Coast in its essentials

“Mother’s Islands” (print) by Swampscott, Mass.-based artist Lydia N. Breed (1925-2019) in the show “Lydia N. Breed: Art of a Community Legacy,’’ at the Lynn (Mass.) Museum, through Sept. 23.

Downtown Lynn. The city once called itself the Shoe (making) Capital of the world.

— Photo by Terageorge

In Swampscott, White Court, now torn down, where President Calvin Coolidge and his wife spent much of the summer of 1925 as the guests of the rich Ohio family who summered there.

Random is better

Richard Rummell's 1906 watercolor view of Harvard’s main campus, in Cambridge

The first telephone directory, printed in New Haven, Conn., in November 1878

“I’d rather entrust the government of the United States to the first 400 people listed in the Boston telephone directory than to the faculty of Harvard University.”

William F. Buckley Jr. (1925 -2008), conservative writer and editor

Llewellyn King: We're lonely in our boxes

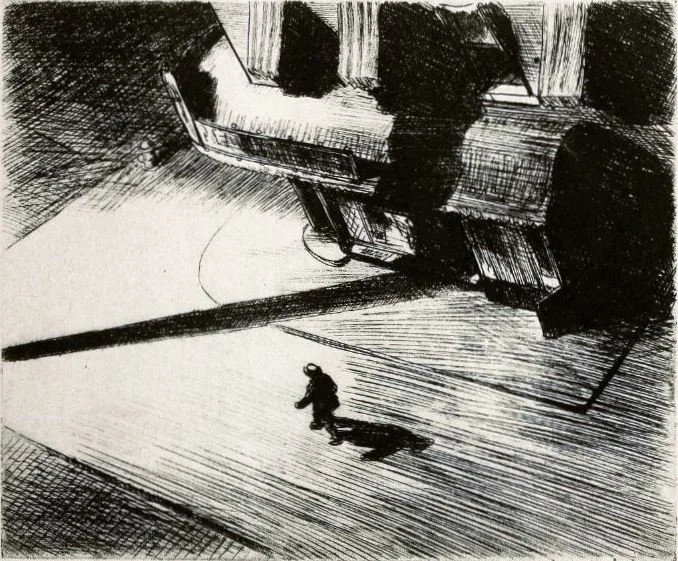

“Night Shadows’’ (1922 etching), by Edward Hopper, created for the magazine Shadowland.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The nation, I read, is in the grip of a loneliness epidemic.

This has all been made worse, one suspects, by the effects of the pandemic-induced lifestyle changes — consequences of the forced isolation that changed social and work practices in ways that haven’t changed back.

Other changes have been coming slowly over the decades, but all add to the lonely life. The way of life has had a trajectory for those who live alone, which has increased the possibility of loneliness.

We isolate ourselves in ways that are new or only decades old. We drive alone. We live in a house or apartment, if single, alone. We work alone in that dwelling, facing a computer or watching a movie on television alone.

I call this the box culture: We drive in a box, live in a box, and, as likely as not, stare into a box as we work.

Changing work patterns are probably a critical part of the structural loneliness that is now rampant. Even if one doesn’t work at home, we work differently. We used to make contacts, and often new friends, by doing business on the telephone. Now we shoot off an email and maybe, if it can’t be avoided, make an appointment to make a video call with several people.

We have wrung out all spontaneity. Making friends is a kind of spontaneous combustion. You might as well be doing business with AI for all the lack of warmth or humor in today’s work interactions.

Then there are work friends. For most of us, it was at work or through work that we made our friends — that is, if they weren’t carryovers from school or college.

People who work together and play together fall in love, sometimes get married, and sometimes meet a friend who undoes a marriage. There is a lot of sex at places of work, although companies might deny it. Note the number of CEOs who marry their assistants.

Another feature of the loneliness structure is that pub life is in decline. The local tavern, even for non-drinkers, was part of the way we lived, and drinking isn’t as pervasive as it once was.

Time was when after work or wishing to see a friend, you went for drinks. People gave drinks parties at noon on weekends: no food, just a convivial glass. That isn’t extinct, but it isn’t what it used to be.

Drinking oils society’s wheels but of course too much, and the wheels come off. Go sit at the bar, and someone will talk to you. There is camaraderie in a saloon.

Entertaining has become more formal. Blame all those cooking shows on television. People don’t have friends over for a hamburger anymore. No. They have to have Steak Diane and a soufflé — a meal with the stamp of Julia Child on it. Result: less dropping in on friends, more isolation.

Of course, there are those who are lonely because of bereavement, sickness, old age and family abandonment. But those things have always been with us. They really suffer loneliness, feel the terrible blanket of isolation.

For those who have decided it is too strenuous to go to the office, that the phone is for messaging, that home loneliness is inevitable because we can’t cook or are ashamed of our homes, join something: a church, a theater group, a book club or do volunteer work.

Much of loneliness, from what I can divine, is a product of how we live now. We sit in our boxes inadvertently avoiding others. Television isn’t friendship, drinking alone isn’t companionship. Go shopping in a store, go to church, go to the pub, work in the food bank, join a book club. As the old AT&T advertisement used to say, “Reach out and touch someone.”

No one can predict how or where great friends or great loves will be found, but certainly not staring at a computer.

Several of my greatest friendships are a result of people who have taken violent exception to something I have written and wanted to meet up to berate me. The facts were wrong. I was evil, I met them to take my medicine, as it were, and parted knowing a new friend.

Surgeon Gen. Vivek Murthy has raised the issue of loneliness. He would be advised to tell people to look at lifestyle. Does it have loneliness baked in?

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Julie Appleby: Fat America (excluding N.E.) —many Americans want those pricey anti-obesity drugs

William Howard Taft (1857-1930) U.S. president in 1909-13 and chief justice in 1921-1903. He was well known for his obesity as well as for his high intelligence and integrity.

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“Unfortunately, a lot of insurers have not caught up to the idea of recognizing obesity as a disease”.

— Fatima Cody Stanford, M.D., an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston

In data comparing obesity rates by state, four of the six lowest obesity states were Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, and Rhode Island. The District of Columbia, Hawaii and Colorado, in that order, were the lowest. New Hampshire and Maine had the 15th and 18th lowest obesity rates, making New England the least overweight part of the U.S.

Many Americans really want to lose weight — and a new poll shows nearly half of adults would be interested in taking a prescription drug to help them do so.

At the same time, enthusiasm dims sharply if the treatment comes as an injection, if it is not covered by insurance, or if the weight is likely to return after discontinuing treatment, a new nationwide KFF poll found.

Those findings display the enthusiasm for a new generation of pricey weight-loss drugs hitting the market and illustrate possible stumbling blocks, as users potentially must deal with weekly self-injections, lack of insurance coverage, and the need to continue the medications indefinitely.

For example, interest dropped to 14 percent when respondents were asked if they would still consider taking prescription medications if they knew they might regain weight after stopping the drugs.

One way to interpret that finding is “people want to lose a few pounds but don’t want to be on a drug for the rest of their life,” said Ashley Kirzinger, KFF’s director of survey methodology. The monthly poll reached out to 1,327 U.S. adults.

The U.S. represents a large market for drugmakers who want to sell weight- loss prescriptions: An estimated 42 percent of the population is classified as obese, according to a controversial metric known as BMI, or body mass index. In the KFF poll, 61 percent said they were currently trying to lose weight, although only 4 percent were taking a prescription medication to do so.

That gap between the 4 percent taking any kind of prescription weight-loss treatment and the number of Americans deemed overweight or obese is the sweet spot that drugmakers are targeting for the new drugs, which include several diabetes treatments repurposed as weight-loss drugs.

The drugs have attracted much attention, both in mainstream publications and broadcasts and on social media, where they are often touted by celebrities and other influencers. Demand jumped and supplies have become limited. About 7 in 10 adults had heard at least “a little” about the new drugs, according to the survey.

The newer treatments include Wegovy, a slightly higher dose of Novo Nordisk’s diabetes drug Ozempic, and Mounjaro, an Eli Lilly diabetes treatment for which the company is currently seeking FDA approval as a weight loss drug.

Weight loss with these injectable drugs surpasses those of earlier generations of weight loss medications. But they are also costlier than previous drugs. The monthly costs of the drugs set by the drugmakers can range from $900 to more than $1,300.

At, say, a wholesale price tag of $1,350, the tab per person could top $323,000 over 20 years.

The drugs appear to work by mimicking a hormone that helps decrease appetite.

Still, like all drugs, they come with side effects, which can include nausea, diarrhea, vomiting and constipation. More serious side effects include the risk of a type of thyroid cancer, inflammation of the pancreas, or low blood sugar. Health officials in Europe are investigating reports that the drugs may result in other side effects like suicidal thoughts.

The KFF survey found that 80 percent of adults thought that insurers should cover the new weight-loss drugs for those diagnosed as overweight or obese. Just over half wanted it covered for anyone who wanted to take it. Half would still support insurance coverage even if doing so could increase everyone’s monthly premiums. Still, 16 percent of those surveyed said they would be interested in a weight loss prescription even if their insurance did not cover it.

In practice, coverage for the new treatments varies, and private insurers often peg coverage to patients’ body mass index, a ratio of height to weight. Medicare specifically bars coverage for drugs for “anorexia, weight loss, or weight gain,” although it pays for bariatric surgery.

“Unfortunately, a lot of insurers have not caught up to the idea of recognizing obesity as a disease,” said Fatima Cody Stanford, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Employers and insurers must consider the potential costs of covering the drugs for enrollees — perhaps for them to use indefinitely — against the potential savings associated with losing weight, such as a lower chance of diabetes or joint problems.

Stanford said the drugs are not a miracle cure and do not work for everyone. But for those who benefit, “it can be significantly life-altering in a positive way,” she said.

It’s not surprising, she added, that the drugs may need to be taken long term, as “the idea that there is a quick fix” doesn’t reflect the complexity of obesity as a disease.

While the drugs currently on the market are injectables, some drugmakers are developing oral weight loss drugs, although it is unclear whether the prices will be the same or less than the injectable products.

Still, many experts predict that a lot of money will be spent on weight-loss products in the coming years. In a recent report, Morgan Stanley analysts called obesity “the new hypertension” and predicted that industry revenue from U.S. sales of obesity drugs could rise from a current $1.6 billion annually to $31.5 billion by 2030.

Julie Appleby is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter

Magical materials

“Dreams of Spring,’’ by Pat McSweeney, in the show “Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Aug. 27. The artist is based in the Charlestown section of Boston.

The gallery says the show features the work of fiber artists who "create new visions" by "reinventing old techniques." The artists use "fabric, thread, wool, reeds, paper, wire and even plastic to create magic.’’

Strange infrastructure

See John Harney’s multi-photo travelogue displaying strange infrastructure, much of it in New England, including the above.

Don’t push back

“Chair 13” (Marino wool and poplar plywood), by Liam Lee, in his show “Spontaneous Generation: The Work of Liam Lee,’’ at the Ogunquit (Maine) Museum of American Art, through Nov. 12

— Photo credit: Ogunquit Museum of American Art

The museum explains that exhibition “showcases the fiber art of Liam Lee. Lee uses hand-dyed and needle-felted wool to explore, as he writes, the ‘breakdown in differences between interior and exterior, the man-made and the natural world.”’

The Ogunquit River (in high summer) exits the Rachel Carson Preserve on the left and flows into the colder waters of the Gulf of Maine.

If you can find them (with video)

Dish of steamers in Gloucester, Mass.

Photo by Paul Keleher

“Today, no summer is really perfect for the New Englander until, napkin under chin, he has eaten his fill of fresh steamed clams, dipped in broth and then in melted butter.’’

From Secrets of New England cooking (1947), by Ella Shannon Bowles and Dorothy S. Towle

That was then. Now it’s hard to find “steamers” (soft-shell clams) because invasive green crabs devour young clams.

Chris Powell: Financial-literacy course a pretense of education

MANCHESTER, Conn.

With Gov. Ned Lamont's recent signature on legislation, Connecticut will be doing more pretending about education. The new law will require high schools to offer and students to take a course on personal financial management. The course will be a prerequisite for graduation.

Of course, young people should have some familiarity with personal financial management as they go out into the world on their own, and many of them, having negligent parents, don't get it at home. Because of parental neglect, students in Connecticut increasingly are chronically absent, missing 10 percent or more of their school days.

But then young people graduating from high school also should master a lot more than personal financial management, starting with basic math and English, even as test scores show that half or more of Connecticut's students graduate from high school without mastering the basics. Actual learning, demonstrated by passing a proficiency test, is not required for students to advance. Students will be required to take the personal financial-management class, but no one will be required to pass it in order to graduate.

Indeed, can students who have not mastered basic math and English master personal financial management? Will making students sit through a course on personal financial management make them competent in math and English and personal financial management, when they are never required to show they have learned anything?

The General Assembly and the governor seem to think so.

Indeed, the legislature, the governor and the state Education Department seem to think that merely prescribing various courses is equivalent to learning. Despite all those courses, Connecticut's only real policy in education is social promotion. While "mastery tests" are occasionally administered in various grades, they mean nothing to students. The tests are just the illusion of academic standards.

Students know this, and many wallow in indifference. Performance on mastery tests might be better if the tests counted for something. In the absence of academic standards, student performance is only a matter of parenting, whose collapse has correlated with student performance.

But restoring standards by conditioning student advancement on academic performance might hurt some feelings and expose parental negligence. So Connecticut's schools figure it's better to award diplomas to everyone and let students discover that ignorance has consequences only once they're on their own, qualified only for menial work and risking lifetime poverty.

Despite the new course in personal financial management, students who graduate without mastering basic math and English may not ever have much personal finance to manage. But the course will let state officials feel better about themselves, as unchallenged students do.

xxx

Why the hysteria about the U.S. Supreme Court's recent decision holding that a Web site creator in Colorado can disregard the state's anti-discrimination law and refuse to create a site for a same-sex wedding?

The office of Connecticut Atty. Gen. William Tong advises that the decision applies to narrow circumstances and will have little impact here and that the state's own anti-discrimination laws remain in force.

But the principle of the Colorado decision will apply in Connecticut, too, and contrary to the hysteria about the case, that principle is just, liberal and in keeping with legal precedent.

That is, when an act of commerce is to a great extent a matter of freedom of expression, anti-discrimination laws cannot compel people to say what they don't want to say. Instead the First Amendment applies. Government cannot compel speech, and creation of a Web site is a form of speech.

This principle can be traced to the Supreme Court's decision in a case from West Virginia is 1943, in which the court held that schools cannot compel students to salute the flag or recite the Pledge of Allegiance.

Anti-discrimination law still applies to the sale of other services and products. The exception covers only matters of expression.

Besides, what same-sex couple would want their wedding's site to be created by someone to whom same-sex marriage is morally objectionable, especially when so many other site creators would welcome the work?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

When it's lush

“Hoosick Valley” (oil on canvas), by John Ford Clymer (1907-1989), in the Bennington Museum show “For the Love of Vermont: The Lyman Orton Collection,’’ in collaboration with the Southern Vermont Arts Center.

— Courtesy of the Vermont Country Store

Beauty from the struggle

"To Slip Away Without a Sound” (dye sub aluminum), by Vaughn Sills, in her show “Joy and Sorrow Intertwined,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Oct. 4-Oct. 29.

The gallery says:

“Vaughn Sills’s compelling photographs create a stage for both the growth and decay, the birth and death, in nature. Her … compositions draw us into a timeless narrative, a metaphor for the struggles of human existence and our failing environment.’’

She is based in Cambridge, Mass., and Prince Edward Island.

Michelle Andrews: Sanders is right to assert that millions can’t find a physician

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) has long been a champion of a government-sponsored “Medicare for All” health program to solve long-standing problems in the United States, where we pay much more for health care than people in other countries but are often sicker and have a shorter average life expectancy.

Still, he realizes his passion project has little chance in today’s political environment. “We are far from a majority in the Senate. We have no Republican support … and I’m not sure that I could get half of the Democrats on that bill,” Sanders said in recent remarks to community health advocates.

He has switched his focus to include, among other things, expanding the primary-care workforce.

Sanders introduced has introduced legislation that would invest $100 billion over five years to expand community health centers and provide training for primary-care doctors, nurses, dentists, and other health professionals.

“Tens of millions of Americans live in communities where they cannot find a doctor while others have to wait months to be seen,” he said when the bill was introduced. He noted that this scenario not only leads to more human suffering and unnecessary deaths “but wastes tens of billions a year” because people who “could not access the primary care they need” often end up in emergency rooms and hospitals.

Is that true? Are there really tens of millions of Americans who can’t find a doctor? We decided to check it out.

Our first stop was the senator’s office to ask for the source of that statement. But no one answered our query.

Primary Care, by the Numbers

So we poked around on our own. For years, academic researchers and policy experts have debated and dissected the issues surrounding the potential scarcity of primary care in the United States. “Primary care desert” and “primary care health professional shortage area” are terms used to evaluate the extent of the problem through data — some of which offers an incomplete impression. Across the board, however, the numbers do suggest that this is an issue for many Americans.

The Association of American Medical Colleges projects a shortage of up to 48,000 primary-care physicians by 2034, depending on variables like retirements and the number of new physicians entering the workforce.

How does that translate to people’s ability to find a doctor? The federal government’s Health Resources and Services Administration publishes widely referenced data that compares the number of primary care physicians in an area to its population. For primary care, if the population-to-provider ratio is generally at least 3,500 to 1, it’s considered a “health-professional shortage area.”

Based on that measure, 100 million people in the United States live in a geographic area, are part of a targeted population, or are served by a health care facility where there is a shortage of primary-care providers. If they all want doctors and cannot find them, that figure would be well within Sanders’ “tens of millions” claim.

The metric is a meaningful way to measure the impact of primary care, experts said. In those areas, “you see life expectancies of up to a year less than in other areas,” said Russ Phillips, a physician who is director of Harvard Medical School’s Center for Primary Care. “The differences are critically important.”

Another way to think about primary-care shortages is to evaluate the extent to which people report having a usual source of care, meaning a clinic or doctor’s office where they would go if they were sick or needed health-care advice. By that measure, 27 percent of adults said they do not have such a location or person to rely on or that they used the emergency room for that purpose in 2020, according to a primary-care score card published by the Milbank Memorial Fund and the Physicians Foundation, which publish research on health care providers and the health care system.

The figure was notably lower in 2010 at nearly 24 percent, said Christopher Koller, president of the Milbank Memorial Fund. “And it’s happening when insurance is increasing, at the time of the Affordable Care Act.”

The U.S. had an adult population of roughly 258 million in 2020. Twenty-seven percent of 258 million reveals that about 70 million adults didn’t have a usual source of care that year, a figure well within Sanders’ estimate.

Does Everyone Want This Relationship?

Still, it doesn’t necessarily follow that all those people want or need a primary-care provider, some experts say.

“Men in their 20s, if they get their weight and blood pressure checked and get screened for sexually transmitted infections and behavioral risk factors, they don’t need to see a regular clinician unless things arise,” said Mark Fendrick, an internal-medicine physician who is director of the University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design.

Not everyone agrees that young men don’t need a usual source of care. But removing men in their 20s from the tally reduces the number by about 23 million people. That leaves 47 million without a usual source of care, still within Sanders’ sbroad “tens of millions” claim.

In his comments, Sanders refers specifically to Americans being unable to find a doctor, but many people see other types of medical professionals for primary care, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

Seventy percent of nurse practitioners focus on primary care, for example, according to the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. To the extent that these types of health professionals absorb some of the demand for primary-care physician services, there will be fewer people who can’t find a primary-care provider, and that may put a dent in Sanders’ figures.

Finally, there’s the question of wait times. Sanders asserts that people must wait months before they can get an appointment. A survey by physician-staffing company Merritt Hawkins found that it took an average of 20.6 days to get an appointment for a physical with a family physician in 2022. But that figure was 30 percent lower than the 29.3-day wait in 2017. Geography can make a big difference, however. In 2022, people waited an average of 44 days in Portland, Ore., compared with eight days in Washington, D.C.

Our Ruling

Sanders’s assertion that there are “tens of millions” of people who live in communities where they can’t find a doctor aligns with the published data we reviewed. The federal government estimates that 100 million people live in areas where there is a shortage of primary care providers. Another study found that some 70 million adults reported they don’t have a usual source of care or use the emergency department when they need medical care.

At the same time, several factors can affect people’s primary-care experience. Some may not want or need to have a primary-care physician; others may be seen by non-physician primary care providers.

Finally, on the question of wait times, the available data does not support Sanders’s claim that people must wait for months to be seen by a primary care provider. There was wide variation depending on where people lived, however.

Overall, Sanders accurately described the difficulty that tens of millions of people likely face in finding a primary-care doctor.

We rate it Mostly True.

Michelle Andrews is a reporter for KFF Health News.

UNH moves into marine autonomous vehicle sector

At the Judd Gregg Marine Research Complex, 15 miles from UNH’s main campus, in Durham, and at the mouth of Portsmouth Harbor in New Castle, N.H. It supports research, education and outreach in marine biology, oceanography and ocean engineering, with particular emphasis on marine biology and ecology, aquaculture, acoustics and ocean mapping, invasive species, autonomous surface vehicle research, ocean acidification, and renewable energy.

A University of South Florida researcher deploys Tavros02, a solar-powered marine autonomous vehicle.

— Photo by Bgregson

Edited from a New England Council report

“The University of New Hampshire has opened of a new maritime autonomy innovation hub.

“In collaboration with the Paris-based nautical-technology firm, Exail, UNH will use the new center as an operating base for marine autonomous vessels. The hub will produce pioneering un-crewed surface vessels, house a center for international remote autonomous operations, and train future generations on the use of remote autonomous vehicles. As a result, this effort will expand access to public and private customers and offer innovative solutions to help support the blue economy.

“‘This exciting collaboration will not only be good for Exail and UNH students and researchers but also good for New Hampshire and the nation,’ said Larry Mayer, director of UNH’s Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping. ‘We anticipate that it is just the start of bringing many of our other industrial partners and government colleagues to the state as we create a local engine for the new blue economy.”’

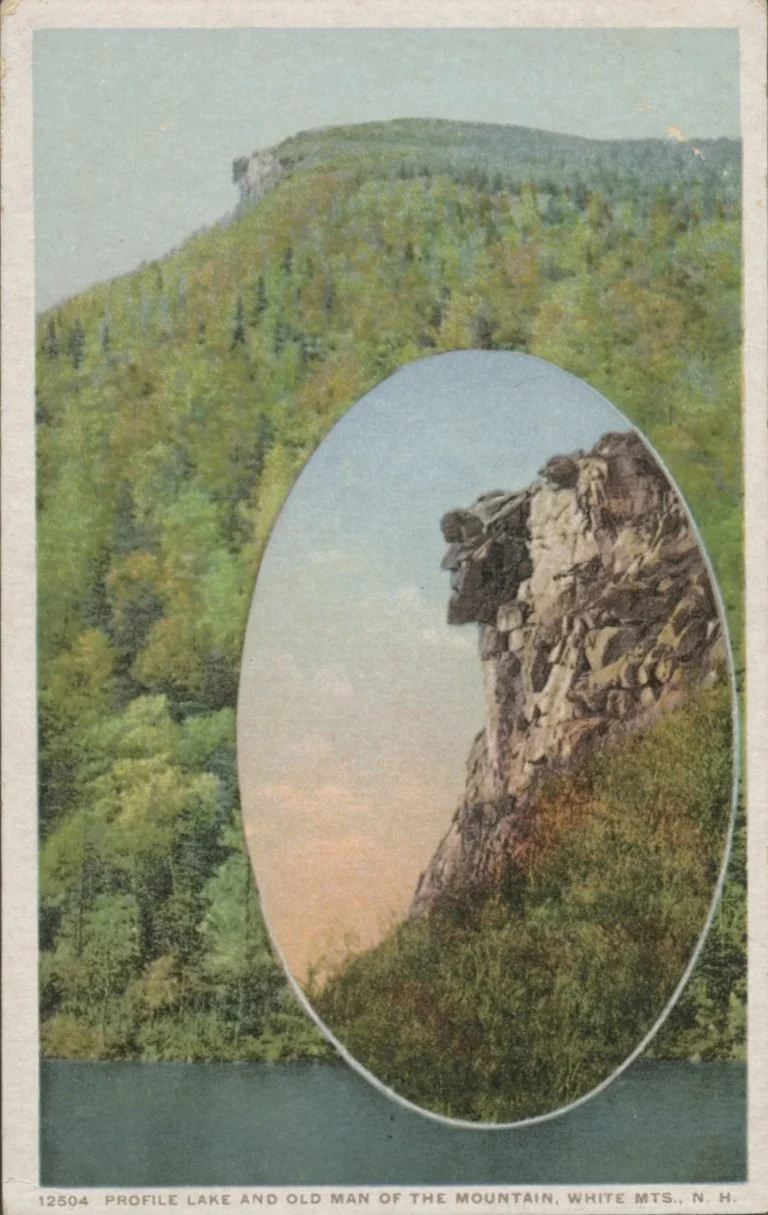

The old man in the Granite State’s heart

From the show “An Enduring Presence: The Old Man of the Mountain,’’ at the Museum of the White Mountains, at Plymouth State University, Plymouth, N.H., through Sept. 16.

The museum says:

“On May 3, 2003, New Hampshire awoke to a world in which an iconic stony face no longer looked out over Franconia Notch. For over two centuries, the Old Man of the Mountain had captured the imagination of storytellers, artists, writers, statesmen, scientists, entrepreneurs, and tourists. Twenty years later the Old Man of the Mountain remains a prominent New Hampshire icon and can still be found as an official and unofficial emblem across the state and beyond. This exhibition explores the history of the Old Man of the Mountain and the ways in which its images and narratives symbolized and reflected the evolving identity of New Hampshire and its citizens. The extraordinary story of the people and technology involved in the innovative efforts to preserve the Old Man’s place atop Cannon Mountain will also be told.’’

Llewellyn King: Despair and danger

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Body language is the new political voice in America.

The language is universal and easily learned because it has just four components: eye-rolling, sighing and shrugging, accompanied by turning hands up.

“Oh my God, it’s a disaster,” is one translation. Another might be, “Don’t ask me, I didn’t sign on for this.”

It belongs — this silent expression of despair about the presidential election, unfolding for 2024 — to old-line Republicans and to a wide swath of Democrats, too.

Political discussion has ended in these groups, replaced by the kind of fatalism summed up in the words of the Irish poet William Butler Yeats that we are slouching toward Bethlehem.

Of course, as Washington Post columnist George Will says, the inevitable isn’t necessarily inevitable. However, at the moment, it looks as if it is.

The despair is spread pretty evenly among Democrat, many of whom consider President Biden too old, and Vice President Kamala Harris not up to the job she has, let alone the presidency.

At 80, Biden is showing reduced vigor and limited mobility, and he favors scripted speeches. This from a politician who was famous for nonstop talking.

Over the years, like other reporters, I have often thought, “Joe, you have made your point, now stop.” These days, you wait in vain for him to go off script. His speeches, which he reads from a Teleprompter, sound as though they were prepared by a committee — lifeless repetition.

He never holds a press conference, a sign of dwindling confidence.

The bigger fear in the Democrats isn’t that Biden is too old but that Harris, at some point, may become president. She has proven herself to be woefully inept and incoherent.

In every assignment Biden has handed her on which she could have shown her worth, she has failed or simply not done. Remember, she was Biden’s point person on the border crisis? She hasn’t been heard from as such.

This past spring, she went to Ghana, Tanzania and Zambia to counter the Chinese and chose to make it an occasion to apologize for slavery. I was born and raised in Africa, in what is now called Zimbabwe, and have traveled extensively on the continent, and slavery isn’t a burning issue. The high point of this visit was Zambia, where Harris’s paternal grandfather came from and where she was welcomed.

China has three great appeals to African countries: It asks no questions, doesn’t lecture on human rights, and pays off the ruling elites, trading these indulgences for minerals.

While Biden and Harris may seem a dangerous pair, Donald Trump, twice indicted (so far), twice impeached, now reduced to feeling sorry for himself on a colossal scale, is terrifying. He has promised an administration of vengeance.

Whereas I can’t find any Democrats who are enthusiastic about the Biden-Harris ticket, I certainly can find far-right Republicans who love Trump. Mostly, they are the working-class White voters, who were once the mainstay of the Democratic Party and now believe that the America they know and want to preserve can only be saved by the reprehensible Trump, with his relentless abuse of all who cross him and endless lachrymose pity for himself.

Trump’s defense of himself is risible, but the faithful Trumpsters believe in him — as much as ever.

They aren’t statistics to me. Recently, my wife and I were eating at a Chinese restaurant in Rhode Island when a couple with a small child took the booth behind us. You might call them the salt of the earth: working people doing their best to raise a family. The husband was complaining loudly about the high cost of living. Then, after seeing Trump on an overhead TV, he said to his wife, “The only honest man is Trump.”

That young father wasn’t alone.

At a neighborhood pub that, in the British sense, is our “local,” the owner and patrons know that both my wife and I are journalists, and because Rhode Island PBS airs our program, White House Chronicle, we are treated with deference. But that doesn’t prevent good, hard-working, fellow patrons, mostly of Italian, Irish and Portuguese stock, from lambasting the media within earshot of us. “It’s all lies.” “They hate Trump because he tells the truth.” They say things like that because they believe them. They are the Trump base.

When I hear that stuff, how do I react? Well, I roll my eyes, sigh, shrug my shoulders, and, if no one is looking, I turn my hands up to the heavens.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Vermont’s sweet shareholders

The Ben & Jerry’s factory, in Waterbury, Vt.

“One out of every 100 families in Vermont was a part owner of Ben and Jerry’s.”

—Jerry Greenfield (Jerry, of Ben and Jerry’s)

Ben & Jerry's Homemade Holdings Inc., commonly known as Ben & Jerry's, makes ice cream, frozen yogurt and sorbet. Founded in 1978 in Burlington, Vt., the company went from a single ice-cream parlor to a multi-national brand. It was sold in 2000 to the multinational conglomerate Unilever but operates as a (somewhat) independent subsidiary. It’s now based South Burlington, Vt., with its factory in Waterbury, Vt.

Saying, hearing, painting and looking

“Muse Becomes Poet,’’ by Boston area-based Donald Langosy, in his show “Art/Poetica,’’ at the Multicultural Arts Center, East Cambridge, Mass., Oct 10-Nov. 24. The gallery says the show explores “the time-honored relationship between poets and visual arts.’’

Some famous poets were also visual artists, such as E.E. Cummings (1894-1962), whose 1920 self-portrait is above. He was born in Cambridge, Mass., and died at his vacation house, in Madison, N.H., in 1962.

Too big to save?

Cranston Street Armory, in Providence

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

What to do with that huge rundown white elephant, the castle-like Cranston Street Armory in Providence? It’s hard to see how it could be rehabbed, whatever the grandeur of its exterior and some of its interior space. (There are other old fort-or-castle like armories in New England.)

The only thing that makes much sense to me is if the entire edifice were transformed into a one-building college campus; there’s even plenty of room for athletics. (And an indoor farm?} The idea, floated by some, of making it into some sort of regional meeting center, say for big events that might otherwise go to the Providence Civic Center, and a home for a wide range of businesses, seems implausible, at least if the state and city are unable or unwilling to fork over many tens of millions of dollars to retrofit the complex. Even with massive retrofitting, how many folks would want to come to that neighborhood to work or for events? Maybe more than I’d think?

Old places like Rhode Island have many big buildings that are no longer used for their original purposes. Nothing lasts, and some of these impressive piles will just have to be torn down.

I had a fantasy dream that someone very, very rich would buy the armory and turn it into his/her private palace, as Dr. Barrett Bready did with the glorious granite former Old Stone Bank Building on Providence’s South Main Street. But as big as that it is, it’s minuscule compared to the Cranston Street Armory.

If only Rhode Island had a king or queen (a constitutional monarch, of course!); the armory could be turned into a royal palace. Maybe surround it with a few cannons.

State Arsenal and Armory in Hartford

— Photo by Prakashkumar014 -

Sonali Kolhatkar: Elite colleges’ legacy admissions are ‘affirmative action’ for the rich

Via OtherWords.org

Who will benefit from the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent ruling striking down race as a factor in college admissions? Mostly, just wealthy white people.

That’s because the ruling refused to touch so-called “legacy admissions.” Colleges are free to continue giving preferential treatment to the children of alumni, donors, and other well-connected, privileged people.

Former President George W. Bush is a classic example of how legacy admissions are effectively a form of affirmative action for the rich. How else would a mediocre student like him be admitted to Yale University? Because his father and grandfather were Yale alumni.

Legacy admissions give wealthy people a leg-up in ensuring that generational wealth, privilege and power remain in the family. And the origins of the practice lie in antisemitism.

According to Jerome Karabel’s book The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, legacy admissions were a way to reduce the number of Jewish Americans who were academically qualified to win admission but who didn’t fit into the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant tradition that such schools uplifted. Elite universities changed the goal posts, ensuring that family ties gave mediocre but well-connected white Protestants an edge.

That preferential treatment continues today, reinforcing white supremacy.

For example, according to the Ivy League admissions consulting firm Admission Sight, “more than 36 percent of the students in the Harvard Class of 2022 are descendants of previous Harvard students.” Students whose parents didn’t attend Harvard had, since 2015, “a five times lower chance of being accepted.”

And where legacy admissions don’t apply, wealthy families have yet another entry point: plain old bribery.

In a court case stemming from the college admissions scandal that broke in 2019, it was revealed that the University of Southern California was willing to consider applicants whose families offered large donations to the school. These “special interest” or “VIP” donors received preferential treatment.

Even the public University of California system has been found to give preferential treatment to wealthy white applicants. A state audit found that at least 64 people, most of them wealthy and white, were admitted in recent years to UC schools solely because of their family connections and donations.

The Supreme Court’s latest ruling on affirmative action doesn’t end race-based preference. For wealthy white people, it further entrenches it.

The good news is that Neil Gorsuch, a Supreme Court conservative who voted to end affirmative action, also agreed with his dissenting liberal colleagues that legacy admissions had to end.

President Biden responded similarly. “I’m directing the Department of Education to analyze what practices help build… more inclusive and diverse student bodies and what practices hold that back,” Biden said after the ruling. That includes “legacy admissions and other systems that expand privilege instead of opportunity.”

As Democratic U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley, of Oregon, told MarketWatch, “The longstanding use of legacy and donor preferences in admissions has unfairly elevated children of donors and alumni — who may be excellent students and well-qualified, but are the last people who need an extra leg up in the complicated and competitive college admissions process.”

To that end, Merkley and Democratic Rep. Jamaal Bowman, of New York, recently introduced the Fair College Admissions for Students Act, which would end preferential treatment for applications from wealthy, privileged families.

Whether or not the bill moves in Congress, the fact remains that college admissions are biased — toward wealthy white Americans. Those conservatives celebrating the end of affirmative action have exposed yet again how their real agenda is to protect the unfair advantages of wealth.

Sonali Kolhatkar is the host of Rising Up With Sonali, a television and radio show on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. This commentary was produced by the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and adapted for syndication by OtherWords.org.

Fantastical ferns

“Fernland” (oil painting), by Concord, N.H.-based artist Pamela R. Tarbell’s in her show “Marsh Kaleidoscope,” at Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum, in Boston’s Jamaica Plain and Roslindale sections, through Oct. 7

Coryphopteris simulata, synonym Thelypteris simulata, is a species of fern native to the Northeastern United States. It is known by two common names: bog-fern and Massachusetts fern.

Sign outside New Hampshire’s State Capitol Building

—Photo by Karmafist

#Pamela R. Tarbell #Arnold Arboretum

‘