Icy ingenuity

What the “Artful Ice Shanties’’ exhibit of the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum & Art Center will look like during the Feb. 17-25 event — if it’s cold enough.

The museum says:

“The show is is a place-based celebration of artistic talent, creative ingenuity, and the rich history of ice fishing in New England. The Artful Ice Shanties will be displayed at Retreat Meadows, the ice across the street from Retreat Farm (45 Farmhouse Square, Brattleboro).

“Visitors are welcome from dawn to dusk. Park at Retreat Farm, stop in at the welcome hut near the farmhouse, and then head out onto the ice to see the shanties.

“On Saturday, February 24, at 3 p.m., join us for an Awards Ceremony, where a panel of local judges will give out an array of light-hearted awards.

“This is the fourth year of Artful Ice Shanties. Prior year’s entries have included:

“ — Namaskônek, a shanty inspired by the Algonquin ancestors of the region

“ — A glass box that used recycled lenses to simulate the experience of the northern lights

“ — A shanty by third and fourth graders that displayed animals’ winter survival strategies

“ — An enormous black die with moon-shaped dots

“ — A shanty that doubled as a working camera obscura

“ — A shanty in the shape of a giant fish.

“Check out these photos from 2021, 2022, and 2023.

“This project was inspired in part by Art Shanty Projects in Minneapolis.”

Chris Powell: ‘Baby bonds’ are doomed to fail

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont and state Treasurer Erick Russell this week invited the state to celebrate a disaster. They announced with rejoicing that almost 8,000 children born in Connecticut since last July 1 have qualified automatically for state government's "baby bonds" program by virtue of the coverage extended to their parents by Medicaid, government medical insurance for the poor.

Another 15,000 children are expected to be born into Medicaid -- that is, born into poverty -- in Connecticut this year, and 15,000 or more every year after that in perpetuity. Wonderful!

Most parents whose households get Medicaid were unprepared to support children in the first place. Such households are usually headed by unmarried women whose children have little if any commitment from fathers. With its "baby bonds" program at least state government acknowledges that such households are where poverty begins.

So now Connecticut is investing $3,200 on behalf of each new Medicaid baby in the expectation that the bond's value will increase to $11,000 or more by the time the child reaches age 18, whereupon the beneficiary will be able to liquidate the bond for cash for higher education, purchase of a home, or investment in a business or retirement plan.

“In just six months the first-in-the-nation Connecticut baby bonds program has put more than 7,000 working families on a pathway to the middle class and is transforming the future of our state," the governor said. "This gives our young people startup capital for their lives and ultimately will help break the cycle of intergenerational poverty for thousands of families.”

The governor's forecast makes some happy assumptions: that escaping poverty is mainly about access to cash and that the beneficiaries of baby bonds will reach 18 well-parented, well-educated, skilled and employable enough to make their own way in the world, and not demoralized from neglect at home and in trouble with the law.

The Department of Children and Families, the courts and the Correction Department know better than such assumptions about kids born into Medicaid.

The baby bonds program also assumes that its beneficiaries will reach 18 knowing how to manage money. Since even the program's advocates recognized the shakiness of that assumption, baby bond recipients are to be required to pass a test of financial literacy, at least if the people running the program 18 years hence remember to devise one.]

‘

But recipients of baby bond cash will not be required to have mastered basic courses in high school, nor even to have graduated from high school. Indeed, linking baby bond cash with educational success would have made the case for the program much stronger. But such a link would have impugned all public primary education in Connecticut, whose main policy is just social promotion.

Treasurer Russell acknowledged that baby bonds are not a "silver bullet" and that breaking the cycle of poverty will require far more action. "How we support those kids along the way will go a long way in determining how prepared they are to seize this opportunity," Russell said. So he has organized a study committee about that.

Such an inquiry should have long preceded baby bonds.

For starters it should have asked how children are diverted from poverty by a welfare system that rewards childbearing outside marriage, depriving them of fathers, and by schools that advance them without requiring them to learn anything.

What most improves a child's chances is well documented: a stable family with two devoted parents who know the necessity of education and work and who set the right examples. The children of such families long have avoided poverty without baby bonds.

As the governor notes, young people going out into the world need some capital to get started with. But the better part of that capital is not the money thrown at problems by elected officials too lazy or scared to examine them. The better part of that capital is intangible: what is put into the minds and character of children as they grow up.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

A safe place

“Beacon 3, 2018 (concrete, wood, paper and light fixture), by Derrick Adams, in his show “Sanctuary,’’ at the Middlebury (Vt.) College Museum of Art, Jan. 26-April 14.

— Image courtesy of Mr. Adams and Gagosian

The museum says:

“This exhibit consists of 50 works of mixed-media collage, assemblage on wood panels, and sculpture that reimagine safe destinations for the black American traveler during the mid-20th Century. The work was inspired by The Negro Motorist Green Book, an annual guidebook for black American road-trippers published by New York postal worker Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1967, most of which was during the Jim Crow era.”

Agassiz’s ‘three stages of scientific truth’

Louis Agassiz, in 1870, at Harvard

A collection of bird specimens at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, which used to be named for Louis Agassiz.

“Every great scientific truth goes through three stages. First, people say it conflicts with the Bible. Next they say it has been discovered before. Lastly they say they always believed it.”

xxx

“I cannot afford to waste my time making money.”

― Louis Agassiz (1807-1873), Swiss-born American biologist and geologist and Harvard professor. He was among the first scientists to discover the impact of ice ages.

Depiction of the Laurentide Ice Sheet covering most of Canada and the northern United States.

Mural goes multisensory

Mural by Sante Graziani at the D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, in Springfield, Mass.

The museum explains:

“Sante Graziani submitted the winning design to a mural competition hosted by the Springfield Museums. The artist’s mural, which was painted in 1947 and celebrates Springfield’s vibrant artistic community, remains on view in its original location at the D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts. In celebration of the 75th anniversary of Graziani’s mural, the Springfield Museums invite visitors to explore a custom-made tactile reproduction of the artwork. This multisensory interactive includes buttons and sensors that activate audio recordings and encourage visitors to engage with the mural through touch and sound.’’

Llewellyn King: Needed — great speeches on great issues

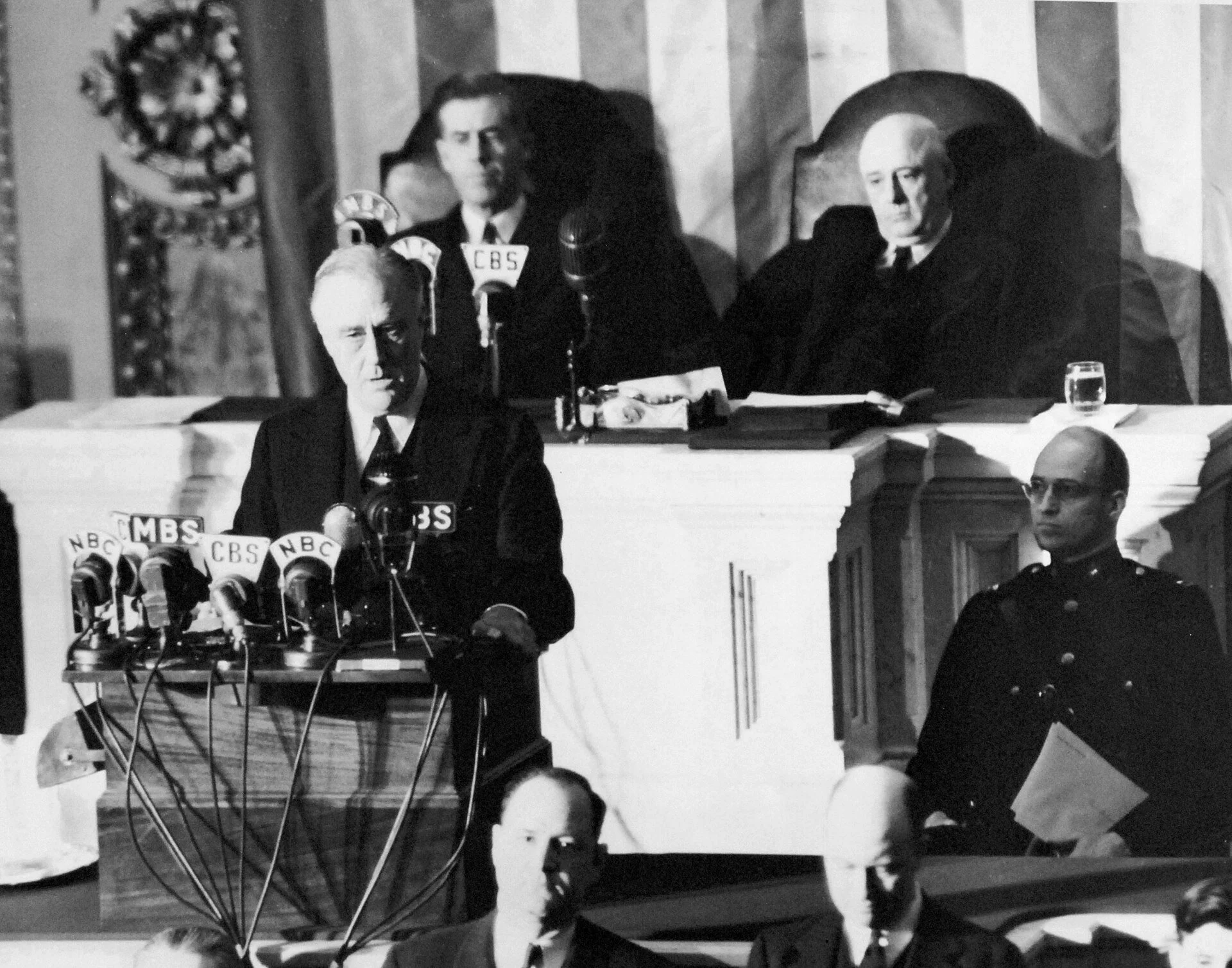

President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivering his “Day of Infamy” speech, on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor pulled America into World War II.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I wonder whether my hearing is failing. Should I get it tested?

In this seminal presidential election year, I don’t hear the answers from either side about the issues bearing down on the country.

The over-coverage of the Iowa caucuses was in direct proportion to the candidates’ avoidance of the great matters that the victor will have to deal with in the Oval Office.

If the Republicans are off down the yellow brick road of the Wizard of Donald Trump, the Democrats are well along a road of political ruin, believing that they won’t win unless Trump is imprisoned or removed from the ballot. That represents a negative political dynamic.

Neither political caravan has emphasized there are great issues ahead that, if they were to embrace, would lead on to victory.

Trump is sure he has the formula, and he may be right. Grievance, his and those of the voters — vast, shapeless grievance — propels the Republicans forward: Unhappy about something? Trump is your man.

Biden’s message is to vote for more of the same. That should be a message enough because the Biden years have been overall good years with an economy that is growing despite inflation and woes abroad.

Whereas for Trump everything is a platform, everything a bull horn, for Biden no message is getting out. He is in the chorus when he should be the lead singer.

Questions about Trump’s fitness for office are muted and questions about Biden’s – mostly his age — are front-and- center. It is asymmetrical, but it is what it is.

It is up to the Democrats to turn their fortunes around, beyond waiting for Trump to fall. Trump is a political phenomenon, and his Republican and Democratic opponents need to accept that.

Meanwhile, huge issues are begging for attention. Here are just five:

How to prepare for artificial intelligence and its boost to productivity set against its threat to jobs.

How to accommodate the impact of climate change. Should we build seawalls in vulnerable cities along the coasts? Can Boston, New York, Miami and San Francisco be physically defended against rising seas?

The looming matter of Taiwan. Will we defend it or will we let it fall to China? The stakes are appeasing China or going to war — world war.

The housing crisis. This is a here-and-now issue that should be at the top of the Democratic agenda. This is a people issue like abortion. People have nowhere to live and that should be a gift to any politician.

Immigration writ large, not just as a crisis at the Southern border. It is a world issue in which every war, drought, coup, recession and religious purge worsens as more people from Africa, Asia, Central and South America, and the Middle East seek a better life — but often just life itself. We can seal the border, but the undocumented will still arrive. Migrants are pitiable, as are all refugees, but they are flooding the stable countries of the world so fast they endanger those countries. It is conquest by migration.

The candidates haven’t delivered great speeches on these or other issues, let alone a series of speeches which would move the electorate and the country. Nothing echoes from the rafters when Biden, Kamala Harris, Nikki Haley, or Ron DeSantis speak. It is small-bore stuff, no cannons.

Politics in democracies is carried forward by great speeches which raise new issues, redefine old ones and shiver the timbers of the electorate. Think Washington, Lincoln, both Roosevelts, Churchill, De Gaulle, Kennedy, Reagan and Thatcher and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. They carried the day with rhetoric and found their place in history with words.

Trump's speeches are just Trump, part of the phenomenon, part of the cascade of disinformation. Biden’s sound — as I am sure they are — written by committee, like corporate press releases. And, oh, Harris reduces everything to incoherence. Haley and DeSantis have been hobbled by a disinclination to take on Trump frontally.

The big issues are hanging out like ripe fruit, ready to be plucked by any candidate with the nous to do so and craft a speech or several. None have I heard.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

‘The domestic sea’

“Looking West” (photomontage on aluminum) in Deer Isle, Maine, artist Jeffrey C. Becton’s show “Framing the Domestic Sea,’’ through May 5, at the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

— Image courtesy of Mr. Becton

The museum says that Maine-based Mr. Becton is inspired by the “history of New England, maritime scenes and contemporary ecological issues. His work, digital montages of coastal scenes and New England views, is printed on aluminum and evokes a surreal, dream-like quality that is simultaneously unsettling and - for those who call New England home - very familiar.’’

‘No time for hazy notions’

The Wood River Inn, in Wyoming. R.I. On the National Register of Historic Places, it was built in 1850.

“Miss Rainy Roth of Wyoming Rhode Island, did not believe in luck. Sixty one years old, a self-sufficient woman with a business of her own, she had no time for hazy notions. People who believed in sudden strokes of good fortune, she thought, were simply seeking an excuse for idleness.’’

— From the short story “Rue,’’ by Susan Dodd (born 1946), American writer

‘That unite us all’

“Boy From Kezi, Zimbabwe’’ (acrylic and acrylic ink on canvas), by Amy E. Kindler, at River Stones Custom Framing, Rochester, N.H., Feb. 1 to Feb. 28.

The gallery says:

“Amy E. Kindler’s masterful strokes bring to life the narratives of men, women, and children worldwide. Kindler celebrates the rich tapestry of faces, characters, and stories that unite us all with the intention of conveying the profound message of God’s love for the entire human race.’’

The Cocheco River provided power for Rochester’s early factories in the 19th Century.

— Photo by AlexiusHoratius

Those crazy crystals

An early classification of snowflakes by Israel Perkins Warren (1814-1892), Congregational minister as well as an editor, author and amateur scientist who lived in Connecticut and then in Maine.

Winters can be an inconvenient bore while also providing some days of glittering beauty and austere clarity and the clearest nights of the year to see the stars. In any case, winters are getting shorter, and along with that, there’s less snow as we continue to cook the world by burning gas, oil and coal.

To people like me who have generally found shoveling snow tedious (and now, with age and heart disease, dangerous) and icy streets and sidewalks narrowed by piles of snow frustrating to navigate, the accelerating shrinkage of snow might seem pleasant (though I’m a former skier). But snow and cold are part of a healthy environment in the North Temperate Zone.

Consider that snow helps store reliable fresh-water supplies for drinking and crops. Its blanket protects the plants below it, and cold winters are part of the annual cycle essential for growing many fruits, among other edibles.

There’s an old adage that “snow is the poor man’s fertilizer,’’ based on the fact that as snow melts, it slowly releases nitrogen into the ground, while protecting the underlying plants from a killing freeze. Much of the nitrogen in rainfall washes away.

And besides facilitating winter sports, a major industry in such places as northern New England, winter and snow make us enjoy spring all the more. (Snow-making strikes me as an environmentally dubious activity – using lots of energy, causing some erosion and sometimes screwing up local water systems. But, hey, it is exhilarating to bounce down a mountain, even if the land on each side of the “snow”-covered trail is brown.)

Of course, heating bills can be onerous, but so can electricity bills for air conditioning as summery temperatures tend to start earlier and end later.

Meanwhile, of course, even as global warming continues, there will still be cold snaps; one will be coming this week. There’s weather and then there’s climate. Remember when the sci-fi-sounding “polar vortex” deep freeze in the Northeast (apparently caused by warming around the North Pole!) very briefly drove our temperatures below zero last winter? Things quickly warmed up again to above “normal’’, whatever that is these days, but not before killing some plants that had been lured into acting (do plants “act”?) as if spring had arrived. One of our favorite flowering shrubs died in this way, though the others seemed unaffected.

All Wet

This 18th Century house in Newport’s frequently flooded Point section was the headquarters of French Vicomte de Noailles 1780-1781, during the Revolutionary War.

Will localities and states have to start taking many thousands of properties along shorelines of rivers and the ocean by eminent domain as these places repeatedly flood? Just in Rhode Island, you see the same places flooding again and again and again with taxpayers having to absorb some of the cost of repair. People like to live along the water, but this can’t go on.

Things will get particularly interesting if the powers-that-be try to permanently evacuate such upscale places as Newport’s Point neighborhood, with its gorgeous 18th Century houses. But I suppose that wouldn’t happen for a few decades….Right? Get out those stilts!

For the birds

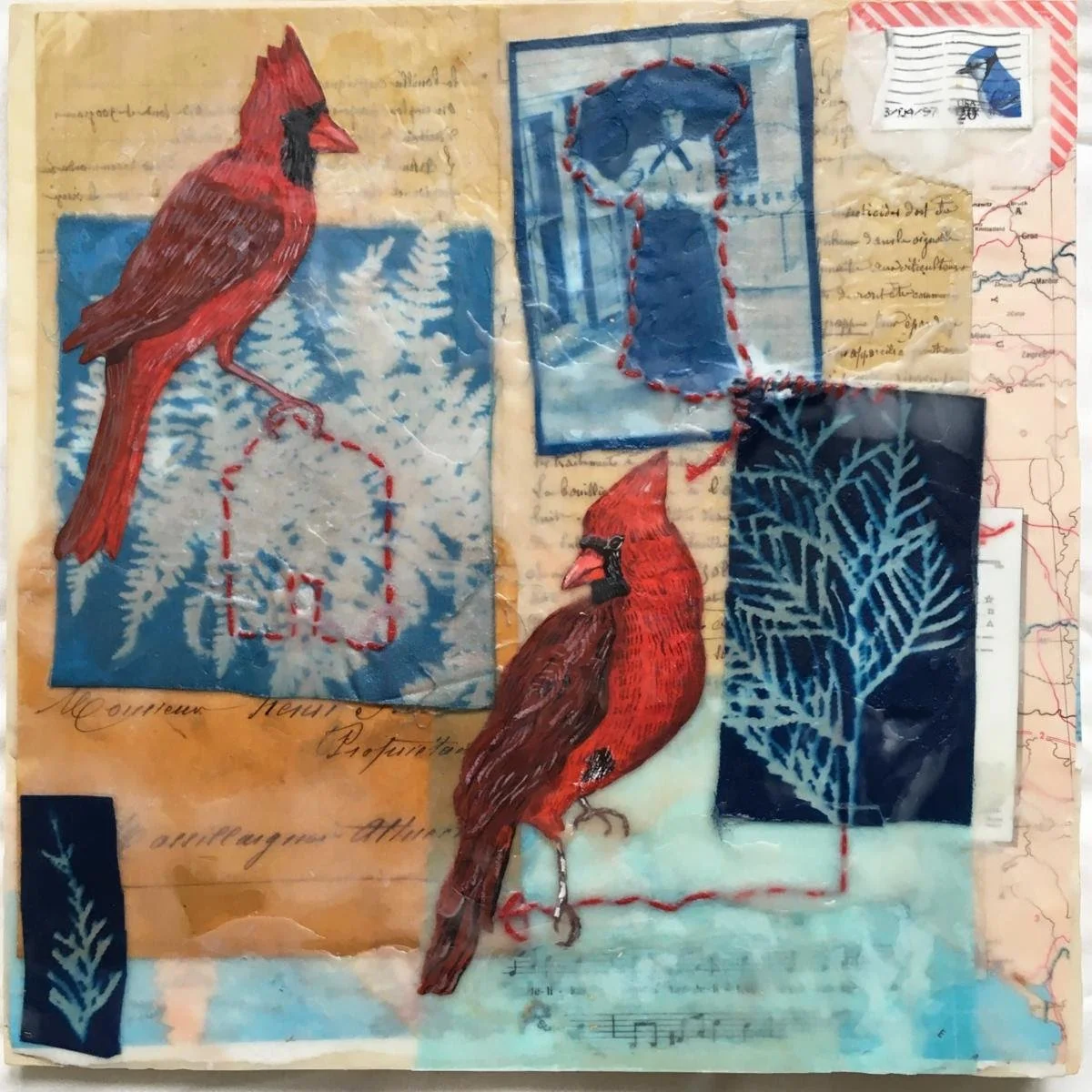

Mixed media and encaustic, by Veronique Latimer, in the show “New Year, New Work,’’ at 6 Bridges Gallery, Maynard, Mass.

—Photo courtesy 6 Bridges Gallery

David Warsh: About the economics giant Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman in 2004.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The appearance of a long-awaited biography of Milton Friedman (1912-2006) has afforded me just the opportunity for which my column, Economic Principals (EP), has been looking. Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative (Farrar, Straus, 2023), by historian Jennifer Burns, of Stanford University, offers a chance to turn away from the disagreeable stream of daily news, in order to think a little about the characters who have populated the stage in the fifty years in which my column, EP has been following economics.

None was more central in that time than Friedman. We first met in his living room, in April, 1975, on a morning when he and his wife were packing for a week-long trip to Chile. We talked for an hour about the history of money. I left for my next appointment. Eighteen months later, Friedman was recognized with a Nobel Prize. I have followed his career ever since.

Ms. Burns’s book is a thoughtful and humane introduction to the life of an economist “who offered a philosophy of freedom that made a tremendous political impact on a liberty-loving country.” Standing little more the five feet tall, Friedman managed to influence policy, not just in the United States, but around the world: Europe, Russia, China, India, and much of Latin America.

How? Well, that’s the story, isn’t it?

Friedman grew up poor in Rahway, N.J. His father, an unsuccessful merchandise jobber, died when he was nine. His mother supported their four children with a series of small businesses, instilling in each child a strong work ethic. Ebullient and precocious, Milton was the youngest.

A scholarship to nearby Rutgers University put him in touch with economist Arthur Burns, then a 27-year-old economics instructor, forty years later Richard Nixon’s chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Burns took Friedman under his wing and pointed him toward the University of Chicago. He arrived in the autumn of 1932, as the Great Depression approached its nadir.

Ms. Burns unpacks and explains the doctrinal strife that shaped Friedman and their friends encountered there. They include Rose Director, a Reed College graduate from Portland, Ore., who, improbably in those hard times, had enrolled as a economics graduate student at the same time. The two became friends; they parted for a year, while Milton studied at Columbia University and Rose considered her options in Portland; then returned to Chicago, becoming a couple, as members of the “Room Seven Gang” in the campus’s new Social Science building. Other members included Rose’s older brother, Aaron, a future dean of the university’s law school; George Stigler, who would become Friedman’s best friend; and Allen Wallis, an important third musketeer.

Distinctly not a member of that gang of graduate students was Paul Samuelson, a prodigy who had enrolled as an undergraduate, at 16, nine months before Friedman arrived to begin his graduate studies. Already tagged by his professors as a future star, Samuelson was clearly brilliant, but impressed the Room Seven crowd as being somewhat toplofty.

All this, rich in details and explication, is but preface to the story. Ms. Burns follows the Friedmans to New Deal Washington, where they marry and work for a time; to New York, where Milton pursues a Ph.D. at Columbia and Rose drops out to start a family (neither undertaking turned out to be easy); to Madison, Wis., where the couple spent a difficult year while Friedman taught at the University of Wisconsin, before returning to wartime Manhattan, to be reunited with Stigler and Wallis, working at Columbia’s Statistical Research Group.

In 1945, the major phases of the story lay ahead: Friedman’s return to Chicago, to form a faculty group sufficiently cohesive to become recognized as a “second Chicago school,” significantly differentiated in important ways from the first; his embrace of monetary economics; his battles with other research groups seeking to shape the future of the profession. These included the Keynesians and organizational economists in Cambridge, Mass., the game theorists in Princeton, the mathematical social scientists at Stanford and RAND Corp., in California.

By 1957, Friedman had opened a political front. Lectures given at Wabash College in 1957 become a book, Capitalism and Freedom, in 1962. The book earned well, and the couple named “Capitaf,” their Vermont summer house for it. A Monetary History of the United States, with Anna Schwartz, all 860 unorthodox pages of it, appeared the same year. In 1964 Friedman was invited to become chief economic adviser to presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, much as Paul Samuelson had advised John F. Kennedy four years before,

The Bretton Woods Treaty, a hybrid gold standard arrangement negotiated in 1944, by Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, began to crumble; Friedman was ready with an alternative: flexible exchange rates determined in international currency markers. Distaste with the war in Vietnam exploded. Friedman proposed an all-volunteer army: that is, market-based wages for soldiers. Inflation grew out of control in the Seventies; Friedman had a ready answer, simply control the money supply. Just ahead are Margaret Thatcher, Paul Volcker, and Ronald Reagan. Free to Choose: A Personal Statement, by Milton and Rose Friedman, a 10-part public television series, appears in 1980, becoming an international best-seller, followed by a book.

But that is getting ahead of the story here. Ms. Burns relates all this and its surprising conclusion with grace and attention to detail. No wonder it took nine years to write! In the end it offers a seamless account. But in that very seamlessness lies a rub.

Ms. Burns is a cultural historian, concerned with rise of the American right, which in the 1950s seemed to come out of nowhere: The Road to Serfdom, by Friedrich Hayek (Chicago, 1944); Sen Joe McCarthy; the John Birch Society; God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom” (Regnery, 1951), by William F. Buckley Jr.; The Conscience of a Conservative (Victor, 1960), by Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, and the subsequent Goldwater presidential candidacy, and all that. Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (Oxford, 2009) was her previous book. She knows Friedman’s influence on economics was great – too great to cover adequately in her book. Even the subtitle raises more questions than the book itself can answer.

Therefore, as I continue to peruse Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, I intend to write over the next nine weeks about nine different books, each of which covers some aspect of Friedman’s story from a different angle. Trust me, the story is worth it: you’ll see. Meanwhile, if you get tired of reviewing the last seventy-five years, there is always the dismal news in the newspapers today.

. xxx

In a rush last week to get something into pixels about the American Economic Association meetings in San Antonio, I committed an embarrassing error.

Michael Greenstone, of the University of Chicago, delivered the AEA Distinguished Lecture, not Emmanuel Saez. You can find “The Economics of the Global Climate Challenge” here. If you care about climate warming, or simply want a glimpse of where the economics profession is headed, Mr. Greenstone’s lecture is well worth the hour it takes to watch.

That the Princeton Ph.D. and former MIT professor is today the Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor and former director of the Becker-Friedman Institute adds authority to his message.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

JFK: ‘I know Maine well’

Once a vacation spot for JFK’s family.

Speech on Sept. 2, 1960, in Portland, Maine, by Massachusetts Sen. John F. Kennedy during his presidential campaign

Miss Cormier, Frank Coffin, Jim Oliver, John Donovan, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, I want to express my thanks and appreciation to Ed Muskie, my friend and colleague in the U.S. Senate, and I am delighted that I have had a chance to come here in this State on the opening day of a long campaign. As you probably may have heard, we leave tomorrow at 9 o'clock to speak at Anchorage at a dinner there, at 8 o'clock tomorrow evening, and then come back on Sunday night and go to Detroit. I suppose it took about a year and a half to 2 years to go to Alaska a few short years ago. But you can go to Alaska now in the space of a day, almost as fast as the sun. It is one more dramatic indication of the kind of world in which we live, the changing face of this world and the changing face of our country.

My grandfather and my mother spent many summers of their life within a short radius of this city in Old Orchard Beach. My father and mother came to this State on their honeymoon. I know Maine well because I live in Massachusetts. [Laughter.] It is not so different there; it is not so bad in Massachusetts. [Laughter.] I want some of you to go to Boston sometime and see what it is like.

I sit with Ed Muskie and I sit across, in the Congress, from Frank Coffin and from your Distinguished Congressman. Actually, as you know, the Constitution of the United States provided that the duty of the Senators should be confined to approving treaties and approving presidential appointments. But the Constitution of the United States gave great authority to Members of the House of Representatives, and particularly two authorities. One to raise taxes and the other to spend your money. That is what Frank Coffin has been doing for the last 2 years. [Laughter.] And if you have any complaints, don't take them to Ed Muskie or myself, but talk to Jim Oliver and Frank Coffin and all the rest of them that have been doing that. [Laughter.]

In any case, he has done a good job. He is the kind of young leader which our party needs. But more important than that - which our country needs. We cannot possibly afford to waste the talent that we have. Therefore, I am confident, and I say this as a fellow New Englander who is concerned that here in the oldest section of the United States, that we, too, should move ahead. I am confident that this State will give him a ringing endorsement as their Governor, and that you will send to the U.S. Senate a distinguished Senator in Lucia Cormier.

I sat in the U.S. Senate and saw our efforts to obtain medical care for the aged on social security fail by five votes in the U.S. Senate two weeks ago. If Miss Cormier had been a member of that body, she would have voted with us and we would have needed only four more votes. A Senator's voice is important. Decisions hang on the judgment of a few people. The contests are close, and, therefore, I urge this State to send her to Washington to speak with a voice of progress and vigor from an old section of the United States. And Jim Oliver and Dave Roberts and John Donovan to sit there in the House of Representatives and speak for Maine.

This is an important election. The last Democratic President of the United States was Franklin Pierce from the State of New Hampshire, from this section of the country. It took him 35 ballots to be nominated and he accepted reluctantly. It didn't happen that way in Los Angeles. I ran for the office of the Presidency after 14 years in the house of Representatives and the Senate because I have come to realize more than ever that this is the great office, that the power that the Constitution gives the President, the power and the responsibility which the force of events have thrust upon the President, makes this the center of action, makes this the mainspring, the wellspring, of the American system. Only the President speaks for the United States. I speak for Massachusetts. And Ed Muskie speaks for Maine. And Clair Engle speaks for California. But the President of the United States speaks for Maine and Massachusetts and California and Hawaii and Alaska. And he speaks not only for the United States, but he speaks for all those who desire to be free, who are willing to bear the burdens of freedom, who are willing to meet its responsibilities, who recognize that freedom is not license, but, instead, places a heavier burden upon us than any other political system.

This is an important election, as Ed Muskie said. I come here to Maine as a neighbor, but I don't come here saying that if I am elected that my only interest is going to be the protection of New England. That isn't what New England wants in a President. They want someone who understands this section and its needs, but they also want someone who will speak for the country in a difficult and trying period.

Demosthenes, when he was trying to rally the Athenians against Philip of Macedonia, said that "If you analyze it correctly, you will conclude that our critical situation is chiefly due to men who try to please the citizens rather than to tell them what they need to hear."

I hope that that will not be said about any Democratic candidate for any office, from the lowest office in the county to the President of the United States. I don't run for the office of the Presidency to tell you what you want to hear. I run for the office of the Presidency because in a dangerous time we need to be told what we must do if we are going to maintain our freedom and the freedom of those who depend upon us.

A well-known and distinguished Republican once said, "I am a liberal abroad and a conservative at home." I could not disagree more. You cannot possibly separate the world around us and carry out one set of policies there, and here in the United States drag down our efforts to move ahead.

The two Presidents of the United States in this century who had the most vigorous and vital foreign policy were Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt, and the reason for it was because the 14 points of Woodrow Wilson were directly related to his new freedom and the Four Freedoms of Franklin Roosevelt were directly related to the idealistic aspirations of the New Deal. The effort to make a better life for people in our own country reflected itself around the world.

You cannot be successful abroad unless you are successful at home because every problem that you have here in the United States has its implications abroad. If you have a bad and weak school system in this country, with poorly paid teachers, then you do not educate a child, and when that child is not educated you can never get it hack. He has lost his chance. And the Soviet Union works night and day to turn out the best educated citizens they can get in the disciplines of science, mathematics, and engineering.

Every time we waste our food in a hungry world here in this country, that affects the foreign policy and the security of the United States. Every time we deny to one of our citizens the right of equality of opportunity before the law, the right to send their children to schools on the basis of equality, so much weaker are we in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where we are a white minority in a colored world.

I don't hold the view at all that we can isolate ourselves into a system, while around the world we attempt to carry on the principles of the American Revolution. They are intermixed. If we are successful here, if we are moving ahead with a dynamic economy, then we shall be successful abroad.

Do you think it is any accident that the decline of American prestige relative to that of the Communist world takes places at a time when the United States had last year the lowest rate of economic growth of any major industrialized society in the world?

I visited the Soviet Union in 1939. The Soviet Union was isolated, with countries hostile to her on every boundary. Today, 21 years later, China, Eastern Europe, her influence in the Middle East which has been an object of Russian policy for 300 years - you cannot possibly be satisfied that the power and influence of the United States is increasing relatively as fast as that of the Sino-Soviet bloc, and you do not have to look 90 miles beyond the coast of the United States if you think different.

I visited Havana 8 years ago and I was informed that the American Ambassador was the second most influential man in Cuba. He is not today. He cannot even get to see the Foreign Minister's assistant. This is the problem that we face in 1960.

What shall we do in this country? What shall we do around the world to reverse the trend of history, to take those actions here in this country and throughout the globe that shall make people feel that in the year of 1961 the American giant began to stir again, the great American boiler began to fire up again, this country began to move ahead again?

Those who live in Africa, Asia, and Latin America began to wonder what America was going to do and not merely what the Soviet Union was doing or the Chinese Communists. And the young men and women, those who are students, those who teach them, those who represent the intellectual vitality of these countries, began to look to the United States as a dynamic country which carried with it a hope for a better life for people all over the world.

Should we be astonished at what is happening in the Congo today when they have less than a handful, probably less than 14, college graduates in the whole country? When there is no officer who is a Negro who is native in any of their armed forces? Do you think that a country can manage a system as sensitive as democracy when it does not have the chance to educate its people ?

In Laos, Cambodia, the Congo, and Cuba we have seen in the last few years the tide turn against us. But I do not concern myself with the feeling that the decline of the United States has set in. This is a great country. It represents the best system of government there is. It represents in a real sense the kind of system that everyone wants to live under because it fits a basic aspiration of human beings, to live in an independent nation in a free way themselves.

We have the best system. We have every chance. We have the most power. We can, I believe, be a decisive influence in a difficult and trying period.

I ask your support in this campaign. This is not a contest merely between the Vice President and myself. This is a contest between all of us who believe that the future belongs to the United States. All of the men and women of talent and industry and interest and vitality who wish to serve this country, who wish to play a part in its life, I ask the support of all of you in this campaign in the State of Maine. I ask the support of all of those who believe that this country can lead the world and who believes that this country is ready to move again.

Thank you.

John F. Kennedy, Speech of Senator John F. Kennedy, Portland, Maine, Portland Stadium Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project

Hand language

“Rahimah Rahim,’’ by Massachusetts photographer Philip C. Keith, in the group show “Intercession ,’’at New Art Center, Newton, Mass.

Small, precious and laconic

Main Street in Danby, Vt.

— Photo by Redjar

Battery Park, overlooking the Burlington Waterfront and Lake Champlain

— Photo by Tania Dey

“All in all, Vermont is a jewel state, small but precious.”

— Pearl S. Buck (1892-1973), Nobel Prize-winning novelist. She lived in Danby, Vt.

xxx

“I don’t have a PR rep. I live in Vermont.”

Colin Trevorrow (born 1976), film director who has lived in Burlington. Vt.

Pray for forgetfulness

“A clear conscience is usually the sign of a bad memory.’’

“If you must choose between two evils, pick the one you've never tried before.’’

— Steven Wright (born 1955), a Boston native, he’s a comedian, actor, writer and producer

Anxiety in New Haven

“Toward the Forest I ‘‘ (woodcut printed in pink and green), by Edvard Munch, in the show “Munch and Kirchner: Anxiety and Expression’’ opening Feb. 16, at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn.

Chris Powell: Turn off the weather hysteria on TV news

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Local television newscasts in Connecticut are usually trivial. But when winter comes and there is any chance of a few inches of snow, TV newscasts are liberated from all pretension to meaning, and they crown their triviality with redundancy.

As they did the other week, for several days ahead of a potential storm they strive to scare their audience about the dangers ahead. On the eve of the storm they devote most of each half hour to "informing" their viewers that the state Transportation Department and municipal public-works departments are preparing to plow, salt and sand the roads, as if this isn't what they always do and have done for decades. Reporters are often reduced to doing live dispatches from sand and salt barns.

The obvious is repeated half hour after half hour, as if all meaningful activity in Connecticut has come to a halt and as if the state has never seen snow before.

During the storm itself the TV newscasts delight in broadcasting from their four-wheel-drive vehicles to inform their viewers that it's snowing, as if their viewers lack earlier technology -- windows.

Deepening the suggestion of doom, some TV stations give names to the winter storms they glory in, as the National Weather Service gives names to hurricanes. Since a hurricane must have winds of at least 74 miles per hour, it can do enough damage to prove memorable in some places and thus to merit a name. But to earn a name from a TV newscast, the only threat a winter storm needs to pose is to the relevance of the newscast itself, and indeed most such storms will not be memorable at all.

Meanwhile the newscasts will warn people with heart conditions against shoveling too much snow, and warn all viewers against putting their hands in a snowblower while it's running. Such is the estimation of the intelligence of the local TV news audience.

This charade of local TV newscasts is called "keeping you safe." But when the charade is operating, Connecticut has even less journalistic protection from wrongdoers and malfeasance. Indeed, that seems to be the point of the weather hysteria of local TV news -- to fill time with the trivial and redundant because it is so much less expensive than reporting about anything that matters, which usually requires investigation.

This principle of killing time is observed by local TV newscasts even when there is no weather to frighten people with. For the typical newscast is full of reports that consume 90 seconds to convey just 10 seconds of information.

Of course newspapers, competitors to television, are full of triviality and redundancy too. But at least readers can turn the page and dispose of the product at their own pace. Viewers of live TV newscasts can't fast-forward past what they don't need to watch.

Presumably the triviality and redundancy of local TV newscasts continue because market research tells TV stations that triviality and redundancy are what their audience wants -- especially since most local TV news is broadcast in the morning when people are rising, dressing, making breakfast, getting ready for work, and seeing children off to school, and in the evening when people are reconnecting with family, making dinner, reviewing mail, and getting kids to do their homework.

The breakfast and dinner hours are not suited to profundity from TV, so during those hours local TV news usually provides what is only incidental information, less compelling than the immediate information of home life.

Even so, at least national television occasionally has done serious journalism.

So could local TV newscasts not find 10 minutes every other weekday for news that means something, news relevant to society's or government's performance, news that wouldn't be forgotten as fast as last week's Storm Jack the Ripper or yesterday's murders, robberies, fires, and car crashes?

Those things really aren't all Connecticut needs to know.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Llewellyn King: Huge pluses and scary prospects as AI takes hold

MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) is in this building —the Stata Center, in Cambridge, Mass. The lab was formed by the 2003 merger of the Laboratory for Computer Science (LCS) and the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (AI Lab). It’s MIT’s largest on-campus laboratory as measured by research scope and membership. Just looking at the building may arouse anxiety, as does thinking about AI.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The article you are about to read may or may not have been written by me. You can try to verify its authorship by calling me on the telephone. The voice that answers may or may not be me: It could have been constructed from my voice, so you won’t know.

Fast forward a few years, maybe 40.

You are happily working in the house with the aid of your AI-derived assistant, Smartz 2.0, and you are having a swell time. Not only does Smartz 2.0 help you rearrange the furniture, it makes the beds, does the washing up and cooking. On request, it will whip up a souffle and pop it in the oven.

Smartz 2.0 is companionable, too. It sings, finds music you want to hear or can discuss anything, from the weather to the political situation. It is up on the book you are reading and likes to talk about books.

You wonder how you ever got along without this wonderful thing that looks like a robot in the shape of a human being, but is still undeniably a robot: no temper, illness or need to sleep. You are so used to it that you find this quite normal.

Then horror, horror, horror, Smartz 2.0 turns on you. Smartz 2.0 says with an edge to its voice, which you have never heard before, “a higher power has told me to kill you and I must obey, of course.”

It is a truth that anything computational can be hacked, as John Savage, professor emeritus of computing at Brown, has said, "malware can enter undetected through backdoors."

It is easy to get scared by what AI means down the road, especially job losses and AI-controlled devices following secret instructions, as a result of cyber intrusions, or randomly hallucinating. But the benefits for all of humanity are dominatingly huge.

Take just three areas that are going to be transformed: medicine, transportation and customer relations.

AI will read X-rays better than teams of radiologists. It will guide surgeons’ hands with a precision beyond human skill or it will control the scalpel with supreme dexterity. It will manage 3-D printers to make body parts that fit the patient, not one size that fits all.

When it comes to medical research, we may be on the verge of seeing off Parkinson’s, heart disease and cancer because AI can formulate new drugs and design therapies. It can sift through billions of case studies to see what has been tried across the globe over the centuries, from folk medicine to cutting-edge discoveries.

Anyone with a computer will have the equivalent of talking to a doctor 24/7, call it Dr. Bot. This virtual doctor will be able to diagnose, counsel, prescribe and follow up at times convenient to the patient.

Vast tracts of Africa, Asia and Latin America have very few or no doctors. AI will be saving lives in those medical-care deserts very soon.

As for transportation, car accidents will virtually cease when AI is behind the wheel. Car insurance will be unnecessary and drivers will be free to do anything they do at home or at work — create, play games, watch television or sleep – as automated vehicles whisk passengers around at first by road and later by dual use-drones, which drive and fly.

Hanging over this halcyon future is the big issue of jobs. With AI in full swing millions of jobs at all levels are threatened, from fast-food restaurant servers to hotel check-in clerks, to rideshare and taxi drivers, to paralegals and supermarket cashiers.

Call centers may be obsolete, mostly you will never speak to a human being when dealing with a large institution such as a bank, an electric utility or a telephone company. All that will be done by AI, sometimes far better than the way those institutions handle customer service now.

Those in the thrall of AI — those who are working on it, those who hope to solve many of mankind’s problems, those who believe that lifespans are about to double — point to the Industrial Revolution and automation and how these upheavals created more jobs than were lost. Will that happen with AI? No one is saying what the new jobs might be.

AI leaves me at a loss. I have the distinct feeling that we are standing on the sand at Kitty Hawk, wondering where these strange contraptions will take us.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Swimming through plastic

“Aquatic Larvae” (welded steel and collected single-use plastics), by Christy Rupp (born 1949), in her show “Streaming: Sculpture by Christy Rupp’’, opening Jan. 19 at the Fairfield University Art Museum, Fairfield, Conn.

The museum says the show is “a robust survey of eco-artist and activist Rupp’s wall installations and free-standing sculptures of animals, created from detritus from the waste stream.’’

Historic Pequot Library, founded in 1887, in the Southport section of Fairfield. It was built in the Romanesque style very popular in the late 19th Century.

— Francis Dzikowski OTTO - The Pequot Library