UMass Lowell’s Industry-University Cooperative Research Center for Wind Energy Science Technology and Research (WindSTAR), which receives funding from the National Science Foundation and several energy-related companies.

Five years wide awake

"Once in everyone's life there is apt to be a period when he is fully awake, instead of half asleep. I think of those five years in Maine as the time when this happened to me ... I was suddenly seeing, feeling, and listening as a child sees, feels, and listens. It was one of those rare interludes that can never be repeated, a time of enchantment. I am fortunate indeed to have had the chance to get some of it down on paper."

From One Man’s Meat, E.B. White’s collection of essays written for Harper’s Magazine, in a foreword written 40 years after its initial publication, in 1942. He moved to a “salt-water farm’’ in Brooklin, Maine, in 1938 from New York City (where he frequently returned to work at The New Yorker in stints). The farm most famously inspired the classic children’s (and adults’) book Charlotte’s Web.

Using 3D printing in building neighborhoods

Home built using University of Maine 3D printer and wood.

Edited from a New England Council report

“The University of Maine has created a 3D printer that could be used to build a house, cutting construction times and costs. Now, it is one of the largest in the world and could be capable of being used to build entire neighborhoods. The recently publicized printer is four times the size of the original one, commissioned less than five years ago, and can use bio-based materials (such as wood from Maine’s big forestry sector) to address affordable-housing issues as well.

“This new massive printer ‘opens up new research frontiers to integrate these collaborative robotics operations at a very large scale with new sensors, high-performance computing, and artificial intelligence,’ said Habib Dagher, director of the university’s Advanced Structures & Composite Center, at the university’s flagship campus, in Orono, where UMaine houses its printers.

Get out the insulin

“Ice Cream Sandwich”, by Connecicut artist Peter Anton, at the Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum, May 10-July 27.

The gallery says:

“Anton's work, made of wood, metal, plastic resin, oil and acrylic paints, encourages "people to think about their own relationship to food, and the memories and nostalgia that these childhood favorites conjure."

Llewellyn King: The trials of celebrity love, from Taylor-Burton to Swift-Kelce

Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra (1963)

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I wouldn’t know Taylor Swift if she sat next to me on an airplane, which is unlikely because she travels by private jet. If she were to take a commercial flight, she wouldn’t be sitting in the economy seats, which the airlines politely call coach.

Swift (who lives in Watch Hill, R.I., part of the time) needs to go by private jet these days: She is dating Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce, and that is a problem. Love needs candle-lightin,g not floodlighting.

Being in love when you are famous, especially if both the lovers are famous, is tough. The normal, simple joys of that happy state are a problem: There is no privacy, precious few places outside of gated homes where the lovers can be themselves.

They can’t do any of the things unfamous lovers take for granted, like catching a movie, holding hands or stealing a kiss in public without it being caught on video and transmitted on social media to billions of fans. Dinner for two in a cozy restaurant and what each orders is flashed around the world. “Oysters for you, sir?”

Worse, if the lovers are caught in public not doing any of those things and, say, staring into the middle distance looking glum, the same social media will erupt with speculation about the end of the affair.

If you are a single celebrity, you are gossip-bait, catnip for the paparazzi. If a couple, the speculation is whether it will be wedding bells or splitsville.

The world at large is convinced that celebrity lovers are somehow in a different place from the rest of us. It isn’t true, of course, but there we are: We think their highs are higher and lows are lower.

That is doubtful, but it is why we yearn to hear about the ups and downs of their romances; Swift’s more than most because they are the raw material of her lyrics. Break up with Swift and wait for the album.

When I was a young reporter in London in the 1960s, I did my share of celebrity chasing. Mostly, I found, the hunters were encouraged by their prey. But not when Cupid was afoot. Celebrity is narcotic except when the addiction is inconvenient because of a significant other.

In those days, the most famous woman in the world, and seen as the most beautiful, was Elizabeth Taylor. I was employed by a London newspaper to follow her and her lover, Richard Burton, around London. They were engaged in what was then, and maybe still is, the most famous love affair in the world.

The great beauty and the great Shakespearian actor were the stuff of legends. It also was a scandal because when they met in Rome, on the set of Cleopatra, they were both married to other people. She to the singer Eddie Fisher and he to his first wife, the Welsh actress and theater director Sybil Williams.

Social rules were tighter then and scandal had a real impact. This scandal, like most scandals of a sexual nature, raised consternation along with prurient curiosity.

My role at The Daily Sketch was to stake out the lovers where they were staying at the luxury Dorchester Hotel, on Park Lane.

I never saw Taylor and Burton. Day after day I would be sidetracked by the hotel’s public-relations officer with champagne and tidbits of gossip, while they escaped by a back entrance.

Then, one Sunday in East Dulwich, a leafy part of South London where I lived with my first wife, Doreen, one of the great London newspaper writers, I happened upon them.

Every Sunday, we went to the local pub for lunch, which included traditional English roast beef or lamb. It was a good pub — which today might be called a gastropub, but back then it was just a pub with a dining room. An enticing place.

One Sunday, we went as usual to the pub and were seated right next to my targets: the most famous lovers in the world, Taylor and Burton. The elusive lovers, the scandalous stars were there next to me: a gift to a celebrity reporter.

I had never seen before, nor in the many years since, two people so in love, so aglow, so entranced with each other, so oblivious to the rest of the room. No movie that they were to star in ever captured love as palpable as the aura that enwrapped Taylor and Burton. You could warm your hands on it. Doreen whispered from behind her hand, “Are you going to call the office?”

I looked at the lovers and shook my head. They were so happy, so beautiful, so in love I didn’t have the heart to break the spell.

I wasn’t sorry I didn’t call in a story then and I haven’t changed my mind.

Love in a gilded cage is tough. If Swift and Kelce are at the next table — unlikely -- in a restaurant, I will keep mum. Love conquers all.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Web site: whchronicle.co

‘Dreamscapes’

‘Reader” (oil on linen), by Anthony Cudahy, in his show ‘‘Spinneret,’’ at the Ogunquit (Maine) Museum of American Art,

— Photograph by JSP Art Photography

Eric J. Taubert writes of the show:

"Step inside the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, and a luminous transformation unfolds. The salt-spray roar of the Gulf of Maine retreats and a different type of sensory gale rises up. Phosphorescent dreamscapes. Intoxicating light and shadows. Hues so delicious you can almost taste them. Familiar faces you couldn’t possibly know. This is 'Spinneret,' the first solo exhibition in the United States by the contemporary figurative painter Anthony Cudahy.’’

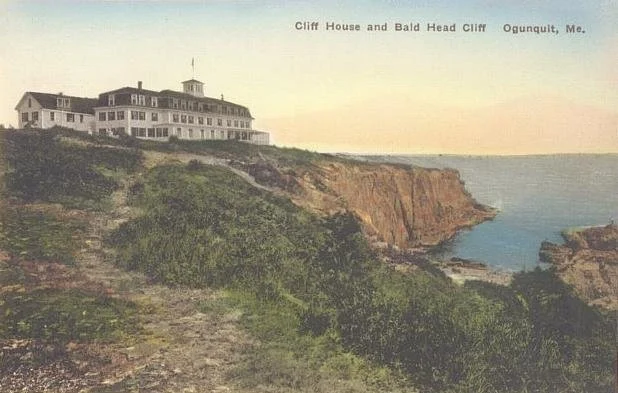

The Cliff House in Ogunquit in 1920

‘Mass timber’ building

Mixed coniferous and deciduous forest in Presque Isle, Maine.

—Photo by Itsasatire

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Most of New England is woodland, especially, of course, Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. Well-managed forests can be an economic boon, especially given the renewability of wood as a building material. (Let’s hope that a hurricane doesn’t blow down a lot of it, which is what happened in 1938.)

I thought of this after reading Abigail Brone’s article on the New England News Collaborative website about the use of “mass timber,’’ which involves installing wood panels in place of concrete and steel, whose manufacturing emits a great deal of carbon dioxide. The wood panels are shipped to building sites from fabrication centers elsewhere. Installing wood cuts labor costs compared to handling concrete and steel. This, among other things, could encourage a speedup in much-needed housing construction over the next few years.

Ms. Brone notes that the cost of mass timber in New England is substantially raised by having to be shipped from the South and Canada. But why not harvest a lot of New England wood for the purpose – especially from Maine, which is almost 90 percent forested?

A University of Maine report says:

“The Maine Mass Timber Commercialization Center (MMTCC) brings together industrial partners, trade organizations, construction firms, architects, and other stakeholders in the region to revitalize and diversify Maine’s forest-based economy by bringing innovative mass timber manufacturing to the State of Maine. The emergence of this new innovation-based industry cluster will result in positive economic impacts to both local and regional economies, particularly in Maine’s rural communities.”