Newport and China

At “The Celestial City: Newport and China” show at Rosecliff mansion, Newport through Feb. 11, except Nov. 16-Dec. 3.

The Preservation Society of Newport County (whose show it is), explains that the show:

“{E} explores China’s deep influence on Newport from the 18th century through the Gilded Age, when the city emerged as America’s premier summer playground and the fall of China’s last imperial dynasty transformed the ancient nation. The extraordinary objects displayed include more than 100 works in a range of media, from paintings, ceramics, and photographs to fashion, lacquerwares, and lanterns. Contemporary artworks by Yu-Wen Wu and Jennifer Ling Datchuk illuminate Chinese contributions to Newport as well as hidden connections between the Newport mansions and the Chinese-American experience.’’

Michelle Andrews: Primary-care physicians feel underpaid

From Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Health News

“You have to really want to be a primary-care physician when that student will make one-third of what students going into dermatology will make.’’

— Russ Phillips, M.D., internist and director of the Harvard Medical School Center for Primary Care, in Boston

Money talks.

The United States faces a serious shortage of primary-care physicians for many reasons, but one, in particular, is inescapable: compensation.

Substantial disparities between what primary-care physicians earn relative to such specialists as orthopedists and cardiologists can weigh into medical students’ decisions about which field to choose. Plus, the system that Medicare and other health plans use to pay doctors generally places more value on doing procedures such as replacing a knee or inserting a stent than on delivering the whole-person, long-term health-care management that primary-care physicians provide.

As a result of those pay disparities, and the punishing workload typically faced by primary-care physicians, more new doctors are becoming specialists, often leaving patients with fewer choices for primary care.

“There is a public out there that is dissatisfied with the lack of access to a routine source of care,” said Christopher Koller, president of the Milbank Memorial Fund, a foundation that focuses on improving population health and health equity. “That’s not going to be addressed until we pay for it.”

Primary care is the foundation of our health-care system, the only area in which providing more services — such as childhood vaccines and regular blood pressure screenings — is linked to better population health and more equitable outcomes, according to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, in a recently published report on how to rebuild primary care. Without it, the national academies wrote, “minor health problems can spiral into chronic disease,” with poor disease management, emergency-room overuse, and unsustainable costs. Yet for decades, the United States has underinvested in primary care. It accounted for less than 5 percent of health care spending in 2020 — significantly less than the average spending by countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, according to the report.

A $26 billion piece of bipartisan legislation proposed last month by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, and Sen. Roger Marshall (R-Kan.) would bolster primary care by increasing training opportunities for doctors and nurses and expanding access to community health centers. Policy experts say the bill would provide important support, but it’s not enough. It doesn’t touch compensation.

“We need primary care to be paid differently and to be paid more, and that starts with Medicare,” Koller said.

How Medicare Drives Payment

Medicare, which covers 65 million people who are 65 and older or who have certain long-term disabilities, finances more than a fifth of all health-care spending — giving it significant muscle in the health-care market. Private health plans typically base their payment amounts on the Medicare system, so what Medicare pays is crucial.

Under the Medicare payment system, the amount the program pays for a medical service is determined by three geographically weighted components: a physician’s work, including time and intensity; the practice’s expense, such as overhead and equipment; and professional insurance. It tends to reward specialties that emphasize procedures, such as repairing a hernia or removing a tumor, more than primary care, where the focus is on talking with patients, answering questions, and educating them about managing their chronic conditions.

Medical students may not be familiar with the particulars of how the payment system works, but their clinical training exposes them to a punishing workload and burnout that is contributing to the shortage of primary care physicians, projected to reach up to 48,000 by 2034, according to estimates from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The earnings differential between primary care and other specialists is also not lost on them. Average annual compensation for doctors who focus on primary care — family medicine, internists and pediatricians — ranges from an average of about $250,000 to $275,000, according to Medscape’s annual physician compensation report. Many specialists make more than twice as much: Plastic surgeons top the compensation list at $619,000 annually, followed by orthopedists ($573,000) and cardiologists ($507,000).

“I think the major issues in terms of the primary-care physician pipeline are the compensation and the work of primary care,” said Russ Phillips, an internist and the director of the Harvard Medical School Center for Primary Care. “You have to really want to be a primary-care physician when that student will make one-third of what students going into dermatology will make,” he said.

According to statistics from the National Resident Matching Program, which tracks the number of residency slots available for graduating medical students and the number of slots filled, 89 percent of 5,088 family medicine residency slots were filled in 2023, compared with a 93 percent residency fill rate overall. Internists had a higher fill rate, 96 percent, but a significant proportion of internal medicine residents eventually practice in a specialty area rather than in primary care.

No one would claim that doctors are poorly paid, but with the average medical student graduating with just over $200,000 in medical school debt, making a good salary matters.

Still, it’s a misperception that student debt always drives the decision whether to go into primary care, said Len Marquez, senior director of government relations and legislative advocacy at the Association of American Medical Colleges.

For Anitza Quintero, 24, a second-year medical student at the Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine in rural Pennsylvania, primary care is a logical extension of her interest in helping children and immigrants. Quintero’s family came to the United States on a raft from Cuba before she was born. She plans to focus on internal medicine and pediatrics.

“I want to keep going to help my family and other families,” she said. “There’s obviously something attractive about having a specialty and a high pay grade,” Quintero said. Still, she wants to work “where the whole body is involved,” she said, adding that long-term doctor-patient relationships are “also attractive.”

Quintero is part of the Abigail Geisinger Scholars Program, which aims to recruit primary-care physicians and psychiatrists to the rural health system in part with a promise of medical school loan forgiveness. Health care shortages tend to be more acute in rural areas.

These students’ education costs are covered, and they receive a $2,000 monthly stipend. They can do their residency elsewhere, but upon completing it they return to Geisinger for a primary-care job with the health care system. Every year of work there erases one year of the debt covered by their award. If they don’t take a job with the health-care system, they must repay the amount they received.

Payment Imbalances a Source of Tension

In recent years, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which administers the Medicare program, has made changes to address some of the payment imbalances between primary care and specialist services. The agency has expanded the office visit services for which providers can bill to manage their patients, including adding non-procedural billing codes for providing transitional care, chronic care management, and advance care planning.

In next year’s final physician fee schedule, the agency plans to allow another new code to take effect, G2211. It would let physicians bill for complex patient evaluation and management services. Any physician could use the code, but it is expected that primary-care physicians would use it more frequently than specialists. Congress has delayed implementation of the code since 2021.

The new code is a tiny piece of overall payment reform, “but it is critically important, and it is our top priority on the Hill right now,” said Shari Erickson, chief advocacy officer for the American College of Physicians.

It also triggered a tussle that highlights ongoing tension in Medicare physician payment rules.

The American College of Surgeons and 18 other specialty groups published a statement describing the new code as “unnecessary.” They oppose its implementation because it would primarily benefit primary care providers who, they say, already have the flexibility to bill more for more complex visits.

But the real issue is that, under federal law, changes to Medicare physician payments must preserve budget neutrality, a zero-sum arrangement in which payment increases for primary-care providers mean payment decreases elsewhere.

“If they want to keep it, they need to pay for it,” said Christian Shalgian, director of the division of advocacy and health policy for the American College of Surgeons, noting that his organization will continue to oppose implementation otherwise.

Still, there’s general agreement that strengthening the primary-care system through payment reform won’t be accomplished by tinkering with billing codes.

The current fee-for-service system doesn’t fully accommodate the time and effort primary-care physicians put into “small-ticket” activities like emails and phone calls, reviews of lab results, and consultation reports. A better arrangement, they say, would be to pay primary care physicians a set monthly amount per patient to provide all their care, a system called capitation.

“We’re much better off paying on a per capita basis, get that monthly payment paid in advance plus some extra amount for other things,” said Paul Ginsburg, a senior fellow at the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics and former commissioner of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

But if adding a single five-character code to Medicare’s payment rules has proved challenging, imagine the heavy lift involved in overhauling the program’s entire physician payment system. MedPAC and the national academies, both of which provide advice to Congress, have weighed in on the broad outlines of what such a transformation might look like. And there are targeted efforts in Congress: for instance, a bill that would add an annual inflation update to Medicare physician payments and a proposal to address budget neutrality. But it’s unclear whether lawmakers have strong interest in taking action.

“The fact that Medicare has been squeezing physician payment rates for two decades is making reforming their structure more difficult,” said Ginsburg. “The losers are more sensitive to reductions in the rates for the procedures they do.”

Michelle Andrews is a KFF Health News reporter.

Michelle Andrews: andrews.khn@gmail.com

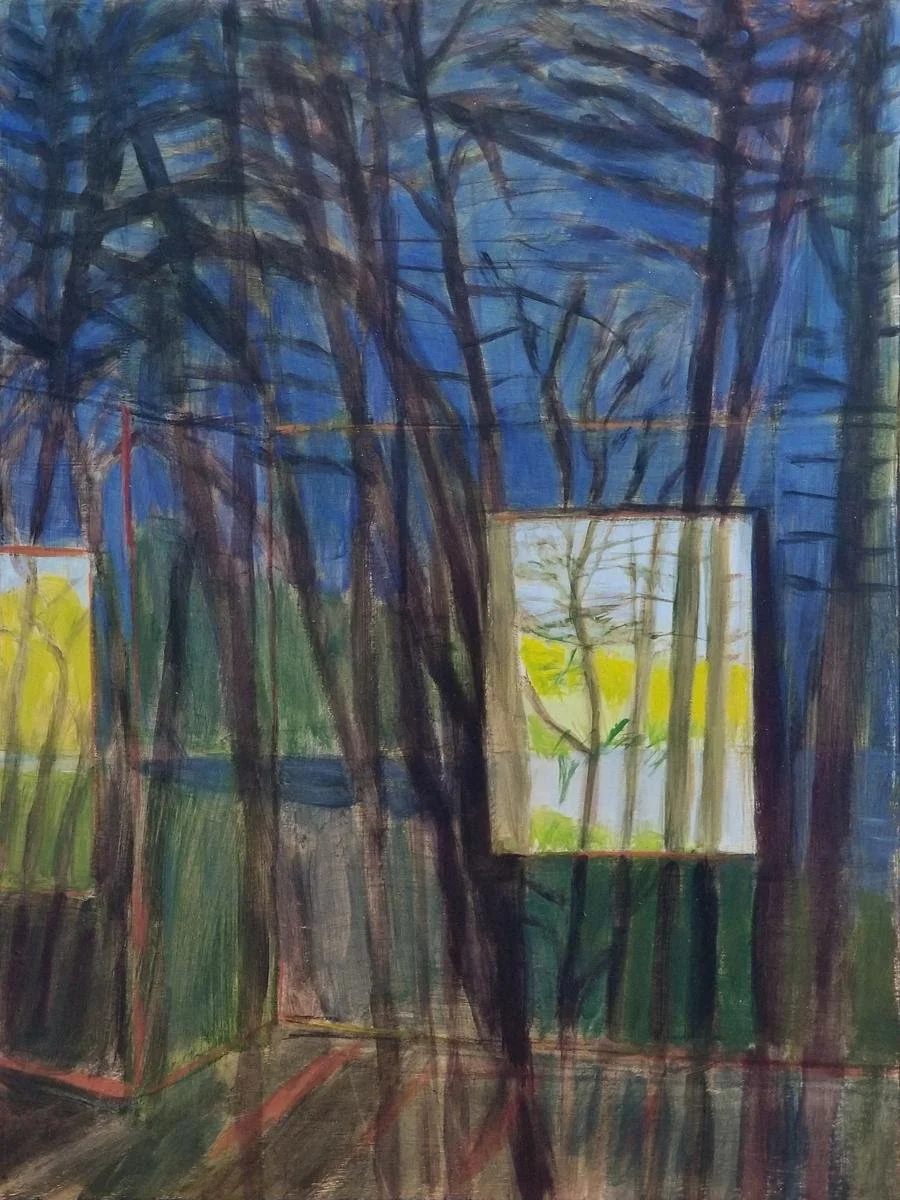

The trees that remain

‘‘Outside In” (acrylic on panel), by Concord, Mass.-based artist Irene Stapleford, in her show “Sightlines,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Nov. 30-Dec. 31.

She says:

"From my modest home of more than a decade, I've appreciated the opportunity to observe and record some of my neighborhood's sightlines in paintings. Wildlife and trees, views of the nearby pond, and quiet peacefulness have reigned — until recently.

“Tremendous upheaval in my immediate surroundings has infused my plein air painting documentation with new urgency. Amid tree clearing, land excavation and construction activity adjacent to my home, I have continued to observe and paint. Many trees I've studied remain, but some are gone, cut down in their prime to make way for large new residences.

“As I experience these changing sightlines, the trees which remain have become my focus thanks to their steady, enduring, majestic and graceful presence.’’

What works for downtowns

Boston skyline on a windy, rainy day.

— Photo by Bert Kaufmann

In downtown Providence.

— Photo by Payton Chung

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Obviously, many jobs that have required being in a company’s office five days a week won’t be coming back, as remote work (whose adoption was rapidly accelerated by COVID) and artificial intelligence (which will probably destroy many millions of jobs) keep chomping away at them. This, of course, has presented a big challenge to city downtowns – some of which continue to report scary vacancy rates. But things aren’t as bad as has been presented, and indeed some downtowns are rebounding.

And even as employers have cut back on office space, more and more are demanding that employees who have been entirely remote return to the office at least several days a week. This requires precision planning! Good companies know that many good ideas, especially for problem-solving, come from in-person collaboration.

Hit these links:

https://centercityphila.org/uploads/attachments/clnkqulms0ngyngqdkvd1ozpk-downtowns-rebound-2023-web.pdf?utm_source=ccd&utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=downtowns&utm_id=report&utm_content=oct2023

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-10-31/despite-remote-work-downtown-nashville-is-thriving-for-residents-and-visitors?srnd=citylab

City officials are coming to realize that thriving downtowns will depend much more on recreational visitors and new and old residents drawn to their conveniences and cultural and other nonwork-related attractions and activities, and much less on workplaces (except the work done by staff at such places as restaurants, performance venues, museums and so on).

The Providence Food Hall, scheduled to open next year in the old Union Station, is an example of the exciting attractions that will keep people coming downtown as visitors and get some to want to live there. It will build on Rhode Island’s reputation as a food center.

BUT, the success of the food hall will depend to no small degree on the city stopping the social chaos and crime, and fear of crime, that sometimes envelop Kennedy Plaza. There are some fine examples of how public spaces that had become messes have been cleaned up and restored to the civic treasures that they had been. Consider Bryant Park, in Manhattan. (Thanks for the reminder, Brian Heller.)

Hit this link for an update on the Providence Food Hall project (named Track 15):

https://www.golocalprov.com/business/providence-food-hall-announces-name-and-initial-vendors

Downtown Providence is better positioned than many places to thrive in cities’ brave new world because of its walkable compactness, its colleges, whose students and staffs patronize local business, and the fact that a middle-and-upper-class neighborhood abuts it.

In Bryant Park, next to the New York Public Library.

— Photo by Kamel15

Mainers are like Norwegians

In far Downeast Maine Lubec, West Quoddy Head Lighthouse and Quoddy Narrows, with Grand Manan Island, Canada, in background.

“Almost everyone I spoke with in Maine who’s involved with the Arctic told me that Mainers have more in common with people from Iceland and Norway than they do with people from New York or California – they all live in relatively small communities with fairly extreme weather, and mainly depend on the ocean and other natural resources.”

Tatiana Kennedy Schlossberg (born 1990), environmental journalist, daughter of Caroline Kennedy Schlossberg and granddaughter of President John F. Kennedy

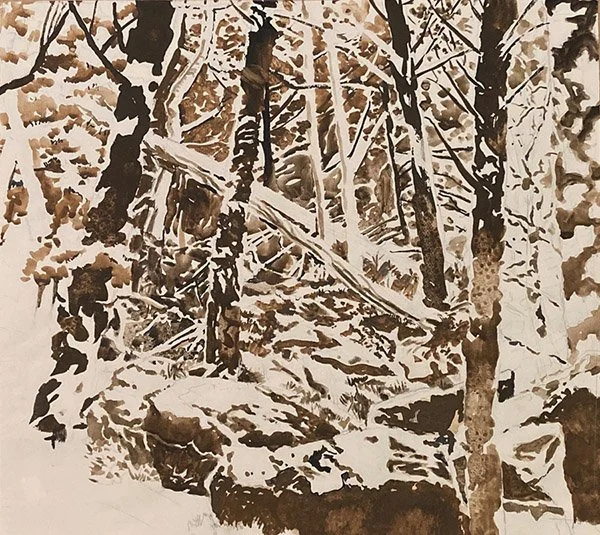

The woods are ready

“Forest Floor,’’ by Dan Hoftstadter, in his show “From Life: Drawings by Dan Hofstadter, ‘‘ at Atlantic Works Gallery, Boston, through Nov. 25.

The gallery says:

This is a show of “direct, perceptual drawings, unmediated by tools. The artist always keeps his sketchbook by his side, a constant companion to his work as an abstract painter and arts writer. Shown at the gallery are freehand landscapes – responses to wherever he was living at the time - along with portraits and figure studies.’’

Red memories

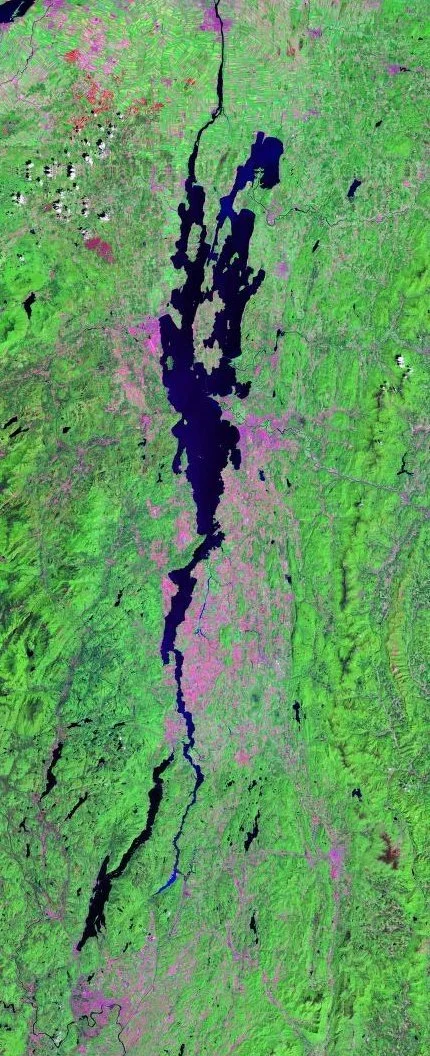

Cristine Kossow, “Summer by the Pound” (soft pastel), by Cristine Kossow, at Long River Gallery, White River Junction, Vt. She lives in Vermont’s (Lake) Champlain region.

Landsat photo of the immediate Lake Champlain region—only part of the much longer drainage basin and overall valley that reaches the Atlantic Ocean north of Nova Scotia via the St. Lawrence Seaway.

Daily Paintworks says Ms. Kossow:

“{E}njoys painting everyday objects, finding what is personal in the common items we all encounter --vintage tools; teacups; our animal friends; piles of produce; piles of anything really, because she loves the rhythm of repetition.

”Cristine has her prejudices. She likes to punctuate her work with a sneaky dash of periwinkle; it's her color. And she had a bitter feud with red for decades. But one summer, at the urging of a bumper crop of tomatoes, Cristine called an emotional truce and began a cascade of red musings that, in hindsight, mystify her.’’

Judith Graham: Who will care for elderly patients?

From Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Health News

Thirty-five years ago, Jerry Gurwitz was among the first physicians in the United States to be credentialed as a geriatrician — a doctor who specializes in the care of older adults.

“I understood the demographic imperative and the issues facing older patients,” Gurwitz, 67 and chief of geriatric medicine at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, in Worcester, told me. “I felt this field presented tremendous opportunities.”

But today, Gurwitz fears that geriatric medicine is on the decline. Despite the surging older population, there are fewer geriatricians now (just over 7,400) than in 2000 (10,270), he noted in a recent piece in JAMA. (In those two decades, the population 65 and older expanded by more than 60 percent) Research suggests each geriatrician should care for no more than 700 patients; the current ratio of providers to older patients is 1 to 10,000.

What’s more, medical schools aren’t required to teach students about geriatrics, and fewer than half mandate any geriatrics-specific skills training or clinical experience. And the pipeline of doctors who complete a one-year fellowship required for specialization in geriatrics is narrow. Of 411 geriatric fellowship positions available in 2022-23, 30 percent went unfilled.

The implications are stark: Geriatricians will be unable to meet soaring demand for their services as the aged U.S. population swells for decades to come. There are just too few of them. “Sadly, our health system and its workforce are wholly unprepared to deal with an imminent surge of multimorbidity, functional impairment, dementia and frailty,” Gurwitz warned in his JAMA piece.

This is far from a new concern. Fifteen years ago, a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded: “Unless action is taken immediately, the health care workforce will lack the capacity (in both size and ability) to meet the needs of older patients in the future.” According to the American Geriatrics Society, 30,000 geriatricians will be needed by 2030 to care for frail, medically complex seniors.

There’s no possibility that this goal will be met.

What’s hobbled progress? Gurwitz and fellow physicians cite a number of factors: low Medicare reimbursement for services, low earnings compared with other medical specialties, a lack of prestige, and the belief that older patients are unappealing, too difficult, or not worth the effort.

“There’s still tremendous ageism in the health-care system and society,” said geriatrician Gregg Warshaw, a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

But this negative perspective isn’t the full story. In some respects, geriatrics has been remarkably successful in disseminating principles and practices meant to improve the care of older adults.

“What we’re really trying to do is broaden the tent and train a health-care workforce where everybody has some degree of geriatrics expertise,” said Michael Harper, board chair of the American Geriatrics Society and a professor of medicine at the University of California-San Francisco.

Among the principles geriatricians have championed: Older adults’ priorities should guide plans for their care. Doctors should consider how treatments will affect seniors’ functioning and independence. Regardless of age, frailty affects how older patients respond to illness and therapies. Interdisciplinary teams are best at meeting older adults’ often complex medical, social, and emotional needs.

Medications need to be reevaluated regularly, and de-prescribing is often warranted. Getting up and around after illness is important to preserve mobility. Nonmedical interventions such as paid help in the home or training for family caregivers are often as important as, or more important than, medical interventions. A holistic understanding of older adults’ physical and social circumstances is essential.

The list of innovations geriatricians have spearheaded is long. A few notable examples:

Hospital-at-home. Seniors often suffer setbacks during hospital stays as they remain in bed, lose sleep, and eat poorly. Under this model, older adults with acute but non-life-threatening illnesses get care at home, managed closely by nurses and doctors. At the end of August, 296 hospitals and 125 health systems — a fraction of the total — in 37 states were authorized to offer hospital-at-home programs.

Age-friendly health systems. Focus on four key priorities (known as the “4Ms”) is key to this wide-ranging effort: safeguarding brain health (mentation), carefully managing medications, preserving or advancing mobility, and attending to what matters most to older adults. More than 3,400 hospitals, nursing homes and urgent care clinics are part of the age-friendly health system movement.

Geriatrics-focused surgery standards. In July 2019, the American College of Surgeons created a program with 32 standards designed to improve the care of older adults. Hobbled by the covid-19 pandemic, it got a slow start, and only five hospitals have received accreditation. But as many as 20 are expected to apply next year, said Thomas Robinson, co-chair of the American Geriatrics Society’s Geriatrics for Specialists Initiative.

Geriatric emergency departments. The bright lights, noise, and harried atmosphere in hospital emergency rooms can disorient older adults. Geriatric emergency departments address this with staffers trained in caring for seniors and a calmer environment. More than 400 geriatric emergency departments have received accreditation from the American College of Emergency Physicians.

New dementia-care models. This summer, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced plans to test a new model of care for people with dementia. It builds on programs developed over the past several decades by geriatricians at UCLA, Indiana University, Johns Hopkins University and the University of California at San Francisco.

A new frontier is artificial intelligence, with geriatricians being consulted by entrepreneurs and engineers developing a range of products to help older adults live independently at home. “For me, that is a great opportunity,” said Lisa Walke, chief of geriatric medicine at Penn Medicine, affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania.

The bottom line: After decades of geriatrics-focused research and innovation, “we now have a very good idea of what works to improve care for older adults,” said Harper, of the American Geriatrics Society. The challenge is to build on that and invest significant resources in expanding programs’ reach. Given competing priorities in medical education and practice, there’s no guarantee this will happen.

But it’s where geriatrics and the rest of the health-care system need to go.

Judith Graham is KFF Health News reporter.

Role reversal

“Upscale Your Den and Live Fully” (graphite and colored pencil on paper), by Boston-based artist Sammy Chong, in his show, opening Nov. 24, “Be Beast,’’ at 3S Artspace, Portsmouth, N.H.,

The gallery says:

“In Sammy Chong’s surreal drawings of endangered species, anthropomorphized animals are empowered as the dominant species in a hierarchical, fictional reality. Shining light on animal extinction, the work reminds viewers about the impact of our habits and choices on the world and its creatures.’’

Symbols of New England

The stone wall at the farm in Derry, N.H., where Robert Frost lived with his family in 1901-1911. He described the wall in his famous and complex poem "Mending Wall".

Stone wall in Maine

From the New England Historical Society:

“New England stone walls are as distinctive a feature of the landscape as bayous in Louisiana or redwoods in California. Hundreds of thousands of miles of them criss-cross the region like so much grillwork.’

Hit this link to read the article “Seven Fun Facts About New England’s Stone Walls.

Chris Powell: Maybe they can hide Conn. car tax

Toll booth on Connecticut’s Merritt Parkway in 1955. There are no longer toll roads in the Nutmeg State.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Most Connecticut state legislators purport to hate the car tax -- that is, municipal property taxes on automobiles. A special committee of the General Assembly has been created to review the tax and suggest alternatives for raising the billion dollars it pays into municipal government treasuries each year.

Since cars are sold more frequently, collecting the property tax on cars is more complicated than the property tax on residential and commercial property. Since the property tax on cars is not escrowed as property taxes on mortgaged properties usually are, car taxes fall unexpectedly on many people when the bills arrive from the local tax collector. As the economy weakens, poverty worsens, and more people live from paycheck to paycheck, the car tax is resented even more.

Another complaint is that the car tax is unfair because identical cars may be taxed much differently among towns. But this isn’t peculiar to the car tax; it’s a function of differences in local tax rates. Similar residential and commercial properties are taxed differently among municipalities as well because of different tax rates, and different rates are not necessarily bad, insofar as some municipalities choose to spend and tax much more than others.

Eight years ago a state law reduced the disparities in car taxes, imposing a car tax cap of 32.46 mills. According to the Waterbury Republican-American, the car taxes of 54 municipalities are capped -- that is, their general property tax rate is higher than the car tax cap. The disparities in taxes on similar cars have been reduced but often remain sharp.

A mill equals $1 of tax for each $1,000 of a property’s assessed value. Property tax is calculated by multiplying a property’s assessed value by the mill rate and dividing by 1,000. For example, a motor vehicle with an assessed value of $25,000 located in a municipality with a mill rate of 20 would have a property tax bill of $500.(The disparities in all municipal property tax rates result mainly from the concentration of poverty in the cities, which in turn results mainly from the concentration of the least expensive housing there and from the decision of municipal officials, under political pressure and the pressure of state labor law, to pay local government employees more generously, as well as from the inefficiency encouraged by large grants of state financial aid.

Inconvenient and unfair as the car tax may be, the real problem with it is that legislators and governors don't dislike it as much as they like the revenue it raises and the ever-increasing spending they require in state and municipal government. Indeed, the most obvious remedy for the dislike of the car tax isn’t even proposed -- to reduce municipal spending or reduce state spending and redirect the savings to municipalities.

As always, cutting spending is out of the question at both levels of government, even in the face of policies and programs that don’t achieve their nominal objectives. The broadest and most expensive policies and programs, like education and welfare for the able-bodied, are never audited for their failures. To the contrary, their failures are mistaken as evidence to do still more of what hasn’t accomplished what the public imagines the objectives to be.

That is, politically the status quo is loved far more than the car tax is hated.

Since even $100 million in spending cuts can’t be found in state and municipal budgets, how could state government find the billion dollars needed to eliminate the car tax?

Of course state Senate President Martin M. Looney, Democrat of New Haven, has his usual idea -- raising taxes on the wealthy, particularly on their capital gains. Progressivity in taxation is always a fair issue and matter of judgment, but in Connecticut it is meant less as justice than as protection for inefficiency and patronage.

Another idea is an 8 percent sales tax on homeowner and auto insurance policies. That wouldn't be more popular than the car tax, if people noticed it. But they wouldn't if it was levied against insurers on a wholesale basis, like the state’s wholesale tax on fuel and the taxes on electric utilities that are passed along hidden in electricity prices. Then the sales tax would be hidden in the price of insurance, and insurers, not state government, would be blamed for the price increases while legislators congratulated themselves for eliminating the car tax at last.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years. (CPowell@cox.net).

New program addresses economic welfare of patients

Edited from a New England Council report

“Boston Medical Center (BMC) recently announced it will allocate a $3 million grant from the MassMutual Foundation toward a program to support the economic welfare of pediatric patients and their families….

“The Economic Justice Hub will consist of three branches as BMC leads other hospitals in tackling inequalities in health-care access. The first branch will expand BMC’s StreetCred program–a free-tax-filing series started in 2016 that has returned more than $14 million to families and assisted them in opening 529 college savings accounts. The second branch will create new jobs for parents as peer educators and financial navigators to help other families in pediatrics seeking financial support. The third branch will facilitate a study on the ‘cliff effect,’ which occurs when a person’s wage increase triggers a disproportionate loss of government benefits, leaving families with limited resources to allocate toward healthcare, housing, food, and childcare.

“‘We know that wealth is directly tied to health,’ said Alastair Bell, M.D., MBA, president and chief executive BMC Health System. ‘Through initiatives like the Economic Justice Hub, we are building on BMC’s quality, compassionate care with family supports that address the economic inequities at the root of many health disparities. We are grateful for partners like the MassMutual Foundation who generously invest in this work, which can truly impact the healthy futures of our community.’’’

Increasingly resonates today

“Madness” (1941) (watercolor, gouache, ink and graphite on paper), by Arthur Szyk (1894-1951), in the show “In Real Times: Arthur Szyk: Artist and Soldier for Human Rights,’’ at Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum, through Dec. 16.

Courtesy of Taube Family. Arthur Szyk Collection, in The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, University of California at Berkeley.

Llewellyn King: Some veterans' suicides are linked to minute brain tears

Arizona Army and Air National Guard members participating in "Ruck for Life," an event promoting military suicide prevention.

World War II Memorial in the Fenway section of Boston.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

This is a horror story.

It is a story of suffering unmitigated and of death from despair. It is the story of our veterans who are 57 percent more likely to take their own lives than those who haven’t served their country.

Every day in the United States an average 17 veterans commit suicide. Those who have served in special combat force units, such as the Navy Seals, being a little more likely to die this way than regular forces.

These veterans are suffering and dying in plain sight. Veterans, whether they have seen action or not, are ending life by their own hands — hands that willingly took up arms to serve.

There is a clear and present crisis in deaths of those who have borne the battle, heard their country’s call and who die, often alone in despair.

Around Veterans Day we remember them, but what do we know of them?

More veterans have taken their own lives in the past 10 years than died in the Vietnam War. Frank Larkin, chairman of Warrior Call, an organization that asks anyone who knows a veteran to call them from time to time and ask, “How are you doing? What do you need? Can I get help for you?” But mostly to convey the comfort of knowing that “You are not alone.”

However, the problems are beyond loneliness and the well-known precursors to suicide: drug abuse, alcoholism, joblessness and broken relationships.

New research shows that what ails these sad heroes isn’t just psychological and moral despair, but physical brain damage -- minute tears in the brain that CT scans don’t pick up.

A leading researcher into brain injury and concussion, Dr. Brian Edlow, a professor at Harvard and associate director of the Center for Neurotechnology and Neurorecovery at Massachusetts General Hospital, said these tears are only discovered in postmortems, when the brain tissue is put under a powerful microscope.

The cause of these tears, Edlow told guest host Adam Clayton Powell III in a special Veterans Day episode of the television program White House Chronicle, are blasts that troops experience on the battlefield and in training — massive concussive blasts, over and over again. Those concerned emphasize that the victim doesn’t have to see combat to suffer damage, it happens in training as well.

Sometimes the tears are the result of a head injury such as a soldier’s head hitting the inside of a tank or a blast throwing a soldier against a wall, but mostly it is the shockwave, according to Edlow.

“Just to appreciate the scope of this problem, if you look at the post-9/11 generation, those who answered the call to serve after September 11, 2001, over 30,000 active-duty and veteran military personnel have died by suicide during that time period, which is four times more than the number of active-duty personnel who died in combat,” he said, adding that the “extent of the suicide problem is humbling.”

Larkin said that as many as two-thirds of those who commit suicide have never been to a VA hospital or sought institutional help.

For Larkin, the story is very personal. His son Ryan, a decorated Navy Seal who served for 10 years with four active-duty deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan, was a suicide.

Ryan returned from active duty a changed young man, 29 years old. He was moody, didn’t smile and showed classic signs of depression. His family couldn’t get him out of it and his brain scans were negative. After a year, he took his own life.

Earlier, Ryan had asked that his body be used for medical research. Postmortem diagnosis at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center revealed substantial brain damage that wasn’t detectable during the year before his death, his father said.

“The system didn’t know what to do and it defaulted toward psychiatric diagnosis,” Larkin said.

Referring to scans and other techniques now in use to examine the brain, Edlow said, “We simply are not accurate enough to detect these sub-concussive blast-related injuries.”

Ryan’s tragedy is repeated 17 times every day — and that figure doesn't account for those who die in deliberate accidents and are otherwise not reported as suicide, Larkin said.

While medical science and the military catch up, all we can do, as Larkin said, is to check on a veteran, any veteran. You could save a life, bring a man or woman back from the precipice.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.,

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

‘First they came….’

This is the "First they came..." poem attributed to German theologiian and Lutheran minister Martin Niemoeller (1892-1984) at the Holocaust memorial in Boston.

Frank Carini: The brazen and well-financed disinformation campaign of the anti-wind-farm crowd

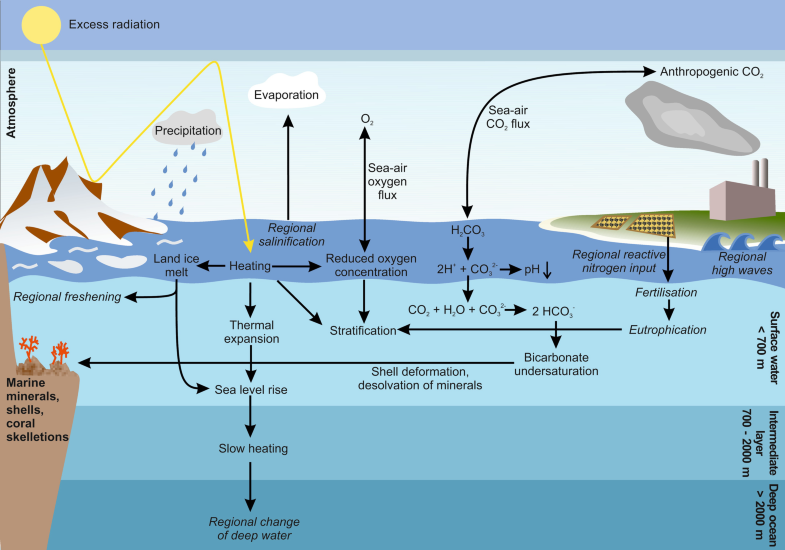

Overview of climatic changes caused by burning fossil fuel and their effects on the ocean. Regional effects are displayed in italics.

Oil spill covering kelp.

The anti-wind mob chums the waters with red herring. The conspiracy theorists continue to hide behind critically endangered North Atlantic right whales to spin tales about offshore wind. Their faux concern is nauseating.

When it comes to the real threats to the 350 or so North Atlantic right whales left on the planet — entanglements with fishing gear and strikes with ships — the mob’s ranting and raving goes largely silent, and my stomach turns.

These self-proclaimed pro-whale warriors only care about the lives of these majestic marine mammals when they fit into their manufactured hysteria about offshore wind.

Among those spreading the mob’s propaganda are southern New England firebrand Lisa Quattrocki Knight, president of Green Oceans, and Constance Gee, a Westport, Mass., resident and Green Oceans member; Lisa Linowes, executive director of the Industrial Wind Action Group Corp, also known as The WindAction Group; Protect Our Coast New Jersey; and blogger Frank Haggerty, a blowhole of offshore wind misinformation.

Their bluster is either funded by the fossil-fuel industry and/or they are wealthy coastal property owners more concerned that their ocean views will be ruined by a different type of energy infrastructure. Either way, the lives of whales, dolphins, birds, and humans living near polluting fossil-fuel operations don’t matter.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Beats thinking

“Muscle Memory” (monoprint drypoint construction with violin and mirror), by Massachusetts artist Debra Olin, at Brickbottom Artists Association’s (Somerville, Mass.) members show, through Nov. 19.