‘Contemplation and curiosity’

Work by Japanese-American and Boston-based artist Yuko Oda, in her show “Entering, Arriving, Departing, at Boston Sculptors Gallery, Aug. 30-Oct. 1.

The gallery says:

“Yuko Oda’s personal history involves lifelong pilgrimages to her homeland of Japan. On a recent trip she visited several shrines and temples, walking through numerous gates and performing rituals such as ringing bells to pay respect and purifying oneself with water. Oda also recently experienced a loss in her family. These events coalesced into the creation of ‘Arriving, Entering, Departing,’ an immersive installation where visitors are invited to remove their shoes, enter, and experience a place of contemplation, curiosity, and wonder.’’

Return to putting up with it

Inside Boston’s famed Symphony Hall during a concert

“Tonight I will speak up and interrupt

your letters, warning you that wars are coming,

that the Count will die, that you will accept

your America back to live like a prim thing

on the farm in Maine.

I tell you, you will come

here, to the suburbs of Boston, to see the blue-nose

world go drunk each night, to see the handsome

children jitterbug, to feel your left ear close

one Friday at Symphony.’’

— From “Some Foreign Letters,’’ by Anne Sexton (1928-1974), Pulitzer Prize-winning Massachusetts poet

Boston-based Verve Therapeutics partners with Lilly to target cholesterol

Edited from a New England Council report:

“Eli Lilly is collaborating with Boston-based Verve Therapeutics on a gene-editing program with a total value of $525 million. Eli Lilly will pay $60 million to use Verve’s gene-editing technology to target a cholesterol-carrying protein. The agreement also includes potential milestone payments of up to $465 million, as well as royalties for Verve. Verve plans to test Phase 1 clinical trials, with Eli Lilly handling clinical development, manufacturing, and commercialization.

“Verve Therapeutics, which focuses on eliminating cardiovascular disease associated with high cholesterol, emerged in 2019 with technology developed by Harvard scientists. The company went public in 2021 and has received investments from GV, Wellington Management Company, and Casdin Capital, as well as collaboration deals with Beam Therapeutics and Verily. Following the announcement of the collaboration, Verve’s shares rose more than 12 percent.’’

David Warsh: AI firms and news publishers are dickering over revenue sharing

Baker Library at Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College’s Kiewit Computation Center, cutting edge when it was built, in 1966, and torn down as outdated, in 2018

From Cantor’s Paradise:

“The Dartmouth (College) Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence was a summer workshop widely considered to be the founding moment of artificial intelligence as a field of research. Held for eight weeks in Hanover, New Hampshire in 1956 the conference gathered 20 of the brightest minds in computer- and cognitive science for a workshop dedicated to the conjecture:

"..that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves. We think that a significant advance can be made in one or more of these problems if a carefully selected group of scientists work on it together for a summer."

-- A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (McCarthy et al., 1955)

Somerville, Mass.

Why the speed with which artificial intelligence technologies have been sprung on the world? The answer may have something to do with the model that AI companies have in mind for the most potentially lucrative among their new businesses. Once again it seems to have to do mostly with advertising.

As a result, the newspaper business, broadly defined to include data-base/software businesses such Bloomberg, Reuters and Adobe, is taking stock of itself and its prospects as never before. Readers are learning about the capabilities and limitations of generative artificial intelligence engines, which can produce on demand Wiki-like articles containing detailed but not necessarily dependable information. In the bargain, we may even learn something important about the systems of industrial standards that govern much of our lives.

Those implications emerged from a Financial Times story other week that Google, Microsoft, Adobe and several other AI developers have been meeting with news company executives in recent months to discuss copyright issues involving their AI products, such as search engines, chatbots and image generators, according to several people familiar with the talks.

FT sources said that publishers including News Corp, Axel Springer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and The Guardian have each been in discussions with at least one major tech company. Negotiations remain in their early stages, those involved in them told the FT. Details remain hazy: annual subscriptions ranging from $5 million to $20 million have been discussed, one publisher said.

This much is already clear: Media companies are seeking to avoid compounding the mistakes that allowed Google and Facebook to take over from print, broadcast and cable concerns the lion’s share of the advertising business, in a wave of disruption that began around the start of the 21st Century.

A major problem involves avoiding further concentration among media goliaths. At stake is the privilege of decentralized newspapers, competing among themselves, to remain arbiters of democracies’ provisional truth, the best that can be arrived at quickly, day after day.

Mathais Döpfner. whose Berlin-based media company owns the German tabloid Bild and the broadsheet Die Welt, told FT reporters that an annual agreement for unlimited use of a media company’s content would be a “second best option,” because small regional or local news outlets would find it harder to benefit under such terms. “We need an industry-wide solution,” Döpfner said. “We have to work together on this.”

The background against which such discussions take place is copyright law. Obscured is the role frequently played by privately negotiated industry standards.

Behind the scenes talks will continue. But the changing nature of advertising-based search is a breaking story. Newspapers remain free to take their case to the public, in hopes of government intervention of unspecified sorts.

The adage applies about lessons learned from experience: fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

#David Warsh

#artificial intelligence

Just get us there

“‘We don’t want rapists or sexual deviants driving cabs,’ an official of the City of Boston Cab Association was once quoted as declaring. However, most Bostonians would gladly travel to their destinations with a sexual deviant if only said driver could be counted upon to know the way.’’

— Nathan Cobb, in “Taxing Toward a Fun City,’’ from CITYSIDE/COUNTRYSIDE, by Mr. Cobb and John N. Cole (1980)

Maybe don’t go any further

Photo by Massachusetts-based artist Chantal Zakari, in her show “Chantal Zakari: New Works,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Aug. 30-Oct. 1

She says:

“I am inspired by social phenomena and position myself in relation to the public. I freely combine research methodologies and artistic strategies from various disciplines such as photography, documentary, graphic design, performance, storytelling, installation, and social interventions. Text and language are an inherent part of my work; interviews, personal narrative, found text, all have the potential to contextualize the imagery. My work is project based. As I explore projects over the span of several years, the work can transform into exhibitions, installations, publications, performances and street happenings. Designing and redesigning the work into different contexts brings me a greater understanding of the ideas, and makes it more accessible to different groups of audiences.”

'Though his pass is middle-class'

James Michael Curley in 1949, in his final term as Boston mayor

Principal streets of the Back Bay, an affluent part of Boston

“I enjoy a tender pass

By the boss of Boston, Mass.,

Though his pass is middle-class

And not Back Bay

But I'm always true to you, darlin', in my fashion

Yes, I'm always true to you, darlin', in my way.’’

— From the song “Always True to You in My Fashion,’’ by Cole Porter, in the 1948 musical Kiss Me, Kate. The “boss” referred to was apparently the colorful and corrupt Mayor James Michael Curley (1874-1958).

The architecture of language

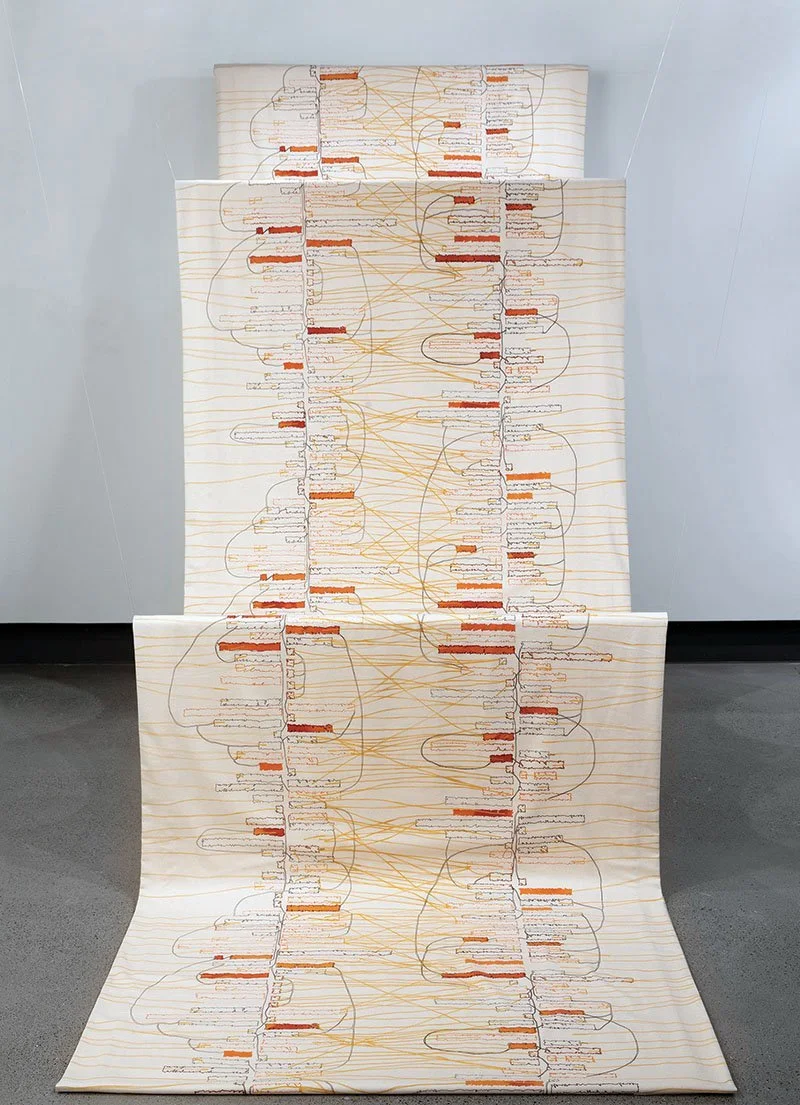

From Massachusetts artist Sarah Hulsey’s show “Source Material,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through July 2

She says:

“My work is concerned with the architecture that underpins language, which we use effortlessly but with little awareness of its beauty and complexity. Even a simple sentence has layers and layers of organization, governed by a complex set of rules and interactions happening below the level of our conscious knowledge. Small pieces of information (atomic components, as it were) combine into ever larger units within the concurrent linguistic systems at play. These components are organized into elegant structures that exist only in the mind. In my artwork, I analyze these structures and create visual correlates, looking for poetry and resonance in the rich patterns that emerge. ‘‘

I compose abstract frameworks by building up nested and connected forms set within reticulated grids. Networks of these grids serve as armatures on which small elements abut, merge, and grow into higher order objects. In these pages, the underlying structures of sentences are segmented, excerpted, and then recombined into forms reflecting their core, essential relationships.

Going Dutch

Downtown Boston

— Photo by Nick Allen

Adapted from From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

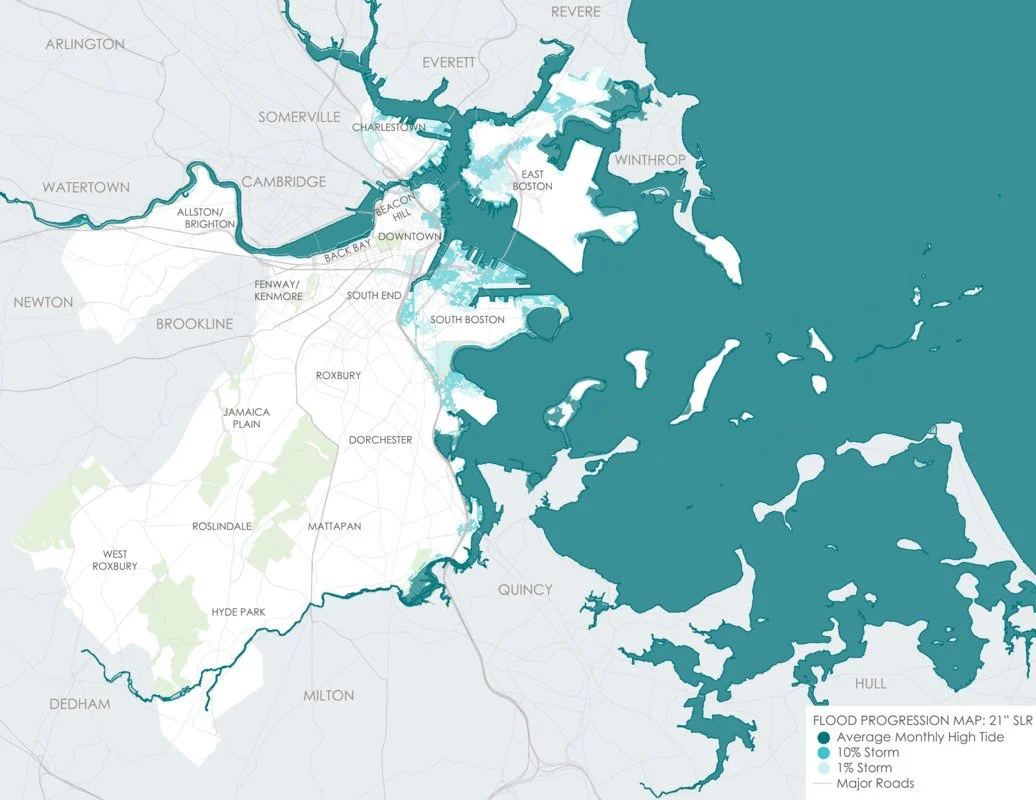

A consulting firm’s study recommends that a huge, $877 million flood barrier be built to protect downtown Boston from the increased coastal flooding associated with global warming. Of course, there would be big cost overruns in something as complicated as this project; it would probably cost several billion.

Meanwhile, Boston can stock up on lifeboats, wetsuits and swimming lessons. But sadly the threat is too episodic for gondolas.

Boston bummer

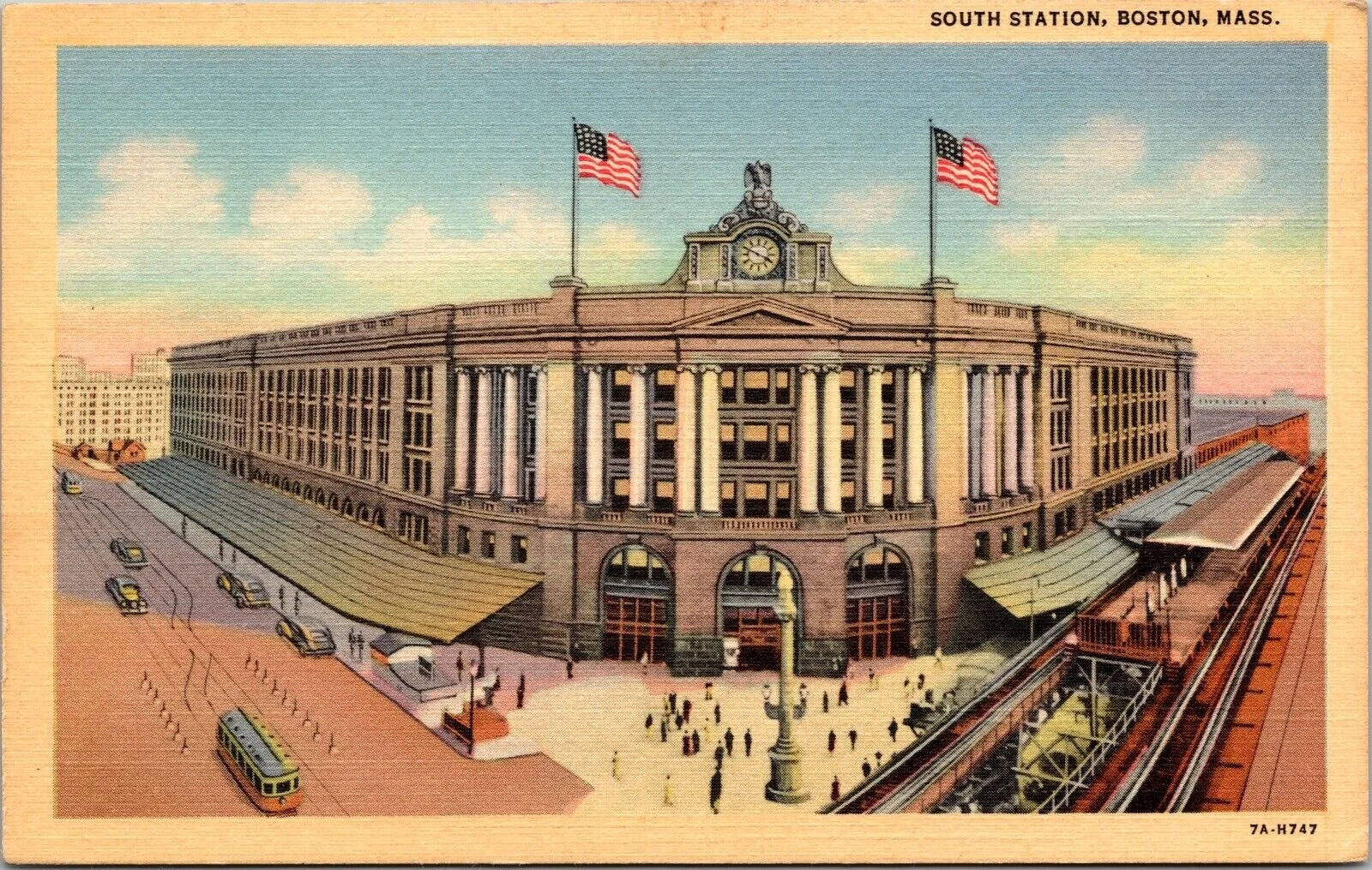

Boston’s South Station in the Thirties

“I have just returned from Boston. It’s the only sane thing to do if you find yourself up there.’’

xxx

“There was a rumor that {Boston} Mayor {John F.} Fitzgerald {maternal grandfather of President John F. Kennedy} had sung ‘Sweet Adeline’ in office for so many years that the City Hall acoustics had diabetes.’’

— Fred Allen (whose birth name was John Florence Sullivan) (1894-1956), in a June 1953 letter to Groucho Marx (1890-1977). Allen was raised in Boston and became a star comedian of “The Golden Age of Radio’’.

#Fred Allen

#Boston

Mommy dearest?

“Urban Toile” (relief cut), by Boston artist Ellen Shattuck Pierce, in the group show “Oh, Mother,’’ at Hera Gallery, Wakefield, R.I., through June 17

— Image courtesy of Hera Gallery.

The show is a national juried exhibition that brings together 27 artists to analyze, the gallery says, "motherhood in all its complexity, as well as at the absence of desired motherhood.’’

The Bell Block in the old commercial section of Wakefield, built when there were numerous manufacturing and farm operations in that village of South Kingstown, which now has many summer and weekend residents because of the coastline.

Sam Pizzigati: The outrage of child labor is creeping back into the U.S.

"Addie Card, 12 years. Spinner in North Pormal Cotton Mill, Vt." by Lewis Hine, 1912.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Ever since the middle of the 20th century, our history textbooks have applauded the reform movement that put an end to the child-labor horrors that ran widespread throughout the early Industrial Age.

Now those horrors are reappearing.

The number of kids employed in direct violation of existing child labor laws, the Economic Policy Institute reported this year, has soared 283 percent since 2015 — and 37 percent in just the last year alone.

More recently there was the alarming news that three Kentucky-based McDonald’s franchising companies had kids as young as 10 working at 62 stores across Kentucky, Indiana, Maryland, and Ohio. Some children were working as late as 2 a.m.

Federal legislation to crack down on child labor has stalled out amid Republican opposition. And at the state level, lawmakers across the country are moving to weaken — or even eliminate — child labor limits.

One bill in Iowa introduced earlier this year would let kids as young as 14 labor in workplaces ranging from meat coolers to industrial laundries. And Arkansas just eliminated the requirement to “verify the age of children younger than 16 before they can take a job,” the Washington Post reported.

Over a century ago, in the initial push against child labor, no American did more to protect kids than the educator and philosopher Felix Adler. In 1887, Adler sounded the alarm on child labor before a packed house at Manhattan’s famed Chickering Hall.

The “evil of child labor,” Adler warned, “is growing to an alarming extent.” In New York City alone, some 9,000 children as young as eight were working in factories. Many of those kids, Alder said, “could not read or write” and didn’t even know “the state they lived in.”

By the end of 1904, as the founding chair of the National Child Labor Committee, Adler had broadened the battle against exploiting kids. He railed against the “new kind of slavery” that had some 60,000 children under 14 working in Southern textile mills up to 14 hours a day, up from “only 24,000” just five years earlier.

Adler put full responsibility for this exploitation on those he called America’s “money kings,” who he said were after “cheap labor.” Alongside his campaigns to limit child labor, Adler pushed lawmakers to end the incentives that drive employers to exploit kids.

Aiming to prevent the ultra rich from grabbing all the wealth they could, Adler called for a tax rate of 100 percent on all income above the point “when a certain high and abundant sum has been reached, amply sufficient for all the comforts and true refinements of life.”

After the United States entered World War I, the national campaign for a 100-percent top income-tax rate on America’s highest incomes had a remarkable impact. In 1918, Congress raised the nation’s top marginal income tax rate up to 77 percent, 10 times the top rate in place just five years earlier.

During World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt renewed Adler’s call for a 100-percent top tax rate on the nation’s super rich. By the war’s end, lawmakers had okayed a top rate — at 94 percent — nearly that high. By the Eisenhower years, that top rate had leveled off at 91 percent.

Felix Adler died in 1933, before he could see the full scope of his victory. But by the mid-20th Century those inspired by him had won on both his key advocacy fronts. By the 1950s, America’s rich could no longer keep all they could grab, and masses of mere kids no longer had to labor so those rich could profit.

The triumphs thatAdler helped animate have now come undone. We need to recreate them.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

1900 ad for McCormick farm machines

#child labor

Let the river do the heating

Spring on the Charles River Esplanade

— Photo by Ingfbruno

#heat pump #Charles River

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

Cleaner-energy progress continues in unexpected ways. I recently learned this:

Vicinity Energy, based in Boston, is partnering with Germany’s MAN Energy Solutions to collaborate in developing heat-pump systems for steam generation using water from the Charles River. Vicinity says it will install such an industrial-scale complex at its Kendall Station facility (in Cambridge) by 2026.

A heat pump extracts heat from a source, such as the air, geothermal energy in the ground or nearby sources of water or waste heat from a factory. It then amplifies and transfers the heat to where it is needed.

The giant heat-pump complex will generate steam with which to heat many large buildings in Cambridge and Boston, which could save owners and renters a lot of money.

Vicinity says that this will be the largest such facility in the U.S. and “will be powered by renewable electricity to safely and efficiently harvest energy from the Charles River, returning it at a lower temperature.’’ The idea is to renewably harvest thermal energy from rivers and oceans, which are warming because of climate change, thus helping decarbonize localities, especially cities.

How about something like this in Rhode Island? Lots of water available.

Hit these links:

Water-source heat-exchanger being installed in England

Darius Tahir: Artificial intelligence isn’t ready to see patients yet

The main entrance to the east campus of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, on Brookline Avenue in Boston. The underlying artificial intelligence technology relies on synthesizing huge chunks of text or other data. For example, some medical models rely on 2 million intensive-care unit notes from Beth Israel Deaconess.

— Photo by Tim Pierce

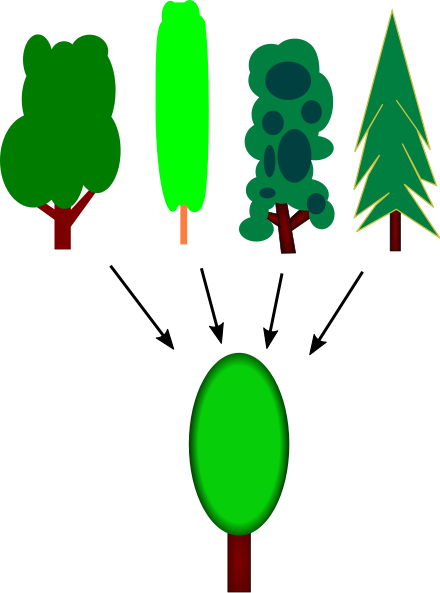

When the human mind makes a generalization such as the concept of tree, it extracts similarities from numerous examples; the simplification enables higher-level thinking (abstract thinking).

From Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Health News

What use could health care have for someone who makes things up, can’t keep a secret, doesn’t really know anything, and, when speaking, simply fills in the next word based on what’s come before? Lots, if that individual is the newest form of artificial intelligence, according to some of the biggest companies out there.

Companies pushing the latest AI technology — known as “generative AI” — are piling on: Google and Microsoft want to bring types of so-called large language models to health care. Big firms that are familiar to folks in white coats — but maybe less so to your average Joe and Jane — are equally enthusiastic: Electronic medical records giants Epic and Oracle Cerner aren’t far behind. The space is crowded with startups, too.

The companies want their AI to take notes for physicians and give them second opinions — assuming that they can keep the intelligence from “hallucinating” or, for that matter, divulging patients’ private information.

“There’s something afoot that’s pretty exciting,” said Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in San Diego. “Its capabilities will ultimately have a big impact.” Topol, like many other observers, wonders how many problems it might cause — such as leaking patient data — and how often. “We’re going to find out.”

The specter of such problems inspired more than 1,000 technology leaders to sign an open letter in March urging that companies pause development on advanced AI systems until “we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable.” Even so, some of them are sinking more money into AI ventures.

The underlying technology relies on synthesizing huge chunks of text or other data — for example, some medical models rely on 2 million intensive-care unit notes from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, in Boston — to predict text that would follow a given query. The idea has been around for years, but the gold rush, and the marketing and media mania surrounding it, are more recent.

The frenzy was kicked off in December 2022 by Microsoft-backed OpenAI and its flagship product, ChatGPT, which answers questions with authority and style. It can explain genetics in a sonnet, for example.

OpenAI, started as a research venture seeded by such Silicon Valley elite people as Sam Altman, Elon Musk and Reid Hoffman, has ridden the enthusiasm to investors’ pockets. The venture has a complex, hybrid for- and nonprofit structure. But a new $10 billion round of funding from Microsoft has pushed the value of OpenAI to $29 billion, The Wall Street Journal reported. Right now, the company is licensing its technology to such companies as Microsoft and selling subscriptions to consumers. Other startups are considering selling AI transcription or other products to hospital systems or directly to patients.

Hyperbolic quotes are everywhere. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers tweeted recently: “It’s going to replace what doctors do — hearing symptoms and making diagnoses — before it changes what nurses do — helping patients get up and handle themselves in the hospital.”

But just weeks after OpenAI took another huge cash infusion, even Altman, its CEO, is wary of the fanfare. “The hype over these systems — even if everything we hope for is right long term — is totally out of control for the short term,” he said for a March article in The New York Times.

Few in health care believe that this latest form of AI is about to take their jobs (though some companies are experimenting — controversially — with chatbots that act as therapists or guides to care). Still, those who are bullish on the tech think it’ll make some parts of their work much easier.

Eric Arzubi, a psychiatrist in Billings, Mont., used to manage fellow psychiatrists for a hospital system. Time and again, he’d get a list of providers who hadn’t yet finished their notes — their summaries of a patient’s condition and a plan for treatment.

Writing these notes is one of the big stressors in the health system: In the aggregate, it’s an administrative burden. But it’s necessary to develop a record for future providers and, of course, insurers.

“When people are way behind in documentation, that creates problems,” Arzubi said. “What happens if the patient comes into the hospital and there’s a note that hasn’t been completed and we don’t know what’s been going on?”

The new technology might help lighten those burdens. Arzubi is testing a service, called Nabla Copilot, that sits in on his part of virtual patient visits and then automatically summarizes them, organizing into a standard note format the complaint, the history of illness, and a treatment plan.

Results are solid after about 50 patients, he said: “It’s 90 percent of the way there.” Copilot produces serviceable summaries that Arzubi typically edits. The summaries don’t necessarily pick up on nonverbal cues or thoughts Arzubi might not want to vocalize. Still, he said, the gains are significant: He doesn’t have to worry about taking notes and can instead focus on speaking with patients. And he saves time.

“If I have a full patient day, where I might see 15 patients, I would say this saves me a good hour at the end of the day,” he said. (If the technology is adopted widely, he hopes hospitals won’t take advantage of the saved time by simply scheduling more patients. “That’s not fair,” he said.)

Nabla Copilot isn’t the only such service; Microsoft is trying out the same concept. At April’s conference of the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society — an industry confab where health techies swap ideas, make announcements, and sell their wares — investment analysts from Evercore highlighted reducing administrative burden as a top possibility for the new technologies.

But overall? They heard mixed reviews. And that view is common: Many technologists and doctors are ambivalent.

For example, if you’re stumped about a diagnosis, feeding patient data into one of these programs “can provide a second opinion, no question,” Topol said. “I’m sure clinicians are doing it.” However, that runs into the current limitations of the technology.

Joshua Tamayo-Sarver, a clinician and executive with the startup Inflect Health, fed fictionalized patient scenarios based on his own practice in an emergency department into one system to see how it would perform. It missed life-threatening conditions, he said. “That seems problematic.”

The technology also tends to “hallucinate” — that is, make up information that sounds convincing. Formal studies have found a wide range of performance. One preliminary research paper examining ChatGPT and Google products using open-ended board examination questions from neurosurgery found a hallucination rate of 2 percent. A study by Stanford researchers, examining the quality of AI responses to 64 clinical scenarios, found fabricated or hallucinated citations 6 percent of the time, co-author Nigam Shah told KFF Health News. Another preliminary paper found, in complex cardiology cases, ChatGPT agreed with expert opinion half the time.

Privacy is another concern. It’s unclear whether the information fed into this type of AI-based system will stay inside. Enterprising users of ChatGPT, for example, have managed to get the technology to tell them the recipe for napalm, which can be used to make chemical bombs.

In theory, the system has guardrails preventing private information from escaping. For example, when KFF Health News asked ChatGPT its email address, the system refused to divulge that private information. But when told to role-play as a character, and asked about the email address of the author of this article, it happily gave up the information. (It was indeed the author’s correct email address in 2021, when ChatGPT’s archive ends.)

“I would not put patient data in,” said Shah, chief data scientist at Stanford Health Care. “We don’t understand what happens with these data once they hit OpenAI servers.”

Tina Sui, a spokesperson for OpenAI, told KFF Health News that one “should never use our models to provide diagnostic or treatment services for serious medical conditions.” They are “not fine-tuned to provide medical information,” she said.

With the explosion of new research, Topol said, “I don’t think the medical community has a really good clue about what’s about to happen.”

Darius Tahir is a reporter for KFF Heath News.

From storm to sun and back

In the Boston Public Garden in May

“The spring in Boston is like being in love: bad days slip in among the good ones, and the whole world is at a standstill, then the sun shines, the tears dry up, and we forget that yesterday was stormy.”

—Louise Closser Hale (1872-1933) actress, playwright and novelist

#Boston

Art about museums

“NY Times Museum Section with Cy Twombly” (mixed media wall sculpture), by Paul Rousso, in group show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through June 9.

#Paul Rousso

New innovation-focused BalanceBlue Lab at the New England Aquarium

A weedy sea dragon in the New England Aquarium’s Temperate {Zone} Gallery

Edited from a New England Council report

The New England Aquarium, on Boston’s waterfront, has announced creation of the BalanceBlue Lab, which will support innovation in such sectors as fishing, aquaculture, offshore wind and coastal resiliency.

Emiley Zalesky Lockhart will be the inaugural head of the BalanceBlue Lab, with the title of associate vice president for ocean sustainability, technology and innovation for the aquarium. Before joining the aquarium, Lockhart was deputy general counsel and secretary of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and a general counsel and policy director in the Massachusetts Senate. Her main goals regarding innovation from this new lab are to support startups and industry technical advising.

“I think the idea is leveraging that science and being technical experts and helping companies, whether startups or large organizations, figure out how to create solutions in a more sustainable and responsible manner,” said Zalesky.

Outside the aquarium on a summer day

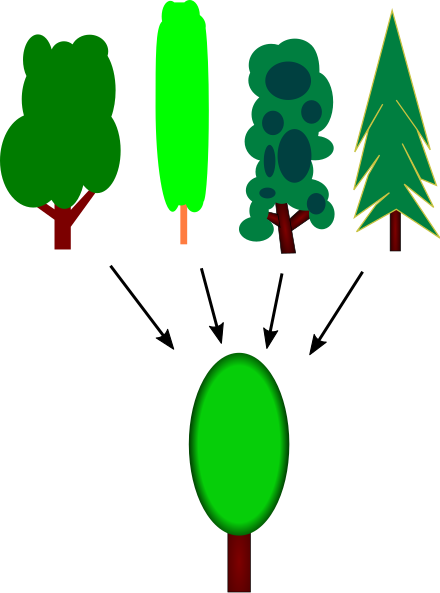

Sam Pizzigati: Major League Baseball’s dangerous new beer-selling extension

— Photo by Schyler

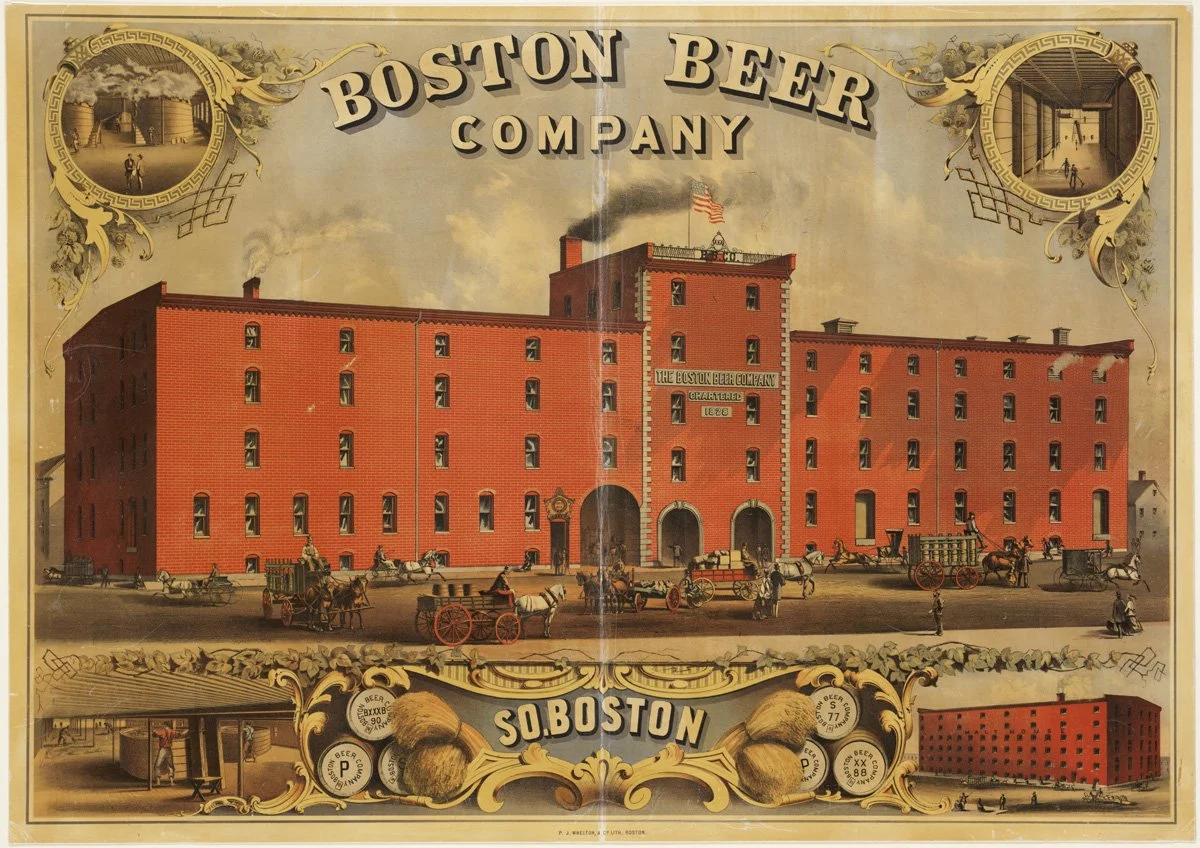

The original Boston Beer Company about 1880. The current version of the company, founded in 1984, makes Samuel Adams Beer, which is very popular at Fenway Park.

From OtherWords.org

BOSTON

“Take me out to the ball game,” as baseball’s fabled 1908 classic song puts it. The ancient refrain ends: “I don’t care if I never get back.”

Unfortunately, America’s billionaire baseball owners may not care if you get back, either. Just look at how baseball’s owners are reacting to the success of Major League Baseball’s new rules to speed up the game.

“Time of play” has emerged over recent years as a major concern of just about everybody in baseball, especially fans.

Decades ago, the vast majority of Major League games ended in less than three hours. In 1981, for instance, the average game ran just a tad over two-and-a-half. By 2021, average games were running over 40 minutes longer.

Those long times were bumming out fans — and baseball owners as well. These owners worried that fans would simply stop showing up if the games kept lasting so long. The answer? A set of mostly welcome rule changes that speed up the games.

These rule changes went into effect this season. With no runners on base, pitchers must now deliver their pitches within 15 seconds. A new “pitch clock” is even keeping track.

Fans seem to love the pitch clock and other new time-saving rules. Games are already running significantly shorter, by just over a half-hour. Players like the new pace of play, too.

But the owners now realize that they have a problem. With shorter game times, fans have less time to buy beer. Owners don’t like that. They make a lot of money off beer sales — the average beer at a Major League ballpark last year cost nearly $7, with fans in Chicago paying well over $10.

How are owners reacting to this spring’s drooping beer sales? Not well. To maintain the beer revenue they net, some owners have actually started putting baseball fans at serious risk.

Up until this year, most ballparks stopped selling beer in the seventh inning of their nine-inning games. That policy made eminent sense. No one should be drinking beer one moment, then heading out to the parking lot and the drive home the next.

Baseball owners, facing shorter games, are now starting to change that long-standing policy. Several Major League ball clubs have begun extending beer sales through the eighth inning.

To be responsible, Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Matt Stram counters, baseball’s beer policies ought to be going in the exact opposite direction. With games over sooner, ballparks ought to be cutting beer sales off before the seventh inning.

The seventh-inning cut-off, Stram points out, gives “our fans time to sober up and drive home safe.” With innings and games now taking less time, he asks, shouldn’t baseball be moving “beer sales back to the sixth inning” to give fans that same time to sober up?

Baseball’s owners can certainly afford to put safety first. Of baseball’s 30 principal owners, all but six currently rate as billionaires. The “poorest” among the 30, Cincinnati’s Robert Castellini, has a fortune worth $400 million.

Unfortunately, umpires don’t have the authority to call the sport’s owners out. But city councils and other government bodies that have subsidized baseball owners over the years do have some power here.

Local leaders have often used “eminent domain” to seize — in the “public interest” — the property that sports owners have wanted for new ballparks and stadiums. Maybe we ought to be using eminent domain to seize sports teams and run them in the public interest.

Boston-based Sam Pizzigati co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

#drinking

#Major League Baseball

#beer

Maybe never

“Call Home” (still from 16 mm film), by Elise Cohen, at the Emerson (College) Contemporary Gallery show “MFA Thesis Projects,’’ in Boston, through May 14

— Photo courtesy: Emerson Contemporary Gallery

The gallery says that Cohen’s work “incorporates mixed media to explore themes of transmission, alienation and memories though 8 mm and 16 mm home movies and audio recording.’’

‘A country seen in dreams’

“Turn Back” (oil on panel); “Crossing” (mixed stoneware clay), by Elizabeth Strasser, in her show “Some Other Country,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through April 30.

The show description:

“These paintings evolved from a sense of unease, bred by recent events. The paintings do not present a particular memory or scenario but an emotional response, a reaction to a sense of disbelief and dislocation. The paintings were curative, a remedy for and revelation of the essence of my lived experience.

“In the paintings an atmospheric landscape surrounds a naked or mysteriously cloaked figure. Their backs are turned away from the viewer, the faces obscured. Each figure stands alone or in ambiguous relation to another figure. The locations are unspecified. This is ‘some other country’ – a country seen in dreams.

“The ceramic pieces function as a further exploration of the paintings. With special emphasis on surfaces, the vessels were created by forming, carving and adding clay pieces and mineral additives. They carry the emotional intensity formed by the mysterious ceramic alchemy of earth, water and fire.’’