Two in Concord

“Self-Portrait” (oil on canvas), by Alet Zielhuis, and “Westcott 3” (acrylic with pencil on paper), by Lizzie Abelson, in their joint show at Concord Art, Concord, Mass., through Feb. 11.

— Image courtesy Concord Art

The gallery says:

“Abelson, a New England native, has followed a path that led her from magazine illustration to her current work depicting liminal spaces that are isolating, foreign yet intimately familiar with muted colors and stark lines. Zielhuis, who grew up in the Netherlands, returned to art later in life and explores life drawing, using what she learned from her time at the Museum of Fine Art and MassArt. ‘‘

Chuck Collins: 'Baby Bonds' can help reduce America's intense concentration of wealth

The old Boston Stock Exchange building. The exchange opened in 1834 and closed in 2007, when it was absorbed by NASDAQ.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

The wealthiest 10 percent of Americans hold about 93 percent of all household stock-market wealth in this country, Axios reported recently — a record high.

The Institute for Policy Studies analyzed Fed data and found that the lion’s share of these gains went to the richest 1 percent alone. This elite group owns 54 percent of public equity markets, up from 40 percent in 2002.

The bottom half of the country? They own just 1 percent.

There’s been a lot of chatter about the “democratization” of the public stock market. The Fed estimates that 58 percent of U.S. households have some money in the stock market, mostly through retirement funds such as IRAs and mutual funds.

But that hype is missing a key trend: Nearly all that wealth controlled by the wealthiest 10 percent of us. As Gillian Tett observed in the Financial Times, “If nothing else, these rising concentrations merit far more public debate, since they challenge America’s self-image of its political economy and financial democracy.”

How do we boost the wealth ownership of the bottom half of households? One bold solution is to establish children’s savings accounts, also known as “Baby Bonds.”

New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker and Massachusetts Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley have introduced the American Opportunity Act, a federal Baby Bond bill. Under this proposal, children would be provided with a $1,000 savings account at birth, with annual contributions up to $2,000, depending on family income.

At the age of 18, the proceeds of these accounts would become available to recipients for educational expenses, purchasing a home, or making investments that provide for long-term returns. For example, those funds could be invested in mutual funds and retirement funds to increase the nest eggs for non-wealthy individuals.

A number of states, such as Connecticut, and a few cities, such as Washington, D.C., are already creating baby bond programs. Others have introduced legislation to create them.

Connecticut has a far-reaching program aimed at reducing the state’s racial wealth divide and boosting the wealth of all low-income households. Starting in July 2023, Connecticut began depositing $3,200 into a trust in the name of each new baby born into a household eligible for Medicaid. The program is known by the acronym HUSKY after the popular state college mascot.

Recipients will be able to redeem that capital between the ages of 18 and 30 if they remain Connecticut residents. The “HUSKY Bonds’’ are projected to grow to between $10,000 and $24,000 in value, depending on when they are withdrawn. The funds will be tax-exempt to the beneficiaries and available for investments such as higher education or job training, homeownership and small business start-ups.

Other states that have either introduced Baby Bond legislation or are seriously considering it include California, Massachusetts, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, Nevada, Washington, Wisconsin and Vermont.

Innovative programs such as these can help bust up the dangerous concentration of wealth at the top of our country’s economic ladder. In an age of unprecedented inequality in this country, it’s an idea whose time has come.

Chuck Collins, based in Boston, directs the Program on Inequality and co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Seeking the security of home

“Voiceless #1’’ (Indiana limestone), in “Passage’’ show, by Nora Valdez, at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., through September, 2025.

The museum says:

“A new installation on the museum grounds, ‘Passage,’ includes four pieces depicting crucial moments in a journey.

“Originally from Argentina, Valdez trained in both Italy and Spain before settling in Boston. Her sculptures represent the nature of change, life of the individual, and the forces that wear upon the human soul. Her immigrant-themed work describes the challenge of those caught within unfamiliar systems who seek the security of home.’’

A new group will address region’s housing shortages

Three-decker housing in Worcester.

The New England Council is pleased to announce the establishment of a new cross-sector Housing Working Group. The new Working Group will bring together council members from various sectors throughout the region to work collaboratively to address the housing shortages plaguing the region.

The New England region faces an unprecedented shortage of housing at all levels – everything from affordable rental units, to middle-income single-family homes. The shortages are having a negative impact on the region’s economy, making it difficult for employers to attract and retain talent, and making the region less attractive for businesses to locate and expand here.

The new Housing Working Group will focus on:

Identifying and supporting federal policy proposals that aim to increase housing supply.

Educating federal policymakers about the impact of the shortages and impediments to solving the crisis.

Fostering collaboration across different sectors and across state lines.

The Working Group is open to any council member who is interested in working on this issue, and will host its first meeting on Thursday, Feb. 15. Council members can register HERE.

If you have any questions about this new initiative, please contact Griffin Doherty, director of Federal Affairs.

Looking for a cellular grave

— Photo by Matteo Corti

“The sparrows sort of rejoice atop the giant stone

crosses. Nobody has a human-sized plastic iPhone

for a grave. I like to think that the sparrows

would enjoy that too.’’

— From “Cemetariot,’’ by Ian Cappelli

Sonali Kolhatkar: Why not control all drug prices?

Food and Drug Administration inspectors at a drug company.

Headquarters of Biogen, the big drug company, in Cambridge, Mass. Greater Boston, primarily Boston and Cambridge, hosts more than 1,000 biotechnology companies, ranging from small start-ups to billion-dollar pharmaceutical companies.

Major pharmaceutical companies in the United States are battling with Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders over an issue that is at the heart of whether we value human wellbeing over corporate profits. As chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP), Sanders has vowed to force CEOs of pharmaceutical companies to publicly answer for why their drug prices are so much higher than in other nations. He plans to bring a committee vote to subpoena them. The subpoenas are necessary because—brazenly—the CEOs of Johnson & Johnson and Merck have simply refused to testify to the HELP committee. What are they afraid of?

In a defensive-sounding letter to Sanders, a lawyer for Johnson & Johnson accused the senator of using committee hearings to “punish the companies who have chosen to engage in constitutionally protected litigation.” The letter does not specify the litigation in question—perhaps because it would sound so ridiculous and would reveal the company’s real agenda. Last July, the company, along with Merck and Bristol Myers Squibb, sued the Biden administration for allowing the Medicare program to regulate prescription-drug prices.

It appears that Johnson & Johnson and Merck are indeed afraid of being questioned by lawmakers about drug-profiteering in the U.S.

One pharmaceutical expert, Ameet Sarpatwari, of the Harvard Medical School, explained to The New York Times that, “The U.S. market is the bank for pharmaceutical companies…. There’s a keen sense that the best place to try to extract profits is the U.S. because of its existing system and its dysfunction.” Another expert, Michelle Mello, a professor of law and health policy at Stanford university, told The Times, “Drugs are so expensive in the U.S. because we let them be.”

In other words, it’s been a free-for-all for pharmaceutical companies in the U.S. In 2003, then-President George W. Bush signed a Medicare reform bill into law, promising help for seniors struggling to pay for medications, but that law stripped the federal government of its power to negotiate drug prices for Medicare’s participants. It was a typically Republican, Orwellian move: Promise help to ordinary people and deliver the exact opposite.

Nearly two decades later, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which Biden signed into law in 2022, tied Medicare drug prices to inflation and required companies to issue rebates if prices rose too fast. It was the first time since Bush’s 2003 law that drug manufacturers were subject to any U.S. price regulations. Pharmaceutical companies aren’t having it, and not only did they sue Biden over the IRA, they don’t seem to want to answer for their actions publicly.

It’s not enough for Medicare to be able to cut drug prices. There needs to be nationwide regulation on all drug prices for all Americans. After all, American taxpayers generously subsidize the research and development of most drugs. A report by Sanders’s staff explained that “[w]ith few exceptions, private corporations have the unilateral power to set the price of publicly funded medicines.” The report’s authors chided that “[t]he government asks for nothing in return for its investment.”

What’s more, the report rightly points out that people in other nations benefit from having access to lower-cost drugs that Americans have paid global pharmaceutical companies to develop. For example, SYMTUZA, an HIV medication that scientists at the U.S. National Institutes of Health helped to develop, is available to U.S. patients for a whopping $56,000 a year, while patients in the UK pay only $10,000 a year for the same drug purchased from the same company.

It’s not as if such companies as Johnson & Johnson have some perverse preference for European patients over American ones. It’s merely that their prices are regulated by most other advanced industrial nations. The U.S. “happens to be the only industrialized nation that doesn’t negotiate” drug prices, explained Merith Basey, executive director of Patients For Affordable Drugs NOW, in an interview on Rising Up With Sonali last fall.

Indeed, countries like the UK, France and Germany, offer models for the U.S. in drug-price controls and much has been written about what works best. Further, there is—unsurprisingly—a strong public desire for price controls. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll in August 2023, “[m]ajorities across partisans say there is not enough regulation over drug pricing.” Moreover, a whopping 83 percent of those polled “see pharmaceutical profits as a major factor contributing to the cost of prescription drugs.”

There is no shortage of ideas for specific price-control regulations that could work in the U.S. For example, the Center for American Progress’s October 2023 report “Following the Money: Untangling U.S. Prescription Drug Financing’’ delves deep into how market prices are determined for medications and suggests interventions at every stage of drug price setting.

Frankly, such complex solutions would not really be necessary if all Americans could simply join Medicare health coverage and if Medicare’s bargaining power to negotiate drug prices could be applied to all drugs. But, in the absence of this commonsense holistic approach to healthcare, even complex price controls would be better than no price controls.

Predictably, conservative capitalist critics have trotted out the same, tired arguments against government price regulations of pharmaceuticals. “Drug Price Controls Mean Slower Cures,” declared a Wall Street Journal editorial headline. The paper’s editorial board called the IRA, “the worst legislation to pass Congress in many years,” and went as far as accusing the Biden administration of “extortion.”

But who is engaging in extortion? Economists studying the pharmaceutical industry have found that for years companies have been so flush with cash that they have spent hundreds of billions of dollars in stock buybacks and exorbitant executive bonuses and pay packages. “The $747 billion that the pharmaceutical companies distributed to shareholders was 13 percent greater than the $660 billion that these corporations expended on research & development over the decade,” wrote William Lazonick and Öner Tulum in a report for the Institute for New Economic Thinking.

Further, The Wall Street Journal’s screed ignores price controls in the U.K., France, Germany and other nations. If those have no bearing on the speed and quality of drug development, why should U.S. price controls have an impact? And if they do have an impact, then Americans are being unfairly required to bear the burden that people all over the world benefit from.

The Journal’s editorial board made one accurate claim, saying that the IRA “will also give companies the incentives to launch drugs at higher prices and raise prices for privately insured patients to compensate for the Medicare cuts.” The paper made this prediction without any comment on unfettered corporate greed. Indeed, if anyone is engaging in de facto extortion, it appears as though pharmaceutical companies may be the guilty parties in punishing Americans for price controls.

Pharmaceutical companies launched the new year with announced price hikes on at least 500 medications—a massive effort at gouging the public. In contrast, the IRA’s drug-price controls apply to only 10 medications so far, and will be expanded to 15 drugs per year for the next four years, and 20 drugs per year thereafter.

Rather than removing price controls on the paltry numbers of medications the IRA can regulate, an easy fix is to apply those same regulations to most or all drugs. Best of all, in order for such a solution to be implemented, pharmaceutical company CEOs wouldn’t even have to drag themselves into committee hearings to explain away their corporate greed.

Sonali Kolhatkar is a multimedia journalist. She is the founder, host and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a weekly television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations.

'Between the natural and the manmade'

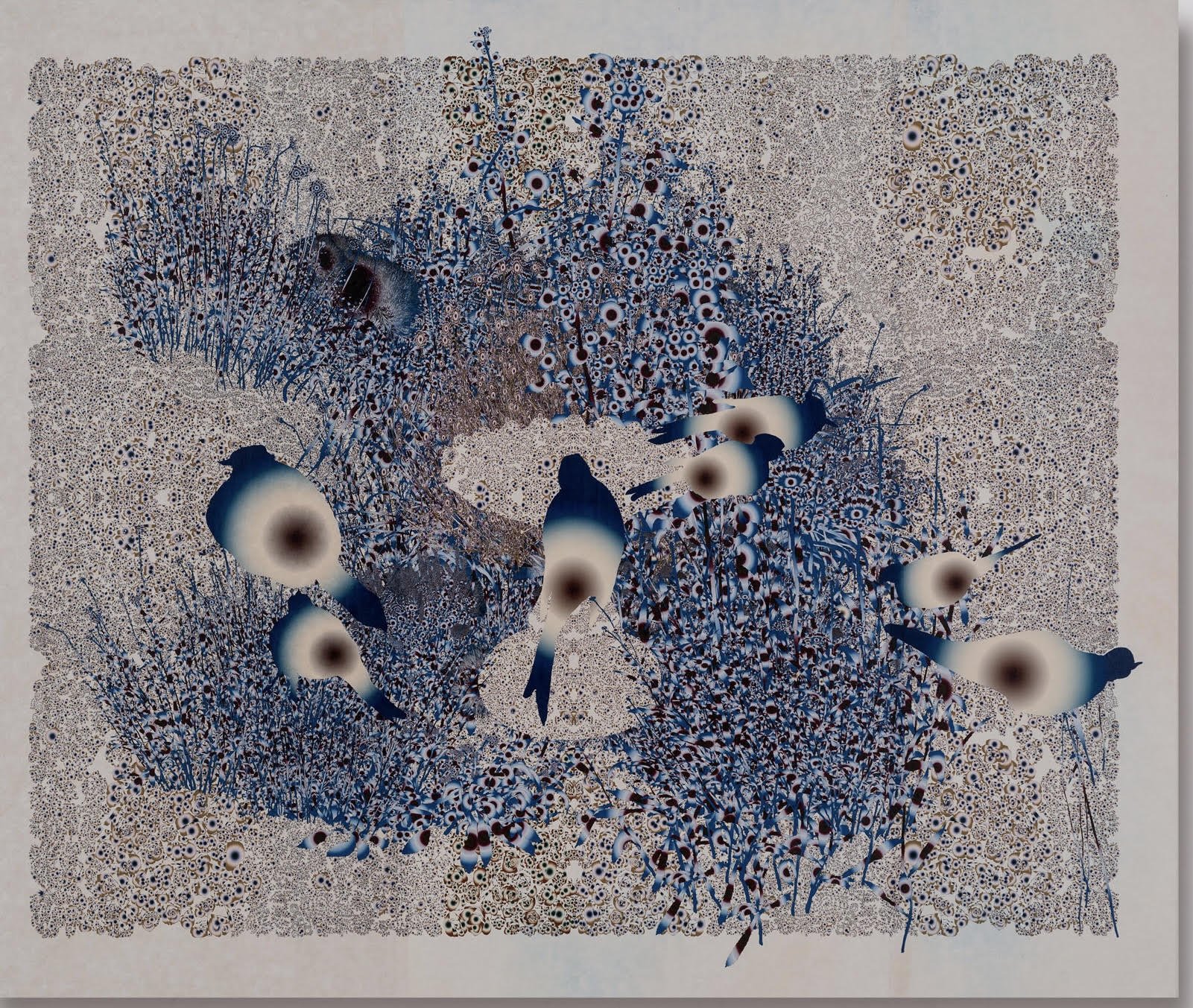

“Fountain II’’ (pigment print, mulberry paper on linen), by Andy Millner, in his show “Floating World; The Light the Bird Sees,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, Greenwich, Conn., Feb. 24-April 6.

The gallery says”

“Millner’s work investigates the relationship between art and nature, the natural and the manmade. He began by using traditional pigmented materials on canvas to convey the complexity of lines and contours seen in organic forms, such as flowers, leaves or trees.’’

Bring it on

Vegetation can cause snow-melting heat.

— Photo by Wing-Chi Poon

“Recent research has demonstrated that the {January} thaw is a reality and most frequently occurs between Jan. 20 and Jan. 26….Though the thaw does not come every year, it has put in an appearance often enough to establish its place as a singular factor of the New England climate.’’

-- From “The New England Weather Book’’ (1976), by David Ludlum and the editors of Blair & Ketchum’s Country Journal (RIP)

“ There are two seasonal diversions that can ease the bite of any winter. One is the January thaw. The other is the seed catalogues.

—- Hal Borland (1900-1978), American nature writer. He spent most of his adult life living in Salisbury, Conn.

xxx

“My sense of time seems to be melting, like a kid's snowman in a January thaw.’’

— Stephen King (born 1947), Maine-based novelist

1908 postcard

Salisbury, Conn., in the Litchfield Hills, has long been a favorite weekend refuge.

Icy ingenuity

What the “Artful Ice Shanties’’ exhibit of the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum & Art Center will look like during the Feb. 17-25 event — if it’s cold enough.

The museum says:

“The show is is a place-based celebration of artistic talent, creative ingenuity, and the rich history of ice fishing in New England. The Artful Ice Shanties will be displayed at Retreat Meadows, the ice across the street from Retreat Farm (45 Farmhouse Square, Brattleboro).

“Visitors are welcome from dawn to dusk. Park at Retreat Farm, stop in at the welcome hut near the farmhouse, and then head out onto the ice to see the shanties.

“On Saturday, February 24, at 3 p.m., join us for an Awards Ceremony, where a panel of local judges will give out an array of light-hearted awards.

“This is the fourth year of Artful Ice Shanties. Prior year’s entries have included:

“ — Namaskônek, a shanty inspired by the Algonquin ancestors of the region

“ — A glass box that used recycled lenses to simulate the experience of the northern lights

“ — A shanty by third and fourth graders that displayed animals’ winter survival strategies

“ — An enormous black die with moon-shaped dots

“ — A shanty that doubled as a working camera obscura

“ — A shanty in the shape of a giant fish.

“Check out these photos from 2021, 2022, and 2023.

“This project was inspired in part by Art Shanty Projects in Minneapolis.”

Chris Powell: ‘Baby bonds’ are doomed to fail

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont and state Treasurer Erick Russell this week invited the state to celebrate a disaster. They announced with rejoicing that almost 8,000 children born in Connecticut since last July 1 have qualified automatically for state government's "baby bonds" program by virtue of the coverage extended to their parents by Medicaid, government medical insurance for the poor.

Another 15,000 children are expected to be born into Medicaid -- that is, born into poverty -- in Connecticut this year, and 15,000 or more every year after that in perpetuity. Wonderful!

Most parents whose households get Medicaid were unprepared to support children in the first place. Such households are usually headed by unmarried women whose children have little if any commitment from fathers. With its "baby bonds" program at least state government acknowledges that such households are where poverty begins.

So now Connecticut is investing $3,200 on behalf of each new Medicaid baby in the expectation that the bond's value will increase to $11,000 or more by the time the child reaches age 18, whereupon the beneficiary will be able to liquidate the bond for cash for higher education, purchase of a home, or investment in a business or retirement plan.

“In just six months the first-in-the-nation Connecticut baby bonds program has put more than 7,000 working families on a pathway to the middle class and is transforming the future of our state," the governor said. "This gives our young people startup capital for their lives and ultimately will help break the cycle of intergenerational poverty for thousands of families.”

The governor's forecast makes some happy assumptions: that escaping poverty is mainly about access to cash and that the beneficiaries of baby bonds will reach 18 well-parented, well-educated, skilled and employable enough to make their own way in the world, and not demoralized from neglect at home and in trouble with the law.

The Department of Children and Families, the courts and the Correction Department know better than such assumptions about kids born into Medicaid.

The baby bonds program also assumes that its beneficiaries will reach 18 knowing how to manage money. Since even the program's advocates recognized the shakiness of that assumption, baby bond recipients are to be required to pass a test of financial literacy, at least if the people running the program 18 years hence remember to devise one.]

‘

But recipients of baby bond cash will not be required to have mastered basic courses in high school, nor even to have graduated from high school. Indeed, linking baby bond cash with educational success would have made the case for the program much stronger. But such a link would have impugned all public primary education in Connecticut, whose main policy is just social promotion.

Treasurer Russell acknowledged that baby bonds are not a "silver bullet" and that breaking the cycle of poverty will require far more action. "How we support those kids along the way will go a long way in determining how prepared they are to seize this opportunity," Russell said. So he has organized a study committee about that.

Such an inquiry should have long preceded baby bonds.

For starters it should have asked how children are diverted from poverty by a welfare system that rewards childbearing outside marriage, depriving them of fathers, and by schools that advance them without requiring them to learn anything.

What most improves a child's chances is well documented: a stable family with two devoted parents who know the necessity of education and work and who set the right examples. The children of such families long have avoided poverty without baby bonds.

As the governor notes, young people going out into the world need some capital to get started with. But the better part of that capital is not the money thrown at problems by elected officials too lazy or scared to examine them. The better part of that capital is intangible: what is put into the minds and character of children as they grow up.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

A safe place

“Beacon 3, 2018 (concrete, wood, paper and light fixture), by Derrick Adams, in his show “Sanctuary,’’ at the Middlebury (Vt.) College Museum of Art, Jan. 26-April 14.

— Image courtesy of Mr. Adams and Gagosian

The museum says:

“This exhibit consists of 50 works of mixed-media collage, assemblage on wood panels, and sculpture that reimagine safe destinations for the black American traveler during the mid-20th Century. The work was inspired by The Negro Motorist Green Book, an annual guidebook for black American road-trippers published by New York postal worker Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1967, most of which was during the Jim Crow era.”

Agassiz’s ‘three stages of scientific truth’

Louis Agassiz, in 1870, at Harvard

A collection of bird specimens at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, which used to be named for Louis Agassiz.

“Every great scientific truth goes through three stages. First, people say it conflicts with the Bible. Next they say it has been discovered before. Lastly they say they always believed it.”

xxx

“I cannot afford to waste my time making money.”

― Louis Agassiz (1807-1873), Swiss-born American biologist and geologist and Harvard professor. He was among the first scientists to discover the impact of ice ages.

Depiction of the Laurentide Ice Sheet covering most of Canada and the northern United States.

Mural goes multisensory

Mural by Sante Graziani at the D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, in Springfield, Mass.

The museum explains:

“Sante Graziani submitted the winning design to a mural competition hosted by the Springfield Museums. The artist’s mural, which was painted in 1947 and celebrates Springfield’s vibrant artistic community, remains on view in its original location at the D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts. In celebration of the 75th anniversary of Graziani’s mural, the Springfield Museums invite visitors to explore a custom-made tactile reproduction of the artwork. This multisensory interactive includes buttons and sensors that activate audio recordings and encourage visitors to engage with the mural through touch and sound.’’

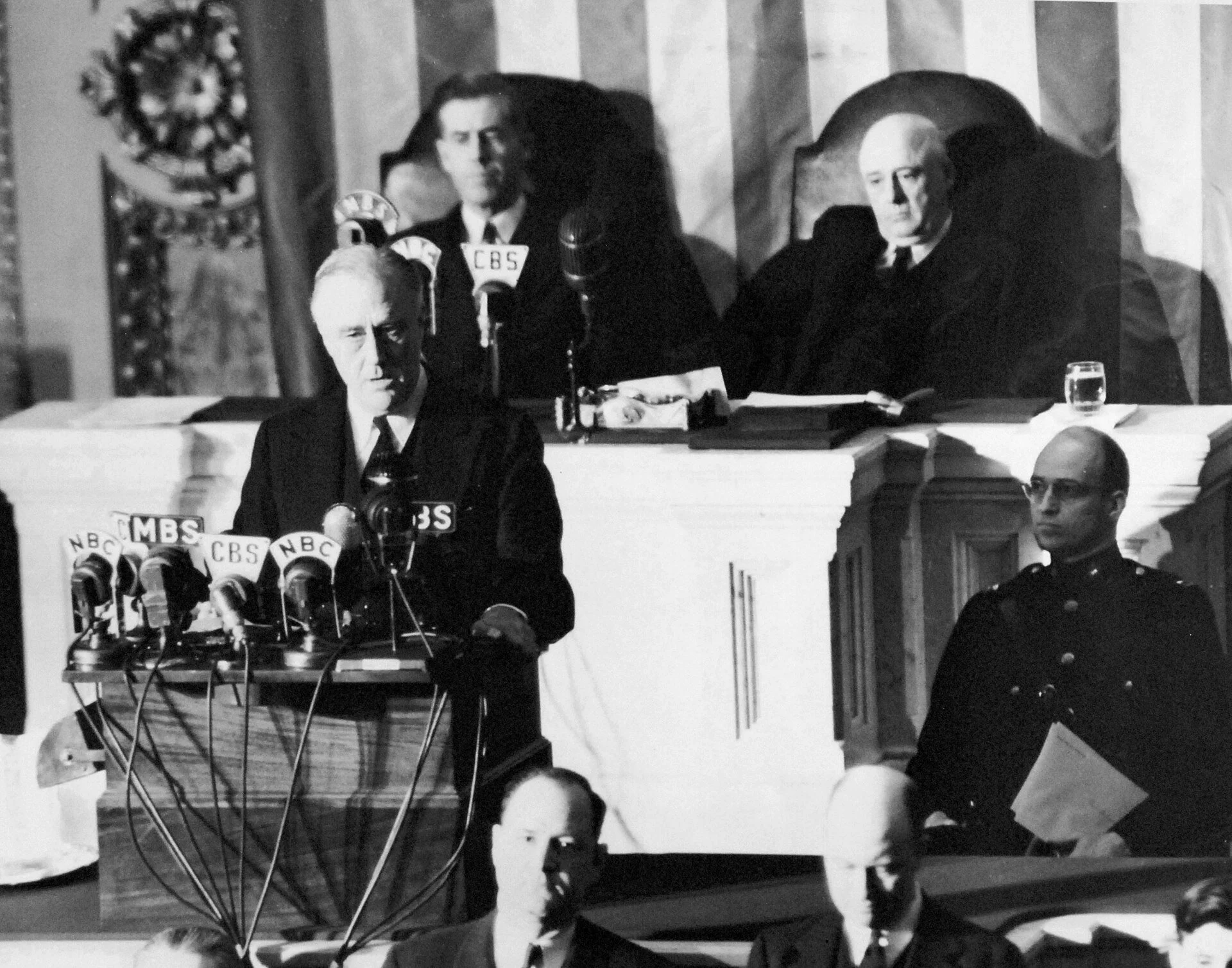

Llewellyn King: Needed — great speeches on great issues

President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivering his “Day of Infamy” speech, on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor pulled America into World War II.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I wonder whether my hearing is failing. Should I get it tested?

In this seminal presidential election year, I don’t hear the answers from either side about the issues bearing down on the country.

The over-coverage of the Iowa caucuses was in direct proportion to the candidates’ avoidance of the great matters that the victor will have to deal with in the Oval Office.

If the Republicans are off down the yellow brick road of the Wizard of Donald Trump, the Democrats are well along a road of political ruin, believing that they won’t win unless Trump is imprisoned or removed from the ballot. That represents a negative political dynamic.

Neither political caravan has emphasized there are great issues ahead that, if they were to embrace, would lead on to victory.

Trump is sure he has the formula, and he may be right. Grievance, his and those of the voters — vast, shapeless grievance — propels the Republicans forward: Unhappy about something? Trump is your man.

Biden’s message is to vote for more of the same. That should be a message enough because the Biden years have been overall good years with an economy that is growing despite inflation and woes abroad.

Whereas for Trump everything is a platform, everything a bull horn, for Biden no message is getting out. He is in the chorus when he should be the lead singer.

Questions about Trump’s fitness for office are muted and questions about Biden’s – mostly his age — are front-and- center. It is asymmetrical, but it is what it is.

It is up to the Democrats to turn their fortunes around, beyond waiting for Trump to fall. Trump is a political phenomenon, and his Republican and Democratic opponents need to accept that.

Meanwhile, huge issues are begging for attention. Here are just five:

How to prepare for artificial intelligence and its boost to productivity set against its threat to jobs.

How to accommodate the impact of climate change. Should we build seawalls in vulnerable cities along the coasts? Can Boston, New York, Miami and San Francisco be physically defended against rising seas?

The looming matter of Taiwan. Will we defend it or will we let it fall to China? The stakes are appeasing China or going to war — world war.

The housing crisis. This is a here-and-now issue that should be at the top of the Democratic agenda. This is a people issue like abortion. People have nowhere to live and that should be a gift to any politician.

Immigration writ large, not just as a crisis at the Southern border. It is a world issue in which every war, drought, coup, recession and religious purge worsens as more people from Africa, Asia, Central and South America, and the Middle East seek a better life — but often just life itself. We can seal the border, but the undocumented will still arrive. Migrants are pitiable, as are all refugees, but they are flooding the stable countries of the world so fast they endanger those countries. It is conquest by migration.

The candidates haven’t delivered great speeches on these or other issues, let alone a series of speeches which would move the electorate and the country. Nothing echoes from the rafters when Biden, Kamala Harris, Nikki Haley, or Ron DeSantis speak. It is small-bore stuff, no cannons.

Politics in democracies is carried forward by great speeches which raise new issues, redefine old ones and shiver the timbers of the electorate. Think Washington, Lincoln, both Roosevelts, Churchill, De Gaulle, Kennedy, Reagan and Thatcher and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. They carried the day with rhetoric and found their place in history with words.

Trump's speeches are just Trump, part of the phenomenon, part of the cascade of disinformation. Biden’s sound — as I am sure they are — written by committee, like corporate press releases. And, oh, Harris reduces everything to incoherence. Haley and DeSantis have been hobbled by a disinclination to take on Trump frontally.

The big issues are hanging out like ripe fruit, ready to be plucked by any candidate with the nous to do so and craft a speech or several. None have I heard.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

‘The domestic sea’

“Looking West” (photomontage on aluminum) in Deer Isle, Maine, artist Jeffrey C. Becton’s show “Framing the Domestic Sea,’’ through May 5, at the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

— Image courtesy of Mr. Becton

The museum says that Maine-based Mr. Becton is inspired by the “history of New England, maritime scenes and contemporary ecological issues. His work, digital montages of coastal scenes and New England views, is printed on aluminum and evokes a surreal, dream-like quality that is simultaneously unsettling and - for those who call New England home - very familiar.’’

‘No time for hazy notions’

The Wood River Inn, in Wyoming. R.I. On the National Register of Historic Places, it was built in 1850.

“Miss Rainy Roth of Wyoming Rhode Island, did not believe in luck. Sixty one years old, a self-sufficient woman with a business of her own, she had no time for hazy notions. People who believed in sudden strokes of good fortune, she thought, were simply seeking an excuse for idleness.’’

— From the short story “Rue,’’ by Susan Dodd (born 1946), American writer

‘That unite us all’

“Boy From Kezi, Zimbabwe’’ (acrylic and acrylic ink on canvas), by Amy E. Kindler, at River Stones Custom Framing, Rochester, N.H., Feb. 1 to Feb. 28.

The gallery says:

“Amy E. Kindler’s masterful strokes bring to life the narratives of men, women, and children worldwide. Kindler celebrates the rich tapestry of faces, characters, and stories that unite us all with the intention of conveying the profound message of God’s love for the entire human race.’’

The Cocheco River provided power for Rochester’s early factories in the 19th Century.

— Photo by AlexiusHoratius

Those crazy crystals

An early classification of snowflakes by Israel Perkins Warren (1814-1892), Congregational minister as well as an editor, author and amateur scientist who lived in Connecticut and then in Maine.

Winters can be an inconvenient bore while also providing some days of glittering beauty and austere clarity and the clearest nights of the year to see the stars. In any case, winters are getting shorter, and along with that, there’s less snow as we continue to cook the world by burning gas, oil and coal.

To people like me who have generally found shoveling snow tedious (and now, with age and heart disease, dangerous) and icy streets and sidewalks narrowed by piles of snow frustrating to navigate, the accelerating shrinkage of snow might seem pleasant (though I’m a former skier). But snow and cold are part of a healthy environment in the North Temperate Zone.

Consider that snow helps store reliable fresh-water supplies for drinking and crops. Its blanket protects the plants below it, and cold winters are part of the annual cycle essential for growing many fruits, among other edibles.

There’s an old adage that “snow is the poor man’s fertilizer,’’ based on the fact that as snow melts, it slowly releases nitrogen into the ground, while protecting the underlying plants from a killing freeze. Much of the nitrogen in rainfall washes away.

And besides facilitating winter sports, a major industry in such places as northern New England, winter and snow make us enjoy spring all the more. (Snow-making strikes me as an environmentally dubious activity – using lots of energy, causing some erosion and sometimes screwing up local water systems. But, hey, it is exhilarating to bounce down a mountain, even if the land on each side of the “snow”-covered trail is brown.)

Of course, heating bills can be onerous, but so can electricity bills for air conditioning as summery temperatures tend to start earlier and end later.

Meanwhile, of course, even as global warming continues, there will still be cold snaps; one will be coming this week. There’s weather and then there’s climate. Remember when the sci-fi-sounding “polar vortex” deep freeze in the Northeast (apparently caused by warming around the North Pole!) very briefly drove our temperatures below zero last winter? Things quickly warmed up again to above “normal’’, whatever that is these days, but not before killing some plants that had been lured into acting (do plants “act”?) as if spring had arrived. One of our favorite flowering shrubs died in this way, though the others seemed unaffected.

All Wet

This 18th Century house in Newport’s frequently flooded Point section was the headquarters of French Vicomte de Noailles 1780-1781, during the Revolutionary War.

Will localities and states have to start taking many thousands of properties along shorelines of rivers and the ocean by eminent domain as these places repeatedly flood? Just in Rhode Island, you see the same places flooding again and again and again with taxpayers having to absorb some of the cost of repair. People like to live along the water, but this can’t go on.

Things will get particularly interesting if the powers-that-be try to permanently evacuate such upscale places as Newport’s Point neighborhood, with its gorgeous 18th Century houses. But I suppose that wouldn’t happen for a few decades….Right? Get out those stilts!

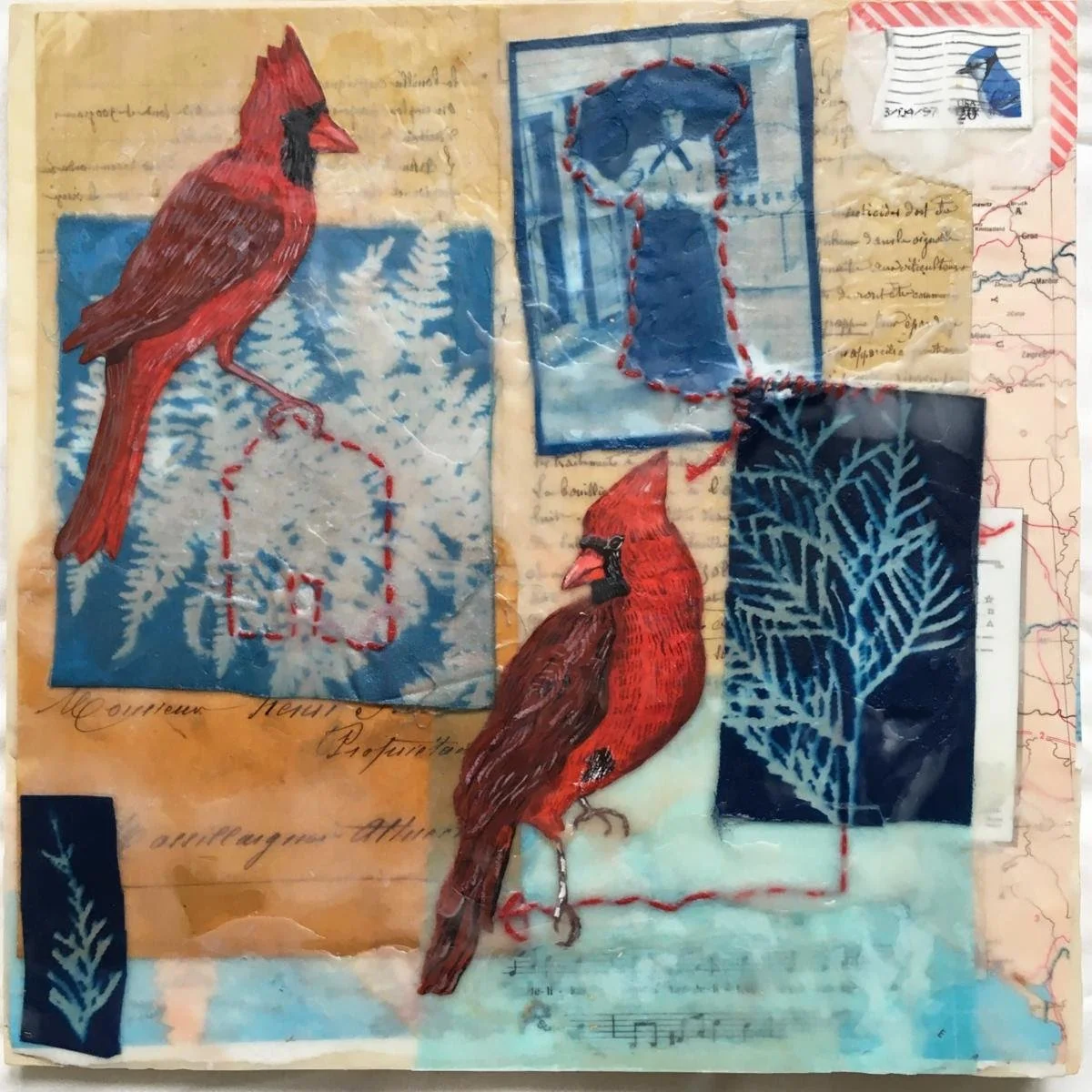

For the birds

Mixed media and encaustic, by Veronique Latimer, in the show “New Year, New Work,’’ at 6 Bridges Gallery, Maynard, Mass.

—Photo courtesy 6 Bridges Gallery

David Warsh: About the economics giant Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman in 2004.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The appearance of a long-awaited biography of Milton Friedman (1912-2006) has afforded me just the opportunity for which my column, Economic Principals (EP), has been looking. Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative (Farrar, Straus, 2023), by historian Jennifer Burns, of Stanford University, offers a chance to turn away from the disagreeable stream of daily news, in order to think a little about the characters who have populated the stage in the fifty years in which my column, EP has been following economics.

None was more central in that time than Friedman. We first met in his living room, in April, 1975, on a morning when he and his wife were packing for a week-long trip to Chile. We talked for an hour about the history of money. I left for my next appointment. Eighteen months later, Friedman was recognized with a Nobel Prize. I have followed his career ever since.

Ms. Burns’s book is a thoughtful and humane introduction to the life of an economist “who offered a philosophy of freedom that made a tremendous political impact on a liberty-loving country.” Standing little more the five feet tall, Friedman managed to influence policy, not just in the United States, but around the world: Europe, Russia, China, India, and much of Latin America.

How? Well, that’s the story, isn’t it?

Friedman grew up poor in Rahway, N.J. His father, an unsuccessful merchandise jobber, died when he was nine. His mother supported their four children with a series of small businesses, instilling in each child a strong work ethic. Ebullient and precocious, Milton was the youngest.

A scholarship to nearby Rutgers University put him in touch with economist Arthur Burns, then a 27-year-old economics instructor, forty years later Richard Nixon’s chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Burns took Friedman under his wing and pointed him toward the University of Chicago. He arrived in the autumn of 1932, as the Great Depression approached its nadir.

Ms. Burns unpacks and explains the doctrinal strife that shaped Friedman and their friends encountered there. They include Rose Director, a Reed College graduate from Portland, Ore., who, improbably in those hard times, had enrolled as a economics graduate student at the same time. The two became friends; they parted for a year, while Milton studied at Columbia University and Rose considered her options in Portland; then returned to Chicago, becoming a couple, as members of the “Room Seven Gang” in the campus’s new Social Science building. Other members included Rose’s older brother, Aaron, a future dean of the university’s law school; George Stigler, who would become Friedman’s best friend; and Allen Wallis, an important third musketeer.

Distinctly not a member of that gang of graduate students was Paul Samuelson, a prodigy who had enrolled as an undergraduate, at 16, nine months before Friedman arrived to begin his graduate studies. Already tagged by his professors as a future star, Samuelson was clearly brilliant, but impressed the Room Seven crowd as being somewhat toplofty.

All this, rich in details and explication, is but preface to the story. Ms. Burns follows the Friedmans to New Deal Washington, where they marry and work for a time; to New York, where Milton pursues a Ph.D. at Columbia and Rose drops out to start a family (neither undertaking turned out to be easy); to Madison, Wis., where the couple spent a difficult year while Friedman taught at the University of Wisconsin, before returning to wartime Manhattan, to be reunited with Stigler and Wallis, working at Columbia’s Statistical Research Group.

In 1945, the major phases of the story lay ahead: Friedman’s return to Chicago, to form a faculty group sufficiently cohesive to become recognized as a “second Chicago school,” significantly differentiated in important ways from the first; his embrace of monetary economics; his battles with other research groups seeking to shape the future of the profession. These included the Keynesians and organizational economists in Cambridge, Mass., the game theorists in Princeton, the mathematical social scientists at Stanford and RAND Corp., in California.

By 1957, Friedman had opened a political front. Lectures given at Wabash College in 1957 become a book, Capitalism and Freedom, in 1962. The book earned well, and the couple named “Capitaf,” their Vermont summer house for it. A Monetary History of the United States, with Anna Schwartz, all 860 unorthodox pages of it, appeared the same year. In 1964 Friedman was invited to become chief economic adviser to presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, much as Paul Samuelson had advised John F. Kennedy four years before,

The Bretton Woods Treaty, a hybrid gold standard arrangement negotiated in 1944, by Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, began to crumble; Friedman was ready with an alternative: flexible exchange rates determined in international currency markers. Distaste with the war in Vietnam exploded. Friedman proposed an all-volunteer army: that is, market-based wages for soldiers. Inflation grew out of control in the Seventies; Friedman had a ready answer, simply control the money supply. Just ahead are Margaret Thatcher, Paul Volcker, and Ronald Reagan. Free to Choose: A Personal Statement, by Milton and Rose Friedman, a 10-part public television series, appears in 1980, becoming an international best-seller, followed by a book.

But that is getting ahead of the story here. Ms. Burns relates all this and its surprising conclusion with grace and attention to detail. No wonder it took nine years to write! In the end it offers a seamless account. But in that very seamlessness lies a rub.

Ms. Burns is a cultural historian, concerned with rise of the American right, which in the 1950s seemed to come out of nowhere: The Road to Serfdom, by Friedrich Hayek (Chicago, 1944); Sen Joe McCarthy; the John Birch Society; God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom” (Regnery, 1951), by William F. Buckley Jr.; The Conscience of a Conservative (Victor, 1960), by Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, and the subsequent Goldwater presidential candidacy, and all that. Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (Oxford, 2009) was her previous book. She knows Friedman’s influence on economics was great – too great to cover adequately in her book. Even the subtitle raises more questions than the book itself can answer.

Therefore, as I continue to peruse Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, I intend to write over the next nine weeks about nine different books, each of which covers some aspect of Friedman’s story from a different angle. Trust me, the story is worth it: you’ll see. Meanwhile, if you get tired of reviewing the last seventy-five years, there is always the dismal news in the newspapers today.

. xxx

In a rush last week to get something into pixels about the American Economic Association meetings in San Antonio, I committed an embarrassing error.

Michael Greenstone, of the University of Chicago, delivered the AEA Distinguished Lecture, not Emmanuel Saez. You can find “The Economics of the Global Climate Challenge” here. If you care about climate warming, or simply want a glimpse of where the economics profession is headed, Mr. Greenstone’s lecture is well worth the hour it takes to watch.

That the Princeton Ph.D. and former MIT professor is today the Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor and former director of the Becker-Friedman Institute adds authority to his message.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.