Michelle Andrews: Fertility treatment can be out of reach for the poor

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“This is really sort of standing out as a sore thumb in a nation that would like to claim that it cares for the less fortunate and it seeks to do anything it can for them.’’

— Eli Adashi, a professor of medical science at Brown University and former president of the Society for Reproductive Endocrinologists.

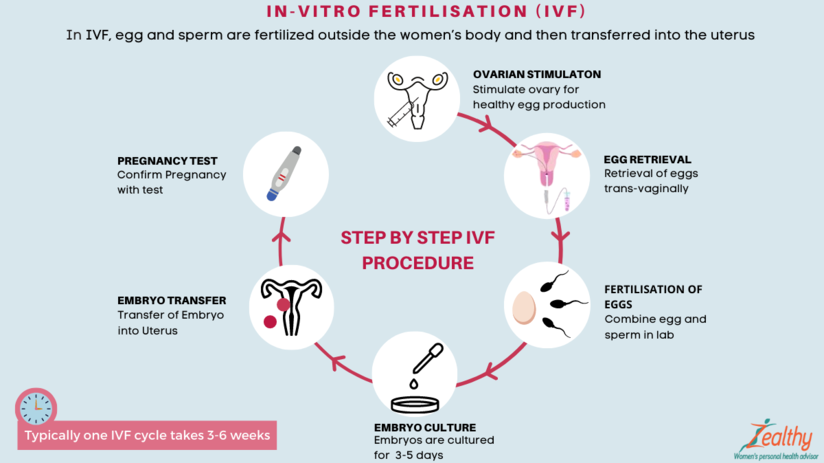

Mary Delgado’s first pregnancy went according to plan, but when she tried to get pregnant again seven years later, nothing happened. After 10 months, Delgado, now 34, and her partner, Joaquin Rodriguez, went to see an OB-GYN. Tests showed she had endometriosis, which was interfering with conception. Delgado’s only option, the doctor said, was in vitro fertilization.

“When she told me that, she broke me inside,” Delgado said, “because I knew it was so expensive.”

Delgado, who lives in New York City, is enrolled in Medicaid, the federal-state health program for low-income and disabled people. The roughly $20,000 price tag for a round of IVF would be a financial stretch for lots of people, but for someone on Medicaid — for which the maximum annual income for a two-person household in New York is just over $26,000 — the treatment can be unattainable.

Expansions of work-based insurance plans to cover fertility treatments, including free egg freezing and unlimited IVF cycles, are often touted by large companies as a boon for their employees. But people with lower incomes, often minorities, are more likely to be covered by Medicaid or skimpier commercial plans with no such coverage. That raises the question of whether medical assistance to create a family is only for the well-to-do or people with generous benefit packages.

“In American health care, they don’t want the poor people to reproduce,” Delgado said. She was caring full-time for their son, who was born with a rare genetic disorder that required several surgeries before he was 5. Her partner, who works for a company that maintains the city’s yellow cabs, has an individual plan through the state insurance marketplace, but it does not include fertility coverage.

Years after she had her first child, Joaquin , Mary Delgado found out that she had endometriosis and that IVF was her only option to get pregnant again. The news from her doctor “broke me inside,” Delgado says, “because I knew it was so expensive.” Delgado, who is on Medicaid, traveled more than 300 miles round trip for lower-cost IVF, and she and her partner, Joaquin Rodriguez, used savings they’d set aside for a home. Their daughter, Emiliana, is now almost a year old.

Some medical experts whose patients have faced these issues say they can understand why people in Delgado’s situation think the system is stacked against them.

“It feels a little like that,” said Elizabeth Ginsburg, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Harvard Medical School who is president-elect of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, a research and advocacy group.

Whether or not it’s intended, many say the inequity reflects poorly on the U.S.

“This is really sort of standing out as a sore thumb in a nation that would like to claim that it cares for the less fortunate and it seeks to do anything it can for them,” said Eli Adashi, a professor of medical science at Brown University and former president of the Society for Reproductive Endocrinologists.

Yet efforts to add coverage for fertility care to Medicaid face a lot of pushback, Ginsburg said.

Over the years, Barbara Collura, president and CEO of the advocacy group Resolve: The National Infertility Association, has heard many explanations for why it doesn’t make sense to cover fertility treatment for Medicaid recipients. Legislators have asked, “If they can’t pay for fertility treatment, do they have any idea how much it costs to raise a child?” she said.

“So right there, as a country we’re making judgments about who gets to have children,” Collura said.

The legacy of the eugenics movement of the early 20th century, when states passed laws that permitted poor, nonwhite, and disabled people to be sterilized against their will, lingers as well.

“As a reproductive justice person, I believe it’s a human right to have a child, and it’s a larger ethical issue to provide support,” said Regina Davis Moss, president and CEO of In Our Own Voice: National Black Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda, an advocacy group.

But such coverage decisions — especially when the health care safety net is involved — sometimes require difficult choices, because resources are limited.

Even if state Medicaid programs wanted to cover fertility treatment, for instance, they would have to weigh the benefit against investing in other types of care, including maternity care, said Kate McEvoy, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. “There is a recognition about the primacy and urgency of maternity care,” she said.

Medicaid pays for about 40 percent of births in the United States. And since 2022, 46 states and the District of Columbia have elected to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months, up from 60 days.

Fertility problems are relatively common, affecting roughly 10% of women and men of childbearing age, according to the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Traditionally, a couple is considered infertile if they’ve been trying to get pregnant unsuccessfully for 12 months. Last year, the ASRM broadened the definition of infertility to incorporate would-be parents beyond heterosexual couples, including people who can’t get pregnant for medical, sexual, or other reasons, as well as those who need medical interventions such as donor eggs or sperm to get pregnant.

The World Health Organization defined infertility as a disease of the reproductive system characterized by failing to get pregnant after a year of unprotected intercourse. It terms the high cost of fertility treatment a major equity issue and has called for better policies and public financing to improve access.

No matter how the condition is defined, private health plans often decline to cover fertility treatments because they don’t consider them “medically necessary.” Twenty states and Washington, D.C., have laws requiring health plans to provide some fertility coverage, but those laws vary greatly and apply only to companies whose plans are regulated by the state.

In recent years, many companies have begun offering fertility treatment in a bid to recruit and retain top-notch talent. In 2023, 45 percent of companies with 500 or more workers covered IVF and/or drug therapy, according to the benefits consultant Mercer.

But that doesn’t help people on Medicaid. Only two states’ Medicaid programs provide any fertility treatment: New York covers some oral ovulation-enhancing medications, and Illinois covers costs for fertility preservation, to freeze the eggs or sperm of people who need medical treatment that will likely make them infertile, such as for cancer. Several other states also are considering adding fertility preservation services.

In Delgado’s case, Medicaid covered the tests to diagnose her endometriosis, but nothing more. She was searching the internet for fertility treatment options when she came upon a clinic group called CNY Fertility that seemed significantly less expensive than other clinics, and also offered in-house financing. Based in Syracuse, New York, the company has a handful of clinics in upstate New York cities and four other U.S. locations.

Though Delgado and her partner had to travel more than 300 miles round trip to Albany for the procedures, the savings made it worthwhile. They were able do an entire IVF cycle, including medications, egg retrieval, genetic testing, and transferring the egg to her uterus, for $14,000. To pay for it, they took $7,000 of the cash they’d been saving to buy a home and financed the other half through the fertility clinic.

She got pregnant on the first try, and their daughter, Emiliana, is now almost a year old.

Delgado doesn’t resent people with more resources or better insurance coverage, but she wishes the system were more equitable.

“I have a medical problem,” she said. “It’s not like I did IVF because I wanted to choose the gender.”

One reason CNY is less expensive than other clinics is simply that the privately owned company chooses to charge less, said William Kiltz, its vice president of marketing and business development. Since the company’s beginning in 1997, it has become a large practice with a large volume of IVF cycles, which helps keep prices low.

At this point, more than half its clients come from out of state, and many earn significantly less than a typical patient at another clinic. Twenty percent earn less than $50,000, and “we treat a good number who are on Medicaid,” Kiltz said.

Now that their son, Joaquin, is settled in a good school, Delgado has started working for an agency that provides home health services. After putting in 30 hours a week for 90 days, she’ll be eligible for health insurance.

Michelle Andrews: is a Kaiser Family Health News contributing writer.

andrews.khn@gmail.com, @mandrews110

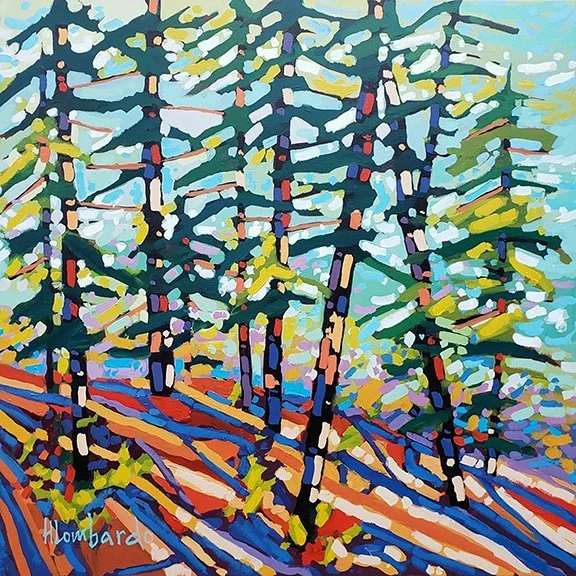

And light for us, too

“The Light Is for Me’’ (acrylic on canvas), by Holly Lombardo, at Bayview Gallery, Brunswick, Maine.

In Brunswick, the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, where, between 1850 and 1852, she wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Chris Powell: Conn. uses electricity to hide cost of government

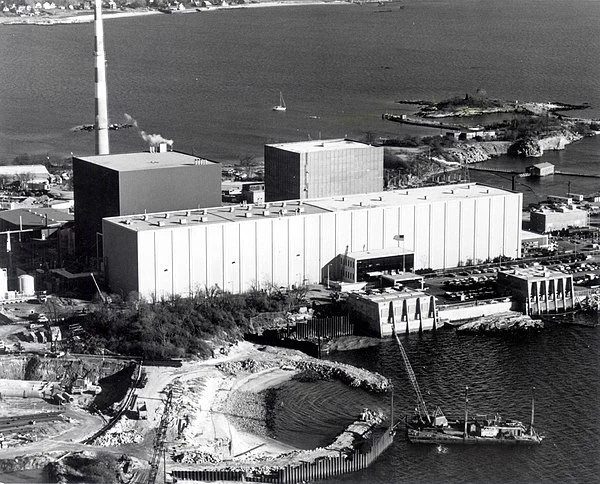

Millstone nuclear-power plant, in Waterford, Conn. State officials see the plant as vital to the state’s energy security.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Feeling unusually put-upon by state government, Connecticut's two major electric utility companies, Eversource and United Illuminating, are pushing back, which is good, since, whatever their faults, they are too easily demagogued against, as nearly everybody hates electric companies, electricity being too expensive.

Connecticut has the fourth-highest electricity costs in the country. But now the utilities, which formerly only grumbled privately about the biggest reason, are talking openly about it: government policy.

Ranking of state electricity costs.\

The forthcoming rate increases, expected to be around 19 percent, are reported to be entirely the result of two state government mandates.

The first mandate requires the utilities to purchase the production of the Millstone nuclear-power plant, in Waterford, electricity that sometimes is cheaper than other sources and sometimes isn't. State government has concluded that keeping Millstone operating is vital to Connecticut's energy security.

The second mandate requires the utilities to keep providing electricity to customers who consider themselves too poor to pay for it, whereupon that cost is transferred to customers who don't consider themselves too poor to pay and whose rates go up.

Quite apart from those mandates, Eversource long has estimated that 15-20 percent of its charges to customers arise from state mandates having little or nothing to do with the cost of the production or delivery of electricity.

Then there is the failure of Connecticut to import more natural gas, largely the result of New York's obstruction of new pipelines from the west

The co-chairman of the General Assembly's Energy and Technology Committee, Sen. Norm Needleman, D-Essex, accuses Eversource of trying to make customers pay for a cash-flow problem the company suffered as a result of its recent "wind-power investment gamble." But even there state government has to share responsibility. After all, why would electric companies "gamble" on wind power if government wasn't encouraging "green" energy and setting targets for accomplishing it?

The state government policies affecting electric rates are not necessarily wrong. But recovering their costs by hiding them in electricity bills, as Connecticut does, is dishonest. It deliberately misleads the public into thinking that the utilities are responsible for high rates when they are the work of government.

There is no social justice in requiring electricity users who pay their bills to pay as well for users who don't pay. The cost of people who don't pay their electric bills easily could be drawn against everyone from general taxation. Even the much bigger cost of subsidizing Millstone could be paid directly from general tax revenue.

Of course other taxes might have to be raised, but then people would see that it wasn't the big, bad utilities that took their money but that their own state legislators and governor did. Then people would be prompted to make a judgment on the policies behind the extra costs.

But hiding the cost of government in the cost of living is practically a principle of government in Connecticut. State taxes and the cost of state government policies are concealed not just in electricity rates but also in wholesale fuel taxes and medical and insurance bills so that energy companies, hospitals, doctors, and insurers take the blame, just as electric companies do.

Indeed, hiding the cost of government in the cost of living is now a primary principle of the federal government as well, with trillions of dollars in government expense being covered not by taxes but by borrowing, debt, the resulting money creation, and thus by inflation, which most people imagine is a force of nature, like the weather, something beyond human control.

Inflationary finance prevents people from asking their members of Congress inconvenient questions, such as how much more war in Ukraine, other stupid imperial wars, illegal immigration, Social Security, Medicare and new subsidy programs can we afford?

With their new candor about the origin of high electricity prices the utility companies are taking a big risk. Through the Public Utilities Control Authority, the governor and legislators can punish the companies expensively for telling the truth. But state government's deception of the public is already expensive.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Take a bright walk

Sunrise from the top of Cadillac Mountain, on Mt. Desert Island, Maine.

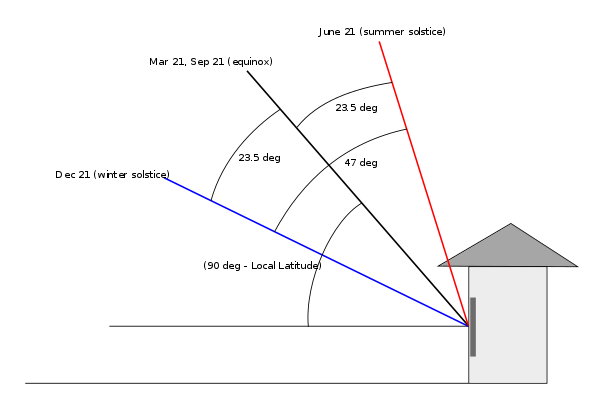

Seasonal differences in the Sun's declination, as viewed from New York City.

“Early Spring in New England” (1897), by Dwight William Tryon

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s good news for all who suffer from seasonal affective disorder. Solar spring began Feb. 5 and runs through May 4. It’s when daylight increases at the fastest pace during the year, gaining four hours and four minutes. This will gradually wake up plants, with such flowers as snowdrops blooming on south-facing slopes among the first you’ll see reacting. And wild animals will start getting more active, including that old recreation mating.

So no matter how dark world affairs may seem, there’s some hope to be found by walking around outside.

'Inhabitant of the Mind'

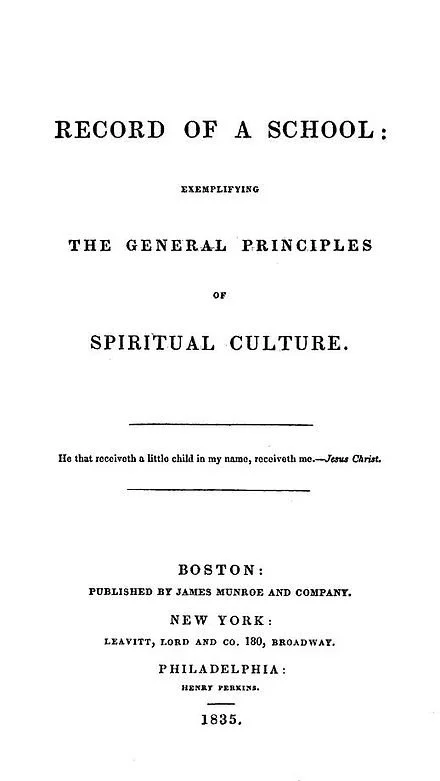

Amos Bronson Alcott created the reformist Temple School in Boston.

“I perceive that I am neither a planter of the backwoods, pioneer, nor settler there, but an inhabitant of the Mind, and given to friendship and ideas. The ancient society, the Old England of New England, Massachusetts for me.”

— Amos Bronson Alcott (1799-1888), teacher, writer and reformer and a member of the Transcendentalists group based in Concord, Mass., where he is buried in the famous Sleepy Hollow Cemetery with other intellectual luminaries of the time.

Llewellyn King: Political class is hiding between two old men; blame the primary system

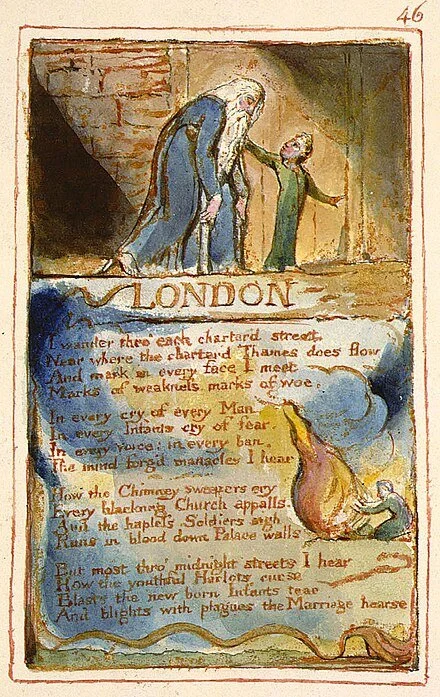

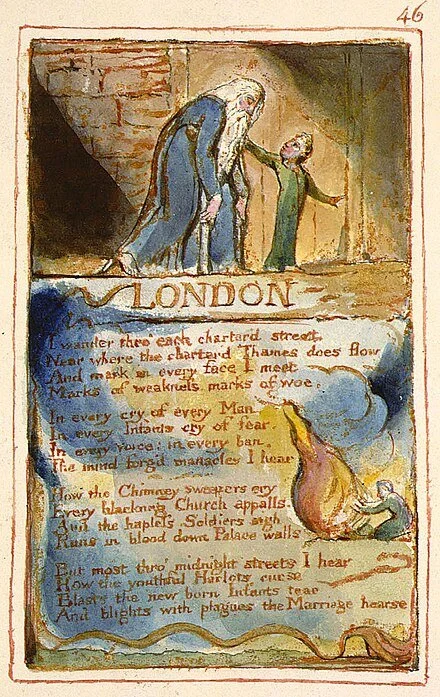

An image of an elderly man being guided by a young child accompanies William Blake's poem “London,’’ from his Songs of Innocence and Experience.

The Balsams Grand Resort Hotel, in Dixville Notch, N. H., the site of the first "midnight vote" in the New Hampshire primary.

— Photo by P199

WEST WARWICK, R.I.,

Even political junkies are feeling short of adrenaline. Two old men are stumbling toward November, spewing gaffes, garbled messages and misinformation as the political class cowers behind banners they don’t have the courage not to carry.

If you aren’t committed to Joe Biden or Donald Trump in a very fundamental way, it is a kind of torture — like being trapped in the bleachers during a long tennis match. The ball goes back and forth over the net, your head turns right, your head turns left. You watch CNN, turn to Fox, turn to MSNBC, turn back to CNN. You read The Washington Post, try The New York Times and then pick up The Wall Street Journal.

Over all hangs the terrible knowledge that this will end in a player winning who many think is unfit.

These two codgers are batting old ideas back and forth across the news. We know them too well. There is no magic here; nothing good is expected of either victory. Less bad is the goal, a hollow victory at best.

This is a replay. We can’t take comfort in the idea that the office will make the man. Rather, we feel this time, in either case, the office will unmake the man.

Both are too old to be expected to adequately deliver in the toughest job in the world. Much of the attention about age has focused on Biden, who recently turned 81, but Trump will be 78 in June and doesn’t appear to be in good health, and he delivers incomprehensible messages on social media and in public speeches.

We know what we would get from a Biden administration: more of the same but more liberal. His administration will lean toward the issues he has fought for — climate, abortion, equality, continuity.

From Trump, we know what we would get: upheaval, international dealignment, authoritarian inclinations at home, and a new era of chaotic America First. The courts will get more conservative judges, and political enemies will be punished. Trump has made it clear that vengeance is on his to-do list.

One candidate or the other, we are facing agendas that say “back to the future.”

But that isn’t the world that is unfolding. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the late, great Democratic senator from New York, said “the world is a dangerous place.”

Doubly so now, when engulfing war is a possibility, when there is an acute housing crisis at home, and when the next presidency will have to deal with the huge changes that will be brought about by artificial intelligence. These will be across the board, from education to defense, from automobiles to medicine, from the electric power supply to the upending of the arts.

How have we come to such a pass when two old men dodder to the finish line? The fact is few expect Biden to finish out his term in good physical health, and few expect Trump to finish his term in good mental health.

How did we get here? How has it happened that democracy has come to a point where it seems inadequate to the times?

The short answer is the primary system, or too much democracy at the wrong level.

The primary system isn’t working. It is throwing up the extreme and the incompetent; it is a way of supporting a label, not a candidate. If a candidate faces a primary, the issue will be narrowed to a single accusation bestowed by the opposition.

What makes for a strong democracy is representative government — deliberation, compromise, knowledge and national purpose.

The U.S. House is an example of the evil that the primary system has wrought. Or, to be exact, the fear that the primary system has engendered in members.

The specter of former Rep. Liz Cheney, a conservative with lineage who had the temerity to buck the House leadership, was cast out and then got “primaried” out of office altogether, haunts Congress.

No wonder the political class shelters behind the leaders of yesterday, men unprepared for tomorrow, as a new and very different era unfolds.

There is a sense in the nation that things will have to get worse before they get better. A troubled future awaits.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Breakfasts are best there

Pastel pictures by Ann Wickham, in pastels show at Long River Gallery, White River Junction, Vt., May 1-July 3.

Feds name Southeastern New England 'Ocean Tech Hub'

Central entrance at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth’s New Bedford campus.

— Photo by Ogandzyuk

Edited from a New England Council report

“Recently, the U.S. Economic Development Administration named Rhode Island and Southeastern New England as one of 31 Tech Hubs, calling it the ‘Ocean Tech Hub’. These Tech Hubs bring together public, private and academic partners into collaborative consortia to drive regional growth. The Ocean Tech Hub will focus on the autonomous systems industry and specialize in ocean robotics, sensors and materials in Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

“The hub also received a Tech Hubs Strategy Development Grant that will help the consortium increase local coordination and further manufacturing, commercialization and deployment efforts. About $500,000 of the grant funding is being put towards the hub’s ‘Grow Blue Initiative,’ which is working toward building the Southeastern New England economy through building a diverse and equitable industry to bolster commercial resilience, creating a diverse range of job opportunities, and utilizing internal and external partnerships.

“‘With big implications for climate adaptation and change mitigation, national security, and economic development, this opportunity impacts our startups, researchers, and workforce—and has implications for childcare, transportation, and housing needs,’ said Daniela Fairchild, the chief strategy officer at the quasi-public Rhode Island Commerce Corp.’’

Spring insurrection

Already blooming on south-facing slopes along the streets in Providence.

But they’re smart!

Octopus opening a container with a screw cap.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Now this will be a battle. A Spanish company wants to raise octopuses for food. Delicious and high protein. But research over the past few years has suggested that the animals are highly intelligent and have complex emotions. (Reminder: Pigs and cattle have emotions too, and pigs, anyway, are fairly intelligent. And would you eat your dog? Well, I suppose it depends….)

An inducement for raising the eight-legged and very flexible beasts is that these short-lived creatures grow very fast.

So there’s a campaign to block this aquaculture. So far, I’m on the octopuses’ side. Also, I wonder if there are other creatures in the ocean (besides marine mammals) that we’ll discover are smart.

In Greenwich, displaying a violent world

“Samurai Helmet” (Japan’s Edo Period — 1603-1868), in the show “Arms and Armor: Evolution and Innovation,’’ at the Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Conn., March 7-Aug. 11.

The museum says:

‘‘‘Arms and Armor’ brings together historical weaponry and natural history specimens to highlight parallels between combat in the human and natural worlds.’’

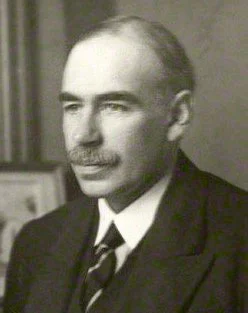

David Warsh: The outside helpers who helped make Keynes and Friedman iconic

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946).

Keynes was a key participant at the Bretton Woods conference, which lay the foundation for much of the world’s financial system after the devastation of World War II.

The conference took place at the Mount Washington Hotel. Clouds here obscure the summits of the Presidential Range.

— Photo by Shankarnikhil88

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman traveled different paths to become the dominant policy economists of their respective times. In The Academic Scribblers, in 1971, William Breit and Roger Ransom invoked the motto of the Texas Rangers to explain Friedman’s success: “Little man whip a big man every time if the little man is right and keeps a’comin’.”

But there was more to it than that.

Both Keynes and Friedman were slow starters and late bloomers. “It was The Economic Consequences of the Peace [in 1919] that established Keynes’s claim to attention”, as biographer Robert Skidelsky wrote at the beginning of the second volume of his trilogy. In murky circumstances, the prescient warning about the hard terms imposed on Germany after World War I failed to be recognized with a Nobel Prize for Peace, as Lars Jonung has shown. Not until 1936, with the appearance of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, when he was 58, did Keynes acquire the sobriquet that Skidelsky confers on him in that second tome, “the economist as savior.”

Friedman was 50 when, in 1962, he published both Capitalism and Freedom and, with Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960. He was nearly 40 when he turned to monetary theory. Within the profession he enjoyed growing success in the ‘50’s and ‘60’s. But vindication and celebrity waited until 1980, when he turned 69, as Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker battled inflation under a monetarist banner; when Friedman’s television series Free to Choose, with his economist wife, Rose. was broadcast on America’s public network; and when Ronald Reagan was elected president.

Both Keynes and Friedman freely offered advice to American presidents, which only enhanced the economists’ stature. Keynes, at arm’s length, disparaged Woodrow Wilson; encouraged Franklin Roosevelt, whom he admired, and, 15 years after his death, saw his policies adopted by John F. Kennedy. Friedman, after a 1964 unsuccessful campaign with Barry Goldwater, enjoyed considerable influence with Richard Nixon and Reagan.

So, how did the Keynesian Revolution roll out in America? There are many accounts of the process by economists, but only one by an economic historian of how America’s leading most trusted newspaper columnist first resisted, then was convinced, and facilitated the movement’s acceptance for the next 40 years. (Michael Bernstein’s A Perilous Progress: Economics and public purpose in twentieth century America (Princeton University Press, 2001) surveys the period from a somewhat different angle.)

Walter Lippmann was already America’s foremost public intellectual, a common enough species today, but then more or less one of a kind. He published A Preface to Politics a year after graduating from Harvard College, studied Thorstein Veblen and Wesley Clair Mitchell, made friends with Keynes when both attended the Versailles Peace Conference, in 1919, compared notes with U.S. presidents, Supreme Court justices, scientists, philosophers, central bankers, lawyers, corporate leaders and Wall Street financiers.

Lippmann began writing an influential newspaper column in the Depression year of 1931. For a taste of how different that world was from our own. I recommend a viewing of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. In Walter Lippmann: Public Economist (Harvard, 2014) the late Craufurd Goodwin, of Duke University, traces the twists and turns of Lippmann’s columns as he sorted through various explanations of the Great Depression – too much free trade, too little gold, too many monopolies, unbalanced budgets, before becoming convinced that more public public spending was the key to recovery.

After World War II, Lippmann grew close to MIT’s Paul Samuelson. He tracked the debates of emerging “neo-liberal” factions, including leaders F. A. Hayek and Friedman, but declined to join the Mont Pelerin Society. His influence as a columnist finally came to grief over his prolonged support for the War in Vietnam, and he died, at 85, in 1974.

The sources of Friedman’s support are more complicated. Within the profession he had many key allies– his Rutgers professors Arthur Burns, later chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, and Homer Jones, later research director of Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; his graduate school friends, George Stigler and Allen Wallis; his brother-in-law Aaron Director, later dean of the University of Chicago’s Law School; his co-author Anna Schwartz; and, of course, his wife, economist Rose Director Friedman, to name only his closest associates. These were among his fellow Texas Rangers.

It has been Friedman’s acolytes outside the profession who were quite different from those of Keynes. The story of the law and economic movement has been well told by Steven Teles in The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The battle for control of the law. On the financialization of markets, no one has yet topped Peter Bernstein’s Capital Ideas: The improbable origins of modern Wall Street. Friedman’s contribution to globalization is discussed in Three Days at Camp David: How a secret meeting in 1971 transformed the global economy, by Jeffrey Garten. The story of various business anti-regulation and anti-tax lobbying groups can be found in Free Enterprise: An American history, by Lawrence Glickman

It’s not that economics departments weren’t also special-interest groups, but they are special interests of a different sort, organized as competitors, which permits swift reversals within the profession itself. Whether that is the case with the legal, financial, corporate, and media industries remains to be seen. Maybe; maybe not.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

'Can't fill a house'

“Winter night,’’ by Bror Lindh (1877-1941), Swedish artist

“An Old Man’s Winter Night,’’ by Robert Frost (1974-1963)

ll out of doors looked darkly in at him

Through the thin frost, almost in separate stars,

That gathers on the pane in empty rooms.

What kept his eyes from giving back the gaze

Was the lamp tilted near them in his hand.

What kept him from remembering what it was

That brought him to that creaking room was age.

He stood with barrels round him—at a loss.

And having scared the cellar under him

In clomping there, he scared it once again

In clomping off—and scared the outer night,

Which has its sounds, familiar, like the roar

Of trees and crack of branches, common things,

But nothing so like beating on a box.

A light he was to no one but himself

Where now he sat, concerned with he knew what,

A quiet light, and then not even that.

He consigned to the moon,—such as she was,

So late-arising,—to the broken moon

As better than the sun in any case

For such a charge, his snow upon the roof,

His icicles along the wall to keep;

And slept. The log that shifted with a jolt

Once in the stove, disturbed him and he shifted,

And eased his heavy breathing, but still slept.

One aged man—one man—can’t fill a house,

A farm, a countryside, or if he can,

It's thus he does it of a winter night.

‘The very three a.m.’

“The Thaw” (1991), by Nikoklay Anokhin

‘‘The most serious charge which can be brought against New England is not Puritanism, but February.... Spring is too far away to comfort even by anticipation, and winter long ago lost the charm of novelty. This is the very three a.m. of the calendar.’’

— Joseph Wood Krutch (1893-1970), American essayist, critic and naturalist. In the 1940s, he lived in Redding, Conn.

Snowdrops piercing the snow.

The circle route

“ Intermezzi, Opus IV, Bl. 12: Amor, Tod und Jenseits (love, death and beyond) ‘‘ (1881), etching and aquatint on paper, in the show “50 Years and Forward: Works on Paper Acquisitions,’’ at the Clark Art Institute, Willliamstown, Mass., through March 10.

In gorgeous Williamstown.

Williamstown in the 1880’s.

If only we’d worn wetsuits

“The Wake” (1964), by Maine-and-Pennsylvania-based painter Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009), in the show “Stories of the Sea,’’ at the Currier Museum of Art, in Manchester, N.H.

The museum says the show:

“{B}rings together a number of extraordinary loans with a wide array of artworks and objects from the museum’s permanent collection in order to explore various maritime themes.

“The selection spans the 16th Century to the present day, and includes dramatic seascapes painted in the Romantic tradition; images of steamers and transoceanic travels, referencing migration and tourism; representations of harbors and shipyards; and poetic tributes to the hardships endured by men working at sea.’’

Chris Powell: Hoping for a reality transfusion about medical debt

— Photo by SantyBoyMX

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont is acting as if he has a magic wand that can eliminate $650 million or more in medical debt owed by unfortunate state residents. He has been waving that wand for more than a year and waved it again the other week in his address to the new session of the state General Assembly. The magic is taking longer than expected.

The idea is for state government to pay $6.5 million to a charitable organization that purchases uncollectible medical debt from hospitals, whereupon the charity will offer the hospitals 1 cent per dollar of debt and the hospitals will agree to sell at that rate. Then the charity will inform debtors that they are off the hook.

But society won't be off the hook. For medical debt won't really be extinguished at all by this mechanism but merely transferred -- transferred to everyone else who uses hospitals. Indeed, uncollectible medical debt is already effectively transferred to the rest of hospital patients, private insurers and government insurers through the higher rates hospitals need to keep operating. Services have been provided without payment and their costs have to be recovered somehow.

While hospital rates must be negotiated with insurers and the government, as vital public institutions the hospitals can't be allowed to fail. State government is already deeply involved in negotiations to arrange Yale New Haven Health's purchase of three hospitals looted by the predatory investment company that acquired them several years ago -- Waterbury Hospital, Manchester Memorial Hospital and Rockville General Hospital. A direct or indirect subsidy to Yale from state government may be necessary.

As a practical matter most hospitals in Connecticut are already government agencies, with the government controlling most of what they do, either through statute, regulation, or insurance and reimbursement rates. Just this week the state Office of Health Strategy ordered Sharon Hospital not to close its money-losing maternity ward. A state government that claims the power to order a hospital to operate a maternity ward can claim the power to order forgiveness of medical debt and set debt forgiveness terms.

Key questions about the governor's debt forgiveness idea remain to be answered.

Will hospitals sell much of their debt so cheaply? They haven't said.

Will government-facilitated forgiveness of medical debt incentivize more people to stiff the hospitals serving them? That seems likely, since the proposed income limits for people qualifying for debt forgiveness are far above poverty thresholds.

Perhaps most important, since state government already has such power over hospitals, what's the need for a charitable organization to serve as intermediary in debt forgiveness?

The answer seems to be to provide political cover and obscure what will be going on -- the transfer of debt from individuals to the public and the concealment of more of the cost of government in the cost of living.

If state government arranged medical debt forgiveness and qualifications directly, by statute or regulation, the program would compete directly and clearly with all other demands on state government's finances. Every state budget might be forced to determine how much medical debt is to be forgiven each year.

Instead an intermediary would disperse the expense of debt forgiveness in thousands of transactions, distributed unequally among hospitals, which in turn would distribute the expense unequally in hundreds more transactions with insurers, government agencies, and hospital labor contracts. Political responsibility and blame would land mainly on hospitals.

Why does medical-debt relief need such subterfuge? For the problem is a terrible consequence of the country's medical insurance system, whose creakiness is exposed every day by "Go Fund Me" or similar campaigns on behalf of people with catastrophic injuries or diseases whose treatment costs far exceed any insurance coverage.

Though individuals or families may be blameless, just victims of bad luck, medical debt can follow them for lifetimes, ruining their credit.

Government is supposed to do for the people the crucial things they can't do for themselves. Covering medical care in catastrophic circumstances should be one of them. Let it be done directly, frankly, and without apology.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

John O. Harney: Remembering my brother; ‘safe for blueberrying’

Robert Harney

My oldest brother Robert, historian, social observer and role model, died nearly 35 years ago after an unsuccessful heart transplant. One doctor quipped that there was not a heart big enough to replace Bob’s.

Memories of my childhood feature Bob’s summer visits to the North Shore … Essex clams, tennis, various adventures on the coast. Also my visits to him in Toronto, where he led the Multicultural History Society of Ontario and introduced me to seemingly limitless exotic culinary experiences.

I still often have questions I wish I could ask Bob on issues ranging from family history to world tensions. I can imagine his presumably sharp and funny take on the explosion in amateur ancestry.

After being surprised at how little Bob’s important work intersected with the age of the Internet, I was recently cheered to see many references to Bob’s work.

But even with all his fascinating work in multiculturalism, it’s Bob’s humanity that sticks with me. Check out this poem of his …

Blueberries

It took the better half of the day

to reach the woods and piggery

up beyond the Lynn road

blueberrying with Capt.

He knew the route. the sun,

prickly shrubs and soggy spots.

He knew the granite outcroppings

beneath the berry bushes

the snakes nesting there—

garter, milk, and copperhead.

He overturned the stones with sticks

making startled humus steam

and baby snakes wriggle

like green tendrils at low tide

of shorewall seaweed.

Beyond the ledge was the piggery fence.

Sows and swill, the farmer’s share

of Salem’s scavenger economy.

The sun made us giddy, the brambles stung

we dreamed Capt.’s tales of bears and lynx,

and so a grunting sow, a piglet’s squeal,

a towhee rustling through the leaves

made the stooping berrypickers freeze.

My sister and I believed in bears

in Salem’s woods.

The old man’s stories made us surer,

gave circumstances and color to the dream.

The fear we knew to be untrue,

for what they didn’t convert,

the Puritans drove away or slew,

and that included beasts as well as men.

Then to show our own descent,

our links in time and space to them.

We threw the little snakes by handfuls

as morsels for the hungry sows

propitiating bears and

exorcizing woods.

Making the ledge

forever safe for blueberrying.

John O. Harney is a writer and retired executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Penobscots' deal with 'Mother Earth'

Penobscot beaded moccasins.

Speech by Penobscot Nation Chief Saugama to the Maine legislature, in Augusta, Maine, on April 6, 2002:

To all who are present here today and to those who may listen on the radio or TV, I ask that your ears hear my words so that you will know what I have said. I ask for your minds to be open so that you will understand my intent. I ask that your hearts feel my commitment to bring honor to my family, my tribe and to our state, a place we all share as our home.

Woliwoni. Thank you.

It is an honor and a privilege as Saugama, the Chief of the Penobscot Nation, to be here on this historic day, addressing the joint session of the 120th Legislature.

Woliwoni. Thank you.

Today symbolizes what I truly believe to be a new era in Tribal/State relations. Relationships are based on communication. Today we have the opportunity for direct communication. Perhaps, today this can be the start of our greatest days before us.

My grandfather was a pack-basket maker, a river guide, and a hunter and worked on the Penobscot log drives. My grandmother, along with raising a large family, tended a garden, and braided sweet grass for the fancy-basket makers. In my youth, I was fortunate enough to have spent many hours with them, hearing the stories of the old days. From my grandparents, as well the other tribal elders, I learned my culture. Though these elders have joined our ancestors, their values, and their passion for preserving our traditions live on in the pride of my people.

I am thankful for my mother, a proud Penobscot woman. In her 60-plus years of living on the Penobscot River, she has witnessed many changes for our people. She faced the bitter winds of winter while walking across the ice, and paddled across the quick spring currents to go to and from school. She drove her first car across the infamous one-lane bridge. My mother worked as hard as many in the Old Town shoe factories and then became a dedicated Penobscot Nation's Tribal Clerk of 19 years. She has always supported my endeavors, even standing in the cold November rains at my High School football games. (Incidentally, she could never understand why 22 young men would fight over one funny shaped small ball.) She always strived to make a better life for her family and her people. Though she could not be here today due a slight heart attack, she will be watching on public TV. Please join me in honoring a proud Penobscot woman, Lorraine Dana. Neyan Penawepskewi. I am Penobscot.

Over the last two years, our people and our concerns for the environment, especially the rivers in the State of Maine have been in the news. We have a special relationship with the Penobscot River. We all live along the river. However, my people not only live on the river, we are actually a part of the river, living on Indian Island. The river is ingrained in our history, our culture, and our values.

It was once told to me by an elder that, before there was a river there were streams, from the upland into the valley. But one day, the water in the valley became a trickle, and it disappeared, and the people grew thirsty. A young hunter went to find out what had happened. He entered the forest and walked for days until he came to the place where the streams converged, and there he saw Kci Cetwalis, a gigantic frog. The frog grew bigger and bigger as it lapped up the little streams. The people sent for Gluskabe, our hero. Gluskabe followed the trail and when he came to the frog he called out, "There are others who are thirsty too. You must learn to share." "I won't stop," croaked Kci Cetwalis the frog, "Because I am the biggest and most powerful, I can do what I want."

Gluskabe pulled up a giant white pine, and lifting it high over his head he brought it down, striking the frog on the back. Kci Cetwalis the frog burst into a thousand pieces. The water shot up into the air and landed in the deep furrow in the ground the tree had made, and the water began to flow. And that is how the Penobscot River came to be.

For centuries our history and culture have been shaped by our direct daily interaction with this powerful moving force of nature. For this reason, my people have always viewed the regulation and protection of our natural resources as our obligation, our stewardship to Mother Earth. We still use the river as a source of life. Our traditions are tied into this powerful free-flowing source. Though Kevlar and Rogallex have all but replaced birch bark canoes, we still use the waterways of the Penobscot to journey north to our sacred monument, Katahdin. Katahdin is the center to our spirituality. We still gather plants from the river's sediments and use them in our medicines. We still take our children upriver to enjoy the traditions of our people. We pray for the return of the salmon so our subsistence rights can be realized.

Our stewardship and protection of the river comes naturally to me and my people. We have a deal; Mother Earth provides for us and we protect her. This traditional value goes beyond laws and regulations. This is a deal that transcends governments, profits and the perception of power. And this is a relationship our people will never break.

Our rivers, our waters are not just a resource, they are us. Our waters are sacred, not just to the Penobscot, not just to the Passamaquoddy, Maliseets, or Mic macs, but to all the people of Maine. Enforcement of the Clean Water Act is absolute and must be addressed. The daily lives and health of people who live along the Penobscot River from Millinocket to Searsport must be protected. We have the Governor's pledge to give the Tribes a substantial and useful role in the process of waste-water discharge permits affecting our reservation. On behalf of the Penobscot Nation I commend the Governor for that. I pledge to work on a government-to-government basis with Attorney General Steven Rowe to find a solution.

It is not enough to have high standards for the cleanliness of the water and the protection of all those who rely upon those waters, including the people of my tribe, the people of Maine, the fish and turtles that live within the river and eagles who find their sustenance within those fish. We are al1 connected and to protect this connection for now and forever. It is not enough to write high standards. They must be enforced. Our lives are at stake, and our environment is at stake. The reputation of the State of Maine is at stake, and as leaders we all have an obligation to protect our most precious resource.

Now I'd like to talk about sovereignty and the Settlement Act. These things are important to us, but need not be scary for you. The Penobscot Nation as a tribe and a government predates the State, and the United States. The State of Maine from 1820 on did recognize us as a tribe, but did not recognize our Federal Indian Rights. This changed in 1975 when Federal Judge Edward Gignoux ruled that the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy Nations have the same sovereign status under the Constitution and laws of the United States as tribes in other parts of the country.

In 1980 we settled our land claims after four long and often bitter years of negotiation. The settlement confirmed our sovereignty and our protection as tribes under Federal Law. The plan of the settlement was that tribes and the State would work out their destiny together. The Federal government gave its advance blessing to any agreements worked out between the tribes and the State.

We haven't done this enough. Too often we have been locked in the ancient struggle of the land claim. We need to find ways to work together as partners. We need to creatively use the tools available to us for the benefit of all. We need to ensure Maine tribes are never again deprived of benefits that other tribes enjoy. We can do this within the context of our unique relationship.

The very essence of tribal sovereignty is the ability to be self-governing for the protection of the health, safety and welfare of our people. We are a distinct people with a unique history. The Penobscots are an Indian people. For thousands of years, the bones of our ancestors have been laid to rest along the shores of the rivers and the ocean. We will continue to safeguard these rights to preserve our future. We are proud of our history and we are hopeful for our future. We, the Penobscot people, the Penobscot Nation are still here, and we will continue to be here for now, and forever. Neyan Penawepskewi. I am Penobscot.

Woliwani. I thank you.