Run by ‘Patton in pumps’

The latter version, since closed, of Upstairs at the Pudding

“But worse, it was a new apartment. We both knew that, in New England, old was better. Old was cozy; old, like our farmhouse, like the Pudding, had magic and charm.”

― Charlotte Silver in her memoir Charlotte Au Chocolat: Memories of a Restaurant Girlhood

Amazon describes the book:

“Like Eloise growing up in the Plaza Hotel, Charlotte Silver grew up in her mother's restaurant. Located in Harvard Square, Upstairs at the Pudding {in reference to the original version or the restaurant being in the former Hasty Pudding Theatricals building before being moved nearby} was a confection of pink linen tablecloths and twinkling chandeliers, a decadent backdrop for childhood. Over dinners of foie gras and Dover sole, always served with a Shirley Temple, Charlotte kept company with a rotating cast of eccentric staff members. After dinner, in her frilly party dress, she often caught a nap under the bar until closing time. Her one constant was her glamorous, indomitable mother, nicknamed ‘Patton in Pumps,’ a wasp-waisted woman in cocktail dress and stilettos who shouldered the burden of raising a family and running a kitchen. Charlotte's unconventional upbringing takes its toll, and as she grows up she wishes her increasingly busy mother were more of a presence in her life. But when the restaurant-forever teetering on the brink of financial collapse-looks as if it may finally be closing, Charlotte comes to realize the sacrifices her mother has made to keep the family and restaurant afloat and gains a new appreciation of the world her mother has built.’’

Former location of the Hasty Pudding Club at 12 Holyoke Street, Cambridge, now owned by Harvard University but still used by Hasty Pudding Theatricals.

Even without AI….

“Camera Obscura: The Brooklyn Bridge in Bedroom,” by Boston-based artist Abelardo Morell, in the show “Seeing Is Not Believing: Ambiguity in Photography,’’ now at the Currier Museum of Art, in Manchester, N.H.

The gallery says:

“This exhibition explores photographs that make us question what we are looking at. Still lifes, abstract images, and manipulated photographs heighten our sense of wonder. Can we ever trust what we see in a photograph?’’

Except in March

Vermontasaurus sculpture in Post Mills, Vt., in 2010

— Photo by HopsonRoad

‘‘Vermont, Designed by the Creator for the Playground of Continent.’’

— The Green Mountain State’s first state-sponsored tourist brochure (1911)

#Vermont

Vermont will sue

“White Mountains” (digital), by Hooksett, N.H.-based artist Nate Twombly, at the Rochester (N.H.) Museum of Fine Arts.

That time again

Rhodora

In May, when sea-winds pierced our solitudes,

I found the fresh Rhodora in the woods,

Spreading its leafless blooms in a damp nook,

To please the desert and the sluggish brook.

The purple petals fallen in the pool

Made the black water with their beauty gay;

Here might the red-bird come his plumes to cool,

And court the flower that cheapens his array.

Rhodora! if the sages ask thee why

This charm is wasted on the earth and sky,

Tell them, dear, that, if eyes were made for seeing,

Then beauty is its own excuse for Being;

Why thou wert there, O rival of the rose!

I never thought to ask; I never knew;

But in my simple ignorance suppose

The self-same power that brought me there, brought you

— “The Rhodora,’’ by Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), New England-based essayist and philosopher

Don Pesci: Conn.’s neo-progressives move to take down fiscal guard rails

VERNON, Conn.

A Hearst editorial has been answered by Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont.

“The Hearst Connecticut editorial, ‘Caution on the budget can go too far,” the governor wrote, “suggests that our balanced budgets and budget surpluses are shortchanging spending on important needs. Respectfully, I disagree.

“On the contrary, the fiscal guard rails established by the legislature in 2017, and recently reconfirmed on a bipartisan basis for another five to 10 years, have served as the foundation for our state’s fiscal turnaround, stability and economic growth. Higher growth is more than GDP — it means more families moving into the state, more new businesses, more job opportunities and more tax revenue (not more taxes, but more taxpayers). All of which have allowed us to increase investments in core services while proposing the biggest middle-class tax cut in our history.”

Neo-progressives in the General Assembly appear to be moving towards dismantling by degrees the spending guard rails supported by Lamont and a majority of Republicans in the General Assembly, now that Democrats have achieved a near veto-proof majority in the state legislature. Connecticut’s taxpayers and reporters may recall that the guard rails – essentially limits on spending – were installed after Republicans had achieved numerical parity in the state House. That parity, and with it an opportunity to press responsible budgetary restraints on profligate spenders, has long since gone by the wayside. The neo-progressive mutineers who invariably favor unlimited spending are now in charge of the General Assembly.

Why don’t we just spend the state’s mouthwatering surplus on necessary expenditures, the Hearst editorial asks?

“The surplus,” Lamont answers, “is invaluable in a state with some of the biggest debt per capita in the country, with the costs of carrying that debt eating into the resources we need to maintain and expand key services. But what the editorial fails to articulate is the volatility associated with the surplus. What is ‘here today’ can just as easily be ‘gone tomorrow,’ as they say.”

The governor is a bit too polite to put the matter more boldly. In fact, surpluses have in the past disappeared in the blink of an eye because they have been used by vote thirsty Democrats in the General Assembly to permanently increase long term spending. That is to say: Past surpluses have been folded into future increases in spending in budgets affirmed by neo-progressive Democrats who believe that if spending is a good thing, more spending is always better. It is this ruinous idea that has swollen all past budgets. The last annual pre-Lowell Weicker income tax budget was $8.5 billion. The current biannual budget is $51 billion, a more than fourfold increase in spending.

“The problem with socialism” – i.e., unrestrained, autocratic spending – Margaret Thatcher reminded us, “is that, sooner or later, you run out of other people’s money.” There are some indications that voters in Connecticut are running out of patience with heedless neo-progressive legislators who cavalierly run out of other people’s money.

The single line in Lamont’s challenging answer to the initial Hearst editorial that drives neo-progressives batty is this one: ‘Funding future programs via a current surplus is irresponsible” and, Lamont might have added, costly in the long run to a state that hopes to liquidate part of its gargantuan debt of some $68 billion by poaching businesses from more predatory Eastern Seaboard states and increasing business productivity in Connecticut.

By trimming Lamont’s tax cuts and agitating for increases in spending, neo-progressives in the General Assembly are sending a message to the governor that the dominant left in the state has no intention of seriously cutting net-spending. The easiest way to corner a vote in Connecticut is to use surplus money to buy votes, and the purchasing of votes cannot be done in the absence of budget surpluses, either real or imaginary.

“Getting and spending, we know, are conjoined twins. Years after [former Governor Lowell] Weicker had left politics,” this writer noted four years ago, “he appeared with a panel of businessmen at the Hartford Club. Asked to reflect on Connecticut’s then burgeoning debt, Weicker groaned, “Where did it all go?” But he knew where it went. Politicians spent it and, by raising taxes, relieved themselves of cutting governmental costs, always a painful ordeal for those who have pledged their political troth to state employee unions, Connecticut’s fourth branch of government.”

The neo-progressive wing of Connecticut’s Democrat Party simply waited Weicker out. It is infinitely patient.

Don Pesci is Vernon-based columnist.

The Tower on Fox Hill, in Vernon

From storm to sun and back

In the Boston Public Garden in May

“The spring in Boston is like being in love: bad days slip in among the good ones, and the whole world is at a standstill, then the sun shines, the tears dry up, and we forget that yesterday was stormy.”

—Louise Closser Hale (1872-1933) actress, playwright and novelist

#Boston

Art about museums

“NY Times Museum Section with Cy Twombly” (mixed media wall sculpture), by Paul Rousso, in group show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through June 9.

#Paul Rousso

Llewellyn King: How will we know what’s real? Artificial intelligence pulls us into a scary future

Depiction of a homunculus (an artificial man created with alchemy) from the play Faust, by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832)

Feature detection (pictured: edge detection) helps AI compose informative abstract structures out of raw data.

— Graphic by JonMcLoone

#artificial intelligence

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A whole new thing to worry about has just arrived. It joins a list of existential concerns for the future, along with global warming, the wobbling of democracy, the relationship with China, the national debt, the supply-chain crisis and the wreckage in the schools.

For several weeks artificial intelligence, known as AI, has had pride of place on the worry list. Its arrival was trumpeted for a long time, including by the government and by techies across the board. But it took ChatGPT, an AI chatbot developed by OpenAI, for the hair on the back of the national neck to rise.

Now we know that the race into the unknown is speeding up. The tech biggies, such as Google and Facebook, are trying to catch the lead claimed by Microsoft.

They are rushing headlong into a science that the experts say they only partly understand. They really don’t know how these complex systems work; maybe like a book that the author is unable to read after having written it.

Incalculable acres of newsprint and untold decibels of broadcasting have been raising the alarm ever since a ChatGPT test told a New York Times reporter that it was in love with him, and he should leave his wife. Guffaws all round, but also fear and doubt about the future. Will this Frankenstein creature turn on us? Maybe it loves just one person, hates the rest of us, and plans to do something about it.

In an interview on the PBS television program White House Chronicle, John Savage, An Wang professor emeritus of computer science at Brown University, in Providence, told me that there was a danger of over-reliance, and hence mistakes, on decisions made using AI. For example, he said, some Stanford students partly covered a stop sign with black and white pieces of tape. AI misread the sign as signaling it was okay to travel 45 miles an hour. Similarly, Savage said that the smallest calibration error in a medical operation using artificial intelligence could result in a fatality.

Savage believes that AI needs to be regulated and that any information generated by AI needs verification. As a journalist, it is the latter that alarms.

Already, AI is writing fake music almost undetectably. There is a real possibility that it can write legal briefs. So why not usurp journalism for ulterior purposes, as well as putting stiffs like me out of work?

AI images can already be made to speak and look like the humans they are aping. How will you recognize a “deep fake” from the real thing? Probably, you won’t.

Currently, we are struggling with what is fact and where is the truth. There is so much disinformation, so speedily dispersed that some journalists are in a state of shell shock, particularly in Eastern Europe, where legitimate writers and broadcasters are assaulted daily with disinformation from Russia. “How can we tell what is true?” a reporter in Vilnius, Lithuania, asked me during an Association of European Journalists’ meeting as the Russian disinformation campaign was revving up before the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Well, that is going to get a lot harder. “You need to know the provenance of information and images before they are published,” Brown University’s Savage said.

But how? In a newsroom on deadline, we have to trust the information we have. One wonders to what extent malicious users of the new technology will infiltrate research materials or, later, the content of encyclopedias. Or are the tools of verification themselves trustworthy?

Obviously, there are going to be upsides to thinking-machines scouring the internet for information on which to make decisions. I think of handling nuclear waste; disarming old weapons; simulating the battlefield, incorporating historical knowledge; and seeking out new products and materials. Medical research will accelerate, one assumes.

However, privacy may be a thing of the past — almost certainly will be.

Just consider that attractive person you just saw at the supermarket, but were unsure what would happen if you struck up a conversation. Snap a picture on your camera and in no time, AI will tell you who the stranger is, whether the person might want to know you and, if that should be your interest, whether the person is married, in a relationship or just waiting to meet someone like you. Or whether the person is a spy for a hostile government.

AI might save us from ourselves. But we should ask how badly we need saving — and be prepared to ignore the answer. Damn it, we are human.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Foot by foot

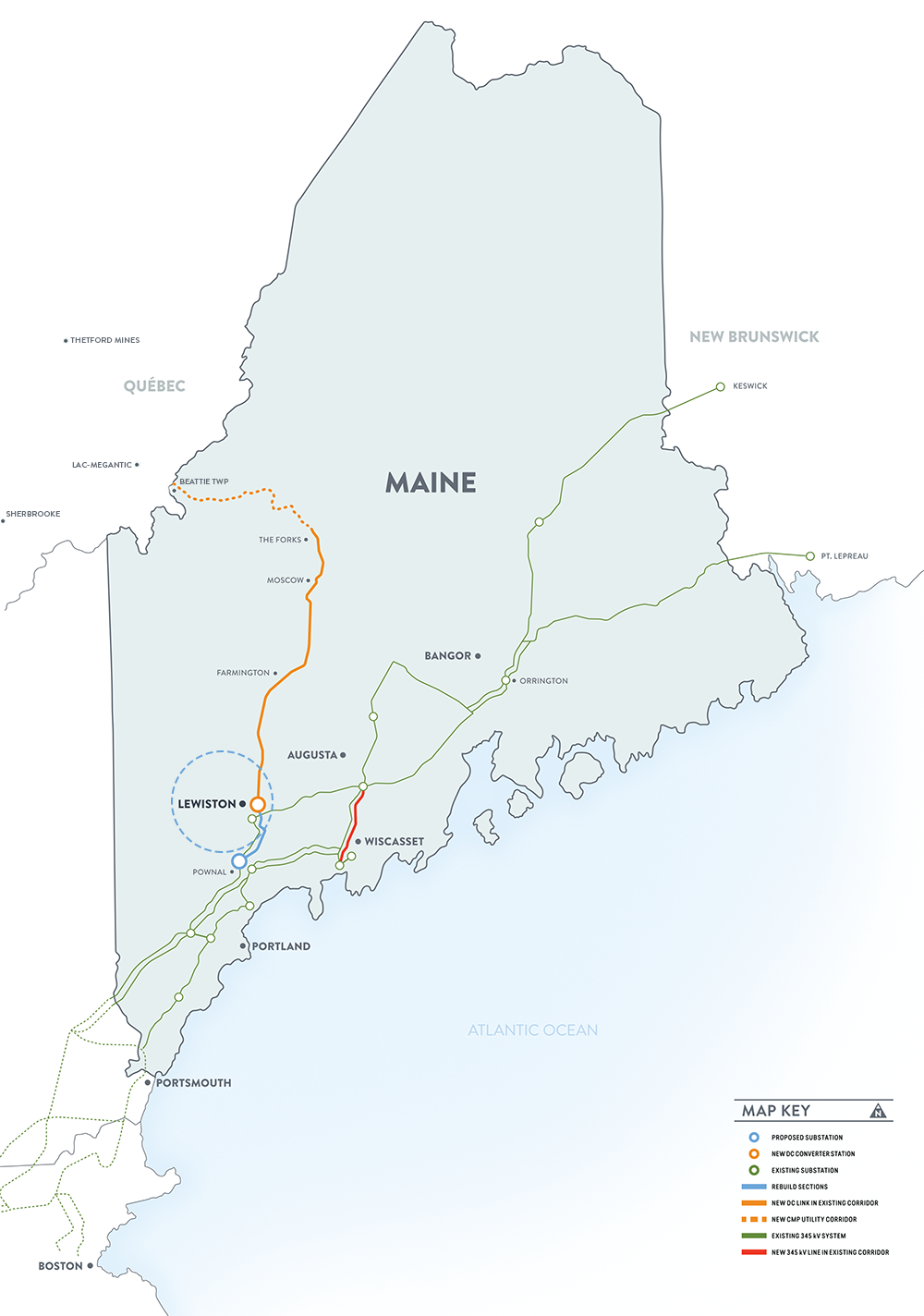

New England Clean Energy Connect map

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s recently been progress, albeit still too slow, on making New England’s energy greener.

First, there’s that a state jury in Maine has voted 9-0 to let proceed the long-delayed transmission line for moving electricity from Hydro Quebec into our region. In a deeply dubious move, foes of the line, including three companies with natural-gas facilities in the state, had sought to kill the Avangrid Inc. project, called New England Clean Energy Connect. They did this by putting up a ballot question approved by voters after a massive campaign against the project that was aimed at retroactively killing Avangrid’s project, which regulators had approved. Armed with permits, the company had already spent hundreds of millions of dollars before the ballot question to clear the wooded, mostly wilderness route, logically assuming that it could legally do so. Talk about unfair

The jury verdict came in the wake of a Maine Supreme Judicial Court ruling that in effect backed the continuation of the project.

It seems that as of this writing that the project will be completed, adding more clean juice to the region’s grid to such other new green-energy production as also-too-long-delayed offshore wind projects and solar. (Will nuclear fusion to generate electricity eventually be our savior? Research on it, much of it happening in New England, is coming along at a good clip.)

Utility Dive reported:

Anne George, spokesperson for ISO New England (which manages the region’s grid), said that it’s pleased that the project can move forward.

“The New England states’ ambitious climate goals will require building significant amounts of new infrastructure in a region where building infrastructure has been difficult,’’ she said.

Phelps Turner, a senior lawyer at the Conservation Law Foundation, said the delay caused by the legal challenge is “symptomatic of building energy infrastructure in New England.”

“We lost a lot of time.’’

New England, despite many of its citizens’ progressive rhetoric, is a remarkably Nimby place, in energy matters, housing and some other fields. Many Red States have done far more than New England in setting up renewable-energy operations.

Then there are such little noted options as geothermal. Consider National Grid’s pilot program at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell. The company will use boreholes to see if a geothermal network can be established there using piping and pumps to pull heat out of the ground to warm the university’s buildings in cold weather and then pump heat from them into the ground to cool them in the summer.

#New England Clean Energy Connect

‘Restlessness and vulnerability’

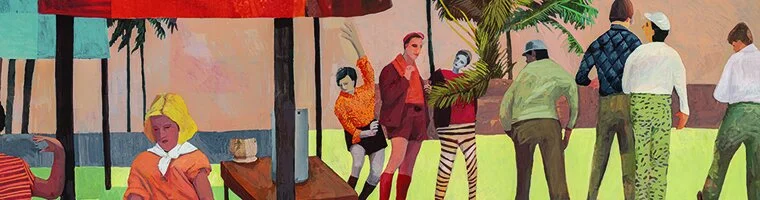

From Hannah Morris’s show, “Moveable Objects,’’ at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum and Art Center, through April 30, 2024

Ms. Morris, who lives in Barre, Vt., writes:

“These recent works are a continued exploration of the contrast between ambiguity and specificity. The space between the two creates a stage for new visual narratives. Applying layers of paint over an initial collage, I cover, expose, and refashion to tell new stories. I use found imagery to ground myself in a moment in time, and from there, I develop a new narrative by combining old imagery with new. Using a visual language based on colors, tones, marks, and details, I create believable yet implausible scenes. The underlying restlessness and vulnerability of the people in these scenes is a reflection of a struggle to define ourselves.’’

# Hannah Morris #Barre# Brattleboro

Barre’s U.S. Post Office is one of many Barre buildings and sculptures made from stone from the famous local granite quarries.

Barre's Hope Cemetery is widely known for its elaborate granite headstones.

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Thinking of heaven and earth

Spring clouds over Temple Emanu-El on the East Side of Providence

— Photos by Lydia Whitcomb

A downtown homeless person classically draped

— Photo and text by William Morgan

It’s 11 on a Saturday morning in downtown Providence, and someone is sleeping in. This stretch of Chapel Street between Grace Church and the Providence Performing Arts Center has two or three encampments, where building-entrance alcoves provide a modicum of shelter from the elements.

The sadness and embarrassment of homeless people, and the failure of a supposedly enlightened city to take care of its marginalized and less fortunate, tear at one’s heartstrings.

Whatever the issues around social conscience and civic breakdown, some credit is due to this intrepid street denizen. He or she is wrapped in an ecclesiastical purple blanket, like a giant burqa without eye holes. The draping of the fabric recalls classical Greek statuary, such as the Elgin Marbles, from The Parthenon.

As I passed, from a tent pitched in the next entryway, a female voice wafted out, “Have a nice day.’’

William Morgan is an architecture writer and historian based in Providence. His latest book, Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, will be published in October.

New innovation-focused BalanceBlue Lab at the New England Aquarium

A weedy sea dragon in the New England Aquarium’s Temperate {Zone} Gallery

Edited from a New England Council report

The New England Aquarium, on Boston’s waterfront, has announced creation of the BalanceBlue Lab, which will support innovation in such sectors as fishing, aquaculture, offshore wind and coastal resiliency.

Emiley Zalesky Lockhart will be the inaugural head of the BalanceBlue Lab, with the title of associate vice president for ocean sustainability, technology and innovation for the aquarium. Before joining the aquarium, Lockhart was deputy general counsel and secretary of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and a general counsel and policy director in the Massachusetts Senate. Her main goals regarding innovation from this new lab are to support startups and industry technical advising.

“I think the idea is leveraging that science and being technical experts and helping companies, whether startups or large organizations, figure out how to create solutions in a more sustainable and responsible manner,” said Zalesky.

Outside the aquarium on a summer day

Grandeur or at least mystery at Good Fortune

— Photo and text by William Morgan

At a time when most public art is too realistic, too political, and just too awful, it can be a pleasure to stumble upon some unplanned artistic achievement– art in spite of itself.

This urinal in Good Fortune, the giant warehouse of Asian food in the Elmwood section of Providence, offers humor, dignity, and an appropriate aura of mystery befitting an intriguing work of art.

This plumbing fixture is broken, but the sign, “Operation Suspended,’’ hints at grander exploits, such as the cancellation of a moon shot or an aborted Navy Seals raid.

Set off by faux marble and black poly-something-or-other, the flushing mechanism takes on the look of a sleek, abstract chromium sculpture – a tribute to American industrialization, perhaps. A dismembered torso, or perhaps a tuxedo on a coat hanger, lurks beneath the shiny, elegant, mink-coat-black drape.

High fashion or a postponed plumbing repair?

William Morgan is a Providence-based writer and architectural historian. He holds a Ph.D. in American Art from the Bidens’ alma mater, the University of Delaware. His latest book, Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, will be published this fall.

#art #Providence

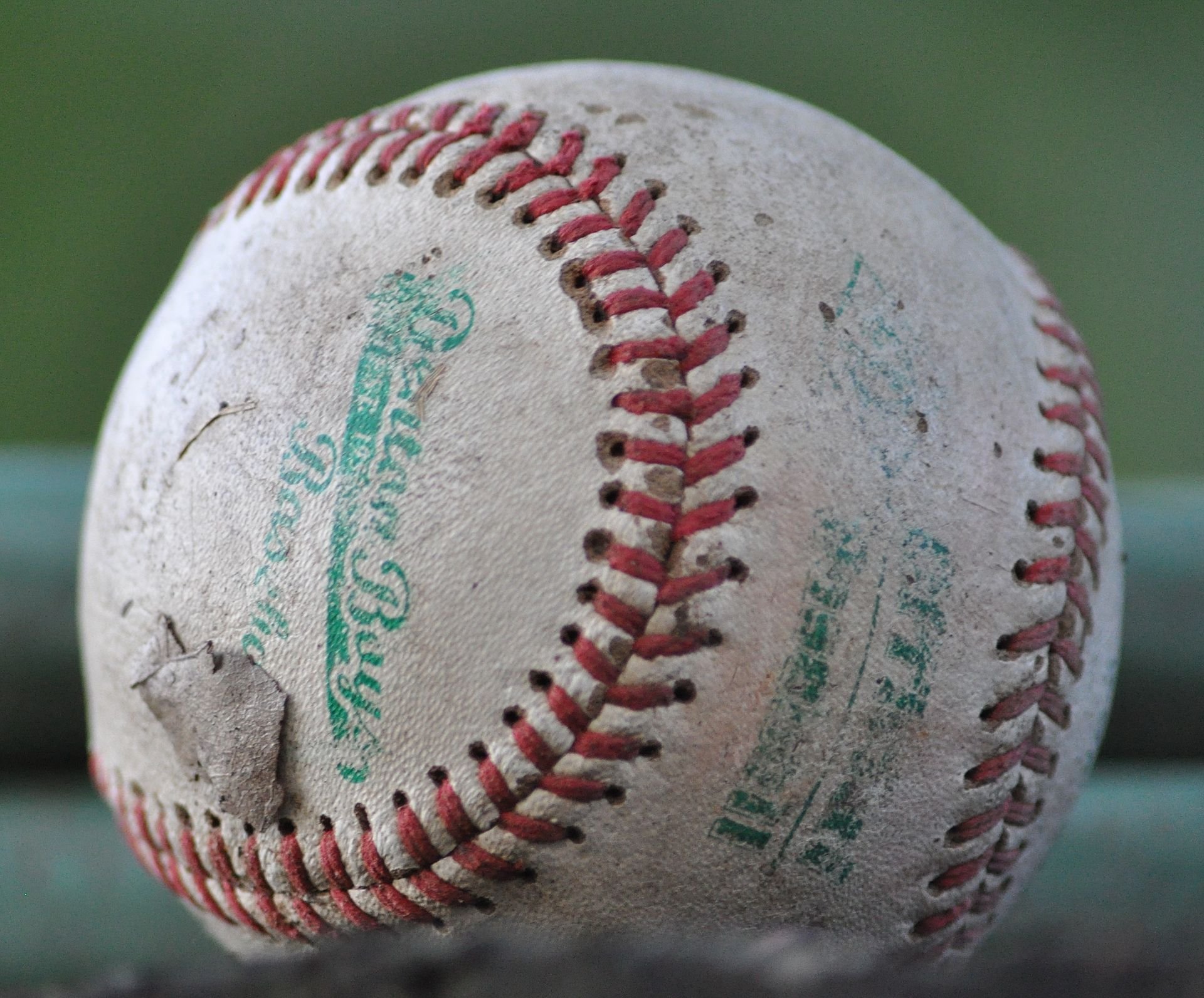

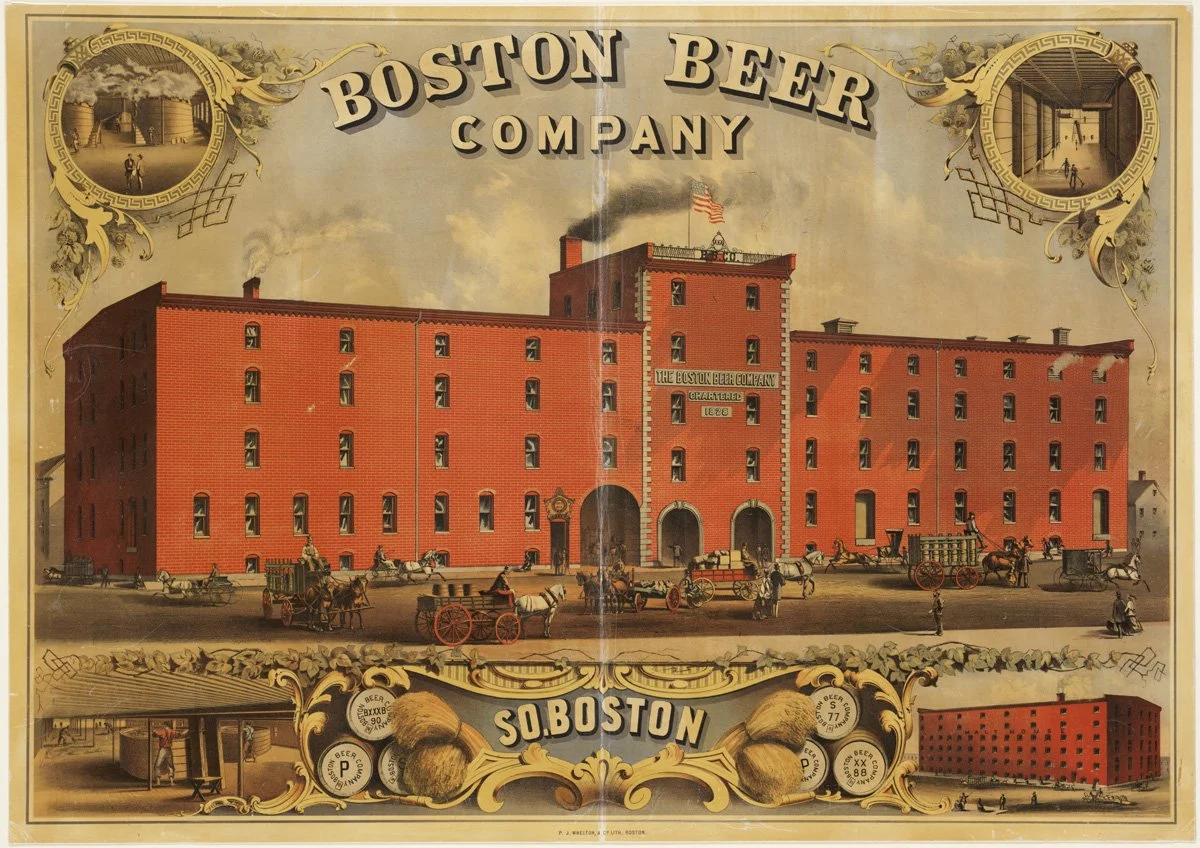

Sam Pizzigati: Major League Baseball’s dangerous new beer-selling extension

— Photo by Schyler

The original Boston Beer Company about 1880. The current version of the company, founded in 1984, makes Samuel Adams Beer, which is very popular at Fenway Park.

From OtherWords.org

BOSTON

“Take me out to the ball game,” as baseball’s fabled 1908 classic song puts it. The ancient refrain ends: “I don’t care if I never get back.”

Unfortunately, America’s billionaire baseball owners may not care if you get back, either. Just look at how baseball’s owners are reacting to the success of Major League Baseball’s new rules to speed up the game.

“Time of play” has emerged over recent years as a major concern of just about everybody in baseball, especially fans.

Decades ago, the vast majority of Major League games ended in less than three hours. In 1981, for instance, the average game ran just a tad over two-and-a-half. By 2021, average games were running over 40 minutes longer.

Those long times were bumming out fans — and baseball owners as well. These owners worried that fans would simply stop showing up if the games kept lasting so long. The answer? A set of mostly welcome rule changes that speed up the games.

These rule changes went into effect this season. With no runners on base, pitchers must now deliver their pitches within 15 seconds. A new “pitch clock” is even keeping track.

Fans seem to love the pitch clock and other new time-saving rules. Games are already running significantly shorter, by just over a half-hour. Players like the new pace of play, too.

But the owners now realize that they have a problem. With shorter game times, fans have less time to buy beer. Owners don’t like that. They make a lot of money off beer sales — the average beer at a Major League ballpark last year cost nearly $7, with fans in Chicago paying well over $10.

How are owners reacting to this spring’s drooping beer sales? Not well. To maintain the beer revenue they net, some owners have actually started putting baseball fans at serious risk.

Up until this year, most ballparks stopped selling beer in the seventh inning of their nine-inning games. That policy made eminent sense. No one should be drinking beer one moment, then heading out to the parking lot and the drive home the next.

Baseball owners, facing shorter games, are now starting to change that long-standing policy. Several Major League ball clubs have begun extending beer sales through the eighth inning.

To be responsible, Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Matt Stram counters, baseball’s beer policies ought to be going in the exact opposite direction. With games over sooner, ballparks ought to be cutting beer sales off before the seventh inning.

The seventh-inning cut-off, Stram points out, gives “our fans time to sober up and drive home safe.” With innings and games now taking less time, he asks, shouldn’t baseball be moving “beer sales back to the sixth inning” to give fans that same time to sober up?

Baseball’s owners can certainly afford to put safety first. Of baseball’s 30 principal owners, all but six currently rate as billionaires. The “poorest” among the 30, Cincinnati’s Robert Castellini, has a fortune worth $400 million.

Unfortunately, umpires don’t have the authority to call the sport’s owners out. But city councils and other government bodies that have subsidized baseball owners over the years do have some power here.

Local leaders have often used “eminent domain” to seize — in the “public interest” — the property that sports owners have wanted for new ballparks and stadiums. Maybe we ought to be using eminent domain to seize sports teams and run them in the public interest.

Boston-based Sam Pizzigati co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

#drinking

#Major League Baseball

#beer

Land conservation has favored the white and wealthy

In Westport, Mass., where affluent summer and year-round homeowners have helped protect much countryside from development.

From article in ecoRI News (ecori.org) by Frank Carini

Concern about environmental and social injustices is spreading, but little research documents how the benefits of land conservation are distributed among different groups of people. In fact, the findings of a new study reveal efforts are likely needed to account for human inequities while continuing land conservation needed for ecological reasons.

Protecting open space from development increases the value of surrounding homes, but a disproportionate amount of that newly generated wealth goes to high-income white households, according to the study published recently in the Proceedings for the National Academy of Sciences.

Land conservation projects do more than preserve open space, ecosystems, and wildlife habitat. These preservation projects can also boost property values for nearby homeowners, and those financial benefits are unequally distributed among demographic groups in the United States.

The study, by researchers from the University of Rhode Island and University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, found that new housing wealth associated with land conservation goes disproportionately to people who are wealthy and white.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

#land conservation

Judith Martin: How to maintain a social network as you age

Except for the cigarettes, healthy social interactions

— Photo by Tup Wanders

See New England Centenarian Study

“It’ s never too late to develop meaningful relationships.’’

— Robert Waldinger, M.D., a clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development.

For years, Carole Leskin, 78, enjoyed a close camaraderie with five women in Moorestown, N.J., a group that took classes together, gathered for lunch several times a week, celebrated holidays with one another, and socialized frequently at their local synagogue.

Leskin was different from the other women — unmarried, living alone, several years younger — but they welcomed her warmly, and she basked in the feeling of belonging. Although she met people easily, Leskin had always been something of a loner and her intense involvement with this group was something new.

Then, just before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, it was over. Within two years, Marlene died of cancer. Lena had a fatal heart attack. Elaine succumbed to injuries after a car accident. Margie died of sepsis after an infection. Ruth passed away after an illness.

Leskin was on her own again, without anyone to commiserate or share her worries with as pandemic restrictions went into effect and waves of fear swept through her community. “The loss, the isolation; it was horrible,” she told me.

What can older adults who have lost their closest friends and family members do as they contemplate the future without them? If, as research has found, good relationships are essential to health and well-being in later life, what happens when connections forged over the years end?

It would be foolish to suggest these relationships can easily be replaced: They can’t. There’s no substitute for people who’ve known you a long time, who understand you deeply, who’ve been there for you reliably in times of need, and who give you a sense of being anchored in the world.

Still, opportunities to create bonds with other people exist, and “it’s never too late to develop meaningful relationships,” said Robert Waldinger, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development.

That study, now in its 85th year, has shown that people with strong connections to family, friends and their communities are “happier, physically healthier, and live longer than people who are less well connected,” according to The Good Life: Lessons From the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness, a new book describing its findings, co-written by Waldinger and Marc Schulz, the Harvard study’s associate director.

Waldinger’s message of hope involves recognizing that relationships aren’t only about emotional closeness, though that’s important. They’re also a source of social support, practical help, valuable information and ongoing engagement with the world around us. And all these benefits remain possible, even when cherished family and friends pass on.

Say you’ve joined a gym and you enjoy the back-and-forth chatter among people you’ve met there. “That can be nourishing and stimulating,” Waldinger said. Or, say, a woman from your neighborhood has volunteered to give you rides to the doctor. “Maybe you don’t know each other well or confide in each other, but that person is providing practical help you really need,” he said.

Even casual contacts — the person you chat with in the coffee shop or a cashier you see regularly at the local supermarket — “can give us a significant hit of well-being,” Waldinger said. Sometimes, the friend of a friend is the person who points you to an important resource in your community you wouldn’t otherwise know about.

Carole Leskin lost a group of close friends just before the pandemic. Though she’s made several new friends online at a travel site, she misses the warmth of being with other people.

After losing her group of friends, Leskin suffered several health setbacks — a mild stroke, heart failure and, recently, a nonmalignant brain tumor — that left her unable to leave the house most of the time. About 4.2 million people 70 and older are similarly “homebound” — a figure that has risen dramatically in recent years, according to a study released in December 2021.

Determined to escape what she called “solitary confinement,” Leskin devoted time to writing a blog about aging and reaching out to readers who got in touch with her. She joined a virtual travel site, Heygo, and began taking tours around the world. On that site, she found a community of people with common interests, including five (two in Australia, one in Ecuador, one in Amsterdam, and one in New York City) who’ve become treasured friends.

“Between [Facebook] Messenger and email, we write like old-fashioned pen pals, talking about the places we’ve visited,” she told me. “It has been lifesaving.”

Still, Leskin can’t call on these long-distance virtual friends to come over if she needs help, to share a meal, or to provide the warmth of a physical presence. “I miss that terribly,” she said.

Research confirms that virtual connections yield mixed results. On one hand, older adults who routinely connect with other people via cellphones and computers are less likely to be socially isolated than those who don’t, several studies suggest. Shifting activities for older adults such as exercise classes, social hours, and writing groups online has helped many people remain engaged while staying safe during the pandemic, noted Kasley Killam, executive director of Social Health Labs, an organization focused on reducing loneliness and fostering social connections.

But when face-to-face contact with other people diminishes significantly — or disappears altogether, as was true for millions of older adults in the past three years — seniors are more likely to be lonely and depressed, other studies have found.

“If you’re in the same physical location as a friend or family member, you don’t have to be talking all the time: You can just sit together and feel comfortable. These low-pressure social interactions can mean a lot to older adults and that can’t be replicated in a virtual environment,” said Ashwin Kotwal, an assistant professor of medicine in the division of geriatrics at the University of California-San Francisco who has studied the effects of engaging with people virtually.

Meanwhile, millions of seniors — disproportionately those who are low-income, represent racial and ethnic minorities, or are older than 80 — can’t afford computers or broadband access or aren’t comfortable using anything but the phone to reach out to others.

Liz Blunt, 76, of Arlington, Texas, is among them. She hasn’t recovered from her husband’s death in September 2021 from non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a blood cancer. Several years earlier, Blunt’s closest friend, Janet, died suddenly on a cruise to Southeast Asia, and two other close friends, Vicky and Susan, moved to other parts of the country.

“I have no one,” said Blunt, who doesn’t have a cellphone and admitted to being “technologically unsavvy.”

When we first spoke in mid-March, Blunt had seen only one person she knows fairly well in the past 4½ months. Because she has several serious health issues, she has been extremely cautious about catching covid and hardly goes out. “I’m not sure where to turn to make friends,” she said. “I’m not going to go somewhere and take my mask off.”

But Blunt hadn’t given up altogether. In 2016, she’d started a local group for “elder orphans” (people without spouses or children to depend on). Though it sputtered out during the pandemic, Blunt thought she might reconnect with some of those people, and she sent out an email inviting them to lunch.

On March 25, eight women met outside at a restaurant and talked for 2½ hours. “They want to get together again,” Blunt told me when I called again, with a note of eagerness in her voice. “Looking in the mirror, I can see the relief in my face. There are people who care about me and are concerned about me. We’re all in the same situation of being alone at this stage of life — and we can help each other.”

Judith Martin is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

#elderly

'I explore my secrets'

“Yearnings (4 men),’’ by Putney, Vt.-based sculptor Susan Wilson, at the Southern Vermont Arts Center, in Manchester, through May 7

She says in her artist statement:

“My work in clay has always been about seeking to understand my place in the world. With clay I explore my secrets, dreams, fears, hopes, and my questions. Using animal and figural images, I tell stories about being together and alone, about yearning for both connection and solitude, about dreaming and waiting, and about hoping for community.

“The three-dimensionality of clay enables me to create real spaces within and outside of which I can tell these stories. These stories float between and around the figures, charging the spaces with energy and unresolved tension.

“My most recent figurative work emerges from my retirement and move to a small and vibrant town {Putney} in Vermont and to a state full of energized people working together to build caring communities. I continue the yearnings for human connections and for a vibrant community as an antidote for all the pain and alienation in the present world. My work continues to be about waiting, hoping, yearning to find that community. I am making archetypal figures with slabs of clay. I am making hollow forms that continue to imply tangible interior space where the mystery and unanswered questions reside. I am exploring polarities such as interior and exterior, solitude and community. I use juxtapositions of scale to enliven and energize my forms and to invite questions.’’

Putney General Store, built 1840–1900

— Photo by Beyond My Ken

Putney is on the west side of the Connecticut River, above the mouth of Sacketts Brook. A falls on the brook provided water power for small early mills, and it was there that the main village was formed in the late 18th Century. But because the town did not have abundant sources of water power, it was largely bypassed by the Industrial Revolution of the mid-19th Century, and remained largely rural. Putney has numerous buildings in the Federal and Greek Revival styles popular during its most significant period of growth, the late 18th to mid-19th Century.

The Theophilus Crawford House, built about 1808 and considered an important example of the Federal style.

‘Hairy with violets’

“I am fleshed at smaller sports, and grow in time

into the mineral thick fell of earth; Vermont

hairy with violets, roses, lilies and like

minions and darlings of the spring, meantime

working wonders, rousing astonishments….”

—From “West Topsham,’’ by John Engels (1931-2007), a Vermont-based poet and teacher. West Topsham is a village in the town of Topsham, Vt.

Town hall in Topsham