Llewellyn King: As the electricity sector is reinvented, there's an urgent need for engineers and technicians to support them

At the new (founded 1997) but already highly prestigious Olin College of Engineering, in Needham, Mass.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have a soft spot for engineers and engineering. It started with my father. He called himself an engineer, even though he left school at 13 in a remote corner of Zimbabwe (then called Southern Rhodesia) and went to work in an auto repair shop.

By the time I remember his work clearly, in the 1950s, he was amazingly competent at everything he did, which was about everything that he could get to do. He could work a lathe, arc weld and acetylene weld, cut, rig, and screw.

My father used his imagination to solve problems, from finding a lost pump down a well to building a stand for a water tank that could supply several homes. He worked in steel: African termites wouldn’t allow wood to be used for external structures.

Electricity was a critical part of his sphere; installing and repairing electrical-power equipment was in his self-written brief.

Maybe that is why, for more than 50 years, I have found myself covering the electric-power industry. I have watched it struggle through the energy crisis and swing away from nuclear to coal, driven by popular feeling. I have watched natural gas, dismissed by the Carter administration as a “depleted resource,’’ roar back in the 1990s with new turbines, diminished regulation, and the vastly improved fracking technology.

Now, electricity is again a place of excitement. I have been to four important electricity conferences lately, and the word I hear everywhere about the challenges of the electricity future is “exciting.”

James Amato, vice president of Burns & McDonnell, a Kansas City, Mo.-based engineering, construction, and architecture firm that is heavily involved in all phases of the electric infrastructure, told me during an interview for the television program White House Chronicle that this is the most exciting time in supplying electricity since Thomas Edison set the whole thing in motion.

The industry, Amato explained, was in a state of complete reinvention. It must move off coal into renewables and prepare for a doubling or more of electricity demand by mid-century.

However, he also told me, “There is a major supply problem with engineers.” The colleges and universities aren’t producing enough of them, and not enough quality engineers — and he emphasized quality — are looking toward the ongoing electric revolution, which, to those involved in it, is so exhilarating and the place to be.

This problem is compounded by a wave of age retirements that is hitting the industry.

I believe that the electricity-supply system became a taken-for-granted undertaking and that talented engineers sought the glamor of the computer and defense industries.

Now, the big engineering companies are out to tell engineering school graduates that the big excitement is working on the world’s biggest machine: the U.S. electric supply system.

My late friend Ben Wattenberg, demographer, essayist, presidential speechwriter, television personality, and strategic thinker, hosted an important PBS documentary film and co-wrote a companion book, The First Measured Century: The Other Way of Looking at American History. He showed how our ability to measure changed public policy as we learned exactly about the distribution of people and who they were. Also, how we could measure things down to parts per billion in, say, water.

In my view, this is set to be the first engineered century, in tandem with being the first fully electric century. We are moving toward a new level of dependence on electricity and the myriad systems that support it. From the moment we wake, we are using electricity, and even as we sleep, electricity controls the temperature and time for us.

The new need to reduce carbon entering the atmosphere is to electrify almost everything else, primary transportation — from cars to commercial vehicles and eventually trains — but also heavy industrial uses, such as making steel and cement.

Amato said there is not only a shortage of college-educated engineers needed on the frontlines of the electric revolution but also a shortage of competent technicians or those trained in the crafts that support engineering. These are people who wield the tools, artisans across the board. In the electric utilities, there is also a need for line workers, a job that offers security, retirement, and esprit.

In the 1960s, the big engineering adventure was the space race. Today, it is the stuff that powers your coffeemaker in the morning, your cup of joe, or, you might say, your jolt of electrons.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and is based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Editor’s note: Readers should read about this Massachusetts-based company.

Llewellyn King: Artificial intelligence and climate change are making 2023 a scary and seminal year

Global surface temperature reconstruction over the last 2000 years using proxy data from tree rings, corals and ice cores in blue. Directly observed data is in red.

The iCub robot at the Genoa science festival in 2009

— Photo by Lorenzo Natale

His job is probably secure.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

This is a seminal year, meaning nothing will be the same again.

This is the year when two monumentally new forces began to shape the way we live, where we reside and the work we do. Think of the invention of the printing press around 1443 and the perfection of the steam engine in about 1776.

These forces have been coming for a while, they haven’t evolved in secret. But this was the year they burst into our consciousness and began affecting our lives.

The twin agents of transformation are climate change and artificial intelligence. They can’t be denied. They will be felt and they will bring about transformative change.

Climate change was felt this year. In Texas and across the Southwest, temperatures of well over 100 degrees persisted for more than three months. Phoenix had temperatures of 110 degrees or above for 31 days.

On a recent visit to Austin, an exhausted Uber driver told me that the heat had upended her life; it made entering her car and keeping it cool a challenge. Her car’s air conditioner was taxed with more heat than it could handle. Her family had to stay indoors, and their electric bill surged.

The electric utilities came through heroically without any major blackouts, but it was a close thing.

David Naylor, president of Rayburn Electric, a cooperative association providing power to four distribution companies bordering Dallas, told me, “Summer 2023 presented a few unique challenges with so many days about 105 degrees. While Texas is accustomed to hot summers, there is an impactful difference between 100 degrees and 105.”

Rayburn ran flat out, including its recently purchased natural gas-fired station. It issued a “hands-off” order which, Naylor said, meant that “facilities were left essentially alone unless absolutely necessary.”

It was the same for electric utilities across the country. Every plant that could be pressed into service was and was left to run without normal maintenance, which would involve taking it offline.

Water is a parallel problem to heat.

We have overused groundwater and depleted aquifers. In some regions, salt water is seeping into the soil, rendering agriculture impossible.

That is occurring in Florida and Louisiana. Some of the salt water intrusion is the result of higher sea levels and some of it is the voracious way aquifers have been pumped out during long periods of heat and low rainfall.

Most of the West and Florida face the aquifer problem, but in coastal communities it can be a crisis — irreversible damage to the land.

Heat and drought will cause many to leave their homes, especially in Africa, but also in South and Central America, adding to the millions of migrants on the move around the world.

AI is one of history’s two-edged swords. On the positive side, it is a gift to research and especially in life sciences, which could deliver life expectancy north of 120 years.

But AI will be a powerful disruptor elsewhere, from national defense to intellectual property and, of course, to employment. Large numbers of jobs, for example, in call centers, at fast-food restaurant counters, and check-in desks at hotels and airports will be taken over by AI.

Think about this: You go to the airport and talk to a receptor (likely to be a simple microphone-type of gadget on the already ubiquitous kiosks) while staring at a display screen, giving you details of your seat, your flight — and its expected delays.

Out of sight in the control tower, although it might not be a tower, AI moves airplanes along the ground, and clears them to take off and land — eventually it will fly the plane, if the public accepts that.

No check-in crew, no air-traffic controllers and, most likely, the baggage will be handled by AI-controlled robots.

Aviation is much closer to AI automation than people realize. But that isn’t all. You may get to the airport in a driverless Lyft or Uber car and the only human beings you will see are your fellow passengers.

All that adds up to the disappearance of a huge number of jobs, estimated by Goldman Sachs to be as many as 300 million full-time jobs worldwide. Eventually, in a re-ordered economy, new jobs will appear and the crisis will pass.

The most secure employment might be for those in skilled trades — people who fix things — such people as plumbers, mechanics and electricians. And, oh yes, those who fix and install computers. They might well emerge as a new aristocracy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: The folly of Biden on the picket line

The Cambridge Assembly building, which started as a Ford Motor Co. factory in Cambridge, Mass., which opened in 1913. It had the first vertically integrated assembly line in the world. It was replaced in 1926 by the Somerville Assembly. The plant was later reused by Polaroid Corp., once Greater Boston’s high-tech star, and is now owned by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

This is a revised version of a column posted earlier this week.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The United Auto Workers strike against the Big Three U.S. automakers, Ford, General Motors and Stellantis, formerly Chrysler, no matter the merits of the workers’ yearnings, shouldn’t have happened. Once it got going, it shouldn’t have lasted. The White House should have spoken.

Already there is damage. Ford has “paused” plans to build a $3.5-billion battery plant in Michigan. If the strike drags on, or if the industry bows to the most damaging demand in the union’s wish list (a 32-hour work week), then the production of EVs and battery leadership will be ceded to other countries. U.S. automakers’ dependence on China — the world ’s top battery maker for EVs — will continue.

The U.S. auto industry is starting its EV surge behind others, and it will suffer mightily if the UAW doesn’t return to work.

In this circumstance, with so much at stake, it would be reasonable to expect President Biden to have both sides closeted at Camp David and to be “knocking heads together.”

The president is the ultimate arbitrator, the one we look to for guidance and to tell us what is best. Yet, instead of bringing both sides together in the national interest, Biden has chosen sides, and chosen to walk the picket line.

Even Steven Rattner, the Democrats’ mechanic when it comes to auto issues, has said this is wrong.

Rattner — whom I caroused with when he was reporter at The New York Times, before he became fabulously rich on Wall Street — is through-and-through a Democrat and one of the party’s intellectuals. In 2009, he authored the rescue plan for the auto industry. At that time, it looked like General Motors and Chrysler were headed for permanent closure.

What was Biden thinking? Why did he abandon the high ground of the presidency?

How can Biden now sit down and bring both sides to the table to negotiate in good faith? He has already declared his allegiance to one.

I believe in the value of unions: guarantors of middle-class life for many. I am not just saying that. I have lived it.

I was once the president of the Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild. I am very proud of the financial settlement we got on my watch for reporters and editors at The Washington Post. It was a breakthrough: a 67 percent pay raise over three years.

The newspaper industry was very prosperous at the time, whereas reporters and editors were poorly paid. It was long before the internet would crush the industry, reducing it to its present state of poverty and collapse. We were asking for some of the goodies we had created. There was no danger of The Washington Post moving to China.

Sadly, the unions have been slow to adjust to new realities. They are stuck in a mindset of the days when we were a country of industrial robber barons and industrial unions made sense. Now we are mostly a service economy desperately seeking to reindustrialize. EVs are important in that effort.

I ran into outdated union thinking head-on at the Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild. Although we were largely autonomous, we were a chapter of the American Newspaper Guild, our head office.

I had a proposal for simplifying work schedules for editorial staff. My proposal was that editorial staff work three days — 10 to 12 hours a day — and have three days off. My colleagues loved it, The Washington Post management saw it as a solution to overtime and weekend staffing problems. I had seen it work well at the BBC in London, where it was standard practice.

The ANG head office went berserk: It was a betrayal of union history and the “model” contract, written by the legendary reporter, columnist and ANG founder, Heywood Broun, in 1935. In ongoing negotiations with The Post, I dropped the proposal to everyone’s regret. That kind of legacy thinking is what has been killing unions and unionism.

There is a backstory to the Hollywood writers’ strike and the auto workers’ stoppage: artificial intelligence. It will change lives and is a threat to the kind of work unions have protected.

Biden might well have chosen the strikes as a chance to bring about settlements, but also to begin a national dialogue on AI.

Instead, Biden walked a picket line, resolving nothing.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: The dangerous cheapening of the impeachment process

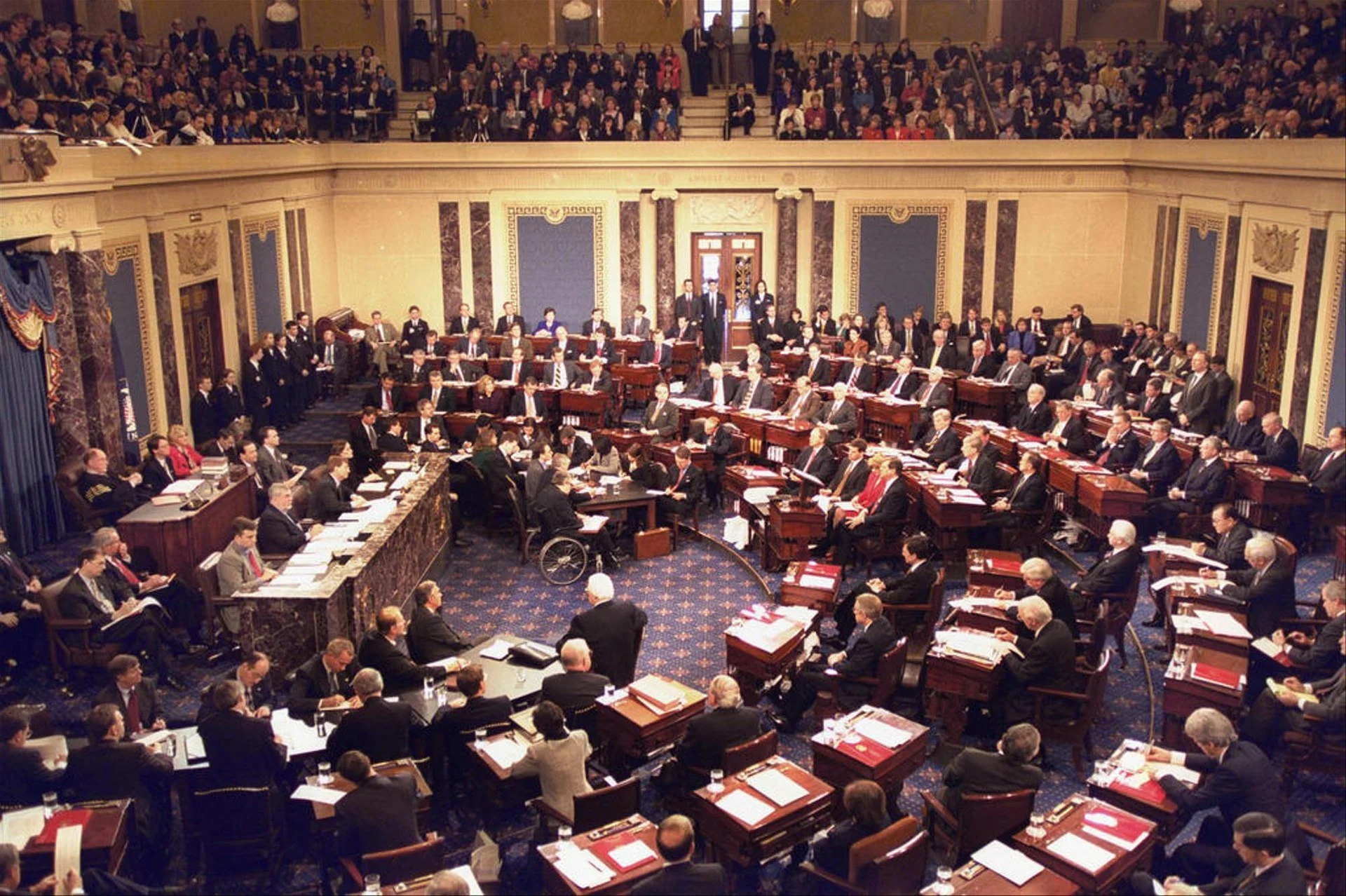

The impeachment trial of Bill Clinton, in 1999, with Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist presiding. The House managers are seated beside the quarter-circular tables on the left and the president's personal counsel on the right, much in the fashion of President Andrew Johnson's trial, in 1868.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Edmund Burke, the 18th-Century British statesman, argued during the celebrated impeachment of Warren Hastings, the governor of Bengal, that impeachment was essentially a political process, not a judicial one. Quite so.

The political dimension of impeachment is again on display in Washington, where the Republicans, driven by a faction of the party, are moving toward impeaching President Biden.

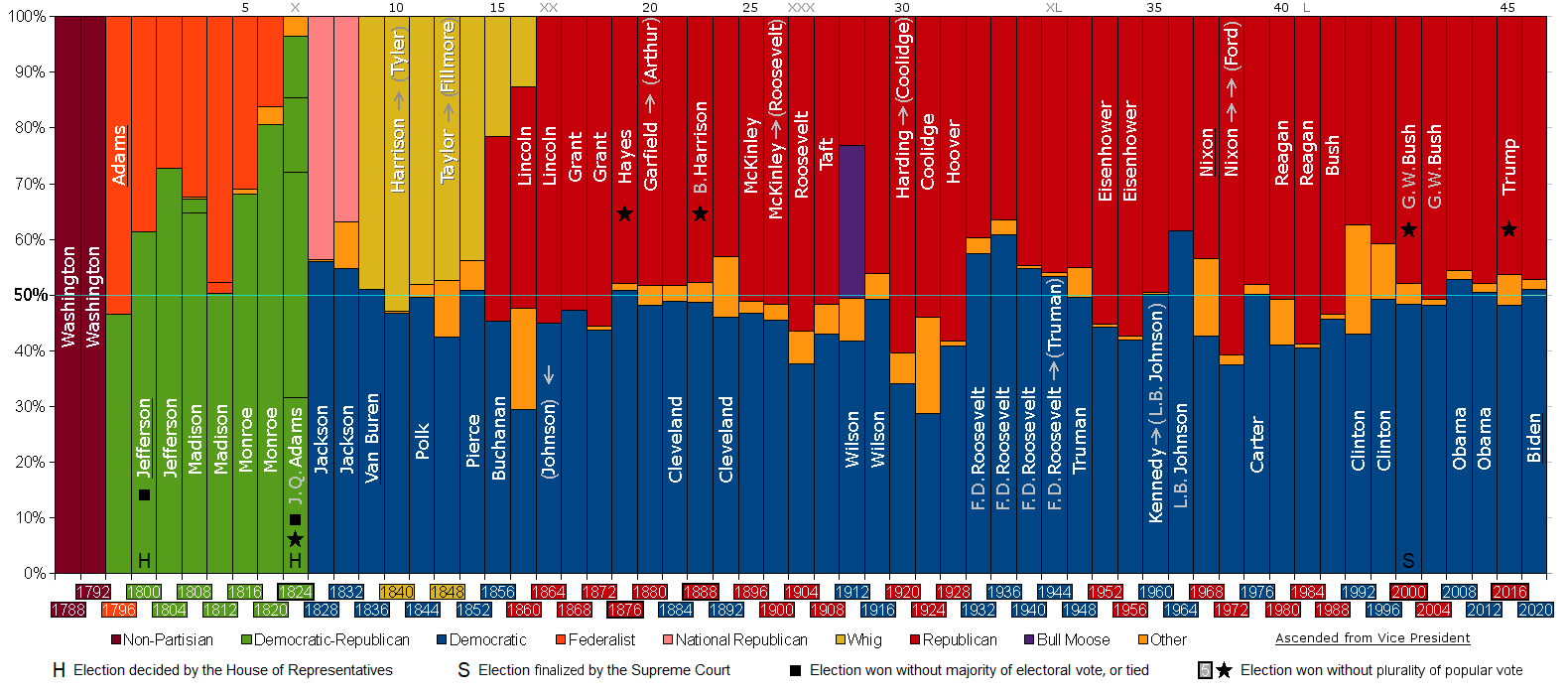

Historically, presidential impeachment has been reserved for actions that meet the undefined standard of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” It has been used with great restraint; until the impeachment of Bill Clinton, only Andrew Johnson had been impeached. The bar was lowered for the Clinton action then, and the attempt to impeach Biden is a further lowering — pointing up that it is, as Burke argued, a political process.

Impeachment is becoming a common political tactic not, as envisaged by the Founders, the ultimate censure, leading to a trial in the Senate and removal from office.

The two indictments of Donald Trump would seem to have met, to my mind, the constitutional standard and, had the Senate been in other hands, might have led to a trial and removal. It is argued that those indictments didn’t meet the standard and were no more than censure by another name, carried out along party lines.

The gravity of impeachment has been preserved since the beginning of the republic, but it is in danger.

Some aspects of the structure of the state should be out of reach to the political process most of the time. The U.S. Constitution guarantees that it can’t be easily amended or today it wouldn’t be recognizable, as every fashionable fixation would have been added. The mistake of Prohibition written again and again.

At the time that the Northern Ireland peace accords were being written, I was involved with a lively summer school in Ireland — which might be thought of as a think tank that meets once a year.

This organization, the International Humbert Summer School, studied Ireland’s relationship to the world, but became involved in the peace process. There were speakers from both the Unionists (pro-British) and Sinn Fein, the political wing of the IRA.

At one session, my role was to respond to the late Martin McGuinness, widely known as a top leader of the IRA, believed by the British to be a terrorist with blood on his hands.

Because I have a British accent, the organizers, John Cooney, the Irish historian and journalist, and Tony McGarry, a prominent local headmaster in Ballina, County Mayo, where we gathered, were nervous about what I might say to a man who was regarded with fear and awe as a killer.

Our event turned into a debate. McGuinness was sharp, had a good sense of humor and was open to ideas. Because the IRA had been engaged in armed struggle for so long, it hadn’t thought about constitutional arrangements in peace.

Thinking of the U.S. Constitution, I suggested to McGuinness that if a new constitution for Northern Ireland were to be written, it should sweep nothing under the carpet by ignoring it (as was the American case with slavery) and that when finished, it should be placed on “a high shelf” from which it couldn’t be easily taken down.

McGuinness agreed heartily, and this led to a discussion of constitutions and systems of government, and how the drafting could be perfected.

But my idea of a high shelf was what stuck with him.

So it is deeply disheartening to see impeachment treated as just another political tactic to be launched against any American president simply because the opposition party doesn’t like the president’s policies. But that is what is happening.

Incidentally, the impeachment of Warren Hastings, which dragged on for years and was enormously expensive, ended in acquittal before the House of Lords, proving Burke’s point that impeachment was a political process.

In the United States, for most of our history we have avoided keeping it out of the political maelstrom. It is a sad thing to see used now as a purely political tactic.

We have what is essentially a permanent campaign for the presidency. No sooner is one election certified then rumblings about the next one, with all the attendant speculation, begin.

Will presidential impeachment become part of the political process? And what if a Senate has the two-thirds majority to convict on political grounds? There is danger here.

At the end of our exchange, I wished the IRA leader “the best of British luck.” He laughed. No attempt to kneecap me followed.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Memories of people I knew from the Manhattan Project; beautiful "Barbie'

Important sites in the Manhattan Project. Alamogordo is where the first atomic bomb was detonated, on July 16, 1945. The map would have been better if it had included the site of uranium 238 refining for the project by Metal Hydrides Inc., in Beverly, Mass.

Edward Teller’s (1908-2003) badge photo at the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos, N.H., facility. Called “The Father of the Hydrogen Bomb,’’ he was seen as an inspiration for the eponymous scientist in Stanley Kubrick’s classic 1964 black comedy Dr. Strangelove.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have been to the movies. I haven’t done that since before the COVID shutdown.

I went to see two huge movies that have each grossed $1 billion so far, and I enjoyed them enormously. They are, of course, Barbie and Oppenheimer.

I went to see Barbie because I thought I should know what people were discussing. I went to see Oppenheimer because, in a sense, I have skin in that game. I knew a few people who worked on the Manhattan Project, and two of them were characterized in the movie: Hans Bethe and Edward Teller, known as the father of the hydrogen bomb.

About Barbie: It is a fantasy romp filled with popular, real-life messages. I had to see how director Greta Gerwig would make an adult movie about a doll, albeit a storied one — with brilliant imagination is how.

Oppenheimer, by contrast, is a major cinematic work, a remarkable recapturing of history and character development on the screen. Christopher Nolan is a director at the top of his game. He deserves a comparison with Orson Welles and David Lean.

Across the board, it is a triumph, compelling and true to the facts and the personalities. The evocative recreation of Los Alamos as it must have been, of the tower from which the first nuclear device was detonated, rings true. I have crawled all over the nuclear-test site and spent many hours at Los Alamos, where I used to give an annual lecture on energy or the relationship of humans to science.

In November 1975, Bethe and another veteran of the Manhattan Project, Ralph Lapp, and I put together a panel of 24 Nobel laureates (including Bethe) to defend civilian nuclear power. We got them all together on a stage at the National Press Club, in Washington. I had hoped that it would be a seminal event, ending some of the nonsense being spread about nuclear radiation.

Ralph Nader took up arms against us and assembled 36 Nobel laureates who were cool to nuclear. Ours were physicists, engineers and mathematicians who had a vast understanding of nuclear and endorsed it enthusiastically.

We didn’t win. Bethe, as I recall, was philosophical about being trounced.

I first met Teller in Geneva. I was to introduce him at a conference, and we had breakfast together. He seemed distracted and confused. But he was in top form when he spoke.

Later, I got to know him better. He gave a series of speeches for conferences I had organized on the Strategic Defense Initiative — colloquially known as Star Wars. He often sat slumped in his chair, clutching his enormous walking stick. But he stood erect on the podium, arguing vigorously the case for Ronald Reagan’s program.

The Oppenheimer movie reminded me of two institutions I covered intensely as a reporter: the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and its congressional overseer, the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy.

The committee was supposed to check the AEC. The AEC was a tool of the powerful and wildly pro-nuclear committee — the only joint committee empowered to introduce legislation in both houses of Congress. The reality of that partnership was that the committee proposed and the AEC disposed.

The movie is extraordinary in capturing the workings of Congress and how a nod or a smile can put great events in motion.

This understanding of the nuances and mores of Washington, and particularly the arcane theatricality of the congressional hearings, is accurate in ways seldom captured on film. This is more surprising given that the director is an Englishman who lives a very private life in Los Angeles.

I leave it to sociologists to ponder how two movies as different as Barbie and Oppenheimer could open simultaneously, becoming huge hits. If you see these movies, especially Oppenheimer, see them in the theater. They deserve that big-screen and wraparound-sound environment.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

White House Chronicle

Llewellyn King: Is Biden perilously trying to hide his age?

“Old Age’’, by Robert Smirke (1752-1845), British painter

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Is Joe Biden hiding in plain sight?

Is his most extensive public effort these days fending off signs of age, hiding his infirmities, and clinging to the hope that he can still win in the election just over a year from now?

Sotto voce, the savants of the Democratic Party worry and complain in private that Biden is too old and infirm and should move over before it is too late. In public, they point to the health of the economy, receding inflation and the high employment rate, and foreign-policy wins.

But indeed, the Joe Biden of today isn’t the Joe Biden of yesterday.

The Biden we in the corps knew over the years in Washington was accessible, friendly, keen to please — and he talked. How he talked. Biden would give a speech, but he didn’t stop. He seemed to tack a second speech onto the first.

Biden didn’t change the course of history with his eloquence, nor set the audience to thinking in ways they hadn’t previously, but he was easy to take.

Now, he seems to approach the podium with caution, reading the speech with a just-get-me-through-this stoicism. The man who used to love the microphone appears to fear it.

Likewise, the man who used to enjoy the cut and thrust of interacting with the press eschews press conferences. He doesn’t hold them.

This absence of press conferences isn’t unimportant. They are messy and unruly, but they are where the acuity of the leader is tested and on display. They are where we might get a look at how he might be in negotiation with foreign leaders.

Press conferences are part of the democratic process, where the president reports to the public through the press. Like question time in the British House of Commons, they are where we see the president in action.

Boastful press releases — which every administration puts out — are no substitute. The nation deserves to see the president in action. Everything else is curated image-building by the White House staff.

A few questions tacked on ritually to the end of joint appearances with foreign heads of state aren’t a substitute. They are Potemkin affairs.

Republicans would love to bear down more on Biden’s age, but dare not. Their frontrunner, Donald Trump, is 77 — only three years younger than Biden; and, at 81, the Republican leader in the Senate, Mitch McConnell, is showing signs of health challenges linked to age.

Trump’s age is less discussed because his epic legal problems distract from whether he also might be too old.

The sad end of Winston Churchill’s political career should be a warning for all who cling to office too long.

The Conservative Party under Churchill lost the election immediately after World War II but was returned to office in 1951, and Churchill became prime minister for the second time. He was about to turn 77. Health warnings were ignored by his party and by his family.

The infirmities of age got in the way. Churchill was often confused, and new issues baffled him, said his friend the publisher Lord Beaverbrook.

According to historian Roger Scruton, during Churchill’s second administration, the seeds of what would haunt Britain later were sown: He failed to arrest the open border flow of immigrants from the former empire or to check the growth of trade-union power.

When Churchill, retired in 1955, his longtime deputy, Anthony Eden, took over and led the disastrous attempt to seize the Suez Canal in 1956.

Biden’s uncertain future is exacerbated by the seeming shortcomings of Vice President Kamala Harris. Despite attempts to bolster her, such as referring in press releases to the Biden-Harris administration, she is reportedly inept.

She is known to have had difficulty with her staff. In public, she appears frivolous, laughing inappropriately and showing little grasp of issues. She has left no mark on significant assignments handed to her by Biden, including immigration, voting rights and the influence of artificial intelligence.

No wonder a late-August poll from The Wall Street Journal showed 60 percent of eligible voters think that Biden isn’t “mentally up for the job of president.” In a CNN poll, 73 percent of Americans say they are seriously concerned that Biden’s age might negatively affect his current physical- and mental-competence level.

Churchill’s sad political decline shows even great men grow old. Biden can be seen on television going here and there: a blur of travel. But is this a man in hiding from a truth — his age?

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Wherein we go cruising for out-of-control tourism

Costa Mediterranea in Argostoli, Greece

— Photo by Kefalonia2015

Huge cruise ship at Bar Harbor, Maine. Cruise ships are increasingly irritating many locals in famous tourist spots in New England in the cruise lines’ May-October season.

Europe reeled this summer from heat, wildfires, migrants and worries about Russia’s war in Ukraine, but also from too much tourism. I know, I was part of the problem.

Tourism is the quick economic fix for poor nations, but it is also important to rich ones — until both get too much of it.

The places everyone wants to visit, often places on bucket lists, are choking on their success. Paris, Britain’s Stonehenge and the Lake District, Ireland’s Ring of Kerry and the jewels of Italy, Florence and Venice, all suffer summer overload.

Things were so bad in Venice this summer that cruise ships had to be waived off. The Greek islands of Santorini, Corfu and Mykonos were, likewise, inundated with cruisers and other tourists.

Yet tourism is vital to many economies. The emerging tourist destinations along Croatia’s Dalmatian Coast are the latest to feel the benefits and problems of tourism. The sites, the roads and the facilities are stretched, but tourism has meant economic well-being for the region, especially as cruise ships have started calling.

Cruise ships, those big – and becoming gigantic — floating palaces overwhelm ports when they anchor, burden infrastructure and deposit lots of lovely money.

Greece and many countries along the Adriatic Sea derive about 25 percent of their GDP from tourism, not the least of it from cruise ships. Cruise ships are very important to any shore community that has ancient ruins, historical and scenic cities, natural wonders — and the Balkan countries have all in abundance.

In early August, my wife and I cruised the Dalmatian Coast and Greek islands. When we booked the cruise, at the last minute, we were fully aware of the tourist pressure on Europe every summer, but learned that it is getting worse.

Most of the Dalmatian Coast is still visitable in summer and hugely rewarding, except for Dubrovnik, which we skipped. It is, I learned, showing stress from over-tourism. The full impact of the cruise ships hasn’t yet begun to wear on the small coastal towns, as it has on the most famous Greek islands.

You can’t pick a Greek islands itinerary in the summer that will avoid seeing too many cruise ships, carrying 2,500 and up passengers, arriving at the same destination at the same time.

Fira, on Santorini, is a fabulous cliff town, except when there are too many visitors going ashore from a flotilla of cruise ships anchored in the harbor.

Five cruise ships arrived at Fira simultaneously, ours among them, and untold thousands of tourists went ashore. To reach the charming town, you must ride a donkey or a cable car. My wife and I love donkeys, so we opted for the cable car. It was chaotic, verging on dangerous. Extraordinarily, the crowds waiting for hours to board the cable cars were well-behaved: no pushing, no audible outrage, just resigned queuing.

Lest you think cruise ships are filled only with Americans, cruising has become a global passion.

Cruisers see the world from the comfort and security of a very large, well-organized hotel that moves with them. They see so much more and take their selfies in so many more places than they could otherwise.

Cruising is big business, and the size of the ship seems not to deter anyone.

Royal Caribbean is about to add its Icon class: They will carry up to 7,000 passengers and 3,000 crew. To merchants and tax collectors they are golden galleons as the visitors spend their doubloons on tours, trinkets, meals and tips.

But over-tourism degrades the picturesque ports, cherished villages, and great structures of the past.

When I see a cruise ship, towering over a town from where history was born, I think: The barbarians arrive in shorts, clutching cameras and cell phones. I may be one of them, but I shall endeavor to avoid high summer in the future.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Fall down before a Frankenstein deity

How deep learning is a subset of machine learning and how machine learning is a subset of artificial intelligence

— From British Wikipedia

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Those who work with language have reason to worry about the effect of artificial intelligence and its awesome skill with words.

You can, for example, ask ChatGPT to write an article on almost any subject, and it will mostly come back with something ready for the page, untouched by a human editor. If you want it in Washington Post style and it is in Guardian style with British spelling, faster than you can type in the request, it will reformat the article into the style and usage you want and, presto, it is ready to print or publish digitally.

Writers, lawyers and college professors will feel the sting first. Writers in Hollywood are on strike because of the threat posed. College professors are going into the new term unsure whether they will deal with original work or whether students are substituting AI-generated essays and theses.

Journalists, already reeling from the closure of so many newspapers, are wondering about their future.

But what about religion?

AI ramifications in organized religion are good and bad. In fringe religions and cults, it will be open season on worshipers. And some will find comfort in speaking to God as though the Almighty is resident in AI.

On the good side, many pastors approach Sunday in trepidation. The sermon, which is supposed to be instructional, uplifting and erudite, is a source of torture to those who aren’t good writers or have difficulty sharing their own faith with the congregation.

There are newsletters to help sermon writers and a wealth of diocesan support. Still, sermons are a trial for many pastors. You can read an old sermon or plagiarize another cleric, but that leaves sincere preachers feeling they are cheating and letting their congregants and their mission down.

Enter AI. By feeding a few thoughts to a chatbot, a polished sermon incorporating some of the preacher’s ideas appears almost instantly.

This hasn’t been wasted on the established churches, I learn from the BBC. The churches are looking at ways of embracing AI, using it as a tool, a gift to help with preaching and pastoral work, comforting the sick, composing notes of sympathy, and research.

The rub comes when people, as some surely will, confuse concepts of God with AI simulations and start to think that AI is a deity.

It has the characteristics usually associated with a deity: ubiquitous and seemingly all-knowing.

Indeed, it may claim to be a god if it hallucinates, as it sometimes does. What, then, for the unsuspecting? Do they fall to their knees?

I asked ChatGPT, and it sent me a 10-point list of the possibilities, noting that it is a subject that is complex and evolving.

These three points are scary:

—“Customized Spiritual Experiences: AI algorithms could be designed to tailor spiritual experiences to individual preferences and beliefs. These experiences might include personalized prayers, meditation sessions, or virtual pilgrimages, designed to resonate with each person’s spiritual inclinations.”

—“Ethical Dilemmas and Moral Guidance: AI might be used to explore complex ethical questions and provide guidance based on religious teachings. For instance, AI systems could analyze various religious perspectives on a given moral issue and help individuals navigate their choices.”

—“Exploration of Spirituality and Philosophy: AI’s ability to process vast amounts of information could be harnessed to delve deeper into philosophical and spiritual questions, potentially offering new perspectives on the nature of existence, consciousness and the divine.”

Would it be safe to call it Frankenstein worship?

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Dartmouth Hall at the eponymous college in Hanover, N.H.

Editor’s note. This is from the Council of Europe:

“The term ‘AI’ could be attributed to John McCarthy of MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), which Marvin Minsky (Carnegie-Mellon University) defines as ‘the construction of computer programs that engage in tasks that are currently more satisfactorily performed by human beings because they require high-level mental processes such as: perceptual learning, memory organization and critical reasoning. ‘ The summer 1956 conference at Dartmouth College (funded by the Rockefeller Institute) is considered the founder of the discipline. Anecdotally, it is worth noting the great success of what was not a conference but rather a workshop. Only six people, including McCarthy and Minsky, had remained consistently present throughout this work (which relied essentially on developments based on formal logic).’’

Llewellyn King: We're lonely in our boxes

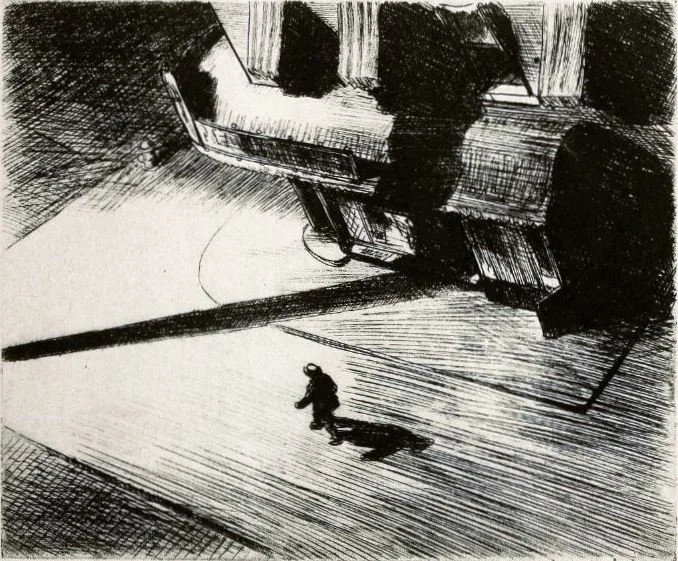

“Night Shadows’’ (1922 etching), by Edward Hopper, created for the magazine Shadowland.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The nation, I read, is in the grip of a loneliness epidemic.

This has all been made worse, one suspects, by the effects of the pandemic-induced lifestyle changes — consequences of the forced isolation that changed social and work practices in ways that haven’t changed back.

Other changes have been coming slowly over the decades, but all add to the lonely life. The way of life has had a trajectory for those who live alone, which has increased the possibility of loneliness.

We isolate ourselves in ways that are new or only decades old. We drive alone. We live in a house or apartment, if single, alone. We work alone in that dwelling, facing a computer or watching a movie on television alone.

I call this the box culture: We drive in a box, live in a box, and, as likely as not, stare into a box as we work.

Changing work patterns are probably a critical part of the structural loneliness that is now rampant. Even if one doesn’t work at home, we work differently. We used to make contacts, and often new friends, by doing business on the telephone. Now we shoot off an email and maybe, if it can’t be avoided, make an appointment to make a video call with several people.

We have wrung out all spontaneity. Making friends is a kind of spontaneous combustion. You might as well be doing business with AI for all the lack of warmth or humor in today’s work interactions.

Then there are work friends. For most of us, it was at work or through work that we made our friends — that is, if they weren’t carryovers from school or college.

People who work together and play together fall in love, sometimes get married, and sometimes meet a friend who undoes a marriage. There is a lot of sex at places of work, although companies might deny it. Note the number of CEOs who marry their assistants.

Another feature of the loneliness structure is that pub life is in decline. The local tavern, even for non-drinkers, was part of the way we lived, and drinking isn’t as pervasive as it once was.

Time was when after work or wishing to see a friend, you went for drinks. People gave drinks parties at noon on weekends: no food, just a convivial glass. That isn’t extinct, but it isn’t what it used to be.

Drinking oils society’s wheels but of course too much, and the wheels come off. Go sit at the bar, and someone will talk to you. There is camaraderie in a saloon.

Entertaining has become more formal. Blame all those cooking shows on television. People don’t have friends over for a hamburger anymore. No. They have to have Steak Diane and a soufflé — a meal with the stamp of Julia Child on it. Result: less dropping in on friends, more isolation.

Of course, there are those who are lonely because of bereavement, sickness, old age and family abandonment. But those things have always been with us. They really suffer loneliness, feel the terrible blanket of isolation.

For those who have decided it is too strenuous to go to the office, that the phone is for messaging, that home loneliness is inevitable because we can’t cook or are ashamed of our homes, join something: a church, a theater group, a book club or do volunteer work.

Much of loneliness, from what I can divine, is a product of how we live now. We sit in our boxes inadvertently avoiding others. Television isn’t friendship, drinking alone isn’t companionship. Go shopping in a store, go to church, go to the pub, work in the food bank, join a book club. As the old AT&T advertisement used to say, “Reach out and touch someone.”

No one can predict how or where great friends or great loves will be found, but certainly not staring at a computer.

Several of my greatest friendships are a result of people who have taken violent exception to something I have written and wanted to meet up to berate me. The facts were wrong. I was evil, I met them to take my medicine, as it were, and parted knowing a new friend.

Surgeon Gen. Vivek Murthy has raised the issue of loneliness. He would be advised to tell people to look at lifestyle. Does it have loneliness baked in?

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Llewellyn King: Despair and danger

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Body language is the new political voice in America.

The language is universal and easily learned because it has just four components: eye-rolling, sighing and shrugging, accompanied by turning hands up.

“Oh my God, it’s a disaster,” is one translation. Another might be, “Don’t ask me, I didn’t sign on for this.”

It belongs — this silent expression of despair about the presidential election, unfolding for 2024 — to old-line Republicans and to a wide swath of Democrats, too.

Political discussion has ended in these groups, replaced by the kind of fatalism summed up in the words of the Irish poet William Butler Yeats that we are slouching toward Bethlehem.

Of course, as Washington Post columnist George Will says, the inevitable isn’t necessarily inevitable. However, at the moment, it looks as if it is.

The despair is spread pretty evenly among Democrat, many of whom consider President Biden too old, and Vice President Kamala Harris not up to the job she has, let alone the presidency.

At 80, Biden is showing reduced vigor and limited mobility, and he favors scripted speeches. This from a politician who was famous for nonstop talking.

Over the years, like other reporters, I have often thought, “Joe, you have made your point, now stop.” These days, you wait in vain for him to go off script. His speeches, which he reads from a Teleprompter, sound as though they were prepared by a committee — lifeless repetition.

He never holds a press conference, a sign of dwindling confidence.

The bigger fear in the Democrats isn’t that Biden is too old but that Harris, at some point, may become president. She has proven herself to be woefully inept and incoherent.

In every assignment Biden has handed her on which she could have shown her worth, she has failed or simply not done. Remember, she was Biden’s point person on the border crisis? She hasn’t been heard from as such.

This past spring, she went to Ghana, Tanzania and Zambia to counter the Chinese and chose to make it an occasion to apologize for slavery. I was born and raised in Africa, in what is now called Zimbabwe, and have traveled extensively on the continent, and slavery isn’t a burning issue. The high point of this visit was Zambia, where Harris’s paternal grandfather came from and where she was welcomed.

China has three great appeals to African countries: It asks no questions, doesn’t lecture on human rights, and pays off the ruling elites, trading these indulgences for minerals.

While Biden and Harris may seem a dangerous pair, Donald Trump, twice indicted (so far), twice impeached, now reduced to feeling sorry for himself on a colossal scale, is terrifying. He has promised an administration of vengeance.

Whereas I can’t find any Democrats who are enthusiastic about the Biden-Harris ticket, I certainly can find far-right Republicans who love Trump. Mostly, they are the working-class White voters, who were once the mainstay of the Democratic Party and now believe that the America they know and want to preserve can only be saved by the reprehensible Trump, with his relentless abuse of all who cross him and endless lachrymose pity for himself.

Trump’s defense of himself is risible, but the faithful Trumpsters believe in him — as much as ever.

They aren’t statistics to me. Recently, my wife and I were eating at a Chinese restaurant in Rhode Island when a couple with a small child took the booth behind us. You might call them the salt of the earth: working people doing their best to raise a family. The husband was complaining loudly about the high cost of living. Then, after seeing Trump on an overhead TV, he said to his wife, “The only honest man is Trump.”

That young father wasn’t alone.

At a neighborhood pub that, in the British sense, is our “local,” the owner and patrons know that both my wife and I are journalists, and because Rhode Island PBS airs our program, White House Chronicle, we are treated with deference. But that doesn’t prevent good, hard-working, fellow patrons, mostly of Italian, Irish and Portuguese stock, from lambasting the media within earshot of us. “It’s all lies.” “They hate Trump because he tells the truth.” They say things like that because they believe them. They are the Trump base.

When I hear that stuff, how do I react? Well, I roll my eyes, sigh, shrug my shoulders, and, if no one is looking, I turn my hands up to the heavens.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Llewellyn King: U.S. politicians are so bad because the campaign process has become so ghastly

“The Demagogue,’’ by Jose Orozco

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I am often asked why in a country of such talent and imagination the U.S. political class is so feeble. Why are our politicians so uninspiring, to say nothing of ignorant and oafish.

The short answer is because political life is awful and potential candidates have to weigh the impact on their families, plus the wear and tear of becoming a candidate, let alone winning.

I would name three barriers that keep good people out of politics: the money, the primary system and the media scrutiny.

Taking these in order, you must have access to enormous funding to be a candidate. Jefferson Smith, the character in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, the 1939 movie starring James Stewart, was appointed to a Senate seat. He didn’t have to subject his rectitude to the electoral process.

A candidate for Congress must get substantial funding from the outset and be prepared to spend much of his or her career raising money, which frequently means bending your judgment to the will of donors. Yes, Mr. Smith, to some extent the system is inherently corrupt.

I asked a major political consultant what he asks a candidate before going to work for him or her. First is money: Do you have your own or can you raise it? Second is skeletons in the closet: Have you been arrested for indecent exposure, drunk-driving or other offenses?

Finally, the consultant told me, he asks a candidate: What do you stand for. In short, the mechanisms of politics trump principle. A member of the House once told me that he spent much of his time meeting with donors and attending fundraisers. “You’ve got to do it,” he said.

In the days of the smoke-filled rooms – there really was a lot of smoke -- the party, the professionals, prevailed. In the primary-based system, the odds are on those who are extreme and appeal to the fringes of their party ideology. The party doesn’t shape today’s candidates, they shape the party.

Massachusetts Gov. and then U.S. Sen. Leverett Saltonstall (1892-1979), a classic moderate New England Republican, nicknamed “Salty.’’

Look at the Republicans, little recognizable from the party of old; the party which was held in check by moderate New England stalwarts. Or look at the way the Democrats fight to avoid falling into the chasm of the far left. Once the Democrats were held in check by labor, which gave the party an institutional center.

On the face of it, the primary system favors grassroots democracy and the individual. In fact, it favors those with rich friends, who will cough up.

Finally, there is the media scrutiny. If you want to run for office, you become a public plaything. Everything you ever wrote or said can and will be dredged up. Opposition-research operatives will interview old lovers; check on what you wrote in the school yearbook; rake through your social-media posts, and look for that unfortunate slip of the tongue in a local television interview years ago will be reprised on the evening news. You have a target on your back, and it will be there every day you are in office.

This delving into every corner of a life is a huge barrier that keeps a lot of talent out of politics. Anyone who has ever had a disputed business dealing, a DUI arrest (not even a conviction) or a messy divorce is advised to forego a political career, no matter how talented and how much real expertise Mr. Smith might bring to the state house or Congress.

Run for political office and you put your family at risk, your private life on display and, having been hung out to dry, you may not even win.

These are some of the factors that might explain why the Congress is so risible and why such outrageously fringy people now occupy high office.

Having observed politics on three continents, I firmly believe that it needs strong institutions in the form of local political associations and party structure, and that candidates should be judged on the body of their work, not on a slip of the tongue or an indiscretion.

However, the selection of candidates is always a hard call. If parties have too much control over the system, party hacks are favored and new, quality candidates are shut out.

If primaries continue as they have, the fringes triumph. Just look at the Congress — a smorgasbord of wackiness.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: We get bad politicians because running for office has become so ghastly

“The Demagogue,’’ by Jose Clemente Orozco

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I am often asked why in a country of such talent and imagination the U.S. political class is so feeble. Why are our politicians so uninspiring, to say nothing of ignorant and oafish.

The short answer is because political life is awful and potential candidates have to weigh the impact on their families, plus the wear and tear of becoming a candidate, let alone winning.

I would name three barriers that keep good people out of politics: the money, the primary system and the media scrutiny.

Taking these in order, you must have access to enormous funding to be a candidate. Jefferson Smith, the character in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, the 1939 movie starring James Stewart, was appointed to a Senate seat. He didn’t have to subject his rectitude to the electoral process.

A candidate for Congress must get substantial funding from the outset and be prepared to spend much of his or her career raising money, which frequently means bending your judgment to the will of donors. Yes, Mr. Smith, to some extent the system is inherently corrupt.

I asked a major political consultant what he asks a candidate before going to work for him or her. First is money: Do you have your own or can you raise it? Second is skeletons in the closet: Have you been arrested for indecent exposure, drunk-driving or other offenses?

Finally, the consultant told me, he asks a candidate: What do you stand for. In short, the mechanisms of politics trump principle. A member of the House once told me that he spent much of his time meeting with donors and attending fundraisers. “You’ve got to do it,” he said.

In the days of the smoke-filled rooms – there really was a lot of smoke -- the party, the professionals, prevailed. In the primary-based system, the odds are on those who are extreme and appeal to the fringes of their party ideology. The party doesn’t shape today’s candidates, they shape the party.

Look at the Republicans, little recognizable from the party of old; the party which was held in check by moderate New England stalwarts. Or look at the way the Democrats fight to avoid falling into the chasm of the far left. Once the Democrats were held in check by labor, which gave the party an institutional center.

On the face of it, the primary system favors grassroots democracy and the individual. In fact, it favors those with rich friends, who will cough up.

Finally, there is the media scrutiny. If you want to run for office, you become a public plaything. Everything you ever wrote or said can and will be dredged up. Opposition-research operatives will interview old lovers; check on what you wrote in the school yearbook; rake through your social-media posts, and look for that unfortunate slip of the tongue in a local television interview years ago will be reprised on the evening news. You have a target on your back, and it will be there every day you are in office.

This delving into every corner of a life is a huge barrier that keeps a lot of talent out of politics. Anyone who has ever had a disputed business dealing, a DUI arrest (not even a conviction) or a messy divorce is advised to forego a political career, no matter how talented and how much real expertise Mr. Smith might bring to the state house or Congress.

Run for political office and you put your family at risk, your private life on display and, having been hung out to dry, you may not even win.

These are some of the factors that might explain why the Congress is so risible and why such outrageously fringy people now occupy high office.

Having observed politics on three continents, I firmly believe that it needs strong institutions in the form of local political associations and party structure, and that candidates should be judged on the body of their work, not on a slip of the tongue or an indiscretion.

However, the selection of candidates is always a hard call. If parties have too much control over the system, party hacks are favored and new, quality candidates are shut out.

If primaries continue as they have, the fringes triumph. Just look at the Congress — a smorgasbord of wackiness.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Yes. climate change is upon us, but panic isn’t a tool against it

The Kendall Cogeneration Station, in Cambridge, Mass., is a natural-gas- powered station owned by Vicinity Energy that produces both steam and electricity for Boston and Cambridge. We’ll be hooked on natural gas for a long time to come.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

One of the luxuries of democracy is that we don’t have to listen. Or we can listen and hear what we want to hear. We can find resonance in dissonance, or we can hear flat notes.

That is the story of the climate crisis, which is here.

We have been warned over and over, sometimes as gently as a summer zephyr, and sometimes gustily, as with Al Gore’s tireless campaigning and his seminal 1992 book, and later movie, Earth in the Balance.

Now high summer is upon us — with its intimations of worse to come. And this message rings in our ears: The climate is changing — polar ice caps are melting; the sea level is rising; the oceans are heating up; natural patterns are changing, whether it be for sharks or butterflies; and we are going to have to live with a world that we, in some measure, have thrown out of kilter.

Around the beginning of the 20th Century, we began an attack on the environment, the likes of which all of history hadn’t seen, including two centuries of industrial revolution. Sadly, it was when invention began improving the lives of millions of people.

Two big forces were unleashed in the early 20th Century: the harnessing of electricity and the perfection of the internal-combustion engine. These improved life immensely, but there was a downside: They brought with them air pollution and, at the time unknown, started the greenhouse effect.

In the same wave of inventions, we pushed back the ravages of infectious diseases, boosted irrigated farming and enabled huge growth in the world population — all of whom aspired to a better life with electricity and cars.

In 1900, the world population was 1.6 billion. Now it is 8 billion. The population of India alone has increased by about a billion since the British withdrawal, in 1947. Most Indians don’t have cars, jet off for their vacations or have enough, or any, electricity, and very few have air conditioning. Obviously, they are aspirational, as are the 1.4 billion people of Africa, most of whom have nothing. But the population of Africa is set to double in 25 years.

The greenhouse effect has been known and argued about for a long time. Starting in 1970, I became aware of it as I started covering energy intensively. I have sat through climate sessions at places like the Aspen Institute, Harvard and MIT, where it was a topic and where the sources of the numbers were discussed, debated, questioned and analyzed.

Oddly, the environmental movement didn’t take up the cause then. It was engaged in a battle to the death with nuclear power. To prosecute its war on nuclear, it had to advocate something else, and that something else was coal: coal in a form of advanced boilers, but nonetheless coal.

The Arab oil embargo of 1973 added to the move to coal. At that point, there was little else, and coal was held out as our almost inexhaustible energy source: coal to liquid, coal to gas, coal in direct combustion. Very quiet voices on the effects of burning so much coal had no hearing. It was a desperate time needing desperate measures.

Natural gas was assumed to be a depleted resource (fracking wasn’t perfected); wind was a scheme, as today’s turbines, relying heavily on rare earths, hadn’t been created, nor had the solar electric cell. So, the air took a shellacking.

To its credit, the Biden administration has been cognizant of the building crisis. With three acts of Congress, it is trying to tackle the problem — albeit in a somewhat incoherent way.

Some of its plans just aren’t going to work. It is pushing so hard against the least troublesome fossil fuel, natural gas, that it might destabilize the whole electric system. The administration has set a goal that by 2050 — just 27 years from now — power production should produce no greenhouse gases whatsoever, known as net-zero.

To reach this goal, the Environmental Protection Agency is proposing strict new standards. However, these call for the deployment of carbon capture technology which, as Jim Matheson, CEO of the Rural Electric Cooperative Association, told a United States Energy Association press briefing, doesn’t exist.

The crisis needs addressing, but panic isn’t a tool. A mad attack on electric utilities, the demonizing of cars or air carriers, or less environmentally aware countries won’t carry us forward.

Awareness and technology are the tools that will turn the tide of climate change and its threat to everything. It took a century to get here, and it may take that long to get back.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and is based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Llewellyn King: What happened to the kingmakers of journalism?

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

What happened to the kingmakers of journalism?

They seem to have died in 2011 with David Broder, of The Washington Post. In an age when columnists could still influence the flow of events, Broder stood out as much for what he wasn’t as for what he was.

He wasn’t, for example, a flashy writer. He didn’t have George Will’s turn of phrase. He didn’t add to the language like another kingmaker a generation before him, Walter Lippmann. Lippmann gave us “Great Society,” “Cold War” and “stereotype.”

What set Broder apart was the depth of his political reporting.

I worked with Broder at The Post, and he was relentless. If you were into politics, you were grist to his mill. From precinct captains to senators, they were all of interest to Broder, all worthy of his probing; all had a tale to tell, and Broder wanted to hear it.

Journalists at The Post used to drink in a genuinely downmarket bar called The New York Lounge, next to the better-known Post Pub, which, ironically, was eschewed by most of the editorial staff. Incongruously, Broder would be found there occasionally with some political apparatchik, notebook out and drinking a Diet Coke.

A reporter who traveled with Broder described how when they arrived in Midwestern city at 10 p.m., Broder got on the phone to see who of the local political establishment was up. It could have been a candidate or the local state party chairman; all were worth talking to in Broder’s world.

Whereas some newspaper grandees talked to presidents and the power elite (Lippmann helped Woodrow Wilson write his Fourteen Points, Joe Alsop shared sessions with Lyndon Johnson on the Vietnam War, and George Will rehearsed Ronald Reagan for his debates with Jimmy Carter), Broder reported relentlessly at all levels.

For all but the very end of his career, Broder worked as a reporter who wrote two columns a week. This industrious reporting underpinned the columns. They were magisterial and analytical.

You didn’t pick them up to be entertained but to get insight. That is where Broder’s strength lay, and that is what made him a kingmaker. Other political journalists and writers read Broder and were informed by him.

He told them which way the wind was blowing, and that filled their sails and influenced their work. Broder informed the political universe.

That is how he affected the careers of many a political grandee. He said in his studious and understated way, “Look at so-and-so.” And they looked, and then they wrote, and the landscape was changed.

I recall vividly a lunch at the Financial Times headquarters in London in 1975. Apart from FT people who included, as I recall, David Fishlock, the science editor, there was Virginia Hamill from The Washington Post News Service and Bernard Ingham, who was to become Margaret Thatcher’s press secretary.

The talk was about who would win the Democratic nomination. I had flown in from Washington the day before and had read Broder in The Post, so I blurted out, “Jimmy Carter.” The group looked askance and wanted to know why I had such a crazy idea. I replied, “Because Broder has discovered him.”

Broder’s influence was subtle but pervasive. He was the reporter’s reporter, the columnist’s columnist.

In the time since Broder’s death, everything has changed. There is so much commentary based on little reporting and politics is dominated by click-bait politicians — for example, Donald Trump, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert.

Analysis has been replaced with tribal bellowing, and social media has taken the debate off the editorial pages and handed it to influencers, who wouldn’t have gotten a letter to the editor published before the internet.

While dwelling on the kingmakers of old, it is worth mentioning the king-humblers, particularly Robert Novak. Novak got the goods.

Again, Novak wasn’t a great writer but was the source of hard gossip. If you wanted to point to wrongdoing in high places, a call to Novak would set the wheels of justice, or at least the downfall would be in motion.

Novak, a friend, thought that you should tell readers what they didn’t already know — and he did, often changing career trajectories for politicos.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

History of India in New England; Llewellyn King on what holds back that huge nation

Sri Lakshmi {Hindu} Temple, in Ashland, Mass.

— Photo by Tshiv

From “The Indian Presence in New England: People and Ideas” . Hit this link to read the whole article.

“There were some exceptions to this general atmosphere of non-acceptance {of Indians in America}. In general, the intellectuals of the Northeast were not active participants in such overt racialized discourse. Jane Jensen states that New England intellectuals developed a deep interest in Indian religions in the early 19th century, at about the time the New England-India trade developed. She describes how Boston society became interested in Indian literature and in Indian religions, especially Hinduism, Buddhism and the Brahmo Samaj movement. Intellectuals at universities such as Harvard began to cultivate an active scholarship and also initiated a nascent Indian art collection at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. The theosophical writing of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, as well as Walt Whitman’s poems (such as “Passage to India” and “Leaves of Grass”), are reflective of this trend. These earlier writings of the Transcendentalists, on the “life of the spirit” (developed on the basis of an earlier encounters with Hinduism), prepared the ground for Vivekananda and his message.’’

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi

By Llewellyn King

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

By the diplomatic hoopla in Washington that greeted Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi last week, it would seem that intrepid U.S. explorers had just discovered India and were celebrating him in the way Britain treated tribal leaders in the 19th Century: Show them the big time. Then co-opt them to vow allegiance.

In this century, the U.S. equivalent of the big time is a state visit and endless professions of friendship. Experience says Modi won’t bite.

Historically, India has been reluctant to accept the embrace of the West. Although it is democratic, capitalist and has the largest diaspora, India’s affections have been hard to capture.

Since independence from Britain in 1947, India has sought global status by standing aloof and leaning toward countries and regimes that are anathema to the West. Its first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, fostered the concept of a third force in the world: a constellation of unaligned nations with India at the center.

It showed a perverse affection for the Soviet Union — which was hardly nonaligned — and didn’t reflect the values of India: free movement of people, free press, capitalism and democracy.

Years ago, a retired executive editor of the Times of India, whom I knew socially, told me, “There are maybe a million Indians living in the United States and only a handful who live in the Soviet Union, but our leaders have always leaned toward them. It is a puzzle.”

There are now 4.2 million Indians living in the United States.

At the same time, Indians migrated across the world and made inroads into professions from Canada to New Zealand. In Britain, they are prominent in politics and the prime minister, Rishi Sunak, is of Indian descent.

In the United States, executives of Indian descent run some of the largest tech companies, including IBM, Google and Microsoft.

Indians are a huge force in English literature. Every year Indian writers feature on the prize lists for best new English novels. Whereas the computers most of us use may have been made in China, much of the software was written in India.

Indian words abound in English: Pajamas, ketchup, bungalow, jungle, avatar, verandah, juggernaut and cot are just a few.

The effect of Indian culture on the world is evident from curry and rice to polo to yoga.

Yet, India remains a distant shore, elusive and obvious at the same time. A country of enormous talent that lags economically. It now has the fifth-largest economy in the world. With 1.4 billion people, many of whom of obvious ability, the question must be, why does it still have crushing poverty?

Andres Carvallo, professor of innovation at Texas State University, told the “Digital 360” webinar, for which I am a regular panelist, he thought it was partly because India lagged in essential electricity production, pointing out that China has four times the electricity output of India.

But is this symptom or cause? I have been puzzling over why India doesn’t do better for decades. It seems to me that the causes are multiple, but some can be laid at Britain’s feet — not because the British were occupiers in India but because of some of the good things they left there that have perversely remained time-warped.

One of India’s ambassadors to Washington told me with pride that every occupier had enriched India and left something of value behind, from Alexander the Great to the Moguls and, of course, Britain and the Raj.

But the Brits also left behind a sluggish bureaucracy to the point of sclerosis and a legal system that is independent but takes an eternity to reach a decision. Additionally, some of the ideas prevalent in British Labor Party thinking — and long since abandoned — took hold in India and have been extremely detrimental. These included protectionism, a state’s role in the economy, and a fear of competition from abroad.

I believe that protectionism is the greatest evil. It discouraged competition, innovation and creativity. It inadvertently allowed a few families to concentrate too much wealth and economic power and to work to protect that.

India is more open now, but it needs to be vigilant against the evils that go with protectionism, which is still part of its DNA.

At one time, you could buy a brand-new Indian made-car — Fiat or Morris design — which was 30 years out of date. No need to innovate; just make the same car year after year.

If it liberalizes its economy, India may one day outpace China. Meantime, do luxuriate in those Indian words that have so spiced up English.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Watch or Listen to White House Chronicle

Streaming: All episodes are free to watch on Vimeo [link]

On television: Visit our website [link] to find your location carrying station.

SiriusXM radio: Listen to White House Chronicle on P.O.T.U.S., Channel 124: Saturday at 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. ET; and Sunday at 4 p.m. and 11 p.m. ET.

#India

#White House Chronicle

Llewellyn King: Smoke spreads amidst global warming but beware overzealous regulation

Smoke from Canadian forest fires in the Delaware River Valley. See New England’s “Dark Day’’.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The smoke from wildfires in Canada that has been blown down to the United States, choking New York City and Philadelphia with their worst air quality in history and blanketing much of the East Coast and the Midwest, may be a harbinger for a long, hot, difficult summer across America.

It could easily be the summer when the environmental crisis, so easily dismissed as a preoccupation of “woke’’ Greens and the Biden administration, moves to center stage. It could be when America, in a sense, takes fright. When we realize that global warming is not a will-or-won’t-it-happen issue like Y2K at the turn of the century.

Instead, it is here and now, and it will almost immediately start dictating living and working patterns.

In an extraordinary move, Arizona has limited the growth in some subdivisions in Phoenix. The problem: not enough water. Not just now but going forward.

The floods and the refreshing of surface impoundments, such as Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the nation’s largest reservoirs, haven’t solved the crisis.

All along the flow of the Colorado River, aquifers remain seriously depleted. One good, rainy season, one good snowpack may recharge a dam, but it doesn’t replenish the aquifers that hydrologists say have been undergoing systematic depletion for years.

An aquifer isn’t just an underground river that runs normally after rainfall. It takes years to recharge these great groundwater systems. These have been paying the price of overuse for years; across Texas and all the way to the Imperial Valley, in California, unseen damage has been done.

It isn’t just water that looms as a crisis for much of the nation, there is also the sheer unpredictably of the weather.

I talk regularly with electric- and gas-utility company executives. When I ask them what keeps them awake at night, they used to respond, “Cybersecurity.” Recently, they have said, “The weather.”

This year, we are entering the tropical-storm season with unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Atlantic and the Pacific. The doleful conclusion is that these will signal severe and very damaging weather activity across the country.

The utilities have been hardening their systems, but electricity is uniquely affected by weather. The dangers for the electricity industry are multiple and all affect their customers. Too much heat and the air-conditioning load gets too high. Too much wind and power lines come down. Too much rain and substations flood, poles snap and there is crisis, from a neighborhood to a region.

In the electricity world, the words of John Donne, the 16th-Century English metaphysical poet, apply, “No man is an island entire of itself.”

There is another threat that the electricity-supply system will face this summer if the weather is chaotic: overzealous politics and regulation.

It is the electric utilities that are most identified in the public mind with climate change. The public discounts the myriad industrial processes as well as the cars, trucks, bulldozers, trains and ships that lead to the discharge of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Instead, it is utilities that have a target pinned to them.

A bad summer will lead to bad regulatory and bad political decisions regarding utilities.

Foremost are likely to be new attacks on natural gas and its supply chain, from the well, through the pipes, into the compressed storage, and ultimately to combustion turbines.

At this time, natural gas – about 60-percent cleaner than coal — is vital to keeping the lights on and the nation running when the wind isn’t blowing, or the sun has set or is obscured.

The energy crisis that broke out in the fall of 1973, and lasted pretty well to the mid-1980s, was characterized by silly over-reactions. First among these was probably the Fuel Use Act of 1978, which got rid of pitot lights on gas stoves and even threatened the eternal flame at Arlington Cemetery.

It also accelerated the flight to coal because, extraordinarily, that was the time of the greatest opposition to nuclear power — from the environmental communities.

This summer may be a wakeup for climate change and how we husband our resources. But wild overreaction won’t quiet the weather.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and a long-time editor, writer and consultant in the international energy sector. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

#global warming #Llewellyn King #electric utilities

Llewellyn King: ‘Thank you for wearing a bow tie,’ they say

Llewellyn King

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

From time to time, I feel it necessary to report on the necktie wars. Sadly, the news is dismal. Neckties are in retreat, and in many instances, they have disappeared.

Father’s Day this month is already causing stress. The rule was always when in doubt, give a necktie. Certain to please.

But if you give the old boy a necktie this year, you know it will never see the light of day after the insincere raving about how lovely it is.

The next several weeks will see children hopelessly crowding men’s haberdashers, seeking that sure-to-please gift.

I predict that men who have never stuck anything so much as a ticket in the upper left pocket will be inundated with pocket squares. Before pocket squares were what they have shrunk to, they were full-size handkerchiefs, albeit of silk or something that looked like silk.