Beech tree disease imperils forest ecosystem

American beech tree

— Photo by Jean-Pol GRANDMONT

From ecoRI News (ecori.org) article by Mike Freeman

Beech leaf disease, which has devastated northern hardwood forests since its discovery in Ohio in 2012, has spread throughout Rhode Island’s beech trees.

“It would change the whole forest ecosystem if they go,” said Heather Faubert, director of the University of Rhode Island’s Plant Protection Clinic. “We know what’s infected them but don’t know yet how it spreads, only that it spreads very quickly. It was first identified in Ashaway in 2020 and is now statewide.”

The disease is infecting beech trees in all New England states except Vermont, and was first detected in Connecticut in 2019.

Faubert’s general description tracks the terrible template that has wiped out or is en route to wiping out several native North American tree species. Details differ, but the plot never changes: People notice dying trees, a cause is identified, swaths of forest succumb as more becomes known, then to various effects preventative, palliative, or restorative measures are taken, often in combination. American chestnut exists on life support, American elm is greatly diminished, and currently eastern hemlock, the entire ash genus, and now American beech are all in dire peril.

As Faubert noted, what exactly causes beech leaf disease (BLD) and how it spreads are currently unknown, though the critical vector is Litylenchus crenatae mccannii, a nearly microscopic nematode, or worm, that feeds on beech leaves.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Maine lushness

"Boothbay Harbor Botanical Gardens" (oil on panel), by Louis Guarnaccia, at Bayview Gallery, Brunswick, Maine.

David Warsh: Hamilton, the Fed and the debt-ceiling crisis

Statue of Alexander Hamilton, by William Rimmer, on Commonwealth Avenue, Boston

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

This column, “Economic Principals,’’ was founded as a Boston Globe newspaper column, in 1983, on the premise that most of the important action in economic policy took place in universities – not just departments of economics and history, but in other social- sciences departments as well, and in schools of law, business, and government.

Quacks thrived in the days immediately after Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential victory, though his administration before long began to exhibit great good sense, as if to illustrate my contention. And while nothing I have learned since has changed my mind, the column’s predicate has occasionally caused him to overlook some exceptional journalists along the way.,

One such is John Steele Gordon, author of Hamilton’s Blessing: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Our National Debt (Walker, 1997) A revised edition appeared in 2010. The book is of special interest in current circumstances – the crisis over an attempt to impose a limit on the government’s borrowing capacity in exchange for promises of future cuts in spending on social-welfare programs.

Alexander Hamilton has become a celebrity since then, thanks to Lin-Manuel Miranda and another exceptional journalist, Ron Chernow, on whose biography of Miranda’s smash-hit musical , Hamilton, was based, and for good reason. The Caribbean-born Hamilton was the only Founding Father except Benjamin Franklin not endowed by birth with privilege (“the bastard brat of a Scotch peddler,” John Adams called him). Moreover, having grown up abroad, he possessed no fundamental loyalty to any one of the 13 colonies; he was, instead, a nationalist. Above all, Hamilton was a prodigy.

After serving as George Washington’s aide-de-camp during the War of Independence, he helped lead the battle to dismantle the Articles of Confederation. Once the new Constitution was adopted, Washington named him treasury secretary, and, in short order, Hamilton assembled much of the fiscal and monetary machinery of the new republic. His program had three main struts.

He nationalized the obligations of the states, incurred during the seven years of war. “A national debt” he wrote to a friend, “if it is not excessive, will be to us a national blessing.” He established taxes to reliably pay those debts: at first, tariffs on imported goods; when those revenues were insufficient, sales taxes on consumption goods, including whiskey. Finally, he successfully lobbied to create a Bank of the United States, modeled on the Bank of England, owned by private banks in partnership with the federal government, to issue currency and to assure its reliability; and to oversee the banking industry in general.

In 1804, Hamilton was killed by Aaron Burr in a duel. A dozen years later, the charter First Bank of the United States was allowed to expire. The Second Bank of the United States replaced it, but its charter, too, was allowed to lapse, in 1836, after a battle with President Andrew Jackson.

The National Banking Act of 1863 established the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and preserved the North’s ability to borrow against “the full faith and credit of the United Sates, during the Civil War (as described in Ways and Means: Lincoln and his Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War (Penguin, 2022), by Roger Lowenstein, another exceptional journalist.)

Only after the Panic of 1907, in which the American banking system required rescue by a syndicate organized by J.P. Morgan, was Hamilton’s original proposal smuggled back into law, in the form of the Federal Reserve System. Had the 20th Century version been properly named, as Hamilton intended, the Fed’s partnership with the Treasury Department might be better understood today.

The Treasury borrows money from willing lenders all over the world – that is, it accepts deposits and issues bonds and bills in return, on behalf of the federal government. The Fed is among its customers, buying or selling those government securities as a means of conducting monetary policy by raising and lowering interest rates as need be. Exchanges rates fluctuate based on that monetary policy, making the U.S. dollar the preferred currency of global markets.

By threatening the Treasury Department’s ability to borrow, Congress is tampering with the trustworthiness of the system itself. The root of the domestic argument has to do with the purposes for which the government borrows and spends the money – to defend the nation and make war, to finance its system of social welfare, or simply to keep the bank of the Fed running smoothly. The journalist Gordon writes:

In the 1860s we used the national debt to save the Union. In the 1930s we used it to save the American economy. In the 1940s we used it to save the world. So surely Hamilton was right, and the American national debt has been an immense national, indeed global, blessing. But is it still? Or is it now a crippling curse?

In short, it is the second strut of Hamilton’s program that is contested – the Treasury Department and its system of taxation. Income and expenditures are out of line and the imbalances have been growing for decades. Republicans generally favor cutting benefits – the Social Security and health-care systems. Democrats generally favor raising taxes.

While you are waiting for these issues to be addressed in next year’s elections, Hamilton’s Blessing is a beguiling introduction to the fundamental problem.

xxx

Speaking of which, a recent biography of Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Yellen: The Trailblazing Economist Who Navigated an Era of Upheaval (Harper, 2022), by Jon Hilsenrath, yet another exceptional journalist, has received less attention than it deserves.

Hilsenrath notes that Fed chair Ben Bernanke relied on an inner circle of advisers during the financial crisis of 2007-08, all in Washington or New York. As president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Yellen was not among them.

As treasury secretary, Yellen is at the center of the drama of the debt- ceiling negotiation, perhaps more central to the matter, as his principal adviser, than President Biden himself. The story of the formation of the character of this remarkable woman will make interesting reading long after she has left office.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

‘When the wind stops’

At the Rhode Island Veterans Memorial Cemetery, in Exeter

“The March of Time” (Decoration Day, later renamed Memorial Day) in Boston, by Henry Sandham (1842-1910), Canadian painter who lived in Boston for 20 years.

Life contracts and death is expected,

As in a season of autumn.

The soldier falls.

He does not become a three-days personage,

Imposing his separation,

Calling for pomp.

Death is absolute and without memorial,

As in a season of autumn,

When the wind stops,

When the wind stops and, over the heavens,

The clouds go, nevertheless,

In their direction.

— Wallace Stevens (1879-1955), famed American Modernist poet. He was also an insurance executive and lawyer. He lived and worked in Hartford.

The way they look in memory

“Considering the Course of Events’’ (acrylic, ink and graphite), by Chestnut Hill-based artist Norman Finn, in his show “Faces Along the Way: Real and Imaginary,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, June 20-July 2.

He explains:

“I have tried to convey through the canvas some of the individuals that made lasting impressions as well as triggering my imagination. The paintings represent images from my childhood and my extensive travels throughout the world.

“A group within the collection are done with a technique I call ‘Modular Art,’ which are pieces applied to the canvas that creat.e dimension to the composition. These painting are more in the realm of the imagination with an interesting color palette. Painting this collection enabled me to relive some of the forgotten relationships and fond memories.”

Sunset at Hammond Pond in Chestnut Hill

— Photo by NewtonCourt

Not so much now

Southern Maine beach house in 1914

“The first ‘hot’ day of the season has happened. I put ‘hot’ in quotation marks because in Maine the term is strictly relative. Most people can live in Maine for years without learning what hot really means; some of them may never learn unless they leave the state.’’

— John Cole (1923-2003), Maine journalist, author and environmentalist, in his book In Maine (1974)

‘Much harder work’

Mindy Kaling

“Write your own part. It is the only way I've gotten anywhere. It is much harder work, but sometimes you have to take destiny into your own hands. It forces you to think about what your strengths really are, and once you find them, you can showcase them, and no one can stop you.”

— Mindy Kaling (born 1979), American actress, comedian, screenwriter and producer. She grew up in Cambridge, Mass., and graduated from Dartmouth College.

Blurring separations

“A Mata Te Se Come,’’ (sculpture) , by UYRA, a Brazilian artist, at the Currier Museum of Art , Manchester, N.H.

—Photo by Lisa Hermes

—Image courtesy of Currier Museum of Art

The museum says that the show consists of videos and photos of costumes/sculptures made from natural materials that "blur conventional separations between humans, {other} animals, and plants."

On the Irish Riviera

Hough’s Neck, in Quincy, Mass., once a popular summer place for middle-class Irish-Americans.

From The New England Historical Society

“What better New England place to spend Memorial Day than the Irish Riviera? Beaches in Wollaston {part of Quincy, Mass.}, Nantasket {part of Hull, Mass.} and Hough’s Neck {in Quincy} have been popular vacation spots for Irish immigrants and their offspring since the late 19th Century.

“But {Greater Boston} South Shore beaches weren’t only for swimming. In Scituate, the most Irish town in America, immigrants used to harvest red algae – a practice known as mossing. There is actually a Maritime and Mossing Museum run by the Scituate Historical Society. Open Sunday afternoons, it is set in the 1739 residence of Capt. Benjamin James on the Driftway. Exhibits describe the Portland Gale, Scituate’s many shipwrecks, Thomas W. Lawson’s seven-masted schooner and Irish mossing.’’

To read more, please hit this link.

The Lawson Tower, in Scituate

David Warsh: The WSJ’s editorial page is a big loser in the alleged ‘Russia hoax’

Putin with his most important admirer in 2018. In 2008, Donald Trump Jr. said: "In terms of high-end product influx into the US, Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross-section of a lot of our {Trump Organization’s} assets…. Say, in Dubai, and certainly with our project in SoHo, and anywhere in New York. We see a lot of money pouring in from Russia."

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The last slow-motion replay of the confusion that accompanied the election of Donald Trump in the long-ago autumn of 2016 has finally been released to the public. Special Counsel John Durham’s report joined the 484-page review by Justice Department Inspector Michael Horowitz on the shelf, along with the two-volume report of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, all of them supposedly motivated by the FBI’s Operation Hurricane Crossfire investigation of Trump’s connections with Russia.

I couldn’t let the occasion pass without saying something about where the various questions were first broached: on the front pages of leading American newspapers. The disagreement between Horowitz and Durham boiled down to whether the FBI investigation of the Trump campaign was “adequately predicated” by the information received. Horowitz thought yes; Durham thought no. Future historians, however, will look beyond legalistic wrangling to see the story whole.

I leave aside the Senate Intelligence Committee 2020 report on Russian interference in the 2016 election, because I wrote nothing about it. The bipartisan report confirmed the Intelligence Community Assessment of January 2017, that Russia tried to swing the 2016 election to Trump. Here, the story is mainly a reminder of what went on among newspapers behind the scenes.

First, recall the high points of that turbulent summer. The ongoing ruckus over Hillary Clinton’s emails. WikiLeaks release of some of her campaign’s messages. its contents. FBI Director James Comey’s exoneration of Clinton for having maintained a private email server. Trump’s call of attention to 30,000 missing emails: “Russia, if you’re listening….” The sudden appointment of pro-Russia lobbyist Paul Manafort as Trump campaign chairman. The long history of Trump’s own business dealings with wealthy Russians. Comey’s last-minute announcement of the discovery of Anthony Weiner’s misplaced laptop computer, that contained some unexamined Clinton emails.

Then came the events after November. The 22-day tenure of Michael Flynn as national security adviser. Emergent accounts of “the Steele Dossier.” The January briefings of Presidents Obama and Trump by four national security chiefs, describing questions that had been raised. Trump’s firing of Comey. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s Oval Office visit the next day. The strong-man handshake with Putin in Helsinki.

Now to the back story. Star reporter Devlin Barrett quit The Wall Street Journal to become The Washington Post’s top man on the FBI beat. Deputy WSJ editorial page editor Bret Stephens quit for a column at The New York Times, and began a weekly conversation with fellow columnist Gail Collins in which the neo-conservative and the liberal traded barbs and compliments in a conspicuously civil manner. WSJ editor-in-chief Gerard Baker was quietly removed from the news side of the paper, by its Murdoch family owners, and given a column on the op-ed page instead.

In 2008, Peter Baker became the chief White House correspondent at the NYT, after many years covering presidents for The Washington Post; he and his wife, The New Yorker’s Susan Glasser, published The Divider: Trump in the White House, 2017-2021, in 2022. Dan Balz remained the WPost’s principal national political commentator. And star reporter Maggie Haberman emerged as the exemplar-in-chief of a style of independent reporting extolled the other week by NYT publisher Arthur Gregg Sulzberger, in an essay in the Columbia Journalism Review.

The loser in all this has been the editorial pages of The Wall Street Journal, which have been all in for Trump, from before the beginning of his presidency until nearly the end. It’s up to others to prove this. I depend on a trio of columnists to follow the story where they think it has gone: Holman Jenkins Jr.; Daniel Henninger; and Kimberly Strassel. Jenkins is the one whom I read regularly; all three have been enthusiastic promoters of Durham’s preposterously narrow police procedural rendition of events.

The WSJ Editorial Board has focused on the long-since discredited Steele dossier to make their case: “Now the Durham report makes clear that the Mueller team failed to investigate how the collusion probe began as a dirty trick by the Clinton campaign and how the FBI went along for the ride.” There’s no free link for this piece; four years exploring a rabbit hole produces a bad case of tunnel vision, nothing more. See a column by Peggy Noonan (subscription required), in the same paper, for a much more sensible view.

The other day columnist Gerry Baker did produce an interesting surprise (subscription required): a what-if endorsement of Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s possibilities as a 2024 presidential contender. “If Trump and DeSantis both stumble, don’t rule out a late entry by the Virginia governor.” The 25-year Carlyle Group veteran upset former Democratic governor Terry McAuliffe in 2021, apparently finding a path past Trump. Wrote Baker:

[T]he Virginia governor has established himself as the foremost exponent of what we might term a new Republican fusionism: happy culture warrior, taking on the establishment orthodoxies on critical race theory, transgender rights and the rest of the extremist woke tyranny. But he’s also scored governing successes on the economy, delivering a solid tax cut and focusing efforts on lifting living standards for the poorest Virginians.

WSJ Editorial Page Editor Paul Gigot is approaching retirement, twenty years after replacing the legendary Robert Bartley. I once believed that the Murdochs couldn’t do better than to hire back Bret Stephens, who, until he left for the NYT had been a leading contender for the job. That seems less likely now.

Meanwhile, never mind Fox News and its recently dismissed faux-populist commentator Tucker Carlson. The WSJ’s editorial pages are far more important as a nursery of ideas about America’s conservative tradition. What the Murdoch family needs now is a nimble “Republican fusionist” in the editor’s chair – to nurture whatever that tradition is next to become.

The new editor’s first task will be to put an end to the Editorial Board’s repetitive support of the first of Trump’s two great lies: that there was no legitimate reason for the Justice Department or the Senate’s Intelligence Committee to probe the newly inaugurated president’s Russia connections.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

Mommy dearest?

“Urban Toile” (relief cut), by Boston artist Ellen Shattuck Pierce, in the group show “Oh, Mother,’’ at Hera Gallery, Wakefield, R.I., through June 17

— Image courtesy of Hera Gallery.

The show is a national juried exhibition that brings together 27 artists to analyze, the gallery says, "motherhood in all its complexity, as well as at the absence of desired motherhood.’’

The Bell Block in the old commercial section of Wakefield, built when there were numerous manufacturing and farm operations in that village of South Kingstown, which now has many summer and weekend residents because of the coastline.

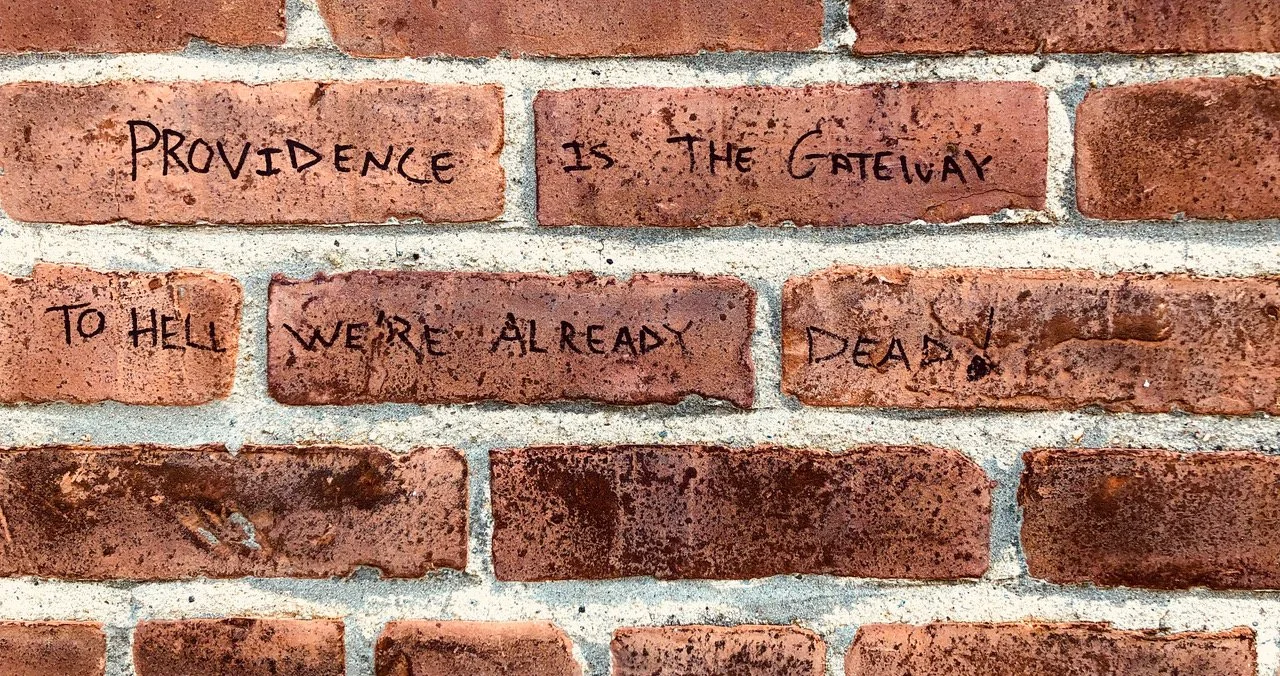

Abandon all hope!

On the wall of the former Rhode Island Board of Elections building on Branch Avenue, Providence

— Photo by William Morgan

Chris Powell: Has abortion really become state’s highest social good? the phony U.S. debt-ceiling crisis

The rear of College Row at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn. From left to right: North College, South College, Memorial Chapel, Patricelli '92 Theater

— Photo by Smartalic34

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Maybe nothing less could have been expected from Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn., a citadel of leftist groupthink, but according to the university chapter of the Democratic Socialists, the university has agreed to pay for abortions for its students. Not for treatment of cancer or multiple sclerosis or Crohn’s disease or AIDS or other serious ailments, just abortions.

The university’s implication is that while those ailments are often fatal, abortion is the highest social good.

Wesleyan’s decision rhymes with the clamor at the state Capitol, where proclamations of fidelity to abortion rights trump the daily shootings in the cities, the repeat offenders running rampant, the collapse of public education, the worsening poverty, and the government’s shift away from public service to a mere pension and benefit society.

The people who extol abortion well may believe that it is the highest social good. Yet their clamor seems a bit out of place in Connecticut, where a Roe v. Wade policy on abortion was enacted years ago and will remain in force whatever other states do with their new freedom to legislate on the issue. In Connecticut, abortion anywhere, any time is challenged only by occasional calls for requiring parental notification for abortion for minors. While parental notification has broad support with the public, nothing can sway the abortion fanatics in control of the General Assembly’s Democratic caucus.

So abortion fanaticism may be meant mainly as a distraction from the defects of both the national and state Democratic administrations. It presumes that clamor about abortion can induce most people to forget about inflation, forever wars, open borders, and the soaring national debt as long as there is a chance that the law somewhere might impede abortion of viable fetuses.

The political judgment of Connecticut’s abortion fanatics may be correct. After all, so much nuttiness in the state now goes without serious challenge -- from transgenderism to unemployment benefits for strikers to reimbursing the abortion expenses of women in abortion-restricting states who come to this state for abortions.

Still, the fanatics might not represent majority opinion or even anything close to it. If their power is mainly their ability to intimidate those who disagree, their position could actually be weak.

Connecticut won’t find out what the public really thinks until some people in public life try talking back -- calmly and rationally but firmly -- daring to attempt argument.

xxx

Hysteria has overtaken the controversy over the limit on the federal government’s debt.

The other day Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned that the refusal by Republicans in Congress to raise the debt ceiling would cause a “constitutional crisis” that might cripple the economy and financial system as the government ran out of money and defaulted on some of its bonds.

Nonsense. Because it retains the power of money creation, the federal government can never run out of money. It can create money to infinity. The government prefers not to create money so frankly, since it might be inflationary, but the government has the power.

And of course the government can raise revenue in a way that won’t aggravate concerns about inflation. It can raise money the old-fashioned way: through taxes.

So why the insistence on more borrowing?

It’s because Congress and President Biden, like his predecessors, enjoy distributing infinite goodies without having to make current taxpayers pay for what they really cost. The burden is to be transferred to future generations -- and to other countries, which the U.S. government pressures to finance this country’s debt, and thus its parasitic lifestyle. The president and Congress believe that Americans have the right to live at the expense of the rest of the world.

Calling again for raising the debt ceiling, Biden says: “America is not a deadbeat nation. We pay our bills.” But we don’t pay our bills, since borrowing to pay debt doesn’t repay debt at all. It just creates more debt.

Taxes repay debt, but apparently a “constitutional crisis” is preferable to more taxes.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

The mysteries of gray/grey

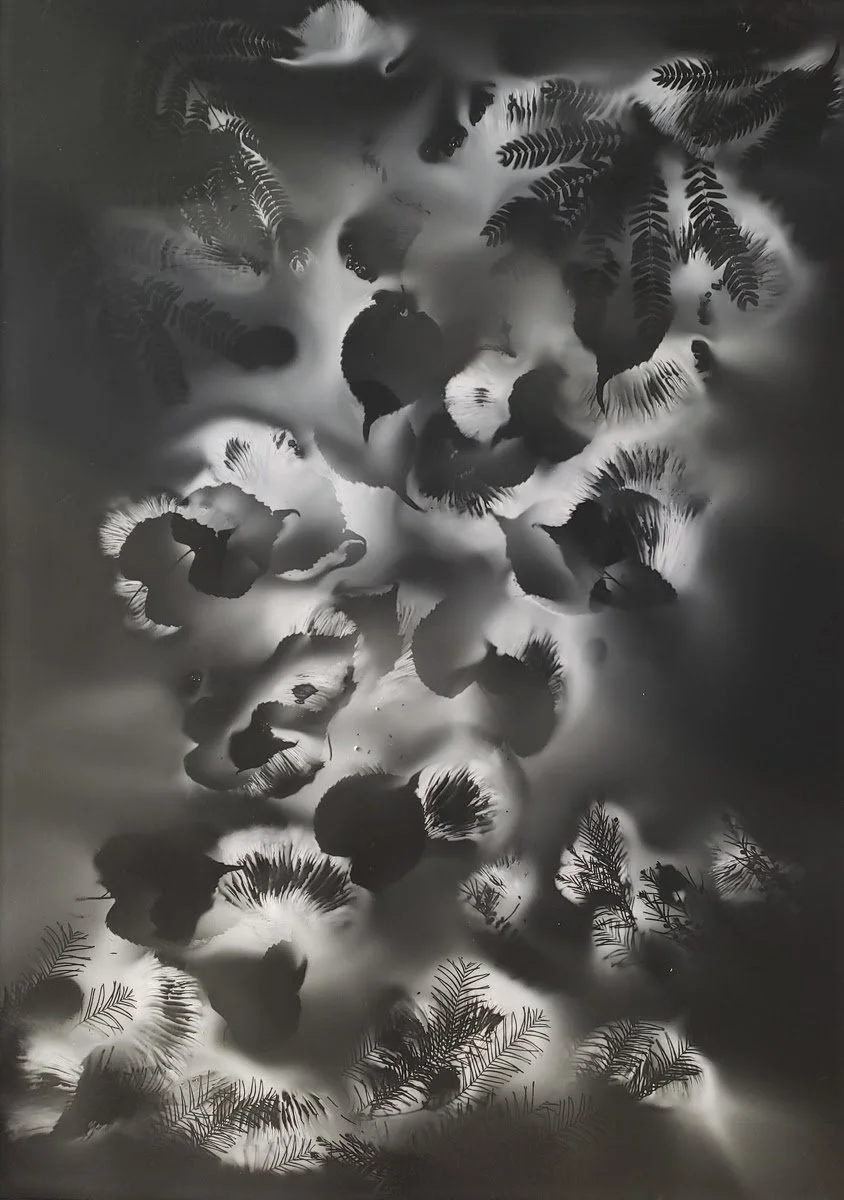

“Upward” (mushroom spores on paper), by western Massachusetts-based artist Madge Evers, in the group show “Grey Areas,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Aug. 2-27

The gallery says:

This year’s annual exhibition by Kingston Gallery’s Associate Artists explores the theme of “Grey Areas’’ from different perspectives and media. …The 10 artists interpret our world with divergent approaches to both the enigmatic concept and the color grey….They explore liminal places, ideas, and eras that generate questions - many without answers. Responding to the existential areas of an unknowable future or the space between ecosystems, they wonder how to acknowledge non-human collaborators, the myriad ‘what-ifs’ of depression, and the question of secrecy and abuses in institutions and systems of government that operate in obscurity. The diversity of work plays with grey’s ability to take on hue and enliven color, consider the spin of the stories we tell, uncertainty in understanding our world, and the difficulty of truly knowing the space one occupies in that world.’’

xxx

“Madge Evers has adapted the spore print, a mushroom identification tool typically used by mycologists and foragers, to create biomorphic monochromatic works on paper. Like the wind and other animals, she spreads the spores of mushrooms; germinates their powdery spores as they land on paper and creates her version of a fruiting body - it forms a two-dimensional image rather than toadstool. In this interdependence with mushrooms, she wonders: How do I best acknowledge my unwitting collaborators?’’

View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Mass., after a thunderstorm—The Oxbow (of the Connecticut River) (1836), by Thomas Cole

Except in February?

The “town’’ in this crime novel with Ben Affleck is the once tough but now substantially gentrified Boston section of Charlestown.

“Boston Street Scene (Boston Common), 1898-1899, by Edward Mitchell Bannister.

“When I grew up, there really was the sense of why would you want to live anywhere else?”

– Ben Affleck (born 1972), American actor and director, raised in Cambridge, Mass.

How to handle communications in an environmental crisis

The North Cape oil spill took place on Jan. 19, 1996, when the oil barge North Cape and the tug Scandia grounded on Moonstone Beach, in South Kingstown, R.I., after the tug caught fire in its engine room during a winter storm. An estimated 828,000 gallons of home-heating oil escaped, causing major pollution.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Christopher Reddy, a veteran scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, has just published a very useful, accessible and sometimes exciting guidebook for those navigating the shoals of environmental crises, about which Dr. Reddy, an expert on the effects of oil spills, among other things, has long personal experience. Science Communication in a Crisis: An Insider’s Guide has an engaging conversational voice and should be read by scientists, especially the more public-facing ones, journalists, communications officials, regulators, politicians and, for that matter, the general public.

Much of the expertise displayed in the book stems from the lessons he learned as a participant in efforts to study and mitigate such disasters as the massive Deepwater Horizon spill, in the Gulf of Mexico, in 2010.

Members of the groups above should keep Dr. Reddy’s book on their desks. And its compact guidebook format makes it easy to take into the next environmental emergency.

Sam Pizzigati: The outrage of child labor is creeping back into the U.S.

"Addie Card, 12 years. Spinner in North Pormal Cotton Mill, Vt." by Lewis Hine, 1912.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Ever since the middle of the 20th century, our history textbooks have applauded the reform movement that put an end to the child-labor horrors that ran widespread throughout the early Industrial Age.

Now those horrors are reappearing.

The number of kids employed in direct violation of existing child labor laws, the Economic Policy Institute reported this year, has soared 283 percent since 2015 — and 37 percent in just the last year alone.

More recently there was the alarming news that three Kentucky-based McDonald’s franchising companies had kids as young as 10 working at 62 stores across Kentucky, Indiana, Maryland, and Ohio. Some children were working as late as 2 a.m.

Federal legislation to crack down on child labor has stalled out amid Republican opposition. And at the state level, lawmakers across the country are moving to weaken — or even eliminate — child labor limits.

One bill in Iowa introduced earlier this year would let kids as young as 14 labor in workplaces ranging from meat coolers to industrial laundries. And Arkansas just eliminated the requirement to “verify the age of children younger than 16 before they can take a job,” the Washington Post reported.

Over a century ago, in the initial push against child labor, no American did more to protect kids than the educator and philosopher Felix Adler. In 1887, Adler sounded the alarm on child labor before a packed house at Manhattan’s famed Chickering Hall.

The “evil of child labor,” Adler warned, “is growing to an alarming extent.” In New York City alone, some 9,000 children as young as eight were working in factories. Many of those kids, Alder said, “could not read or write” and didn’t even know “the state they lived in.”

By the end of 1904, as the founding chair of the National Child Labor Committee, Adler had broadened the battle against exploiting kids. He railed against the “new kind of slavery” that had some 60,000 children under 14 working in Southern textile mills up to 14 hours a day, up from “only 24,000” just five years earlier.

Adler put full responsibility for this exploitation on those he called America’s “money kings,” who he said were after “cheap labor.” Alongside his campaigns to limit child labor, Adler pushed lawmakers to end the incentives that drive employers to exploit kids.

Aiming to prevent the ultra rich from grabbing all the wealth they could, Adler called for a tax rate of 100 percent on all income above the point “when a certain high and abundant sum has been reached, amply sufficient for all the comforts and true refinements of life.”

After the United States entered World War I, the national campaign for a 100-percent top income-tax rate on America’s highest incomes had a remarkable impact. In 1918, Congress raised the nation’s top marginal income tax rate up to 77 percent, 10 times the top rate in place just five years earlier.

During World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt renewed Adler’s call for a 100-percent top tax rate on the nation’s super rich. By the war’s end, lawmakers had okayed a top rate — at 94 percent — nearly that high. By the Eisenhower years, that top rate had leveled off at 91 percent.

Felix Adler died in 1933, before he could see the full scope of his victory. But by the mid-20th Century those inspired by him had won on both his key advocacy fronts. By the 1950s, America’s rich could no longer keep all they could grab, and masses of mere kids no longer had to labor so those rich could profit.

The triumphs thatAdler helped animate have now come undone. We need to recreate them.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

1900 ad for McCormick farm machines

#child labor

‘Fragrant with familiar baum’

On the Appalachian Train in Massachusetts’s Beartown State Forest, in The Berkshires

Blue blazes marking the Metacomet Trail, in Farmington, Conn.

— Photo by Ragesoss

New England woods are fair of face,

And warm with tender, homely grace,

Not vast with tropic mystery,

Nor scant with arctic poverty,

But fragrant with familiar balm,

And happy in a household calm.

And such O land of shining star

Hitched to a cart! thy poets are,

So wonted to the common ways

Of level nights and busy days,

Yet painting hackneyed toll and ease

With glories of the Pleiades.

For Bryant is an aged oak,

Beloved of Time, and sober folk;

And Whittler, a hickory,

The workman's and the children's tree;

And Lowell is a maple decked

With autumn splendor circumspect.

Clear Longfellow's an elm benign,

With fluent grace in every line

And Holmes, the cheerful birch intent;

On frankest, whitest merriment

While Emerson's high councils rise;

A pine, communing with the skies.

— “New England Woods,’’ by Amos Russel Wells (1862-1933), American editor, author and professor. The surnames here are of famous New England poets. #New England Woods

Llewellyn King: Investing in a green future that works

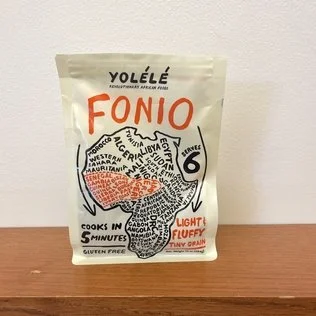

Fonio is an African sustainable “supergrain.’’

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Adam Smith, the great Scottish economist and moral philosopher, didn’t have to confront the environmental crisis, the health-care delivery challenge or any of today’s issues. But his economic theory and moral philosophy — his unseen hand — are as pertinent today as they were in his lifetime.

Notably, Smith believed market forces were a force for good and a force for simply getting things done, acting.

A cardinal virtue of the market at work is discipline. Respect for the bottom line works wonders in producing discipline and results, even in the green economy that places a premium on sustainability.

And it is why Pegasus Capital Advisors, the fast-growing, impact investment firm based in Stamford, Conn., is having so much success in Africa, the Caribbean and South America, and Southeast Asia. In all, Pegasus is exploring investments in more than 40 countries.

An investment by Pegasus, under its ebullient founder, chairman and CEO, Craig Cogut, must make money and meet other strict criteria. It must help — and maybe save — the local environment. It must benefit local people with employment at decent wages. And it must have a long future of social and economic benefit.

And Pegasus always looks for a strong local partner.

In Africa, Cogut told me, the growing of sustainable crops should be wedded to cold storage and processing, which should be local. He has invested in a marketer of fonio, an African “supergrain.”

“Agriculture and fishing are important sources of food in the global south, but they get shipped out and they need to stay local,” Cogut said.

“In Ecuador, we’re focused on sustainable fishing and shrimp farming,” he said, adding, “Shrimp is an amazing source of protein, but you have to do it in an environmentally correct way.”

Cogut has two passions, and they are where he directs investments: the environment, and health and wellness.

A Harvard-trained lawyer, Cogut took his first job with a law firm in Los Angeles. He became an environmentalist while living there and visiting the nearby National Parks frequently. To this day, watching birds while hiking on Audubon Society trails in Connecticut, where he lives, is his passion.

He learned the art of big deals while working with the investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert during its heyday. When it folded, in 1990, Cogut became one of the founding partners of Apollo Advisors, the wildly successful private-equity firm. After leaving Apollo, in 1996, he founded Pegasus, the private-equity firm that is making a difference.

A Pegasus success is Six Senses, which manages eco hotels and resorts with sensitivity to the environment. Pegasus sold Six Senses to IHG in 2019 and is currently partnering with IHG to develop new Six Senses resorts, including an eco-hotel on one of the Galapagos islands.

“We have been working with the Ecuadorian national park system to replicate what was there before Darwin’s time,” Cogut said.

Another previous Pegasus investment has restored a biodiesel plant in Lima, Peru. This plant, which has been sold, provides diesel fuel, produced from food waste and agricultural waste. “It is now helping the Peruvian government reach its environmental goals,” he said.

Off the coast of Nigeria, Cogut was appalled by natural-gas flaring, done in association with oil production. He personally invested in a company to capture the gas and convert it to liquefied natural gas, which is now used to displace diesel in electricity generation — much better for human health and the environment.

After his original investment, a large African infrastructure investor has become the majority owner. This is Cogut’s win-win, where sustainability and commerce come together.

I had a disagreement over how to help Africa’s economy with Britain’s chancellor of the exchequer, Gordon Brown, shortly before he became prime minister. He was trying to raise $50 billion for Africa. I asked Brown how it would be invested so that it would achieve real, positive results. He said, rather unconvincingly, “We’ll give it to the right people.”

If that encounter had taken place today, I would have been able to say, “Call Pegasus. Craig Cogut is the man who can help you.”

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

InsideSources

Stamford , above, has miles of accessible shoreline for recreation and much parkland.

— Photo by John9474 #Pegasus Capitol Advisors

#sustainable agriculture