‘Metaphor for life’

“Towards a Blue Planet” (color pencil on wood), by Massachusetts artist Stacey Cusher, in the group show “Everything Leaves a Mark,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, April 3-28.

She says in her artist statement:

“Trees, forests and flowers are iconic and an endless source of inspiration. In drawing these, I locate different textures and emphasize the shapes of trees and differing values in graphite or blue color pencil to speak to their sturdiness and the capacity to withstand these times. They’re a metaphor for life. We have a constant relationship with them. As Sara Maitland, author of From The Forest, describes, “[r]ight from the beginning, the relationship between people and forest [and flora] was not primarily antagonistic and competitive, but symbiotic.”

“And from the slow process of creating drawings, floral paintings and animal portraits found in these gardens, forests and in unexpected places, a meditative presence occurs. There is a grandeur in nature and a spirit. Creating scenic worlds, even in still life paintings, segue into wonder, daydreaming, and contemplation. A child-like feeling occurs when anything seems possible: infinite immensity and infinite possibilities.’’

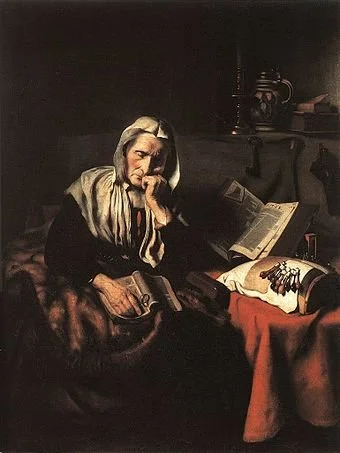

Judith Graham: Maybe we just don’t care about old people

“Old Woman Dozing,’’ by Nicolaes Maes (1656), at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

The COVID pandemic would be a wake-up call for America, advocates for the elderly predicted: incontrovertible proof that the nation wasn’t doing enough to care for vulnerable older adults.

Navigating Aging focuses on medical issues and advice associated with aging and end-of-life care, helping America’s 45 million seniors and their families navigate the health care system.

To contact Judith Graham with a question or comment, click here.

The death toll was shocking, as were reports of chaos in nursing homes and seniors suffering from isolation, depression, untreated illness, and neglect. Around 900,000 older adults have died of COVID to date, accounting for 3 of every 4 Americans who have perished in the pandemic.

But decisive actions that advocates had hoped for haven’t materialized. Today, most people — and government officials — appear to accept COVID as a part of ordinary life. Many seniors at high risk aren’t getting antiviral therapies for COVID, and most older adults in nursing homes aren’t getting updated vaccines. Efforts to strengthen care quality in nursing homes and assisted living centers have stalled amid debate over costs and the availability of staff. And only a small percentage of people are masking or taking other precautions in public despite a new wave of covid, flu, and respiratory syncytial virus infections hospitalizing and killing seniors.

In the last week of 2023 and the first two weeks of 2024 alone, 4,810 people 65 and older lost their lives to covid — a group that would fill more than 10 large airliners — according to data provided by the CDC. But the alarm that would attend plane crashes is notably absent. (During the same period, the flu killed an additional 1,201 seniors, and RSV killed 126.)

“It boggles my mind that there isn’t more outrage,” said Alice Bonner, 66, senior adviser for aging at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. “I’m at the point where I want to say, ‘What the heck? Why aren’t people responding and doing more for older adults?’”

It’s a good question. Do we simply not care?

I put this big-picture question, which rarely gets asked amid debates over budgets and policies, to health care professionals, researchers, and policymakers who are older themselves and have spent many years working in the aging field. Here are some of their responses.\

The pandemic made things worse. Prejudice against older adults is nothing new, but “it feels more intense, more hostile” now than previously, said Karl Pillemer, 69, a professor of psychology and gerontology at Cornell University.

“I think the pandemic helped reinforce images of older people as sick, frail, and isolated — as people who aren’t like the rest of us,” he said. “And human nature being what it is, we tend to like people who are similar to us and be less well disposed to ‘the others.’”

“A lot of us felt isolated and threatened during the pandemic. It made us sit there and think, ‘What I really care about is protecting myself, my wife, my brother, my kids, and screw everybody else,’” said W. Andrew Achenbaum, 76, the author of nine books on aging and a professor emeritus at Texas Medical Center in Houston.

In an environment of “us against them,” where everybody wants to blame somebody, Achenbaum continued, “who’s expendable? Older people who aren’t seen as productive, who consume resources believed to be in short supply. It’s really hard to give old people their due when you’re terrified about your own existence.”

Although covid continues to circulate, disproportionately affecting older adults, “people now think the crisis is over, and we have a deep desire to return to normal,” said Edwin Walker, 67, who leads the Administration on Aging at the Department of Health and Human Services. He spoke as an individual, not a government representative.

The upshot is “we didn’t learn the lessons we should have,” and the ageism that surfaced during the pandemic hasn’t abated, he observed.

Ageism is pervasive. “Everyone loves their own parents. But as a society, we don’t value older adults or the people who care for them,” said Robert Kramer, 74, co-founder and strategic adviser at the National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care.

Kramer thinks that Boomers are reaping what they have sown. “We have chased youth and glorified youth. When you spend billions of dollars trying to stay young, look young, act young, you build in an automatic fear and prejudice of the opposite.”

Combine the fear of diminishment, decline, and death that can accompany growing older with the trauma and fear that arose during the pandemic, and “I think covid has pushed us back in whatever progress we were making in addressing the needs of our rapidly aging society. It has further stigmatized aging,” said John Rowe, 79, professor of health policy and aging at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

“The message to older adults is: ‘Your time has passed, give up your seat at the table, stop consuming resources, fall in line,’” said Anne Montgomery, 65, a health-policy expert at the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare. She believes, however, that baby boomers can “rewrite and flip that script if we want to and if we work to change systems that embody the values of a deeply ageist society.”

Integration, not separation, is needed. The best way to overcome stigma is “to get to know the people you are stigmatizing,” said G. Allen Power, 70, a geriatrician and the chairman in aging and dementia innovation at the Schlegel-University of Waterloo Research Institute for Aging in Canada. “But we separate ourselves from older people so we don’t have to think about our own aging and our own mortality.”

The solution: “We have to find ways to better integrate older adults in the community as opposed to moving them to campuses where they are apart from the rest of us,” Power said. “We need to stop seeing older people only through the lens of what services they might need and think instead of all they have to offer society.”

That point is a core precept of the National Academy of Medicine’s 2022 report Global Roadmap for Healthy Longevity. Older people are a “natural resource” who “make substantial contributions to their families and communities,” the report’s authors write in introducing their findings.

Those contributions include financial support to families, caregiving assistance, volunteering, and ongoing participation in the workforce, among other things.

“When older people thrive, all people thrive,” the report concludes.

Future generations will get their turn. That’s a message that Kramer conveys in classes he teaches at the University of Southern California, Cornell, and other institutions. “You have far more at stake in changing the way we approach aging than I do,” he tells his students. “You are far more likely, statistically, to live past 100 than I am. If you don’t change society’s attitudes about aging, you will be condemned to lead the last third of your life in social, economic, and cultural irrelevance.”

As for himself and the baby boom generation, Kramer thinks it’s “too late” to effect the meaningful changes he hopes the future will bring.

“I suspect things for people in my generation could get a lot worse in the years ahead,” Pillemer said. “People are greatly underestimating what the cost of caring for the older population is going to be over the next 10 to 20 years, and I think that’s going to cause increased conflict.”

Judith Graham is a reporter for KFFHealth News.

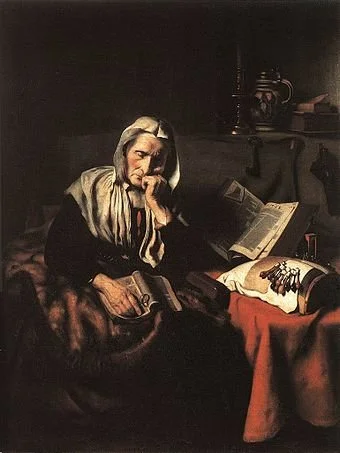

‘Fun and Games’ in New London

“Girl in Crash Helmet’’ (polychromed wood and masonite), by the late Ivoryton, Conn.-based artist Leo Jensen (1926-2019), in the show “Fun and Games: Leo Jensen’s Pop Art,’’ at the Lyman Allyn Museum, New London, Conn., Feb. 10-April 14.

— Image courtesy of Mr. Jensen’s estate

The museum says:

“Recognized for his dynamic contributions to pop art, Connecticut artist Leo Jensen drew on his experiences growing up in the circus and the rodeo to bring the excitement and allure of that world into his art. With a fertile imagination and wide-ranging artistic skills and interests, the Ivoryton-based Jensen worked in various media—painting, drawing, carving, and welding—with equal enthusiasm.”

Best known for his large-scale bronze frog sculptures on the Thread City Crossing Bridge in Willimantic, Conn., Leo Jensen brought humor, nuance and insight into his work. This show presents a selection of Jensen’s artwork from his long and productive artistic career. It’s organized in conjunction with the Florence Griswold Museum, in Old Lyme, Conn., whose companion exhibition “Fun and Games? Leo Jensen’s Pop Art,” will be on view there from Feb. 20 through May 19.

One of Leo Jensen’s four copper frogs on the Thread City Crossing Bridge (aka Frog Bridge), in Willimantic.

The Ivoryton Playhouse, in Leo Jensen’s town.

Boston women’s shelter gets boost from foundation created by former Red Sox owners

Edited from a New England Council report

“The Pine Street Inn has used some of the $15 million it has received from the Yawkey Foundation to help expand and otherwise improve the women’s shelter, in Boston’s South End. The Yawkey family were long-time owners of the Boston Red Sox.

“The $15 million award represents the largest single donation in the Pine Street Inn’s 55-year history. After getting the donation, Pine Street is getting going on its plan to add 400 to 500 new units of permanent housing over the next five years, which will mark about a 40 percent expansion in its capacity. This increase will arrive at a crucial juncture, as Boston faces the dual challenges of an influx of migrants and escalating housing costs.

“‘Even this isn’t enough, but it’s a beginning,’ said Pine Street Inn President Lyndia Downie. Pine Street and Yawkey Foundation officials recently gathered at the women’s shelter to celebrate the late Jean Yawkey’s 115th birthday through the naming of the ‘Yawkey House.’ More than 1,300 women are supported each year through Pine Street’s outreach. It hopes to help more.’’

Don’t expect perfection

OIiver Ellsworth in 1785.

“Let us, my fellow citizens, take up this constitution with the same spirit of candour and liberality; consider it in all its parts; consider the important and advantages which may be derived from it, and the fatal consequences which will probably follow from rejecting it. If any objections are made against it, let us obtain full information on the subject, and then weigh these objections in the balance of cool impartial reason. Let us see, if they be not wholly groundless; But if upon the whole they appear to have some weight, let us consider well, whether they be so important, that we ought on account of them to reject the whole constitution. Perfection is not the lot of human institutions; that which has the most excellencies and the fewest faults, is the best that we can expect.’’

— Oliver Ellsworth (1745-1807), whose hometown was Windsor, Conn., was a Founding Father of the United States, lawyer, judge, politician and diplomat. He was a framer of the U.S. Constitution, senator from Connecticut, and the third chief justice of the United States. His remarks here came on Dec. 17, 1787, during the campaign to ratify the Constitution.

Oliver Ellsworth Homestead, in Windsor. It’s now a historical museum.

‘Chronological markers’

“Coded #000000 [Black]”, by Triton Mobley, in the show “Coloured Aesthetica,’’ at the Chazan Gallery at Wheeler, Providence, through March.

— Image courtesy of the Chazan Gallery

The gallery says:

Triton Mobley is a new media artist whose practice pulls together "critical making methodologies across performative installations, programmable fabrications, and speculative industrial design…. Mobley's work in the show is digital but pulls from the tangible and real to trace "chronological markers across the archived memories from America’s amalgamation of public, private, racial, economic, and religious spaces."

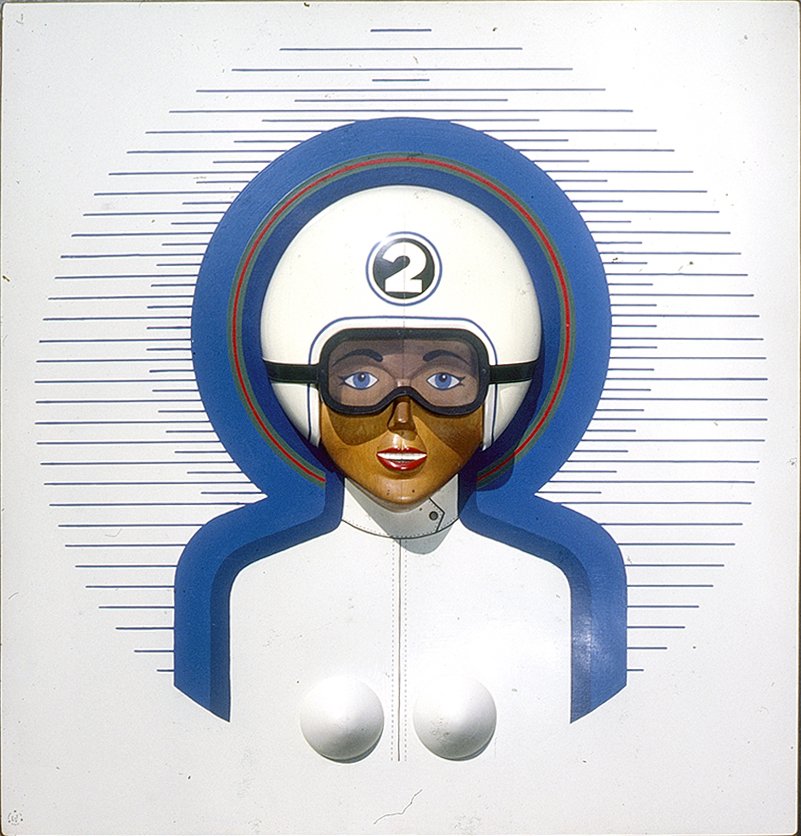

‘Hammers hoisted’

The factory of International Silver Company (1898–1983), later known as Insilco Corp., was formed in Meriden as a corporation banding together many existing silver companies in the immediate area and beyond. The making of silver products was once a major industry in New England. Consider that Taunton, Mass., dubbed itself “The Silver City.’’

“Till the thudding source, exposed,

Counfounded in wept guesswork:

Framed in windows of Main Street's

Silver factory, immense

”Hammers hoisted, wheels turning….’’

— From “Night Shift,’’ by Massachusetts-raised poet Sylvia Plath (1932-1963). To read the whole poem, please hit this link:

https://allpoetry.com/Night-Shift

GOP mulls ‘Slayveree’; See haunting bas relief in Boston

From the National Park Service:

The Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial, installed in 1884, a haunting bronze bas relief on the Boston Common, and created by famed sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, commemorates the first Black regiment from the North in the Civil War. Although African Americans served in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, Northern racist sentiments kept African Americans from taking up arms for the United States in the early part of the Civil War. However, a clause in Abraham Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation allowed for the raising of Black regiments. Gov. John Andrew soon created the Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry. He chose Robert Gould Shaw, the son of wealthy abolitionists, to serve as its colonel. Notable abolitionists including Frederick Douglass and local leaders such as Lewis Hayden recruited men for the 54th Regiment. African Americans enlisted from every region of the north, and from as far away as Canada and the Caribbean.

Through their heroic, yet tragic, assault on Fort Wagner, S.C., on on July 18, 1863, in which Shaw and many of his men died, the 54th helped erode Northern public opposition to the use of Black soldiers and inspired the enlistment of more than 180,000 Black soldiers into the Union’s forces.

The front of Linden Place, the Bristol, R.I., mansion built in 1810 for infamous slave trader (and other “cargoes”), privateer and ship owner Gen. George DeWolf and designed by architect Russell Warren. The mansion now operates as a historic house museum.

— Photo by Bbucco/ Tiffany Axtmann Photography

‘Collide and co-exist’

Work by Jennifer Moses in her show “In Brightest Day in Blackest Night,’’ at the Museum of Art at the University of New Hampshire, Durham.

The museum says:

“Jennifer Moses explores opposing visual and conceptual themes which both collide and co-exist—the comic vs. the tragic, line vs. shape, and flatness vs. the illusion of space. Moses's work combines abstraction and representation, most recently shifting from personal reflection to political expression.’’

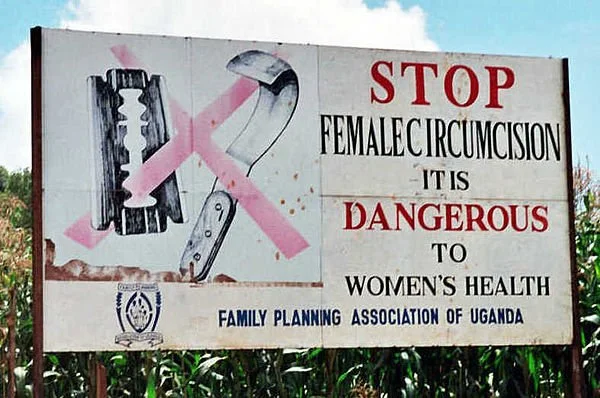

Chris Powell: Mutilation is mutilation; social-service industry complains about fiscal ‘guardrails’

Transsexual woman July Schultz displaying her palm with "XY" written on it at an demonstration.

MAN CHESTER, Conn.

What’s the difference between “female genital mutilation” and “gender-affirming care”?

“Female genital mutilation” is an ancient barbaric practice prevailing in some cultures in Africa and the Middle East. Some adherents mistakenly think that Islam requires it. It is committed against minor females and is euphemized as “purification.”

“Gender-affirming care” is the euphemism for sex-change therapy and is a modern barbaric practice associated with politically correct cultures in North America and Western Europe. It is committed against minors of both sexes and involves anatomy-altering drugs and surgery.

Female genital mutilation is prohibited by federal law and 41 states but not by Connecticut, so last week state legislators, 30 civic groups, and victims of the practice announced that they again will try to have it outlawed in the forthcoming session of the General Assembly. Legislators are rushing to endorse the proposal, though following the dubious practice of states that outlaw abortion, the advocates of outlawing female genital mutilation in Connecticut also want the law to criminalize taking a minor out of state for mutilation.

But meanwhile there is no effort in the legislature to prohibit “gender-affirming care” for minors, though Connecticut law presumes that minors lack the judgment to make such serious decisions, prohibiting them from purchasing alcohol, tobacco, and guns and from entering contracts and getting tattoos.

Medical research increasingly connects bad physical and psychological outcomes with “gender-affirming care,” and many who received it as minors come to regret it.

So in their consideration of female genital mutilation, legislators should ask why surgical and chemical mutilation and alteration shouldn’t be forbidden for all minors, delaying such practices to adulthood. What’s bad for the young goose is bad for the young gander as well, regardless of political correctness and however many other genders there are imagined to be.

DON'T WHINE, SPECIFY: Connecticut's social-services industry is complaining about the "fiscal guardrails” that state government has imposed on itself for the last few years at the behest of Gov. Ned Lamont and leaders of both parties in the General Assembly. The “guardrails” function as the limit on state spending that was promised as an apology for the state income tax in 1991 but was never delivered.

The industry has a point. Paid by state government, the industry provides many services that state government is obliged to provide and does so far less expensively than they would be provided by state government’s own employees, whose compensation is far higher than that of social-service organization employees.

But the industry's complaint is empty, for the industry never specifies any state spending that is less important than its own.

For many years state government has been primarily a pension-and-benefit society for its own employees. By law and union contract the compensation of state employees takes precedence over everything else in state government. Twenty percent of state government’s revenue now is used for government employee pensions, in part because for decades state government bought votes by overpromising while underfunding benefits. The social-services industry didn't object.

Even now much money could be transferred to social services if state government economized with its employees, as by freezing salaries instead of paying generous raises.

But the social-services industry doesn’t press for that either.

Indeed, practically every week brings an announcement from the governor about financial grants from the state to municipalities and other entities for discretionary purposes. Last week’s disbursements included $9 million for roads, sidewalks, and recreation trails in 10 small towns. No one would die if the money wasn’t spent that way. Without the state money the towns might proceed with some of the projects at their own expense.

But the social-services industry could make a plausible assertion that some of its underfunded work is a matter of life and death.

State government is never efficient. It is full of inessential, excessive and patronage spending. The social-services industry should try to earn more money by showing how it could be obtained without more taxes -- that is, by correcting state government’s mistaken priorities.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

They did what they had to do

Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885), in his official presidential portrait, painted in 1875. He was, of course, the greatest Civil War general, and while his presidential reputation was sullied by corruption by some people in his administration, historians in recent years have raised their view of his two terms in office. The ancestors of Grant’s father emigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony from England in the 1630’s.

The greenish-yellow area has been expanding north at an accelerating rate in the past few decades. The climate of New England was considerably colder than now during “The Little Ice Age,’’ 1300-1850.

“They [the Pilgrim Fathers] fell upon an ungenial climate, where there were nine months of winter and three months of cold weather and that called out the best energies of the men, and of the women too, to get a mere subsistence out of the soil, with such a climate. In their efforts to do that they cultivated industry and frugality at the same time—which is the real foundation of the greatness of the Pilgrims.’’

From the speech by Ulysses S. Grant at a New England Society Dinner in New York on Dec. 22, 1880.

Llewellyn King: Cynically denigrating the news media has become a mainstay — attacking the messenger rather than the message

Outside the Reuters news service building in Manhattan

Newspapers "gone to the Web" in California

— Photo by SusanLesch

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

In the 1990s, someone wrote in The Weekly Standard — it may well have been Matt Labash — that for conservatives to triumph, all they had to do was to attack the messenger rather than the message. His advice was to go after the media, not the news.

Attacking the messenger was all well and good for the neoconservatives, but their less-thoughtful successors, MAGA supporters, are killing the messenger.

The news media— always identified as the “liberal media” (although much of the news media are right wing) — are now often seen, due to relentless denigration, as a force for evil, a malicious contestant on the other side.

No matter that there is no liberal media beyond what has been fabricated from political ectoplasm. Traditionally, most news proprietors have been conservative and many, but not most reporters, have been liberal.

It surprises people to learn that when you work in a large newsroom, you don’t know the political opinions of most of your colleagues. I have worked in many newsrooms over the decades and tended to know more about my colleagues’ love lives than their voting preferences.

This philosophy of “kill the messenger” might work briefly but down the road, the problem is no messenger, no news, no facts. The next stop is anarchy and chaos — you might say, politics circa 2024.

Add to that social media and their capacity to spread innuendo, half-truth, fabrication and common ignorance.

There is someone who writes to me almost weekly about the failures of the media — and I assume, ergo, my failure — and he won’t be mollified. To him, that irregular army of individuals who make a living reporting are members of a pernicious cult. To him, there is a shadow world of the media.

I have stopped remonstrating with him on that point. On other issues, he is lucid and has views worth knowing on such subjects as the Middle East and Ukraine.

That poses the question: How come he knows about these things? The answer, of course, is that he reads about them, saw/heard the news on television or heard it on radio.

Reporters in Gaza and Ukraine risk their lives, and sometimes lose them, to tell the world what is going on in these and other very dangerous places. No one accuses them of being left or right of center.

But send the same journalists to cover the White House, and they are assumed to be unreliable propagandists, devoid of judgment, integrity or common decency, so enslaved to liberalism that they will twist everything to suit a propaganda purpose.

That thought is on display every time Rep. Elise Stefanik (R.-N.Y.), an avid Trumper, is interviewed on TV. Stefanik attacks the interviewer and the institution. Her aim is to silence the messenger and leave the impression that she isn’t to be trifled with by the media, shades of Margaret Thatcher. But I interviewed “The Iron Lady,” and I can say she answered questions, hostile or otherwise.

Stefanik’s recent grandstanding on TV hid her flip-flop on the events on Jan. 6, 2021, and failed to tell us what she would do if she were to win the high office she clearly covets.

I have been too long in the journalist’s trade to pretend that we are all heroes, all out to get the truth. But I have observed that taken together, journalists tell the story pretty well, to the best of their own varied abilities.

We make mistakes. We live in terror of that. An individual here and there may fabricate — as Boris Johnson, a former British prime minister, did when he was a correspondent in Brussels. Some may, indeed, have political agendas; the reader or listener will soon twig that.

The political turmoil we are going through is partly the result of media denigration. People believe what they want to believe; they can seize any spurious supposition and hold it close as a revealed truth.

You can, for example, believe that ending natural-gas development in the United States will lead to carbon reduction worldwide, or you can believe that the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection with loss of life and the trashing of the nation’s great Capitol Building was an act of free speech.

One of the more dangerous ideas dancing around is that social media and citizen journalists can replace professional journalists. No, no, a thousand times no! We need the press with the resources to hire excellent journalists to cover local and national news, and to send, or station, staff around the world.

Have you seen anyone covering the news from Ukraine or Gaza on social media? There is commentary and more commentary on social media sites, all based on the reporting of those in danger and on the spot.

This is a trade of imperfect operators, but it is an essential one. For better or for worse, we are the messengers.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

No engineers need inspect

“Harlem Bridge” (oil on canvas), by Anthony Dyke, a Norwich,, Vt., native who lives in Boston, at the “One Plus One’’ show at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Feb. 25.

Clear 'em out

Edited from a Wikipedia report:

The Suffolk County Courthouse, now formally the John Adams Courthouse, in Pemberton Square, in Boston. It houses the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and the Massachusetts Appeals Court. Built in 1893, it was the major work of Boston's first city architect, George Clough, and is one of the city's few surviving late 19th-Century monumental civic buildings.

“In a lesser chamber of Suffolk County Courthouse on a day in early August, 1965 – the hottest day of the year – a Boston judge slammed down his heavy gavel, and its pistol-like report threw the room into disarray. Within a few minutes, everyone had gone – judge, court reporters, blue-shirted police, and a Portuguese family dressed as if for a wedding to witness the trial of their son.’’

— From the short story “Palais de Justice,’’ by Mark Helprin (born 1947), American-Israeli writer

Amy Maxmen: Right wingers' battle against science and facts imperils public health

The American Institute for Economic Research, in the wealthy Berkshires town of Great Barrington, Mass. The right-wing think tank has been a center of anti-science activism, at least when the science is defended by Democrats.

— Photby Dariusz Jemielniak ("pundit")

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

Rates of routine childhood vaccination in America hit a 10-year low in 2023. That, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, puts about 250,000 kindergartners at risk for measles, which often leads to hospitalization and can cause death. In recent weeks, an infant and two young children have been hospitalized amid an ongoing measles outbreak in Philadelphia that spread to a day care center.

It’s a dangerous shift driven by a critical mass of people who now reject decades of science backing the safety and effectiveness of childhood vaccines. State by state, they’ve persuaded legislators and courts to more easily allow children to enter kindergarten without vaccines, citing religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs.

Growing vaccine hesitancy is just a small part of a broader rejection of scientific expertise that could have consequences ranging from disease outbreaks to reduced funding for research that leads to new treatments. “The term ‘infodemic’ implies random junk, but that’s wrong,” said Peter Hotez, a vaccine researcher at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas. “This is an organized political movement, and the health and science sectors don’t know what to do.”

Changing views among Republicans have steered the relaxation of childhood vaccine requirements, according to the Pew Research Center. Whereas nearly 80% of Republicans supported the rules in 2019, fewer than 60% do today. Democrats have held steady, with about 85% supporting. Mississippi, which once boasted the nation’s highest rates of childhood vaccination, began allowing religious exemptions last summer. Another leader in vaccination, West Virginia, is moving to do the same.

An anti-science movement picked up pace as Republican and Democratic perspectives on science diverged during the pandemic. Whereas 70% of Republicans said that science has a mostly positive impact on society in 2019, less than half felt that way in a November poll from Pew. With presidential candidates lending airtime to anti-vaccine messages and members of Congress maligning scientists and pandemic-era public health policies, the partisan rift will likely widen in the run-up to November’s elections.

Dorit Reiss, a vaccine policy researcher at the University of California Law San Francisco, draws parallels between today’s backlash against public health and the early days of climate change denial. Both issues progressed from nonpartisan, fringe movements to the mainstream once they appealed to conservatives and libertarians, who traditionally seek to limit government regulation. “Even if people weren’t anti-vaccine to start with,” Reiss said, “they move that way when the argument fits.”

Even certain actors are the same. In the late ’90s and early 2000s, a right-wing think tank, the American Institute for Economic Research, undermined climate scientists with reports that questioned global warming. The same institute issued a statement early in the pandemic, grandly called the “Great Barrington Declaration.” It argued against measures to curb the disease and advised everyone — except the most vulnerable — to go about their lives as usual, regardless of the risk of infection. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, warned that such an approach would overwhelm health systems and put millions more at risk of disability and death from COVID. “Allowing a dangerous virus that we don’t fully understand to run free is simply unethical,” he said.

Another group, the National Federation of Independent Business, has fought regulatory measures to curb climate change for over a decade. It moved on to vaccines in 2022 when it won a Supreme Court case that overturned a government effort to temporarily require employers to mandate that workers either be vaccinated against covid or wear a face mask and test on a regular basis. Around 1,000 to 3,000 COVID deaths would have been averted in 2022 had the court upheld the rule, one study estimates.

Politically charged pushback may become better funded and more organized if public health becomes a political flashpoint in the lead-up to the presidential election. In the first few days of 2024, Florida’s surgeon general, appointed by Ron DeSantis, the former Republican and still Florida governor, called for a halt to use of mRNA covid vaccines as he echoed DeSantis’s incorrect statement that the shots have “not been proven to be safe and effective.” And vaccine skeptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who is running for president as an independent, announced that his campaign communications would be led by Del Bigtree, the executive director of one of the most well-heeled anti-vaccine organizations in the nation and host of a conspiratorial talk show. Bigtree posted a letter on the day of the announcement rife with misinformation, such as a baseless rumor that covid vaccines make people more prone to infection. He and Kennedy frequently pair health misinformation with terms that appeal to anti-government ideologies like “medical freedom” and “religious freedom.”

A product of a Democratic dynasty, Kennedy’s appeal appears to be stronger among Republicans, a Politico analysis found. DeSantis said he would consider nominating Kennedy to run the FDA, which approves drugs and vaccines, or the CDC, which advises on vaccines and other public health measures. Another fotmer Republican candidate for president, Vivek Ramaswamy, had vowed to gut the CDC should he win.

Today’s anti-science movement found its footing in the months before the 2020 elections, as primarily Republican politicians rallied support from constituents who resented such pandemic measures as masking and the closure of businesses, churches, and schools. Then-President Donald Trump, for example, mocked Joe Biden for wearing a mask at the presidential debate in September 2020.

Democrats fueled the politicization of public health, too, by blaming Republican leaders for the country’s soaring death rates, rather than decrying systemic issues that rendered the U.S. vulnerable, such as underfunded health departments and severe economic inequality that put some groups at far higher risk than others. Just before Election Day, a Democratic-led congressional subcommittee released a report that called the Trump administration’s pandemic response “among the worst failures of leadership in American history.”

Republicans launched a subcommittee investigation into the pandemic that sharply criticizes scientific institutions and scientists once seen as nonpartisan. On Jan. 8 and 9, the group questioned Anthony Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in 1984-2022 and a leading infectious-disease researcher. Without evidence, committee member Marjorie Taylor Greene (R.-Ga.) accused Fauci of supporting research that created the coronavirus in order to push vaccines: “He belongs in jail for that,” Greene, a vaccine skeptic, said. “This is like a, more of an evil version of science.”

Taking a cue from environmental advocacy groups that have tried to fight strategic and monied efforts to block energy regulations, Hotez and other researchers say public health needs supporters knowledgeable in legal and political arenas. Such groups might combat policies that limit public health power, advise lawmakers, and provide legal counsel to scientists who are harassed or called before Congress in politically charged hearings.

Other initiatives aim to present the scientific consensus clearly to avoid both-sidesism, in which the media presents opposing viewpoints as equal when, in fact, the majority of researchers and bulk of evidence point in one direction. Oil and tobacco companies used this tactic effectively to seed doubt about the science linking their industries to harm.

Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center, at the University of Pennsylvania, said the scientific community must improve its communication. Expertise, alone, is insufficient when people mistrust the experts’ motives. Indeed, nearly 40% of Republicans report little to no confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interest.

In a study published last year, Jamieson and colleagues identified attributes the public values beyond expertise, including transparency about unknowns and self-correction. Researchers might have better managed expectations around covid vaccines, for example, by emphasizing that the protection conferred by most vaccines is less than 100% and wanes over time, requiring additional shots, Jamieson said. And when the initial covid vaccine trials demonstrated that the shots drastically curbed hospitalization and death but revealed little about infections, public health officials might have been more open about their uncertainty.

As a result, many people felt betrayed when COVID vaccines only moderately reduced the risk of infection. “We were promised that the vaccine would stop transmission, only to find out that wasn’t completely true, and America noticed,” said Rep. Brad Wenstrup (R.-Ohio), chair of the Republican-led coronavirus subcommittee, at a July hearing.

Jamieson also advises repetition. It’s a technique expertly deployed by those who promote misinformation, which perhaps explains why the number of people who believe the anti-parasitic drug ivermectin treats covid more than doubled over the past two years — despite persistent evidence to the contrary. In November, the drug got another shoutout at a hearing where congressional Republicans alleged that the Biden administration and science agencies had censored public health information.

Hotez, author of a new book on the rise of the anti-science movement, fears the worst. “Mistrust in science is going to accelerate,” he said.

And traditional efforts to combat misinformation, such as debunking, may prove ineffective.

“It’s very problematic,” Jamieson said, “when the sources we turn to for corrective knowledge have been discredited.”

Amy Maxmen is a Kaiser Family Health News reporter.

Find shelter where you can

From Chiffon Thomas’s show “The Cavernous,’’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Conn., through March 17.

The museum says:

“Chiffon Thomas’s first solo museum exhibition will unveil a new body of work, including the artist’s first public sculpture. Thomas’s interdisciplinary practice, spanning embroidery, collage, sculpture, drawing, performance, and installation, examines the ruptures that exist where race, gender expression, and biography intersect. Thomas’s practice is informed by his background in education, percussion, and stop motion animation, as well as a childhood steeped in religion.’’

In Ridgefield’s rather spiffy downtown

— Photo by Doug Kerr

A physician’s memoir of a son’s and his own early-onset cancer

Sidney Farber, M.D. (1903-1973), of Children’s Hospital, Boston, with a patient. Dr. Farber, a pediatric pathologist, is regarded as the father of modern chemotherapy. The famed Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, in Boston, is named for him and philanthropist Charles Dana. Some of Dr. George H. Beauregard’s book, Reservation for 9, occurs at Dana-Farber.

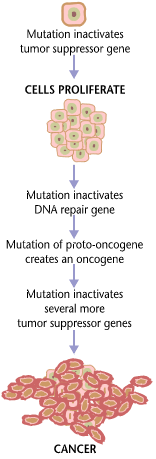

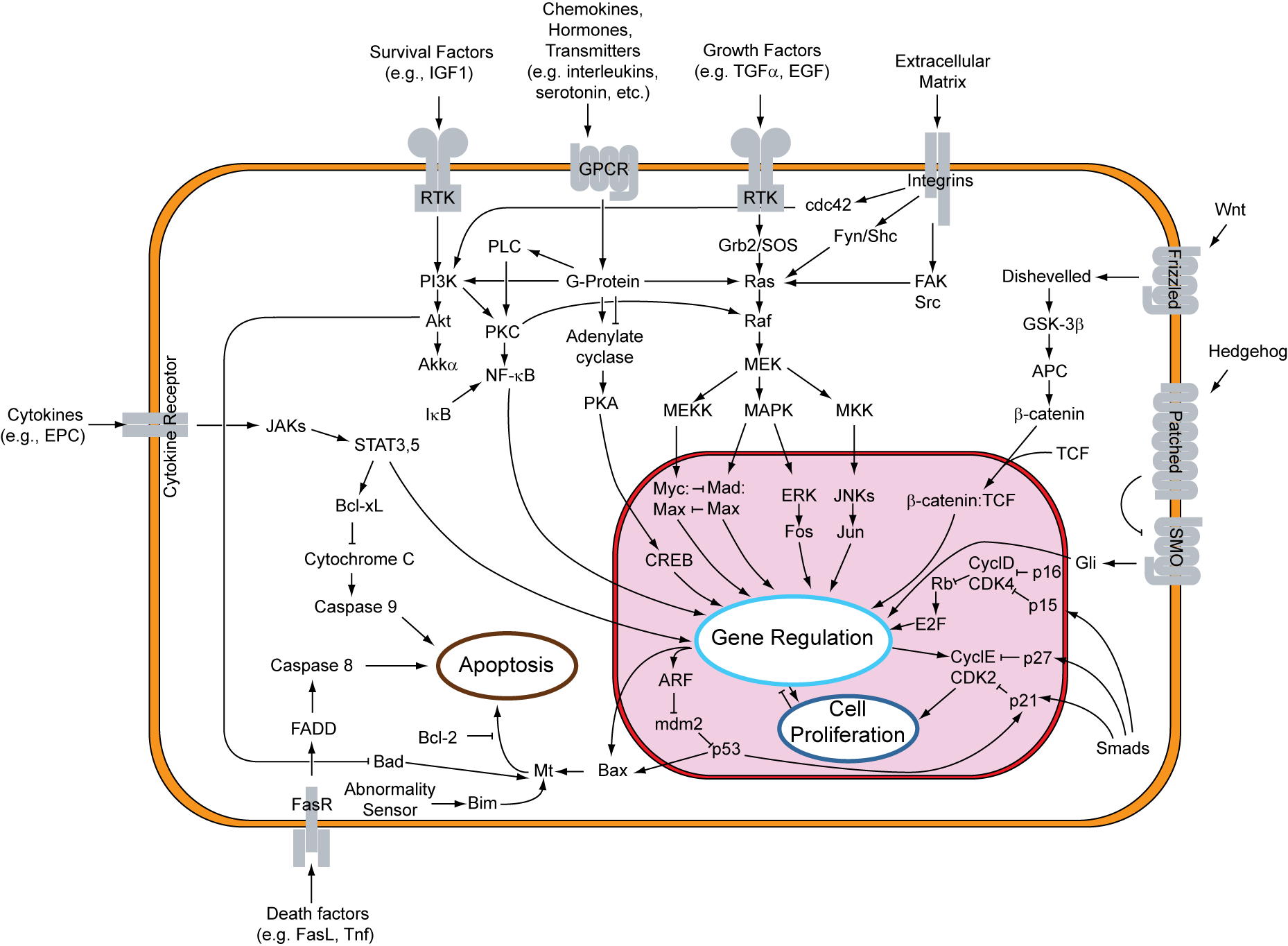

Numerous cell signaling pathways are disrupted in the development of cancer.

— Graphic by Roadnottaken

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I’ve been watching a physician/health-care executive friend, George H. Beauregard, prepare a book, yet to be published, titled Reservation for 9, that’s both a memoir and a medical saga, most of it set in Greater Boston.

The book tells how he and his son Patrick developed different advanced-stage early-onset cancers (early onset defined as cancers diagnosed in patients under 50), creating seismic changes in their lives, and those of their whole colorful nuclear family of six, that accompanied their illnesses. It’s a story about a complex family history, fear, grief and hope, along with the science and institutions of medicine, and provides much insight for others battling the disease.

There has been an alarming global increase in the incidence of cancer affecting younger adults. Patrick’s colorectal cancer was diagnosed when he was 29, and it killed him at 32, but not before he became an inspiring national spokesman for other victims. Dr. Beauregard, for his part, was diagnosed with bladder cancer at age 49 but is now apparently cured.

Patrick’s story continues to be cited in national news media, including recently in The Wall Street Journal.

Appearing as a guest on the Today Show on March 10, 2020, he said:

“In a situation like this, your mind can either liberate you or essentially incarcerate you...and you choose what to make of it.’’

“I don’t see the point in being negative in this. Negativity is only going to bring on more negativity. I choose to have a positive outlook and always have hope, and I don’t see why you would ever decide not to.”

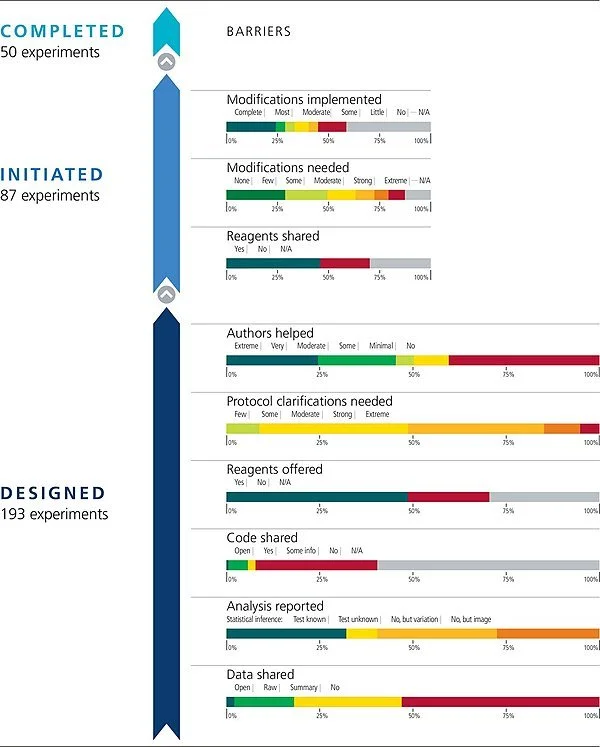

Results from The Reproducibility Project: Cancer biology suggest most studies of the cancer research sector may not be replicable.

‘Getting back my humanity’

Carmichael Hall on the Rez Quad at Tufts

—Photo by Jellymuffin40

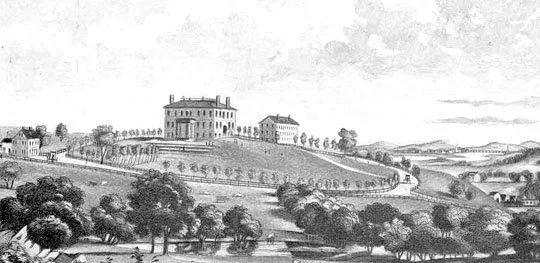

Tufts College circa 1854, on Walnut Hill, soon after its founding, in 1852.

Edited from a report by the New England Council, based on a Boston Globe story

“An initiative by Tufts University, has achieved remarkable success in recent years by allowing inmates to pursue and complete a college education. The Tufts University Prison Initiative at the Tisch College (TUPIT), at Tufts’s main campus, in Medford, Mass., established in 2016, fosters collaboration between Tufts faculty, students, and both incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. This partnership aims to address challenges related to mass incarceration and racial justice. TUPIT also provides a unique opportunity for students who begin their studies while incarcerated to continue and complete their education on the Tufts campus after their release.

“TUPIT was created by Hilary Binda, a senior lecturer at Tufts, and now the program’s executive director. TUPIT also includes the Tufts Educational Reentry Network, MyTERN, an accredited one-year college and reentry program for people post-incarceration.

“One of the program’s graduates, 33-year-old Juan Pagan, said in his graduation speech, ‘Professors affirming that I am worthy and have something positive to offer society is the greatest gift I have ever received. I now know that I can be an asset to my family and community because [the program] helped me gain back that ineffable part of me that prison repressed — my humanity.’’

Success enough?

Skylands, now Martha Stewart’s summer place in Seal Harbor, Maine, was built for auto mogul Edsel Ford.

“Don't give up. Defend your ideas, but be flexible. Success seldom comes in exactly the form you imagine.”

“So the pie isn't perfect? Cut it into wedges. Stay in control, and never panic.’’

― Martha Stewart (born 1941), lifestyle mogui

Travel, time and place

Left ,“Interior V ‘‘ (photograph on aluminum), by Rebecca Skinner. Right, “W. 42nd St.’’ (oil on panel), by Chris Plunkett, in the group show “Travelling,’’ at Fountain Street Fine Art, Boston.

The gallery says:

“‘Travelling’ suggests a sojourn to a destination in some form or another, and the concept of ‘place’ is examined along multiple vectors by this group of artists. Rebecca Skinner’s interior/exterior photographs of abandoned places contain a textural richness revealing a morphological study not merely of paint, brick, and wood, but also the chronological layers of story. The vibrant cityscapes that fluidly leap from the brush of Chris Plunkett….{T}he intensity of his palette turns recognizable metropolitan scenes into urban spectacles out of fondly remembered dreams.’’