David Warsh: The split records of Keynes and Friedman

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

From the beginning I have been convinced that Milton Friedman possessed a dual personality, somewhat like Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde: a strong economist by day, a weak citizen by night. Nothing I’ve read and written about in the last nine weeks has convinced me otherwise, not even Edward Nelson’s meticulous explication ofFriedman’s professional life from 1929 to 1972.

Instead, my suspicions have grown with the passage of time that with John Maynard Keynes, it was the other way around. What if Keynes was a weak technical economist, but a strong citizen by night? Turning things on their heads after seventy-five years requires time, a critical biography by a first-rate economist in the future, and, in my case, not much more than cheek. I’ll sketch the bare bones of the argument here, and hope to return to it someday.

This puts me up against the judgment of Nelson and, worse, of Friedman himself. In Newsweek magazine, in 1970, he wrote:

“Now John Maynard Keynes was one of the greatest economists of all time. I know many people who regard him as a devil who brought all sorts of evil things into this world – he was not that; he was like rest of us; he made mistakes. He was a great man, so when he made mistakes, they were great mistakes. But he was a great man.”

But I am a journalist, not an economist, and it’s the mistakes that interest me, one of them in particular: his diagnosis of the causes of the Great Depression. Keynes regarded it as, like any recession, a drop in aggregate demand, moving economic output below the production capacity of the economy. In such circumstances, he argued, governments should counter recessions through an expansionary fiscal policy that boosts aggregate demand.

Friedman and his research partner Anna Schwartz advanced a different explanation of the Great Depression in their A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960. Ben Bernanke, a leading scholar of the decade of the 1930s, before he became a central banker, summarized their argument this way: “central bankers’ outmoded doctrines and flawed understanding of the economy had played a crucial role in that catastrophic decade, demonstrating the power of ideas to shape events.”

In 2007-08. Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke, with the help of many others, forcefully demonstrated the power of better ideas. Together, they saved the world from a Second Great Depression.

Keynes may have had many brilliant ideas as an economist, but his single greatest success came as a journalist. The Economic Consequences of the Peace, his 1919 book, fiercely criticized the harsh reparations demanded of Germany in the wake of World War I, correctly foresaw the causes of World War II, and supplied the foundations of the 1947 Marshall Plan, aimed at the reconstruction of Germany, not punishment for its many sins.

My friend, Peter Renz like me, a non-economist, described the essence of Keynes this way: “a romantic figure. A polymath, brilliant as a writer, alive with charm as a lover, witty, political, a man of business and action.”

In this view, Keynes, born in 1883, was the last eminent Victorian of a certain sort. He was not included in that volume of portraits written by Keynes’s friend Lytton Strachey. Perhaps he, along with Friedman, will appear in a volume by some latter-day Strachey. (The figment of my imagination is the tenth good book). Meanwhile, I can’t do better than Wikipedia’s summary of the original:

“Eminent Victorians is a book by Lytton Strachey (one of the older members of the Bloomsbury Group), first published in 1918, and consisting of biographies of four leading figures from the Victorian era. Its fame rests on the irreverence and wit Strachey brought to bear on three men and a woman who had, until then, been regarded as heroes: Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold and Gen. Charles Gordon. While Nightingale is actually praised and her reputation enhanced, the book shows its other subjects in a less-than-flattering light, for instance, the intrigues of Cardinal Manning against Cardinal Newman.”

And Friedman? He had two great successes as an economist. One of them should be clear by now. That single chapter of the Monetary History makes engrossing reading. It has its flaws – the significance it assigns to the 1930 failure of the grandly named Bank of the United States, a hastily assembled commercial bank in New York City, chartered in 1913, seems overblown – but overall, Friedman’s and Schwartz’s analytic narrative of the series of banking panics that unfolded 1930-33 is convincing.

Friedman’s other achievement is more diffuse but more important. He brought monetary analysis back into the big tent of economics that that had been dominated for more than a century by analysis of “real” goods and services by the forces of supply and demand. I keep on the shelf above my desk two little Cambridge Handbooks of 1922, Supply and Demand, by H. D. Henderson, and Money, by D. H. Robertson.

That was the situation before Keynes. In his General Theory, he sought to unite them, but the makers of macroeconomics who followed him somehow have failed to come up with an account of a business cycle without periodic financial crises.

“Monetarism,” a slogan that Friedman is said to have disliked, as opposed to “monetary theory,” doesn’t do much better, but at least it puts central banks back in the the story. As for rules as an alternative to occasional discretion, as a means of deflecting the occasional crisis? I doubt it.

And Friedman’s dark side? Nothing worse than being the most prominent spokesman for an exaggerated version of the common failing of today’s economics – its emphasis on the role of the individual, at the expense of attention to his/her/their entanglement in society (in Herbert Gintis’s phrase). British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher famously proclaimed “There’s no such thing as society.” That’s bunk, even worse than macro without crises.

At least the tale of Jekyll and Hyde is the story one journalist has to tell.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Tentative early ‘spring’

— Photo by Greg Hume

“Two yellow dandelion shields do not make spring,

nor do the wild duck swimming by the shore,

so self-possessed, so white of side and breast,

nor, I suppose, the change in land-birds’ calls….’’

From “Night Wind in Spring,’’ by Elizabeth Coatsworth (1893-1986), Maine poet

Chimney Farm, in Nobleboro, Maine, where Elizabeth Coatsworth lived with her husband, the famed writer Henry Beston.

‘The ongoing tension’

“Pangolin” (steel, paper, and credit cards), by Christy Rupp, in her show “Streaming: Sculpture by Christy Rupp,’’ at the Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum, through April 27.

— Courtesy of the artist

The museum says:

“Understood as one of the early pioneers in the field of ecological art activism, the artist, activist and thought-leader Christy Rupp has an international reputation. Streaming {features} a survey of Rupp’s intricate collages, wall installations and free-standing sculpture, which chronicle the ongoing tension between natural systems and the environment in transition, and call our attention to our interconnectedness with non-humans and habitat – transmuting detritus gathered from the waste stream through collage and sculpture to reveal what is hidden away from common view and understanding. Informed by science and the historical representation of natural history, the artwork in this exhibition examines the way we frame our opinions of nature, using irony and wit to represent the human impact on our natural habitat.’’

Mind-reading to smooth relations

Colorized phot of Saran Orne Jewett’s house in South Berwick, Maine, taken in 1910.

Lookout Point, in Harpswell Maine.

— Photo by Kyle MacLea

“We were standing where there was a fine view of the harbor and its long stretches of shore all covered by the great army of the pointed firs, darkly cloaked and standing as if they waited to embark. As we looked far seaward among the outer islands, the trees seemed to march seaward still, going steadily over the heights and down to the water's edge.”

xxx

“Tact is after all a kind of mind-reading.’’

— Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909) in her novel Country of the Pointed Firs, like much of her work set on the southern coast of Maine

Tea time

“Wondergrrrl Teapot’’ (cast terracotta, underglazes, glazes), by Sarah Peters, in her show with Don Nakamura, titled “Bold Women and Vivid Dreams,’’ at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass., through June 2.

— Image courtesy of Cahoon Museum of American Art

Chris Powell: A heavy discounting of outrageous crime in Conn.; teachers aren’t underpaid

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Next time the governor and state legislators boast about the decline in Connecticut's prison population, remember the recent report in the Hearst Connecticut newspapers about the state Board of Pardons and Paroles.

By a vote of 2-1 after a hearing in January, the board approved parole for a Bridgeport man who had served only 26 years of a 60-year sentence for an especially outrageous crime in 1995. He kidnapped a 16-year-old girl from her home in Pennsylvania and took her to Bridgeport, where he imprisoned her for weeks, molesting her, stabbing her, burning her with a cigarette, and mutilating her, carving his name into her chest with broken glass.

Of course the perpetrator already had an extensive criminal record. For years after his conviction he denied the crime and brought fruitless appeals. He accepted responsibility only when seeking parole.

Prosecutors opposed his application but the board granted it in large part because he had participated in various programs in prison. His victim said she did not oppose parole but is still recovering from her ordeal and just wanted it to be over.

Connecticut should want such hefty discounting of criminal justice to be over. But it won't be over any time soon.

While there is no constituency at the state Capitol for improving the ever-declining performance of students in Connecticut's public schools, there is a huge constituency for spending more money in the name of education even as student enrollment declines. That constituency is so large that no one at the Capitol dares to talk back to it even as it spouts nonsense.

More nonsense came the other day from Kate Dias, president of the state's largest teacher union, the Connecticut Education Association. "The critical thing to remember," Dias told education money seekers at the Capitol, "is we've never fully funded education."

But exactly what is "fully funded"? Dias didn't say, but "fully funded" seems to mean whatever the teacher unions want.

If education was "fully funded," Dias added, "my teachers wouldn't have a starting salary of $48,000. ... We've never actually done the really hard things that we need to do that would allow our teachers, our pre-K, everyone to make reasonable middle-class wages in Connecticut."

Teachers in Connecticut aren't middle class? According to the CEA's national affiliate, the National Education Association, the average teacher salary in Connecticut is $81,000, which doesn't count excellent benefits and much time off during the summer.

And if Dias is sore about an average starting salary of $48,000, that may be the fault of teacher unions themselves for negotiating contracts that allocate most increases in school spending to people who are already employed and union members. Why raise salaries for people who aren't paying union dues yet?

Where is the elected official or political candidate who dares to ask how increases in education spending correlate with student performance, or how student performance correlates with anything beyond family income and parenting? Any such elected official or candidate soon would find scores of teachers in his district vigorously supporting his opponent's campaign.

Indeed, that seems about to happen to state Sen. Douglas McCrory, D-Windsor, an administrator with the Capitol Region Education Council, who -- remarkably, since he is a Democrat -- may be the General Assembly's most vocal advocate of charter schools and school choice.

McCrory is being challenged for renomination by a school board member in his home town and by an official of a union that represents school employees in Hartford.

More than improving education, McCrory's opponents may want to make sure that schools don't ever have to compete for students -- that school choice is limited to families who can afford private schools.

Special interests are political machines that are very good at getting their people to vote. The public interest has no political machine.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Mary Burke: The luck of the Irish has often evaded the Kennedy family

The Kennedy family on the beach in Hyannisport in 1931.

From article in The Conversation by Mary Burke

John F. Kennedy, whose ancestors left Ireland during the potato famine of the mid-19th century, was famously the first United States president of Catholic Irish descent.

When Americans narrowly elected Kennedy in 1960, anti-Catholic bias was still part of the mainstream culture.

I am a scholar of Irish literature and the author of “Race, Politics, and Irish America: A Gothic History,” a new book that describes how the Irish were long excluded in America.

So when Kennedy accepted shamrocks from the Irish ambassador to the U.S. on his first St. Patrick’s Day in the White House in 1961, it signaled the social and political arrival of the Irish American elite. It also was a pivotal moment, marking Irish Americans’ fulfilled dream of full assimilation into the U.S.

The dream soured when Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in November 1963. That tragedy – and the many others that followed for the Kennedy family – began to be told by others in the Gothic story tradition, which hinges on nightmarish scenarios and the abuse of power.

Stick to intramural?

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

So the Dartmouth College basketball team has voted to unionize by joining the Service Employees International Union, setting off a loud explosion in the cartel called the National Collegiate Athletic Association. The team’s theory is that playing on such teams helps promote the college’s PR, and thus finances, and so they should be paid as employees, even though Dartmouth, in Hanover, N.H., provides among the most generous financial aid of any such institution in America, and academics, not athletics, is primary at such “elite” colleges unlike, it seems, at many schools.

I wonder if forcing even fairly small private colleges, such as Dartmouth, to treat athletes as employees will lead some institutions to stop competing in some inter-collegiate sports, including basketball. That sport has never been very big at Dartmouth, by the way. So maybe the college will consign it to merely intramural competition. A reasonable decision.

‘Old toilers, soil makers’

“For a hundred and fifty years, in the pasture of dead horses,

roots of pine trees pushed through the pale curves of your ribs,

yellow blossoms flourished above you in autumn, and in winter

frost heaved your bones in the ground – old toilers, soil makers….’’

— From “Names of Horses,’’ by Donald Hall (1928-2018), Wilmot, N.H.-based poet and essayist

To read the whole poem, please hit this link.

1910 image

‘Visual life to my emotions’

“Hanging By a Thread” (acrylic paint and graphite on wood panel), by Royalton, Vt.-based artist Amy Schachter, in her show “Hiding in Plain Sight,’’ at Studio Place Arts, Barre, Vt., through April 20.

— Image courtesy of Studio Place Arts

She says:

“I aim to break down the figure into a series of interlocking shapes and lines in order to guide the viewer to use their imagination to complete the image and see what's not really there. For me, art is a conversation between line, form and color. I continually strive for balance, harmony and simplicity in my work.

“My work explores the human experience as told through a female lens. The imagery in my work typically depict women, open, exposed and vulnerable yet possessing an inner strength and fortitude as illustrated by the strong framework within each piece. A stance that takes on a personal significance for me. The thought-provoking imagery highlights a personal journey that explores powerful and opposing emotions and concepts such as resilience and fragility, perseverance and surrender, reality and fantasy. The creative process involved while expressing myself through art has given visual life to my emotions. It has provided me with a quiet language and a way to safely explore some of the darker corners of my mind. It allows me to take control of some of the messier things in life and approach them in a more positive way. The strength and wit expressed in my work provides a reminder that beauty can exist within chaos, as does light within darkness’’.

Royalton in the fall.

Llewellyn King: The little, and now thriving, island nation that pulls on our heartstrings

A wave of runners in the Holyoke, Mass., St. Patrick's Day Road Race pass the starting line.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Ready for craic on Sunday?

Craic, pronounced crack, is an Irish word that has seeped into English and means party or revelry.

Try as you may, you won’t avoid Sunday’s craic because on Sunday, it being March 17, untold hundreds of millions of people around the world will be wearing the green. In short, celebrating St. Patrick’s Day, the national day of the Irish, by putting on something green and taking a drink.

No other nation, let alone a small nation with a troubled history, can have such a claim on the heartstrings of the planet. For one day, we are all Irish — and many of us will go to a place where drink is sold to celebrate it. There isn’t a lot of preamble to St. Paddy’s Day – except for the arrival in the pubs of green-colored beer. Ugh!

The Irish diaspora, which reached its apogee during the Potato Famine of the mid-19th Century, sent the Irish to the far corners of the earth, especially to America, where they endured for some time in poverty but eventually prospered.

They brought with them their music, which influenced American Roots Music, like Bluegrass, Folk and Country, their towering literary talent, which gave us generations of writers.

And they got into politics, big time.

A documentary now in production and scheduled to be released in 12 episodes at the end of the year, From Ireland to the White House, traces the Irish ancestry of 24 U.S. presidents from Andrew Jackson (of Scots-Irish lineage) to Joe Biden.

Tony Culley-Foster, the U.S. representative of Tamber Media, the Dublin company producing the series, tells me the scholarship has been exacting in tracing the ancestry of the presidents. He said the 24 presidents on the list have been certified by the same independent historians and genealogists used by Clinton and Biden.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there are 31.5 million Americans who claim Irish heritage. So it has become important for presidents to make pilgrimages to Ireland — to wrap themselves in green.

From my experience in Ireland, the two taken mostly to heart as being of their own, were John Kennedy and Ronald Reagan and of those, Kennedy was the greater heartthrob for the Irish.

My late friend Grant Stockdale’s father was Kennedy’s ambassador to Ireland, and Grant spent his mid-teen years in Dublin at the U.S. Embassy in Phoenix Park. “I knew what it must be like to be royalty,” Grant told me.

But it isn’t just the presidency that has been shaped by Irish heritage. Irish names are to be found on every public service list, from the U.S. Congress to the local school board. There have been great senators, like Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D.-N.Y.) and great speakers of the House, such as the towering, Boston-Irish Tip O’Neill (D.). If it’s politics, it’s Irish.

In Britain, too, historically some of the greatest statesmen and orators in the House of Commons have been Irish, think Edmund Burke and Charles Parnell.

For me, Ireland’s gift to the world has been its contribution to English literature. Hundreds of great names come to mind. Try Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, Samuel Beckett and Edna O’Brien.

And the books keep coming, tumbling out of the most literary fertile minds on earth.

Two contemporary writers dominate my thinking: John Banville and Sally Rooney. Banville is prolific, profound and a joy to read, a master craftsman at the top of his form. Rooney is a kind of literary Taylor Swift, writing about the sex, love and isolation of young adults of her generation. I am keen to see how she evolves and if she will give joy for generations, as great writers do.

Literacy is part of the fabric of Irish life. An Irish person, far from literary circles, will ask you conversationally, “What is your book?” Translation: “What are you reading?” Ireland treasures books and reading is a national pastime.

Ireland’s literacy may have saved its economy. At a bleak period when, just 40 years ago, I heard many Irish leaders talk about “structural unemployment” of 22 percent, American scientific publishers found that highly literate women were a resource. That led to a boom in footnoting in Ireland, followed by American Express looking for accurate inputting and, suddenly, Ireland was transformed from one of the poorest countries of Europe to a boom nation and the Silicon Valley of Europe, as the computer giants moved in. A town known for its bookstores and fishing, Galway, became ground zero for computing in Ireland.

Craic has no discernible economic value except for the brewers and distillers, but it is such fun. As the Irish say, slainte (cheers)!

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

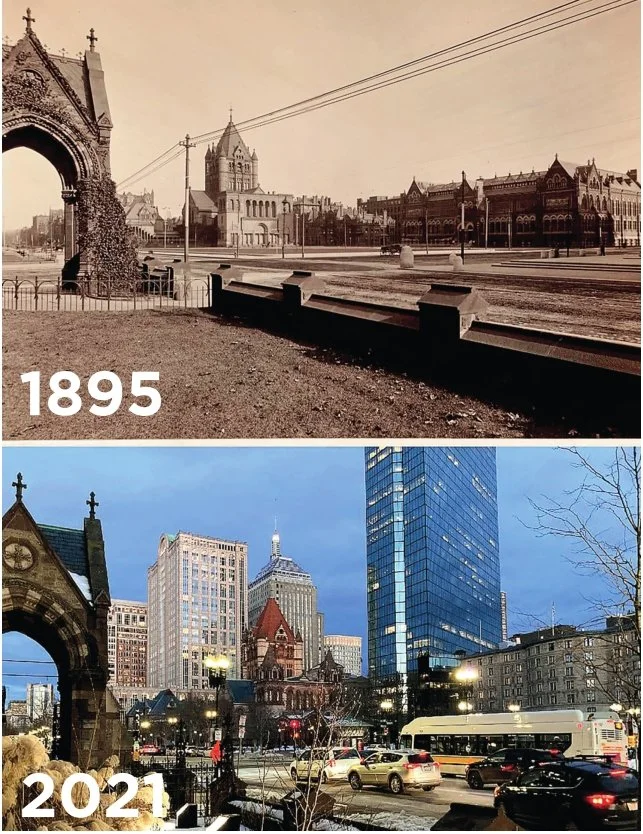

Trying to meld historic preservation, diversity and climate resilience in Boston

Edited from a Boston Guardian article

(Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s editor/publisher, is The Boston Guardian’s chairman.)

“The administration of Boston Mayor Michelle Wu wants to expand the city’s preservation policies to focus on diversity and climate resilience.

“The enhancements were explained at a citywide meeting by Murray Miller, director of the Office of Historic Preservation (OHP), a city entity established by Wu in 2022.

“The OHP comprises three bodies.

“Drawing most of the office’s resources, the Landmarks Commission works to protect Boston’s historic structures. It also oversees the ten local historic district commissions, each of which focuses on preserving a different Boston neighborhood. The office also includes the Commemoration Commission and the Archaeology Program.

“For much of the meeting, Miller presented the office’s strategic vision. Overall, he said he intends to expand the office’s purview beyond its traditional role as a regulator of landmarks.

“One of the office’s key focuses, he said, will be to tell the ‘full story’ of the city’s history. The office will devote more money to discovering and preserving historic sites connected to Boston’s Black, indigenous, immigrant and LGBTQ communities..

“Miller also highlighted climate resilience as an important mission for the office.

“Incentivizing developers to renovate existing structures could help increase resilience, he said, as could reworking Article 85, a part of Boston’s zoning code that allows applicants to request a demolition delay for potentially historic buildings.’’

To read the full article, please hit this link.

David Warsh: Thanks to them, we avoided a second Great Depression

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960 (National Bureau of Economic Research,1962), by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, is a most intimidating book. A heavy-lifting 860 pages, packed full of tables and charts, some of them old-fashioned fold-outs. It introduces itself as an “analytical narrative” of changes of the stock of money in the U.S. over slightly less than a century.

It begins with a quotation from the great 19th Century economist Alfred Marshall, a sly swipe at the short equation-filled “papers” that, since the 30’s, had become standard:

“Experience in controversies such as these brings out the impossibility of learning anything from the facts till they are examined and interpreted by reason; and teaches that the most reckless and treacherous of all theorists is he who professes to let the facts and figures speak for themselves, who keeps in the background the part he has played, perhaps unconsciously, in selecting them and grouping them, and in suggesting the argument post hoc ergo propter hoc’’ {after this, therefore because of this.”]

One day in the late ‘70’’s, MIT graduate student Ben Bernanke went to see his adviser, Prof. Stanley Fischer. Bernanke had finished his field examinations; he was seeking a topic for a dissertation. At one point, Fischer handed him a copy of A Monetary History and said, “Read this. It may bore you to death. But if it excites you, you might consider doing monetary economics.”

The book fascinated him, Bernanke wrote in 21st Century Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve from the Great Inflation to Covid -19 (Norton, 2022). “It got me interested not only in monetary economics, but also in the causes of the Great Depression of the 1930s, a topic I would return to frequently in my academic ‘writings.” Friedman and Schwartz had showed, he wrote, “that central bankers’ outmoded doctrines and flawed understanding of the economy had played a crucial role in that catastrophic decade, demonstrating the power of ideas to shape events.”

In 1983, Bernanke published ‘‘Non-monetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the great Depression,” a comparative study – an analytic narrative of the macroeconomics of the Great Depression, “macroeconomics” being the research field that had been brought into existence by the event itself.

About the same time, Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig set out to describe, in a series of mathematical models, the purposes that banks serve in economies of all sorts, and then explored their mathematical model of the purposes that banks serve in economies and the circumstances that sometimes lead to their collapses via bank runs.

Thirty-nine years later, the three men were recognized with Nobel Memorial Prizes for their early work on central banking, the interplay of central banks, commercial banks, and “shadow” banks that had been at the heart of the global financial crisis of 2007-08 and the lengthy recession that followed.

A footnote in the Nobel Committee’s Scientific Background to the awards notes:

“Keynes (1936) argued that recessions were primarily due to drops in aggregate demand, moving economic output below the production capacity of the economy. According to this view, governments should counter recessions through an expansionary fiscal policy that boosts aggregate demand.”

In his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes gives short shrift to central banking.

Between times, Bernanke, in particular, had led an interesting life. For a decade he taught at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business, conducting further research on banking, financial markets, labor markets, and business cycles, before moving to Princeton University, in 1995.

In 2002, he was appointed to the seven-member Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board, and 2005, became chairman of President George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers. A year later Bush nominated him to chair the Federal Reserve Board.

The president later joked that he had chosen Bernanke from among several other suitable candidates because he would sometimes come to White House briefings wearing white socks with his business attire. A more satisfying explanation was supplied by Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip, who later wrote that, beginning with the time he chaired Princeton’s economics department, Bernanke had developed a “knack for eliciting cooperation from those with bigger egos and sharper elbows.” An MIT professor recalled, “Until 2002, we hadn’t even known that he was a Republican.”

Also in 2002, as an expert on the Great Depression, Bernanke offered to a star-studded birthday party for Milton Friedman a short but incisive review of the reception of A Monetary History by the economics profession. He concluded, speaking directly to Friedman and Schwartz, “You were right, Milton, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.”

In 2006, as Fed chairman, Bernanke began organizing behind the scenes the complicated web of emergency measures that ultimately enabled the Fed, in concert with the central banks of 10 other first-rank nations, to avoid turning a banking panic into a second Great Depression, as bad, perhaps even worse, than the first.

Not everyone agrees – see, for example, Paul Krugman – but if the Nobel Committee in 1976 had enjoyed the gift of perfect foresight, they might have stressed the contribution of A Monetary History more forcefully than they did in awarding Friedman the prize, and they might have offered a medal to Schwartz as well.

It could have gone better. As governor of Israel’s central bank, Stan Fischer, in different circumstances, avoided the mortgage collapse almost entirely – but the results of the Panic of 2008 in New York could have been worse – much, much worse – had Friedman and Schwartz not spent 12 years writing their old-fashioned 860-page book. A readable edition of the key chapter of the book The Great Contraction, about 1929-33, appeared 2008, with a new preface by Schwartz, and a new introduction by Peter Bernstein.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

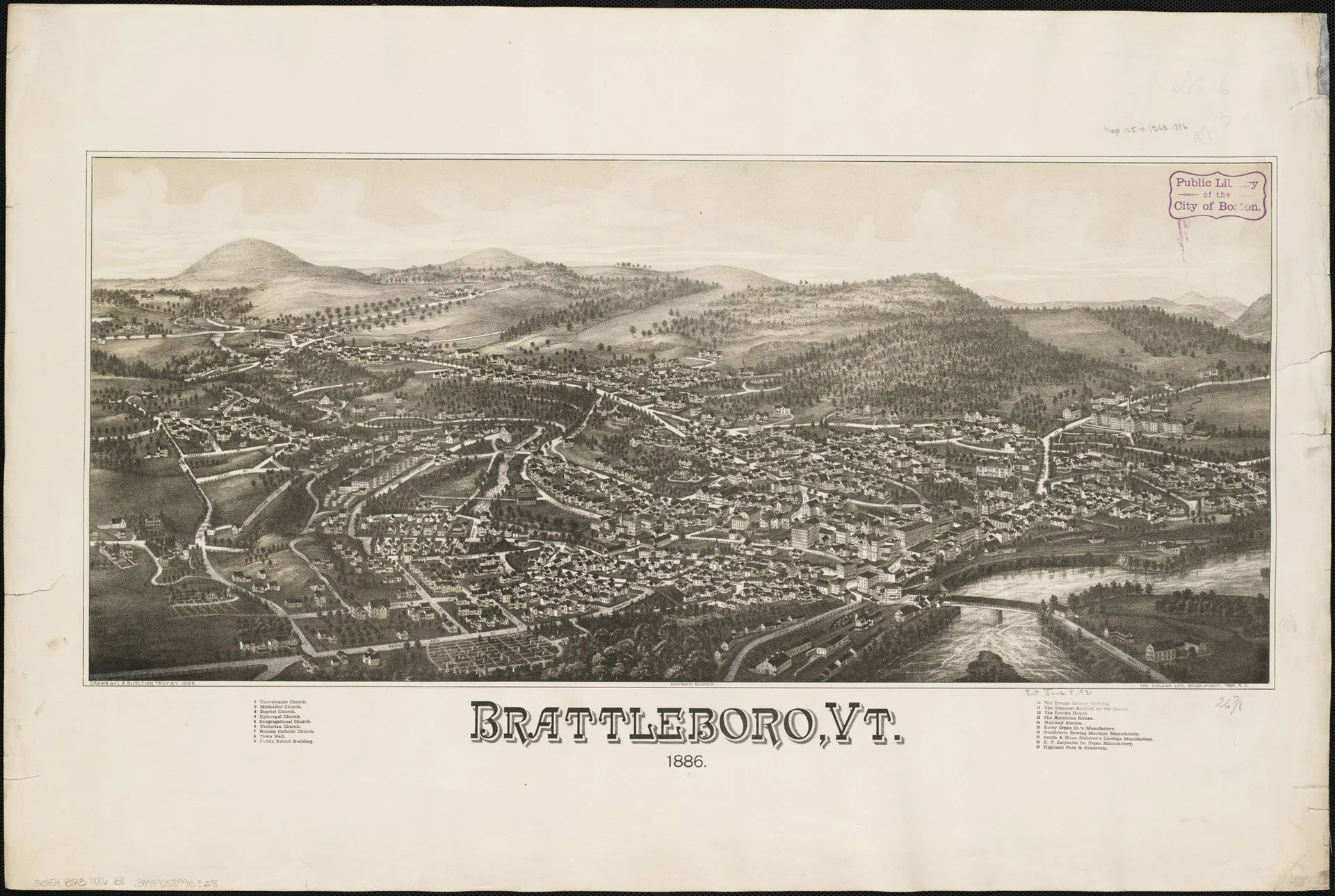

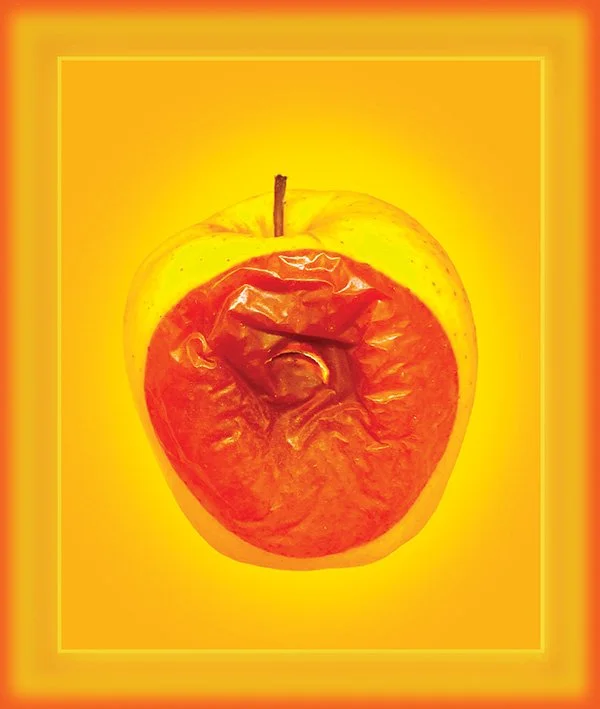

‘The idea of the Sublime’

“American Beauty 22,’’ by Lily Prince, in the group show “In Nature’s Grasp,’’ at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum and Art Center, March 16-June 16.

The museum says:

“In his 1757 work A Philosophical Enquiry, the statesman and philosopher Edmund Burke considered the concept of the Sublime, noting that certain experiences supply a kind of thrill, mixing fear and delight. Burke declared the Sublime to be the strongest human passion, powerful enough to transform the self. He noted in particular the experiences and sensations elicited by nature. Burke’s thinking challenged the rhetoric that centered human experience in religion. The idea of the Sublime became closely associated with the Romantic art movement of the 19th Century.

“Nature has long existed as the subject of artists’ interpretation. The 11 artists featured in ‘In Nature’s Grasp’’ approach nature both literally and abstractly, inviting viewers to step into their unique interpretations. Some of the artists work with landscape imagery, while others conjure ideas of nature through textures, shapes, and color, or through an aspect of their process.’’

A place for safe ‘ruthless examination’

“Universities should be safe havens where ruthless examination of realities will not be distorted by the aim to please or inhibited by the risk of displeasure.’’

— Kingman Brewster (1919-1988), president of Yale University, 1963-1977) and U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom, 1977-1981. He was thought to have inspired Garry Trudeau's fictional character President King in the comic strip Doonesbury.

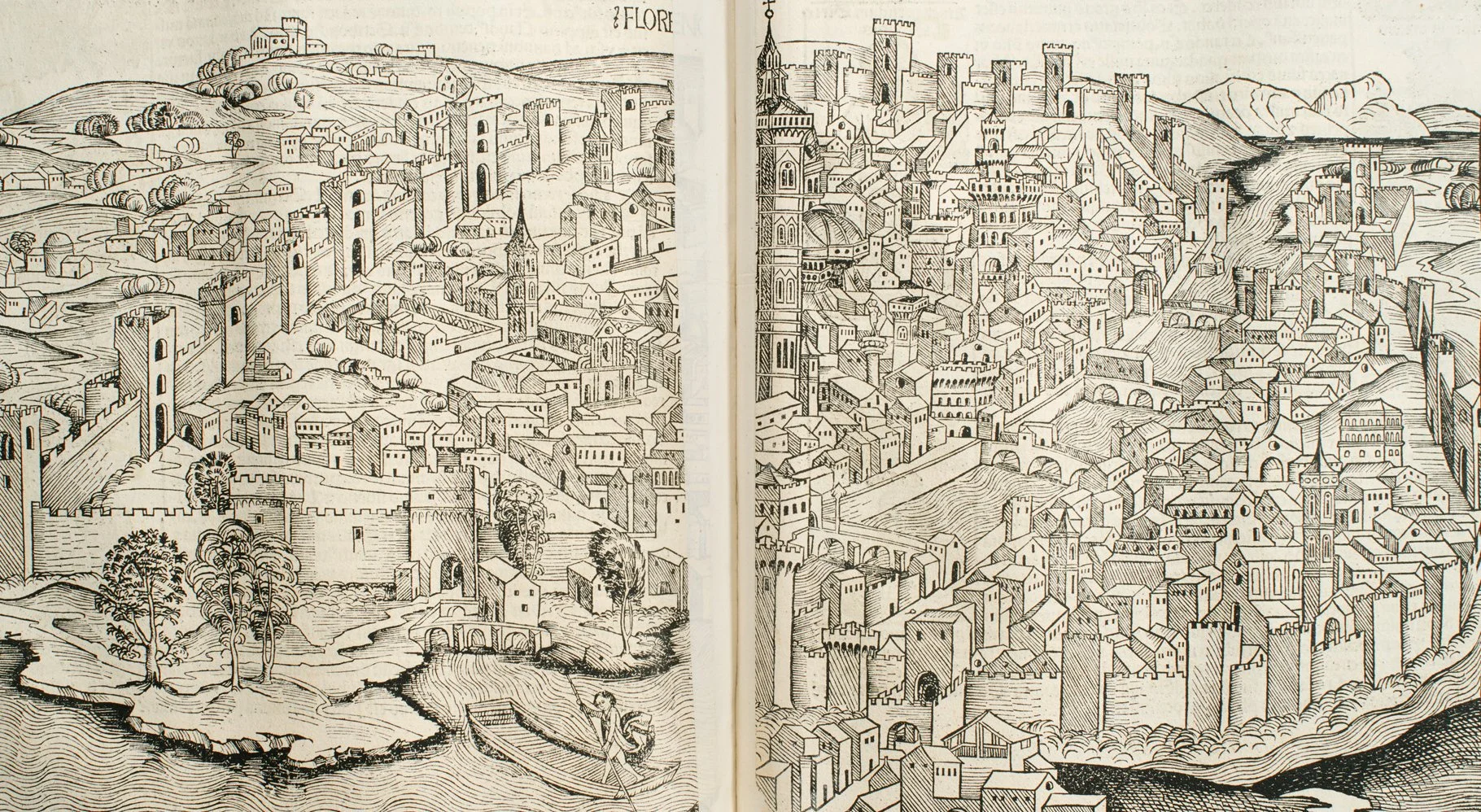

Putting cities on paper

“View of Florence from Liber chronicarum (Nuremberg Chronicle)’’, by Hartmann Schedel (German, 1440-1514)), in the “Paper Cities” show at the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass., through June 23. The Clark Is an astonishingly big museum for a place as small as Williamstown. It was built there, among other reasons, because of the hope that it would be far away from a nuclear bomb explosion in World War III.

The museum explains:

“In the sixteenth century, a vast consumer market emerged (largely in Europe) for images of cities, spurred by developments in print technology and new global exploration. Inquisitive consumers and armchair travelers were able to engage with distant places through travel books and world chronicles that offered information akin to traveling the world firsthand. Artists frequently copied maps, which often circulated widely as single-sheet prints, providing viewers with highly detailed visual information about places both near and far.

“As public fascination with cities continued to grow, so did the interest of artists in depicting them. Comprising prints and photographs spanning almost five centuries, this exhibition examines representations of a variety of U.S. and Western European cities to explore differing artists’ approaches. Some artists endeavored to offer objective records of a city’s defining monuments and topography. Others also attempted to capture a city’s character by including details such as figures or sites that represent larger socio-cultural ideas. Often, artists’ own relationships with the places they depicted influenced how they presented them to viewers. ‘‘

‘Despise the glare of wealth’

Surely you never will tamely suffer this country to be a den of thieves. Remember, my friends, from whom you sprang. Let not a meanness of spirit, unknown to those whom you boast of as your fathers, excite a thought to the dishonor of your mothers I conjure you, by all that is dear, by all that is honorable, by all that is sacred, not only that ye pray, but that ye act; that, if necessary, ye fight, and even die, for the prosperity of our Jerusalem. Break in sunder, with noble disdain, the bonds with which the Philistines have bound you. Suffer not yourselves to be betrayed, by the soft arts of luxury and effeminacy, into the pit digged for your destruction. Despise the glare of wealth. That people who pay greater respect to a wealthy villain than to an honest, upright man in poverty, almost deserve to be enslaved; they plainly show that wealth, however it may be acquired, is, in their esteem, to be preferred to virtue.’’

—- John Hancock ( 1737 -1793), an American Founding Father, rich Boston-based merchant, statesman and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. This quote is from his “Boston Massacre Oration,’’ on March 5, 1774.

On way to humus

“Celebrity (mock orange)’’ (digital print), by Hanlyn Davies, in the “Spring Heat’’ group show, at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art, New Haven, N.H., April 14-June 2.

The gallery says that the show has works that touch upon many aspects of the environment and climate change, including works by, besides Davies, those by Sariah Park, Yvonne Short, Rebecca West, Thinking about Water, Water Women, Nua Collective and more.

Huge UMass med school research building to open in June

Edited from a New England Council report

“The University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, in Worcester, will finish its new $350 million research facility (above) in June. The 350,000-square-foot center is nine stories high and include a new research space for over 70 principal investigators.

“Multiple departments and programs of the medical school are slated to be relocated to the building, including the Program in Molecular Medicine, the Horae Gene Therapy Center, the Departments of Neurology and Neurobiology, and the school’s new Program in Human Genetics & Evolutionary Biology. The facility is designed to be LEED Gold certified by the U.S. Green Building Council, making the building sustainable and energy efficient.

“‘There is a lot of site work to be done on the quad and around the building,’ said Brian Duffy, senior director of facilities management for capital projects at UMass Chan. ‘The plan is to have the area restored with beautiful green grass by Commencement.”’

Native American culture areas

From the Annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, circa 1895.