That day in D.C.

“January Sixth I, 2021,” (lithograph), by Nomi Silverman,, in her show “Palpable Process,’’ at the Center for Contemporary Printmaking, in Norwalk, Conn.

The gallery says:=

“Nomi Silverman is a visual storyteller whose work elevates the voices of outsiders and those perceived as ‘other’ –people on the margins of society. She often approaches a broader story by focusing on an individual narrative, putting a human face to the generic nameless, faceless masses that are often portrayed in the media. Her subject matter has included homelessness, racial violence, Matthew Shepard, and Iraq. Most recently, she has turned her lens to topics of immigration, emigration, and refugees.

For Palpable Process, Silverman selected prints from her personal collection that will provide insight into her storytelling process, and demonstrate how she collects and creates images that will ultimately come together into a cohesive artbook or exhibit.

Norwalk Harbor and vicinity

— Photo by Joe Mabel

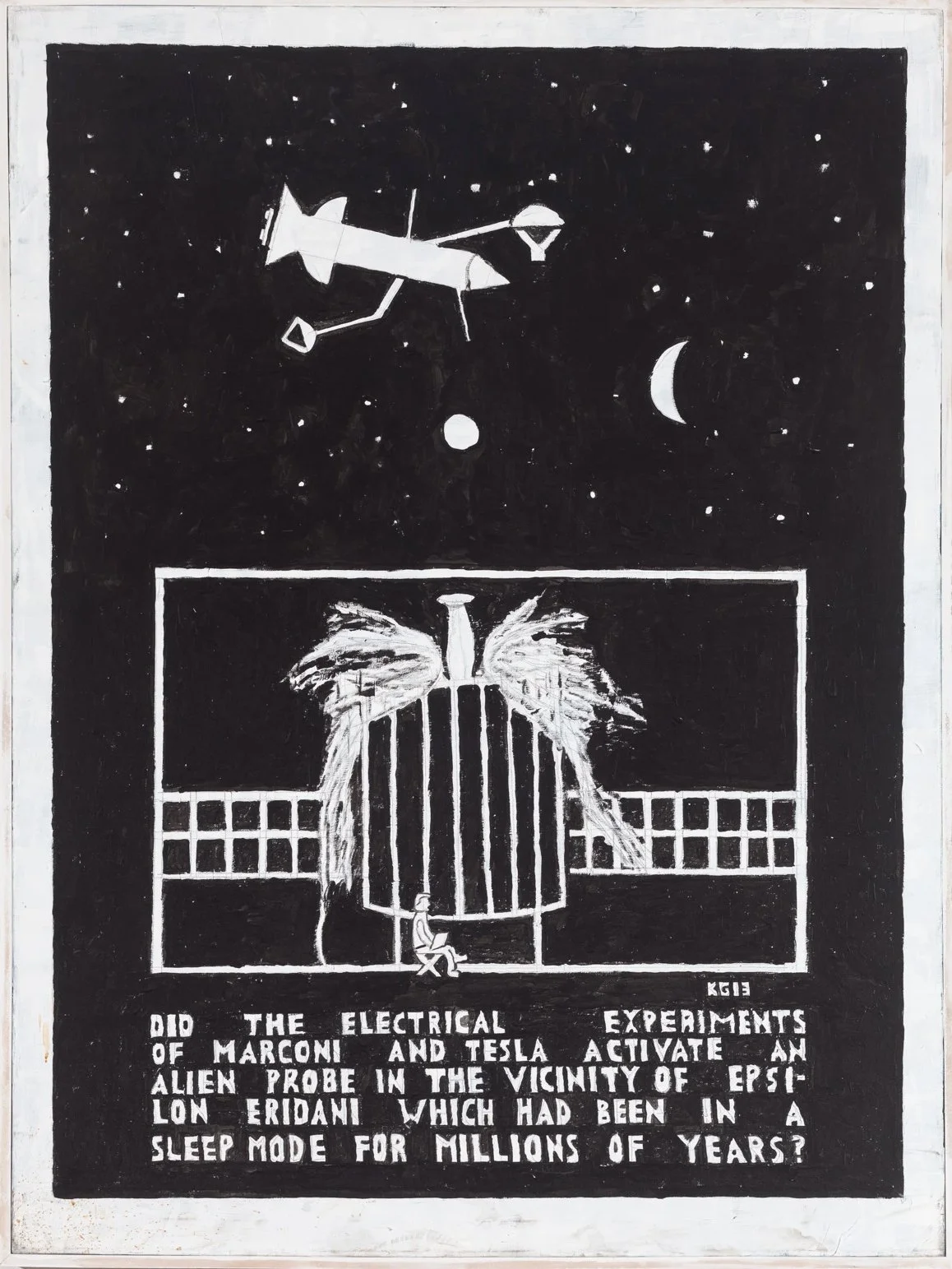

Activated an alien probe?

From the show “Ken Grimes: The Truth Is Out There,’’ at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art, New Haven, through Jan. 14.

The gallery says:

{The work of New Haven-based} Grimes {born in 1947} “focuses on the question of extraterrestrial life, a topic he has been focused on for most of his life due to a series of coincidences which he interpreted as messages from aliens. Grime’s work has primarily been black and white and so his paintings demand careful consideration yet also play with fantasy, indeed making the viewer question the possibility of life out there.’’

Chris Powell: In Connecticut and elsewhere, ‘dollar stores’ reflect poverty

— Photo by Michael Rivera

MANCHESTER, Conn

Like the rest of the country, Connecticut is seeing an explosion of "dollar stores,’’ such as Dollar General, Family Dollar and Dollar Tree, discount retailers that are causing alarm in some quarters because, while they sell food and consumer goods, they don't offer fresh meat, fruit, and vegetables and they are feared to be driving traditional food markets out of business. As a result, some municipalities around the country are legislating to restrict or even prohibit "dollar stores’’.

Now, The Hartford Courant reports, a University of Connecticut professor of agricultural and resource economics, Rigoberto A. Lopez, has published a study supporting this resentment, linking the growth of "dollar stores’’ to unhealthy diets in "food deserts" and the failure of regular grocery stores.

But "dollar stores’’ aren't doing anything illegal or immoral. They wouldn't be successful if they weren't providing goods that people want and at low prices. Nobody seems to be accusing the "dollar stores’’ of using unfair trade practices or violating anti-trust law. If "dollar stores’’ are doing better than traditional grocery stores, competition is what a free-market economy is about. People can choose where to shop.

Critics of "dollar stores’’ don't like that. They seem to think that they should be allowed to decide not just where people shop but also what they eat.

Of course there is a problem. "Food deserts" are real but retailers aren't to blame for them. Poverty is, and the expansion of "dollar stores’’ is largely a measure of worsening poverty for many in the country as a whole as well as in Connecticut.

Too many people don't eat enough fresh food quite apart from their ability to pay for it, and combine bad eating habits with poverty and the problem is worse.

But poor households qualify not just for government housing, energy and income subsidies but also for federal food subsidies -- Food Stamps are now the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program -- and if they live responsibly they can afford fresh food if they want it, and if they can travel outside their "food deserts."

That's the other part of the problem. Like other retailers, full-service supermarkets won't make as much money by locating in poor neighborhoods as they will make in middle-class and wealthy neighborhoods. By avoiding poor neighborhoods, any retailer will suffer less theft as well.

So Hartford's city government is considering opening its own supermarket. Whether city government has the competence to run anything well is always a fair question, since the poverty of so many city residents is inevitably reflected in city government itself. But there probably will be "food deserts" in cities as long as their demographics are so poor. A city government supermarket in Hartford won't solve the problem.

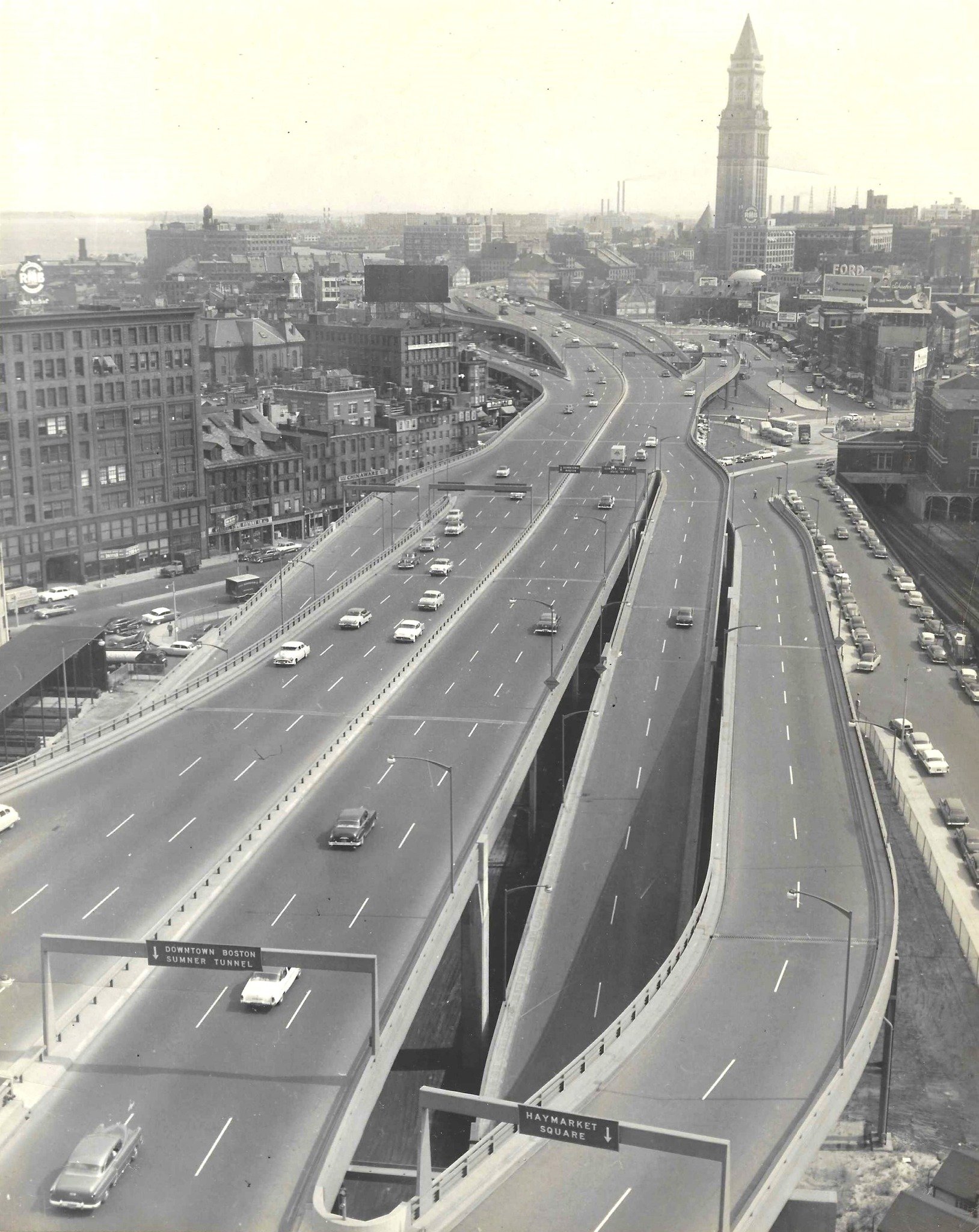

Indeed, a good measure of the long decline of Hartford from what was considered the country's most prosperous city a little more than a century ago to a struggling one is the decline in the number of chain-owned supermarkets in the city -- from 13 in 1968 to only one or two today.

Because of this poverty there isn't much retailing left in Hartford generally. For years city residents have done much if not most of their shopping in West Hartford and Manchester. West Hartford's downtown long has been far more vibrant than Hartford's, because that is where the middle and upper classes -- the people who have money to spend, people who many years ago might have lived in Hartford -- have moved.

Blaming "dollar stores” for poor nutrition among the poor is just an excuse to ignore the causes of poverty. More than a study of the impact of those stores, Connecticut could use a study of what pushed Hartford and its other cities from prosperity to privation -- such as fathers who don't father, mothers who don't parent well on their own, schools that don't educate, policies that produce dependence instead of self-sufficiency, and government that takes better care of itself than its constituents.

The decline was underway long before Ronald Reagan, Donald Trump or either of the Bushes became president. But even as the "dollar stores’’ spread across Connecticut, no one in authority seems to have any curiosity about what happened.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Downtown Hartford in 1914, during “The Insurance Capital’s’’ heyday.

‘Poetry of their corpses’

“Hark,” (pastel), by Fu’una, in the show “Måhålang (Longing)”, at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Jan. 28.

The artist says:

“There are few things more consistent in my life than a sense of longing. To be Pacific Islander on the East Coast is to feel like a part of you is always missing. In my trips to Guåhan (Guam) I’ve learned to make the most of my time. I gather images and ideas that feed my creative practice. This practice has helped me connect to wherever I am living.

“In an era where we spend 90 percent of our lives in artificial environments, I find joy in the flora and fauna that indicate where you are. But biodiversity continues to shrink as land is eaten up by condos and shopping centers. For years I would draw dead animals not just for the poetry of their corpses but for the simple fact that we are an invasive species that has disrupted once thriving habitats. I seek out what I can find and compose them in my paintings into bouquets of animals, florals, and text.

“The antidote to måhålang is presence and connection. My large-scale paintings hint at memories of immersion and claim physical space where my subjects can live in perpetuity.’’

The French connection

Percentage of the population, by county, speaking French at home in New England. This information does not discern between specific demographics of New England French, Quebec French, and dialects of immigrants from France. This does not include French Creole languages, which are spoken by a sizable population in southern New England urban centers. Percent of residents speaking French (2015) 10–15% 5–10% 1–5% 0.5-1%

Coming distractions

Above,“Winter Blues” (encaustic), by Providence-based artist Nancy Whitcomb. Below, her “Winter Blues” in oil.

How about a county revival?

Somerset County Courthouse, in Skowhegan, Maine

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

County governments with substantial powers are mostly long gone from New England. That’s for a variety of practical and political reasons. Among them are that towns and cities were incorporated here earlier than in the rest of America, and there has long been little unincorporated land (except in Maine). Still, many of the region’s counties used to have real powers (most of which were taken away in the past half century). But town and city officials have tended to want to grab those powers, and voters were increasingly convinced that counties were dinosaurs.

And yet some things are best handled regionally, rather than community-by-community, including such matters as open-space protection, water supplies and, increasingly, encouraging the provision of that somewhat ill-defined thing called “affordable housing.’’ Certainly there can be more regionalization of public-safety services and education, especially in suburban and exurban areas. This could save money (by reducing service duplication) and improve service quality.

I was impressed when I briefly worked in Delaware, in the ‘70’s, by the generally high quality of the services and infrastructure of New Castle County, which includes the city of Wilmington as well as suburban and exurban land. It’s one of three counties in The First State, which is the second smallest state in the Union by area. New Castle County has an elected county council and county executive. Rhode Island, especially, would do well to study it. As has been asked many times before, does the tiny Ocean State really need 39 municipalities and 36 school districts (32 municipal and 4 regional) school districts? But maybe the desire for very local control trumps efficiency?

Mixed traffic

“Ciiserec —Now Do You See It?” (collage and mixed media on ledger paper), by Henry Payer, in the show “Free Association: New Acquisitions in Context,’’ at the Addison Gallery of American Art, in Andover, Mass.

The gallery says:

{The show} “places a focus on the gallery's newest additions to its collection. But new works don't exist in a vacuum, each piece is surrounded by other works collected over the Addison's nearly 100-year history. These associations create a dialogue between old and new, putting everything in a new light.’’

Samuel Phillips Hall, the social science and language building of Phillips Academy, the elite boarding school in Andover.

'And paying for the sins of their parents'

“When I grew up, there really was the sense of ’Why would you want to live anywhere else?’ {than the Boston area} .There’s a proudly parochial aspect to Boston. That strong tug of place was one of the themes I wanted to work with, the way environment influences what somebody becomes, that and children paying for the sins of their parents.”

— Ben Affleck (born 1972), American movie actor, director and producer. Born in Berkeley, Calif., he grew up in Cambridge, Mass.

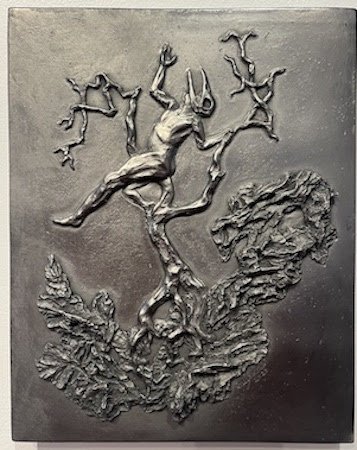

My ‘stark vulnerabilty’

Work by Andy Moerlein at Boston Sculptors Gallery. He’s based in Maynard, Mass.

He says:

“Men are always expected to be ‘Age Defying Superheros.’

”As I add years to my very physical life, I am finding my limitations creeping inward ever so slowly. As a sculptor of large work, my pieces demand a wearing and persistent physicality. In my art I confront ideas and challenge different media – using my stamina and strength, my mind and memories.

”As I contemplate the endless and seemingly pointless things I do as an artist – as I meander around and try to process what I am experiencing. As I work to understand myself in relationship with the greater world around me, it seems the goal posts are always moving. A toil without end. Yet I relish the work. Perhaps as much as my results. It is a joy to work with my hands and mind every day.

”As maturity becomes evident, and those about me age and die, I am confronting a stark vulnerability that I have lived my life rather oblivious to.

“Frankly, at the start of this exploration, I struggled with my own modesty. I drew in masks and settled on clay reliefs as a medium. As I needed better renderings, I shot self-portraits. When I needed impossible positions, I collaged photocopies together. Through the hours of work, I became immune to my self exposure. My collages became more than references and I recognized them as works on their own.’’

Maynard in 1879, at the height of the Industrial Revolution.

But you get used to it

“Cold Morning” (1951), by Francis P. Colburn (1909-1984) at the Fleming Museum of Art, at the University of Vermont, in Burlington. He was a native of Fairfax, Vt.

A house in Fairfax during winter

— Photo by Doug Kerr

James T. Brett: A plea for ‘civilizing speech’ in 2024

Regions of New England 1. Northwest Vermont 2. Northeast Kingdom 3. Central Vermont 4. Southern Vermont 5. Great North Woods Region 6. White Mountains 7. Lakes Region 8. Dartmouth/Lake Sunapee Region 9. Seacoast Region 10. Merrimack River Valley 11. Monadnock Region 12. North Woods 13. Maine Highlands 14. Acadia/Down East 15. Mid-Coast/Penobscot Bay 16. South Coast 17. Mountain and Lakes Region 18. Kennebec Valley 19. North Shore 20. Metro Boston 21. South Shore 22. Cape Cod and Islands 23. South Coast 24. Southeastern Massachusetts 25. Blackstone River Valley 26. Metrowest/Greater Boston 27. Central Massachusetts 28. Pioneer Valley 29. The Berkshires 30. South Country 31. East Bay and Newport 32. Quiet Corner 33. Greater Hartford 34. Central Naugatuck Valley 35. Northwest Hills 36. Southeastern Connecticut/Greater New London 37. Western Connecticut 38. Connecticut Shoreline

At the close of 2023, a pollster quipped that the state of our union resembled “mourning in America”… a sober sentiment about a turbulent year filled with relentless challenges and grievous perils as close as debates and disputes in our local communities… and as far away and yet as inextricably linked as the ongoing tragic upheavals in distant lands.

I would never turn my back on the past -- as we turn the pages of the calendar year -- for our past will always define, inform, and determine our future … the future that we will to need to face and address with renewed conviction, but also with a resolve that seeks to both break down walls and unwind the dispiriting display of uncivil discourse.

But the present moment – this new year – offers us an opportunity to start anew, to amend, to actually “look with eyes that see”. To soften the heart…to sharpen both the mind and the pencil, and to fix what is broken. To work to deepen the dialogue, to dial back the divisive rhetoric, to break down the walls of “us” and “them”.

What “we the people” need is civilizing speech for that is what makes us most human. What makes us most civil begins with respectful, open-minded listening – in our places of both labor and leisure. Offering our better selves… our “better angels” … in thoughtful and thought-filled communities where attentive deliberations can help us clarify what is important to us as moral beings as we renavigate our very differences. I know the tasks at-hand are many…and complex, often difficult, but vitally important. I know too that my and our efforts won’t always succeed, but I also know we cannot stand aside.

For all my years invested in such fine company kept at the New England Council, within the charitable organizations of our states, with our legislative bodies, and powerfully and poignantly for me in my faith community, I have received such bountiful blessings, made such special friends, and have had my belief that we are “stronger together” affirmed many times over. The work of the spirit and the will of good citizens can come together to produce revelatory miracles and great surprises.

On into the new year with renewed hope and optimism.

James T. Brett is president and chief executive of The New England Council, based in Boston.

The unofficial flag of New England.

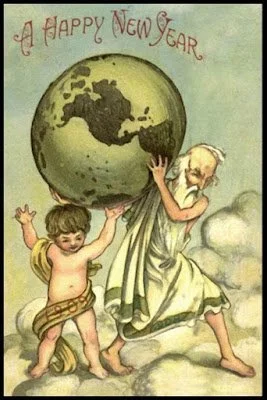

‘The burden of a year'

“Father Time and Baby,’’ 1909

What can be said in New Year rhymes,

That’s not been said a thousand times?

The new years come, the old years go,

We know we dream, we dream we know.

We rise up laughing with the light,

We lie down weeping with the night.

We hug the world until it stings,

We curse it then and sigh for wings.

We live, we love, we woo, we wed,

We wreathe our prides, we sheet our dead.

We laugh, we weep, we hope, we fear,

And that’s the burden of a year.

‘‘The Year,’’ by Ella Wheeler Wilcox (1850-1919). She spent much of her adult years living in Branford, Conn.

Branford Town Hall

— Photo by Kenneth Zirkel

Mountain marvels

The late lamented gondolas at Wildcat Mountain, in New Hampshire. Working from 1958-1998, they were the first ski area gondolas in the United States. They were replaced by a high-speed chair-lift system.

“Mount Lafayette in Winter” (1870), by Thomas Hill (1829-1908). The mountain, at 5,249 feet, is the highest peak in New Hampshire’s Franconia Range.

Thin religiosity and archaic roads

On a typically narrow Boston road — Hull Street. From left to right: the Skinny House, the Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge and the Copp's Hill Burying Ground. The Skinny House, built soon after the Civil War, is reportedly the most narrow in Boston, and is said to have been built to spite the neighbors.

“Even after thirty years, I still think New Englanders sound funny, that they expect too much of the Red Sox, that their religiosity is more procedural than deeply felt, and that their highways are built with the conviction that automobiles could not possibly replace the horse-drawn buggy, and therefore need not be wide, permanent, or especially well-designed.’’

-- C. Michael Curtis (1934-2023) in New England Stories (1992). A New York City native, he was the long-time fiction editor of The Atlantic (magazine ), which was based in Boston from its founding, in 1857, until it was moved to Washington, D.C., in 2006

First Unitarian Church of Providence.

‘Light, space and poetry’

“Quarry Winter” (oil on linen), by Thomas Torak, at Helmholz Fine Art, Manchester, Vt.

He says:

“Luminosity, atmosphere, poetry, craftsmanship, joy, life. These are the cast of characters in my paintings. Most artists use light, color and design to express what they want to say about the objects in their paintings, I do just the opposite in my work. I use subject matter, apples, flowers, trees, mountains, portraits and nudes to explore the possibilities of light and space and poetry. Some artists paint in prose, some paint in poetry. There are artists who feel the more details they paint, the more accurately they describe something, the more successful their painting will be. Others, like myself, prefer to express things in the most elegant way possible.’’

Marble quarry in Dorset, Vt.

Woodbury Granite Co, around 1900.

Rock of Ages granite quarry in Graniteville, Vt.

— Photo by Mfwills

Chris Powell: Criminal convictions shouldn’t be a secret

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut law is full of mistaken premises, and more will be added in January when the criminal records of an estimated 80,000 people will be privatized -- not exactly erased but removed from public access under what is being called the “clean slate” law. The records involve convictions for misdemeanors more than seven years old and "low-level" felonies more than 10 years old committed by people not convicted of anything since.

The rationale for the new law is, first, that it's not fair that old convictions should be known, and, second, that public knowledge of convictions is a huge impediment to people seeking housing and employment.

But why shouldn't convictions be impediments to getting housing and jobs?

Since most criminal charges are substantially discounted in plea bargaining to avoid trials, most people who have been convicted have already received extra consideration from the government. So what is fair about eliminating all trace of their discounted offenses?

What is fair about depriving landlords and employers of basic information about people for whom they may become responsible?

What is fair about keeping people ignorant of what their government has done?

Of course, society also has an interest in having everyone honestly employed. But people have to compete for jobs and housing, so why shouldn't people who have not committed crimes have an advantage over former offenders? Why shouldn't former offenders have to try harder to show they are worthy of trust?

Criminal convictions are not the biggest impediment to finding housing these days. The biggest impediment is the sharply rising price of housing that results from general inflation and the general scarcity worsened by municipal zoning. Connecticut is said to need at least 90,000 more housing units for its current population. If the state suddenly had another 390,000 units, rents would be much lower and landlords wouldn't be so picky about tenants. Eliminating public access to conviction records will not build more housing.

Criminal convictions are probably not the biggest impediment to obtaining jobs either.

Gov. Ned Lamont himself hinted as much this month when he announced that the "clean slate" law would take effect in January. The governor noted that Connecticut has a labor shortage and "desperately" needs former offenders in the workforce. The worse the shortage of labor, the more that employers will be willing to overlook old convictions, if former offenders can demonstrate their ability to do the job -- and ability to do the job is almost certainly the biggest impediment to employment for former offenders.

Lack of a good upbringing, education, and job skills push people toward crime, and Connecticut, with a welfare system based on destroying families and a school system based on social promotion, is full of people who lack what they need to support themselves. Indeed, if one's education and job skills are strong enough, even the worst offenses may be readily forgiven.

Such is the lesson of the rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, the first hero of the United States space program.

Von Braun's career during World War II was with the Nazi government of Germany. He designed the infamous V-2 rocket bomb, became a major in the criminal SS military force, and was awarded the Iron Cross by Adolf Hitler himself. (Years later a biography of von Braun was titled "I Aim at the Stars," prompting the American comedian Mort Sahl to say it should have been subtitled "But I Sometimes Hit London.")

Nevertheless the U.S. government hired von Braun as soon as the war ended. His rocketry skills overcame any concern about his record as a Nazi criminal mastermind.

Instead of presuming that erasing criminal records will somehow qualify people for housing and jobs, state government should provide a year or so of paid employment, basic medical insurance, and rudimentary housing for former offenders who are not yet able to support themselves, allowing them to build the creditable record everyone needs to gain employment and housing.

Better still, state government should fix the failures of its welfare and education systems.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years. (CPowell@cox.net).\

Llewellyn King: My Christmas in poor, beautiful Cuba

These Spanish Colonial era buildings are a common sight across Havana, along with old cars.

— Photo by Bryan Ledgar

There was much business done in Cuba by New England enterprises, especially in sugar but also in tobacco and fruit. Here’s the Soledad plantation of Belmont, Mass.-based sugar mogul Edward F. Atkins. In the late 19th Century, Atkins was a dominant force in the U.S.-Cuban sugar market. His firm, E. Atkins & Co., established sugarcane plantations along the southern coast of Cuba near the cities of Cienfuegos and Trinidad. From the 1840s through the 1920s, the Atkins family operated their sugar business on the island, seeing it through the abolition of slavery, Cuba's fight for independence from Spain, and the changing agricultural and industrial practices of sugar production.

The huge and Boston-based United Fruit Co. owned or leased many properties in Cuba.

I have had a hankering to go back to Cuba. I went there with other journalists on a trip organized by the Center for Strategic and International Studies in the 1980s; and again on a National Press Club trip in 2003.

Over Christmas I went back, just to Havana, that dowager city, and lost myself in the best of Cuba: its architecture, its food, its music and its people.

But around me were plenty of signs of the other Cuba, the Cuba which is in extremis — the Cuba which is driving its citizens to leave in record numbers.

In 2022, by some accounts, about 400,000 Cubans left for work and a new life wherever in the world they could find it. The Customs and Border Protection agency estimates that in a recent two-year period, 425,000 sought entry to the United States.

Many Americans are surprised to hear that you can travel easily to Cuba these days. The confusion arises as the law seems to say “no,” but the regulations posted by the Treasury Department say “yes.”

My wife and I went through a commercial Cuba travel service called Cuba Explorer. We didn’t want to go as journalists; we wanted to take a quiet look at Havana, not through the eyes of officialdom. We signed up and so did two friends, a retired doctor and his wife.

The tour company arranged our Cuban visa and the “Certificate of Legal Cuba Travel,” a U.S. requirement. All we did was buy our tickets on American Airlines, which operates daily service from Miami. Delta, Southwest and JetBlue and also fly to Havana from various cities.

Border formalities are no more difficult than they are going to any country — say, Mexico or the United Kingdom.

Havana — and some of the smaller colonial towns which I visited previously — is a delight. It is among the great “built cities” of the world, like Paris, Vienna and St. Petersburg. However, as Havana is compact, it is easily seen; it is the kind of place you feel you can get your arms around.

The grandeur of its colonial past, its wealth of another time, is everywhere. So is the poverty of today. Some streets are sad, indeed, with all the manifestations of poor countries: people picking over garbage, pedal carts, even bullock carts. There are few overweight people and while Cuban food is complex and sophisticated, I’m told that Cubans survive on rice and beans.

Cubans also queue. Jokingly, one Cuban told me, “When we see a line, we go and stand in it — must be something good and, like all good things here, in short supply.”

Food for those outside the dollar-driven tourist economy is a struggle, as are medicines and simple things, like a favorite shampoo or paper products of all kinds. For travelers, one of the pleasures of Havana is that you always get a cloth napkin, not of choice but of necessity. Our new, comfortable hotel ran out of toilet paper. The American obsession with carrying Kleenex came in handy.

The 1950s cars are as plentiful as ever, but many are reengineered with modern Japanese or Russian engines; some declare they are all original parts and use Cubans abroad to scavenge junk yards and send parts back in relatives’ luggage.

The sanctions, with small modifications, have lasted since 1962, and are the longest-ever in U.S. history — and they haven’t worked. They haven’t brought down the Communist Party, freed the press or made the life of Cubans any better. Instead, they have subtracted hope.

The embargo is a peculiar cross that Cuba alone bears, especially when you think of the many dictatorial regimes we tolerate and befriend.

The Hill reported that Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador told President Biden in a phone call that he could help reduce migration in the region if he could loosen the sanctions on Cuba. It is hard to find a Cuban who wants to leave the island, but wouldn’t if he or she could.

After 20 years, I had hoped to find a more prosperous Cuba, but it hasn’t happened. The small areas of free enterprise allowed by the state have created little oligarchies. Taxi drivers and waiters make much more money than doctors and engineers. These professionals count among Cuba’s exports, its brain drain. On the upside, there are many private restaurants with a thriving food culture for those who can afford it.

The fault is the failed Cuban communist model, but the United States hasn’t helped. Graham Greene, the great British writer, who penned The Power and the Glory, about the Mexican Revolution — from 1910 to 1920 —pointed out that it failed without the aid of an American embargo.

I have felt, now for 40 years, that Cuba would throw off communism if we let it alone, and got rid of the embargo, which is more about U.S. politics than the politics of Cuba.

Meanwhile, do visit Cuba while you can. It is a treat for the eyes, the ears and the palate. You won’t regret it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Take the Little Circle Route

The westbound I-195 entrance ramp in East Providence was closed due to the Washington Bridge closure.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The economic and psychological damage from the ongoing Washington Bridge repair job will, it seems, last for months. I had thought that perhaps the traffic mess would have been smoothed out a lot within a few days. But on Dec. 20, in clear weather and not during commuting hours -- we saw a traffic jam extended for miles on Route 195 West as we headed on the highway’s eastbound side, which we got to via a confusing and circuitous route in always-problematical East Providence. Clearer signage, please! We were bogged down for quite a while on Broadway in that speed-trap-rich city, with its ingeniously confusing signs. Pretty tough to speed there now, not that you should!

So we decided to return to Providence from our meeting in Dartmouth, Mass., via 195 West and then 24 North to 495 North from which we got on 95 South. The trip took a little over an hour and a half. The detour was well worth it. Drivers should avoid 195 anywhere near Providence, especially those with heart or other serious health issues. You’d find it hard to be rescued in a miles-long traffic jam. And you might run out of gas